Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare infection caused by pigmented or dematiaceous (phaeoid) fungi.1 From 1980 to 2020, about 90 cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei were reported.1 This is the case of a female diabetic patient with a single subcutaneous cyst as the only manifestation of E. jeanselmei infection.

The patient was a 64-year-old woman who had been diabetic for 15 years, treated with vildagliptin/metformin, with a one-year clinical history that started as a hyperpigmented papule on her left knee, evolving into a subcutaneous cyst (Fig. 1A and B), with occasional pain and haemopurulent discharge. There were no inflammatory signs or history of trauma.

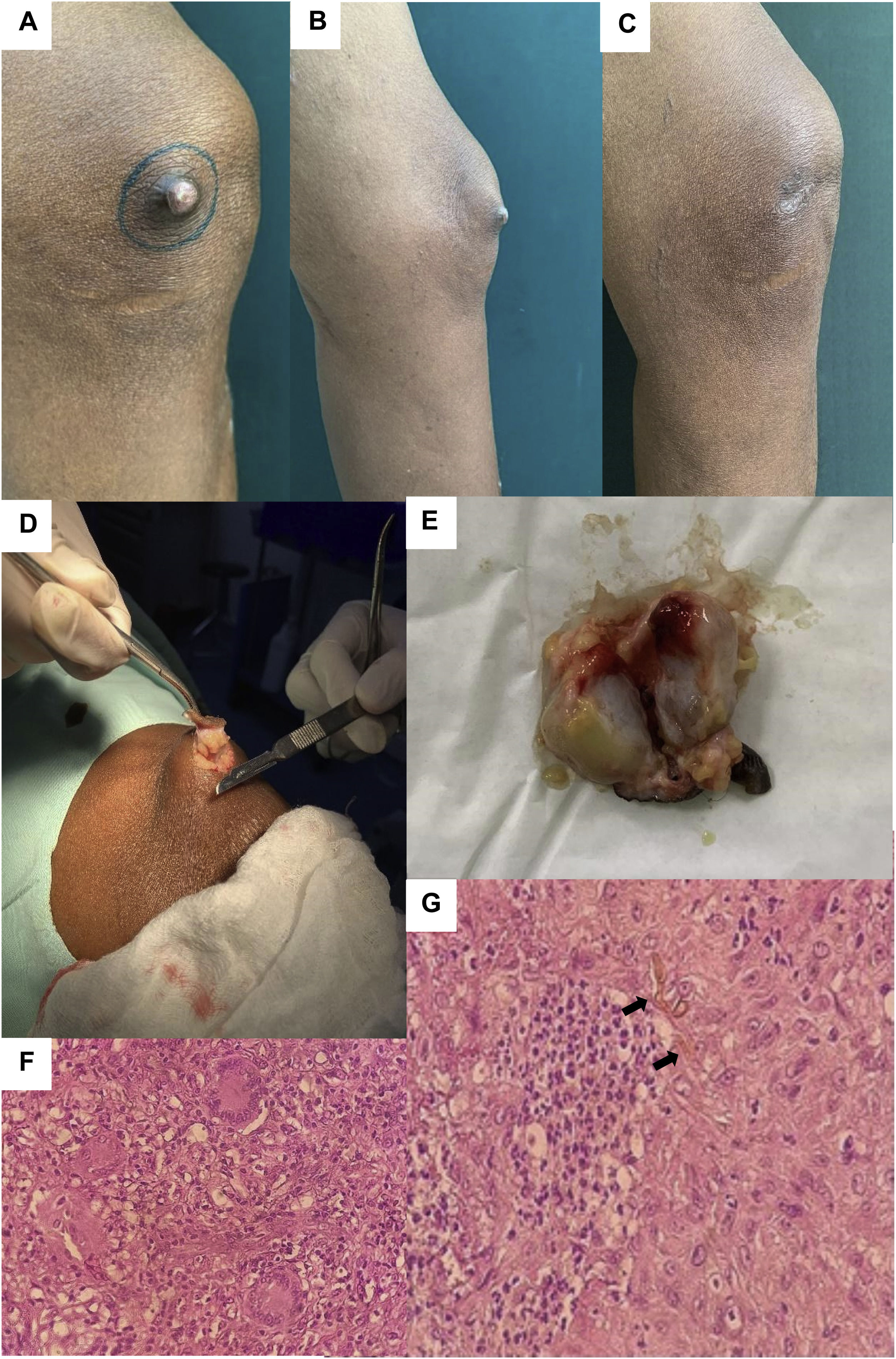

A) Subcutaneous cyst on the left knee. B) Side view. C) Post-surgical scar at five months, without recurrence. D) Surgical excision of the subcutaneous cyst. E) Gross specimen encapsulated, bilobulated, with yellowish discharge. F) Histopathology with inflammatory infiltrate and multinucleated cells (H&E 40×). G) Histopathology with inflammatory infiltrate, necrosis and septate pigmented hyphae (black arrows) (H&E 40×).

Soft tissue ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic bilobulated image containing echogenic fluid material. Direct examination revealed septate pigmented hyphae and culture of the discharge isolated E. jeanselmei complex. As susceptibility testing was not available, itraconazole was indicated empirically due to its better efficacy profile against yeast microorganisms, at a dose of 200mg/day for one month, before and after surgical excision. A 3×2-cm rubbery bilobulated cyst with yellowish discharge was removed (Fig. 1D and E). Histopathology showed fibrous connective tissue with extensive necrosis and neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate, surrounded by lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and multinucleated giant cells, (Fig. 1F) and septate pigmented hyphae (arrow, Fig. 1G). There has been no recurrence to date (Fig. 1C).

More than 150 species and 70 genera of phaeoid fungi have been reported in phaeohyphomycosis, including Alternaria, Exophiala, Wangiella, Cladosporium, Phialophora, Fonsecaea, Curvularia and Bipolaris.2Exophiala is one of the three most common, primarily E. dermatitidis and E. jeanselmei.3 This genus is increasingly reported as a causative agent of cutaneous, subcutaneous or invasive infection, with E. jeanselmei also being associated with eumycetoma.4 They are found in the environment and are opportunistic and saprophytic.1 They have melanin in the cell wall, which acts as a potent free radical scavenger and protector against proteolysis and phagocytosis.5

