Community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus (SA) bacteraemia is a common cause of hospitalisation in children. The occurrence of secondary foci (SF) of SA infection is associated with higher morbidity and mortality.

ObjectivesTo identify risk factors for SF of infection in children with community-acquired SA bacteraemia.

Material and methodsProspective cohort. All children aged from 30 days to 16 years admitted to a paediatric referral hospital between January 2010 and December 2016 for community-acquired infections, with SA isolated in blood cultures, were included. Microbiological, demographic and clinical characteristics were compared, with or without SF infection after 72h of hospitalisation.

ResultsA total of 283 patients were included, 65% male (n=184), with a median age of 60 months (IQR: 30–132). Seventeen per cent (n=48) had at least one underlying disease and 97% (n=275) had some clinical focus of infection, the most common being: osteoarticular 55% (n=156) and soft tissue abscesses 27% (n=79). A total of 65% (n=185) were resistant to methicillin. A SF of infection was found in 16% of patients (n=44). The SF identified were pneumonia 73% (n=32), osteoarticular 11% (n=5), soft tissue 11% (n=5) and central nervous system 5% (n=2). In the multivariate analysis, the persistence of positive blood cultures after the fifth day (OR: 2.40, 95%CI: 1.07–5.37, p<0.001) and sepsis (OR: 17.23, 95%CI 5.21–56.9, p<0.001) were predictors of SF. There was no association with methicillin sensitivity.

ConclusionsIn this cohort, methicillin-resistant SA infections predominated. The occurrence of SF of infection was associated with the persistence of bacteraemia after the fifth day and sepsis on admission.

La bacteriemia por Staphylococcus aureus (SA) adquirida en la comunidad representa una causa frecuente de ingreso en niños. La aparición de focos secundarios (FS) condiciona una mayor morbimortalidad.

ObjetivosIdentificar factores de riesgo de aparición de FS de infección en niños con bacteriemia por SA de la comunidad.

Material y métodosCohorte prospectiva. Desde enero de 2010 a diciembre de 2016 se incluyeron todos los niños (de 30 días a 16 años), hospitalizados en un hospital pediátrico de derivación por infecciones adquiridas en la comunidad, con aislamiento de SA en hemocultivos. Se compararon características microbiológicas, demográficas y clínicas según presentaran o no FS de infección tras 72h de hospitalización.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 283 niños, el 65% varones (n=184), con una mediana de edad de 60 meses (RIC: 30-132). El 17% (n=48) tenían alguna enfermedad de base y el 97% (n=275) un foco clínico de infección, siendo los más frecuentes: osteoarticular el 55% (n=156) y abscesos de partes blandas el 27% (n=79). El 65% (n=185) eran SA resistentes a meticilina. Presentaron FS el 16% de los pacientes (n=44): neumonía el 73% (n=32), osteoarticular el 11% (n=5), partes blandas el 11% (n=5) y sistema nervioso central el 5% (n=2). En el análisis multivariado fueron predictores de FS la persistencia de hemocultivos positivos tras el quinto día (OR: 2,40; IC95%: 1,07-5,37; p<0,001) y la sepsis (OR: 17,23; IC95%: 5,21-56,9; p<0,001). No hubo asociación con la sensibilidad a la meticilina.

ConclusionesEn esta cohorte predominaron las infecciones por SA resistente a la meticilina. La aparición de FS se asoció con la persistencia de la bacteriemia después del quinto día y la sepsis al ingreso.

Staphylococcus aureus (SA) infections have a high incidence in paediatrics. While they are usually mild skin and soft-tissue infections, they sometimes cause serious conditions such as pneumonia and sepsis.1 In serious forms the pathogen is usually identified in blood cultures. Bacteraemia usually has a longer duration and is associated with higher morbidity compared to other pathogens. SA produces variable amounts of cytotoxic proteins such as alpha-toxin and Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL), which are associated with more serious clinical forms. A longer duration of positive blood cultures has been reported in patients with undrained suppurative foci, inadequate treatment and community-acquired methicillin-resistant SA (MRSA).2,3 In these patients with prolonged SA bacteraemia, the appearance of secondary foci of infection is not uncommon and is associated with greater morbidity and mortality4,5 as well as prolonged intravenous antibiotic treatment time.6

The objectives of this study are to report the epidemiological characteristics and frequency of appearance of secondary foci of infection in a cohort of children with community-acquired SA bacteraemia and to identify the risk factors associated with the appearance of these secondary foci.

