Legionella is a well known but infrequent cause of bacterial endocarditis.

MethodsWe report a case of endocarditis caused by Legionella spp. We reviewed previously reported cases in PubMed, Google Scholar and in references included in previous reports, and summarized relevant clinical data.

ResultsA 63-year-old man with a history of aortic valve replacement developed persistent fever and monoarthritis. Transesophageal echocardiography showed perivalvular abscess. He died during surgery. Blood and valve cultures were negative. Legionella spp. was demonstrated with 16S-rRNA PCR from the resected material. Twenty cases of Legionella endocarditis have been reported. Harboring a prosthetic valve was the main risk factor. Prognosis was favorable, both for patients treated with or without surgical valve replacement. Overall mortality was <10%.

ConclusionsLegionella is an infrequent cause of endocarditis. It frequently requires surgical treatment. Prognosis is good. Molecular techniques are likely to become the gold standard for diagnosis.

Legionella es una causa bien conocida, aunque infrecuente, de endocarditis bacteriana.

MétodosA continuación, presentamos un caso de endocarditis por Legionella spp. Hemos revisado los casos publicados hasta la fecha en PubMed, Google Scholar y otras referencias incluidas en las comunicaciones previas, y resumimos aquí los datos clínicos relevantes. Un varón de 63 años con historia de recambio valvular aórtico desarrolló fiebre y monoartritis por lo que se realizó un ecocardiograma transesofágico que demostró un absceso perivalvular. Se decidió tratamiento quirúrgico, y el paciente falleció durante la cirugía. Los cultivos tanto de sangre como valvulares fueron negativos. El análisis mediante 16S rRNA PCR del material valvular resecado durante la cirugía demostró Legionella spp. Se han publicado un total de veinte casos de endocarditis por Legionella en la literatura médica. El principal factor de riesgo observado fue la presencia de una válvula protésica. El pronóstico fue bueno tanto para los pacientes tratados de manera conservadora como para aquellos sometidos a recambio valvular quirúrgico. La mortalidad global fue <10%.

ConclusionesLegionella es una causa infrecuente de endocarditis. Generalmente requiere tratamiento quirúrgico. El pronóstico es bueno. Las técnicas moleculares podrían convertirse en el método de referencia para su diagnóstico.

Several species of the genus Legionella have been identified, albeit infrequently, as the causative agents of well documented cases of bacterial endocarditis. The real incidence of Legionella endocarditis is uncertain, as standard blood (and tissue) culture media do not support the growth of these microorganisms. In the last decade, an increase in the number of cases can be observed. This is probably due to the increased diagnostic yield provided by the introduction of molecular techniques. In our report, we outline a novel case of Legionella endocarditis and review previous reports, which provide notable conclusions as experience begins to accumulate with respect to the recognition and management of this disease.

Case reportA 63-year old man, with a past medical history of biological aortic valve replacement in 2015 due to aortic valve stenosis, was first admitted to the hospital in July 2019 with a fever that lasted over 96h. The results of clinical examination and tests (chest radiography, transthoracic echocardiography, cultures, and urine analysis) revealed only mild neutropenia. An infectious agent or focus was not identified. He was diagnosed of presumptive viral infection and was discharged.

The patient continued to experience intermittent fevers; additionally, ten weeks after his discharge, he developed monoarthritis of the first metacarpophalangeal joint. Consequently, the patient was readmitted to the hospital.

Physical examination confirmed monoarthritis and also revealed palpable purpura. He had leukocytosis and a PCR value of 4.5mg/dl. Serial blood cultures were negative, as well as serologic tests for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella henselae, Brucella sp., Borrelia burgdorferi and Leptospira sp. Serological testing for Legionella sp. was not performed.

