Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) is the most common cause of genital herpes (GH), but genital infection by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is increasing. The aim of this study was to analyze and compare epidemiological characteristics of patients with GH.

MethodsRetrospective study conducted from January 2004 to December 2015 in patients with GH attended at two Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) medical consultation of Bilbao-Basurto Integrated Health Organisation in Northern Spain. Patient's medical history was reviewed and data of interest was analyzed.

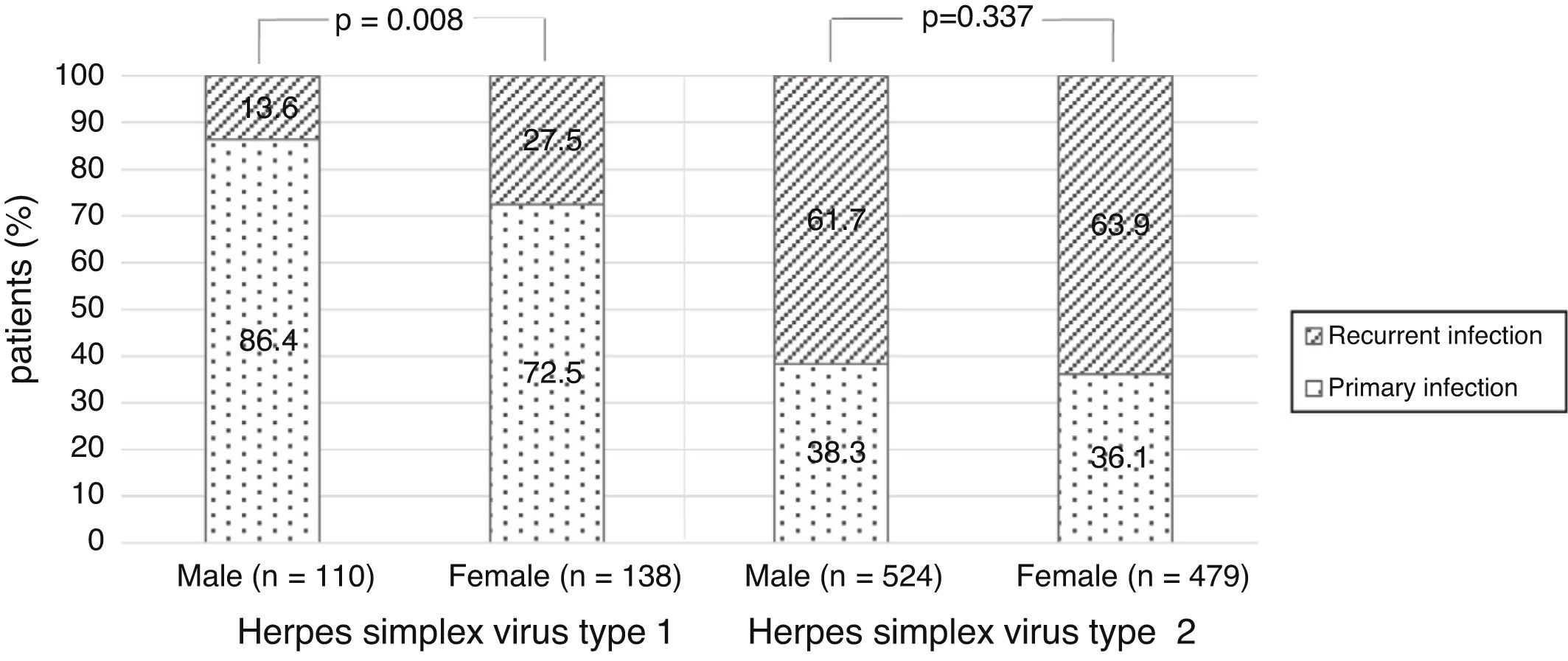

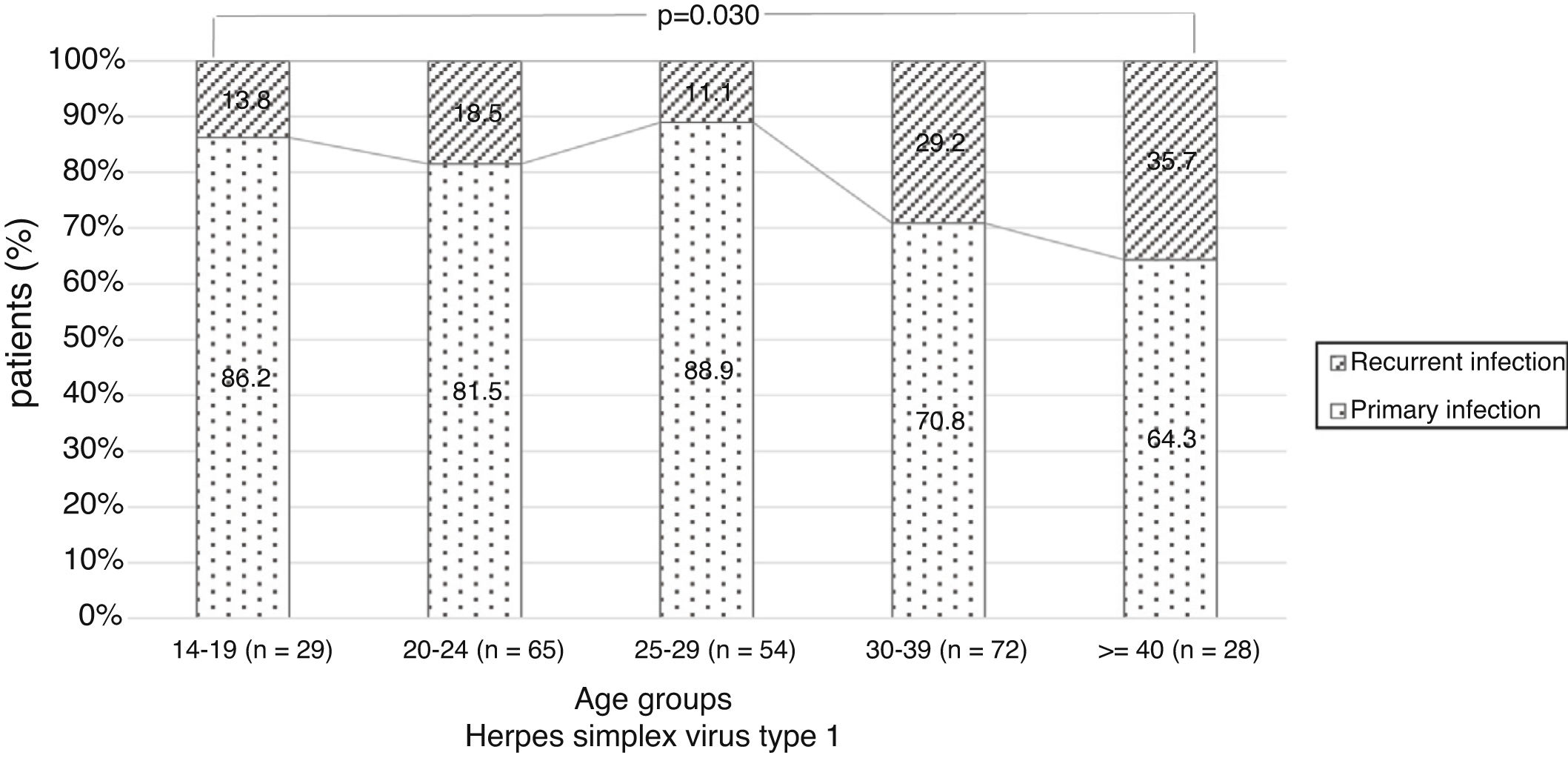

ResultsOne thousand three patients (524 male and 479 female) were reviewed. HSV-2 was detected in 74%. The proportion of HSV-1 increased during the study period, significantly in men (28% in 2004–2007 vs. 50% in 2012–2015). More female than male had HSV-1 infection (56% vs. 44%). The proportion of primary infection was higher among HSV-1 compared to HSV-2 (79% vs. 21%). Among the patients with HSV-1, primary infection was higher among men (86%) and in younger than 30 years. Recurrent GH was higher among HSV-2 infections (63%). In a multivariate model older age, geographic origin outside Spain, recurrent infection, prior contact with a partner's genital herpetic lesions, previous N. gonorrhoeae infection and prostitution were significantly associated with HSV-2 infection.

ConclusionsHSV-2 was the most common causative agent of GH, but the proportion of HSV-1 increased. Overall, antecedent of STD and sexual risk behaviors were more frequent in patients with genital HSV-2 infection.

El virus herpes simple tipo 2 (VHS-2) es la causa más frecuente de herpes genital (HG), pero la infección genital por el virus herpes simple tipo 1 (VHS-1) está en aumento. El objetivo del estudio fue analizar las características epidemiológicas de pacientes con HG.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo desde enero del 2004 hasta diciembre del 2015 de pacientes con HG atendidos en 2 consultas de enfermedades de transmisión sexual (ETS) en la Organización Sanitaria Integrada Bilbao-Basurto, en el norte de España. Se revisaron y analizaron los datos de interés de los pacientes.

ResultadosMil tres pacientes (524 hombres y 479 mujeres) fueron incluidos. El 74% tenía infección por VHS-2. El VHS-1 aumentó durante el periodo estudiado, significativamente en hombres (28% en 2004-2007 vs. 50% en 2012-2015). El VHS-1 fue mayor en mujeres en comparación con hombres (56% vs. 44%). La infección primaria fue más frecuente en los infectados con VHS-1 comparado con VHS-2 (79% vs. 21%). En pacientes con VHS-1, la infección primaria fue superior en hombres (86%) y en menores de 30 años. El 63% de las infecciones por VHS-2 fueron recurrencias. En el análisis multivariante, la edad, el origen extranjero, la recurrencia, el contacto previo con HG de la pareja sexual, la infección previa por Neisseria gonorrhoeae y la prostitución se asociaron con mayor riesgo de infección por VHS-2.

