to explore the experience of family members of a relative hospitalised in the Intensive Care Unit and recognise their emotions and needs and describe the phases or milestones they go through and the strategies they use to cope with the situations that arise.

MethodQualitative study developed under the grounded theory method proposed by Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin. During the period from July 2017 to July 2019, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 26 relatives of hospitalised patients in fifteen third-level private clinics in the city of Manizales and Medellín, Colombia. In the latter, 200 h of participant observation were performed in ICUs of two private third-level clinics. The analysis procedure consisted of a microanalysis of the data and the process of open, axial, and selective coding of the information was continued.

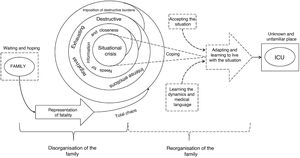

ResultsWe identified that the experience of relatives when they accompany their sick relative in the Intensive Care Unit is represented in two categories: family disorganisation which is characterised by generating a change and mismatch in family dynamics and, family reorganisation in which a restoration of order is sought to cope with the situation.

ConclusionsThe family in the Intensive Care Unit develops a situational crisis characterised by intense, varied, and negative emotions and needs that wear down the relatives. Faced with this, family members undertake a reorganisation process to restore the order of family dynamics to cope with the situation and overcome difficulties.

Explorar cómo vive la familia la experiencia de tener un pariente hospitalizado en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos y reconocer sus emociones y necesidades, describir las fases o momentos por los que pasan y las estrategias que utilizan para hacerle frente a las situaciones que se les presentan.

MétodoEstudio cualitativo desarrollado bajo el método de la teoría fundamentada propuesta por Anselm Strauss y Juliet Corbin. Durante el periodo de julio de 2017 a julio del 2019 se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas a 26 familiares de pacientes hospitalizados en quince clínicas privadas de tercer nivel de la ciudad de Manizales y Medellín, Colombia. En esta última se realizó 200 horas de observación participante en UCIs de dos clínicas privadas de tercer nivel. El procedimiento de análisis consistió en un microanálisis de los datos y se continuó con el proceso de codificación abierta, axial y selectiva de la información.

ResultadosSe identificó que la experiencia de los familiares cuando acompañan a su pariente enfermo en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos se representa en dos categorías: 1) Desorganización familiar (como una crisis situacional): implica un cambio y desajuste de la dinámica familiar; y 2) Reorganización familiar en la que se busca un restablecimiento del orden para hacerle frente a la situación.

ConclusionesLa familia en la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos desarrolla una crisis situacional caracterizada por emociones y necesidades intensas, variadas y negativas que desgastan a los familiares. Frente a esto, los familiares emprenden un proceso de reorganización para restablecer el orden de la dinámica familiar para hacerle frente a la situación y superar las dificultades.

Family members in ICU are recognised as important and active in the care of the critically ill. However, their relative's situation causes them suffering and they have multiple needs and emotions, which predisposes them to developing post-traumatic stress.

What does this paper contribute?The study contributes towards the understanding of the experience of relatives when they are in the ICU. We introduce different strategies that correspond to different conceptual levels. The open-door ICU is a policy framed within the philosophy of family-centred care and implemented in interventions such as facilitating visits, and the collaborative participation of families in decision-making and in the care itself. The interventions that need to be shaped and individualised through specific activities are, for example, the family-centred interdisciplinary round, or training workshops for specific care.

Implications of the studyThe study contributes towards gaining a knowledge and understanding of the situation of family members in the ICU to plan comprehensive and humanised care interventions and to strengthen strategies such as "Humanisation of Intensive Care (HICU)" and "Patient-centred and family-centred care PFCC”

Patient and Family-Centred Care (PFCC) is a way of steering healthcare towards autonomy and respect for the patient and family through the design of care plans that integrate into established therapies the personal values, life patterns and beliefs of the patient and family.1 PFCC highlights the importance of the family in care processes and is therefore considered a way of humanising health services.2

In line with the above, Bautista-Rodríguez et al.3 state that recognising the family as a central axis of care actions fosters the humanisation of hospital spaces like the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Thus, including family members in patient care helps us evolve from a bio-medical and disease-centred care model towards a holistic care model in which the family is conceived as inseparable from the patient.4 And therefore including the family in care processes helps us recognise them as not only an integral part of the patient, but also as the object of nursing care.5

The family is part of the patient's context and has important functions such as providing physical and emotional resources to maintain the health of each of its members, and forming a support system in times of crisis, such as when a member becomes ill.6 De Beer and Brysiewicz7 argue that the family plays a vital role in the patient's life as it becomes the patient's voice in situations where they lose the ability to make decisions for themselves as a result of a particular illness or clinical situation.

The admission of a sick person to the ICU can disrupt family dynamics because the roles of its members are altered, according to Campo-Martínez and Cotrina-Gamboa8 they suffer due to the serious condition of their relative, the setting is unfamiliar and frightening,9 and everything happens quickly and unexpectedly.10,11 This predisposes family members to states and emotions such as anxiety, stress, uncertainty and depression,12–14 which affect their functions and roles within the family and society.8

Likewise, a stay in the ICU can leave strong impressions on relatives,15 to the point of suffering post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which can affect their ability to integrate and fulfil their functions in society.9,16 PTSD is recognised as a stress disorder resulting from a person's exposure to a traumatic experience or from multiple experiences of patients and their relatives related to acute and chronic illnesses. In this regard, sudden and unexpected onset of illness, invasive medical therapies, and accumulated adversity are potential factors for the development of PTSD.16,17

It is recognised that relatives of ICU patients experience the burden and stress of caring for their relative, and struggle to cope with the situation they are experiencing.10 However, relatives feel that ICU staff do not recognise their needs and concerns18 and, in some cases, relatives do not feel that professionals are compassionate towards them or have any idea of what they feel when they are in the ICU.19 In view of this, Montoya-Tamayo et al.20 argue that nurses should play a more active role in the care of the family of ICU patients.

Hetland et al.14 state that knowing the experiences of family members in the ICU helps nurses understand them and to put themselves in their place. This helps to create and implement inclusive frameworks and view the family as a central axis of care. Such recognition fosters comprehensive care, the reduction of adverse psychological effects and the creation of humanised healthcare environments.3,21

In relation to the above, understanding the experience of families in the ICU can help to enhance proposals such as "Nursing Now"21 and the "Humanising Intensive Care" (IC-HU) project.22 In the former, by consolidating and positioning nurses as a leaders in health services based on holistic care models centred on people and their families, and in the latter, by contributing to the development of strategies that encourage humanising care in the ICU.

Based on the above, the general objective of this study was to explore how families experience having a relative hospitalised in the ICU. The specific objectives were also to recognise their emotions and needs, and describe the stages and situations they go through, and the strategies they use to cope.

MethodStudy typeThe study was framed within the qualitative research approach,24 and was developed based on Strauss and Corbin’s grounded theory. The latter was considered the most appropriate method for constructing an abstract analytical scheme to describe the situations experienced by families while in the ICU. Furthermore, this method enabled a theoretical construction of the study phenomenon through concepts based on the data and through systematic, rigorous work.25

Respondents and data collectionThe study included relatives of hospitalised patients from 15 private third level hospitals, 3 in the city of Manizales and 12 in the city of Medellín, Colombia. In addition, in the city of Medellín, participant observation was conducted in the ICU of 2 private third level hospitals. Of the total ICUs, 8 were surgical and 9 were medical.

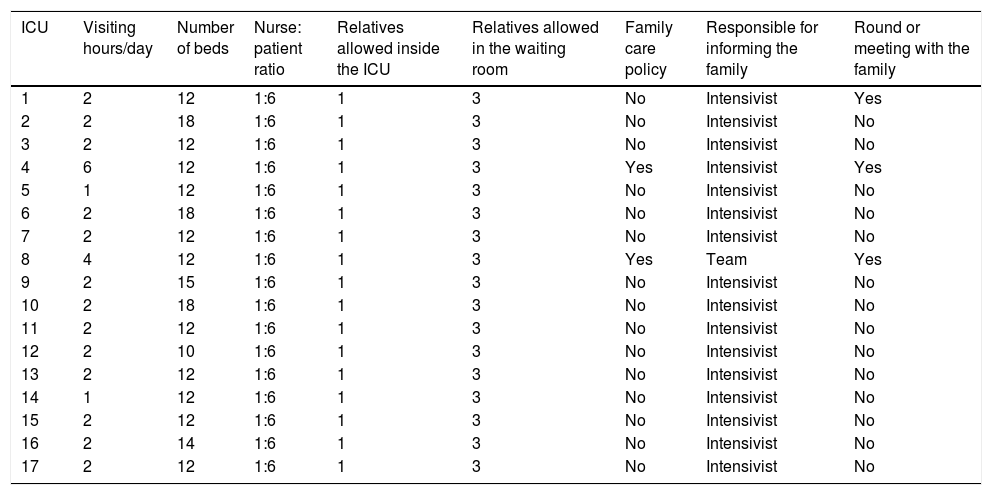

As described in Table 1, the units had an average of 13 critical care beds, and the nurse: patient ratio was 1:6. All the institutions allowed 3 family members to stay in the waiting room during visiting hours. However, only one was allowed inside the unit. An average of 2 h was available for visiting, spread over 2 days. Two institutions had a formal policy for family care, characterised by extended visiting hours and special conditions for family care, such as: a team comprising a nurse, an intensivist and a psychologist to provide information, education, and follow-up to families; specific and scheduled rounds by intensivists to attend to families; and educational talks aimed at patients' relatives. In the other institutions, family care was provided only when requested.

Characteristics of Intensive Care Units.

| ICU | Visiting hours/day | Number of beds | Nurse: patient ratio | Relatives allowed inside the ICU | Relatives allowed in the waiting room | Family care policy | Responsible for informing the family | Round or meeting with the family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | Yes |

| 2 | 2 | 18 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 3 | 2 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 4 | 6 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | Yes | Intensivist | Yes |

| 5 | 1 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 6 | 2 | 18 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 7 | 2 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 8 | 4 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | Yes | Team | Yes |

| 9 | 2 | 15 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 10 | 2 | 18 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 11 | 2 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 12 | 2 | 10 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 13 | 2 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 14 | 1 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 15 | 2 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 16 | 2 | 14 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

| 17 | 2 | 12 | 1:6 | 1 | 3 | No | Intensivist | No |

ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

The data collection period was between July 2017 and July 2019. The search for participants was done through convenience, snowball and criterion, or opportunistic sampling.26 As the categories emerged and the analysis process progressed, the selection of participants was guided by theoretical sampling to achieve saturation of the categories.

Two techniques were used for the data collection, the semi-structured interview and participant observation.

For the interviews, the inclusion criteria for the participants were relatives who fulfilled the role of representing the family to the unit staff, accompanied the patient during their entire stay in the ICU, their experience had been in the 6 months prior to the interview, and their relative had been hospitalised in the ICU for a minimum of 48 h.

We avoided interviewing relatives of patients managed under limited therapeutic effort, in the process of resuscitation, or who had been admitted in the last 24 h. The family members in these circumstances were considered to be at greater risk of developing an anxiety crisis.

A total of 26 interviews were conducted and all those invited agreed to participate in the study. The number of respondents was determined from the theoretical data saturation of the categories. Two of the respondents were members of the same family, however, these interviews were conducted at various times. The interviews were conducted by the lead investigators and lasted approximately 30–90 min. During the interview, the participant's gestures, attitudes, and non-verbal language were observed, recorded in a field diary, transcribed, and analysed together with the interview. Pseudonyms were assigned to people, places or institutions mentioned by the respondents.

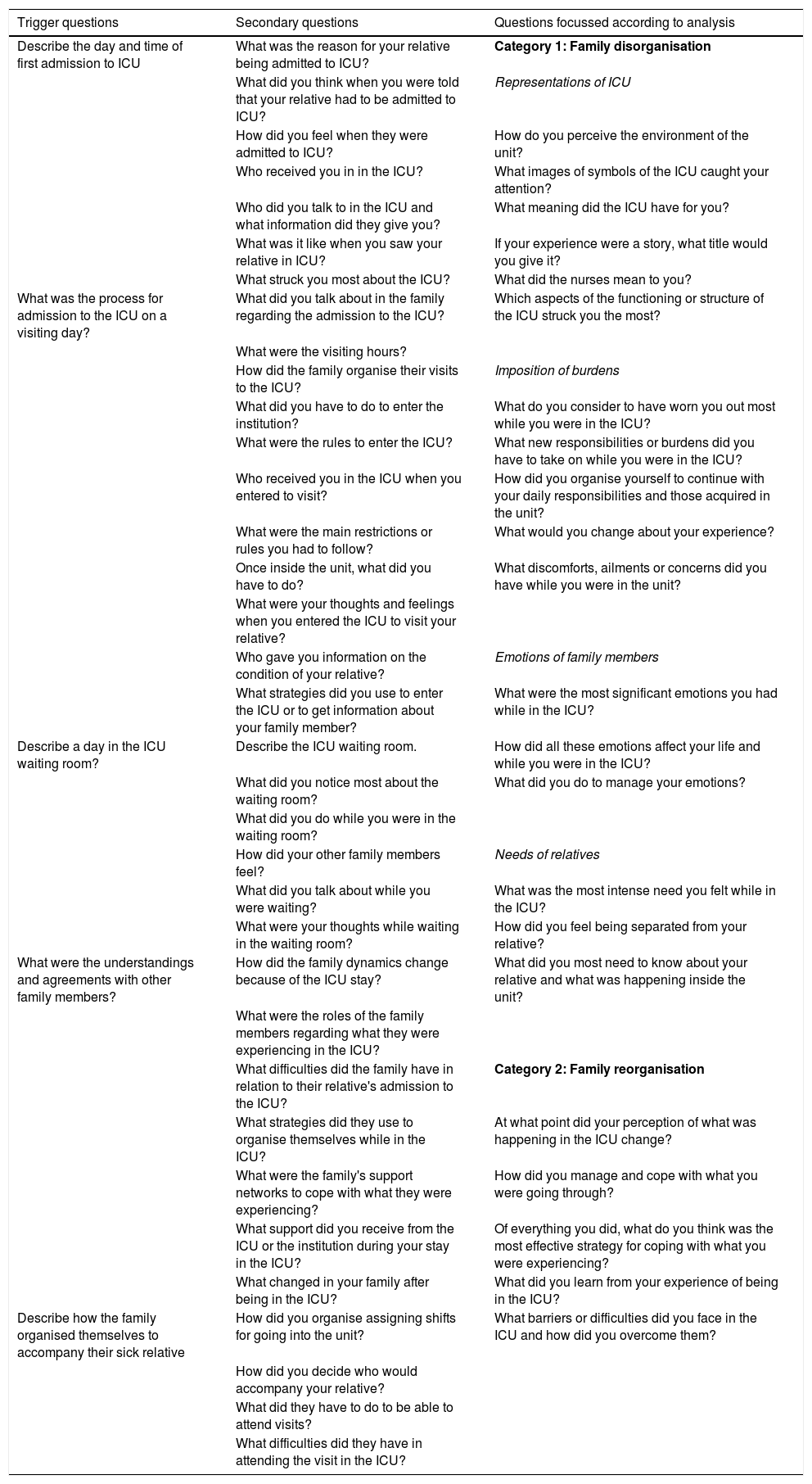

The interviews were conducted using a guide of 5 items or open and descriptive questions27 to trigger conversation. As described in Table 2, secondary questions were asked during the interview to deepen the discussion. Likewise, as the analysis progressed and the theory emerged and was refined, the questions became more focused.28

Interview guide.

| Trigger questions | Secondary questions | Questions focussed according to analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Describe the day and time of first admission to ICU | What was the reason for your relative being admitted to ICU? | Category 1: Family disorganisation |

| What did you think when you were told that your relative had to be admitted to ICU? | Representations of ICU | |

| How did you feel when they were admitted to ICU? | How do you perceive the environment of the unit? | |

| Who received you in in the ICU? | What images of symbols of the ICU caught your attention? | |

| Who did you talk to in the ICU and what information did they give you? | What meaning did the ICU have for you? | |

| What was it like when you saw your relative in ICU? | If your experience were a story, what title would you give it? | |

| What struck you most about the ICU? | What did the nurses mean to you? | |

| What was the process for admission to the ICU on a visiting day? | What did you talk about in the family regarding the admission to the ICU? | Which aspects of the functioning or structure of the ICU struck you the most? |

| What were the visiting hours? | ||

| How did the family organise their visits to the ICU? | Imposition of burdens | |

| What did you have to do to enter the institution? | What do you consider to have worn you out most while you were in the ICU? | |

| What were the rules to enter the ICU? | What new responsibilities or burdens did you have to take on while you were in the ICU? | |

| Who received you in the ICU when you entered to visit? | How did you organise yourself to continue with your daily responsibilities and those acquired in the unit? | |

| What were the main restrictions or rules you had to follow? | What would you change about your experience? | |

| Once inside the unit, what did you have to do? | What discomforts, ailments or concerns did you have while you were in the unit? | |

| What were your thoughts and feelings when you entered the ICU to visit your relative? | ||

| Who gave you information on the condition of your relative? | Emotions of family members | |

| What strategies did you use to enter the ICU or to get information about your family member? | What were the most significant emotions you had while in the ICU? | |

| Describe a day in the ICU waiting room? | Describe the ICU waiting room. | How did all these emotions affect your life and while you were in the ICU? |

| What did you notice most about the waiting room? | What did you do to manage your emotions? | |

| What did you do while you were in the waiting room? | ||

| How did your other family members feel? | Needs of relatives | |

| What did you talk about while you were waiting? | What was the most intense need you felt while in the ICU? | |

| What were your thoughts while waiting in the waiting room? | How did you feel being separated from your relative? | |

| What were the understandings and agreements with other family members? | How did the family dynamics change because of the ICU stay? | What did you most need to know about your relative and what was happening inside the unit? |

| What were the roles of the family members regarding what they were experiencing in the ICU? | ||

| What difficulties did the family have in relation to their relative's admission to the ICU? | Category 2: Family reorganisation | |

| What strategies did they use to organise themselves while in the ICU? | At what point did your perception of what was happening in the ICU change? | |

| What were the family's support networks to cope with what they were experiencing? | How did you manage and cope with what you were going through? | |

| What support did you receive from the ICU or the institution during your stay in the ICU? | Of everything you did, what do you think was the most effective strategy for coping with what you were experiencing? | |

| What changed in your family after being in the ICU? | What did you learn from your experience of being in the ICU? | |

| Describe how the family organised themselves to accompany their sick relative | How did you organise assigning shifts for going into the unit? | What barriers or difficulties did you face in the ICU and how did you overcome them? |

| How did you decide who would accompany your relative? | ||

| What did they have to do to be able to attend visits? | ||

| What difficulties did they have in attending the visit in the ICU? |

ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

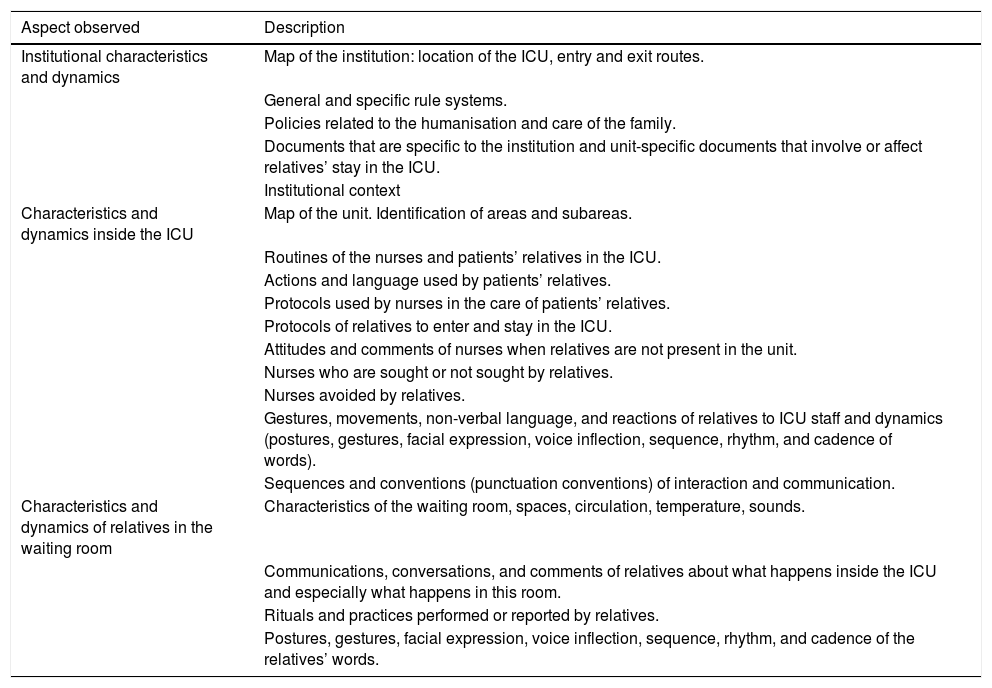

The interviews were also complemented with 200 h of participant observation, conducted by the principal investigator to triangulate the information collected in the interviews and observe the relatives first-hand during their stay in the ICU. The characteristics of the institutional and ICU setting were observed, as well as the behaviours, attitudes, and dynamics of the relatives during their stay in the unit.

A formal presentation was made to the unit staff to access the institutions and on admission of each patient the investigators introduced themselves to the relatives informing them of their purpose and role in the unit. After access to the field, 15-day observation periods were scheduled followed by 15-day analysis periods. The observation was based on an observation guide described in Table 3.

Observation guide.

| Aspect observed | Description |

|---|---|

| Institutional characteristics and dynamics | Map of the institution: location of the ICU, entry and exit routes. |

| General and specific rule systems. | |

| Policies related to the humanisation and care of the family. | |

| Documents that are specific to the institution and unit-specific documents that involve or affect relatives’ stay in the ICU. | |

| Institutional context | |

| Characteristics and dynamics inside the ICU | Map of the unit. Identification of areas and subareas. |

| Routines of the nurses and patients’ relatives in the ICU. | |

| Actions and language used by patients’ relatives. | |

| Protocols used by nurses in the care of patients’ relatives. | |

| Protocols of relatives to enter and stay in the ICU. | |

| Attitudes and comments of nurses when relatives are not present in the unit. | |

| Nurses who are sought or not sought by relatives. | |

| Nurses avoided by relatives. | |

| Gestures, movements, non-verbal language, and reactions of relatives to ICU staff and dynamics (postures, gestures, facial expression, voice inflection, sequence, rhythm, and cadence of words). | |

| Sequences and conventions (punctuation conventions) of interaction and communication. | |

| Characteristics and dynamics of relatives in the waiting room | Characteristics of the waiting room, spaces, circulation, temperature, sounds. |

| Communications, conversations, and comments of relatives about what happens inside the ICU and especially what happens in this room. | |

| Rituals and practices performed or reported by relatives. | |

| Postures, gestures, facial expression, voice inflection, sequence, rhythm, and cadence of the relatives’ words. |

ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

The greatest difficulty in the observation was accessing the field because the staff perceived the investigator as an assessor; however, prolonged stays, constant dialogue with the staff and the academic reports on the field work helped establish a rapport. The investigator acted to convey information between relatives and the unit, which helped form trusting relationships and identify key informants within the data collection process. The information collected was recorded in a field diary, then transcribed and included in the analysis process.

AnalysisThe analysis process was based on Strauss and Corbin’s29 grounded theory. This analysis was conducted in parallel to the collection of information, guided by theoretical sampling and concluded when theoretical saturation of the categories was achieved.

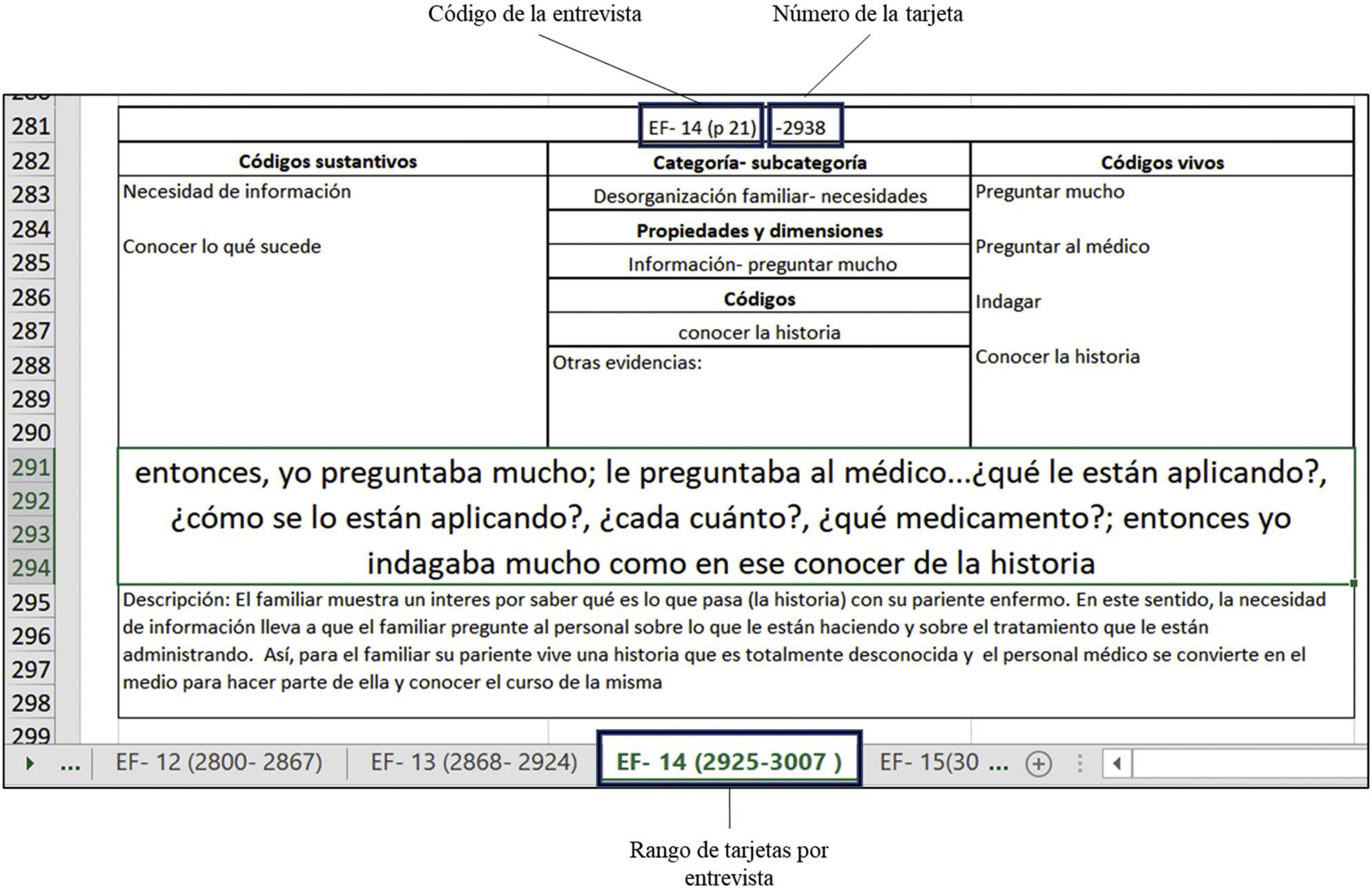

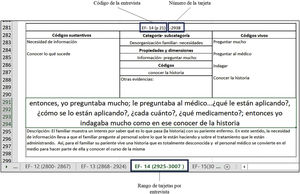

The analysis began with a micro-analysis of fragments of interviews or observation on analysis cards designed in Excel®, as shown in Fig. 1. A total of 4379 cards were constructed corresponding to the number of codes obtained from the analysis process.

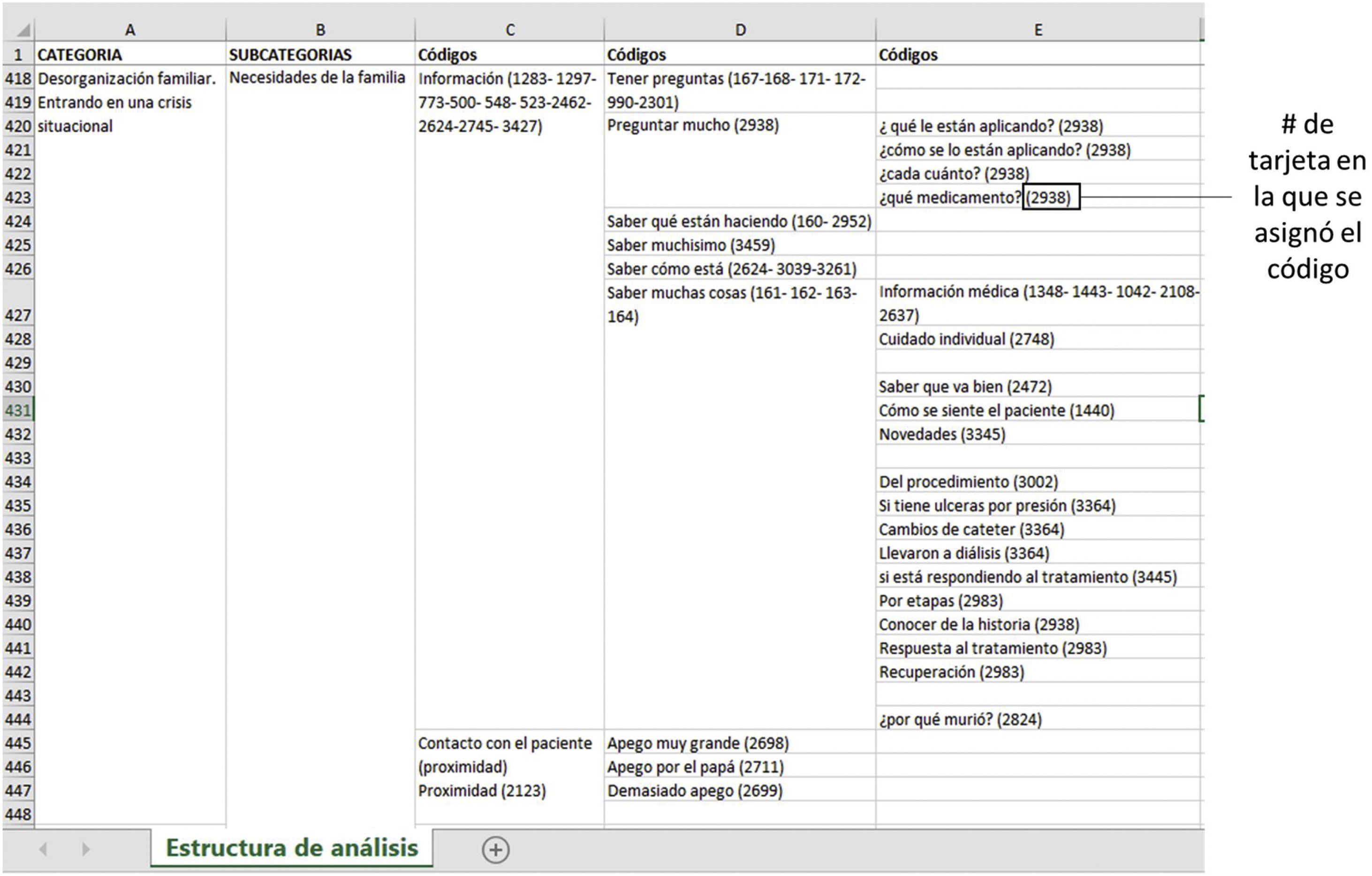

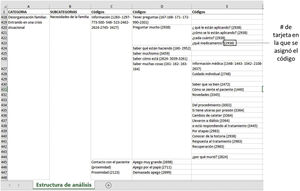

The cards were then grouped according to their similarities, from which categories, subcategories, properties, and dimensions were identified, following open coding and axial coding procedures,30 and the relationships between categories and their components were established. To achieve the above, the codes obtained from the analysis cards were systematised in Excel®, as shown in Fig. 2, from which code books were created with the categorical structure. Each code was accompanied by its respective card number so it could be found in cases where it was necessary to revisit the code, category, or subcategory.

Finally, through selective coding and theoretical linkage, a central category was achieved: "the process of family situational crisis". Analytical tools such as analytical and theoretical diagrams and memos were also used.

On completion of the fieldwork, the results were returned to the institutions where the fieldwork was conducted and to the people interviewed. In the hospitals, the nurses were surprised to learn about the situation experienced by relatives outside the unit. The relatives stated that they identified with the analysis of the information and with the categories presented, especially regarding the emotions and needs they experience.

Ethical aspectsThe project was submitted to the Health Research Ethics Committees of the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana and the Universidad de Antioquia de Medellín, Colombia. Both gave their endorsement through the actas of 08 June 2017 and CEI-FE 2017-14, respectively.

All participants were asked for their informed consent. The consent form described the purpose, risk-benefit and aspects related to respect, autonomy, and confidentiality of the study. This information was explained verbally at the beginning of each interview.

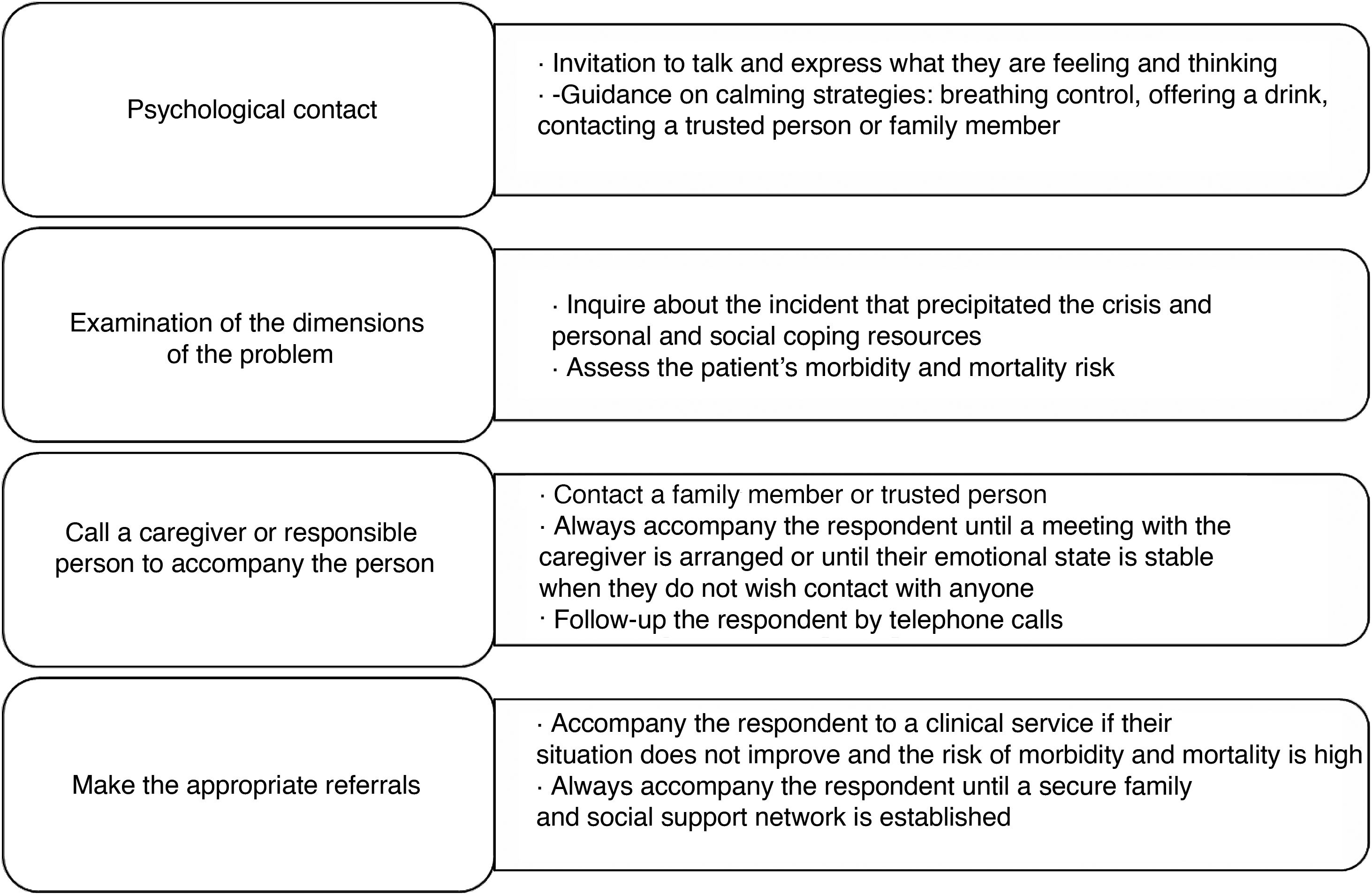

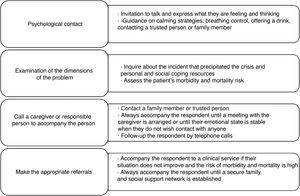

Prior to starting data collection, as part of the exploratory study, a social worker with expertise in the psychological, emotional and care of families in the ICU, and a nurse coordinator of the ICU and researcher in family issues were interviewed. These professionals highlighted the psychological and emotional vulnerability of patients' families when they are in the unit. Therefore, a psychological first aid protocol was created to prevent emotional damage and upset in the relatives. As described in Fig. 3, this protocol was based on 4 interventions: the psychological context, examining the dimensions of the problem, calling on a guardian or responsible person to accompany the person and making the appropriate referrals.

It was not necessary to use this protocol, no major difficulties were encountered, although there was some crying. In fact, some of the relatives found the interviews a liberating experience.

Criteria of rigourThe following were considered as criteria for the rigour of qualitative research: credibility, auditability, and transferability.

In terms of credibility, a process of constant reflexivity was followed. The lead investigator oversaw the processes of collecting, transcribing, and analysing the information gathered. The interviews were recorded, and observation was recorded and transcribed into field diaries immediately at the end of the observation day. Triangulation techniques were used to contrast the data obtained through the interviews with the data collected through observation so that, during the analysis, codes were assigned that represented the experiences of the family members as closely as possible. Similarly, the investigators were triangulated by conducting parallel analysis exercises that were then validated between the two.

In addition to all the above, a search was made for negative cases, which, based on the characteristics of the emerging categories, were considered to be those relatives who felt their experience of being in the ICU was positive and did not significantly affect the family dynamics. There was only one respondent with this characteristic.

In terms of auditability, the research was presented to academic communities of the doctoral training programme from which the study is derived and to disciplinary and professional peer reviewers.

Regarding transferability, the context and respondents were described in detail, identifying the applicability of results in situations where family members have similar experiences to those in the ICU.

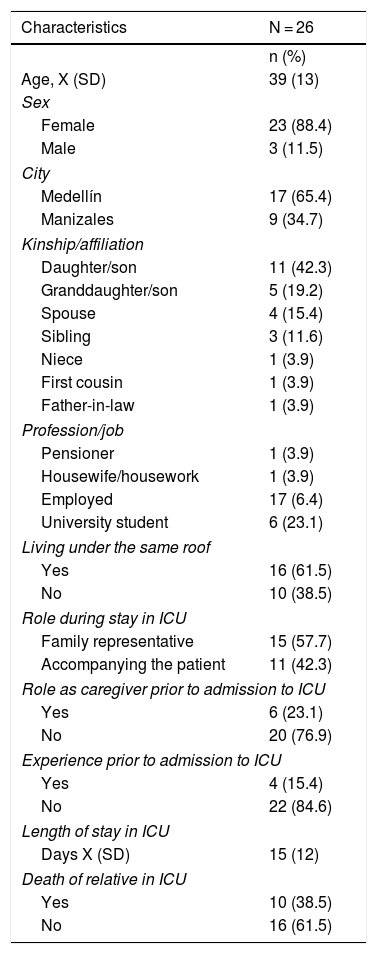

ResultsThe sample consisted of 26 participants. The mean age was 39 years, and most were women (88.4%). The most common relationship to the patient was son or daughter. Of the respondents, 61.5% lived under the same roof with the patient, 23.1% were caregivers prior to the patient's admission to the ICU, 57.7% were representatives of the family to the ICU staff during the ICU stay, 15.4% had had at least one previous experience of being in the ICU. The average length of stay in the unit was 15 days. Of the participants, 38.5% lost their family member due to death during ICU hospitalisation. This is described in Table 4.

Characteristics of the respondents.

| Characteristics | N = 26 |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Age, X (SD) | 39 (13) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 23 (88.4) |

| Male | 3 (11.5) |

| City | |

| Medellín | 17 (65.4) |

| Manizales | 9 (34.7) |

| Kinship/affiliation | |

| Daughter/son | 11 (42.3) |

| Granddaughter/son | 5 (19.2) |

| Spouse | 4 (15.4) |

| Sibling | 3 (11.6) |

| Niece | 1 (3.9) |

| First cousin | 1 (3.9) |

| Father-in-law | 1 (3.9) |

| Profession/job | |

| Pensioner | 1 (3.9) |

| Housewife/housework | 1 (3.9) |

| Employed | 17 (6.4) |

| University student | 6 (23.1) |

| Living under the same roof | |

| Yes | 16 (61.5) |

| No | 10 (38.5) |

| Role during stay in ICU | |

| Family representative | 15 (57.7) |

| Accompanying the patient | 11 (42.3) |

| Role as caregiver prior to admission to ICU | |

| Yes | 6 (23.1) |

| No | 20 (76.9) |

| Experience prior to admission to ICU | |

| Yes | 4 (15.4) |

| No | 22 (84.6) |

| Length of stay in ICU | |

| Days X (SD) | 15 (12) |

| Death of relative in ICU | |

| Yes | 10 (38.5) |

| No | 16 (61.5) |

SD: standard deviation; ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

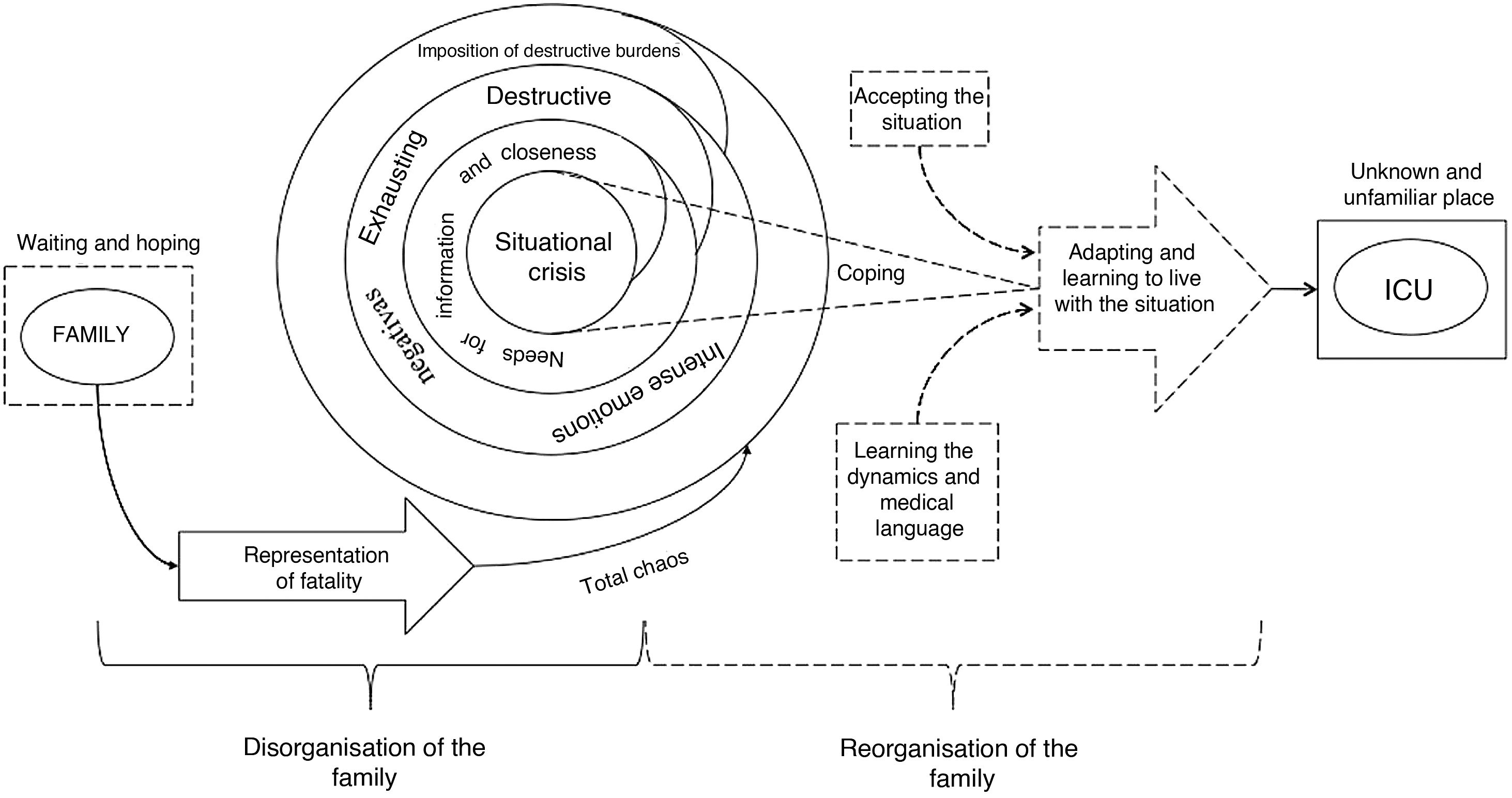

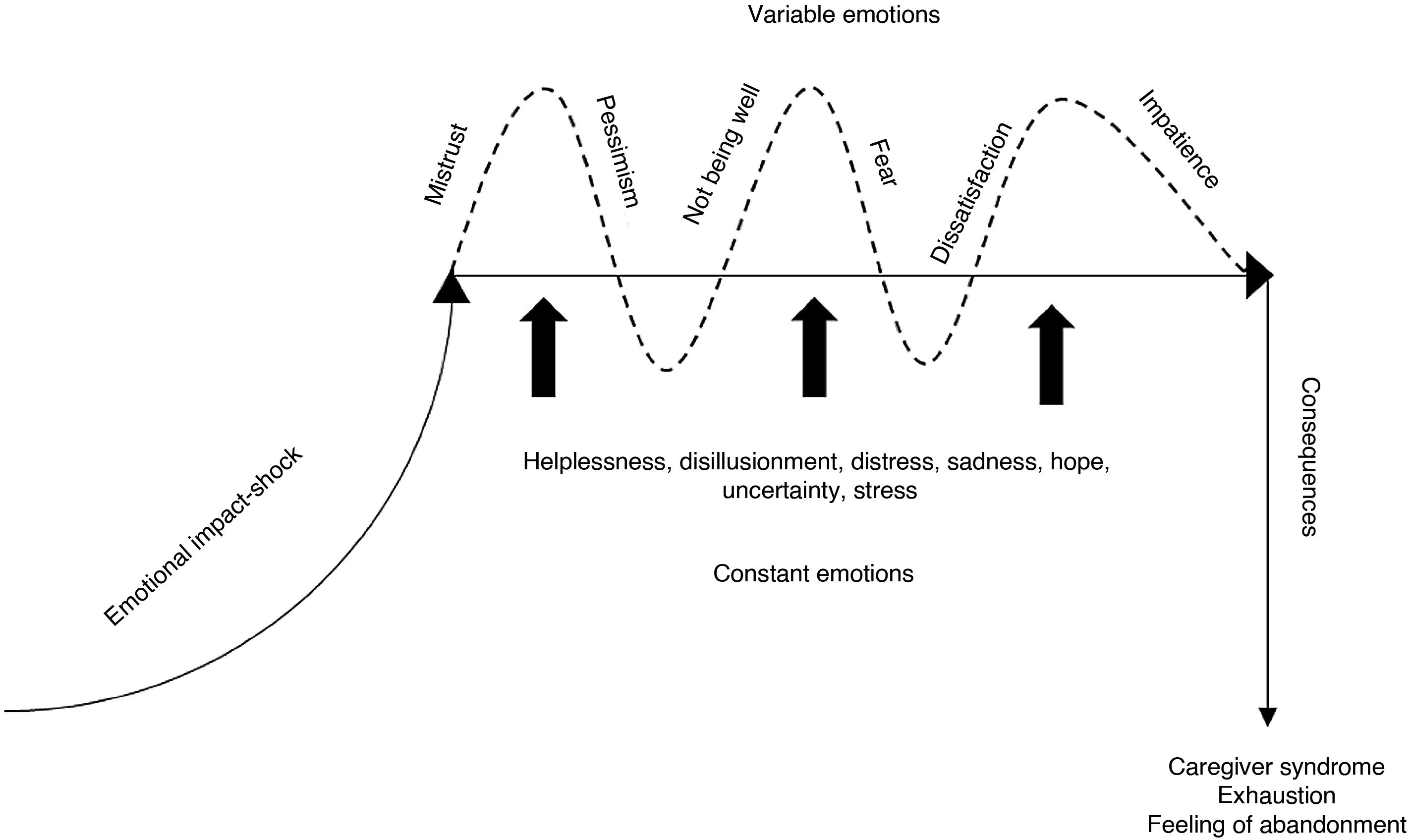

From the analysis of the data, we identified that the experience of family members in the ICU when accompanying their sick relative falls into 2 categories: "Family disorganisation" (as a situational crisis) and "Family reorganisation" (as a coping mechanism). This process is illustrated in Fig. 4 and described below.

The situations experienced by the relatives of patients in the ICU disorganise the family and cause them to enter a situational crisis. This crisis is related to the sudden and unexpected interruption and disruption of family dynamics, thus modifying the structure, roles, and expectations of its members.

The crisis is enhanced by the perception of fatality that family members have of the ICU, and is characterised by burdens imposed because of the condition of their sick relative and their stay in the ICU, emotional chaos and intense needs that lead to exhaustion.

Representations of the ICUThe relatives interpret the ICU as a threatening, risky and critical environment for the patient where "difficult" or "terrible" things can happen, even death, as can be seen from the following account: "(…) you always… what do you say… ICU… your hair stands on end, and you start to think about… terrible things" (EF19). This representation relates to aspects such as the patient being "connected to a lot of things and devices" (EF18) and that it is perceived as an imposing, technological and modern, but stressful place where many things can happen such as "getting worse" or "dying".

Similarly, some relatives consider the ICU an uncomfortable place, and represent it as a prison because it is closed, almost hermetic, and they must abide by a single authority, that of the institution, which imposes rules that everyone must strictly obey, even though these rules are sometimes difficult to understand and reconcile with the families’ daily dynamics. In this sense, the ICU behaves as a "total institution"31 which the relatives perceive as unknown and unfamiliar, as shown by the following comments: "(…) it’s a prison, that’s the saddest thing […] you’re outside all the time without being able to see anything and the windows are shut, so you don't even know how your relative is (…)" (EF11), "(…) I would say that intensive care units are more… are units that aren’t very comfortable for relatives" (EF13).

Likewise, relatives represent their experience in the ICU as "an upcoming storm" or as a "bucket of cold water". It is an unexpected situation in which the patient is drastically removed from their home to enter an unknown world, far from their loved ones and with multiple restrictions, as reflected in the following comment: "(…) but they tell you… you go to the ICU and it's like a storm comes over you and you kind of don't know, like, I'm not going to be able to be there, because you know that they have restrictions, that they have visiting hours, that they have… that they’re not going to have their television, their… or their little radio, or that they’re going to be, like, in another environment that will not be like being close to your home, but as far away from a home as you can get" (EF11).

Imposition of burdensOn the other hand, the admission of a patient to the ICU imposes responsibilities that the relatives perceive as burdens, since in addition to caring for their sick relative, they will have to take on something for which they have not been prepared and which demands a great physical, psychological, and emotional effort.

The main burden usually falls on the family member who is unemployed and has the time to accompany the patient, who lives with the patient or who had a caregiver role prior to their admission to ICU. This person generally has no replacement, and their functions include assuming what the patient wants, ensuring that the patient's will is upheld, establishing agreements with the doctors, and trying to ensure that the patient does not suffer physical harm. They usually provide permanent accompaniment or, if not, they attempt to remain as close to the patient as possible for as long as possible. Likewise, they take on the responsibility of being the family's information source as they are in charge of receiving news about the patient and communicating it to the outside world, explaining the situation and trying to help other family members understand what is happening.

This burden is often very great and difficult, therefore, especially when it involves having the last word in decisions made about the patient's care, for example, in end-of-life situations. This is how the following relative describes it: "(…) he said that he had gone into arrest and that there was nothing more to do, well… he asked if I wanted him to be resuscitated and I said no, so he said… ah well… then he died" (EF02).

While it is the right of the patient to make decisions, when they are critically ill, this is left to the family. Decisions made by family members are based on what they consider to be correct, representations of the ICU and its staff, emotions and needs derived from their experience and the limited information to which they have access, both regarding their relative's health problem and what is happening inside the unit. However, decisions are generally not freely made, but determined by when the unit staff decide to consult them.

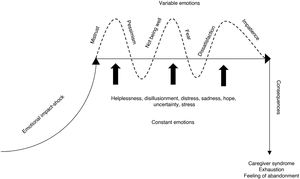

Emotions of relativesThe admission of a sick relative to the ICU and the stay in the unit unleashes multiple emotions and feelings which, when prolonged over time, wear down the relatives. As Fig. 5 shows, these emotions have levels of intensity and behave differently in the different phases of the process of disorganisation. Therefore, there is an onset or trigger of emotions, emotions that are constant and intense, emotions that vary in intensity and presentation, and implications or consequences that present in the advanced phase.

Onset is characterised by an impact and shock of multiple emotions that represent "total chaos", as can be seen in the following account: "(…) it was a super hard blow for my aunt… it triggered everything almost at that point, crying, sadness… everything… and for my cousin too (…)" (EF02).

During the stay in the ICU, there are constant and intense emotions such as helplessness, disappointment, anguish, sadness, hope, uncertainty, and tension. Simultaneously, as shown in Fig. 5, there are variable emotions and feelings such as fear, tension, longing, melancholy, impatience, dissatisfaction, pessimism, mistrust, and anger. The implications and consequences of these emotions are exhaustion and a feeling of abandonment, as reported by the following respondent: "(…) I think that my mother suffered caregiver burnout, really, it was very difficult for her because when my father recovered my mother was also very sick (…)" (EF05).

Based on the above, we recognise that the multiplicity of concerns, emotions and feelings coming together at the same time lead to the disorganisation of the family, as can be seen in the following testimony: "(…) I was angry, because I said… and I, but… why is this happening? […] there are so many things and I thought... if I am going to tell my son, that… well, there are so many things… so yes, there are too many emotions, too many feelings (…)" (EF16).

Needs of family membersAnother aspect representative of disorganisation is accentuated needs for information and proximity, which become intense, constant, and exhausting, which contributes to the situational crisis.

The need for information is the most pressing, constant, and distressing, as the following family member considers: "(…) to be told, at least to be told what… how I was (…)" (EF10).

The need for proximity is reflected in the intense desire to be in permanent contact with the patient while in the ICU. This need seems to be related to their attachment to the patient and the fear of losing their sick relative, as described: "(…) I don’t think I can live without him […] I’m too attached to him. Me to him and him to me (…)" (EF10).

The crisis resulting from disorganisation affects all family members and puts them in a position where their only alternative is to take action, which stimulates the reorganisation of the family to cope with the situation they are experiencing.

Family reorganisationThe situational crisis experienced by family members in the ICU generates a process of reorganisation that results in a family response, which is to cope with the situation and learn to overcome the obstacles that arise. The patient's situation saps the family's strength, which means that, to be strong, they must make an enormous effort not to succumb to the complexity of the situation.

There is a time therefore, when relatives become aware, identify, explore and reflect that what they are experiencing in the ICU is harmful for them and for the rest of the family, which encourages taking action to manage the situation, as evidenced in the following comment: "(…) I said. … yes, it may sound very selfish, but it is the truth… I have to look after the wellbeing and mental health of my son at the moment and in fact yes… so we left (…)" (EF16). To reorganise themselves, the families seek strength and courage to face the situation, struggling not to let themselves be consumed, as described by the following family member: "(…) in any case, you have to have the strength to move forward" (EF15).

To move forward in the face of adversity, there are family members who accept the situation they are going through and consider it part of life, and therefore they carry on with any limitations that may have arisen. Thus, they prepare for the worst, that is, they prepare for the possible imminent death of their sick relative: "(…) we have to be strong in the knowledge that she is going to leave us at any moment and first help her to go to her rest (…)" (EF15).

As part of preparing for the worst, relatives say goodbye and talk to the patient, asking and giving forgiveness for situations experienced, in an attempt to settle accounts and not leave anything pending, as indicated by the following relative: "(…) every day they promised him things, every day… as if trying to make him feel at peace and die (…)" (EF13). Similarly, they often look for support in spiritual and religious beliefs. In some cases, they believe that what happens is by divine design, as can be seen in the following testimony: "(…) that was what he had to live, that was what God had for him, and we as human beings cannot intervene in that (…)" (EF05).

They also take heart in the situation and try not to despair and be calm so as not to add more problems to what they are going through, as the following family members stated: "(…) he used to tell me… silly… let's cheer up, no, that man will get better… and I said… no man, I believe that he will get better (…)" (EF11), "(…) I didn’t want to give them another problem and I just swallowed it all by myself (…)" (E10). They also tend to talk with relatives of other patients, sharing common experiences of what they are going through and the situation of their sick relatives, as the following relatives relate: "(…) especially my aunts and my mother, well… the ladies talk to everyone and they started asking other relatives in the waiting room about what was wrong with their relative (…)" (EF06.