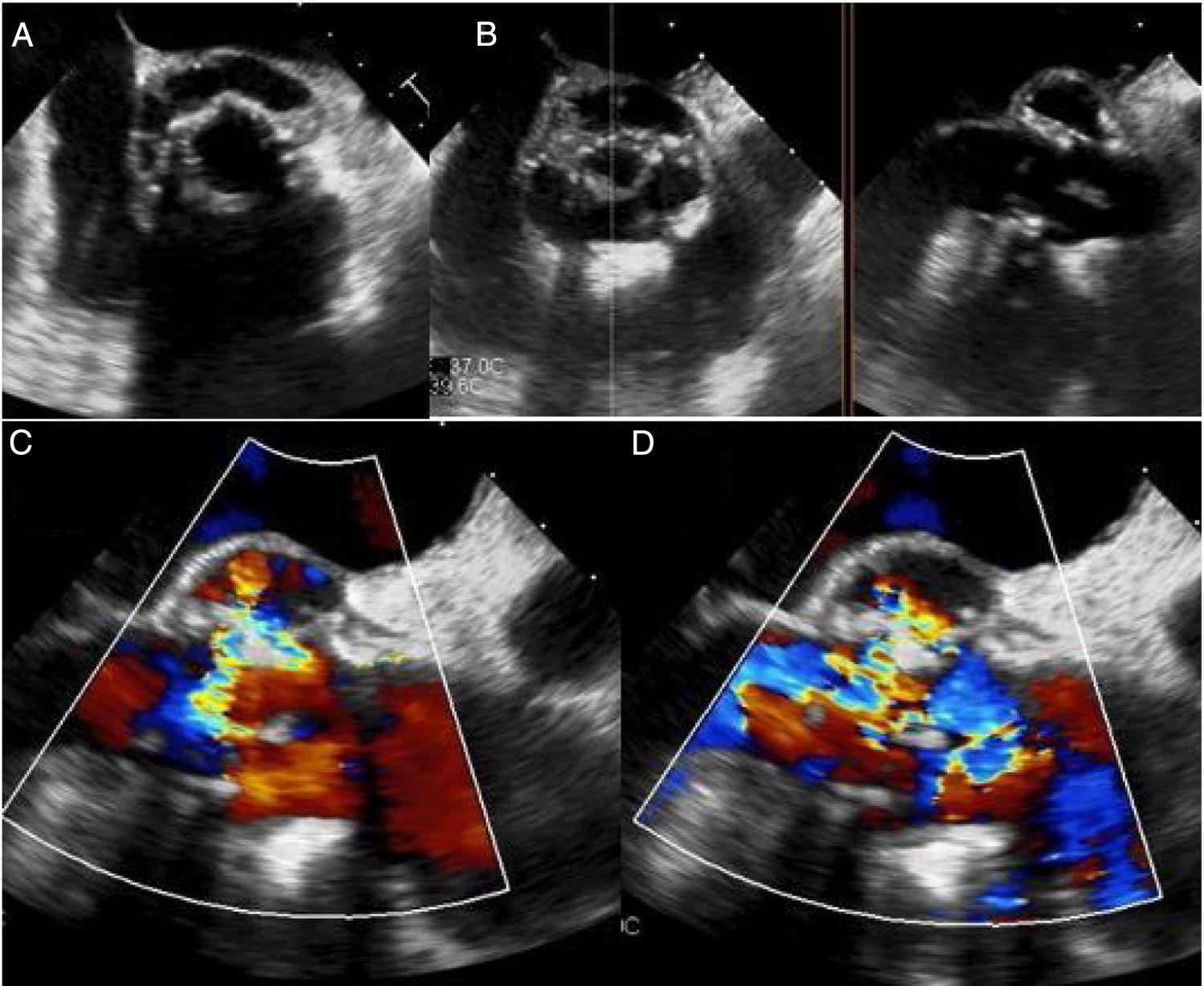

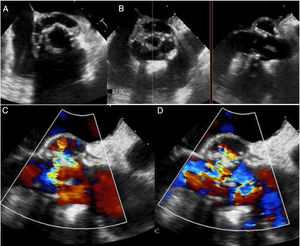

A transesophageal echocardiogram was performed which showed vegetation in the aortic prosthesis and a large periprosthetic abscess (180° around the prosthesis). The abscess led to the formation of a fistula from the ventricular outflow tract to the ascending aorta. The mitral valve was free of vegetation; however, the abscess reached the mitro-aortic curtain (Fig. 1).

(A) Transesophageal echocardiography (longitudinal plane) showing a circumferential abcess 180° around the aortic prosthesis; (B) X plane imaging with transesophageal echocardiography showing the periprosthetic abscess. (C and D) Transesophageal echocardiography (horizontal plane) showing fistula from the ventricular outflow tract to the ascending aorta on a color Doppler map.

The patient was submitted for aortic root replacement and left coronary button re-implantation. He died during the procedure due to hemorrhagic and cardiogenic shock. Culture of the resected material was negative; however, 16S rRNA polymerase chain reaction was positive for Legionella spp.