ConclusionesEl VHS-2 fue la causa principal del HG, pero la proporción de VHS-1 aumentó. El antecedente de ETS y las conductas sexuales de riesgo fueron predominantes en los pacientes con HG por VHS-2.

Genital herpes (GH) is a major cause of genital ulcer diseases particularly in developing countries1 and it has an important impact on physical and psychological morbidity and healthcare costs.2 During recent years the incidence of GH has increased due to social trends and demographic and migratory changes. The World Health Organization has estimated the prevalence of GH in 2012 at 500 million people worldwide. Of that group 417 million people aged 15–49 were infected with herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2).1

Herpes simplex viruses (HSV) can produce primary or recurrent infection. Primary genital infections are usually manifested of vesicles and ulcers of skin and mucous membrane lesions 4–7 days after sexual contact. Pain, dysuria, lymphadenopathy and fever are relatively common associated symptoms. Following the primary infection the virus establishes lifelong latency in sacral neural ganglions and the virus can reactivate from here causing recurrent infection. People with clinically manifest GH and people who shed HSV asymptomatically can transmit the virus to their sexual partners via direct contact during sexual intercourse.3 HSV-2 is the most frequent etiology of anogenital infections.4–7 However, during last three decades, the incidence of GH due to HSV-1 has increased in many developed countries. The principal reason for this epidemiological change is the decline in HSV-1 seroprevalence among children and adolescents due to improvements in living conditions, better hygiene and less crowding in families.8–10 The susceptible adolescent population in combination with earlier sexual debut and increased oral sex behaviors, can explain the high proportion of GH caused by HSV-1.5,11,12

Clinical manifestations and treatment are identical but it is important to identify the type of HSV that cause GH in order to make a differential diagnosis with other ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or other genital ulcerative dermatoses. The laboratory diagnosis of genital HSV infection is usually made by direct methods such as virus isolation or viral DNA detection in skin or mucous membrane swabs. The detection of virus-specific antibodies can confirm the diagnosis and it is helpful for the determination of stage of infection.