Similarly, they learn the dynamics of the health institutions and the ICU rules, and they appropriate the medical language to understand the situation and be on the same level as the unit's staff. This is part of a process of socialisation and enculturation that allows families to take some control over their surrounding environment and help them to interact more fluidly with it. This is facilitated when the patient has a history of multiple admissions to the hospital and ICU, as described by the following family respondent: "(…) so many admissions and discharges from the hospital, I was kind of familiar with hospitals (…)" (EF19).

To move forward in the face of adversity, there are family members who are resigned to the situation they are going through and consider it part of life, and therefore they carry on with the limitations that may have arisen, as described by the following family member: "Well, well, it is difficult, but we have managed to get through it" (EF09).

Relatives manage to learn to overcome what they experience when they adapt, get used to and learn to coexist with the burdens, emotions, needs and new family dynamics derived from the stay in the ICU, as observed in the following account: "And with my work I’ve been able to overcome it because I have my days of domestic calamity, I go out and I can be with him and I can attend to work, I can attend to my home and well… and you have to know how to cope with life" (EF08).

After this experience, they tend to appreciate and enjoy life more, living each day to the full, as a family member said: "(…) you have to live life as if it were the last day of life… because you don't know what’s going to happen… so, that's why you have to love intensely… feel loved, be very happy, show what you feel… that is, not repress like anything…. you see, it's like you often keep quiet… no, how am I going to say… how am I going to feel? (…)" (EF16). In this respect, a capacity for resilience can be seen in the family members to transform their complex and difficult experience into positive and significant learning for their lives.

DiscussionThe journey or transition of the family through the ICU, from the analytical point of view, can be interpreted as a process with 2 phases, a first phase of disorganisation/destabilisation represented by the situation and all the movement generated by the family's stay in the ICU, imposing burdens and producing intense and exhausting needs and emotional states. A second stage of reorganisation occurs as a form of response, resolution, and readjustment, which makes it possible to cope with the situation and learn to overcome obstacles.

Our findings coincide with those of Fernández et al.,32 who state that an illness represents a radical change in the functioning and composition of the family, which can be considered a crisis of disorganisation that inevitably impacts each of its members, including people outside the family. Likewise, Koulouras et al.10 state that the family's suffering due to the admission of their sick relative to ICU is represented by emotions and feelings that may jeopardise the health of relatives or the cohesion and stability of the family.

In line with other studies,13,15,33–37 having a critically ill loved one in ICU is a source of high levels of distress and anxiety, given the unknowns derived from the severity of the patient, the feeling that everything happens quickly and the pressures associated with this situation.11 In this respect, Breisinger et al.12 state that anxiety can make it difficult to understand what happens when a person is faced with a new and unfamiliar situation such as that experienced by relatives when they are admitted to an ICU, as evidenced by the respondents in this research study.

However, Noome et al.,38 identified that relatives in the ICU may experience the decision-making process as problematic, especially when there are difficulties in communicating with healthcare staff. This is consistent with the findings of our study in which relatives perceive decision-making as a burden and as a process determined by the unit staff.

In this regard, De Beer and Brysiewicz7 argue that providing information promptly and making decision-making a shared process gives relatives confidence, reassures them and makes them grateful to staff, gives meaning to their presence and a feeling of being in control of the situation.39,40 Some factors that facilitate decision-making for relatives include allowing them to perform their own rituals during the dying process, perceiving that the staff is interested in them, establishing good communication with the healthcare team, becoming more involved in the patient's care, and reducing the anxiety derived from the situation they are experiencing.35,38,41

Frivold et al.15 found that the possibility of death surrounding the sick relative generates stress in the family member, which coincides with the findings of this study. This situation, if not promptly dealt with and without adequate treatment, can make family members more likely to develop post-traumatic stress.9,13,15,35 Therefore, the concept of "Post-ICU Syndrome Family (PICS-F)" has been proposed to describe the impact and negative consequences that the ICU generates on family members experience in the unit accompanying their sick relative.23 Therefore, the situational crisis experienced by the family members who participated in this study may be a risk factor for developing PICS-F.

NANDA International42 recognises that the family may have 2 problems, which it presents through the nursing diagnoses: “dysfunctional family processes” and “impaired family processes”.43 The former is defined as “family functioning which fails to support the well-being of its members”; and the latter as “a break in the continuity of family functioning which fails to support the well-being of its members”. Therefore, this study proposes the concept of situational family crisis, which represents a disruption of family dynamics that encourages a process of reorganisation which, in turn, encourages the development of strategies and the resignification of their experience to cope with the situation they are experiencing.

It is recognised that empathy and understanding towards relatives and the communication skills and strategies of the nurses working in the ICU need to be improved.35,44,45 Taking the family into account in ICU care plans favours better communication and understanding of the patient, and reduces anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress among relatives.46–50

Regarding family reorganisation, Bohorquez de Figueroa et al.,51 state that families have their own daily dynamics. However, families in the ICU change these dynamics to reorganise themselves and adapt to the complexities involved in having a sick relative in the unit. This coincides with the actions taken by the family members in this study as a coping mechanism to deal with the crisis they face.

In line with the study by Warren et al.,52 as part of the reorganisation process, relatives learn the medical language, rules, and culture of the units, which is influenced by previous experiences or by an active search for information to learn more about the dynamics of the unit.

In addition to the above, family reorganisation occurs as a way of coping with the situation since, as Lazarus and Lazarus53 state, coping strategies are generated when learning to manage emotions once they have been aroused, as well as the worrying situations that trigger them. It was identified that family members, during the reorganisation process, learn to move forward amid the burdens, emotions and needs arising from the stay in ICU.

This study identified that, based on the situational crisis and the reorganisation process aimed at re-establishing family order, family members establish a logic of behaviour within the unit. Maturana and Varela54 argue that living beings are autopoietic machines, as they transform matter in themselves, in such a way that its product is their own organisation. According to the authors, these machines are homeostatic and organised, and generate relationships that arise from continuous interactions and transformations. Thus, these machines "specify and produce their own organisation through the production of their own components, under conditions of continuous perturbation and compensation of these perturbations.”

A limitation of the study is that it was conducted in closed ICUs with restricted hours for family access, as it is possible that the results might vary if the study had been performed with family members with experience in units or institutions with policies or processes of care aimed at the humanisation of services and PFCC. Likewise, for future studies along the same lines, interviewing several members of the patient's family group is recommended, as interviewing only one member of the family reflects the family’s experiences from the perspective of that member alone.

Another limitation of the study is that it was designed and developed from the perspective of the nursing discipline, which means that the results contribute in the main to improving nursing care practice in ICU. However, it is recognised that family care is the responsibility of all members of the healthcare team working in the ICU and can benefit from an interdisciplinary approach and support.

As future lines of research, we propose that the concept of situational family crisis, which has the potential to become a nursing diagnosis, be explored in greater depth. Similarly, studies can be developed along specific lines such as the emotional intelligence of ICU nurses in relation to the care of family members and their relationship to meeting needs, and the development of PTSD and PICS-F.

Similarly, we suggest going deeper into the representations of the ICU associating it, on the one hand, with the symbolic interpretation that family members make of the spaces, staff, and physical resources of the unit and, on the other, with the impact that it has on the functionality of the family and on the emotional dimension of each of its members.

ConclusionsThe journey of a family member through the ICU when accompanying a sick relative develops in 2 sub-processes, that of disorganisation and that of family reorganisation. In the former, multiple emotions, feelings and needs are unleashed which, if prolonged over time, wear down the family members. These emotions and needs seem more intense, varied, and negative than in other hospital units. In the latter, relatives seek to re-establish order in the family dynamics to cope with the situation and overcome the difficulties caused by the admission of their sick relative to the ICU.

The strategies that the relatives used to re-establish order were to identify and become aware of what could be harmful to them, to consider the situation they are living through as part of life, to say goodbye, to settle accounts with the patient and prepare for the worst, to take heart in the situation and not to despair, and to learn the medical language and dynamics of the unit and the institution. Likewise, in the process of reorganisation, the resilience of family members helps them develop positive learning for their own lives.

FundingThe authors declare that no funding was provided for this paper.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Duque-Ortiz C, Arias-Valencia MM. La familia en la unidad de cuidados intensivos frente a una crisis situacional. Enferm Intensiva. 2022;33:4–19.