Norovirus (NoV) is the leading cause of outbreaks of gastroenteritis in humans worldwide, especially in children in the post-rotavirus vaccine era.1 Significantly, the frequency has also increased in institutionalized and hospitalized population, immunocompromised patients and extreme ages.2 Investigations of outbreaks have shown that the majority of transmissions are by direct contact with individuals carrying the virus, water, aerosols, contaminated food, and due to environmental contamination.3 The incubation period is short (12–48h), showing a higher incidence in autumn and winter. Typical clinical manifestations are vomiting and diarrhoea, and paediatric patients are more liable to have dehydration requiring hospitalization.1 Genetically, NoV has been classified into six genogroups (genogroup I [GI] to genogroup VI [GVI]), of which GI, GII, and GIV can infect humans.4 The genogroups are further classified into 9 GI, 22 GII, and 2 GIV genotypes.4,5 Although the GII.4 genotype is currently responsible for 60–90% of outbreaks worldwide,1 new GII.4 variants emerge every 2–3 years and become the dominant strains during the new season.6

On October 2014 an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis in a boarding school in Zamora (Castile and Leon, Spain) was reported to the local public health authority (LPHA). An outbreak investigation was conducted to identify the most likely causative agent and mode of transmission and to implement control measures. Given the importance of an accurate and early result, we used for the first time at our Laboratory of Microbiology molecular techniques for the NoV detection and we assessed, at the same time, their utility for the diagnosis of subsequent outbreaks.

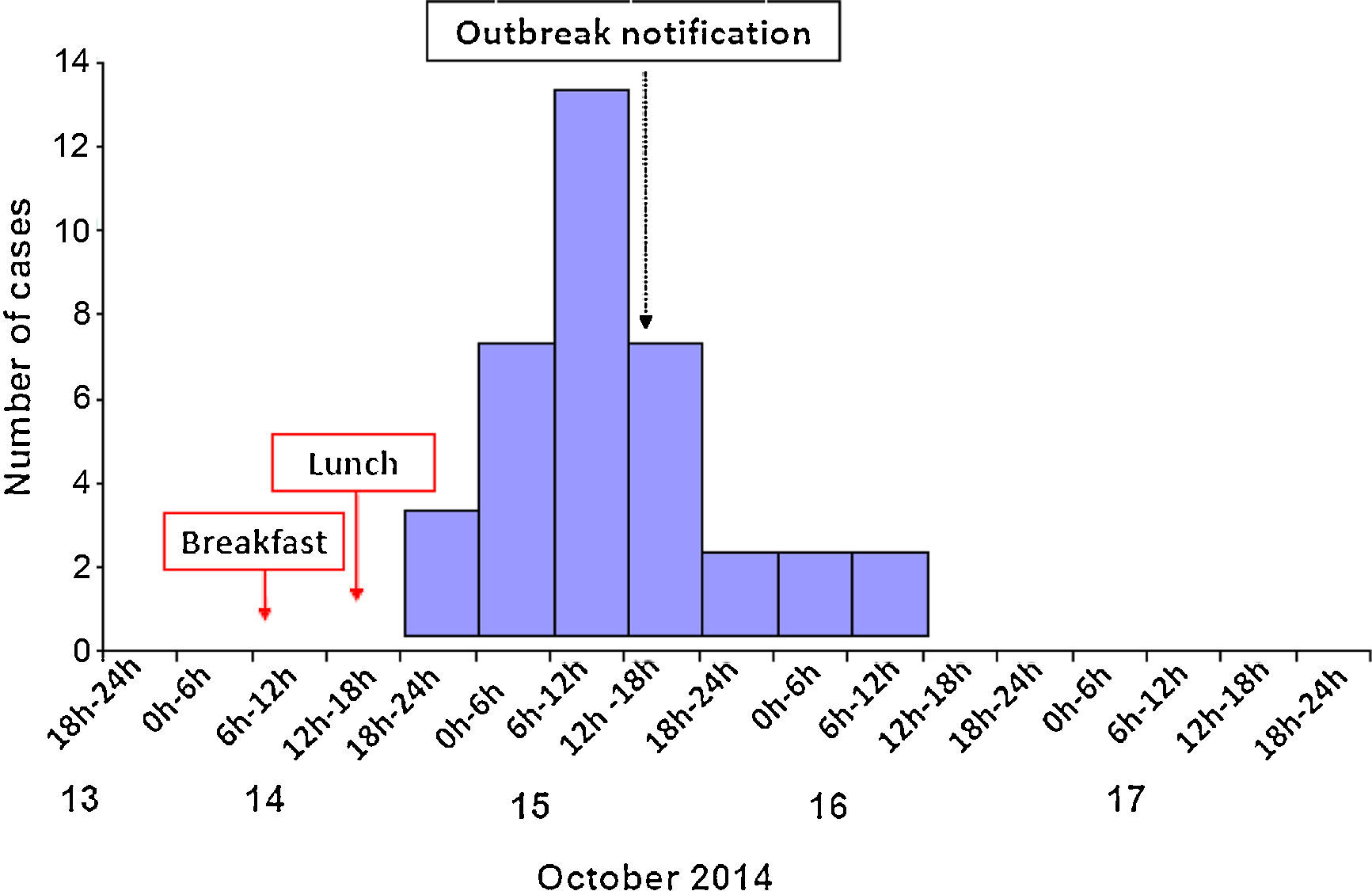

LPHA inspected the school premises and conducted a retrospective analysis using a structured questionnaire on demographic data, symptoms, food consumption and other possible risk factors. An outbreak case was defined as a person attending the affected institution who presented diarrhoea, vomiting or abdominal pain from 14 to 16 October 2014.

A total of 36 students (69.4% male, median age 15 years (12–19)) developed symptoms, whereas staff was not affected. The overall attack rate was 19.9% with no significant sex-related differences. The most frequent symptoms were abdominal cramps (97.2%), vomiting (91.7%) and neurological symptoms such as headache (83.3%). Diarrhoea (52.8%) and fever (19.4%) were less frequent. Fig. 1 shows the number of cases by date of onset of symptoms. The outbreak was self-limiting in 3 days and nobody was hospitalised.

Stool samples from 2 cases were screened for the most frequent enteropathogenic bacteria by selective and differential media and for rotavirus and enteric adenoviruses antigen by an immunochromatographic technique (ICT) (Balea Norovirus®). Simultaneously, samples were tested by a real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT RT-PCR) (Xpert® Norovirus, Cepheid) for qualitative detection and differentiation of NoV GI/GII and by an ICT for the same genogroups. In both samples NoV ICT was negative but the RT RT-PCR detected NoV GII. Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Aeromonas, Hafnia and Campylobacter and viral enteropathogens were discarded. Food samples were negative for enteropathogenic bacteria (no viruses were studied) at the LPH laboratory.

Different outbreaks due to NoV in closed institutions have been reported in Spain. Navarro et al.7 described NoV GII affecting patients, staff members, and their relatives in a long-term-care unit and suggesting a person-to-person spread. The same genogroup was detected in Majorca, associated with the children's club of a hotel.8 A food-borne NoV outbreak was reported among staff at a hospital in Barcelona9 and a water-borne one in a factory in the Basque Country.10

Epidemiological features, microbiological results and no isolation of other pathogens confirmed that the outbreak was caused by NoV GII, with probable person-to-person transmission. This was the first time a NoV outbreak in Zamora was laboratory confirmed, although source remained unclear. We emphasize that the presence of NoV should always be suspected and investigated in gastroenteritis outbreaks including those of closed institutions in the absence of the usual pathogens. Given the low sensitivity of the ICTs for NoV detection, molecular techniques could be prioritized in case of epidemiological suspicion. Therefore, we recommend the implementation of molecular techniques, with high sensitivity and specificity, no time-consuming management and fast results, despite the high cost, to determine the actual frequency of NoV both on sporadic cases as well as outbreaks.

FundingNo funding has been received for this research.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interest.