Furthermore, the evolution of the disease and some epidemiological or sexual risk factors are different in each HSV type.3 In general, GH due to HSV-1 is more common in young women, people who have oral sex without protection13 and men who have sex with men (MSM).11,13 Genital HSV-1 infection usually involves fewer recurrent episodes,14 so generally, symptomatic genital HSV-1 infection is primary infection.3 Genital HSV-2 infection is associated with more sexual risk factors, such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, prostitution and high number of sexual partners.14 The risk of transmission is high because recurrences are more frequent with genital HSV-2 infection.15

In this respect, it is interesting to know the change in the epidemiology of GH and the differences between types of HSV in our area. Thus, the aim of this study was to describe epidemiology, clinical characteristics and sexual behavior or risk factors of patients with GH treated at two STDs clinics in Bilbao, Spain.

Materials and methodsPatients and settingFrom January 2004 to December 2015, patients of two STD medical consultations of Bilbao-Basurto Integrated Health Organisation (IHO) in Spain were retrospectively identified. Approximately 350,000 people live in the metropolitan area that STD clinics served. Patients included were those with GH confirmed by direct microbiological methods. Specimens were skin and mucous membrane, urethral, cervical, rectal and vaginal swabs and urine. Conjunctival and oropharyngeal swabs were tested in patients with concurrent orofacial symptomatic herpes. Samples were collected with cotton swabs and inoculated into viral transport medium. Diagnosis test was virus isolation by cell culture and subsequent typing with immunofluorescence. Since 2009, in cases of negative viral culture, a commercial nucleic acid amplification test was performed to detect viral DNA. Samples were tested at microbiological department of Basurto University Hospital. Patients medical history was reviewed and the following information was collected: demographic data (age, gender, geographic origin), sexual behavior (preference, practices, risk factors, previous STDs), clinical data (symptomatology, previous contact with herpetic lesions), stage of infection, number of recurrent infections in a year, microbiological data (HSV type, samples, diagnostic method) and therapeutic information. The study was ethically approved by the ethical committee of Basurto University Hospital.

Statistical analysisThe qualitative variables were expressed with frequencies and percentages and the quantitative variables with mean and standard deviation (SD). The comparison of quantitative variables according to two-level categorical variables was analyzed by the Student's t-test or Wilcoxon test. Associations between quantitative variables and categorical variables with two or more categories were assessed by analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis test. Association between categorical variables was tested by the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Further, the logistic regression models were used to study factors associated with HSV-2 positive GH. First, univariate analyses were performed considering HSV-2 vs. HSV-1 as the dependent variable, and each demographic, clinic or behavioral as independent factors. Then, clinically relevant variables or variables significant at a level of p <0.15 in univariate analysis were analyzed into a multivariate logistic regression model to determine predictors associated with HSV-2 positive GH. In the final multivariate model only factors with p <0.05 were retained. The results for these analyses were expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS for Windows, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Carey, NC).

ResultsDemographic data1003 patients with 1516 samples were identified over a 12-year period. Most of samples were skin and mucous membrane swabs (87.9%) and generally diagnosed by virus isolation by cell culture (87.6%) (data not shown).

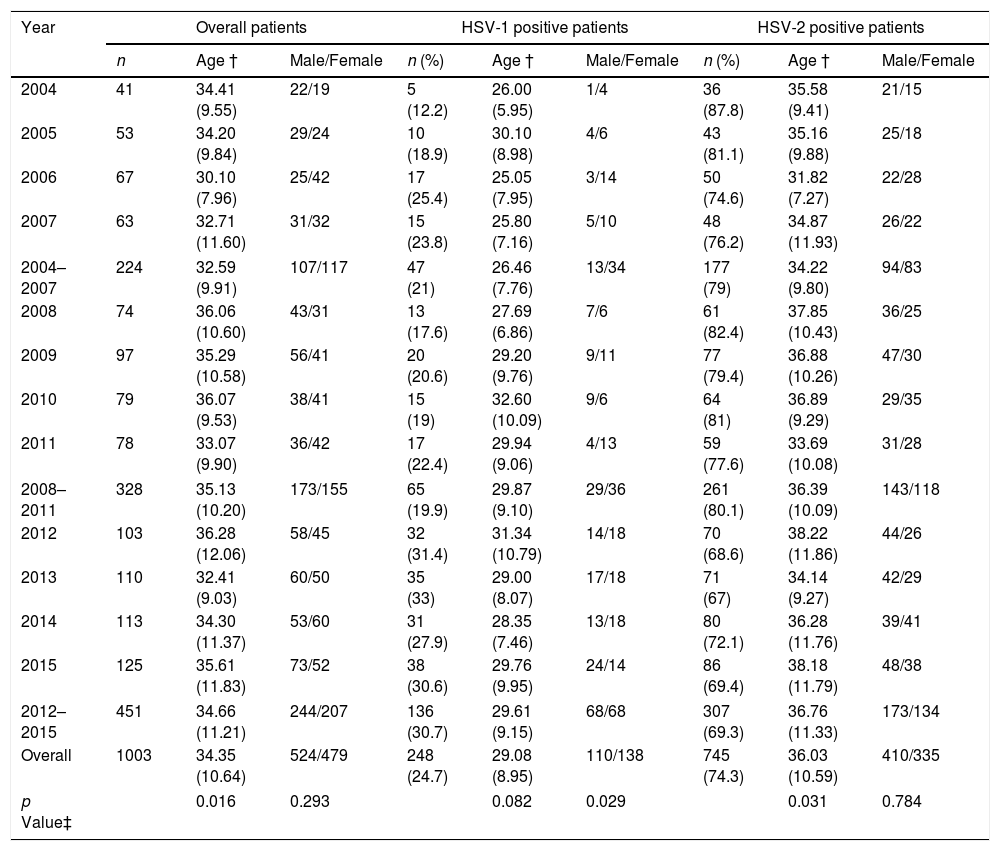

The mean age of the patients was 34.4 (SD, 10.6) years and 524 patients (52.2%) were male. 745 patients (74.3%) had genital HSV-2 infection, 248 patients (24.7%) by HSV-1 and 10 patients (1%) had GH due two types of HSV. The number of patients with GH increased during the study period from 41 patients in 2004 to 125 patients in 2015 (224 patients in 2004–2007 and 451 patients in 2012–2015). The incidence rate of microbiologically confirmed GH cases per annum and per 100,000 habitants varied between 13 cases in 2004 and 40 cases in 2015. The proportion of genital HSV-1 infection increased from 21% in 2004–2007 to 30.7% in 2012–2015 (p=0.001) (Table 1). The increase of male and female patients with GH due to HSV-1 remained consistent each year, but the proportion of HSV-1 positive male patients increased significantly from 27.7% in 2004–2007 to 50% in 2012–2015 (p=0.029) (Table 1).

