To understand for what care of the patient at the end of life and their relatives means to ICU health professionals.

MethodsQualitative study with a Research-Action (AI) design, in two intensive care units of the city of Bogotá. Groups were formed in each unit and each group included at least six health professionals, the data collection techniques were: 4 participative assemblies and 6 clinical narratives, the data analysis was done through the preparation of the data, discovery of topics, coding and interpretation of data, relativisation and rigour of the data.

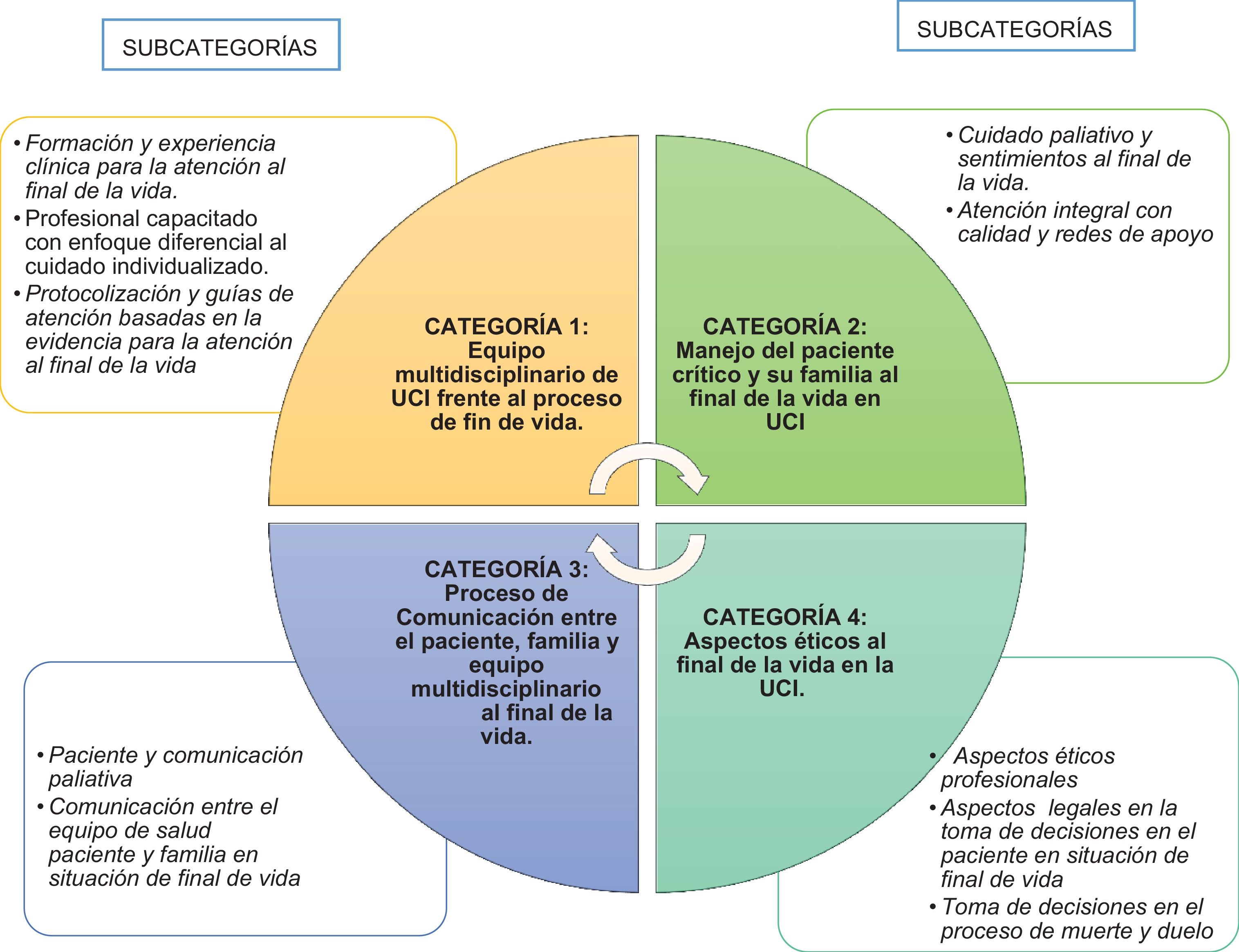

Results20 ICU workers participated, the analysis of the data revealed four thematic categories: Multidisciplinary team of the ICU facing the end-of-life process, Management of critical patients and their families at the end of life in the ICU, Communication process between the patient, family and multidisciplinary team at the end of life, Ethical aspects at the end of life in the ICU

ConclusionsThe professionals consider preserving quality of life during the patient's stay in the ICU a therapeutic objective. The development of evidence-based guidelines that facilitate multidisciplinary management at the end of life, customisation of care, effective communication, fulfilling the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of the person and their family and favouring the patient’s right of autonomy in decision making.

Comprender el sentido otorgado por los profesionales de la salud de la Unidad de Cuidado Intensivo (UCI), respecto a los cuidados del paciente al final de la vida, y de sus familiares.

MétodosEstudio cualitativo con un diseño Investigación-Acción (IA), en dos UCIs de la ciudad de Bogotá. Se formó un grupo en cada unidad, cada uno incluyó mínimo seis trabajadores de la salud. Las técnicas de recogida de datos fueron: 4 Asambleas participativas y 6 narrativas clínicas. El análisis de datos incluyó la preparación de los datos, descubrimiento de temas, codificación e interpretación de datos, relativización y rigor de los datos.

ResultadosParticiparon 20 trabajadores de UCI, del análisis de los datos emergieron cuatro categorías: Equipo multidisciplinario de UCI frente al proceso de fin de vida, Manejo del paciente crítico y de su familia, al final de la vida en UCI, Proceso de Comunicación entre el paciente, familia y equipo multidisciplinario al final de la vida, Aspectos éticos al final de la vida en la UCI.

ConclusionesLos profesionales conciben como un objetivo terapéutico, preservar la calidad de vida durante la estancia del paciente en UCI. Para el personal de salud, es fundamental desarrollar guías basadas en la evidencia que faciliten el manejo multidisciplinar al final de la vida, la personalización de la atención, la comunicación efectiva, la satisfacción de las necesidades físicas, emocionales y espirituales de la persona y su familiar y favorecer el derecho de autonomía del paciente en la toma de decisiones.

What is known?

Death is a reality that often occurs in Intensive Care Units. This phenomenon is complex because the ICU is not the best place to die, given that the patient and the family find themselves in a situation of uncertainty, vulnerability, pain, loneliness, depression and suffering.

What does this paper contribute?

To reduce the uncertainty, vulnerability, pain, loneliness, depression and suffering, the professionals propose identifying and implementing evaluation tools for the patient and family’s emotional and spiritual needs, in the daily practice of the physicians and nurses. Another strategy for improvement that they propose is making advance directives explicit with the relatives and giving priority to the directives in agreement with the family, to make end-of-life decisions.

