A 51-year-old patient, a moderate alcohol consumer with a history of bimalleolar fracture of the right ankle nine years earlier, for which he required open reduction and osteosynthesis with a fibular plate and screw in the medial malleolus, was admitted due to ascitic decompensation in the context of Child C liver cirrhosis for control and study. At admission, the patient presented oedema and erythema in the right lower extremity, with a painful subcutaneous abscess on palpation. Surgical debridement was performed, with abundant purulent exudate discharge and osteosynthesis material was extracted, sending samples for cultures.

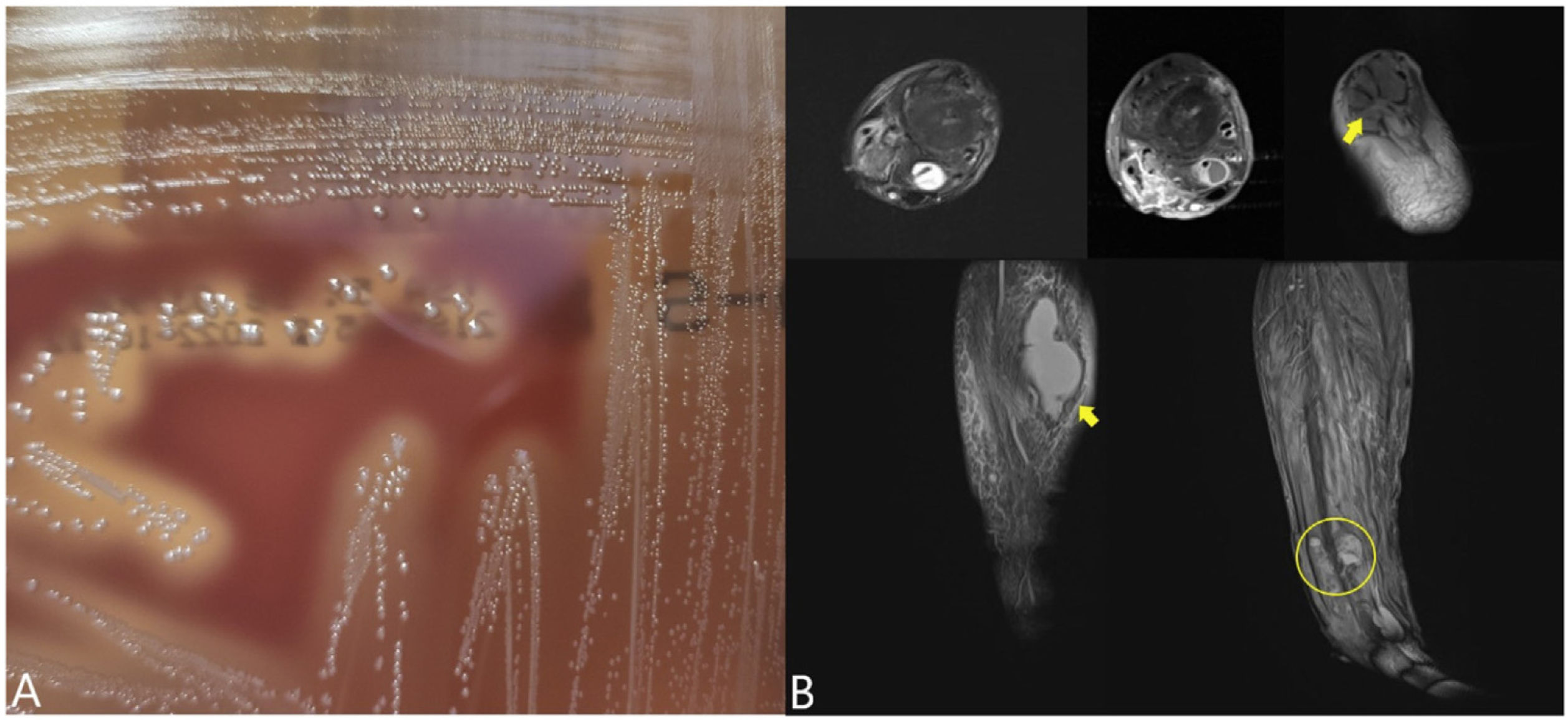

The osteosynthesis material sample was introduced into a container with thioglycolate enrichment medium, which was incubated at 37°C in aerobic conditions for 24h and subsequently Gram stained, and inoculated on chocolate and Brucella agars. Abscess samples were plated on chocolate, TSA with 5% sheep blood, McConkey, CNA and Brucella agars. In all the Gram stains, gram-positive cocci were identified in chains and pairs. At 24hours, β-haemolytic colonies grew on the TSA agars (Fig. 1A), identified as Streptococcus canis (S. canis) using a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker, Massachusetts, United States) with a value of 2.15. Antibiotic susceptibility was studied using the SMIC-ID-11 panel on the BD Phoenix™ (Becton Dickinson, New Jersey, USA) AP system. The strain was sensitive to penicillin (MIC ≤0.03mg/l), erythromycin (MIC=0.125mg/l), clindamycin (MIC=0.06mg/l), tetracyclines (MIC ≤0.5mg/l), vancomycin (MIC ≤0.5mg/l), teicoplanin (MIC ≤1mg/l) and daptomycin (MIC ≤0.25mg/l), while it showed increased dose sensitivity for levofloxacin (MIC=1mg/l) (EUCAST criteria; www.eucast.org).

A) β-haemolytic colonies on TSA agar with 5% sheep blood (24h incubation, 5% CO2). B) Collection in the posterior aspect of the leg (diameters of 8×5×2cm) compatible with abscess (lower arrow), pretibial collection (1.7cm) in the middle third and other collections at the distal level (circle). Collection in the region of the joint in relation to the tendon and flexor sheath of the big toe of 2cm (upper arrow). Signs of renal alteration were also observed in relation to osteitis or incipient osteomyelitis in the external malleolus, in relation to the course of the screws removed along 10cm and with diffusion coefficient restriction, in both cases abscessed.