Age and gender of patients with genital herpes from 2004 to 2015. HSV=herpes simplex virus; † Mean and standard deviation; ‡ Male vs. female and age compared by cohort of years.

| Year | Overall patients | HSV-1 positive patients | HSV-2 positive patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Age † | Male/Female | n (%) | Age † | Male/Female | n (%) | Age † | Male/Female | |

| 2004 | 41 | 34.41 (9.55) | 22/19 | 5 (12.2) | 26.00 (5.95) | 1/4 | 36 (87.8) | 35.58 (9.41) | 21/15 |

| 2005 | 53 | 34.20 (9.84) | 29/24 | 10 (18.9) | 30.10 (8.98) | 4/6 | 43 (81.1) | 35.16 (9.88) | 25/18 |

| 2006 | 67 | 30.10 (7.96) | 25/42 | 17 (25.4) | 25.05 (7.95) | 3/14 | 50 (74.6) | 31.82 (7.27) | 22/28 |

| 2007 | 63 | 32.71 (11.60) | 31/32 | 15 (23.8) | 25.80 (7.16) | 5/10 | 48 (76.2) | 34.87 (11.93) | 26/22 |

| 2004–2007 | 224 | 32.59 (9.91) | 107/117 | 47 (21) | 26.46 (7.76) | 13/34 | 177 (79) | 34.22 (9.80) | 94/83 |

| 2008 | 74 | 36.06 (10.60) | 43/31 | 13 (17.6) | 27.69 (6.86) | 7/6 | 61 (82.4) | 37.85 (10.43) | 36/25 |

| 2009 | 97 | 35.29 (10.58) | 56/41 | 20 (20.6) | 29.20 (9.76) | 9/11 | 77 (79.4) | 36.88 (10.26) | 47/30 |

| 2010 | 79 | 36.07 (9.53) | 38/41 | 15 (19) | 32.60 (10.09) | 9/6 | 64 (81) | 36.89 (9.29) | 29/35 |

| 2011 | 78 | 33.07 (9.90) | 36/42 | 17 (22.4) | 29.94 (9.06) | 4/13 | 59 (77.6) | 33.69 (10.08) | 31/28 |

| 2008–2011 | 328 | 35.13 (10.20) | 173/155 | 65 (19.9) | 29.87 (9.10) | 29/36 | 261 (80.1) | 36.39 (10.09) | 143/118 |

| 2012 | 103 | 36.28 (12.06) | 58/45 | 32 (31.4) | 31.34 (10.79) | 14/18 | 70 (68.6) | 38.22 (11.86) | 44/26 |

| 2013 | 110 | 32.41 (9.03) | 60/50 | 35 (33) | 29.00 (8.07) | 17/18 | 71 (67) | 34.14 (9.27) | 42/29 |

| 2014 | 113 | 34.30 (11.37) | 53/60 | 31 (27.9) | 28.35 (7.46) | 13/18 | 80 (72.1) | 36.28 (11.76) | 39/41 |

| 2015 | 125 | 35.61 (11.83) | 73/52 | 38 (30.6) | 29.76 (9.95) | 24/14 | 86 (69.4) | 38.18 (11.79) | 48/38 |

| 2012–2015 | 451 | 34.66 (11.21) | 244/207 | 136 (30.7) | 29.61 (9.15) | 68/68 | 307 (69.3) | 36.76 (11.33) | 173/134 |

| Overall | 1003 | 34.35 (10.64) | 524/479 | 248 (24.7) | 29.08 (8.95) | 110/138 | 745 (74.3) | 36.03 (10.59) | 410/335 |

