To determine the opinion and describe the attitude of different health professionals on suitability of therapeutic effort.

MethodMulti-centre, cross-sectional observational study carried out with nurses and doctors who work in the paediatric intensive care units of four hospitals in the Madrid region. A self-administered questionnaire, previously piloted to assess its viability, was used and a sealed box was set up at the nursing station to hand it in. The analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0 software.

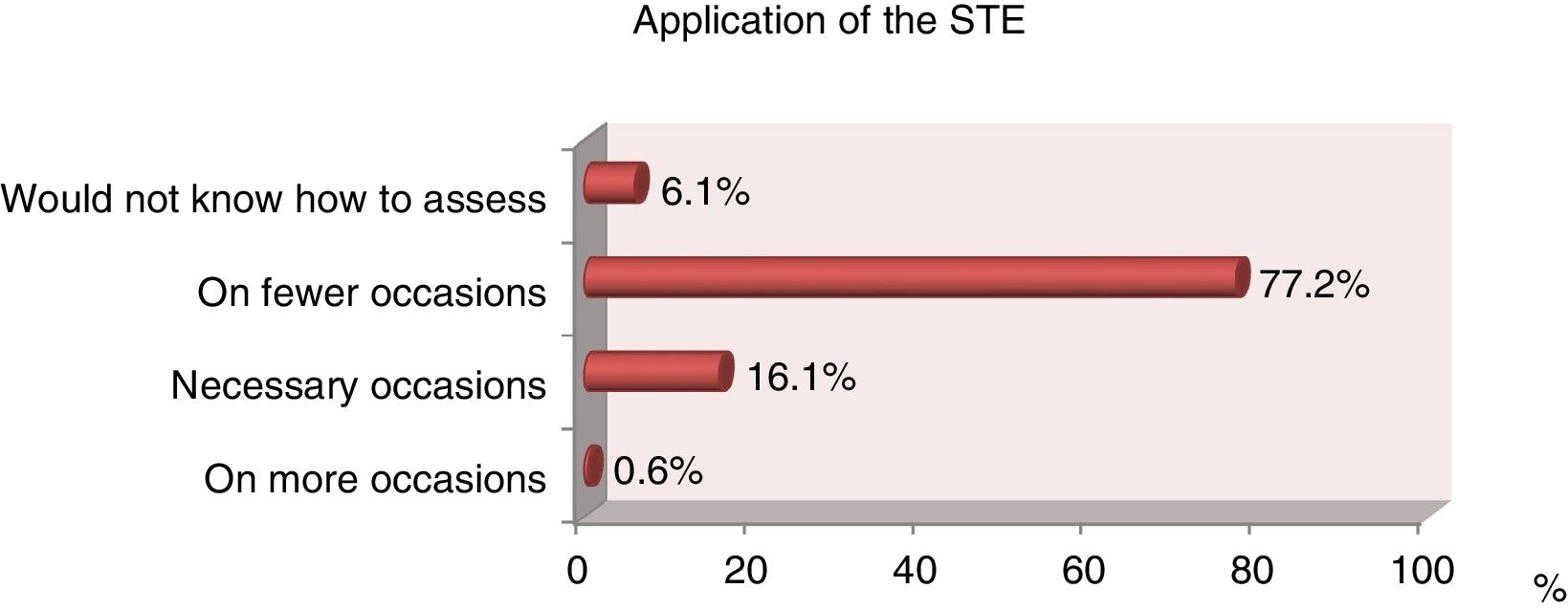

Results98.9% of the respondents were in favour of suitability of therapeutic effort. Doctors consider that the decision is made with the agreement of the multidisciplinary staff and the child’s parents (48.8%). Of the nurses, 51.1% believe that the decision is made by agreement with the doctors and parents. Of the nurses, 65.5% state that they are never asked about decision-making for their patients. Of the doctors, 75% are always or almost always asked. Fifty-seven percent of the nurses and 83% of the doctors feel capable of making decisions about suitability of therapeutic effort. Of the professionals, 77.2% believe that suitability is used less often than required.

ConclusionsThere are differences between doctors and nurses both in the perception of the decision-making model and in the way to proceed. Professionals seem not to follow any protocols or circuits in the decision-making process.

Conocer la opinión y describir la actitud ante la adecuación del esfuerzo terapéutico de diferentes profesionales sanitarios.

MétodoEstudio multicéntrico, observacional y transversal realizado con enfermeras y médicos que desarrollan su labor asistencial en las unidades de cuidados intensivos pediátricos de cuatro hospitales de la Comunidad de Madrid.

Se utilizó un cuestionario de elaboración propia pilotado para valorar su viabilidad y se habilitó una urna clausurada en el control de enfermería para que fuera depositado. El análisis se realizó con el programa SPPS 21.0.

ResultadosEl 98,9% de los encuestados declaró estar a favor de la adecuación del esfuerzo terapéutico. Los médicos consideran que la decisión se toma por consenso del equipo multidisciplinar más los padres del niño (48,8%). El 51,1% de las enfermeras opinan que se realiza por consenso de los médicos más los padres y el 65,5% afirma que nunca les consultan en la toma de decisiones de pacientes a su cargo. Al 75% de los médicos siempre o casi siempre les consultan. El 57% de las enfermeras y el 83% de los médicos se sienten capacitados para la toma de decisiones sobre AET. El 77,2% de los profesionales cree que la adecuación se aplica en menos ocasiones de las necesarias.

ConclusionesExisten diferencias entre médicos y enfermeras tanto en la percepción del modelo de toma de decisiones como en el modo de actuación. Los profesionales no siguen ningún protocolo ni circuito de toma de decisiones consensuado.

What is known/what does this paper contribute?

The suitability of therapeutic effort is a difficult decision which is increasingly frequently made in paediatric intensive care units. These decisions generate conflicts amongst multidisciplinary teams, with professionals having doubts about whether accurate and timely action was undertaken. Obvious doubt is an all too common issue when the new ethical questions proposed by health-applied technology are responded to.

Few paediatric studies have been undertaken on real clinical practice and new studies are needed to probe into these complex decisions and into what acceptable limits of clinical practice would be. This study wishes to reflect the opinion and attitude of professionals involved in paediatric intensive care unit care, since greater knowledge of the actual reality will help to define the best possible guideline for action. In turn, this would improve the algorithm when taking decisions on the suitability of therapeutic effort for our young patients.

Study implications

In the light of findings and evidence, new lines of investigation needed to be developed to probe into these complex decisions, and greater post-graduate training to help improve the communication strategies of doctors and nurses. Better awareness of reality would help to define the best possible guideline, thus leading to improvement in decision-making for our patients and increasing the safety of our daily work. Our aim was to avoid any possible suffering for our young patients and their families.

Suitability of therapeutic effort (STE) is defined as the clinical decision to not initiate or to terminate life support measures when an imbalance is perceived to exist between them and their goals, the aim being not to fall into unreasonable therapeutic obstinacy.1,2 Suitability does not appear to be a new attitude, since in one way or another, efforts have been made suitable in certain situations, with the decision being taken singularly by the doctors and generally with them informing the parents of the non-viability of the child or simply informing them of the child’s death. Nowadays, good clinical practice essentially involves consensus between both parties, with respect for the principle of beneficence and for patient autonomy or autonomy of their family members. We are living at a time when STE is regarded for what it is, another decision to be made in critical care which, since at least a decade ago, has been made in our environment.2,3

In paediatrics, STE basically responds to two criteria: poor life prognosis or survival and poor quality of life, with the former being more frequently the cause of the latter.4 This means that the decision not to initiate or to terminate treatments may occur in two difference scenarios: that of trying to prevent relentless suffering and that of preventing very poor quality of life.2,5 Formally, one has to work in a team and at least the basic doctor/nurse duality should not come under question. STE decisions may be controversial and on occasions, conflicts are raised. This is because in these cases the technical decision is usually made by the doctor, but putting it into practice usually falls to the nurse. This situation can and normally does lead to conflicts within the multidisciplinary teams.6–8

The main aim of this study was to determine the opinion of professionals working in the paediatric intensive care units (PICU) of four hospitals in the Community of Madrid on STE, and to describe the professionals’ attitude to STE, stratifying them by professional category. We thus aimed to discover the reality about the STE from the actual professionals’ viewpoint, who could provide a practical bio-ethical care contribution. Bioethics assesses human problems arising in our daily work, helps the professionals to reflect on them and seeks an appropriate solution. It invites critical reflection on the way in which they are acting whilst executing their profession and helps to rectify this to improve patient care quality.

MethodA multicentre, cross-sectional, observational study in the PICU of four tertiary level hospitals in the Community of Madrid was conducted. These units were selected because of the greater probability of them carrying out STE for the type of patients they cared for, compared with the other hospitals in the Community of Madrid.

The study sample were PICU doctors and nurses, including residents of both professional categories. Inclusion criteria were that the professionals had to have worked for over a year in any of the study units. Exclusion criteria were that the professionals completed under 60% of the questionnaire or did not choose to participate in the study. The whole population was studied, which comprised 233 professionals.

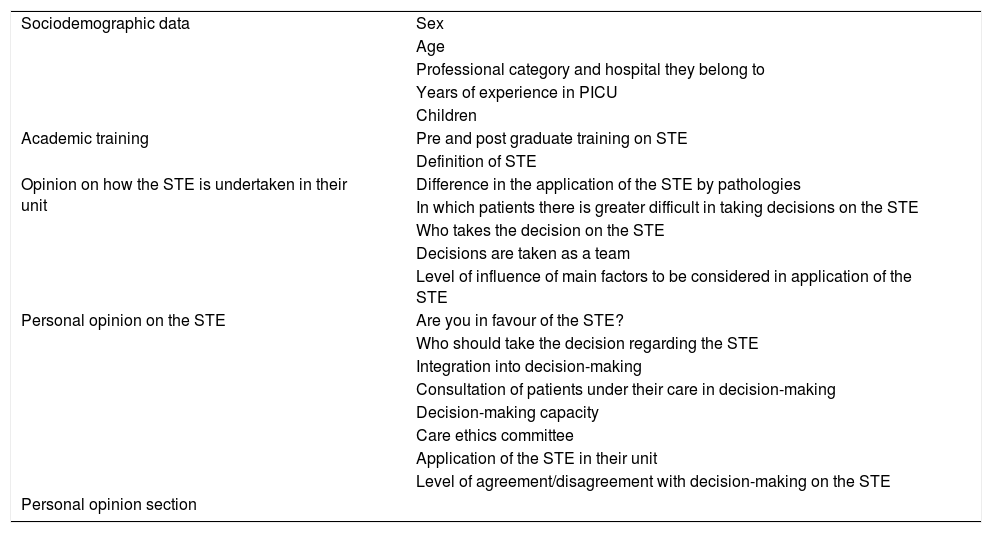

Information sessions were made on the study, where information was provided on the objectives, methodology and treatment of participant data. After these information meetings, participants were requested to give their informed consent. Since a validated questionnaire adjusted to study needs was not found, one was designed, using the three-round Delphi method. A group of doctors (5) and nurses (8) who were experts in PICU and in bio-ethical committees was brought together and asked to propose questions to explore the required fields. The research team met and summarized the proposals and returned them to the group of experts for their consensus, incorporated the changes and returned them for a third time for final agreement. A pilot study was conducted in the first ten individuals of the sample, with no difficulty being found in use. The studied variables were divided into sociodemographics; professional training; opinion on how to undertake STE in their unit; opinion on STE and a free section for their personal opinion. The variables studied in the questionnaire are contained in Table 1.

Variables studied in the questionnaire given to the professionals taking part in the study.

| Sociodemographic data | Sex |

| Age | |

| Professional category and hospital they belong to | |

| Years of experience in PICU | |

| Children | |

| Academic training | Pre and post graduate training on STE |

| Definition of STE | |

| Opinion on how the STE is undertaken in their unit | Difference in the application of the STE by pathologies |

| In which patients there is greater difficult in taking decisions on the STE | |

| Who takes the decision on the STE | |

| Decisions are taken as a team | |

| Level of influence of main factors to be considered in application of the STE | |

| Personal opinion on the STE | Are you in favour of the STE? |

| Who should take the decision regarding the STE | |

| Integration into decision-making | |

| Consultation of patients under their care in decision-making | |

| Decision-making capacity | |

| Care ethics committee | |

| Application of the STE in their unit | |

| Level of agreement/disagreement with decision-making on the STE | |

| Personal opinion section | |

A sealed box was set up at the nursing station of each unit so that, once the questionnaire had been completed, it could be deposited anonymously. Only the main researcher (MR) and collaborating researchers had access to the sealed box. After 14 days a reminder was sent to the professionals and after one month the questionnaires were collected. Data collection was made in October 2014. Approval for the project was requested and obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committees (CEIC for its initials in Spanish) of the different hospitals, and from the people in charge of each centre and each unit involved. Voluntary participation implied that the participants expressed their understanding and gave their written consent after receiving sufficient information on the nature of the study. The treatment, communication and ceding of personal data of all participants complied with that laid down in Organic Law 15/1999, of 13th December, governing personal data protection. In accordance with that established by this legislation, participants could exercise their rights of access, modification, opposition, and cancellation of data, and were to address the study MR for this end. In compliance with prevailing legislation (Law 14/2007), data were treated with absolute confidentiality, so that it was impossible to associate the study findings with the participants. Only the study MR had access to the personal data. The participants always had the contact telephone number and electronic mail address of the MR.

Responses were recorded in a database, and the SPPS 21.0 programme was used for analysis.

A global, descriptive analysis was used for all the variables studied in the professional population. The variables were described and compared between categories. Frequencies and percentages for the qualitative variables were used for this and the chi square test to compare whether there were any significant differences between the two professional categories studied. In the unit analysis the ANOVA t-test was used to compare quantitative/qualitative variables, the chi square test if the two variables were qualitative with normal distribution, the Kruskal Wallis and Mann Whitney U test, and the Fischer exact test if the distribution of the variables was not asymmetrical.

A .05 significance level was used for all analyses.

ResultsOverall descriptive resultsA total of 233 questionnaires were distributed, which represented the population of nurses and doctors in the four participant hospitals of the project. The number of duly completed questionnaires collected was 180 (77.2%).

The overall response rate, by professional category, was 139 (77.2%) nurses and 41 (20.8%) doctors. One hundred and forty-five women (80.6%) and 35 (19.4%) men participated. Sixty-five (36.1%) of the professionals had children, compared with 115 (65%) who did not. The mean age of the professionals was 36.29 (SD: 8.8) and they had a mean of 9.1 (SD: 7.3) years of experience in the PICU.

They number of professionals who declared they had been given no type of training on STE was 130 (70.6%), compared with 50 (27.8%) who said they had. Of the latter, 3 (1.7%) had training through a university master’s course, 15 (8.3%) through courses and 32 (17.7%) through seminars on the subject.

Regarding the correct definition of STE, being understood as “the clinical decision to not initiate or to terminate life support measures when an imbalance is perceived to exist between them and their goals”, 144 (80%) of professionals selected the correct answer.

To determine the professionals’ opinion and attitude, they were asked whether the patient’s medical diagnosis had an impact on their decision to undertake a STE: 85 (47.2%) professionals said it did, 77 (42.8%) said they found no difference between the patients with different pathologies and 18 (10%) stated they would not be able to assess this.