Materials and methodsAll patients with SA bacteraemia were prospectively enrolled from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2016. The inclusion criteria were as follows: being over 30 days and under 16 years of age, having been hospitalised at Hospital de Pediatría Prof. Dr. Juan P. Garrahan due to community-acquired infections, and having had at least one blood culture with SA growth taken within 48h of admission. The following patients were excluded: those who had been admitted for at least 24h in the last six months, those who visited a healthcare-related centre at least weekly, and those who had a long-term catheter or lived in closed communities. The hospital where the study was conducted is a tertiary care centre in Buenos Aires, Argentina. This centre cares for patients who visit of their own accord or are referred from other institutions throughout the country. The automated BacT/ALERT 3D system was used to process blood cultures. SA was identified and typed using conventional and automated microbiological tests according to the current operating procedures at the microbiology laboratory. Methicillin resistance was determined by the disc diffusion method with cefoxitin discs (30μg), as were rifampicin resistance (5μg), gentamicin resistance (10μg), co-trimoxazole resistance (25μg), erythromycin resistance (15μg) and clindamycin resistance (2μg). In all cases, antibiograms were performed by diffusion in Müeller-Hinton agar with incubation at 37°C for 24h. Antibiograms were interpreted according to current Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines.5 Inducible clindamycin resistance was identified by placing the disc of this antibiotic 25mm away from the erythromycin disc in the antibiogram. The minimum inhibitory concentration of vancomycin was determined by the gradient diffusion method using Etest® strips.

Data on patients’ medical history as well as clinical characteristics and clinical course were recorded in a database. Patients were admitted to the cohort on the day of their hospital admission and remained in follow-up until their medical discharge. The microbiological characteristics of the patients (methicillin resistance, number of positive blood cultures) were compared, as were their clinical characteristics based on whether or not they presented a secondary focus of infection 72h following documentation of bacteraemia. The clinical characteristics evaluated were gender; age (in months); history of use of antibiotics or immunosuppressants in the last month; presence of comorbidities; clinical focus of infection and its location; documentation of fever, sepsis or septic shock on admission; appearance of deep vein thrombosis; requirements for surgery or surgical drainage and days elapsed up to that procedure; admission to intensive care units or mechanical respiratory assistance; appearance of a secondary focus of infection and type of focus; days elapsed up to blood cultures becoming negative; and definitive empirical treatment indicated and its parenteral and oral duration. Length of stay and mortality related to infection were also recorded. Median white blood cell, haemoglobin and platelet levels, as well as C-reactive protein levels, were evaluated on admission.

DefinitionsSecondary focus of infection: any clinical focus of infection not present at the time of patient hospitalisation and manifesting within 72h of the date of positive blood cultures.

Duration of bacteraemia: time in days elapsed since the start of adequate antibiotic treatment and the date of the first negative blood cultures.

Empirical treatment: antibiotic treatment indicated with no information on blood culture results.

Definitive treatment: antibiotic treatment indicated after an antibiotic susceptibility report is received from microbiology.

Persistent bacteraemia: presence of positive blood cultures following the fifth day of adequate antibiotic treatment.

Sepsis: life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a disproportionate host response to an infection, with hypotension reversible with IV fluid administration.7

Categorical variables were expressed in terms of percentages, and continuous variables were expressed in terms of medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Continuous variables were analysed using the t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on their distribution. The chi-squared test was used for comparing categorical variables.2 The odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and p value for each group were calculated to measure the strength of association with the appearance of a secondary focus of infection. A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Variables with a p value <0.2 in the bivariate analysis and those which, due to their clinical significance, required testing in the multiple model were included in the multivariate model. The Stata program (version 10.0) was used for analysis.