| p Value‡ | 0.016 | 0.293 | 0.082 | 0.029 | 0.031 | 0.784 | |||

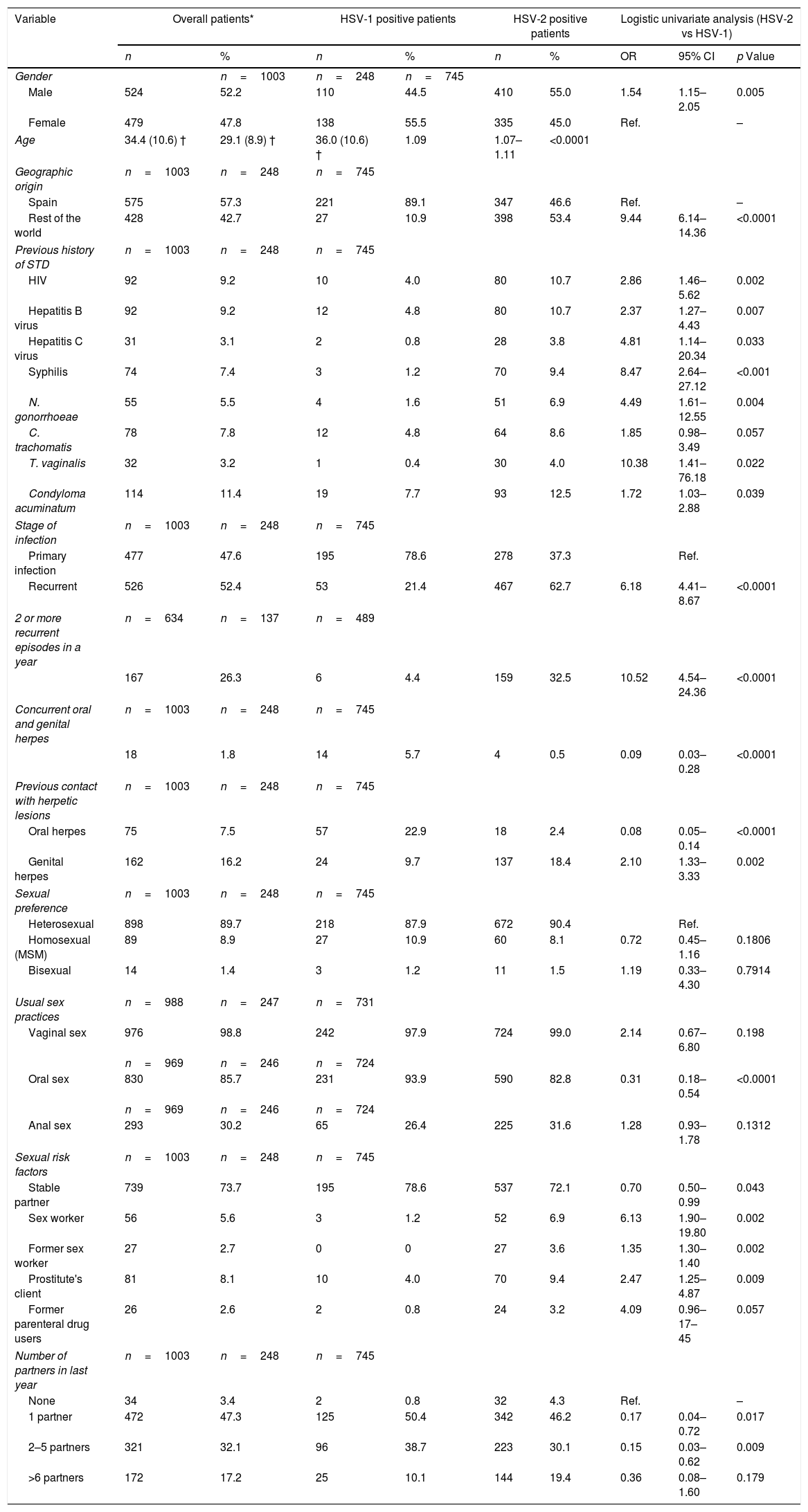

The mean age of patients with HSV-2 GH was 36.0 (SD, 10.6) years and 55% was male. Male patients and older were significantly associated with genital HSV-2 infection in the logistic univariate analysis comparing with patients with HSV-1 GH (p<0.01), which 55.5% was female and, in general, youngers (Table 2).

Comparison of demographic, microbiological, clinical and behavioral characteristics of patients with genital herpes according to the type of herpes simplex virus (logistic univariate analysis). HSV=herpes simplex virus; OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; STD=sexually transmitted disease; HIV=Human Immunodeficiency Virus; MSM=men who have sex with men; ‡ 10 patients had genital herpes with both types of HSV; † Mean and standard deviation; Ref.=reference group.

| Variable | Overall patients* | HSV-1 positive patients | HSV-2 positive patients | Logistic univariate analysis (HSV-2 vs HSV-1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Gender | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| Male | 524 | 52.2 | 110 | 44.5 | 410 | 55.0 | 1.54 | 1.15–2.05 | 0.005 |

| Female | 479 | 47.8 | 138 | 55.5 | 335 | 45.0 | Ref. | – | |

| Age | 34.4 (10.6) † | 29.1 (8.9) † | 36.0 (10.6) † | 1.09 | 1.07–1.11 | <0.0001 | |||

| Geographic origin | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| Spain | 575 | 57.3 | 221 | 89.1 | 347 | 46.6 | Ref. | – | |

| Rest of the world | 428 | 42.7 | 27 | 10.9 | 398 | 53.4 | 9.44 | 6.14–14.36 | <0.0001 |

| Previous history of STD | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| HIV | 92 | 9.2 | 10 | 4.0 | 80 | 10.7 | 2.86 | 1.46–5.62 | 0.002 |

| Hepatitis B virus | 92 | 9.2 | 12 | 4.8 | 80 | 10.7 | 2.37 | 1.27–4.43 | 0.007 |

| Hepatitis C virus | 31 | 3.1 | 2 | 0.8 | 28 | 3.8 | 4.81 | 1.14–20.34 | 0.033 |

| Syphilis | 74 | 7.4 | 3 | 1.2 | 70 | 9.4 | 8.47 | 2.64–27.12 | <0.001 |

| N. gonorrhoeae | 55 | 5.5 | 4 | 1.6 | 51 | 6.9 | 4.49 | 1.61–12.55 | 0.004 |

| C. trachomatis | 78 | 7.8 | 12 | 4.8 | 64 | 8.6 | 1.85 | 0.98–3.49 | 0.057 |

| T. vaginalis | 32 | 3.2 | 1 | 0.4 | 30 | 4.0 | 10.38 | 1.41–76.18 | 0.022 |

| Condyloma acuminatum | 114 | 11.4 | 19 | 7.7 | 93 | 12.5 | 1.72 | 1.03–2.88 | 0.039 |

| Stage of infection | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| Primary infection | 477 | 47.6 | 195 | 78.6 | 278 | 37.3 | Ref. | ||

| Recurrent | 526 | 52.4 | 53 | 21.4 | 467 | 62.7 | 6.18 | 4.41–8.67 | <0.0001 |

| 2 or more recurrent episodes in a year | n=634 | n=137 | n=489 | ||||||

| 167 | 26.3 | 6 | 4.4 | 159 | 32.5 | 10.52 | 4.54–24.36 | <0.0001 | |

| Concurrent oral and genital herpes | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| 18 | 1.8 | 14 | 5.7 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.09 | 0.03–0.28 | <0.0001 | |

| Previous contact with herpetic lesions | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| Oral herpes | 75 | 7.5 | 57 | 22.9 | 18 | 2.4 | 0.08 | 0.05–0.14 | <0.0001 |

| Genital herpes | 162 | 16.2 | 24 | 9.7 | 137 | 18.4 | 2.10 | 1.33–3.33 | 0.002 |

| Sexual preference | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| Heterosexual | 898 | 89.7 | 218 | 87.9 | 672 | 90.4 | Ref. | ||

| Homosexual (MSM) | 89 | 8.9 | 27 | 10.9 | 60 | 8.1 | 0.72 | 0.45–1.16 | 0.1806 |

