64-year-old male, cattle breeder in Extremadura. No relevant medical-surgical history, nor usual treatment. Trip to Senegal 6 years ago. He presents with a 1.5cm diameter skin lesion at the base of the second finger of the right hand, one month old (Fig. 1). He describes the insidious evolution of an erythematous and discretely pruritic punctate papule, which has grown in diameter and volume and now has developed a nodule with granulation tissue, with few symptoms, and without other loco-regional alterations or systemic symptoms. He does not refer to local traumatisms or insect bites. Two weeks before the symptoms started he had been repeatedly milking a cow with mastitis to ensure that the calf was well fed.

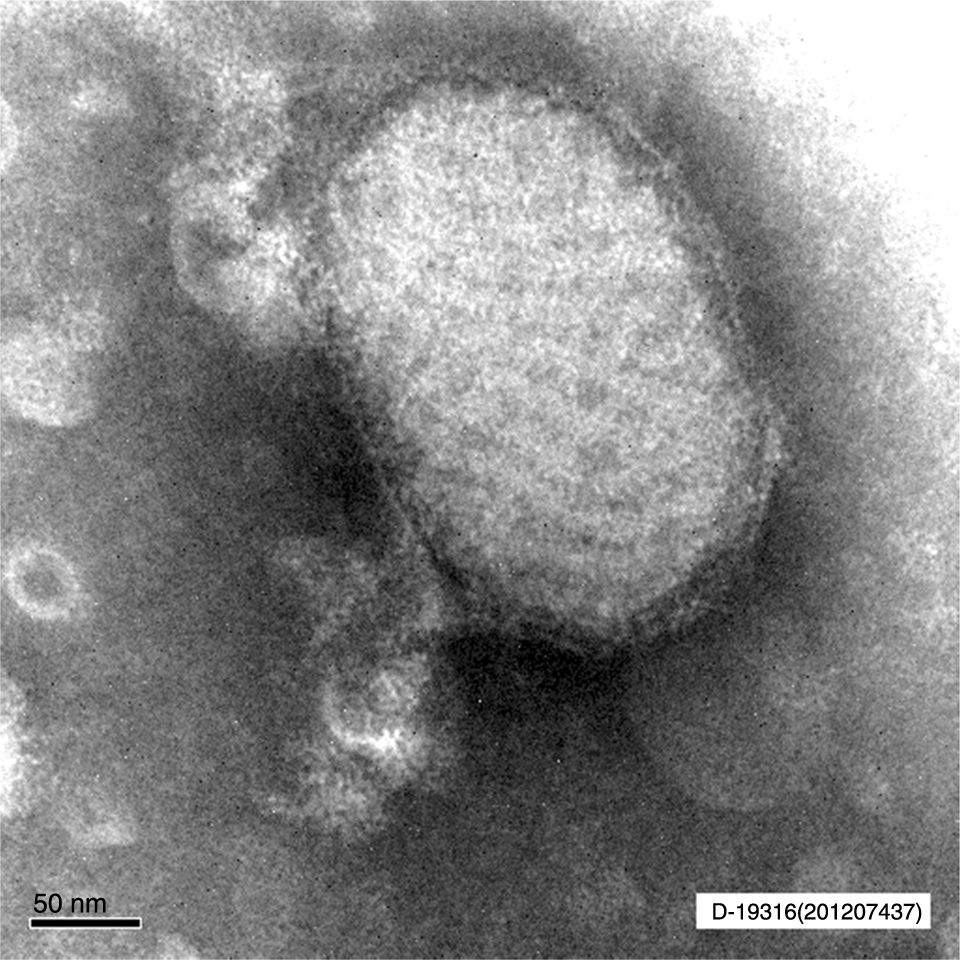

Clinical courseIn the anatomic-pathological analysis of the biopsy of the lesion, epidermal necrosis and proliferation in the dermis of numerous vessels with mixed inflammatory infiltrate were observed. In the National Centre of Microbiology, by means of electron microscopy, particles of parapoxvirus (Figs. 2 and 3) were observed.

The milker's nodule, also called the pseudo-virus of the cattle or milkmaid blisters1 is a benign viral infection produced by the Pseudocowpox virus, of the genus Parapoxvirus (PPV), enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses. It is a zoonosis of universal distribution of people in contact with livestock.2–4 The disease was described by Kaempfer in 1896, and the virus was isolated for the first time in cell cultures by Friedman-Kein.1 The genus of PPVs belongs to the Poxviridae family, and there are 4 types of species: Parapoxvirus ovis or Orf, Parapoxvirus bovis 1 (bovine papular stomatitis), Parapoxvirus bovis 2 (milker's nodule) and Parapoxvirus of Red Deer in New Zealand.5

Contagion occurs by contact with the nasal area or the udders of infected cattle, or by handling their meat,3 without any human-to-human transmission.2 The most common are lesions in the upper limbs, with atypical locations such as the face.5

After 4–15 days of incubation, one to five skin lesions appear at the point of inoculation.2,3 It lasts for 4–8 weeks, starting as a reddish maculopapular lesion, with centrifugal growth, which evolves into an exudative ulcer with an erythematous halo, ending in a papillomatous phase of dry and dark healing tissue that resolves with hardly any residual signs.2–4 The absence of locoregional lymphadenopathies and systemic symptoms is characteristic,1,3,5 only observed in some immunosuppressed subjects or in lesions complicated by bacterial superinfection, which is the most frequent complication.2,3 The infection leaves lasting immunity.1

Diagnosis is based on epidemiological history, histopathology, demonstration of viral particles by electron microscopy, virus detection in tissue samples by PCR or demonstrating neutralising antibodies.3,4

In histopathology, hyperkeratosis and acanthosis can be observed in the epidermis, and intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions. A mononuclear and eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate is observed in the dermis.3

For the differential diagnosis, other PPV infections will be considered, such as Orf, which is clinically indistinguishable, but caused by a different species. Also known as contagious ecthyma or contagious pustular dermatitis, which is transmitted by contact with saliva of infected sheep and goats, and infection is unusual when processing their meat.2,4 We will also consider infections from atypical mycobacteria, cutaneous tuberculosis, brown recluse spider bite, sporotrichosis, tularaemia, anthrax, syphilis, cattle hair granuloma, herpetic whitlow and ecthyma.1–3

In general, treatment is not necessary because the lesion resolves on its own. Local hygiene should be sought and signs of superinfection monitored if topical antibiotic therapy is necessary.1 Only in immunocompromised patients could other topical alternatives such as imiquimod be applied.2 Sick animals should be isolated and handled with gloves, and strict hand hygiene should be maintained.1 There is a veterinary vaccination.1

The clinical characteristics, the observation of the PPV, the microbiological analysis and the epidemiology led us to define the case as milker's nodule. Although increasingly less frequent in our setting, the absence of general symptoms and spontaneous resolution means that it eludes health care, and is therefore probably an under-reported entity.3

Special thanks to Dr Mar Lago of the Department of Dermatology and Pathology of the Hospital Universitario La Paz-Cantoblanco-Carlos III.

Please cite this article as: de la Calle-Prieto F, Romero Gómez MP, Cuevas Beltrán L, Bru Gorraiz FJ. Nódulo indoloro localizado en la mano. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:249–250.