Death is a reality that often occurs in Intensive Care Units (ICUs).1 This phenomenon increases its complexity because the ICU is not the best place to die. There, the patient and the family find themselves in a situation of uncertainty, vulnerability, pain, loneliness, depression and suffering. A great many patients in the ICU have inadequate symptom control, the expectations and needs of the relatives are not achieved, communication between hospital personnel and the relatives is deficient, there is an overload in treatment cost for some families and not all personnel are prepared to offer end-of-life care.2,3 This reality can be seen in a qualitative study carried out in an ICU in Bogotá (Colombia), which describes how individuals, sedated or confused, remain excluded from decision making, while the setting of the ICU is defined by the relatives as a space in which death, pain and suffering are frequent.4

Although decision making should be shared among the team of professionals, the patient and family, most of the time it is the physician that makes the decisions.1 A multi-centre study carried out in Spain indicated that the decision arose from the physicians in 83.8% of the cases, was proposed by family members in 13.5%, and ensued from both parties (family members and physicians) 2.7% of the time.5 In addition, there are few studies that show the preferences of the patients with regard to their death; it is possible that respecting patients’ wishes would reduce over-zealous therapy, so healthcare should feature greater patient participation in decision making and, to do so, patients must be better informed about the prognosis of their diseases.6

The perception of health personnel of care at the end of life reveals that the nurses consider that physicians avoid addressing the subject of death with their patients, more than they admit.7 Nurses also perceive that they do not actively participate in decision making, although they contribute to the process,8 and they emphasise that nurses have greater direct contact with patients.9

In Colombia, the scientific literature search did not yield any explicit initiatives about end-of-life care in the ICU. Specialists in palliative care are limited, as are training programmes in this area. Consequently, ICU health personnel need to strengthen the skills needed to offer comprehensive end-of-life care. In the Colombian legal framework, Resolution 1216 (2015) establishes the directives for the organisation and functioning of the Committees that put into effect the right to die with dignity and governs the right to palliative care that improves quality of life for the patient and the family, focused on comprehensive pain treatment and relief from suffering and from psychological, emotional, social and spiritual aspects of it, as well as the right to voluntarily and in advance to cease unnecessary medical treatment that does not represent dignity of life for the patient.10

Health personnel should promote a “good death'', emphasising family companionship and relief from suffering, so that the patient feels that the surroundings in this situation are peaceful at the last moment of life.11–13 However, although there is a legal framework that regulates the right to die with dignity, the health personnel do not always embody this in their daily practice, due to the influence of their deeply rooted knowledge, values and beliefs about death and end-of-life care. The study by Vicesi5 that analysed the bioethical concerns about the process of dying from the point of view of intensive care health professionals, revealed the difficulties experienced by the professionals, which stem from training that is not very humanised and is a bit detached from the process of dying as a part of life.

Promoting actions that favour a “good death'' in these care units is not easy. Consequently, over the last decade interest in studying how patient care can be improved in the end-of-life process.14 A few of the components described in the literature include the following: good communication skills among the members of the multidisciplinary team and the family/patient, excellence in evaluating and managing symptoms, a healthcare focus emphasising the patients, their values and treatment preferences, healthcare centred on the family, and regular multidisciplinary meetings.15

Based on what has previously been indicated in this article to promote aimed at improving processes of change to end-of-life care in the ICU, knowing the perspective of the professionals about their daily practices is essential. That is the reason why the objective of this study was to understand the meaning that ICU health personnel gave with respect to the end-of-life patient and family members. Bearing in mind that there are few qualitative studies about the issue in Colombia, the relevant aspects explored from the perspective of the subjects, all of them important in strengthening knowledge in this field and transferring it to clinical practice, are as follows: communication skills, managing symptoms, decision making and end-of-life ethical problems.

MethodDesignA qualitative method with a Research-Action (RA) design was used; as a reference we took what had been proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart,16 who described the participative nature focused on having individuals improved their own practices as being among the methods main features. The RA process occurs through a series of steps included in a spiral of self-reflexive cycles consisting of 3 stages: 1. Analysis of the reality, 2. Planning and implementation of the action, and 3. Evaluation of the action.17 This study presents results from the first stage of the RA programme, which attempted to analyse the social reality collectively and to raise the awareness of the health personnel about end-of-life care in the ICU and how pertinent the approach to it was.

SettingThe study was carried out in 2 ICUs in highly complex hospitals in Bogotá (Columbia), after authorisation by the institutions. The ICU directors and the unit nurse coordinators participated actively; the nurse coordinators convoked the health personnel. One of the ICUs is a polyvalent unit consisting of 16 beds divided into 2 areas (9 coronary unit beds and 7 step-down unit beds) caring for patients with surgical and medical pathologies. The other ICU, likewise polyvalent, consists of 21 beds.

SubjectsThe group was the analysis unit, not the individual. Each group included health personnel from various disciplines. Convenience sampling was performed, bearing in mind the inclusion criteria: a) a minimum of 6 months of experience working in the ICU, and b) voluntary participation. The distribution of groups with respect to the number of participants was the same in both ICUs. The ICU1 group included 10 professionals or technicians: medicine (n = 3), nursing (n = 2), physiotherapy (n = 1), respiratory therapy (n = 1) and assistant nursing technicians (n = 3). The ICU2 group also consisted of 10 professionals or technicians: medicine (n = 2), nursing (n = 2), nutrition (n = 1), respiratory therapy (n = 1), physiotherapy (n = 1) and assistant nursing technicians (n = 3). As criteria of heterogeneity, the following variables were established: sex, profession, length of ICU experience and level of training. Relative heterogeneity was sought in group composition to achieve the greatest diversity of health personnel perspectives. Given the multidisciplinary focus of the study, at least 1 representative of the basic team working in the ICU was involved. Length of ICU experience and training level were conceived as important variables that diversified the knowledge, attitudes and practices of the health personnel and provided better understanding of the end-of-life phenomenon in the ICU.

Dimensions of the phenomenonThe following dimensions of exploratory character were considered: communication skills, symptom management, decision making and end-of-life ethical issues.

Data collectionThe process of collecting the information aimed at the first phase of the RA programme, analysis of the reality (Field survey), was carried out. Two data collection techniques were used to do so:

Participative Assemblies: 4 assemblies lasting approximately an hour, 2 in each ICU, were carried out. The objective of this technique was to self-evaluate the good practices of end-of-life care in the ICUs, with reference to the quality standards proposed by the Spanish project HU-CI (Humanising Intensive Care):18 protocols for end-of-life care, support for physical symptoms, companionship in end-of-life situations, limitation of life-sustaining treatment (LST), and multidisciplinary involvement in deciding and developing measures of limiting LST.

Narratives: 6 professionals belonging to the basic ICU team, who had participated in the assemblies, prepared narratives that described their usual clinical practice when faced with decision making and end-of-life care in the ICU: Medicine (n = 1), Nursing (n = 2), Physiotherapy (n = 1) and Assistant nursing technicians (n = 2). As a heterogeneity criterion, the variables considered were: profession, length of ICU experience and level of training. The narratives were written, with a minimum length of 1800 words and a maximum of 2500 words; to guide the narrative writers, they were given an example of the structure of a narrative published in the online journal “Memory Files” (“Archivos de la memoria”).19

Data analysisThe research team carried out the data analysis, following the analysis proposal of Taylor and Bogdan, adapted by Amezcua and Gálvez, which includes a spiral scheme that makes it necessary to roll back the data again and again to give the interpretations consistency:20

- a)

Preparing data: the 4 participative assemblies and 6 narratives were transcribed and reviewed, and then studied carefully.

- b)

Finding themes: the topic areas on which the participative assemblies and the narratives were based were identified.

- c)

Codifying and interpreting data: the information obtained was classified, analytical categories were developed and the coding was carried out on the basis of the recurrent topics and the specific objectives of the study.

- d)

Making the data relative and ensuring rigor: each researcher analysed the data (the participative assemblies and narratives) individually and then the data was triangulated among the researchers.

This study, in agreement with Article 11 of Resolution 8430 (1993) in Colombia, was considered to be of minimum risk for the life and integrity of the research subjects. Participation was voluntary and the participants gave signed informed consent. This project was approved by the committee for ethics in research on human beings (CEISH is the Spanish acronym) on 22 February 2018 in the city of Bogotá. From the point of view of subject integrity, the autonomy, confidentiality, privacy, veracity and justice were preserved.

ResultsThe results are shown with the sociodemographic data and the description of the emerging categories.

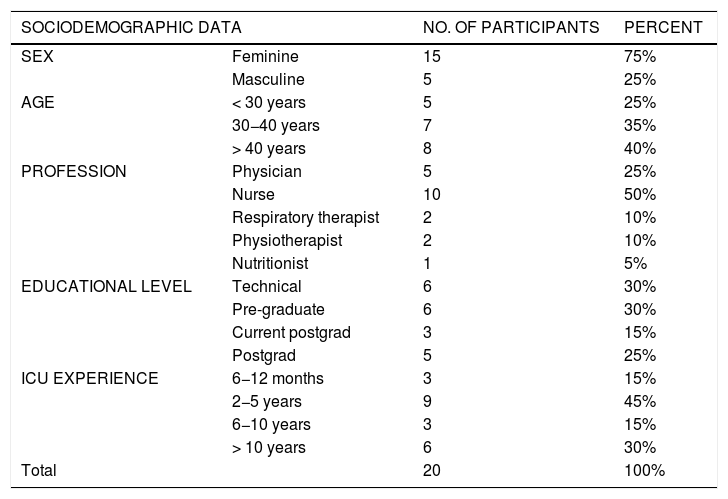

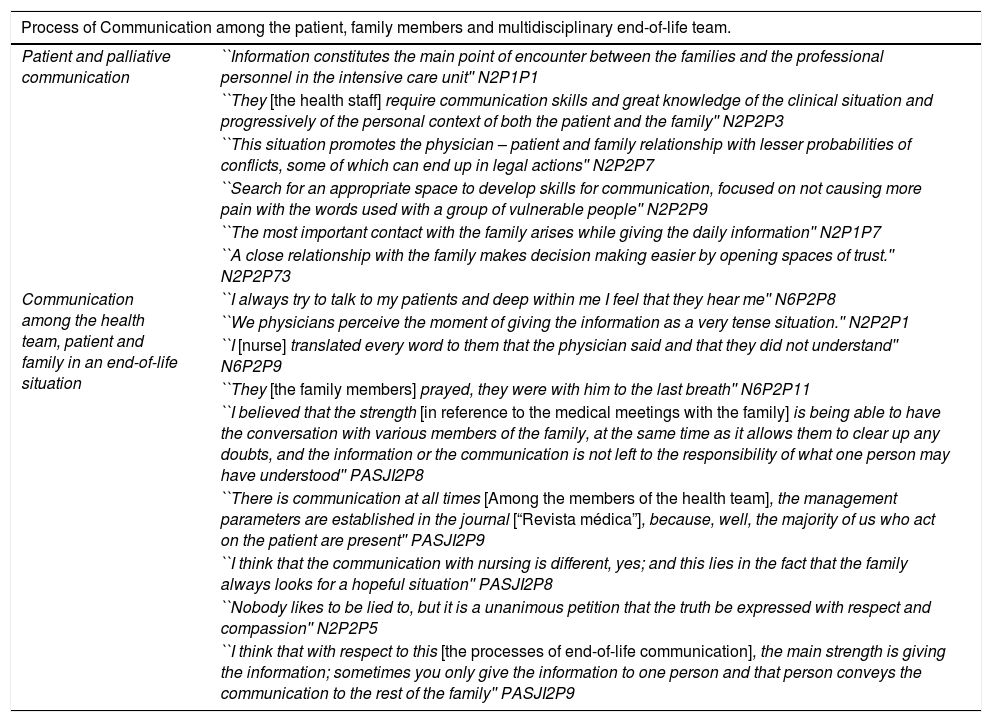

Sociodemographic dataTwenty people participated, 75% were of the feminine sex and the predominant age range was > 40 years (40%). The length of ICU experience reported by 45% of the participants was 2−5 years. As for the level of education, 30% had a technical profile; 30%, pre-graduate training; 25%, specialisation; and 15% were physicians carrying out ICU specialisation (Table 1).

Sociodemographic data.

| SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC DATA | NO. OF PARTICIPANTS | PERCENT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEX | Feminine | 15 | 75% |