| Bisexual | 14 | 1.4 | 3 | 1.2 | 11 | 1.5 | 1.19 | 0.33–4.30 | 0.7914 |

| Usual sex practices | n=988 | n=247 | n=731 | ||||||

| Vaginal sex | 976 | 98.8 | 242 | 97.9 | 724 | 99.0 | 2.14 | 0.67–6.80 | 0.198 |

| n=969 | n=246 | n=724 | |||||||

| Oral sex | 830 | 85.7 | 231 | 93.9 | 590 | 82.8 | 0.31 | 0.18–0.54 | <0.0001 |

| n=969 | n=246 | n=724 | |||||||

| Anal sex | 293 | 30.2 | 65 | 26.4 | 225 | 31.6 | 1.28 | 0.93–1.78 | 0.1312 |

| Sexual risk factors | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| Stable partner | 739 | 73.7 | 195 | 78.6 | 537 | 72.1 | 0.70 | 0.50–0.99 | 0.043 |

| Sex worker | 56 | 5.6 | 3 | 1.2 | 52 | 6.9 | 6.13 | 1.90–19.80 | 0.002 |

| Former sex worker | 27 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 3.6 | 1.35 | 1.30–1.40 | 0.002 |

| Prostitute's client | 81 | 8.1 | 10 | 4.0 | 70 | 9.4 | 2.47 | 1.25–4.87 | 0.009 |

| Former parenteral drug users | 26 | 2.6 | 2 | 0.8 | 24 | 3.2 | 4.09 | 0.96–17–45 | 0.057 |

| Number of partners in last year | n=1003 | n=248 | n=745 | ||||||

| None | 34 | 3.4 | 2 | 0.8 | 32 | 4.3 | Ref. | – | |

| 1 partner | 472 | 47.3 | 125 | 50.4 | 342 | 46.2 | 0.17 | 0.04–0.72 | 0.017 |

| 2–5 partners | 321 | 32.1 | 96 | 38.7 | 223 | 30.1 | 0.15 | 0.03–0.62 | 0.009 |

| >6 partners | 172 | 17.2 | 25 | 10.1 | 144 | 19.4 | 0.36 | 0.08–1.60 | 0.179 |

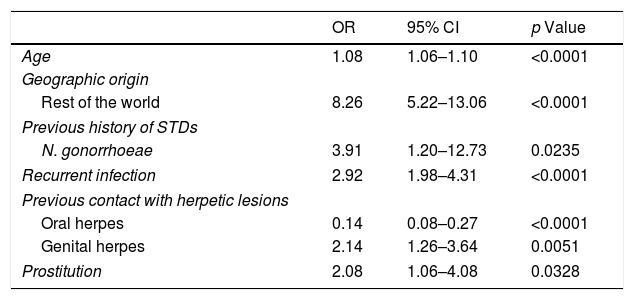

Regarding genital HSV-1 infection, 221 (89.1%) patients were Spanish and 398 (53.4%) of patients with HSV-2 GH were from other countries, especially from South America (p<0.0001) (Table 2). The geographic origin out of Spain was significantly associated with genital HSV-2 infection in the multivariate model (OR: 8.26 [95% CI: 5.22–13.06], p<0.0001) (Table 3).

Multivariable analysis for patients with HSV-2 genital herpes infection. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; STDs = sexually transmitted diseases;.

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.08 | 1.06–1.10 | <0.0001 |

| Geographic origin | |||

| Rest of the world | 8.26 | 5.22–13.06 | <0.0001 |

| Previous history of STDs | |||

| N. gonorrhoeae | 3.91 | 1.20–12.73 | 0.0235 |

| Recurrent infection | 2.92 | 1.98–4.31 | <0.0001 |

| Previous contact with herpetic lesions | |||

| Oral herpes | 0.14 | 0.08–0.27 | <0.0001 |

| Genital herpes | 2.14 | 1.26–3.64 | 0.0051 |

| Prostitution | 2.08 | 1.06–4.08 | 0.0328 |

Findings showed 898 (89.7%) patients were heterosexual, especially women (99.8%). Homosexual patients numbered 89 (8.9%) and all of them were male (p<0.0001). There was no significant differences in the sexual preference according to the type of HSV (p=0.3858) (data not shown). Nevertheless, in the stratified analysis of gender, heterosexual males were more frequent in the group of patients with HSV-2 infection (82.6%) and the proportion of MSM (24.5%) was higher in the group of HSV-1 infection (p=0.046) (additional table).

Most of the patients had stable partner (73.7%). The proportion of patients with sexual risk factors were higher in the group of HSV-2 infection compared with the group of HSV-1 infection (p<0.05) (Table 2). Prostitution was significantly associated with genital HSV-2 infection in the multivariate model (OR: 2.08 [95% CI: 1.06–4.08], p=0.0328) (Table 3).

Of the number of sex partners within a last year, 47.3% of patients with GH had only one sex partner. 144 patients (19.4%) with genital HSV-2 infection had more than six partners in comparison to 25 patients (10.1%) with HSV-1 infection with more than six partners (p=0.179) (Table 2).

Overall the most frequent way of transmitting the infection was vaginal sex (976, 98.8%), but oral sex was higher (93.9%) in patients with genital HSV-1 infection (p<0.0001). In fact, 57 patients (22.9%) with GH by HSV-1 had previous contact with oral herpetic lesions of sexual partner vs. 2.4% of patients with genital HSV-2 infection (p<0.0001); 137 patients (18.4%) with genital HSV-2 infection had previous contact with genital herpetic lesions vs. 9.7% patients with HSV-1 GH (p=0.002) (Table 2). This variable was significantly associated with genital HSV-2 infection in the multivariate model (OR: 2.14 [95% CI: 1.26–3.64], p=0.0051) (Table 3).

Clinical characteristicsThe most frequent symptom of GH was genital ulcerative lesions (84%). Other symptoms and signs such as pain (37.1%), local adenitis (29%), pruritus (26.6%), dysuria (13.7%) and fever (10.9%) were more common in patients with genital HSV-1 infection (p<0.05) (data not shown).