The participant professionals classified types of patients according to the difficulty involved in reaching the decision of the STE: 64 (38.5%) declared they had difficulty in all patients, regardless of their diagnosis, 27 (16.2%) had difficulty in oncology patients and 16 (9.6%) in patients with extracorporeal membranous oxygenation (ECMO).

The number of professionals who stated they were in favour of the STE was 178 (98.9%); none declared to not be in favour and 2 (1.1%) declared they would not know how to assess this question.

Regarding the question of who the professionals thought usually take the decision on STE, 80 (44.4%) professionals stated the decision was taken by the doctors and parents of the child, followed by 72 (40%) who thought the decision was taken by medical consensus.

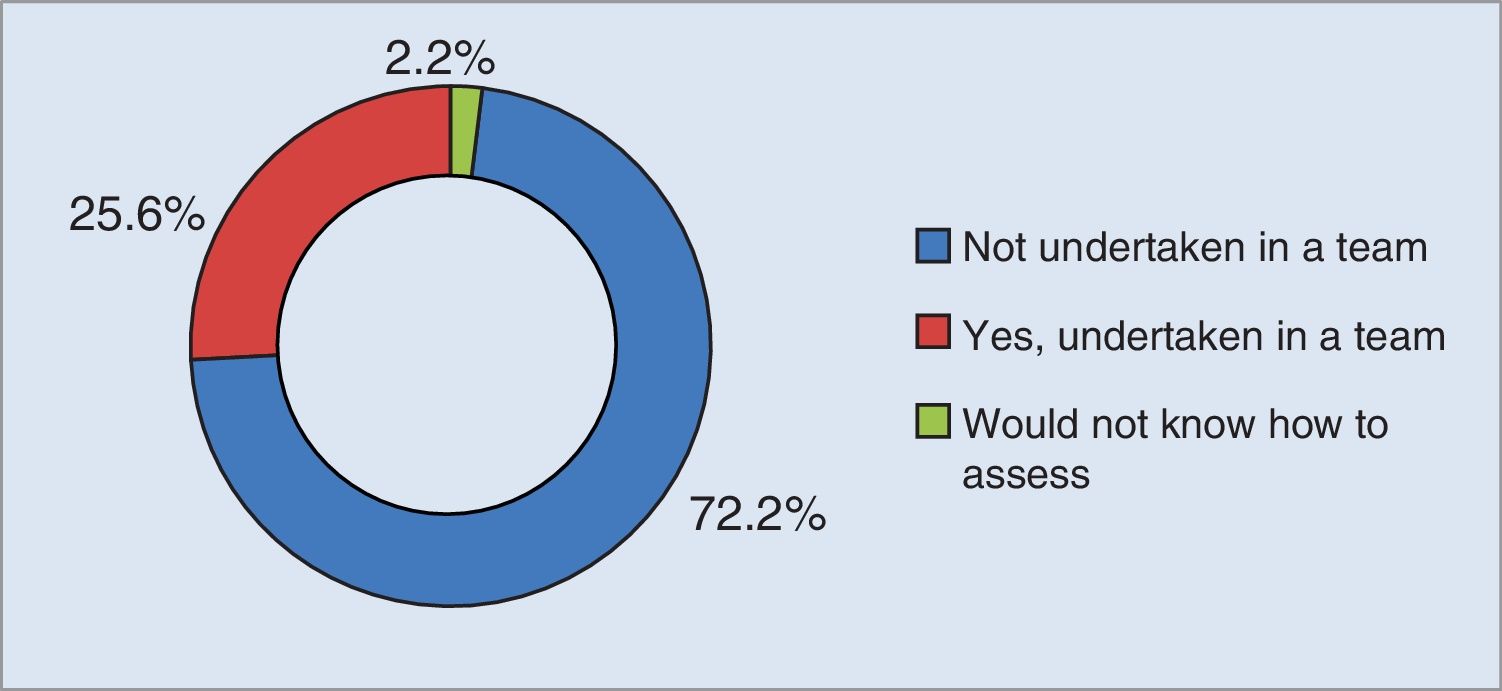

Regarding whether decision-making about patients was made by a team, 130 (72.2%) professionals stated that when decisions were taken not all members of the multidisciplinary team were taken into consideration (Fig. 1).

Regarding the intervention of the ethical care committee on decision-making on STE, 70 (38.9%) stated that it should participate in decision-making, 33 (18.3%) that it should not participate and 76 (42.2%) stated they would not be able to assess this.

In the personal opinion on STE section, 63 (35%) professionals stated that parents had little say in decision-making on STE, with all the hospitals studied coinciding in this. Among the professionals, 129 (55.3%) highlighted that the parents should participate in decision-making with the multidisciplinary team, and that this should be accurately carried out in time and form. The professionals reflected on the difficulty they had in taking decisions on STE due to the non-existence of any protocol or guidelines in any unit.

Results by professional categoryWhen analysing the difficulty professionals have in taking decisions on STE, the doctors had the greatest difficulty in taking decisions for oncology patients (9 [22%]), followed by cardiac patients (8 [19.5%]), with p > .05. The nurses (57 [41%]) had difficulty in all patients, regardless of their diagnosis, followed by cardiac patients (20 [14.4%]) and oncology patients (18 [12,9%]).

The doctors (20 [48.8%]) thought the decision was taken through agreement by the multidisciplinary team, with consideration of the child’s parents, compared with 71 (51.1%) nurses who thought the decision was taken by the team of doctors and the child’s parents. A total of 62 (44.6%) nurses stated that the decision was made only and exclusively by the doctors. Statistically significant differences existed.

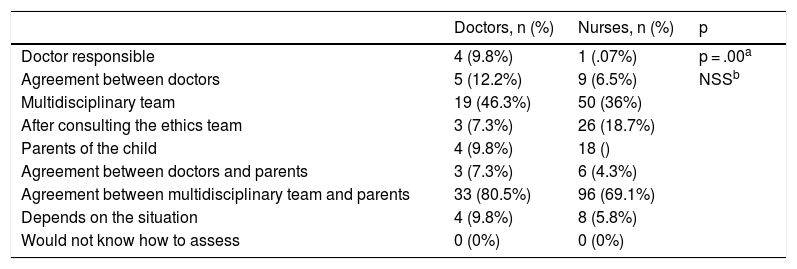

Both groups, with 33 (80.5%) doctors and 96 (69.1%) nurses, agreed that the decision should have been made only and exclusively by consensus from the multidisciplinary team, plus the child’s parents. (Table 2).

Opinion of the doctors and nurses on who should take the decision of the STE in the PICU.

| Doctors, n (%) | Nurses, n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor responsible | 4 (9.8%) | 1 (.07%) | p = .00a |

| Agreement between doctors | 5 (12.2%) | 9 (6.5%) | NSSb |

| Multidisciplinary team | 19 (46.3%) | 50 (36%) | |

| After consulting the ethics team | 3 (7.3%) | 26 (18.7%) | |

| Parents of the child | 4 (9.8%) | 18 () | |

| Agreement between doctors and parents | 3 (7.3%) | 6 (4.3%) | |

| Agreement between multidisciplinary team and parents | 33 (80.5%) | 96 (69.1%) | |

| Depends on the situation | 4 (9.8%) | 8 (5.8%) | |

| Would not know how to assess | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

All the doctor participants in the study (41 [100%]) stated they were in favour of STE. A total of 137 (98.6%) nurses were also, and 2 (1.4%) of them declared they would not know how to assess this question.

The doctors declared they felt involved in the decision-making of patients under their care always (17 [41.5%]) and almost always (14 [34.1%]). In contrast, 84 (60.4%) of nurses stated they never felt involved and 38 (27.3%) almost never (Table 3).

Perception of doctors and nurses on the degree of integration in decision-making on the STE of patients under their care.

| Doctors, n (%) | Nurses, n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Always | 17 (41.5%) | 0 (0%) | NSSa |

| Almost always | 14 (34.1%) | 4 (2.9%) | |

| Sometimes | 8 (19.5%) | 13 (9.4%) | |

| Almost never | 2 (4.9%) | 38 (27.3%) | |

| Never | 0 (0%) | 84 (60.4%) |

Regarding the reality of team participation in decision-making, 31 (75.6%) doctors declared they always participated in decision-making on STE of patient in their unit and 121 (87.1%) nurses stated they were never consulted nor participated in this decision-making about patients under their care.

Regarding the ability of doctors and nurses on decision-making of STE, 34 (82.9%) doctors felt capable of taking this type of decision, whilst 80 (57.6%) nurses felt capable of decisions on the STE and 42 (30.2%) declared they would not know how to assess this issue.

The doctors stated they were quite in agreement (19 [46.3%]) and in agreement (14 [34.1%]) about how the decisions were taken on STE in their unit. In contrast, 89 (64%) nurses declared they quite disagreed with how the decisions on STE were currently taken, 24 (17.3%) stated they agreed and 15 (10,8%) they quite agreed.

A total of 25 (61%) doctors and 114 (82%) nurses stated that the STE were applied in fewer occasions than was necessary in all the intensive care units under study (Fig. 2).

When asked about the most important factors to consider on applying STE in the PICU, the doctors and nurses of the four hospitals agreed that these were: the severity of the process, with a mean sore out of 10 of 8.23 (SD: 2.18); the possibility of response, with a mean score of 8.79 (SD: 1.85) out of 10, and the future quality of life of the paediatric patients, with a mean score out of 10 of 9.26 (SD: 1.48).

DiscussionAfter assessing the results, information was obtained about determining the opinion of the professionals on the application of the STE and describing their attitude towards STE, which is a positive attitude in that both professional categories are united in good patient care. In the decision-making process analysis, it was found that 40% of professionals said the decision was only and exclusively taken by the doctor without considering the child’s parents or the rest of the care team. This data was also found in several studies, where it was reflected that the technical decision is usually medical but that its execution usually corresponded to the nursing team, which generally led to conflicts in the decisions taken by the team.6,9

It was observed that there was a large difference between doctors and nurses regarding the perception on participation and the way in which decision-making was made, and that this could be linked with multiple studies where two teams of professionals had a different vision from the person who usually took the decision.2,10 This could be one of the reasons for the ethical conflicts relating to what criteria are used and what criteria should be used for taking this type of decision.3,7–9

Another major point where there was agreement amongst professionals was in the importance of participation from parents in decision-making, without the weight of it falling on them. 80.5% of doctors and 69.1% of nurses were of the opinion that the parents had to form part of the STE decision and it was the professionals who had to make a real effort to provide the parents with the necessary and appropriate information, bearing in mind the pain and suffering of the circumstances, together with the person’s confused state and their personal beliefs. The child’s best interest had to always be intricately linked to the parents’ best interest.8,10,11

During this study, the professionals reflected that parent participation is increasingly greater and they are considered increasingly more, albeit late. Participation from parents in decision-making is not just an ethical and legal duty of professional team, but an ethical and legal right of the patient. It is essential to bear in mind that the involvement of the parents in decision-making must always be based on true, complete, and comprehensible information being made available to them.2–4,6–8,10,12

By analysing what team members were involved in the decision, 44.4% of the professionals declared that the decision is taken by the doctors and the child’s parents. This statement has been reinforced by several authors,4,13,14 but others6,7,15,16 demand participation from the nursing team, as expressed by 55.3% of the participants in this study.

The literature reflects that the nurses offer support with a humanistic vision of care.6,7,17,18 They are the bedside staff and those who continuously offer support to the families. They are qualified and increasingly more trained personnel, and their participation in these matters would therefore be enriching and essential if the necessary consensus was taken into account in decision-making on STE for good clinical practice.10,17,18 The reality is different, since 60.4% of the nurses never felt involved in the decision taken regarding patients under their care. The exclusion of the nurse from involvement in this decision-making could lead to frustration, tension and imbalance in the care team, together with lack of understanding and difficulty in carrying out care.6 Several authors report that the estimation of the prognosis made by the family or the nurses is much more in keeping with reality than that made by the doctors, and it is therefore important to consider them.4,7,16,17

Regarding training for the ability of decision-making for patients under their care, 63,3% of the professionals felt they had training whilst 76.6% felt they had no training relating to STE. This reflects that the professionals assume ability comes from experience and not from training.6,19–22

Over 80% of the professionals believed that decision-making on STE was made on fewer occasions than necessary. The lack of decision-making could be because the STE is a complex decision involving many values and the doubt always remains whether something further could have been done for the patient or what their life would have been like if different techniques or forms of care had been used.3,5,15,18 The professionals did not only think the decisions were taken on fewer occasions than necessary but that the decision was taken too late. This delayed decision increased the suffering and pain of the child and their parents, and the impotence of the staff charged with their care, incapable of responding to the needs demanded of them.11,14

Most professionals did not much agree with the way in which the decisions on STE were taken in their unit, with the percentage being much higher in nurses. This percentage could be related to the low involvement of nurses in the team when decisions were taken about patients under their care and to the opinion that decisions were not taken as a team. The most outstanding factor of this study is that the opinions and beliefs conveyed by the respondents were in keeping with that described in other care and cultural environments and meant that measures of improvement could be put into practice which could affect the humanisation and quality of care of end-of-life paediatric patients.4,6,7,16,19

Possible study limitations were the response rate of the doctors which was 41 (67.2%), lower than that of the nurses, which was 139 (80.8%), despite the fact that in both cases a double-round collection was made. To minimize the impact of use the questionnaire was designed with the Delphi group methodology with contributions from experts on STE and a pilot study prior to its distribution.

ConclusionsThe study professionals from the four PICU of hospitals in the Community of Madrid demonstrated a high level of experience and knowledge of the STE, despite having received practically no regulated training on this issue.

Several outstanding differences existed between doctors and nurses, not just in their perception of the decision-making model, but in the different way the two professional categories declared they acted when faced with the STE. There were no protocols or guidelines for taking consensual decisions in any of the PICU studied, with clearly different criteria even being found between professionals.

It may be highlighted that the attitude of the professionals of both categories is that they are united in their concern for good patient care. New lines of work should be created with greater involvement and participation from the whole multidisciplinary team, and particularly from the nursing team, which is demanding greater participation in decision-making on STE. Following assessment of the results obtained and greater awareness of the reality in the different PICU, it is important to use protocols to classify patients according to their possibilities of recovery and to act as a guide in decision-making, but one which never ignores individual case analysis.

In the light of the results and the literature studied, new lines of investigation must be studied to explore further into these complex decisions. Further post-graduate training is required to improve the communication strategies of doctors and nurses. Greater awareness of reality would help to define the best action possible, thus improving the way in which decisions are made for end-of-life paediatric patients.

FinancingThe authors declare they did not receive any subsidies, grants, or financial support for the undertaking of this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

To all the professionals who participated in this study, because without them this project would not have been possible.

Please cite this article as: López-Sánchez R, Jiménez-García E, Osorio-Álvarez S, Riestra-Rodríguez MR, Oltra-Rodríguez E, García-Pozo AM. Adecuación del esfuerzo terapéutico en unidades de cuidados intensivos pediátricos: opinión y actitud de los profesionales. Enferm Intensiva. 2020;31:184–191.