DiscussionEpidemiologyValvular Legionella infection was first described in 1984 in a 60-year-old woman with a mitral prosthetic valve. Legionella organisms are considered to cause lesser than 1% of all types of bacterial cardiac infections.2

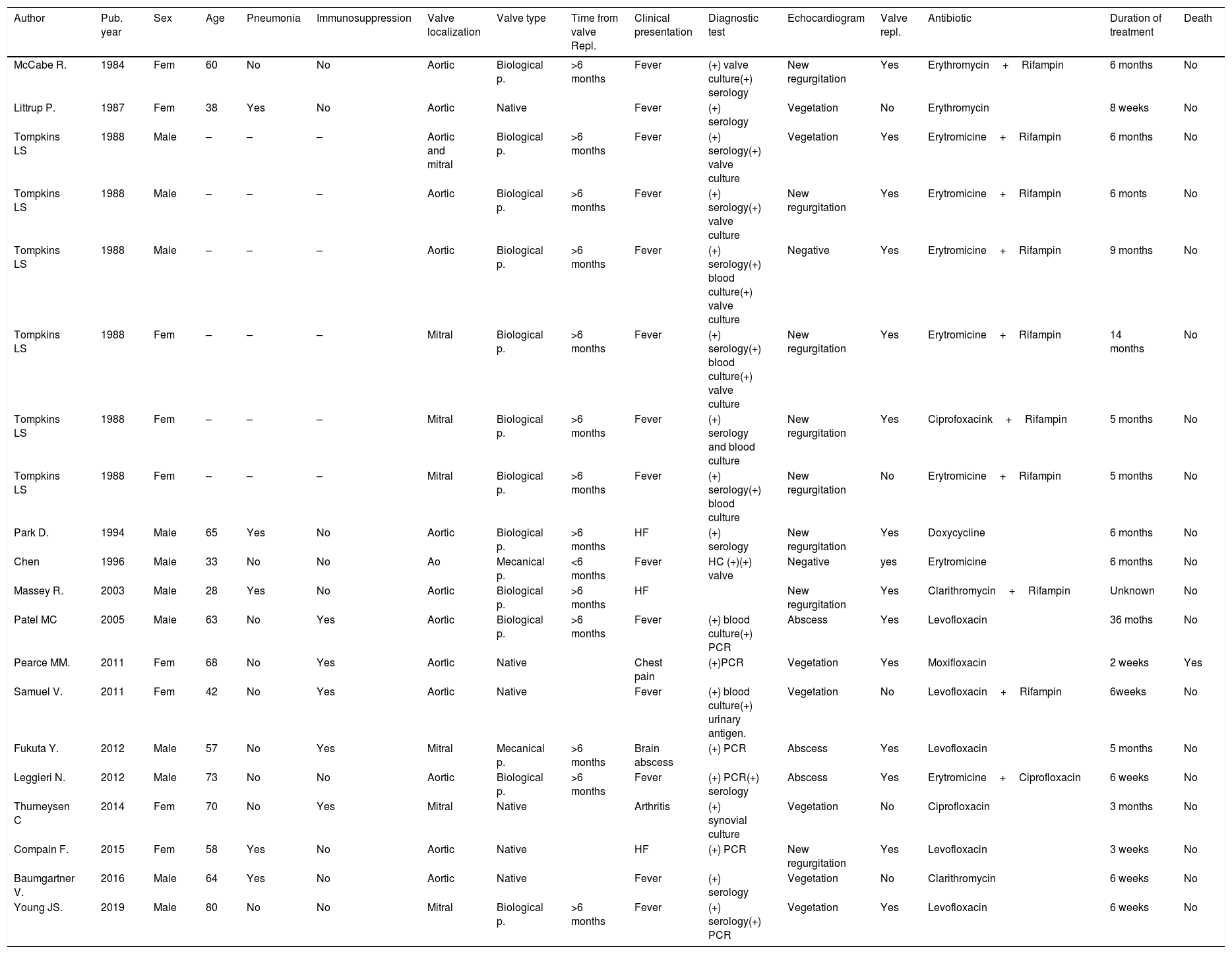

We have reviewed 20 cases (11 men (55%) and 9 women (45%)); median age: 58.9 years old (range 28–80 years) of Legionella endocarditis reported in the medical literature.1-15. The data on gender, age, clinical features, diagnostic tests, surgical treatment, and survival are summarized in Table 1.

Main characteristics of patients at hospital admission from the twenty cases of Legionella endocarditis reported in the medical literature.

| Author | Pub. year | Sex | Age | Pneumonia | Immunosuppression | Valve localization | Valve type | Time from valve Repl. | Clinical presentation | Diagnostic test | Echocardiogram | Valve repl. | Antibiotic | Duration of treatment | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCabe R. | 1984 | Fem | 60 | No | No | Aortic | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) valve culture(+) serology | New regurgitation | Yes | Erythromycin+Rifampin | 6 months | No |

| Littrup P. | 1987 | Fem | 38 | Yes | No | Aortic | Native | Fever | (+) serology | Vegetation | No | Erythromycin | 8 weeks | No | |

| Tompkins LS | 1988 | Male | – | – | – | Aortic and mitral | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) serology(+) valve culture | Vegetation | Yes | Erytromicine+Rifampin | 6 months | No |

| Tompkins LS | 1988 | Male | – | – | – | Aortic | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) serology(+) valve culture | New regurgitation | Yes | Erytromicine+Rifampin | 6 monts | No |

| Tompkins LS | 1988 | Male | – | – | – | Aortic | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) serology(+) blood culture(+) valve culture | Negative | Yes | Erytromicine+Rifampin | 9 months | No |

| Tompkins LS | 1988 | Fem | – | – | – | Mitral | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) serology(+) blood culture(+) valve culture | New regurgitation | Yes | Erytromicine+Rifampin | 14 months | No |

| Tompkins LS | 1988 | Fem | – | – | – | Mitral | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) serology and blood culture | New regurgitation | Yes | Ciprofoxacink+Rifampin | 5 months | No |

| Tompkins LS | 1988 | Fem | – | – | – | Mitral | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) serology(+) blood culture | New regurgitation | No | Erytromicine+Rifampin | 5 months | No |

| Park D. | 1994 | Male | 65 | Yes | No | Aortic | Biological p. | >6 months | HF | (+) serology | New regurgitation | Yes | Doxycycline | 6 months | No |

| Chen | 1996 | Male | 33 | No | No | Ao | Mecanical p. | <6 months | Fever | HC (+)(+) valve | Negative | yes | Erytromicine | 6 months | No |

| Massey R. | 2003 | Male | 28 | Yes | No | Aortic | Biological p. | >6 months | HF | New regurgitation | Yes | Clarithromycin+Rifampin | Unknown | No | |

| Patel MC | 2005 | Male | 63 | No | Yes | Aortic | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) blood culture(+) PCR | Abscess | Yes | Levofloxacin | 36 moths | No |

| Pearce MM. | 2011 | Fem | 68 | No | Yes | Aortic | Native | Chest pain | (+)PCR | Vegetation | Yes | Moxifloxacin | 2 weeks | Yes | |

| Samuel V. | 2011 | Fem | 42 | No | Yes | Aortic | Native | Fever | (+) blood culture(+) urinary antigen. | Vegetation | No | Levofloxacin+Rifampin | 6weeks | No | |

| Fukuta Y. | 2012 | Male | 57 | No | Yes | Mitral | Mecanical p. | >6 months | Brain abscess | (+) PCR | Abscess | Yes | Levofloxacin | 5 months | No |

| Leggieri N. | 2012 | Male | 73 | No | No | Aortic | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) PCR(+) serology | Abscess | Yes | Erytromicine+Ciprofloxacin | 6 weeks | No |

| Thurneysen C | 2014 | Fem | 70 | No | Yes | Mitral | Native | Arthritis | (+) synovial culture | Vegetation | No | Ciprofloxacin | 3 months | No | |

| Compain F. | 2015 | Fem | 58 | Yes | No | Aortic | Native | HF | (+) PCR | New regurgitation | Yes | Levofloxacin | 3 weeks | No | |

| Baumgartner V. | 2016 | Male | 64 | Yes | No | Aortic | Native | Fever | (+) serology | Vegetation | No | Clarithromycin | 6 weeks | No | |

| Young JS. | 2019 | Male | 80 | No | No | Mitral | Biological p. | >6 months | Fever | (+) serology(+) PCR | Vegetation | Yes | Levofloxacin | 6 weeks | No |

The risk factors for the development of Legionella cardiac infections are not well known. A combination of previous medical history of pneumonia, immunosuppression, and prosthetic valves has been reported in the majority of the cases.

Our patient did not have a history of pneumonia or respiratory infection. According to previous reports, five patients (25%) had received a diagnosis of pneumonia; however, the diagnosis of Legionella pneumonia was confirmed in only one patient (ref). In three cases, pneumonia had occurred in the year before the diagnosis of endocarditis and no microorganism had been identified; a fifth case had been diagnosed with Mycoplasma pneumonia one month prior to the diagnosis of Legionella endocarditis.

Although our patient was not immunosuppressed, four of the 20 (20%) cases reviewed had a history of immunosuppression. One patient had undergone renal transplantation and was receiving immunosuppressive treatment; a second patient had hypersensitivity pneumonitis and was treated with corticosteroids; a third patient was undergoing chemotherapy for Hodgkin disease; and the fourth patient had lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome and was being treated with corticosteroids and azathioprine.

Prosthetic valves seem to be the predisposing condition most strongly associated with the incidence of Legionella endocarditis. Out of the 20 reviewed cases, 2 cases (10%) were endocarditis on mechanical prostheses; 12 cases (60%) were endocarditis on biological prostheses; and 6 cases (30%) had occurred on native valves. All the prostheses had been placed at least 6 months before the diagnosis of Legionella endocarditis. Twelve (60%) cases had occurred on aortic valves, six cases (30%) involved the mitral valve; in one case both aortic and mitral valves were affected; the location of the endocarditis in the remaining case was not reported.

Clinical presentationLegionella endocarditis is a chronic disease that presents long after surgery and is characterized, as seen in our patient, by low grade fever. The majority of the cases had a protracted clinical course featured by weakness and fever. Heart failure and chest pain have also been reported, while embolic phenomena have been rare. In our review, one patient presented with a brain abscess and another patient presented with arthritis. Arthritis was prominent in the case that we are reporting along with previously unreported palpable purpura.

DiagnosisThe diagnosis of Legionella endocarditis poses an extraordinary challenge. There is universal agreement in the central role achieved by the Duke criteria in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.16 However, their limitations, which have been pointed out in the scenario for which they were developed (infective endocarditis caused by bacteria regularly grown on standard blood culture media) are particularly noteworthy in the case of Legionella endocarditis. Overall, 15 out of 20 reported cases (75%) can be considered to have received a definite diagnosis: 9 according to the Duke clinical criteria and 11 according to the pathological criteria (six cases fulfilled both types of criteria; four cases diagnosed by clinical criteria did not undergo surgery or had a negative microbiological study of the surgical samples; four clinically “possible” cases were confirmed pathologically; and, notably, two cases clinically rejected were diagnosed only after the identification of Legionella in the surgical samples). Of the remaining 5 cases, one could be rejected and 4 could be possibly considered as Legionella endocarditis with strict application of the Duke criteria. Serologic tests for anti-Legionella antibodies have been positive in 12/13 (92%) cases in which they are reported. They have been instrumental in the etiologic diagnosis in four patients. Unfortunately, serologic testing was not performed in our patient. Conversely, the results of the Legionella urinary antigen test were positive in only 2 of 6 cases in which it was reported.

TreatmentThe treatment of Legionella endocarditis, as that of endocarditis of other etiologies, relies on two pillars: appropriate antibiotic choice (regarding activity, pharmacokinetics, and duration) and appropriate surgical indication. There are no controlled studies to provide firm recommendations relative to the antibiotic choice, duration, or indications for surgery. From our review of reported cases, as summarized in Table 1, the following general statements can be inferred:

- 1.

The prognosis of Legionella endocarditis is favorable, with an overall mortality of less than 10% (including our case).

- 2.

Assuming an appropriate surgical indication for the reported cases, the prognosis appears to be equally good irrespective of surgery, as all six cases treated with medical therapy alone were reported to be cured.

- 3.

Although long treatment-regimens were selected in earlier studies, more recent reports strongly suggest that shorter courses of antibiotics, not exceeding 6 weeks, are likely to cure most cases even in the absence of surgical intervention.

Bacteria of the genus Legionella are well-known; however, they rarely are determined to be the cause of culture-negative endocarditis. A high index of suspicion is necessary for progress in selecting the appropriate diagnostic tests in culture-negative endocarditis, given the poor yield of standard microbiological techniques in the identification of Legionella spp. The clinical course is subacute or chronic and embolic phenomena are rare. Most Legionella endocarditis patients have required valve replacements with good outcomes. PCR from valve material extracted during the surgery seems likely to replace culture for the identification of the bacteria in the material resected during surgery. Both fluoroquinolones and macrolides have been associated with the cure of the majority of the reported cases, with a treatment duration as short as 6 weeks (and shorter in isolated cases).

FundingThis review did not receive grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest.