This was the case of a 31-year-old male patient originally from Morocco (he had not travelled there for eight years) who went to the accident and emergency department for a six-month history of cough with limited yellow expectoration and no other associated symptoms. Regarding epidemiological history, the patient reported spending long periods with dogs during his childhood.

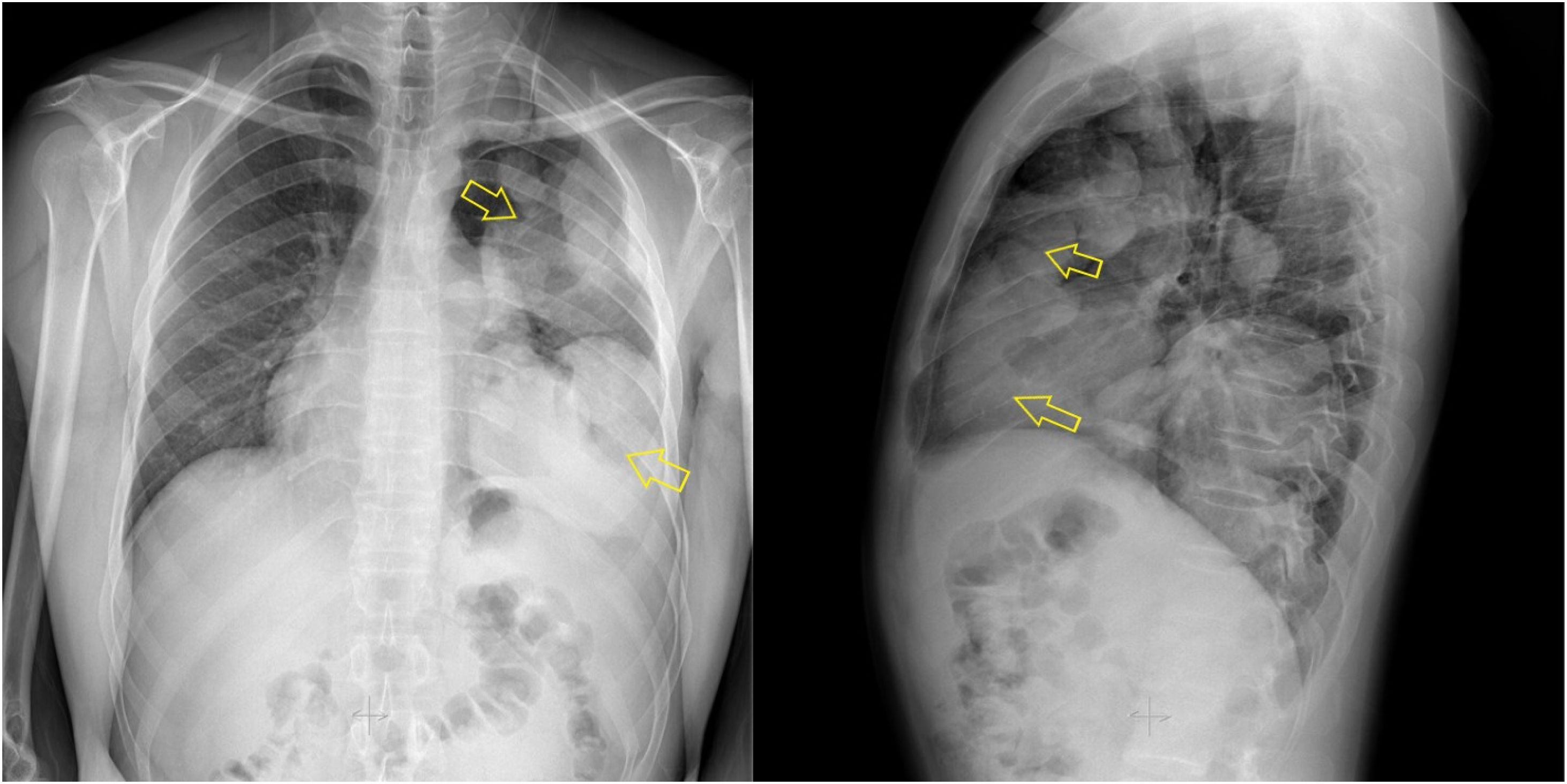

Upon examination, he presented with left pulmonary hypoventilation with hypophonesis in the lung base and a painless left clavicular lump, of one year of evolution. Blood tests revealed CRP of 8.31 mg/l and 760 eosinophils/μl. A chest X-ray (Fig. 1) revealed a mass that occupied practically the entire left lung, and the patient was admitted for study with IV levofloxacin 500 mg/24 h.

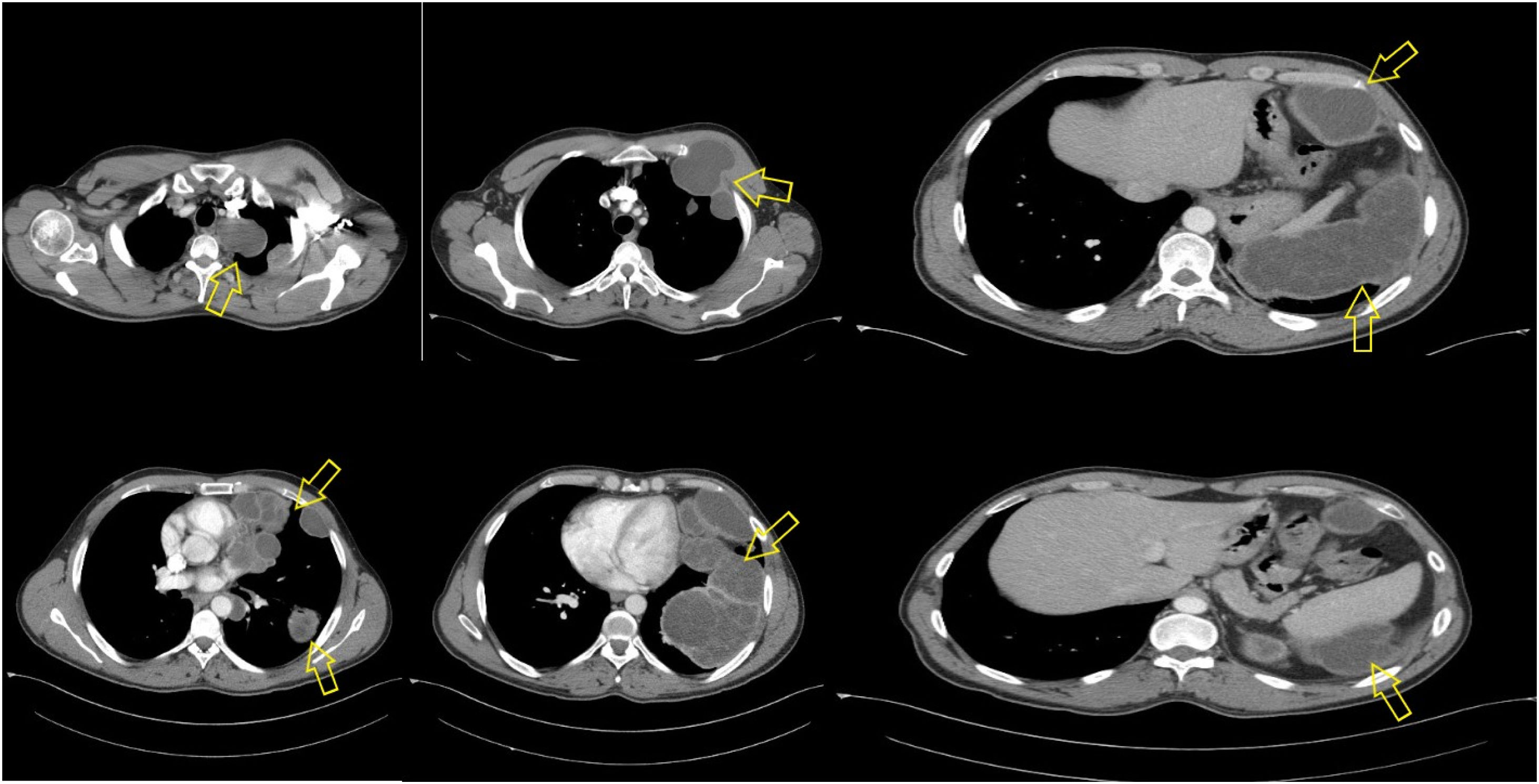

Sputum culture and SARS-CoV-2 PCR were negative, so a computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, whereby large pleural cystic lesions of up to 12 cm and with multiple internal septa were observed (Fig. 2). Other lesions protruded towards the left pectoral between the second and third costal arch, extending from the left lung base to the left hypochondrium and the posterior face of the spleen, consistent with diffuse pleural hydatid disease. A serology sample was obtained for the detection of serum antibodies against Echinococcus granulosus. The Hydatidose FumouzeR (Fumouze Diagnostics, Levallois-Perret, France) test detected serum antibodies at titres 1:1,024, which was confirmed by a second sample.

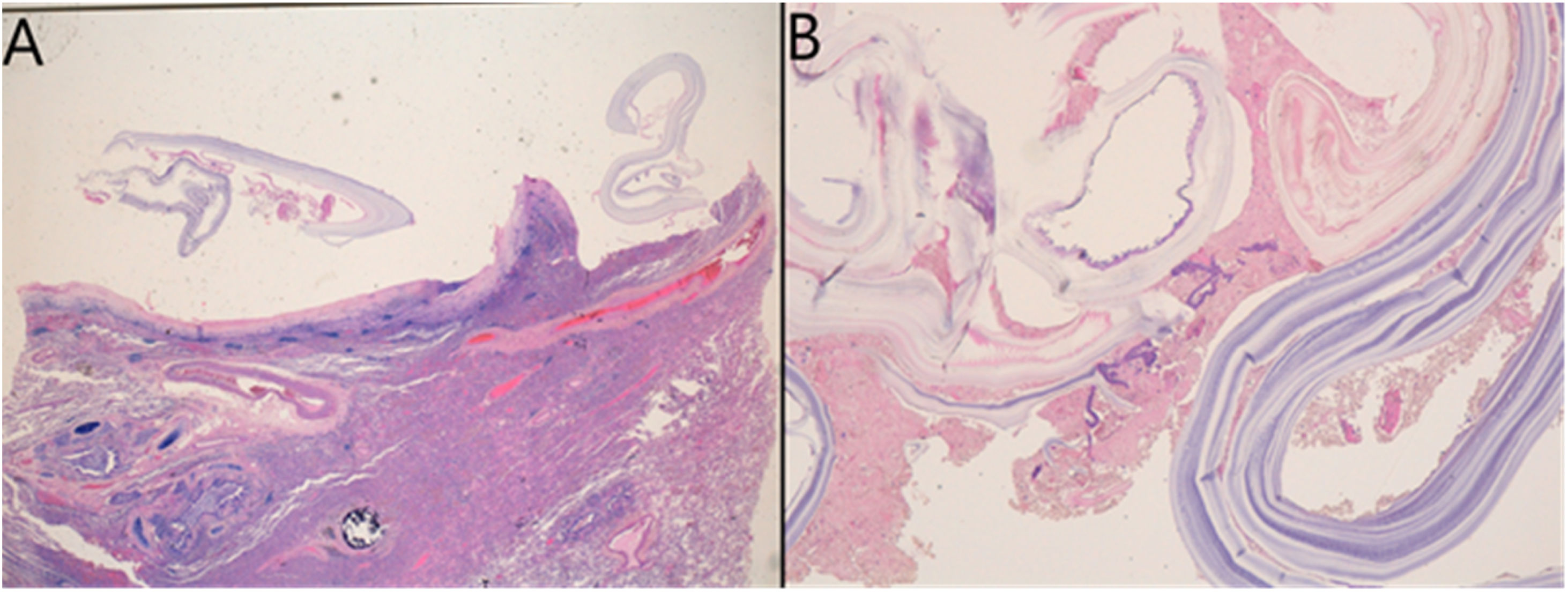

Clinical courseMultiple cystectomy was decided on, and the patient received a 400-mg dose of albendazole four hours prior to surgery. Up to 15 different cysts were resected and sent to Pathology, with cystic formations consisting of a fibrous wall on the periphery with fine concentric laminations and a central germinal layer being observed. The cystic wall caused a peripheral inflammatory reaction with abundant eosinophils and multinucleated foreign-body giant cells (Fig. 3). The patient received 400 mg/12 h of oral albendazole for three months with clinical improvement. Six months later, a CT was performed with only a 35-mm paramediastinal cystic lesion observed, along with another 25-mm lesion in the area of the inferior pulmonary ligament.

Pathology of one of the cysts. (A) Pleuropulmonary tissue, with inflammatory changes and fibrosis in the pleural area corresponding to the adventitial fibrous outer layer of the hydatid cyst. (B) Detailed image (×400) of the layers of the hydatid cyst; on the right is the middle laminated layer (cuticle) and loose disintegrated strips of the innermost layer (germinal).

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) or hydatid disease is a parasitic zoonosis that is caused in humans by the larval stage of three different species of Echinococcus spp., including Echinococcus granulosus, Echinococcus ortleppi and Echinococcus canadensis. The World Health Organization considers it to be one of the 20 neglected tropical diseases; diseases that are almost totally absent from global health programmes causing personal and professional harm to neglected populations. The disease has a global distribution, with higher prevalence in countries in Mediterranean countries, North and East Africa and China, among others. In a recent article, Casulli et al. reported the incidence of cases in many European countries. In Spain, the incidence in the period 1997–2020 was one case per 100,000 inhabitants, while in the period 2017–2019 it was 0.56 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, with a total of 10,675 reported cases and a decreasing trend since 1997.1

It is transmitted within the domestic domain, with dogs participating as definitive hosts, small ruminants as intermediate hosts and humans as accidental hosts. Eggs released by infected dogs remain the most important source of infection. Hydatid disease is usually asymptomatic until a complication occurs, from cyst rupture causing an anaphylactic reaction, to development of a fistula or mass effect on surrounding structures, and it is frequently an incidental finding. Most patients present with a single cystic lesion located in a single organ, most typically the liver (in up to 70% of cases). Oncospheres can sometimes bypass the hepatic circulation system and gain access to the systemic circulation system, from which they can spread to other organs such as the lung (most common extrahepatic area of involvement), abdominal or pleural cavities, kidney, brain or the eye.2 However, isolated lung involvement is uncommon in hydatid disease.

The diagnosis is fundamentally based on clinical findings, epidemiological history, serology and imaging studies. Definitive diagnosis is reached by finding the parasite in the microscopic examination of the hydatid cyst fluid or in the histological sample.

In Spain, the number of cases of CE, both autochthonous and imported, seem to be underdiagnosed for two reasons: (a) diagnostic tests (ultrasound/CT and serology) are only performed in symptomatic patients; and (b) reporting of cases to the epidemiological surveillance systems is suboptimal. In fact, the review by Zabala et al. highlights the deficiency of the current Spanish and European reporting systems due to the disparity of cases reported in the literature compared to those declared.3

On another note, treatment is based on three important points: use of antiparasitics, surgery or percutaneous drainage (PAIR), although the latter is contraindicated in cases of pulmonary hydatid disease, which requires taking a surgical approach using thoracotomy. In symptomatic patients with cysts smaller than 5 cm or that are inoperable, benzimidazoles can be used as the only treatment, generally in the form of albendazole 400 mg twice a day for six months, as well as alongside surgery or PAIR to prevent secondary echinococcosis (or hydatid seeding). In the case of asymptomatic carriers, the “watch-and-wait” therapeutic approach may be used in heterogeneous or calcified cysts (CE4, CE5 or even inactivated CE3b from the classification of cysts by ultrasound diagnosis). Treatment with albendazole prior to or after surgery is mandatory in many cases given the high risk of secondary seeding after cystectomy. Depending on the clinical situation and the number or size of the cysts, the most appropriate type of treatment will be selected jointly.4 Follow-up of the cases should be carried out every six months during the first two years with imaging and serological tests. However, there is no clear unification of criteria and there are discrepancies in clinical practice (in our case serological follow-up was not performed).

Informed consentConsent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the case.

FundingNo funding was received for the drafting of this scientific letter.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.