Ethical considerations: at the start of the follow-up period, the patients were informed of the study and invited to participate. Data confidentiality and the utmost discretion with respect to patient identification were guaranteed. The characteristics of the study were explained to the patients and their family members. Routine practice indicated in each case was not modified by this protocol.

ResultsIn the study period, 283 patients with blood cultures with SA growth were enrolled. Their median age was 60 months (IQR: 30–132), and 65% (n=184) were males. At least one underlying disease was present in 17% (n=48). The underlying diseases were atopic dermatitis in 11% (n=30), history of repeated bronchial obstruction in 5% (n=13) and other in 1% (n=5).

At the time of admission, 97% had at least one clinical focus of infection (n=275). The foci of infection most commonly diagnosed on admission were: osteoarticular in 56% (n=156), soft-tissue abscesses in 28% (n=79), pneumonia with effusion in 7% (n=21) and endocarditis in 2% (n=7). All patients received adequate empirical treatment: 28% received empirical vancomycin (n=79), 67% received empirical clindamycin (n=191) and 5% received vancomycin and clindamycin (n=13). Empirical treatment was combined with third-generation cephalosporins in 41% of patients (n=117).

MRSA was identified in 65% (n=185). Clindamycin resistance was documented in 8% of patients (n=22). The median duration of bacteraemia was five days (IQR: 3–5 days). Of the patients in the cohort, 64% required some sort of surgery (n=180). Intensive care unit admission occurred in 20% of cases (n=56). Death related to infection occurred in 5% of cases (n=13). The median length of stay was 15 days (IQR: 11–28).

A secondary focus of infection was identified in 16% of the patients in the cohort (n=44). The most common were pneumonia in 73% (n=32), osteoarticular infection in 11% (n=5), soft-tissue infection in 11% (n=5) and central nervous system disorders in 5% (n=2).

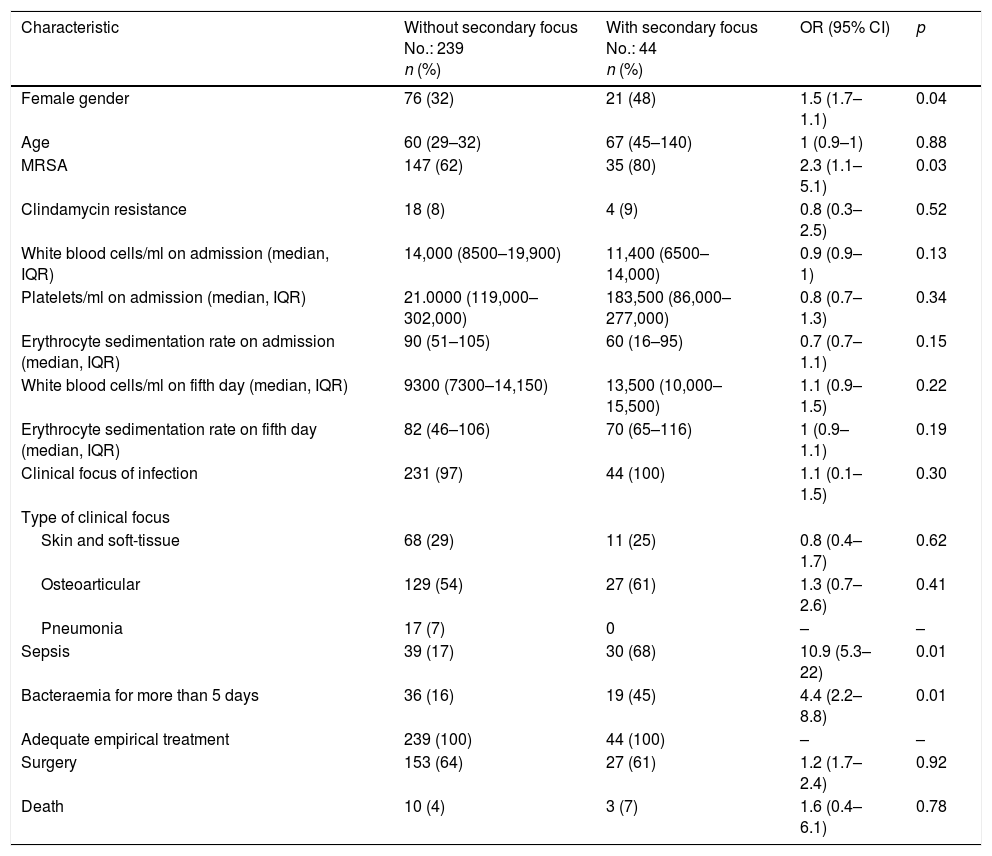

A bivariate analysis (Table 1) found the following to be associated with the appearance of secondary foci of infection: female gender (OR: 1.5; 95% CI: 1.7–1.1; p=0.04), MRSA bacteraemia (OR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.1–5.1; p=0.03), larger number of positive blood cultures (OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.4–2.1; p<0.01), persistence of bacteraemia after the fifth day of adequate treatment (OR: 4.4; 95% CI: 2.2–8.8; p<0.01) and sepsis (OR: 10.9; 95% CI: 5.3–22.6; p<0.1). The bivariate analysis found no association with age, susceptibility to clindamycin or type of clinical focus on admission.

Clinical characteristics. Bivariate analysis.

| Characteristic | Without secondary focus No.: 239 n (%) | With secondary focus No.: 44 n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 76 (32) | 21 (48) | 1.5 (1.7–1.1) | 0.04 |

| Age | 60 (29–32) | 67 (45–140) | 1 (0.9–1) | 0.88 |

| MRSA | 147 (62) | 35 (80) | 2.3 (1.1–5.1) | 0.03 |

| Clindamycin resistance | 18 (8) | 4 (9) | 0.8 (0.3–2.5) | 0.52 |

| White blood cells/ml on admission (median, IQR) | 14,000 (8500–19,900) | 11,400 (6500–14,000) | 0.9 (0.9–1) | 0.13 |

| Platelets/ml on admission (median, IQR) | 21.0000 (119,000–302,000) | 183,500 (86,000–277,000) | 0.8 (0.7–1.3) | 0.34 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate on admission (median, IQR) | 90 (51–105) | 60 (16–95) | 0.7 (0.7–1.1) | 0.15 |

| White blood cells/ml on fifth day (median, IQR) | 9300 (7300–14,150) | 13,500 (10,000–15,500) | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.22 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate on fifth day (median, IQR) | 82 (46–106) | 70 (65–116) | 1 (0.9–1.1) | 0.19 |

| Clinical focus of infection | 231 (97) | 44 (100) | 1.1 (0.1–1.5) | 0.30 |

| Type of clinical focus | ||||

| Skin and soft-tissue | 68 (29) | 11 (25) | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.62 |

| Osteoarticular | 129 (54) | 27 (61) | 1.3 (0.7–2.6) | 0.41 |

| Pneumonia | 17 (7) | 0 | – | – |

| Sepsis | 39 (17) | 30 (68) | 10.9 (5.3–22) | 0.01 |

| Bacteraemia for more than 5 days | 36 (16) | 19 (45) | 4.4 (2.2–8.8) | 0.01 |

| Adequate empirical treatment | 239 (100) | 44 (100) | – | – |

| Surgery | 153 (64) | 27 (61) | 1.2 (1.7–2.4) | 0.92 |

| Death | 10 (4) | 3 (7) | 1.6 (0.4–6.1) | 0.78 |

CI: confidence interval (95%); IQR: interquartile range; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; OR: odds ratio.

The multivariate model identified the following as predictors of the appearance of a secondary focus of infection: persistence of positive blood cultures after the fifth day (OR: 2.40; 95% CI: 1.07–5.37; p<0.001) and sepsis (OR: 17.2; 95% CI: 5.2–56.9; p<0.001). Adjusting for the other variables in the model, no association was found between methicillin resistance and the appearance of secondary foci.

DiscussionSA infections represent a common reason for paediatric visits. They usually present as mild skin and soft-tissue infections but sometimes require admission, intravenous antibiotic treatment and surgical procedures.8

The most serious clinical forms of infection may present with bacteraemia. Blood cultures are positive in 5% of children with community-acquired SA infections.9 The median duration of SA bacteraemia reported in the literature is 3–5 days, consistent with the study conducted.10 Prolonged bacteraemia has been linked to late drainage of suppurative foci, inadequate antibiotic treatment and unremoved intravascular devices (catheters, prostheses).11 A longer duration of bacteraemia results in a prolonged hospital stay and prolonged use of antibiotics.12

In this study, SA infections occurred in children without the risk factors reported in adults with staphylococcus infections.13 Methicillin resistance was also not associated with underlying diseases. As in other publications, MRSA isolates predominated. In our setting, the reported rate of methicillin resistance in community-acquired SA is 65%.14 The frequency of appearance of secondary foci of infection in patients with SA bacteraemia reported in other studies is 2–25%.15,16 In a study conducted by Praino et al.,17 the frequency of metastatic foci of infection in children with blood cultures positive for SA was 15%. In accordance with the literature, in this study it was 16%. A cohort study of 186 patients with SA bacteraemia associated secondary foci of infection and a low dose of antibiotic with the persistence of positive blood cultures.5 Another study conducted in children also found a link between a secondary focus and persistent bacteraemia.15 In the cohort presented, the appearance of secondary foci of infection was statistically associated with a longer duration of bacteraemia and haemodynamic compromise as a form of presentation.

The question of which are true SA virulence factors has been debated in the literature. Some authors have proposed PVL as a main virulence factor.18,19 Sicot et al. evaluated the association between mortality and methicillin resistance in patients with pneumonia due to PVL-producing SA in France. No link was found between methicillin resistance and mortality.20 In SA strains in this cohort, the presence of PVL was not systematically evaluated. However, a predominance of ST5-IV and ST30-IVclones, both PVL-producing in community-acquired SA infections, has been reported in Argentina.21

Other factors associated with a worse prognosis in patients with SA infections are antibiotic resistance,22 a higher minimum inhibitory concentration23,24 and other toxins synthesised by SA.25 As in other publications,4,15 no statistical association was found in the cohort presented between methicillin resistance and the appearance of secondary foci of infection.

The association between adequate empirical antibiotic treatment and the prognosis for SA bacteraemia has been widely debated in the literature.26,27 In a cohort of 510 patients with SA bacteraemia, Paul et al.28 reported a statistical association between 30-day mortality and inadequate empirical treatment. Thanks to algorithms for diagnosis and treatment of skin, soft-tissue and osteoarticular infections at the institution and multidisciplinary management with Infectious Diseases, all patients in this cohort had adequate empirical treatment. That is why this variable could not be examined as a prognostic factor. Implementation of sets of measures including clinical practice guidelines and an early visit to an infectious disease physician have been shown to improve the prognosis and reduce mortality in patients with SA bacteraemia.29

This study enabled children at highest risk of the appearance of secondary foci in a cohort of healthy children from the community to be identified. In patients with SA bacteraemia with sepsis as a form of presentation and a greater duration of bacteraemia, a comprehensive search for other foci of infection should be conducted, regardless of antibiotic susceptibility. Pneumonia was the main metastatic focus of SA infection in this cohort. Even though this evidence derives from a multivariate model applied to a prospective cohort of patients, statistical association does not infer causality. The main weakness of the study is the risk of inverse causality: this study does not explain whether a greater duration of bacteraemia and sepsis leads to the appearance of a secondary focus, or vice versa.

In conclusion, MRSA infections predominated in this cohort. Secondary foci of infection were seen in 16% of children with SA bacteraemia. The most common secondary focus was pneumonia. The appearance of secondary foci of infection was associated with the persistence of bacteraemia after the fifth day and sepsis on admission.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Perez MG, Martiren S, Escarra F, Reijtman V, Mastroianni A, Varela-Baino A, et al. Factores de riesgo de focos secundarios de infección en niños con bacteriemia por Staphylococcus aureus adquirida en la comunidad. Estudio de cohorte 2010-2016. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:493–497.