Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a rare life-threatening disease first described by Todd and Fishaut in 1978. The most characteristic symptoms are fever, rash, hypotension, desquamation and the involvement of multiple organ systems.1 Menstrual TSS (mTSS) is defined when it appears from the beginning of the menstruation and up to four days after.2 mTSS incidence has been reported to be 0.69 in 100,000 menstruating women per year and has been associated with high morbidity and mortality rate in previously healthy women.3

mTSS is caused by superantigen-producing Staphylococcus aureus (SA) or group A Streptococcus, and has been associated with the use of different vaginal devices as tampons or menstrual cups.4 SA superantigen, named toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1), is encoded by tst gene and is responsible for mTSS by its ability to trigger excessive and non-conventional T-cell activation with consequent downstream activation of other cell types, and cytokine/chemokine release.5

We report a case of a 15-year-old menstruating woman who was hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) with suspicion of septic shock in the context of purulent vaginal discharge. The presented symptoms were malaise, fever (38.9°C), sore throat, diarrhoea, rash and painful genital ulcers of 3 days of evolution. Physical examination was remarkable for a low blood pressure (80/50mmHg), diffuse erythematous macular rash and conjunctival hyperaemia. Laboratory assessments on admission revealed elevated inflammatory markers (value obtained – reference range) (CRP 218mg/L – 0.2–5mg/L; PCT 26.65ng/mL – <0.05ng/mL), acute renal injury (creatinine 3mg/dL – 0.51–0.95mg/dL), anaemia (haemoglobin 10.5g/dL), thrombocytopenia (101×109platelets/L) and associated coagulopathy (D-dimers 6634ng/mL – 0–243ng/mL). Upon ICU admission, several samples were sent to the laboratory for bacteriological study and SA was isolated from vaginal, nasal, rectal and axillary swabs, pointing out the mTSS as the most probable diagnosis. Blood cultures remained negative. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed with Panel Type 33 of MicroScan WalkAway using the breakpoints recommended by The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (http://www.eucast.org).

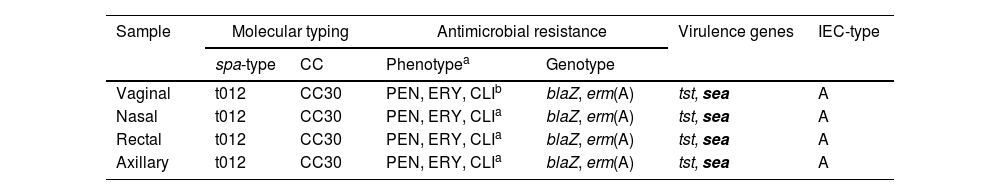

The four SA strains showed the same resistance phenotype (penicillin, erythromycin and clindamycin inducible (MLSBi)); they were sent to the University of La Rioja for detection of (1) virulence genes: tst (encoding TSST-1 toxin), pvl (encoding Panton-Valentine-Leucocidin) and sea, seb and sec (encoding enterotoxins A, B and C); (2) antimicrobial resistance genes (blaZ and ermA/ermB/ermC/ermT); (3) molecular typing (spa-typing and multi-locus-sequence-typing); (4) immune evasion cluster (IEC) system, present in most human SA isolates (the IEC system includes seven different types: from A to E).6

The four isolates were typed as MSSA-CC30-t012 and IEC-type A, they carried the tst gene (verified by PCR/sequencing) but not pvl and they carried the blaZ gene (Table 1); they also carried the sea gene but not seb or sec genes. The prevalence of CC30 SA has been considerably reported in several European countries7,8; and a study performed in the UK revealed a strong association of the tst-positive CC30 SA lineage with mTSS and TSS cases.9

Characterization of the four Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from the patient with menstrual toxic shock syndrome.

| Sample | Molecular typing | Antimicrobial resistance | Virulence genes | IEC-type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spa-type | CC | Phenotypea | Genotype | |||

| Vaginal | t012 | CC30 | PEN, ERY, CLIb | blaZ, erm(A) | tst, sea | A |

| Nasal | t012 | CC30 | PEN, ERY, CLIa | blaZ, erm(A) | tst, sea | A |

| Rectal | t012 | CC30 | PEN, ERY, CLIa | blaZ, erm(A) | tst, sea | A |

| Axillary | t012 | CC30 | PEN, ERY, CLIa | blaZ, erm(A) | tst, sea | A |

However, mTSS primarily remains a clinical diagnosis, and indeed, the isolation of SA tst+ is not required for diagnosis of the disease.5 Moreover, in Spain and other countries in Europe, TSS is not a notifiable illness, so the clinical, microbiological, and toxigenic features of TSS remain poorly described.

The patient was empirically treated with cefotaxime and metronidazole. Metronidazole was discontinued and clindamycin was added when SA was reported. After antibiotic susceptibility testing, treatment changed from cefotaxime to cloxacillin and, since the patient was presenting a favourable evolution, clindamycin was maintained. The patient was discharged from ICU setting 2 days after admission, and sent home on the 8th day of hospitalization.

This case evidences the persistence of mTSS cases, which may be fatal, even leading to patient's death.10 Thanks to the early diagnosis and the prompt implementation of vital support and antibiotic treatment, our patient had a good outcome.

ConclusionsDue to its rarity and initially unspecific symptoms, patients with mTSS are at risk of misdiagnosis. Even though molecular methods are not available in many laboratories, its implementation should be considered since they represent a possibility for faster diagnostics, and to obtain more information for the clinical and epidemiological surveillance of mTSS/TSS-associated SA lineages.

FinanceThe experimental work performed in the University of La Rioja was financed by project of MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 of Spain. R. Fernandez-Fernández has a predoctoral contract from the Ministry of Spain (FPU18/05438).