Genital ulcerative lesions (82.4%), pain (32.1%), local adenitis (24.6%), dysuria (11.8%) and fever (9.9%) were more frequent in patients with primary infection than in patients with recurrent infection (p<0.0001). In the same way, leucorrhea (11.5%) and cervicitis (5.9%) were more frequent in women with primary infection compared with recurrent infection (p<0.0001). Dysuria (20%), meatitis (6.4%) and proctitis (3.6%) were more prevalent in male with genital HSV-1 infection (p<0.05). Eighteen patients presented concurrent orofacial and anogenital symptomatic herpes (data not shown).

Serological results and anamnesis demonstrated that 526 patients (52.4%) were diagnosed of recurrent infection, most of them with HSV-2 infection (467, 62.7%) (Table 2). Primary infection was shown in 195 patients (78.6%) with HSV-1 infection in comparison with 37.3% of patients with HSV-2 GH (p<0.0001). The diagnosis of recurrent infection was significantly associated with genital HSV-2 infection in the univariate analysis and in the multivariate model (OR: 2.92 [95% CI: 1.98–4.31], p<0.0001) (Table 3).

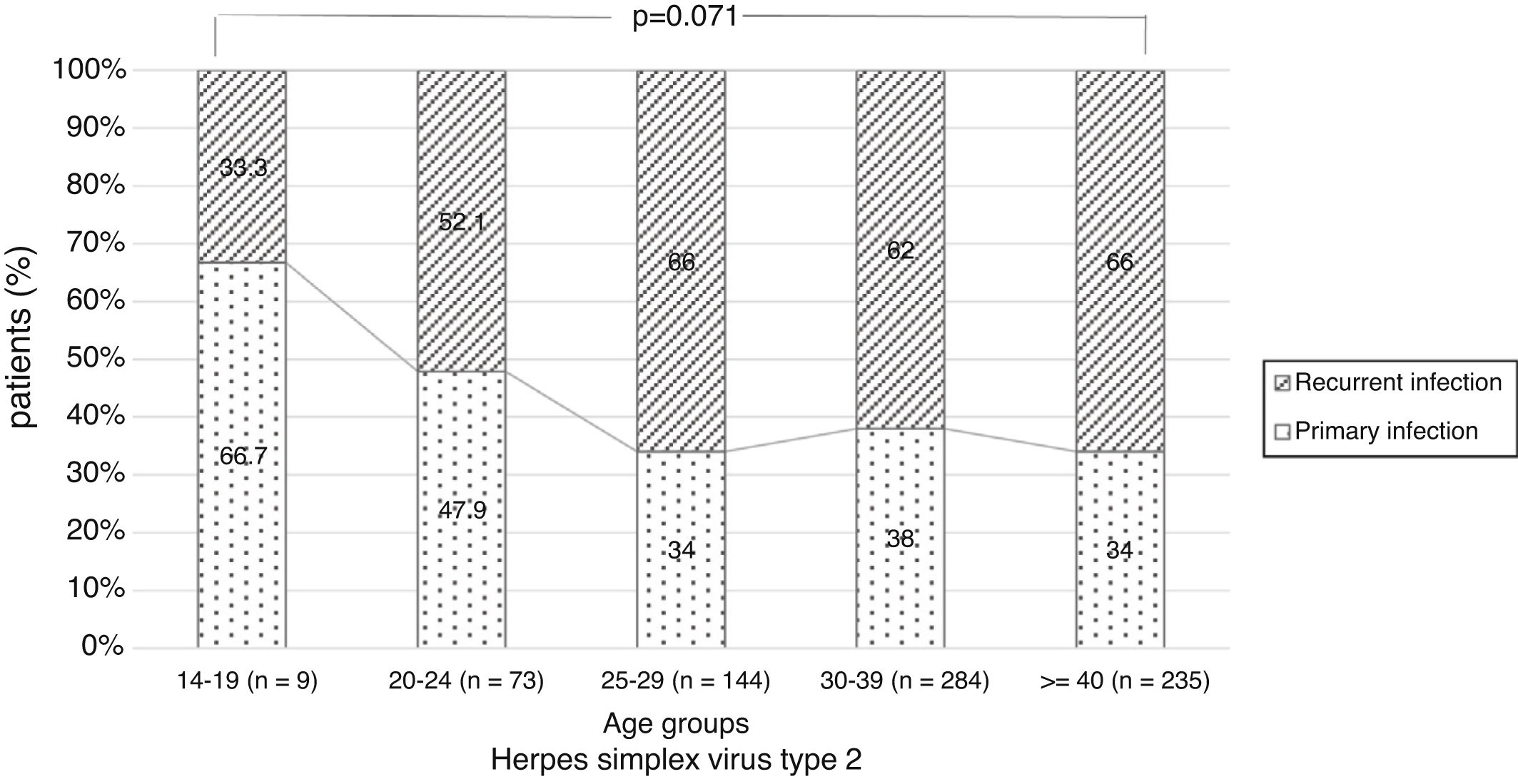

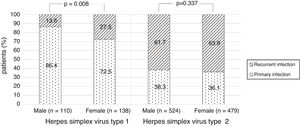

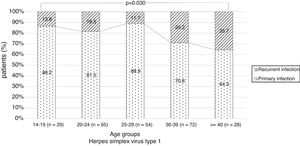

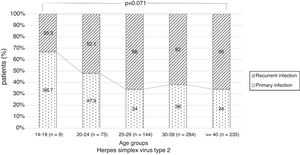

There were no significant differences in the stage of infection according to patients’ gender (p=0.569), but males with genital HSV-1 infection were more frequent with primary infection (86.4%) than females (72.5%) (p=0.008) (Figure 1). Patients under 30 years were diagnosed with primary infection in most of cases (p=0.030) (Figure 2). In case of patients with genital HSV-2 infection older than 25 years more than 60% of them had recurrent GH (p=0.071) (Figure 3).

After the first microbiological diagnosis of GH, 634 patients reported symptomatic recurrence. Only 4.4% of patients with GH due to HSV-1 had two or more recurrences in a year in comparison of 32.5% of patients with genital HSV-2 infection (p<0.0001) (Table 2).

Acyclovir was the most used antiviral (34.4%) in this study for the treatment of GH and the clinical evolution of patients was good in 98.4% of cases (data not shown).

