Recently, Kingella kingae (K. kingae) has been described as the most common agent of skeletal system infections in children 6 months-2 years of age. More exceptional is the clinical presentation in clusters of invasive K. kingae infections. We describe the investigation of the first outbreak of 3 cases of arthritis caused by K. kingae documented in Spain detected in a daycare center in Roses, Girona.

Patients and methodsIn December of 2015 surveillance throat swabs obtained from all attendees from the same class of the index daycare center were assessed to study the prevalence of K. kingae colonization. The sample was composed of 9 toddlers (range: 16–23 months of age). Investigation was performed by culture and K. kingae-specific RT-PCR. Combined amoxicillin-rifampicin prophylaxis was offered to all attendees who were colonized by K. kingae. Following antimicrobial prophylaxis, a new throat swab was taken to confirm bacterial eradication.

ResultsK. kingae was detected by RT-PCR throat swabs in the 3 index cases and 5 of the 6 daycare attendees. Cultures were negative in all cases. After administration of prophylactic antibiotics, 3 toddlers were still positive for K. kingae-specific RT-PCR.

ConclusionsClusters of invasive K. kingae infections can occur in daycare facilities and closed communities. Increased awareness and use of sensitive detection methods are needed to identify and adequately investigate outbreaks of K. kingae disease. In our experience, the administration of prophylactic antibiotics could result in partial eradication of colonization. No further cases of disease were detected after prophylaxis.

Recientemente, Kingella kingae (K. kingae) se ha descrito como el principal agente causal de infecciones osteoarticulares entre los 6 meses y 2 años de vida. Más excepcional es su presentación en forma de clúster de infección invasiva por K. kingae. Se describe la investigación del primer brote de 3 casos de artritis séptica causada por K. kingae documentado en España en una guardería de Roses, Girona.

Pacientes y métodosEn diciembre del 2015, se realizó frotis faríngeo a todos los niños de la misma clase de la guardería. La muestra estaba compuesta por 9 lactantes (rango de edad: 16–23 meses), que incluía los 3 casos índice. El estudio microbiológico se realizó mediante cultivo y RT-PCR específicos a K. kingae. Se administró amoxicilina y rifampicina profilácticas a todos los que presentaron colonización por K. kingae. Después de finalizar la profilaxis, se tomó un nuevo frotis faríngeo para confirmar la erradicación.

ResultadosSe detectó K. kingae por RT-PCR en los 3 casos índices y 5/6 compañeros de clase. Los cultivos fueron negativos en todos los casos. Después de recibir profilaxis, 3 lactantes aún presentaban positividad a K. kingae en RT-PCR.

ConclusionesK. kingae puede causar brotes de enfermedad invasiva en comunidades cerradas. Para una adecuada investigación, se requiere un mayor conocimiento de su existencia, así como una mejoría de la sensibilidad de las pruebas diagnósticas. En nuestra experiencia, la administración de profilaxis antibiótica puede erradicar parcialmente la colonización orofaríngea por K. kingae. Después de la profilaxis no se detectaron nuevos casos.

Until the 1990s, Kingella kingae (K. kingae) was considered an exceptional human pathogen as a rare aetiologic agent of osteoarticular infections and endocarditis. In recent years, thanks to improved microbiological diagnostic techniques and greater awareness in recognising it K. kingae is being more frequently identified as a cause of invasive disease (ID) in children.1,2 In fact, K. kingae is currently considered to be the first causal agent of osteoarticular infections in children under four years of age.3–5

K. kingae is part of the commensal flora of the oropharynx. Colonisation represents the first step in the pathogenesis of the ID and is closely related to age, being detected mainly in children between six and 48 months old. It demonstrates a seasonal pattern, being more frequent in winter and early spring.3,6,7

Although most cases of ID due to K. kingae are sporadic, in the last two decades outbreaks have been detected in nursery schools in France, Israel, the United States and Luxembourg.8

We describe the investigation of the first documented outbreak in Spain of three cases of ID caused by K. kingae in the form of septic arthritis (SA) in the same class at a nursery school in Roses, Girona.

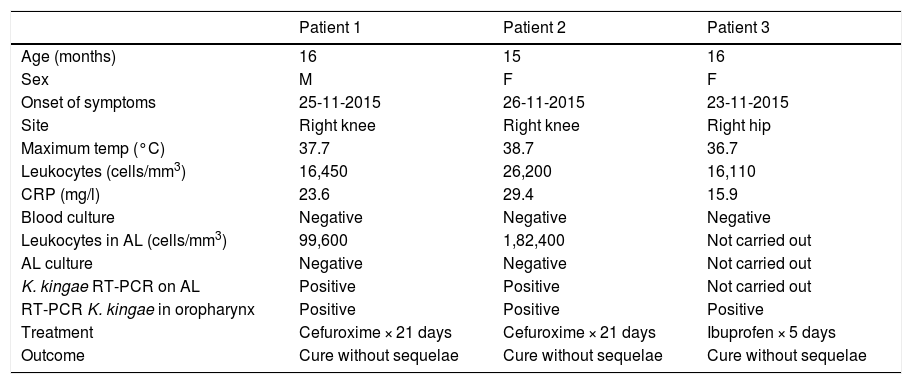

MethodsBetween 23 and 26 November 2015, two cases of SA due to K. kingae were diagnosed in two infants belonging to the same class in a nursery in Rosas, Girona. In both cases, the diagnosis was made by positive RT-PCR on joint fluid. Subsequently, a third probable case of SA due to K. kingae (compatible clinical signs and isolation by RT-PCR specific for K. kingae on oropharyngeal swab) appeared in an infant in the same class. Two of the three cases had a history of an upper respiratory infection in the days before the onset of the clinical signs. The main demographic and clinical characteristics of the three patients are summarised in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with septic arthritis caused by K. kingae.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 16 | 15 | 16 |

| Sex | M | F | F |

| Onset of symptoms | 25-11-2015 | 26-11-2015 | 23-11-2015 |

| Site | Right knee | Right knee | Right hip |

| Maximum temp (°C) | 37.7 | 38.7 | 36.7 |

| Leukocytes (cells/mm3) | 16,450 | 26,200 | 16,110 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 23.6 | 29.4 | 15.9 |

| Blood culture | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Leukocytes in AL (cells/mm3) | 99,600 | 1,82,400 | Not carried out |

| AL culture | Negative | Negative | Not carried out |

| K. kingae RT-PCR on AL | Positive | Positive | Not carried out |

| RT-PCR K. kingae in oropharynx | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Treatment | Cefuroxime × 21 days | Cefuroxime × 21 days | Ibuprofen × 5 days |

| Outcome | Cure without sequelae | Cure without sequelae | Cure without sequelae |

F: female; M: male; RT-PCR: reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Following the appearance of epidemiologically connected cases, it was decided to investigate the prevalence of nasopharyngeal colonisation by K. kingae in the nine children attending the same nursery class. The only exclusion criterion was having received antibiotics in the two weeks prior to the start of the study. Verbal consent was obtained from the parents for their child to participate in the study, which was recorded in the patient’s medical record.

In December 2015, a clinical interview and pharyngeal swab (PS) sampling was conducted in all the children attending the same nursery class. The samples were sent for study to the Microbiology Laboratory of the Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebrón. The presence of K. kingae in PS was investigated by culture, using non-selective and selective media for this microorganism, and by K. kingae-specific RT-PCR. The clonality of K. kingae was studied by multilocus sequence typing and sequencing of the gene that encodes the RtxA toxin.

Once the result was obtained, combined prophylaxis with amoxicillin (80 mg/kg/day) and rifampicin (20 mg/kg/day) was offered for two days to all children who presented oropharyngeal colonisation by K. kingae (positive culture or RT-PCR). Fourteen days after finishing secondary chemoprophylaxis (SC), new PS samples were taken from those colonised to confirm bacterial eradication.

