In infants under 3 months of age, fever may be the main symptom or the only manifestation of a potentially serious disease, so differentiating between an invasive bacterial infection and other processes continues to be a diagnostic challenge. In recent years, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) molecular techniques have made it possible to carry out early and reliable aetiological diagnosis of some germs, especially viruses, modifying some aspects of hospital management.1 Enteroviruses have become more important in recent years and during the epidemic period can account for up to 65% of paediatric hospitalisations with febrile syndrome.2

We present a prospective observational series of 39 infants under three months of age (16 neonates) with enterovirus meningoencephalitis diagnosed by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) PCR admitted to a tertiary referral hospital over a period of four years (September 2012-September 2016). The specific real-time PCR technique was used (MutaREX® Enterovirus rt-PCR Kit, Immundiagnostik AG, Germany). Three patients with concomitant bacterial infection were excluded; all had Escherichia coli urinary tract infections.

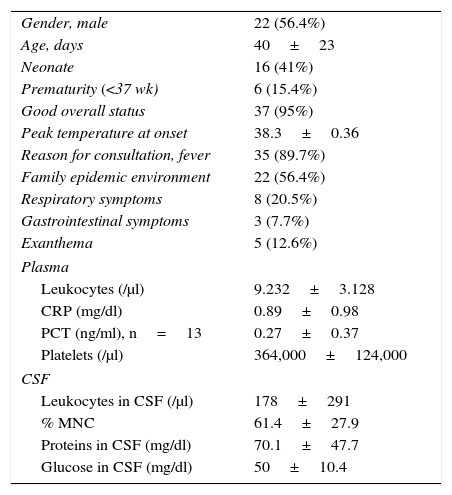

The main clinical and analytical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The most common reason for consultation was isolated fever (89.7%), with 95% being generally well. In the CSF, the leucocyte count ranged from 2 to 1263 cells/μl (median 36 cells/μl), predominantly mononuclear cells. Pleocytosis was found in 64% of patients. The mean hospital stay was 4.8±4 days (median 4). Empirical antibiotic therapy was given to 79.5%, with mean treatment duration of 4.2±5.7 days (median 3), and this was discontinued in 50% of the patients the same day the PCR results were obtained. Clinical outcome was favourable in all cases, except for one patient who required intensive care for sepsis-like syndrome (hepatic failure, coagulopathy, thrombocytopaenia) caused by Echovirus 11. Nasopharyngeal aspirates were requested in 26 patients for viral analysis, and enterovirus was isolated in 73% of the samples.

Clinical and analytical characteristics of infants aged <3 months with enteroviral meningoencephalitis.

| Gender, male | 22 (56.4%) |

| Age, days | 40±23 |

| Neonate | 16 (41%) |

| Prematurity (<37 wk) | 6 (15.4%) |

| Good overall status | 37 (95%) |

| Peak temperature at onset | 38.3±0.36 |

| Reason for consultation, fever | 35 (89.7%) |

| Family epidemic environment | 22 (56.4%) |

| Respiratory symptoms | 8 (20.5%) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 3 (7.7%) |

| Exanthema | 5 (12.6%) |

| Plasma | |

| Leukocytes (/μl) | 9.232±3.128 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.89±0.98 |

| PCT (ng/ml), n=13 | 0.27±0.37 |

| Platelets (/μl) | 364,000±124,000 |

| CSF | |

| Leukocytes in CSF (/μl) | 178±291 |

| % MNC | 61.4±27.9 |

| Proteins in CSF (mg/dl) | 70.1±47.7 |

| Glucose in CSF (mg/dl) | 50±10.4 |

CRP: C-reactive protein; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; MNC: mononuclear cells; PCT: procalcitonin.

Quantitative variables expressed as the mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables expressed as “n” and percentage of the total sample.

No statistically significant results were obtained when comparing neonatal patients (<28 days) with the rest of the sample, except for less development of exanthema in the neonates group (21.7% vs 0%, p=0.046).

The incorporation of molecular techniques into clinical practice has allowed many conditions previously classified as fever without a source or aseptic meningitis to be identified as enteroviral infections. It has previously been shown that CSF enterovirus PCR testing is associated with a reduction in number of days in hospital and the use of antibiotics.1 In our series, empirical antibiotic therapy was discontinued the same day the PCR was obtained in 50% of the cases, clearly demonstrating the potential benefits in terms of healthcare and financial costs.

In our sample, the patients did not have significant analytical abnormalities in blood and we confirmed that CSF pleocytosis is not a reliable marker of enterovirus infection in young children; this could be related to a weaker inflammatory response in infants to enterovirus infection.3,4

The positive nasopharyngeal aspirate cultures (73% in our series), not being decisive in therapeutic management during admission, indicate that the study of enterovirus in other organic fluids could be useful in the diagnosis of children with aseptic meningitis. Foray et al. compared the combined use of pharyngeal aspirate and CSF to improve detection of enterovirus in children with aseptic meningitis, detecting enterovirus in 75% of cases compared to 32% when they only analysed the CSF.5 Another study during an outbreak of enterovirus-71 encephalitis in children found that it is not always detected in CSF, requiring the study of enterovirus in nasopharyngeal aspirate and/or faeces. Among the possible explanations are the lower viral load in CSF or the transient nature of enterovirus in the CSF.6

In conclusion, enteroviral meningitis is usually benign, even in young infants. We believe that the determination of enterovirus in CSF is advisable in the study of all febrile infants aged less than 3 months in whom lumbar puncture is performed, even if they do not have pleocytosis. The use of molecular techniques could potentially contribute to reducing the number of days of unnecessary antibiotic therapy.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Seoane Rodríguez M, Cañizares Castellanos A, Avila-Alvarez A. Meningitis por enterovirus en niños menores de 3 meses. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:680–681.