Prior sexually transmitted diseasesThe study showed 488 patients (48.7%) had previous history of STDs. Condyloma acuminatum (12.5%), HIV infection (10.7%), hepatitis B virus (10.7%), syphilis (9.4%), C. trachomatis (8.6%), N. gonorrhoeae (6.9%), T. vaginalis (4%) and hepatitis C virus (3.8%) were more frequent in the group of patients with GH by HSV-2 compared with patients with genital HSV-1 infection (p<0.05) (Table 2). The only previous STD significantly associated with GH by HSV-2 was N. gonorrhoeae infection in the multivariate model (OR: 3.91 [95% CI: 1.20–12.73], p=0.0235) (Table 3).

DiscussionThe incidence of patients diagnosed of GH has increased worldwide1,8,16–18 and HSV-2 is the main agent.4–7 Nevertheless, during the last decades the proportion of HSV-1 as a causative agent of GH has increased in some developed countries. So much so that an analytical modeling in the United States shows that HSV-1 will persist as a major cause of primary GH for decades to come.19 In many countries of Europe and Asia the proportion of genital HSV-1 infection varies by different regions, but the evolution is similar.6,17,18 In Spain, in a recent study conducted in Valencia, 47% of patients had genital HSV-1 infection20 and during our study period, the proportion of that infection increased clearly. The mean age of the patients was similar to other publications6,11 and, overall, the rate of males was higher than females. However, the majority of patients with genital HSV-1 were female and they were younger than patients with genital HSV-2 infection. This is similar to other studies.4,6,11,21 Early sexual debut in adolescents and young adults and oral receptive sex in seronegative females are the main sexual risk of genital HSV-1 infection.24 Moreover, the anatomic and histologic differences of genitals in both genders must be taken into account.22 In our study oral sex was significant sexual practice in patients with genital HSV-1 infection and most of them had previous contact with orolabial herpetic lesions of sexual partner. Therefore, it is essential to remind patients that HSV can transmit by different ways, despite the existence or not of visible herpetic lesions and the importance of using condoms or other barrier methods. If they are used correctly in all types of sexual practices, barrier methods can reduce the risk of most STDs, including GH. Despite these results, in the current study the increase of the proportion of patients with genital HSV-1 infection was higher in males. This result is similar to other Australian publication,4 but in other studies the increase of GH by HSV-1 was observed in females.6 On average, in the study period, Bilbao had a foreign population of 7%.23 So, the significant high rate of foreign patients with GH, specially caused by HSV-2 infection is interesting. This data is similar to worldwide HSV-2 seroprevalence study that observed highest prevalence in Africa followed by the Americas.1

Local and systemic manifestations of GH caused by the two types of HSV are similar and they cannot distinguish one from another. There is some evidence that local and systemic symptoms of primary infection are more severe.3 Female diagnosed with primary infection showed more leucorrhea and cervicitis compared with recurrent infection. These findings could help clinicians to suspect primary genital infection. Nevertheless, these clinical differences could not be evident in some cases.21 Proctitis is also an important physical sign in male with genital HSV-1 infection and is clearly associated with anal sex practice in MSM. Thus, GH should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute proctitis.

HSV-2 has been shown to reactivate more than HSV-15,13,15,20,25 and in this study more than half of patients had recurrent infection, especially in genital HSV-2 infection. Most of patients diagnosed of primary infection caused by HSV-1 were male. This could be explained because the proportion of MSM was high in that group of patients. Lafferty et al. found similar results in relation to MSM with GH.13 Moreover, Nilsen et al. reported that recurrent genital HSV-1 infection was more prevalent in females.25

In this study, we found a significantly higher number of recurrences in patients with genital HSV-2 infection. These results are consistent with other studies where recurrences occur in more than a third people suffering symptomatic primary GH due to HSV-2.26

The common sexual profile of patients with GH in current study was stable sexual partner. Nevertheless, we found differences according to the type of HSV. Activities related to prostitution and parenteral former drug users were more frequent in patients with genital HSV-2 infection but only prostitution was significantly associated with it in the multivariate model. Van de Laar et al. submitted that female sex workers had a higher risk to contracting genital HSV-2 infection.27

We found diverse results related to the number of sexual partner in patients with GH. The high proportion of patients with more than six sexual contacts in last year in patients with genital HSV-2 infection was surely associated with sex workers that were more common in that group. Some seroprevalence studies observed that the population with a high number of sexual partners had more seropositivity rate of HSV-2.14,28 However, Cherpes et al. found that HSV-1 seroprevalence was higher in women with more than five sexual partners in lifetime.24

Finally, in this study we found that a history of previous STDs was more frequent in patients with genital HSV-2 infection and this is clearly demonstrate in some studies.5,20,24,28–30 Anyway, in our study only N. gonorrhoeae infection was significantly associated with GH caused by HSV-2. Gottlieb et al. reported in a seroprevalence study the association between syphilis, C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae and T. vaginalis infections and genital HSV-2 infection.14 In other studies with similar characteristics, previous STDs did not statistically significant in genital HSV-2 infection.11,30

In conclusion, our study is one of few studies conducted on patients with GH microbiologically confirmed by direct methods. Although the current study consists of patients of two clinics in Bilbao, the findings allow clear conclusions in our community. During the study period, the number of GH caused by HSV-1 has increased significantly, especially in males. Despite that, the data collected indicate that patients with genital HSV-1 infection are usually young females, whereas GH by HSV-2 is seen more often in older males. Primary genital infection is more common in patients with genital HSV-1 infection compared with HSV-2 infection. In addition, prior contact with herpetic oral lesions of their partners and oral sex is common in patients with GH caused by HSV-1. MSM are also an important collective among those infected with HSV-1 in anogenital region. History of previous STDs and the sexual profile of prostitution are more frequently related to genital HSV-2 infection.

The authors recognize some limitations in this study. STD medical consultations of Bilbao-Basurto IHO attend patients from areas around town, so they may not be representative of the entire region of Bilbao population. Because the recruitment of patients has been carried out based on microbiological results of samples, there is lack of data of patients with symptoms suggested GH but not confirmed microbiologically. Finally, the subsequent follow-up of some patients has not been strict especially due to lack of interest of patients and the treatment of posterior recurrent infections by the primary care physician.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest