(1) to design a training programme for newly hired nursing personnel and (2) to determine self-perception and perceived stress before and after the theoretical and practical parts of the programme with high fidelity simulation activities.

MethodsA pilot quasi-experimental pretest-posttest study without control group conducted in a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit from October 2018 to April 2019 was conducted. A newly hired nursing personnel training programme was first designed and delivered. Later, the participants’ self-perception was assessed, as well as their perceived stress and grade of satisfaction using two different Likert scales.

ResultsA total of 20 newly hired nurses participated in the study, 90% (n = 18) were female with a median age of 25.5 ± 4.53 years. Higher scores were obtained in participants’ self-perception before and after the theoretical training. Lower significant median scores of the participants’ stress perception were found (6.9 ± 1.57 versus 5.6 ± 1.794). In the practical part of the programme, we obtained higher scores in all items, as well as lower median scores in stress perception (6.4 ± 1.73 versus 5.6 ± 1.93).

ConclusionsA theoretical and practical programme for newly hired nursing personnel in a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit improved participants’ self-perception and reduced their perceived median scores in stress levels.

(1) Diseñar un plan formativo de acogida a enfermeros de nueva incorporación y (2) determinar la autopercepción y el estrés percibido antes y después de la realización de la parte teórica y de la parte práctica con simulación de alta fidelidad.

MétodoSe llevó a cabo un estudio piloto de diseño cuasiexperimental tipo pretest-postest sin grupo control en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos, de octubre de 2018 a abril de 2019. En primer lugar, se diseñó un plan formativo teórico y práctico que se impartió a todo el personal de nueva incorporación de la unidad. Posteriormente, se evaluó la autopercepción personal, el estrés percibido y el grado de satisfacción mediante dos escalas tipo Likert.

ResultadosParticiparon en el estudio un total de 20 enfermeros/as de nueva incorporación, el 90% (n = 18) eran del sexo femenino, con una edad media de 25,5 ± 4,53 años. Al comparar los datos obtenidos pre y post formación teórica en relación a la autopercepción personal se constató un aumento de puntuación en todos los ítems. A la vez, se objetivaron puntuaciones medias menores de estrés (6,9 ± 1,57 versus los 5,6 ± 1,794). En la parte práctica se obtuvo también un aumento de las puntuaciones, así como una tendencia a la disminución de las puntuaciones medias globales de estrés percibido (6,4 ± 1,73 versus 5,6 ± 1,93).

ConclusionesUn plan de acogida teórico-práctico mediante SC impartido a profesionales de enfermería de nueva incorporación de una UCIP mejoró su autopercepción sobre el nivel de conocimientos y disminuyó las puntuaciones medias de estrés.

Comprehensive and nursing care for critically ill paediatric patients is highly complex. Moreover, these particular patients have anatomical and physiological characteristics that differ from those of adults and make them more vulnerable. For all these reasons, in order to be able to offer quality health care, the health care staff caring for these patients must have specific knowledge and training.

What it contributesThere is little research on the level of stress experienced by newly trained nurses, due to lack of knowledge. The study presented here shows an example of a theoretical and practical training programme created on the basis of the needs of the trainees. At the same time, piloting this plan with a total of 20 new nurses favoured self-perception in line with the acquisition of competencies. At the same time, there was a trend towards a decrease in mean stress scores.

Implications for practiceGiven the scarcity of content guides related to training programmes focussed on the context of paediatric critical care, the present study could assist in the development of training material to be introduced into other Spanish PICUs and, thus, improve the quality of health care and the safety of critical patients being treated there.

The comprehensive care and management of critically ill patients is highly complex. These patients suffer from pathology-related problems that are so severe that their lives are potentially or actually at risk. Consequently, their management requires complex strategies and treatments. In addition, their pathophysiological evolution is characterised by significant changeability and their clinical condition can vary rapidly, with the time taken to act being vital in the prognosis and development of morbidities.1

In the case of paediatric patients, all these issues become even more relevant. Children who are critically ill have anatomical and physiological characteristics that differ from those of adults and make them more vulnerable to any external aggression. For this reason, the health care personnel caring for them must have specific knowledge and training.2

For all these reasons, critical paediatric patients must be cared for in Paediatric Intensive Care Units (PICUs), which are characterised by being very technical areas with a high degree of complexity. In these units, clinical and nursing care is not free of complications and risks. In PICUs, invasive procedures are undertaken, clinical devices are installed, and drugs are administered, all with great potential for side effects in the patient.3

Insufficient training, lack of experience in paediatric critical patient care and/or lack of knowledge of protocols and working dynamics increase the risk of making mistakes related to clinical practice. All these aspects compromise patient safety and quality of care.3 One of the main problems faced by nurses joining PICUs is that they experience difficulties with the practice of care due to workload, lack of skills and technological advances.

To ensure safe care for critically ill patients, risks must be managed and the number of errors and adverse events that can occur must be reduced. In this regard, one of the key points is to introduce training programmes to train new staff who are recruited or transferred for the first time to a PICU.

Scientific evidence demonstrates the need for theoretical and practical training programmes for new nurses starting work in PICUs,4–7 The design of these education programmes varies, although they all consist of theoretical classroom teaching and guided clinical experience.6,8

Regarding training methods, there is evidence to support the effectiveness of clinical simulation (CS) as compared to learning by traditional methods, especially in the critical care setting.1,9 The Harvard Simulation Center defines this as: “a situation or place created to enable people to experience the enactment of a real event for the purpose of practising, learning, evaluating, and understanding human systems or actions.10 This learning methodology can be applied to any professional, regardless of seniority and in almost all health care settings with a high risk of patient adverse events. It is particularly relevant in PICUs, as it provides scenarios that mimic clinical settings and enable professionals to acquire skills and confidence, as well as reinforcing skills and knowledge.11,12 For this reason, the World Health Organisation (WHO) suggests the use of CS on training programmes to promote patient safety.11,12 Moreover, this method is recognised as an important one in nursing, as staff training is essential to increase the quality of care.13–15

In view of the above, the specific training of PICU nurses is an essential aspect to be taken into consideration. However, due to the current situation of high demand for health care personnel in health centres and the retirement of senior professionals, this is difficult to set up and maintain.1 As a result of all the above, the need has arisen to implement a theoretical and practical training programme, using CS, for new nurses and also to assess the effectiveness of this intervention in a PICU.

The general aim of this research was to analyse the effectiveness of a theoretical and practical training programme for nurses who joined a PICU between October 2018 and April 2019. The specific objectives of this research were as follows: (1) to design a theoretical and practical training programme through SC for new nurses and (2) to determine the nurse’s own perception and stress felt before and after completing the various parts of the training programme.

Material and methodsA semi-experimental pre-test and post-test type pilot study was designed without a control group. The setting was a PICU at an international benchmark paediatric tertiary care hospital with 28 beds: 24 for critical care patients and four for semi-critical cases. The study period ran from October 2018 to April 2019.

The study population consisted of nurses who joined the PICU in the selected hospital between October 2018 and April 2019. The training programme was conducted over two periods, coinciding with two groups of nurses entering the PICU.

Study participants were selected by non-probability convenience sampling, taking into consideration the following selection criteria:

- -

Inclusion criteria

- o

Graduate in possession of a degree in Nursing.

- o

Nurses from another health care unit transferred for the first time to a PICU.

- o

Second year residents in the speciality of paediatric nursing prior to PICU rotation.

- o

Acceptance and signature of informed consent.

- o

- -

Exclusion criteria

- o

Resignation from the employment contract in the hospital running the study.

- o

The main study variables were divided as follows:

- -

Sociodemographic variables: age (in years) and sex (male/female).

- -

Variables referring to the professional information on the participants: length of service as a nurse (in months), experience in ICUs (yes/no) and experience in paediatrics (yes/no).

- -

Determination of training needs by means of an ad hoc survey.

- -

Personal self-perception, determined by means of an ad hoc Likert-type questionnaire from 1 to 10, with 1 being no qualifications whatsoever and 10 highly qualified.

- -

Perceived stress, determined by means of a Likert-type scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being zero stress and 10 the highest possible stress.

- -

Degree of satisfaction, determined at the end of the induction programme using a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5, with 0 being extremely dissatisfied and 5 being highly satisfied.

The main instruments used in this project were:

- 1

Ad hoc survey to work out the training needs and concerns of the study population, designed using the Google Forms® programme. The first part included five questions on socio-demographic data (age, sex, years working as a nurse, experience in paediatrics and paediatric intensive care). Subsequently, using a Likert scale from 0 to 5 (0 not at all relevant and 5 highly relevant), participants were asked to assess the relevance of including the following items in a theoretical and practical training programme: organisation and structure of the PICU; action taken on admission of a paediatric critical patient; invasive and non-invasive monitoring; most commonly used venous catheters in the paediatric critical care area; knowledge of paediatric pharmacology and nursing care for paediatric patients with a respiratory pathology; and post-operative cardiovascular, trauma and neurosurgical surgery. These items were selected on the basis of the literature consulted. The survey was sent out by e-mail to all nurses who agreed to participate in the study and who had signed the informed consent form.

- 2

An ad hoc instrument that was designed to include some of the questions from the Self-confidence Scale after it had been culturally adapted and validated for nursing students.16 To design the study instrument, the main researchers selected the most relevant items from the Self-confidence Scale that could be most useful, given the context of the study and the literature consulted. To ensure that the instrument included all essential items, it was assessed by a group of five expert nurses with more than five years of professional seniority in the paediatric critical care setting. The resulting ad hoc instrument consisted of eight questions, one for each item included in the training programme. The participants rated from 1 to 10 their level of competence and knowledge in relation to the management of paediatric critical patients, with 1 being the lowest value and 10 the highest one.

- 3

A Likert-type perceived stress scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no stress and 10 the highest possible stress. Its design was based on the scale used in a study with a sample of 107 nursing students, where stress was assessed before and after a clinical simulation intervention.17,4

- 4

A Likert-type satisfaction survey from 0 to 5, with 0 representing the lowest degree of satisfaction and 5 the highest. This instrument was created taking into account the “Quality and Satisfaction Survey on Clinical Simulation”.18 This was divided into two blocks: theoretical and practical. The evaluation of both theoretical and practical training was divided into four sub-sections: methodology, teaching staff, usefulness of the induction programme, and a free expression section. In addition, an overall assessment of the induction programme was included.

After obtaining verbal and written informed consent from all participants, the study was begun by determining training needs. To this end, the link to the ad hoc questionnaire designed for this purpose was sent out by e-mail. Once all the responses had been obtained, the theoretical and practical training programme was designed. This took three days (Appendix A): two for the theory and one for the clinical simulation. For the practical training with a high-fidelity simulation, an infant manikin (SimBaby by Laerdal®) and a simulation room in the PICU were used in the study. The cases were based on common clinical situations in the PICU (Appendix A).

The teachers were nurses with more than five years of professional experience in the critical care setting. A nurse trainer in this methodology collaborated with the SC.

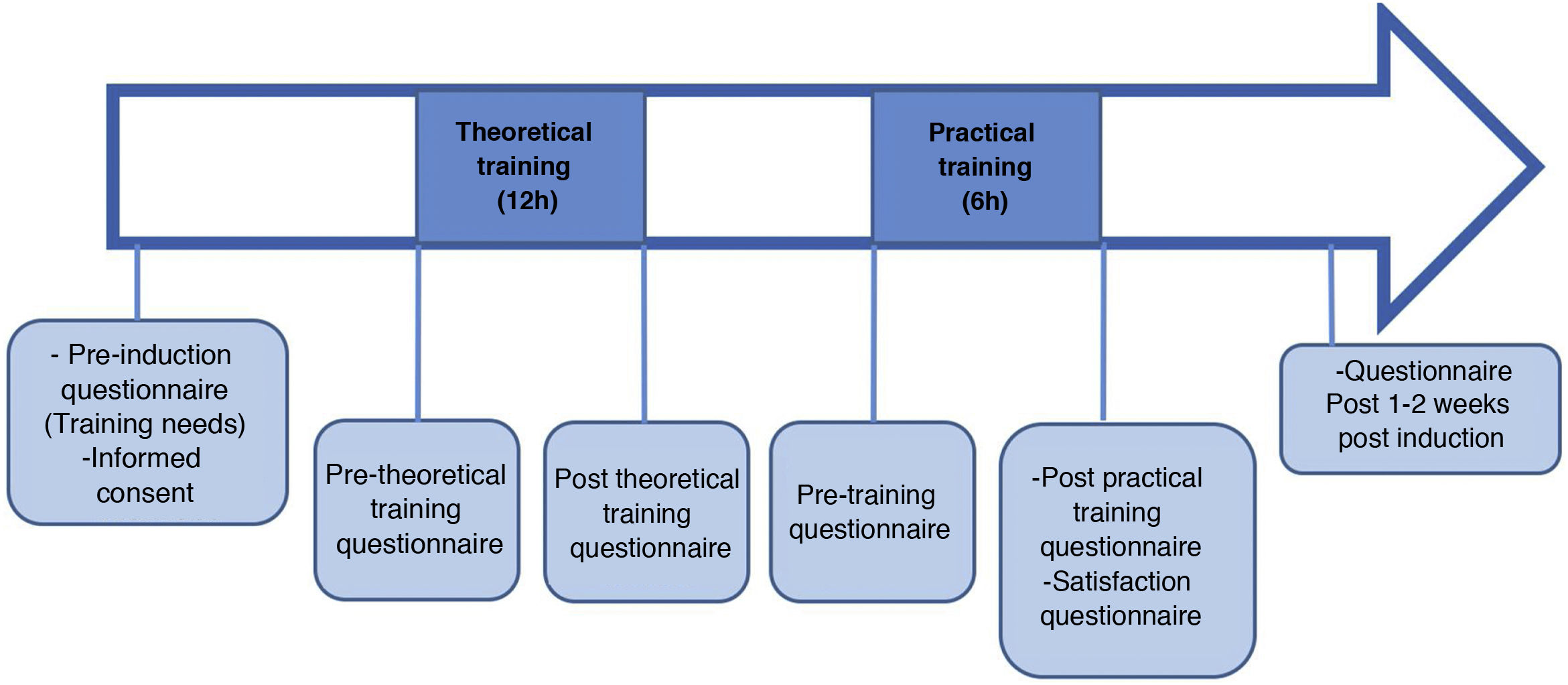

Data related to personal self-perception and perceived stress was collected in person by means of an anonymous questionnaire. Anonymity was ensured by providing each participant with a sealed envelope with a number from 1 to 20:

- -

Before running the theoretical training (the first day of the training programme).

- -

After the theoretical training (at the end of the second day of the training programme).

- -

Before the practical training (at the beginning of the third day of the training programme).

- -

After the practical training (at the end of the third day of the training programme).

- -

One week after completion of the induction programme and after the new nurses had started their work or rotation in the PICU context of study.

- -

After completing the practical training and, therefore, the induction training programme, the satisfaction questionnaire was sent out. Fig. 1 graphically summarises the data collection process.

For data handling and storage, a database was designed using the IBM SPSS® v.23 statistical software.

A descriptive analysis of the sample was drawn up. Numerical variables were expressed using descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, quartiles and interquartile range) and categorical variables were described using frequency tables with percentages.

To compare the values of a numerical variable before and after the intervention, the Student’s t test was used for paired samples, or the non-parametric Wilcoxon test, depending on their distribution.

Results with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerationsPermission to run the study was requested from the head of the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit and the Clinical Research and Ethics Committee (CEIC in its Spanish acronym) of the hospital where the study was conducted (PIC-15-19).

For the handling of information obtained, the commitment to non-maleficence, fairness, beneficence and autonomy from the Belmont Report (1978)19 was ensured. For this purpose, verbal and written informed consent was requested beforehand from all participants. In addition, absolute confidentiality, anonymity and privacy were guaranteed throughout the process of handling personal data, thus complying with the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union 2016/679, applicable in Spain since May 2018, as well as Basic Law 41/2000 Regulating Patient Autonomy, on rights and obligations regarding clinical information and documentation.

ResultsThe theoretical and practical induction programme was given to a total of 20 nurses, which corresponded to 100% of all new recruits during the study period. Of these, 90% (n = 18) were female, with a mean age of 25.5 ± 4.5 years. The median time elapsed between completion of undergraduate studies in nursing and joining the PICU was 13.6 months [0–48]. Of the total number of professionals, 40% (n = 8) had previous professional experience in adult ICUs and 45% (n = 9) in paediatrics (Table 1).

Socio-demographic features of the sample (n = 20).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 18 (90%) |

| Male | 2 (10%) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 25.5 ± 4.53 |

| Months of experience working as a nurse, median and LR | 13.65 [0–48] |

| Experience in paediatrics | |

| Yes | 9 (45%) |

| No | 11 (55%) |

| Experience in ICU (adults) | |

| Yes | 8 (40%) |

| No | 12 (60%) |

SD: Standard Deviation.

IR: Interquartile Range.

The most relevant aspects of the ad hoc survey to detect training needs were: “action on admission” (score 4.90 ± 0.3 out of 5), “basic care of paediatric patients with respiratory pathology: invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation” (score 4.8 ± 0.3 out of 5) and “post-operative cardiovascular surgery patients” (score 4.8 ± 0.4 out of 5) (Table 2). In the open-ended questions, participants suggested addressing issues related to Cardiorespiratory Arrest (CRA) or accidental extubation. A total of 83.3% of the participants agreed on combining master classes with practice using clinical simulation.

Assessment of items to be included in the training, following an online survey of new nurses (n = 20).

| Items included in the training programme | Score (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Organisation and structure of the intensive care unit | 4.4 ± 0.8 |

| Action on admission of critical paediatric patients | 4.9 ± 0.3 |

| Invasive and non-invasive monitoring on critical paediatric patients | 4.5 ± 0.8 |

| Most commonly used venous catheters in the PICU | 4.6 ± 0.5 |

| Basic notions of paediatric pharmacology | 4.6 ± 0.7 |

| Basic care for paediatric patients with respiratory pathology: invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 4.8 ± 0.3 |

| Comprehensive management and basic care of postoperative patients after cardiovascular surgery | 4.8 ± 0.4 |

| Comprehensive management and basic care of post-operative patients after trauma pathology: scoliosis. | 4.3 ± 0.8 |

| Comprehensive management and basic care of postoperative patients after neurosurgery: craniosynostosis. | 4.6 ± 0.6 |

Minimum possible score 0/maximum score 5.

SD: Standard Deviation.

When comparing the data obtained pre and post theory training, there was an increase in all items, except for “training in medication preparation” (Table 3).

Personal self-perception before and after theoretical training (n = 20), practice (n = 17) and training programme (n = 20).

| Item on the Theory programme | Value obtained, mean ± SD | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre theory | Post theory | Sig. Bilateral* | Pre practice | Post practice | Sig. Bilateral* | Pre-training programme | Post-training programme | Sig. Bilateral* | |

| Ability to handle admissions of critical paediatric patients | 4.8 ± 2.2 | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 0.04 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 7.1 ± 1.2 | 0.04 | 4.8 ± 2.2 | 7.4 ± 1.2 | <0,01 |

| Ability to handle devices in critical paediatric patients | 6.5 ± 1.4 | 7.0 ± 0.9 | 0.01 | 7.0 ± 1.2 | 7.4 ± 1.2 | 0.18 | 6.5 ± 1.4 | 7.9 ± 1.0 | <0,01 |

| Trained to prepare medication for critical paediatric patients | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 7.3 ± 1.4 | 0.85 | 7.6 ± 1.0 | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 0.07 | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 8.3 ± 0.8 | <0,01 |

| Trained to provide care to paediatric patients with respiratory pathologies: mechanical ventilation invasive and non-invasive | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 7.3 ± 1.1 | <0.01 | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 7.1 ± 1.2 | 0.05 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 7.5 ± 0.7 | <0,01 |

| Trained to undertake basic care for paediatric postoperative heart surgery patients | 4.4 ± 2.0 | 5.8 ± 1.9 | <0.01 | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 1.6 | 0.05 | 4.4 ± 2.0 | 6.5 ± 1.2 | <0,01 |

| Trained to admit and provide care to paediatric postoperative patients after: cranio-synostosis neurosurgery | 4.9 ± 2.0 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 0.05 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 0.00 | 4.9 ± 2.0 | 6,8 ± 1,1 | <0,01 |

| Trained to admit and provide care to postoperative paediatric patients after traumatology: scoliosis | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 6.4 ± 2.2 | 0.13 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 7.2 ± 1.5 | <0.01 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 1.0 | <0,01 |

| Prepared to handle life-threatening situations in paediatrics | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 5.8 ± 1.7 | <0.01 | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 6.2 ± 1.5 | <0.01 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 5.8 ± 1.3 | <0,01 |

SD: Standard Deviation.

According to the nurse’s self-perception before and after the clinical simulation, all measured scores increased (Table 3).

Scores of 6.9 ± 1.5 vs. 5.6 ± 1.8 for perceived stress were obtained before and after the theoretical training. At the same time, there was a decrease in the overall scores (6.4 ± 1.7 vs. 5.6 ± 1.9) (Table 3).

Post-training and after one weekAn increase in mean training-related self-perception scores was observed, with statistical significance for all items. Table 3 summarises the training scores obtained pre- and post-training in theory, practice and on the training programme.

At the same time, there was a decrease in mean stress scores (6.9 ± 1.6 vs. 6.0 ± 1.7), although no statistically significant results were obtained (Table 4).

Individual stress before and after each stage of the new PICU entrants’ training programme.

| Time of assessment | Value, mean ± SD | P value* |

|---|---|---|

| Theory | ||

| Pre | 6.9 ± 1.57 | 0.07 |

| Post | 5.6 ± 1.94 | |

| Practice with clinical simulation | ||

| Pre | 6.4 ± 1.73 | 0.04 |

| Post | 5.6 ± 1.93 | |

| After 1 week of the programme | 6.0 ± 1.76 | 0.09 |

SD: Standard Deviation.

This programme for new entrants obtained an overall satisfaction rating of 4.7 ± 0.4 out of 5 points. The usefulness of the theoretical part scored 4.7 ± 0.4, while the part combining theoretical and practical scored 4.9 ± 0.2 out of 5.

DiscussionThe results of the present study show how a training programme combining theory and clinical simulation improved self-perception of the acquisition of competence.20,21 At the same time, there was a trend towards a reduction in the mean perceived stress scores for new professionals in PICUs, a fact that could be definitively confirmed by increasing the sample size. These results were similar to those of other studies. A research project where a simulation programme was run, in which laparoscopic surgical techniques were practised, showed an increase in theoretical and practical knowledge in 93% of the participants. Most of the participants pointed out that clinical simulation was an essential methodology in clinical training.22 Although Nazim et al. did not measure the level of self-perception, they did find an overall increase in knowledge level of 12.7 ± 6.8% when running a medical training plan for surgical urology residents.23

The majority of participants in this research project suggested a learning methodology that would combine the theoretical and practical as more effective. In addition, higher skill-building scores and lower perceived stress scores were obtained after teaching content where theory and SC were combined. This is consistent with research showing that the reduction in perceived stress was greater when both methodologies were combined.1,24,25 One of these was a study undertaken in Singapore on a group of 94 fin. l year nursing students, where a training programme with SC was adopted. This intervention led to an increase in knowledge levels from 97.86 ± 15.08 points at pre-test to 117.21 ± 15.17 at post-test, p < 0.01.26 Boling et al., in their research on nurses in a cardiothoracic ICU also described an increase before and after the SC training programme in both knowledge level (48.18 ± 14.7 vs. 60.9 ± 22.6; p < 0.05) and self-perception (20.8 ± 5.17 vs. 25.9 ± 3.3; p < 0.05).27 Therefore, it could be affirmed that the use of CS favours the acquisition of knowledge and skills in new professionals.3 This fact was reinforced by Boling et al. in an integrative review where they concluded that this teaching methodology improved the level of knowledge and confidence of the participants in critical care units.1 Smallheer et al.28 and Ballangrud et al.29 also reached the same conclusion in their studies on critical care nurses, who perceived an increase in self-confidence, knowledge and a high degree of satisfaction with the methodology used. Although only one CS session was conducted in the research, one study shows that multiple sessions should be conducted to ensure an increase in the knowledge transmitted.1 At the same time, it is important to take into account aspects such as the previous experience of the professional in CS or the type of critical event to be practised.29

The results of the research have shown a trend towards a decrease in the average stress scores of health care professionals before and after the training programme. This is consistent with a clinical trial conducted in several adult intensive care units in France.30 A possible explanation for this decrease in stress is provided by Ballangrud et al. in a study conducted in Switzerland, where they interviewed 18 intensive care nurses after SC training. One of the aspects that the nurses highlighted most was that SC practice improved their own perception of the critical care setting and the need for specific knowledge, as well as the importance of working in structured teams. The nurses also pointed out that practising in realistic scenarios, such as those offered by CS, contributed to improving safe care, encouraged reflection and learning.31

There is not much scientific evidence regarding training programmes that combine theoretical and practical training with SC for new nurses in PICUs. Even so, the benefits of this methodology in relation to critical thinking; the acquisition of practical skills related to teamwork; and the ability to act in critical situations have all been observed. The study by Rice et al., run on nurses in a trauma ICU, showed an increase in the scores obtained in the Trauma Team Performance Observation Tool (TTPOT) for communication and mutual support.32 The use of CS favours the consolidation and increase in the theoretical knowledge acquired1,33–35 because it helped to make this knowledge applicable to possible real-life scenarios. This led to an improvement in self-confidence and personal confidence1,34,36–39 and reduced stress in new health care professionals. However, Armenia S et al. point out that there is insufficient evidence to support the effect of CS training on patient health outcomes, and future research should be pointed in this direction.40

No consensus has been found in the scientific literature on what items should be included in a training programme focussed on critically ill paediatric patients.8,41 Rice et al. point out that aspects such as communication, leadership, monitoring and mutual support should be included in these training programmes.33 Pubudu De Silva et al. add to these items the following: identifying critical situations or conditions, leadership skills, the role of nurses during intubation and care of the ventilated patient, interpretation of diagnostic tests and recognition/management of shock and infection.42

Eppich et al. state that it is essential to detect the real training needs of the student profile, to ensure that intervention on training respond to their real expectations and have an impact on their learning process.15 For this reason, the present study began by determining the training needs prior to developing the training programme aimed at new nursing professionals.

The main limitation of the study was determined by the small research sample. However, as no training programmes focussing on paediatric critical care units were found in the literature consulted, the present study opens the way for future lines of research. Subjectivity in the self-perception of study participants and the fact of including nurses with experience in adult ICUs was another of the limitations existing. The inability to extrapolate the results externally, as well as the fact of not having any specific instruments adapted to the objectives of the project were also aspects to be taken into consideration. Another important issue to be borne in mind was pointed out by Boling et al., concerning the uncertainty of the duration and number of specific CS sessions needed to achieve an improvement in knowledge and self-perception.1 Although the present study showed an improvement in the acquisition of skills, as well as a trend towards a decrease in the mean scores of perceived stress, one of the limitations of this study stems from the fact that only one CS session was run. For this reason, the intention is to continue providing the training programme designed for all new personnel who come to the PICU within the category of study participant. Future research could analyse whether the socio-demographic or occupational variables of new professionals in a PICU interfere with self-perception and perceived stress.

ConclusionsPrior detection of the nurses’ training needs made it possible to design a training programme focussed on the professional profile that it was aimed at. In addition, this theoretical and practical induction programme adopting SC given to new nurses in a PICU, improved the nurses’ own perception of their level of knowledge and tended towards a reduction in mean stress scores, as was observed.

FundingThis work has not received any type of funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.