To evaluate the degree of implementation of protocols associated with the prevention of intensive-care-unit (ICU) acquired muscle weakness, and the presence of the physiotherapist in various ICU in Spain.

MethodA descriptive, cross-sectional study performed in 86 adult ICU in Spain between March and June 2017. Neurosurgical and major burns ICU were excluded. A multiple-choice survey was used that included questions on protocols for glycaemia control, sedation, pain assessment, delirium prevention, delirium management and early mobilisation. The survey was completed using a user-protected application and password. The Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test and Pearson's correlation or Spearman's Rho test were used for the inferential analysis.

ResultsEighty-nine point five percent of the ICU had a glycaemia control protocol, with a predominating range of 110–140mg/dl. Seventy-four point four percent evaluated sedation levels, although only 36% had sedation protocols. Pain assessment was carried out on communicative patients in 73.7%, and on uncommunicative patients in only 47.5%. Only 37.2% performed daily screening to detect delirium and 31.4% of the ICU had delirium prevention protocols, 26.7% had delirium management protocols and 14% had protocols for early mobilisation. Thirty-four point nine percent requested cross consultation with the rehabilitation department.

ConclusionsThe implementation of the different protocols associated with the prevention of ICU-acquired muscle weakness was high in relation to glycaemia control protocols, sedation level and pain assessment in communicative patients, and was low for early mobilisation and delirium screening and prevention. Similarly, the physiotherapist was seldom present in the ICU.

Evaluar el nivel de implementación de los protocolos asociados a la prevención de la debilidad muscular adquirida en la unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI), así como la presencia del fisioterapeuta en distintas UCI de España.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo, transversal realizado en 86 UCI de adultos de España entre los meses de marzo a junio de 2017. Se excluyeron UCI neuroquirúrgicas y de grandes quemados. Se utilizó encuesta multirrespuesta que incluía preguntas sobre los protocolos de: control de glucemia, sedación, valoración del dolor, prevención del delirium, manejo del delirium y movilización precoz. La encuesta fue rellenada a través de un aplicativo protegido por usuario y contraseña. Análisis inferencial con t de Student o U de Mann-Whitney y de correlación con Pearson o Rho de Spearman.

ResultadosEl 89.5% de las UCI tenían protocolo de control de glucemia, con rango predominante de 110-140mg/dl. El 74,4% evaluaban el nivel de sedación, si bien solo tenían protocolos de sedación el 36% de ellas. Con relación a la valoración del dolor se realizaba en el 73,7% de los pacientes comunicativos, mientras que en los no comunicativos solo era del 47,5%. Solo el 37,2% realizaban screening diario para detectar el delirium, y disponían de protocolos de prevención del delirium el 31,4% de las UCI, del manejo del delirium el 26,7% y de movilización precoz el 14% de las UCI. En el 34,9% de los casos se solicita interconsulta al servicio de rehabilitación.

ConclusionesLa implementación de los diferentes protocolos asociados a la prevención de la debilidad muscular adquirida ha sido elevada en relación con los protocolos de control de glucemia, valoración del nivel de sedación y del dolor de pacientes comunicativos, mientras que baja en los de movilización precoz y screening y prevención del delirio. Asimismo, es poco frecuente la presencia del fisioterapeuta en la UCI.

The benefits of early mobilisation (between day 2 and 5 following admission to ICU) that reduce the incidence and sequelae of ICU-acquired weakness (ICUAW) seldom apply in daily practice, largely due to analgo-sedation practices that do not comply with current recommendations The functions of the physiotherapist and their available time also vary greatly between countries.

This study shows that there is little implementation of algorithm-guided analgo-sedation protocols or the early detection of delirium, associated with the early mobilisation of patients. However, we did observe greater implementation of hyperglycaemia control, a risk factor for ICUAW. Physiotherapists are involved in ICU by consultation with the rehabilitation department, since they are rarely part of the team in ICUs. This can delay the start of mobilisation, resulting in its not being delivered promptly.

Implications of the study?It is not advisable to implement mobilisation protocols in ICU without having first agreed analgo-sedation and delirium prevention protocols with the interprofessional team (adding the physiotherapist, but as a consultant at first) to ensure that the patient is awake, collaborating and pain free for mobilisation, in bed initially (cyclo-ergonometry for example) until they have gained trunk control to be able to stand and walk.

Advances in the treatment and care of critical patients have increased survival after discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU),1 redirecting our care objectives towards a more demanding goal: achieving improved quality of life after hospitalisation.2

Post ICU syndrome is defined as the physical, functional and cognitive loss of patients who have been admitted to ICU that affects their return to work. Forty-five percent of these patients return within the first year, and 17% die.3,4

Intensive Care Unit Acquired Weakness (ICUAW) is one of the most studied aspects of this syndrome, which can be diagnosed in between 26% and 65% of patients 5 and 7 days after starting mechanical ventilation, respectively.5,6 ICUAW comprises the atrophy and/or loss of muscle mass as a consequence of myopathy, polyneuropathy or both at once, with no other explanatory aetiology than the critical disease itself. The degree of comorbidity, days of mechanical ventilation and length of stay in ICU, a diagnosis on admission of sepsis, muscle relaxants and corticosteroid administration, hyperglycaemia and multi-organ failure are risk factors for developing ICUAW; there are different levels of evidence among these.7,8

Several studies published in the last decade and a recently published systematic review9 have identified the efficacy of early mobilisation to prevent and/or reduce the sequelae related to post-ICU syndrome. Based on these studies, early mobilisation has been defined as the physical activity undertaken between day 2 and 5 of admission to ICU or during the first 3 days following admission. These experimental studies are based on the combination of active exercises for critical patients, with greater or lesser degrees of mobility, and on the implementation of analgo-sedation protocols or daily interruption of sedation that encourage light sedation and consciousness, necessary for the patient to be able to cooperate and move actively.

Furthermore, some studies also add glycaemic10 control to the intervention group because, as we mentioned earlier, hyperglycaemia is associated with a higher risk of ICUAW.11,12

More recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of early mobilisation to reduce the incidence of delirium in critical patients, which has been quantified at between 32% and 44%.13,14 Finally, an expert consensus statement on the rehabilitation of the critical patient,15 concludes that pain control is essential to achieve optimal mobilisation, and therefore reduce the adverse effects of bedrest,8 which are more severe with age. This factor should be taken into account due to the marked ageing of the population admitted to ICU that is currently recorded.16

It is precisely this change, the older age of critical patients, which is the cause of the principal methodological weakness of the studies that promote early mobilisation: inclusion and exclusion criteria that are very restrictive in terms of baseline functional capacity prior to admission to ICU. This seriously limits the external validity of experimental studies on the benefits of early mobilisation, given the high number of patients who cannot participate in studies because, in general, the greater their age the poorer their functional capacity. Schweickert,10 who set a benchmark in mobilisation, excluded 87% of patients.