| Masculine | 5 | 25% | |

| AGE | < 30 years | 5 | 25% |

| 30−40 years | 7 | 35% | |

| > 40 years | 8 | 40% | |

| PROFESSION | Physician | 5 | 25% |

| Nurse | 10 | 50% | |

| Respiratory therapist | 2 | 10% | |

| Physiotherapist | 2 | 10% | |

| Nutritionist | 1 | 5% | |

| EDUCATIONAL LEVEL | Technical | 6 | 30% |

| Pre-graduate | 6 | 30% | |

| Current postgrad | 3 | 15% | |

| Postgrad | 5 | 25% | |

| ICU EXPERIENCE | 6−12 months | 3 | 15% |

| 2−5 years | 9 | 45% | |

| 6−10 years | 3 | 15% | |

| > 10 years | 6 | 30% | |

| Total | 20 | 100% | |

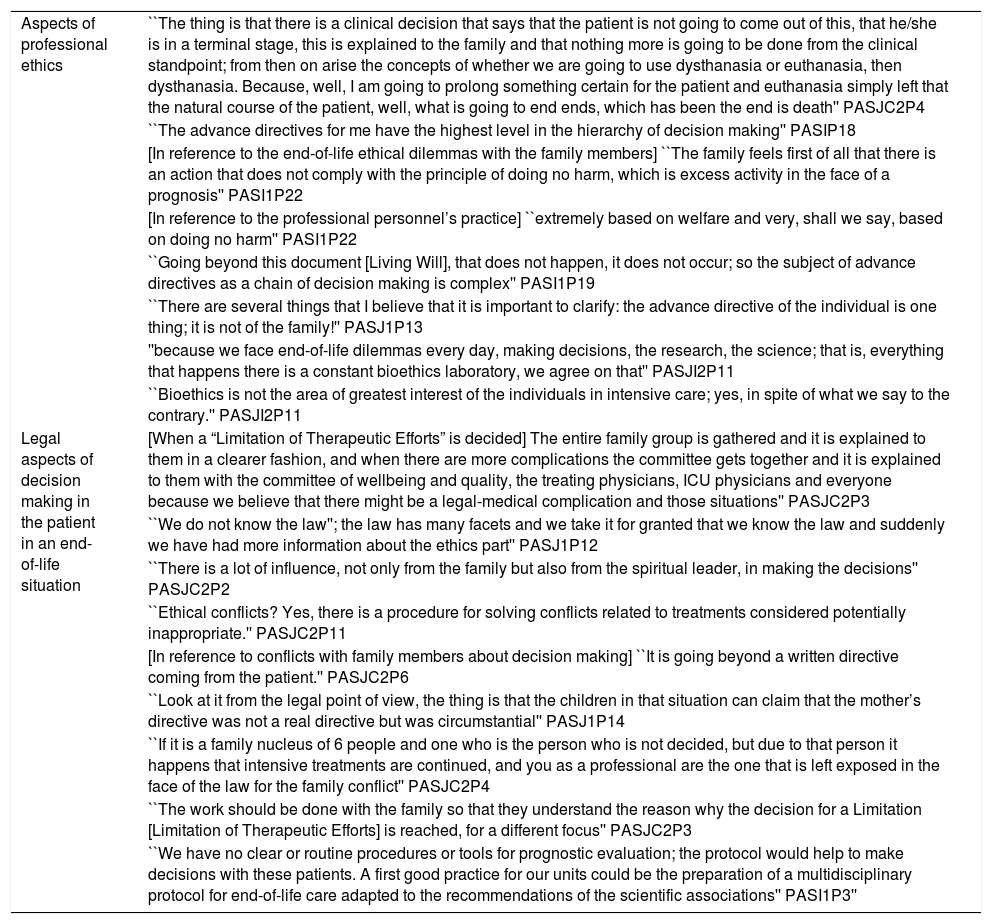

Based on the information obtained from the participative assemblies and the narratives, the perceptions of the professionals working in the ICU as to end-of-life care were identified. Content analysis yielded 4 categories, which are shown in Fig. 1. These categories are also described below:

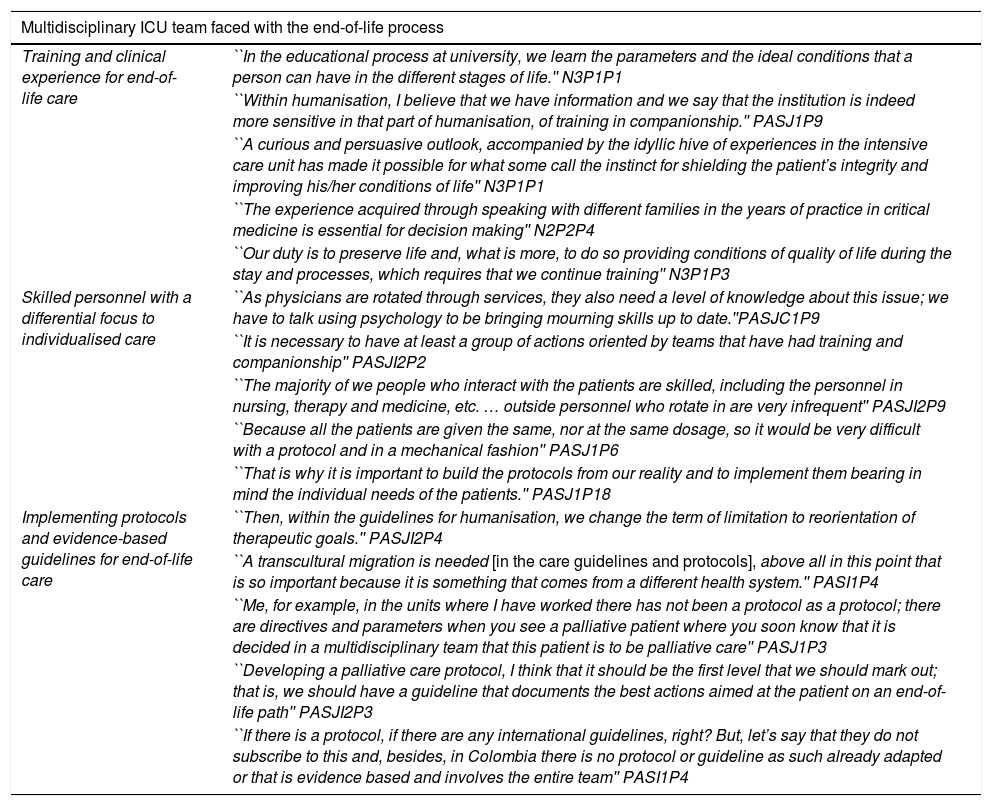

Multidisciplinary ICU team in the face of the end-of-life processThis category describes the group of professionals from different disciplines and having different techniques, who performed a set of practices with skill and vocation aimed at decision making, in order to treat or less the physical, emotional or spiritual symptoms in patients in end-of-life situation and their families. Among the findings, it was revealed that not only did the basic ICU team of professionals (Medicine, Nursing, Physiotherapy and Nursing aides) work together, the team also worked with other professionals that added to the wellbeing of the patient and family: respiratory therapists, psychologists, nutritionists and palliative care team. Three subcategories were defined for this category, described below. The relevant narratives that characterised this category are included in Table 2.

Relevant Category 1 data.

| Multidisciplinary ICU team faced with the end-of-life process | |

|---|---|

| Training and clinical experience for end-of-life care | ``In the educational process at university, we learn the parameters and the ideal conditions that a person can have in the different stages of life.'' N3P1P1 |

| ``Within humanisation, I believe that we have information and we say that the institution is indeed more sensitive in that part of humanisation, of training in companionship.'' PASJ1P9 | |

| ``A curious and persuasive outlook, accompanied by the idyllic hive of experiences in the intensive care unit has made it possible for what some call the instinct for shielding the patient’s integrity and improving his/her conditions of life'' N3P1P1 | |

| ``The experience acquired through speaking with different families in the years of practice in critical medicine is essential for decision making'' N2P2P4 | |

| ``Our duty is to preserve life and, what is more, to do so providing conditions of quality of life during the stay and processes, which requires that we continue training'' N3P1P3 | |

| Skilled personnel with a differential focus to individualised care | ``As physicians are rotated through services, they also need a level of knowledge about this issue; we have to talk using psychology to be bringing mourning skills up to date.''PASJC1P9 |

| ``It is necessary to have at least a group of actions oriented by teams that have had training and companionship'' PASJI2P2 | |

| ``The majority of we people who interact with the patients are skilled, including the personnel in nursing, therapy and medicine, etc. … outside personnel who rotate in are very infrequent'' PASJI2P9 | |

| ``Because all the patients are given the same, nor at the same dosage, so it would be very difficult with a protocol and in a mechanical fashion'' PASJ1P6 | |

| ``That is why it is important to build the protocols from our reality and to implement them bearing in mind the individual needs of the patients.'' PASJ1P18 | |

| Implementing protocols and evidence-based guidelines for end-of-life care | ``Then, within the guidelines for humanisation, we change the term of limitation to reorientation of therapeutic goals.'' PASJI2P4 |

| ``A transcultural migration is needed [in the care guidelines and protocols], above all in this point that is so important because it is something that comes from a different health system.'' PASI1P4 | |

| ``Me, for example, in the units where I have worked there has not been a protocol as a protocol; there are directives and parameters when you see a palliative patient where you soon know that it is decided in a multidisciplinary team that this patient is to be palliative care'' PASJ1P3 | |

| ``Developing a palliative care protocol, I think that it should be the first level that we should mark out; that is, we should have a guideline that documents the best actions aimed at the patient on an end-of-life path'' PASJI2P3 | |

| ``If there is a protocol, if there are any international guidelines, right? But, let’s say that they do not subscribe to this and, besides, in Colombia there is no protocol or guideline as such already adapted or that is evidence based and involves the entire team'' PASI1P4 | |

Participative assembly (PA) and narrative (N), paragraph (P), Unit at Hospital San José (SJC), Unit at Hospital San José Infantil (SJI).

The knowledge obtained in pre-graduate training provides tools for facing a setting as difficult as the ICU is. However, postgraduate training and ongoing skill building are required; these, combined with experience, provide the professional expertise needed to handle this service and face the ethical dilemmas arising every day and to develop clinical leadership and critical thinking.

The health team working in the ICU experiences outcomes such as death every day, the result of caring for end-of-life patients. In spite of the fact that the personnel are trained to save lives, preserving quality of life during the patient’s stay is conceived as an important therapeutic objective.

Skilled professionals with a differential focus on individualised careThe personnel in the ICU trained for and skilled in giving care in these units. They have the experience to face the challenges of care practice and provide critical thinking for the palliative care of the patient. As for the care, the importance of offering companionship and humanised care to the end-of-life patient is stressed.

In taking care of the critical patient, it is important to bear in mind that the focus cannot be put solely on treatment and management. Consequently, it becomes more difficult to build and implement standardised protocols on the subject, because personalising care must be taken into consideration.

Evidence-based protocols and care guides for end-of-life careIt is important to modify the ICUs so that they become more humanised services, that have skilled personnel that prioritise comprehensive care, shared decision making, and resolutions for the frequent ethical dilemmas. Of similar importance is the preparation of documentation (protocols and guidelines) that provide evidence transferable to the ICU for end-of-life care and that is adapted to the Colombian laws and cultural context.

Caring for the patients and families in an end-of-life situation is a labour involving all the health personnel that work in the ICU; each one takes action with the patient, working as a team to provide comprehensive care. The development of guidelines that, in addition to being evidence-based, facilitate multidisciplinary attention is fundamental.

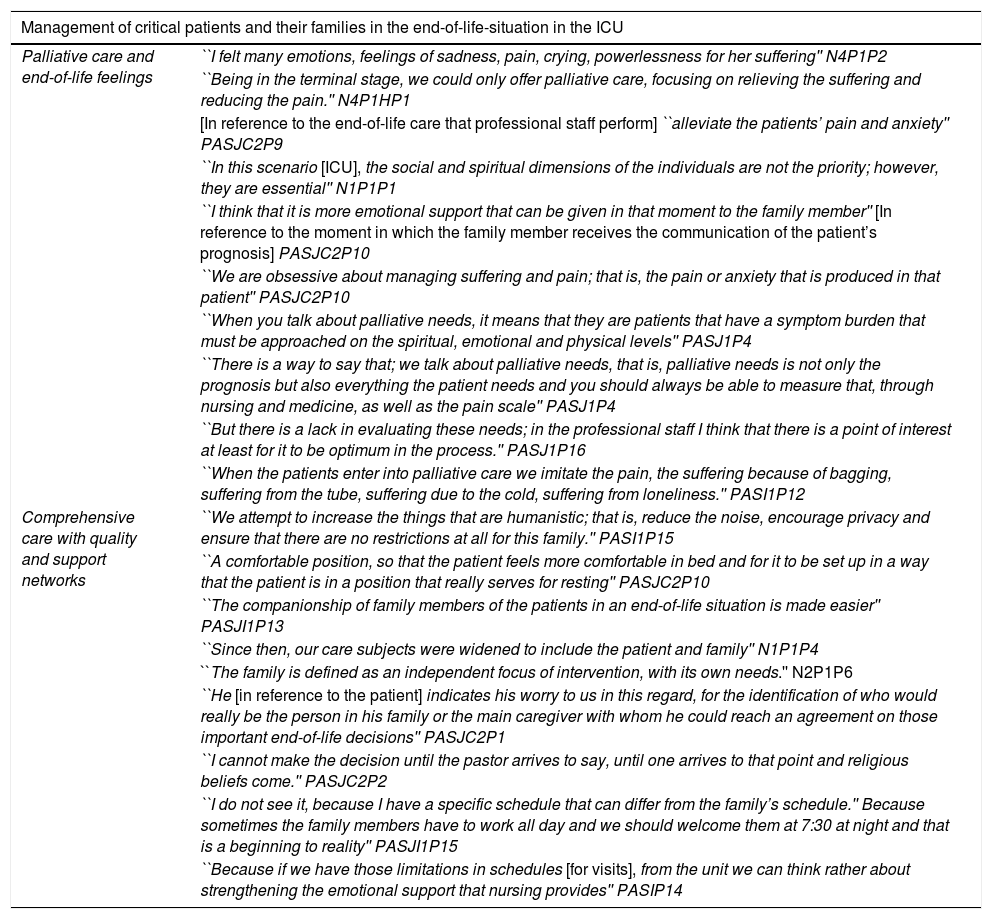

End-of-life management of the critical patient and his/her family in the ICUThis category covers the physical and emotional activities and interventions that the multidisciplinary team offer the patient in an end-of-life situation. The team’s objective is to reduce physical and psychological suffering, and encourage measures of wellbeing and comfort.

Patients requiring palliative care during the course of their illness go through difficult situations that affect their physiological and social dimensions and deteriorate their systems. These patients and their families consequently require care and companionship from the health team. During their stay in the ICU, they perform a series of interventions for patients in an end-of-life situation to define clearly the diagnosis and procedures to follow. In this category, 2 subcategories, described below, are defined. The relevant narrations that characterise it are included in Table 3.

Relevant Category 2 data.

| Management of critical patients and their families in the end-of-life-situation in the ICU | |

|---|---|

| Palliative care and end-of-life feelings | ``I felt many emotions, feelings of sadness, pain, crying, powerlessness for her suffering'' N4P1P2 |

| ``Being in the terminal stage, we could only offer palliative care, focusing on relieving the suffering and reducing the pain.'' N4P1HP1 | |

| [In reference to the end-of-life care that professional staff perform] ``alleviate the patients’ pain and anxiety'' PASJC2P9 | |

| ``In this scenario [ICU], the social and spiritual dimensions of the individuals are not the priority; however, they are essential'' N1P1P1 | |

| ``I think that it is more emotional support that can be given in that moment to the family member'' [In reference to the moment in which the family member receives the communication of the patient’s prognosis] PASJC2P10 | |

| ``We are obsessive about managing suffering and pain; that is, the pain or anxiety that is produced in that patient'' PASJC2P10 | |

| ``When you talk about palliative needs, it means that they are patients that have a symptom burden that must be approached on the spiritual, emotional and physical levels'' PASJ1P4 | |

| ``There is a way to say that; we talk about palliative needs, that is, palliative needs is not only the prognosis but also everything the patient needs and you should always be able to measure that, through nursing and medicine, as well as the pain scale'' PASJ1P4 | |

| ``But there is a lack in evaluating these needs; in the professional staff I think that there is a point of interest at least for it to be optimum in the process.'' PASJ1P16 | |

| ``When the patients enter into palliative care we imitate the pain, the suffering because of bagging, suffering from the tube, suffering due to the cold, suffering from loneliness.'' PASI1P12 | |

| Comprehensive care with quality and support networks | ``We attempt to increase the things that are humanistic; that is, reduce the noise, encourage privacy and ensure that there are no restrictions at all for this family.'' PASI1P15 |

| ``A comfortable position, so that the patient feels more comfortable in bed and for it to be set up in a way that the patient is in a position that really serves for resting'' PASJC2P10 | |

| ``The companionship of family members of the patients in an end-of-life situation is made easier'' PASJI1P13 | |

| ``Since then, our care subjects were widened to include the patient and family'' N1P1P4 | |

| ``The family is defined as an independent focus of intervention, with its own needs.'' N2P1P6 | |

| ``He [in reference to the patient] indicates his worry to us in this regard, for the identification of who would really be the person in his family or the main caregiver with whom he could reach an agreement on those important end-of-life decisions'' PASJC2P1 | |

| ``I cannot make the decision until the pastor arrives to say, until one arrives to that point and religious beliefs come.'' PASJC2P2 | |

| ``I do not see it, because I have a specific schedule that can differ from the family’s schedule.'' Because sometimes the family members have to work all day and we should welcome them at 7:30 at night and that is a beginning to reality'' PASJI1P15 | |

| ``Because if we have those limitations in schedules [for visits], from the unit we can think rather about strengthening the emotional support that nursing provides'' PASIP14 | |

Participative assembly (PA) and narrative (N), paragraph (P), Unit at Hospital San José (SJC), Unit at Hospital San José Infantil (SJI).

During the end-of-life process, a series of feelings of guilt, negation and sometimes acceptance are generated in the face of the various situations, in both the patient and family, and in the health personnel. The multidisciplinary team renders palliative care that attempts to ensure a state of comfort, of satisfaction, for the patient and family by taking care of their basic needs. This palliative care is accompanied by communication that helps to improve the quality of life.

The health personnel identified that, besides the pain, multiple necessities had to be approached, especially emotional and spiritual needs in a comprehensive fashion. The personnel indicated that this transcended the need to identify the evaluation tools required to identify such needs in the patient and family, and to implement them in the daily practice of the ICU health team.

Comprehensive care with quality and support networksDuring the entire process of critical patient care, the multidisciplinary health team renders the patient comprehensive care, based on skills and tools required to solve conflicts and make decisions. This care must be applied in a way that it is integrated into a palliative care plan in an interprofessional fashion, with the objective of meeting the needs of patients and their families. Palliative care attempts to provide comprehensive care to the patient and those in the setting, with the intention of permitting a death free from discomfort and suffering for the patient and his/her family members, in agreement with their wishes, and with the cultural and ethical standards.

The professionals consider the family to be the main source of the beliefs and guidelines for behaviour related to health; the stress the patient suffer through the evolutionary cycle can be manifested by symptoms, that are the expression of the patient’s adaptive processes. The link between the patient and his/her family serves as a support and a platform for developing life in the world surrounding the patient, giving meaning and support to each of the relationships. The professionals indicate that they are respectful and permissive when it comes to fulfilling the wishes of the patients in agreement with their spiritual beliefs.

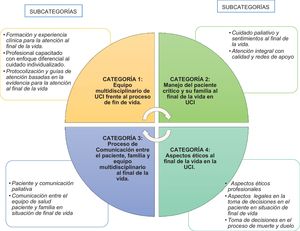

Process of communication among patient, family and multidisciplinary end-of-life teamThis category is defined as all the verbal and nonverbal actions that facilitate and ensure effective communication of relevant information of the patient between the health team and family; the communication promotes empathy, trust, respect and proper decision making. For this category, 2 subcategories are defined (described below). The relevant narratives that characterise this category are included in Table 4.

Relevant Category 3 data.

| Process of Communication among the patient, family members and multidisciplinary end-of-life team. | |

|---|---|

| Patient and palliative communication | ``Information constitutes the main point of encounter between the families and the professional personnel in the intensive care unit'' N2P1P1 |

| ``They [the health staff] require communication skills and great knowledge of the clinical situation and progressively of the personal context of both the patient and the family'' N2P2P3 | |

| ``This situation promotes the physician – patient and family relationship with lesser probabilities of conflicts, some of which can end up in legal actions'' N2P2P7 | |

| ``Search for an appropriate space to develop skills for communication, focused on not causing more pain with the words used with a group of vulnerable people'' N2P2P9 | |

| ``The most important contact with the family arises while giving the daily information'' N2P1P7 | |

| ``A close relationship with the family makes decision making easier by opening spaces of trust.'' N2P2P73 | |

| Communication among the health team, patient and family in an end-of-life situation | ``I always try to talk to my patients and deep within me I feel that they hear me'' N6P2P8 |

| ``We physicians perceive the moment of giving the information as a very tense situation.'' N2P2P1 | |

| ``I [nurse] translated every word to them that the physician said and that they did not understand'' N6P2P9 | |

| ``They [the family members] prayed, they were with him to the last breath'' N6P2P11 | |

| ``I believed that the strength [in reference to the medical meetings with the family] is being able to have the conversation with various members of the family, at the same time as it allows them to clear up any doubts, and the information or the communication is not left to the responsibility of what one person may have understood'' PASJI2P8 | |

| ``There is communication at all times [Among the members of the health team], the management parameters are established in the journal [“Revista médica”], because, well, the majority of us who act on the patient are present'' PASJI2P9 | |

| ``I think that the communication with nursing is different, yes; and this lies in the fact that the family always looks for a hopeful situation'' PASJI2P8 | |

| ``Nobody likes to be lied to, but it is a unanimous petition that the truth be expressed with respect and compassion'' N2P2P5 | |

| ``I think that with respect to this [the processes of end-of-life communication], the main strength is giving the information; sometimes you only give the information to one person and that person conveys the communication to the rest of the family'' PASJI2P9 | |

Participative assembly (PA) and narrative (N), paragraph (P), Unit at Hospital San José (SJC), Unit at Hospital San José Infantil (SJI).

The multidisciplinary team requires effective communication (complete, clear, timely and concise) by means of the transfer of information in the shift changes and in patient transfers, in order to prevent errors, adapt treatments properly and offer the patient quality care. The communication among the health team, family members and patient generates an atmosphere of trust and respect, which facilitates decision making. In addition, strategies to establish appropriate and empathetic communication with the family members must be sought, so that care for patients in an end-of-life situation will be improved. Communication with the patients is affected by their health conditions, given that most of them have oro-tracheal tube (OTT) ventilation, or their state of consciousness or health is not sufficient for effective communication. Consequently, a legal representative has to be identified in the family to whom the necessary information is given.

Communication among the health team, patient and family in an end-of-life situationSuccessful communication transmits, verbally or in writing, what is planned, what is thought, and is necessary when interacting with the patient or family member. This is because the family always looks for hope in the face of the patient’s condition and inadequate communication can generate false expectations. It is important for the health team to have various skills that make it possible for team members to interact with the patient, family and legal representative, in order to report the patient’s health condition and to generate trust at the moment of carrying out procedures and making decisions.

The health personnel indicate that communicating bad news is a difficult, stressful moment, given that they do not have skills to identify the family or legal representative’s susceptibilities. In addition, they state that communication is affected by the sociodemographic situation and cognitive level of the patient and the legal representative (a position that can be rotated from one to another according to personal needs).

Ethical end-of-life factors in the ICUWith respect to ethical reasons, enough have been found to integrate into end-of-life care in the ICU. Three subcategories, which are described below, were defined for this category. The relevant narratives that characterise this category are included in Table 5.

Relevant Category 4 data.

| Aspects of professional ethics | ``The thing is that there is a clinical decision that says that the patient is not going to come out of this, that he/she is in a terminal stage, this is explained to the family and that nothing more is going to be done from the clinical standpoint; from then on arise the concepts of whether we are going to use dysthanasia or euthanasia, then dysthanasia. Because, well, I am going to prolong something certain for the patient and euthanasia simply left that the natural course of the patient, well, what is going to end ends, which has been the end is death'' PASJC2P4 |

| ``The advance directives for me have the highest level in the hierarchy of decision making'' PASIP18 | |

| [In reference to the end-of-life ethical dilemmas with the family members] ``The family feels first of all that there is an action that does not comply with the principle of doing no harm, which is excess activity in the face of a prognosis'' PASI1P22 | |

| [In reference to the professional personnel’s practice] ``extremely based on welfare and very, shall we say, based on doing no harm'' PASI1P22 | |

| ``Going beyond this document [Living Will], that does not happen, it does not occur; so the subject of advance directives as a chain of decision making is complex'' PASI1P19 | |

| ``There are several things that I believe that it is important to clarify: the advance directive of the individual is one thing; it is not of the family!'' PASJ1P13 | |

| ''because we face end-of-life dilemmas every day, making decisions, the research, the science; that is, everything that happens there is a constant bioethics laboratory, we agree on that'' PASJI2P11 | |

| ``Bioethics is not the area of greatest interest of the individuals in intensive care; yes, in spite of what we say to the contrary.'' PASJI2P11 | |

| Legal aspects of decision making in the patient in an end-of-life situation | [When a “Limitation of Therapeutic Efforts” is decided] The entire family group is gathered and it is explained to them in a clearer fashion, and when there are more complications the committee gets together and it is explained to them with the committee of wellbeing and quality, the treating physicians, ICU physicians and everyone because we believe that there might be a legal-medical complication and those situations'' PASJC2P3 |

| ``We do not know the law''; the law has many facets and we take it for granted that we know the law and suddenly we have had more information about the ethics part'' PASJ1P12 | |

| ``There is a lot of influence, not only from the family but also from the spiritual leader, in making the decisions'' PASJC2P2 | |

| ``Ethical conflicts? Yes, there is a procedure for solving conflicts related to treatments considered potentially inappropriate.'' PASJC2P11 | |

| [In reference to conflicts with family members about decision making] ``It is going beyond a written directive coming from the patient.'' PASJC2P6 | |

| ``Look at it from the legal point of view, the thing is that the children in that situation can claim that the mother’s directive was not a real directive but was circumstantial'' PASJ1P14 | |

| ``If it is a family nucleus of 6 people and one who is the person who is not decided, but due to that person it happens that intensive treatments are continued, and you as a professional are the one that is left exposed in the face of the law for the family conflict'' PASJC2P4 | |

| ``The work should be done with the family so that they understand the reason why the decision for a Limitation [Limitation of Therapeutic Efforts] is reached, for a different focus'' PASJC2P3 | |

| ``We have no clear or routine procedures or tools for prognostic evaluation; the protocol would help to make decisions with these patients. A first good practice for our units could be the preparation of a multidisciplinary protocol for end-of-life care adapted to the recommendations of the scientific associations'' PASI1P3'' |

Participative assembly (PA) and narrative (N), paragraph (P), Unit at Hospital San José (SJC), Unit at Hospital San José Infantil (SJI).

The health team attempts to provide comprehensive palliate care for the patients and those in their surroundings. The team’s intention is to reduce the discomfort and suffering for the patient and family members in agreement with their wishes and with clinical standards and ethical and cultural factors, without omitting the principles of wellbeing and doing no harm in the resolution of ethical dilemmas.

The professionals state that advance directives have the highest level in the decision making hierarchy, above substitute decision making, or a principle of absolute welfare by the professional. However, they report that when there is a conflict between the wishes of the patient and those of the family, a legal process begins that requires the intervention of the medical board and the ethics committee. The health personnel also indicate that extensive knowledge is needed to handle the different ethical dilemmas that are presented in the ICU.

Legal aspects in decision making with the patient in an end-of-life situationThe ICUs should have protocols and tools available to facilitate evaluating the prognosis and making decisions when there are patients in end-of-life situations. In addition, all the professionals must have knowledge and be skilled in legal and bioethical aspects, to have a framework within which to act. The subject is complex because each situation needs to be handled differently.

Limiting life support, which frequently happens with the critical patient, should be undertaken following the guidelines and recommendations established by the scientific associations and institutions in charge of the issues involved. Such limitation should be aimed at favouring the right to autonomy, to cover the needs and beliefs of the patients and family members.

Decision making in the process of death and mourningAs for decision making and respect for the patient’s wishes, it is common for there to be ethical dilemmas that have to be handled on a daily basis. The narratives of the health personnel reflect that there can be a conflict between the wishes of the patient and those of the family; this means that the health personnel have to face situations that put them at risk ethically and legally, given that the prognosis and treatment do not always agree with the wishes of the family or their spiritual leader.

The process of mourning requires companionship and humanisation of ICU care. Training in end-of-life care for the professionals, shared decision making and psychological support are relevant for the health personnel, who needs tools to face, support, give companionship and channel the feelings of the patient and the family.

DiscussionData analysis revealed four thematic categories: multidisciplinary ICU team in the face of the end-of-life-process, end-of-life management of the critical patient and the family in the ICU, Process of Communication among the patient, family and multidisciplinary end-of-life team, and end-of-life ethics aspects in the ICU. These categories describe how the health team feels and orient strategies for improving end-of-life care.

While giving care to the patient in the end-of-life process in the ICU, health personnel are likely to live through emotional experiences when faced with the death of the patient. This leads to having feelings such as guilt and frustration, experiences that have been described in previous studies, demonstrating that the professionals feel guilt or doubts after a patient’s death.21 These findings coincide with a study carried out in Indonesia, which describes how the nurses present affliction deriving from the loss of patients that affects their emotional, cognitive, spiritual, relational and professional wellbeing.22

Likewise, in end-of-life care for patients, relationships are established among the health team, patient and family, which must take into consideration the human and social context that surrounds something as essential as life, not only of the patient but also of the family members that require support and attention. The theorist Watson emphasises the importance of the help-trust relationship, which is fundamental for the family, especially during the process of anticipated mourning and mourning.23 This finding coincides with the study by Zamora et al.,24 which demonstrated that the caregivers (family members) present high levels of anxiety and they feel overburdened; the reason for which a good relationship and good communication with the family and the patient is important to alleviate the effects that this causes them.

In clinical practice the family usually hopes that the course of the illness leads to recovery and not to complications or death. At the same time, the coping strategies developed by the members of the health team can lead to viewing death as a natural, often necessary process, which can make the ICU seem like a unit lacking humanisation to people not connected to it. Likewise, the physical, emotional and spiritual experiences of the patient and the family at the end of life require emotional support, symptom management and effective communication that provides a comprehensive approach and promotes humanisation in the ICUs. The study of Samar et al.25 proposes that it is necessary to use guidelines for initial evaluation that make it possible to make decisions, establish better communication with the patient and the family and identify end-of-life needs, to reduce their stress and anxiety.

As for decision making and respect for the advance directives, the health personnel have to face every day a legal and ethical void, and experience situations that put them at risk. For that reason, they require training and support from other disciplines that can give them reinforcement or tools to face these challenges, given that this process requires companionship and humanisation in the ICUs. There are similarities in this respect with the study by Crowe26 on end-of-life care in the ICU, which reflects the importance of the palliative role and the existence of barriers to deciding to withdraw therapies that maintain life and to provide good end-of-life care. In Colombia, there is a legal right to cease unnecessary medical treatments that do not represent a life with dignity for the patient.10

Another important aspect is the humanisation of care in the ICU. A contribution to the process is the generation of documentation providing evidence and guidelines that make it possible to consider the wishes of the family and the patient when decisions must be made; training is relevant for being able to face the frequent ethical dilemmas in the ICUs. The study of Guijaro and Amezcua27 in Spain also emphasises the importance of humanisation in ICUs, relating it to good practice; they stress the patient needs for communication, family support, care, confidentiality and preservation of intimacy, all of which bring about greater wellbeing. This view is similar to what is proposed in the study by Brito and Librada,28 who consider training and implementation of compassionate ICU approaches to be fundamental for health personnel.

Likewise, the importance for the ICU professionals of working in teams with other professionals who interact and back end-of-life care has been identified, to ensure a state of comfort and help for the basic needs that contribute to improving the quality of life and effective end-of-life communication. These aspects are described in the Rautureau29 study, in which the support for end-of-life care given by a multidisciplinary team is identified by a nurse, using a clinical situation to provide the details. Although ICU professionals are trained for this service, the feeling of guilt related to the care given is still common. The study of Betriana and Kongsuwan22 also described the experiences of a group of Muslim nurses in an ICU; they lived through a stage of grief due to the loss of patients, affecting their emotional, cognitive, spiritual, relational and professional wellbeing.

In the end-of-life process, the feelings and difficult circumstances the family and the patient undergo affect them physically and psychologically. The feelings and situations also generate challenges and goals for the health team that attempts to render care and support in the physical, psychological and emotional part. This is shown in nursing theory of the calm end of life of Ruland and Moore,30 who see a relationship between aspects of good death and the encouragement of a calm setting for the patient, surrounded by family members, treating pain and providing wellbeing and peace.

A medical round is a good time for the various members of the health team to carry out an analysis, to evaluate the therapy and prognosis for the patient, and to provide information to the patient and family. It is a tool for individualising the treatment and interventions corresponding to the needs and human answers characteristic of the patient at the end of life. This result is similar to the study by Mora,31 who stresses how important it is to review clinical practice in a critical and organised fashion, without neglecting ethics and making it possible to give a proper response to the dignity of the patient and family.

The multidisciplinary team requires effective communication (complete, clear, timely and concise), through the transfer of care and of information at the shift changes. Such communication prevents errors, ensures proper treatment and provides quality care for the patient that generates trust and respect, and facilitates decision making. This importance is reflected in the study of Achury and Pinilla,32 demonstrating that the nurse has to recognise the process of therapeutic communication as a cornerstone in patient care. This communication has to be based on knowledge, a helpful relationship and active listening to improve the skills of the professional and the quality of the communication.

The ICU health team attempts to provide palliative care for end-of-life patients so as to allow a death with the least discomfort and suffering for the patient and family, in agreement with their wishes and with clinical, cultural and ethical standards. The team tries to solve ethical dilemmas based on the principles of welfare and doing no harm, and without involving their own feelings. This is related to Resolution 1216 (2015) in Columbian law, which establishes palliative care as a right in order to improve the quality of care to patients at the end of their lives; the law states that these patients should have their pain reduced, their suffering relieved and all the emotional, social and spiritual aspects given support.10

The complicated decisions that are made concerning critical end-of-life patients can lead to conflicts among professionals, family members and patients. Consequently, the ICU professional should have the skills and tools needed available for resolving conflicts. This is shown by a study in Mexico, which concludes that end-of-life education and training should be promoted for physicians and nurses, given that it is necessary to improve communication with patients in an end-of-life situation to provide them with better care.7

It is made evident that, for the ICU health personnel, it is important that instituting treatment withholding (frequent in the critical patient) be carried out following the guidelines and recommendations established by the scientific associations and institutions in charge of the matter, and that its aim should be to cover the needs and beliefs of the patients and family members. This importance is demonstrated in the study by Nabal et al..,33 who conclude that the quality of the clinical register with respect to selection, decision making and treatment at the end of life should be improved, and propose the use of a template to do so.

Among the results, it is emphasised that research on this issue is needed. In Colombia, there is no evidence of studies related to the approach to the ethical dilemmas and the legal implications that withholding treatment has. This puts the health personnel, especially the professionals that have to make the decisions, at risk. A study carried out by Sepúlveda34 revealed that there are obstacles during the death process to ensuring patient rights and the fulfilment of professional duties; the study also demonstrated the need to apply the law for a dignified death and advance directives in non-oncological areas and to provide greater training at the ethical, spiritual and sociocultural levels for care in end-of-life situations.

Limitations of the studyAs this is a qualitative study, it is important to be careful about the transferability of the results. Consequently, the characteristics of the units and the study participants have to be taken into consideration. It is also important to remember that population recruitment was coordinated with those in charge of the institutions, which could have affected the conversations and the participation of the study subjects. In addition, there were power asymmetries among the participants in how the groups were set up, which were associated to variables such as educational level, profession, sex, age and professional experience. However, a researcher from outside the ICU moderated the assemblies, which encouraged a more horizontal atmosphere of participation, and the expression of experiences from the perspective of each role. Likewise, the anonymous written narratives as an analysis source promoted triangulation of the data, minimising the bias from power asymmetry that could have occurred in the assemblies.

ConclusionsThe professionals view conserving the quality of life during the patient’s stay in the ICU to be a therapeutic objective. It is important to remember that the care for the critical patient must be individualised. For the health personnel, it is essential for there to be evidence-based guidelines that facilitate multidisciplinary management, personalisation of care and promote the right to autonomy to cover the needs and beliefs of the patients and family members.

The professionals stated that, besides patient pain, the emotional and spiritual needs of the patient have to be handled, which means that tools that permit evaluating them in clinical practice have to be used. In addition, the health personnel emphasise that communication among the health team, family members and patients builds an atmosphere of trust and respect, which facilitates end-of-life decision making.

The legal and ethical aspects involved in offering care to the patient at the end of his/her life entail many ethical dilemmas that the health professional has to face. For this reason, specific tools and skill training have to be created, bearing in mind the personalisation of the care.

It is essential to increase research that provides greater knowledge on end-of-life care; decision making centred on the patient and the family; emotional and spiritual support for the family; and humanisation of the ICUs for the wellbeing of patients and family members.

Study implicationsThe health personnel view preserving quality of life during a patient’s stay in the ICU as a therapeutic objective. It is important to remember that care for the critical patient has to be individualised. Preparing evidence-based guidelines is essential to facilitate multidisciplinary management, to personalise the care and to favour the right to autonomy so that the needs and beliefs of the patients and relatives are covered.

The professionals stated that, besides the pain, emotional and spiritual needs have to be approached. This means that tools that permit evaluating these needs in daily practice are required. In addition, it should be emphasised that communication among the health team, family members and patients brings about an atmosphere of trust and respect, which facilitates end-of-life decision making.

FundingStudy funded by the Fundación Universitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (University Foundation of Health Sciences), through the internal call for promotion of research, Act 11 (2018).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Zambrano SM, Carrillo-Algarra AJ, Augusto-Torres C, Katherine-Marroquín I, Enciso-Olivera CO, Gómez-Duque M. Perspectiva de los profesionales de la salud sobre cuidados al final de la vida en unidades de cuidados intensivos. Enferm Intensiva. 2020;31:170–183.