ResultsAll the children studied were between 16 and 23 months old, with a predominance of males (6/9). K. kingae was detected by RT-PCR in PS of 8/9 children studied (colonisation rate: 88.9%; attack rate: 33.3%). Among the colonised children, there were three SA index cases and five healthy classmates. All cultures were negative.

The index cases on antibiotic treatment did not receive SC. Both the child with negative RT-PCR and the only child whose parents did not want them to participate were excluded from the study.

SC was well tolerated, with no adverse effects. At 14 days after completion, 2/4 contacts and 1/3 index cases still had positive RT-PCR for K. kingae. All cultures were again negative. The decolonisation rate was 57%.

The clonality study showed that all the contacts and cases were genetically identical, specifically they belonged to clone ST-25 and presented allele 1 of the rtxA gene.

There were no new cases of ID due to K. kingae in the nursery class during the subsequent year of follow-up.

DiscussionThe first documented outbreak of SA due to K. kingae in a nursery school in Spain had a satisfactory outcome, with a high rate of oropharyngeal colonisation among children attending the same nursery class, as has been described.8,9

The global prevalence of oropharyngeal colonisation in two-year-olds is around 9%, with a prevalence of up to 35% among nursery attendees.9 Various factors are involved in the colonisation and spread of K. kingae in a closed community: factors related to the organism (virulence), host and immune factors, and factors related to the environment (previous viral infection, ventilation, number of attendees, degree of overcrowding, daily time in the nursery school, time of year and age of attendees). Age seems to be the fundamental factor that determines the colonisation of the oropharynx.9,10

In the last 16 years, 22 confirmed outbreaks of ID due to K. kingae in nursery schools in France, Israel, the US and Luxembourg have been reported in the literature. A total of 59 cases were recorded, 45% of which were confirmed by isolation of the microorganism in culture or PCR of a sterile sample.8,9,11 Most of the cases presented in the form of osteoarticular infection (SA or osteomyelitis) of a single location (62/70). With treatment, the outcome was favourable in most cases.11

After our outbreak, another outbreak was recorded in Madrid in November 2016 of two cases of RA, on which the data has not been published.11,12

In our outbreak, 2/3 cases had a history of previous respiratory infection, which facilitates disruption of the mucosal barrier of the oropharynx and makes it easier for K. kingae to pass into the bloodstream, with a special tropism for osteoarticular tissue.10

The clonality study showed that clone ST-25, which had allele 1 of the rtxA gene, was responsible for the outbreak and its spread in our nursery school. Four clones of K. kingae with intercontinental distribution (ST-6, ST-14, ST-23 and ST-25) were the cause of most of the outbreaks documented worldwide and showed the same genomic profile.9,11,13

In our outbreak, SC with rifampicin and amoxicillin was well tolerated and demonstrated partial eradication at 14 days, similar to that reported in previous studies.8,14–16 Consequently, its indication continues to be controversial. In contrast, after the administration of SC, no new cases were detected in all the outbreaks to date.8–11.

Our study had some limitations. The non-performance of therapy directly observed in SC and the difficulty of obtaining growth of K. kingae in the pharyngeal swab, limiting the differentiation between colonisation and detection of genetic material of non-viable bacteria in the oropharynx, could compromise the results obtained in the subsequent eradication of the bacteria from the oropharynx.

Although it was not the objective of our study, we also consider that the evaluation of the intrafamily transmission of K. kingae, particularly between siblings aged between 6 and 48 months, could be interesting to better understand the kinetics of oropharyngeal colonisation by said microorganism in another key environment at that age.

In conclusion, K. kingae can cause ID outbreaks in closed communities. For its correct identification and investigation, a high diagnostic suspicion and the use of sensitive methods, mainly molecular methods, are required. In our experience, the administration of SC could result in the partial eradication of oropharyngeal colonisation by K. kingae. No new cases of ID due to K. kingae were detected in the subsequent year of follow-up.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Guarch-Ibáñez B, Cabacas A, González-López JJ, García-González MM, Mora C, Villalobos P. Primer brote documentado de artritis séptica por Kingella kingae en una guardería de España. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:187–189.