If we consider the ageing of the critical patients currently admitted to ICU, and therefore their greater comorbidity and frailty,16 this percentage given by Schweickert10 could be even higher in this decade. Therefore it is becoming more important to assess comorbidity rather than severity in clinical trials, because it is a good predictor of the risk of readmission to ICU3 and relates better to the incidence of ICUAW.15,17

Most clinical trials on early mobilisation have been completed on relatively healthy critical patient populations,10,18 there are few studies on surgical patients,18,19 single-centre studies predominate over multi-centre studies,9 and the number of patients included with sepsis varies, there being more controversy regarding the benefits of early mobilisation for this subpopulation.20

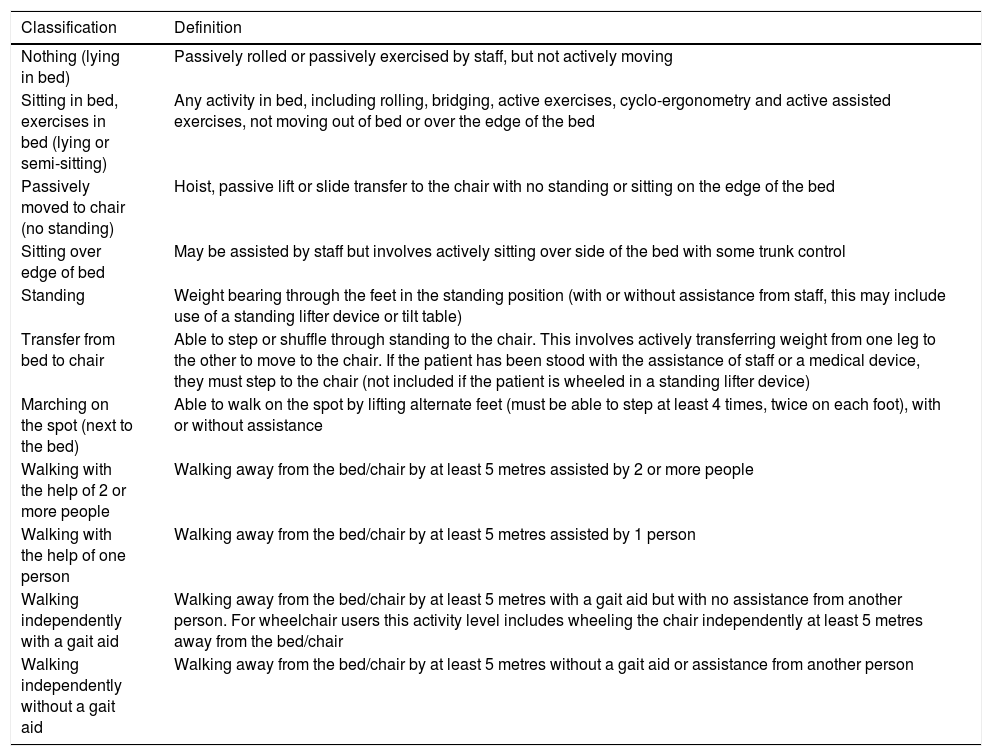

Another shortcoming, this time in terms of internal validity, is the lack of information on sedation and weaning protocols applied to the control group: between 88% and 96% do not detail them.8,9 The authors of Team Study Investigators,21 observed that early mobilisation (scores from 1 to 10 on the ICU Mobility Scale, Table 1) was only possible for 70 (36.5%) of the 192 patients analysed, because the rest were too sedated to be able to collaborate in mobilisation on the 1st and 2nd days following admission to ICU, and 30% of them were still in this condition on the 3rd and 4th days.

ICU mobility scale (ICUMS).

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Nothing (lying in bed) | Passively rolled or passively exercised by staff, but not actively moving |

| Sitting in bed, exercises in bed (lying or semi-sitting) | Any activity in bed, including rolling, bridging, active exercises, cyclo-ergonometry and active assisted exercises, not moving out of bed or over the edge of the bed |

| Passively moved to chair (no standing) | Hoist, passive lift or slide transfer to the chair with no standing or sitting on the edge of the bed |

| Sitting over edge of bed | May be assisted by staff but involves actively sitting over side of the bed with some trunk control |

| Standing | Weight bearing through the feet in the standing position (with or without assistance from staff, this may include use of a standing lifter device or tilt table) |

| Transfer from bed to chair | Able to step or shuffle through standing to the chair. This involves actively transferring weight from one leg to the other to move to the chair. If the patient has been stood with the assistance of staff or a medical device, they must step to the chair (not included if the patient is wheeled in a standing lifter device) |

| Marching on the spot (next to the bed) | Able to walk on the spot by lifting alternate feet (must be able to step at least 4 times, twice on each foot), with or without assistance |

| Walking with the help of 2 or more people | Walking away from the bed/chair by at least 5 metres assisted by 2 or more people |

| Walking with the help of one person | Walking away from the bed/chair by at least 5 metres assisted by 1 person |

| Walking independently with a gait aid | Walking away from the bed/chair by at least 5 metres with a gait aid but with no assistance from another person. For wheelchair users this activity level includes wheeling the chair independently at least 5 metres away from the bed/chair |

| Walking independently without a gait aid | Walking away from the bed/chair by at least 5 metres without a gait aid or assistance from another person |

The scale was translated into Spanish from the original by Hodgson et al.,49 with the permission of the author, following expert recommendations to ensure that the instrument was equivalent in terms of semantics, concept, technical content and criteria in different languages. It is in the process of validation and transcultural adaptation by the investigating team of this manuscript.

The variables that interprofessional teams use to decide the level of mobilisation that can be applied to the patients are not well defined in the protocols of these studies either.9

For all the above reasons, it makes little sense to implement an early mobilisation protocol in an ICU whose daily practice does not include protocolised management of sedation, pain and delirium, or hyperglycaemia control protocols updated according to the latest recommendations.22,23

ObjectiveTo assess the level of implementation of the protocols associated with the prevention of ICUAW, and the presence of the physiotherapist in various ICU in Spain.

MethodologyA descriptive, cross-sectional study performed in adult ICU in Spain between March and June 2017. Eighty-six ICU were included of the 229 ICU (37.5%) that routinely participate in the ENVIN-HELICS registry (bacteraemia zero and/or pneumonia zero), a national benchmark programme for assessing actions implemented in ICU. Major burns and neurosurgical ICU were excluded from this census; they were not considered in this study as the indication for mobilisation of these patients is markedly different due to their specific clinical features.

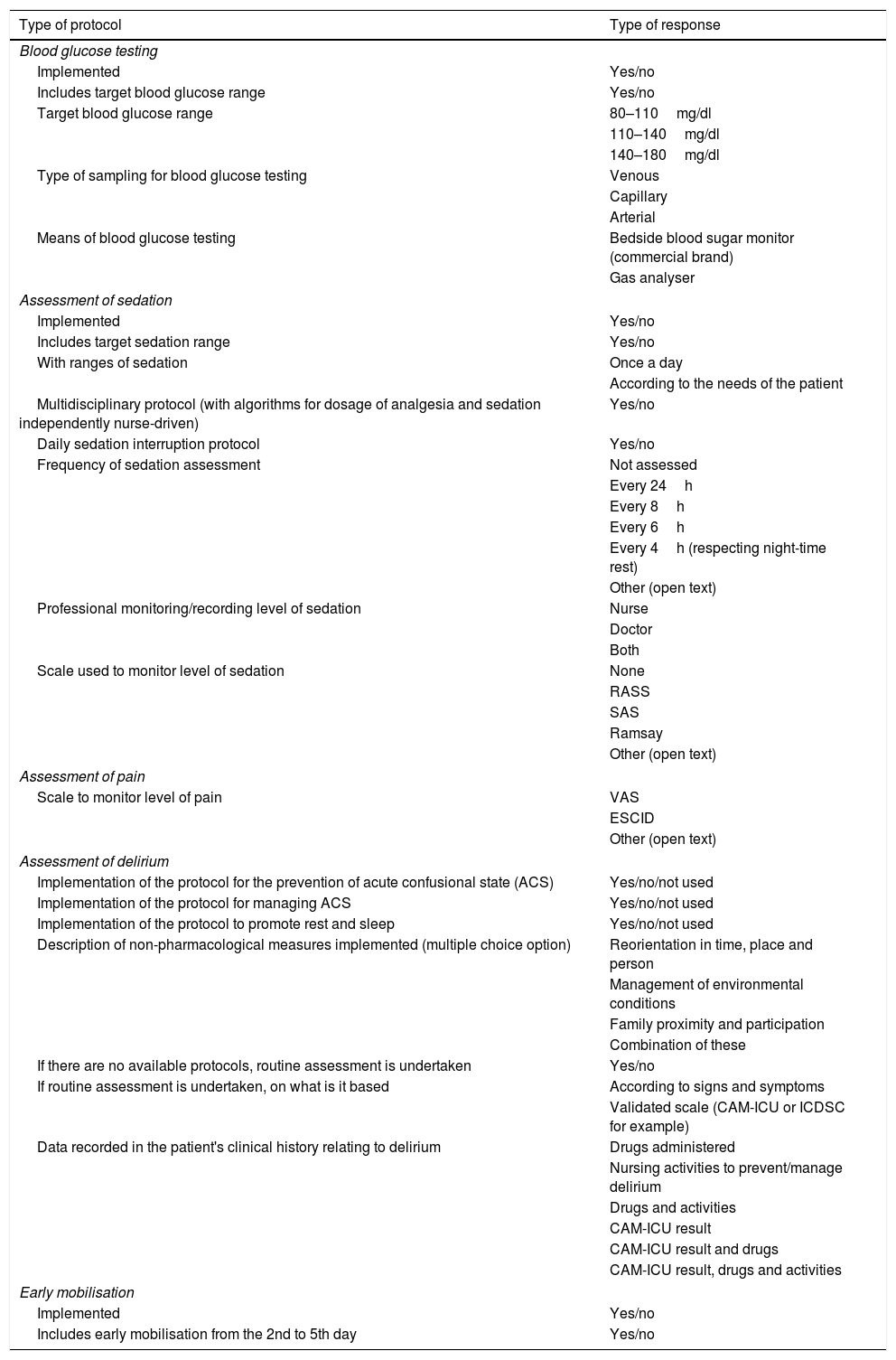

In order to evaluate the variability in implementing protocols among the different ICU, the Spanish Society of Intensive Care and Coronary Unit Nursing (SEEIUC) promoted the project to include the maximum amount of autonomous regions, and different types of hospitals and units. Data related to the human resources available for mobilising patients were recorded (nurse: patient ratios and hours with/of physiotherapy in the unit) and qualitative variables to analyse how the recommendations of the latest clinical guidelines for the management of sedoanalgesia and delirium are implemented.24,25 An online application was designed, to which the principal investigator of each unit participating in the study had access by username and password (one nurse per ICU) with multiple choice questions and, in some, the possibility of open text (Table 2). A pilot test was performed beforehand to assess its viability, facial validity and test–retest intraobserver reliability.

Variables of the study relating to the prevention of post-ICU syndrome.

| Type of protocol | Type of response |

|---|---|

| Blood glucose testing | |

| Implemented | Yes/no |

| Includes target blood glucose range | Yes/no |

| Target blood glucose range | 80–110mg/dl |

| 110–140mg/dl | |

| 140–180mg/dl | |

| Type of sampling for blood glucose testing | Venous |

| Capillary | |

| Arterial | |

| Means of blood glucose testing | Bedside blood sugar monitor (commercial brand) |

| Gas analyser | |

| Assessment of sedation | |

| Implemented | Yes/no |

| Includes target sedation range | Yes/no |

| With ranges of sedation | Once a day |

| According to the needs of the patient | |

| Multidisciplinary protocol (with algorithms for dosage of analgesia and sedation independently nurse-driven) | Yes/no |

| Daily sedation interruption protocol | Yes/no |

| Frequency of sedation assessment | Not assessed |

| Every 24h | |

| Every 8h | |

| Every 6h | |

| Every 4h (respecting night-time rest) | |

| Other (open text) | |

| Professional monitoring/recording level of sedation | Nurse |

| Doctor | |

| Both | |

| Scale used to monitor level of sedation | None |

| RASS | |

| SAS | |

| Ramsay | |

| Other (open text) | |

| Assessment of pain | |

| Scale to monitor level of pain | VAS |

| ESCID | |

| Other (open text) | |

| Assessment of delirium | |

| Implementation of the protocol for the prevention of acute confusional state (ACS) | Yes/no/not used |

| Implementation of the protocol for managing ACS | Yes/no/not used |

| Implementation of the protocol to promote rest and sleep | Yes/no/not used |

| Description of non-pharmacological measures implemented (multiple choice option) | Reorientation in time, place and person |

| Management of environmental conditions | |

| Family proximity and participation | |

| Combination of these | |

| If there are no available protocols, routine assessment is undertaken | Yes/no |

| If routine assessment is undertaken, on what is it based | According to signs and symptoms |

| Validated scale (CAM-ICU or ICDSC for example) | |

| Data recorded in the patient's clinical history relating to delirium | Drugs administered |

| Nursing activities to prevent/manage delirium | |

| Drugs and activities | |

| CAM-ICU result | |

| CAM-ICU result and drugs | |

| CAM-ICU result, drugs and activities | |

| Early mobilisation | |

| Implemented | Yes/no |

| Includes early mobilisation from the 2nd to 5th day | Yes/no |

The categorical variables were expressed in frequencies and percentages, using the Fisher's or chi-squared test to compare between groups. The results of the quantitative variables were expressed in means and standard deviation (SD) or medians and interquartile range, depending on normality, and the groups were compared using the Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. The correlation between quantitative variables was analysed using Pearson's or Spearman's rho coefficient, according to the distribution of the data. A p value below .05 was deemed statistically significant. SAS1 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.) was used for the analysis.

Ethical aspectsThe recommendations were followed of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and the 1997 Oviedo Convention, Law 15/1999 regulating automated personal data processing.

Each hospital was assigned a code, generated by the investigator coordinating the study, which was made known to the centre's principal investigator alone, ensuring data confidentiality and anonymity. The approval of all the participating centres’ Clinical Research Ethics Committees was obtained to undertake the study.

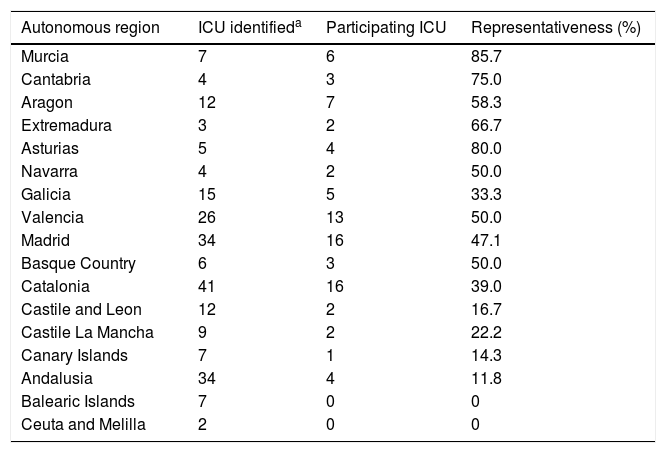

ResultsThe most represented autonomous regions were Murcia, Asturias and Cantabria, and the least represented were the Canary Islands and Andalusia, and there was no representation in the Balearic Islands, Ceuta and Melilla (Table 3).

Representativeness of the units surveyed according to autonomous region.

| Autonomous region | ICU identifieda | Participating ICU | Representativeness (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Murcia | 7 | 6 | 85.7 |

| Cantabria | 4 | 3 | 75.0 |

| Aragon | 12 | 7 | 58.3 |

| Extremadura | 3 | 2 | 66.7 |

| Asturias | 5 | 4 | 80.0 |

| Navarra | 4 | 2 | 50.0 |

| Galicia | 15 | 5 | 33.3 |

| Valencia | 26 | 13 | 50.0 |

| Madrid | 34 | 16 | 47.1 |

| Basque Country | 6 | 3 | 50.0 |

| Catalonia | 41 | 16 | 39.0 |

| Castile and Leon | 12 | 2 | 16.7 |

| Castile La Mancha | 9 | 2 | 22.2 |

| Canary Islands | 7 | 1 | 14.3 |

| Andalusia | 34 | 4 | 11.8 |

| Balearic Islands | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Ceuta and Melilla | 2 | 0 | 0 |

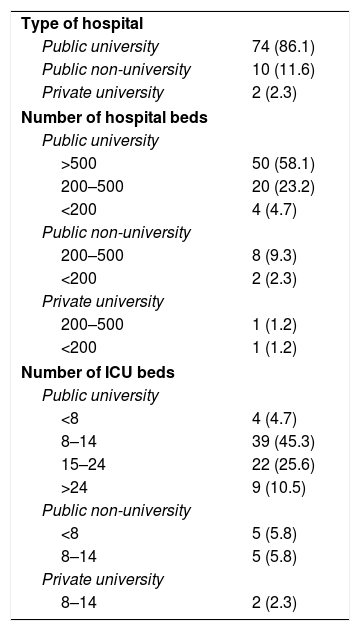

Of the 86 ICU participating in the study, 84 (97.7%) belonged to public hospitals, 76 (88.4%) were in university hospitals, of which 50 had more than 500 beds (Table 4). Polyvalent ICU predominated (75.6%), with only 7% surgical resuscitation ICU, 5.8% were exclusively medical, and 4.7% were coronary and heart surgery ICU, respectively. ICU specialising in trauma were the least represented (2.3%). The most frequent size of the ICU was between 8 and 14 beds, 36.1% had more than 14 beds (Table 4).

Characteristics of the hospitals and units included in the study (n, %).

| Type of hospital | |

| Public university | 74 (86.1) |

| Public non-university | 10 (11.6) |

| Private university | 2 (2.3) |

| Number of hospital beds | |

| Public university | |

| >500 | 50 (58.1) |

| 200–500 | 20 (23.2) |

| <200 | 4 (4.7) |

| Public non-university | |

| 200–500 | 8 (9.3) |

| <200 | 2 (2.3) |

| Private university | |

| 200–500 | 1 (1.2) |

| <200 | 1 (1.2) |

| Number of ICU beds | |

| Public university | |

| <8 | 4 (4.7) |

| 8–14 | 39 (45.3) |

| 15–24 | 22 (25.6) |

| >24 | 9 (10.5) |

| Public non-university | |

| <8 | 5 (5.8) |

| 8–14 | 5 (5.8) |

| Private university | |

| 8–14 | 2 (2.3) |

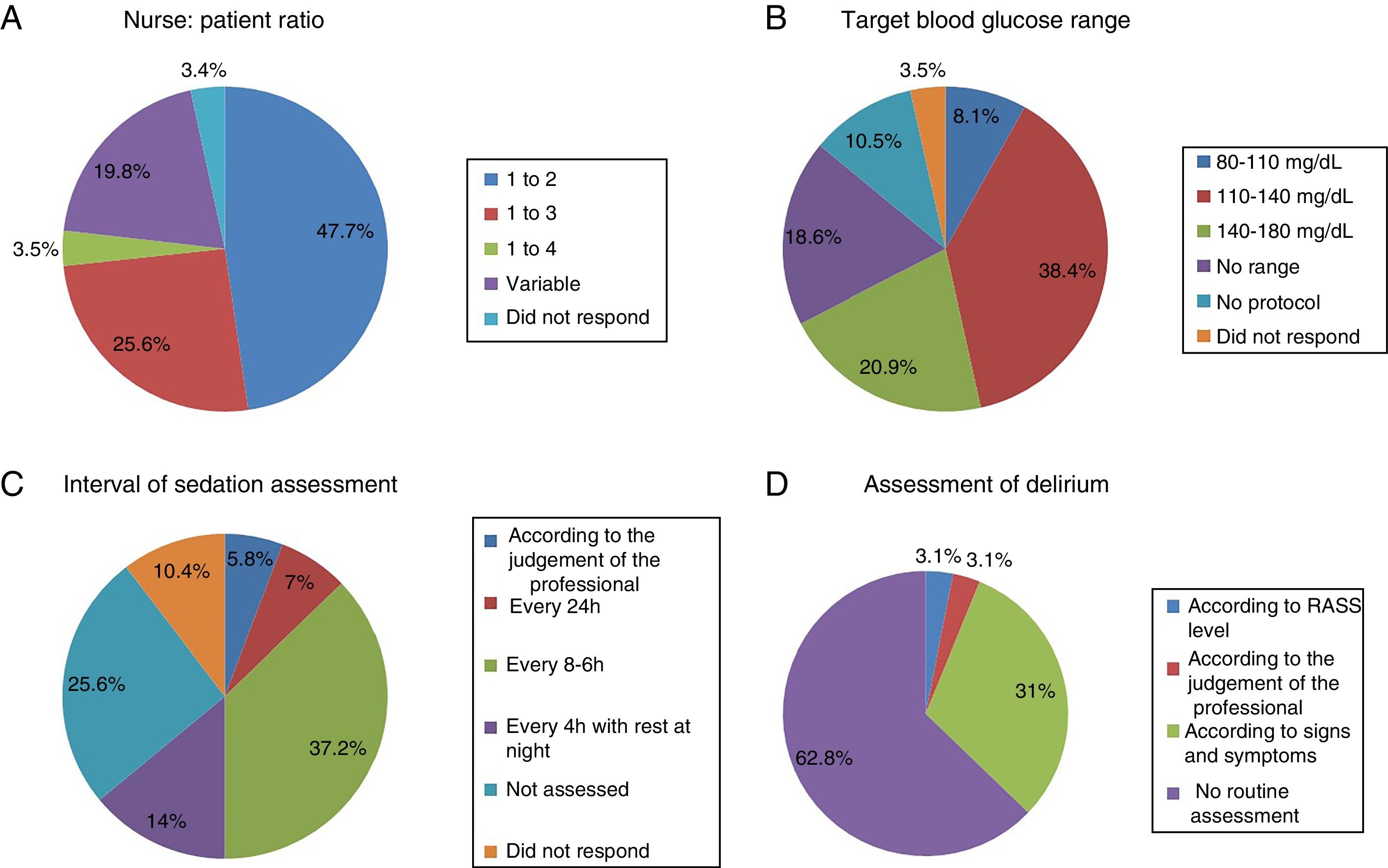

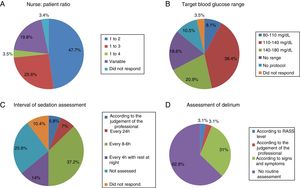

The most common nurse: patient ratio was 1:2 in 47.7% of the ICU (Fig. 1A). In others it varied according to the shift (day, night and weekend) or to the area of the ICU where the nurses were located, principally semi-critical care units. A ratio of 1:3 was more common in non-university hospitals than in university hospitals but with no significant difference (18 [24%] vs.4 [50%], p=.2).

Physiotherapy serviceEighteen point six percent of the ICU did not have a physiotherapist as part of the ICU team, 10.5% had fewer than 5h of physiotherapy per week, 12.8% had between 5h and 10h, 10.5% between 10h and 15h, 8.1% 20h, and only 4.6% more than 24h. The remaining 34.9% had physiotherapy via consultation with the rehabilitation department.

Although the available physiotherapy time in non-university hospitals was lower compared to university hospitals, this difference was not significant (8.75h vs. 3.20h, difference from the mean 5.5h 95%CI [−3.8–14.9]). The greater number of physiotherapy hours in some units was did not relate to a greater number of beds (r=.2, p=.08).

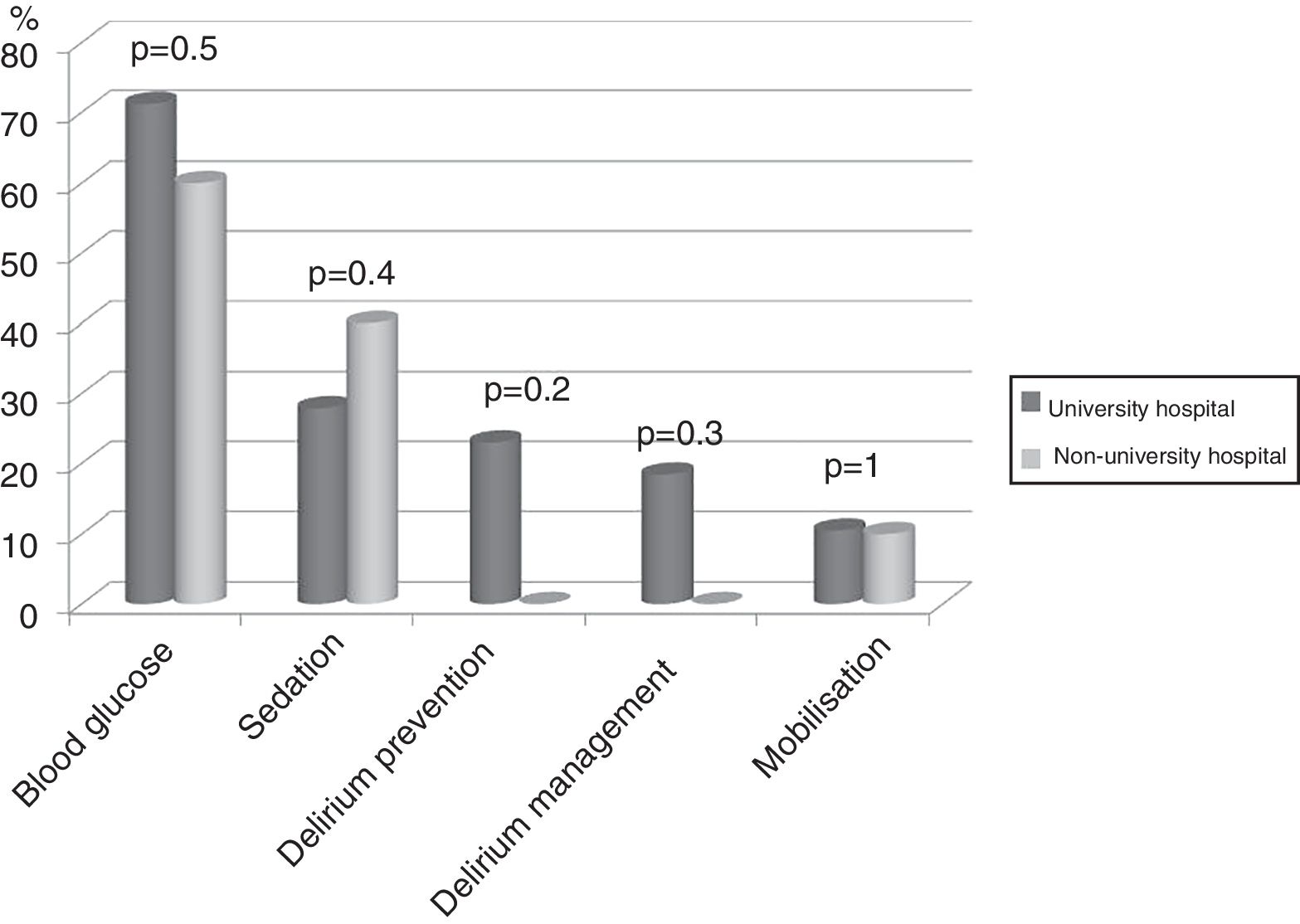

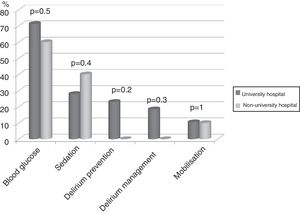

Seventy-four (86%) ICU had no mobilisation protocol, with no differences between university and non-university hospitals. Furthermore, in 3 (3.5%) of the ICU that did have a protocol, it did not cover early mobilisation, i.e., during the first 5 days following admission to the ICU. There were no differences either between the type of hospital in relation to the remaining protocols analysed (Fig. 2).

Blood glucose analysisNine (10.5%) ICU had no protocol for blood glucose control, and of those who did, the target range of 110–140mg/dl predominated (Fig. 1B).

Seventy-four (86%) of the units analysed blood glucose by capillary blood sampling, and 80 (93%) by a bedside blood glucose metre. The most usual commercial brands were Accu-Chek® (23.3%), Abbott Freestyle® (12.8%), True Result® from Medical (7%), and Nova Pro® from Menarini (5.8%). Three point five percent used StataStrip® from Novabiomedical.

Assessment of sedationFifty-five (64%) of the ICU had no sedation protocol, and of these 22 (81.5%) units did not prescribe an optimal range of sedation. Among the ICU that used sedation protocols, this was multidisciplinary in only 13 units with algorithms for nurses to guide analgo-sedation autonomously, whereas 10 units (11.6%) used daily interruption of sedation.

Sedation levels were not monitored in 22 ICU (25.6%). In the ICU that regularly assessed sedation, the assessment interval varied greatly (Fig. 1C). The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) was used most to evaluate sedation (56 ICU, 65.1%), the Ramsay Sedation Scale (10, 11.6%) and Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS) (2, 2.3%) were used far less. Eleven (12.8%) ICU used no scale at all to assess sedation.

Nurses evaluated sedation in the majority of the ICU, the comparison with ICU where it was evaluated by doctors was significant (45 [52.3%] vs. 9 [10.5%], p<.001). Both professionals evaluated sedation interchangeably in 15 (17.4%) units.

Assessment of painPain was assessed using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for communicative patients in 59 (73.7%) of the units, whereas the pain of uncommunicative patients was assessed in only 38 (47.5%) of the units, using the Scale of Behaviour Indicators of Pain (ESCID).

Assessment of deliriumOnly 32 (37.2%) units screened all patients for delirium, although with considerable disparity in criteria (Fig. 1D).

Twenty-two (68.8%) units used a validated scale, Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit or Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC), although only 7 (31.8%) of the units responded that they recorded the results of the assessment.

Fifty-nine (68.6%) units did not have delirium prevention protocols, and 63 (73.3%) ICU did not have protocols to manage established delirium either. Of the units with protocols for the prevention and management of delirium, 5 (7.8%) and 3 (4.6%), respectively, acknowledged that they did not use them. Irrespective of whether or not they had delirium prevention and/or management protocols, non-pharmacological interventions were used by nurses in 29 (33.7%) of the ICU.

Of these units (56, 65.1%) the combination of reorientation in time, place and person predominated, combined with management of stressful environmental conditions (lights, alarms, noise, etc.), and/or proximity and participation of the family (e.g. spending more time with the patient). In 9 (10.5%) of the units the presence of the family was encouraged over other non-pharmacological measures.

There was no protocol to promote rest and sleep for patients in 61 (70.9%) of the units, and one of the units with this protocol acknowledged that they did not apply it.

DiscussionThe representativeness of the ICU surveyed in the study is optimal, as shown by the confidence interval. The application of protocols to encourage early mobilisation, and the physiotherapy time available in the unit did not depend on whether or not it was in a university hospital, unlike the results of the recent international survey by Morandi et al. on the implementation of the ABCDEF bundle26 (A and B: awake and breathing, C: choice of analgesia and sedation; D delirium prevention; E: early mobilisation; F: family empowerment), which was used more in non-university hospitals.

Human resourcesIn relation to bedrest,8 the principal risk factor for developing ICUAW, the human resources for mobilising patients depended on the internal organisation of the department and the interprofessional team. According to Morandi,26 although only doctors were asked, no ICU in Spain had a ratio of 1:1, whereas 11% of international ICU had this ratio, and during the day the ratio 1:2 predominated, which increased considerably to 1:3 and 1:4 during the night. In Spain, the ratio only varied in 20% of the units, depending on the work shift or whether semi-critical patients were included, in the remainder it was a set ratio. This implies that balanced and dynamic management of workloads might encourage mobilisation, depending on how responsibilities are allocated. As the nurse: patient ratio increased less care was delivered to patients, in non-invasive mechanical ventilation,27 for example. This ratio has not been studied in clinical trials on early mobilisation, and depends on the professional in charge of leading mobilisation. In some studies, the physiotherapist assesses the patient and guides mobilisation according to their assessment but uses supplementary personnel (ancillary staff or nursing assistants) to carry out active exercises.28,29 In other studies, the physiotherapists mobilise the patient together with the nurse in charge of the patient, with no additional resources, because the physiotherapist and/or occupational therapist forms part of the unit's staff and work there full-time.21,30,31 The survey by Morandi26 asked whether the unit had a mobilisation team, and the doctors surveyed in Europe answered that 34% of units had this team. This team was defined in three different ways: physiotherapist, physiotherapist and nurses, physiotherapist together with respiratory physiotherapist and nurses. As highlighted by Garzón-Serrano et al.,32 physiotherapists achieve higher levels of mobilisation than nurses, who are more conservative with regard to patients’ functional abilities. This difference is due to the responsibilities inherent to each profession, since nurses assess the patient overall and are concerned by potential haemodynamic instability, whereas physiotherapists focus more on musculoskeletal assessment and contracture risk.

Clearly, as stated by McWilliams,28 Stiller33 and Hodgin,34 the functions and presence of the physiotherapist vary greatly according to the country. In Spain, 65.1% of units can use a physiotherapist by consulting with the rehabilitation doctor. This can delay the start of mobilisation, which is then no longer early, within the first 5 days following admission to ICU, and it is further delayed since 86% of the ICU surveyed did not implement a mobilisation protocol.

Blood glucose controlIn relation to hyperglycaemia, another ICUAW risk factor identified in various studies on early mobilisation,11,12 we highlight that it is clear that blood glucose control protocols are used more than mobilisation protocols, since almost 60% of the ICU with an appropriate blood glucose range according to the latest recommendations,35,36 between 110 and 180mg/dl, implement them. Various studies coincide in not recommending a tight blood glucose range, 80–110mg/dl,37 which was advocated earlier in the pioneering NICE-SUGAR study38 which failed to replicate the good results obtained by Van den Berghe39 in terms of infection reduction, transfusion requirements, kidney failure and polyneuropathy. This lack of reproducibility was put down to there being no standardisation in blood sugar measurement. Experts currently advise against using capillary blood to test blood glucose in critical patients because it overestimates blood glucose in most cases due to insufficient peripheral circulation related to the administration of vasopressors,22,40,41 as well as microhaematomas cased by repeated puncture of the distal phalanges, a further source of pain for critical patients. Even so, it is used in 86% of units in Spain, which is of concern because 93% of units test with bedside glucose metres, despite the current evidence that the glucose metres routinely used for testing blood glucose in outpatients are not reliable for detecting blood glucose in critical patients.42 These glucose metres are not reliable for anaemic patients, because they do not automatically correct haematocrit bias in measuring blood glucose, anaemia being common in these patients, with an incidence of 90% in patients with a stay of only 72h in ICU, increasing to 98% on the eighth day following admission.43 If we take into account the current recommendation not to transfuse until there are haemoglobin levels below 7g/dl,44 we can confirm that anaemia is highly associated with critical patients. StatStrip® (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA) is the only blood glucose monitor recognised by the FDA23 as suitable for assessing blood glucose levels in critical patients, and in our study only 3.5% of the ICI claimed to use it. The blood glucose monitors that use glucose dehydrogenase are a second option, Accu-Chek® (Roche) and Hemocue® (HemoCue Inc) because they interfere with fewer substances, and are already more frequently used, in 23.3% of the units.

Analgosedation controlWith regard to the protocols used in the ICU relating to mobilisation, the sedation protocol is essential because it determines the level of cooperation of the patient with the exercises. Moderate sedation is necessary, defined in the literature as an optimal RASS range of between −2 and 0.24 Therefore it follows that scales to monitor sedation levels should be used, which still do not exist in 12.8% of the units, and 11.6% use a scale that is not recommended, the Ramsay scale, which does not enable evaluation of anxiety-agitation levels, the other face of suboptimal sedation. Nevertheless our practice is better compared to the European average26 (RASS 65% vs. 48%, Ramsay 12% vs. 31%), and the Belgian average45 in particular, where use of the Ramsay scale was 64% in 2014.

Obviously, a protocol must regulate the frequency of assessment and consequently, the adjustment of analgesia and sedation doses, but 64% of ICU in Spain do not have a sedation protocol (51% in Europe,) and of the units that do use a protocol, only 15% use multidisciplinary protocols with algorithms, i.e., dynamic, and 11.6% use daily interruption of sedation, the latter percentage being a fourth of that of Europe.26 At present no practice has been demonstrated as better or used more than another24 but analysing the results of this study, where, with a clearly significant difference, nurses assess sedation, it is likely that a nurse-led protocol would be more dynamic than medically prescribed daily interruption of sedation. The study by Sneyers et al.45 undertaken in Belgium, used dynamic sedation protocols for 33% of patients compared, according to their study data, with the United Kingdom (80%), and the United States (71%). The authors of this study concluded that the use of scales is illogical if dynamic protocols are not used, because they increase the risk of delay to optimal treatment of sedation levels. Furthermore, if the sedation protocols do not empower nurses (greater autonomy to manage drugs according to the levels provided by the sedation scales) these scales will be used less over time. This is comparable to requesting blood glucose measurement hourly with no blood glucose protocol to regulate insulin doses.

In addition, dynamic protocols regulate the administration of analgesia, which is not always the case with daily interruption of sedation since, as shown in the Belgian study,45 only 42% of the professionals surveyed evaluated pain during the sedation window, and did so principally guided by changes in vital signs or behaviour. Only 11% of the units used a scale, a clearly higher percentage in our study, for both communicative and uncommunicative patients, although it should be improved principally for the latter, despite both being above the European average shown in the study by Morandi26 (74% vs. 58% and 47% vs. 10%, respectively).

Control of the risk of deliriumAs clearly stated by Latronico46 “persistent pain is a major problem for survivors of critical illness, and pain assessment in these patient was rated as “very important”. Experts in the rehabilitation of the critical patient agree,15 and more so since pain is a risk factor for the development of delirium,13,14 the other great enemy of mobilisation, in turn related to the types of sedation agents administered (the benzodiazepines are associated with a higher incidence of delirium compared to dexmedetomidine or propofol), and the type of analgesia (the higher the dose of opioids the greater the incidence of delirium compared to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or paracetamol), and the level of implementation of non-pharmacological measures (visible clock, natural light, hearing aids and glasses, presence of the family, earplugs and sleep mask to promote sleep).14,24

The RASS has shown good correlation with the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit, and therefore should serve as a guide to the patients to assess for potential delirium.24 It should be monitored once per shift and/or when there is a RASS + 1 to +4; this was only undertaken in one of the 86 units surveyed, others (31%) were guided by the presence of signs and symptoms of delirium, which is not specific because the vital signs do not determine differences between sedation levels,47 which may mask hypoactive delirium.

The lack of protocols for both the prevention and the management of delirium, around 70%, is similar to the European average,26 which does not encourage the use of validated scales to assess the presence of delirium, surprisingly underused in Spain compared to Europe (26% versus 90%) despite the same lack of protocols. In contrast, this lack does not affect the use of non-pharmacological measures (34% versus 20–30%), although according to the current evidence their effectiveness has not been demonstrated,14 they are basic for achieving sleep, and we should bear in mind that, despite finding no differences between the day and the night in terms of agitation episodes, Burk et al.48 found that the first episode usually occurs between 20h and 24h.

LimitationsWe could not contrast the responses by nurses compared to data collection on patients. In some cases we can confirm that a scale is assessed and not really applied in everyday practice. The role of the physiotherapist in ICU could have been examined in depth (time for each patient, tasks for which they are responsible) but the objective of the study was more to assess nursing care in relation to ICUAW. In order to avoid duplicating responses from the same unit, a likely situation when distributing online surveys and a cause of selection bias, we limited access to one nurse per unit using a password. This resulted in a lack of representativeness from some autonomous regions, where we could not contact interested investigators.

The clinical decisions and interventions to prevent ICUAW should be accompanied by the empowerment of nurses in the correct control of its associated risk factors, such as: blood glucose control, appropriate analgo-sedation doses, prevention and early treatment of delirium by implementing multidisciplinary protocols, that enable the inclusion of a physiotherapist in the team to direct the level of mobilisation according to the patient's functional abilities.

ConclusionsImplementation of the different protocols associated with the prevention of acquired muscle weakness was high in relation to the protocols for blood glucose control, assessment of sedation levels and pain of communicative patients, but low in terms of early mobilisation and delirium screening and prevention. Likewise, the presence of the physiotherapist in ICU is rare.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the Spanish Society of Intensive Care and Coronary Unit Nursing (SEEIUC) who promoted to the study internationally.

Coordinator Andalusia: María Esther Rodríguez Delgado. Authors: Antonia María Contreras Rodríguez; Ester Oreña Cimiano; Álvaro Ortega Guerrero; María del Carmen Martínez del Aguila; Virginia Rodríguez Monsalve; Carlos Leonardo Cano Herrera; Juan Manuel Masegosa Pérez, from the hospitals Poniente, Complejo hospitalario de especialidades Virgen de Valme, Quirón, Santa Ana.

Coordinator Aragon: Delia María González de la Cuesta. Autores: María Inmaculada Pardo Artero; Marta Palacios Laseca; Ana Isabel Cabello Casao; María Belén Vicente de Vera Bellostas; Carmen Pérez Martínez; Sheila Escuder González; Amelia Lezcano Cisneros; Antonio Miguel Romeo; Isabel López Alegre, from the hospitals Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa, Royo Villanova, University hospital Miguel Servet, Obispo Polanco of Teruel.

Coordinator Asturias: Emilia Romero de San Pío. Autores: Helena Fernández Alonso; Lara María Rodríguez Villanueva; Roberto Riaño Suárez, Begoña Sánchez Cerviñio, Sergio Carrasco Santos, from the Central university hospital of Asturias and University hospital of San Agustín.

Coordinator Canary Islands: Alicia San José Arribas. Autores: Miriam González García; Antonio Linares Tavio, from the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario of the Canary Islands.

Coordinator Cantabria: Paz Álvarez García. Autores: Nuria Polo Hernández; Lourdes Gómez Cosío; Isabel Pérez Loza; Ángela Suárez Pérez; Sonia Crespo Rebollo, from the Hospital Universitario Marqués of Valdecilla.

Coordinator Castilla La Mancha: Juan Carlos Muñoz Camargo. Autores: Julián García García; César Rojo Aguado; José Gómez López; Laura Sonseca Bartolomé, from the university hospitals of Guadalajara and Complejo Hospitalario Universitario of Albacete.

Coordinator Castilla y León: Alicia San José Arribas. Authors: Sonia del Olmo Nuñez; Patricia García Mazo; Eduardo Siguero Torres; Isabel Muñoz Díez, from the hospitals Río Ortega and Clínico Universitario of Valladolid.

Coordinator Catalonia: Pilar Delgado Hito. Authors: Mercedes Olalla Garrido Martín; Gemma Marín Vivó; María del Mar Eseverri Rovira; Montserrat Guillen Dobon; Montserrat Aran Esteve; Maribel Mirabete Rodríguez; Albert Mariné Méndez; Silvia Rodríguez Fernández; Joan Rosselló Sancho; Valeria Zafra Lamas; Inmaculada Carmona Delgado; Àngels Navarro Arilla; Gustau Zariquiey Esteva; Ángel Lucas Bueno Luna; Cristina Lerma Brianso; Rubén Gómez García; Bernat Planas Pascual; Marta Sabaté López; Ana Isabel Mayer Frutos; Roser Roca Escrihuela; Gemma Torrents Albà; Vanesa García Flores; Joan Melis Galmés; Sandra Belmonte Moral; Montserrat Grau Pellicer; Aintzane Ruiz Eizmendi; Carme Garriga Moll; Esteve Bosch de Jaureguízar, from the hospitals Universitari Vall d’Hebrón, Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Clínic de Barcelona, Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa, Universitari de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta, Universitari de Bellvitge.

Coordinator Extremadura: Sergio Cordovilla Guardia, Fidel López Espuela. Authors: Lara Mateos Hinojal; María Isabel Redondo Cantos from the Complejo Hospitalario of Cáceres.

Coordinator Galicia: María del Rosario Villar Redondo. Authors: Jesús Vila Rey, Susana Sánchez Méndez; Yolanda García Fernández; María Cristina Benítez Canosa; Mauricio Díaz Álvarez; José Ramón Cordo Isorna; Ángeles Estébez Penín; Gloria Güeto Rial; Esther Bouzas López, from the hospitals Universitario Lucus Augusti, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario of Ourense, Complexo Universitario Santiago of Compostela and Complexo Hospitalario Universitario of Santiago.

Coordinators Madrid: Susana Arias Rivera, María Jesús Frade Mera and María Jesús Luengo Alarcia. Authors: Noelia Regueiro Díaz; Luis Fernando Carrasco Rodríguez-Rey; María del Rosario Hernández García; Gema Sala Gómez; Javier Vecino Rubio; Saúl García González; María del Mar Sánchez Sánchez; Carmen Cruzado Franco; Beatriz Martín Rivera; Rocío González Blanco; Ana Belén Sánchez de la Ventana; María Luisa Bravo Arcas; Josefa Escobar Lavela; María del Pilar Domingo Moreno; Mercedes García Arias; Inmaculada Concepción Collado Saiz; María Acevedo Nuevo; Alejandro Barrios Suárez; Francisco Javier Zarza Bejarano; María Catalina Pérez Muñoz; Virginia Toribio Rubio; Patricia Martínez Chicharro; Alexandra Pascual Martínez; Sergio López Pozo; Laura Sánchez Infante; Verónica Ocaña García; Daniel Menes Medina; Ana Vadillo Cortázar; Gema Lendínez Burgos; Jesús Díaz Juntanez; María Teresa Godino Olivares; from the hospitals Universitario 12 de Octubre, Universitario of Móstoles, Universitario de Getafe, Universitario La Paz; Universitario Ramón y Cajal; Universitario Clínico San Carlos; Universitario del Sureste; Universitario Infanta Leonor, Universitario del Henares; Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda and General Universitario Gregorio Marañón.

Coordinator Murcia: Juan José Rodríguez Mondéjar. Authors: Francisco José Martínez Rojo; María Vanessa Ruiz Martínez; Daniel Linares Celdrán; Antonio Ros Molina; Javier Sáez Sánchez; José María Martínez Oliva; Ana Bernal Gilar; María Belén Hernández García; Antonio Tomás Ríos Cortés; Raquel Navarro Méndez; Sebastián Gil García; Juan Sánchez Garre, from the hospitals General Universitario J.M. Morales Meseguer, Universitario Los Arcos del Mar Menor, General Universitario Santa Lucía, Rafael Méndez, Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca and General Universitario Reina Sofía.

Coordinator Navarra: Miriam del Barrio Linares. Authors: Rosana Goñi Viguria and Raquel Aguirre Santano from the Clínica Universidad de Navarra.

Coordinator Basque Country: Maria Rosario García Díez. Authors: Laura Aparicio Cilla; Mónica Delicado Domingo; César Rodríguez Núñez; Ane Arrasate López, from the hospitals Universitario of Basurto and Universitario of Araba (headquarters Txagorritxu).

Coordinator Valencia: Ángela Romero Morán. Authors: Rosa Paños Melgoso; Mónica Yañez Cerón; Amparo Mercado Martínez; Beatriz Martínez Llopis; María Josefa Vayá Albelda; Javier Inat Carbonell; M. Rosario Alcayne Senent; Fátima Giménez García; Eva Cristina Fernández Gonzaga; Laura Febrer Puchol; Senén Berenguer Ortuño; María Pastor Martínez; Dunia Valera Talavera; María José Segrera Rovira; Yolanda Langa Revert; Maricruz Espí Pozuelo; María Ángeles de Diego Miravet; Beatriz Garijo Aspas; María del Rosario Asensio García; José Ramón Sánchez Muñoz; Quirico Martínez Sánchez; Ramón López Mateu from the hospitals Universitario Dr. Peset Aleixandre, General Universitario de Elda-Virgen de la Salud, Universitario of la Ribera, Luís Alcanyis de Xàtiva, Clínico Universitario of Valencia, Provincial of Castellón, General de Requena, Universitario San Juan of Alicante, Universitario of la Plana, Vega Baja of Orihuela and General Universitario of Elche.

More information about the authors of the MOviPre Group is available in Annex.

Please cite this article as: Raurell-Torredà M, Arias-Rivera S, Martí JD, Frade-Mera MJ, Zaragoza-García I, Gallart E, et al. Grado de implementación de las estrategias preventivas del síndrome post-UCI: estudio observacional multicéntrico en España. Enferm Intensiva. 2019;30:59–71.

This manuscript was awarded the IX San Juan de Dios Physiotherapy Research Paper Prize, Comillas Pontifical University, Madrid.