The patient began receiving IV antibiotic treatment with ceftriaxone (2g/24h) and improved substantially, although after four days he developed oedema and erythema on the back of the right leg. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed collections along the leg (Fig. 1B) that were drained and six samples were cultured. In the Gram stain of two samples Gram-positive cocci were observed in pairs, although there was no growth. The patient denied having contact with animals in recent years.

After 21 days, he was reassessed and, given his good clinical progress and test results, he was discharged with outpatient follow-up. He received two more weeks of treatment with oral amoxicillin (500mg/8h), completing a total of six weeks, with good progress and no complications.

DiscussionS. canis is a β-haemolytic streptococcus belonging to Lancefield's group G, which is part of the microbiota of the skin and mucous membranes of many animal species (especially dogs and cats) and its main virulence factors are the arginine-deiminase system and the M protein.1-3 While the arginine-deiminase system would favour bacterial growth, the M surface protein increases bacterial survival by recruiting plasminogen and binding IgG-Fc to the bacterial surface (preventing opsonisation by C1q).

Direct contact with domestic animals through bites, with their fluids (such as saliva or urine), or prolonged contact with their fur or skin would explain the origin of some human infections caused by S. canis. However, in many cases the cause is unknown.4 In fact, in one series only one patient out of a total of 54 reported close contact with domestic animals.5

Most human infections are of the skin and soft tissue and proceed without complications, although in other cases, it can lead to serious infections such as sepsis or endocarditis.5,6 This microorganism has also been reported as a cause of periprosthetic infection in a total of three patients to date, and in two of them a history of close contact with animals was described.5,7,8 In prosthetic infections, the usual treatment consists of antibiotics for 4-6 weeks, open irrigation and debridement with possible surgery to explant the osteosynthesis material. Despite this, in some cases it seems that a conservative approach with minimal debridement, antibiotics and retention of the implant could be just as effective.9 However, it also seems that in other series, there is a high failure rate despite adequate focus control and antibiotic treatment, which opens the way for investigation of other possible treatments such as the concomitant use of bacteriophages.10 In our case, despite the first debridement with explant surgery, the patient required a second surgical intervention, demonstrating the importance of close follow-up and focus control in these infections.

FundingNo funding was received.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.