Despite exposure to these fungi through inhalation of conidia, development of infection is rare1, and when it does occur it is associated with traumatic inoculation6. It affects men more often due to higher occupational exposure to contaminated soil and vegetation2, and is more prevalent in the tropical countries of Central and South America2.

Most patients are immunocompromised2, but in the fungal cyst variety half are immunocompetent3 in whom homozygous CARD9 mutations have been reported. However, further studies are required to recognise other mutations and to understand those described to date.1,7

Manifestations are variable, non-specific and generally asymptomatic.5 Lesions are usually isolated and in exposed areas such as the limbs.5 The most common clinical form is superficial, with cutaneous, ungual, otic or ocular involvement.1 The subcutaneous variety presents as disseminated nodules, tumefaction or fungal cyst, as in our patient, and may mimic skin and soft tissue neoplasms.8

Deep local infection is unusual, with paranasal sinus, osteoarticular, intestinal or ocular involvement.1 Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk of severe invasive disease and systemic dissemination9, mainly affecting the lung, and less so the central nervous system1,2. A mortality rate of 10% in deep local infections and 50% in disseminated infections has been reported.1

Histopathology and mycology are the cornerstones of the diagnosis.1 Characteristically they show blackish-brown, septate hyphae of variable size, pseudohyphae and sometimes blastoconidia, depending on the species.1 Histopathology shows fungal elements in more than 80% of specimens, associated with a non-specific inflammatory or granulomatous dermal infiltrate.9 Pigmented hyphae can be highlighted with Gomori-Grocott or Fontana-Masson staining to reveal melanin, although it is not 100% specific.1 Isolation is on Sabouraud agar or potato dextrose medium at 30°C, with growth averaging one to three weeks.1

There is no standardised treatment.1 The first line treatment is surgical excision associated with systemic antifungals5,6 such as itraconazole or terbinafine, before and after excision to minimise recurrences, and in case of poor response, voriconazole, amphotericin B or 5-fluorocytosine.2,7 The use of systemic antifungal agents with local thermotherapy is another alternative.7

The inherent difficulty in establishing a clinical diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis and the significant therapeutic challenge it entails must be highlighted. This case raises awareness of the importance of including it in the differential diagnosis of nodulocystic lesions.

Informed consentThe informed consent of the patient was obtained.

FundingNo funding was received.