To describe and characterise the use of mechanical restraint (MR) in critical care units (CCU) in terms of frequency and quality of application and to study its relationship with pain/agitation-sedation/delirium, nurse:patient ratio and institutional involvement.

MethodMulticentre observational study conducted in 17 CCUs between February and May 2016. The observation time per CCU was 96 h. The main variables were the prevalence of restraint, the degree of adherence to MR recommendations, pain/agitation-sedation/delirium monitoring and institutional involvement (protocols and training of professionals).

ResultsA total of 1070 patients were included. The overall prevalence of restraint was 19.11%, in patients with endotracheal tube (ETT) 42.10% and in patients without ETT or artificial airway it was 13.92%. Adherence rates between 0% and 40% were obtained for recommendations related to non-pharmacological management and between 0% and 100% for those related to monitoring of ethical-legal aspects. The lower prevalence of restraint was correlated with adequate pain monitoring in non-communicative patients (P < .001) and with the provision of training for professionals (P = .020). An inverse correlation was found between the quality of the use of MR and its prevalence, both in the general group of patients admitted to CCU (r = −.431) and in the subgroup of patients with ETT (r = −.521).

ConclusionsRestraint is especially frequently used in patients with ETT/artificial airway, but is also used in other patients who may not meet the use profile. There is wide room for improvement in non-pharmacological alternatives to the use of MC, ethical and legal vigilance, and institutional involvement. Better interpretation of patient behaviour with validated tools may help limit use of MR.

Describir y caracterizar el uso de contenciones mecánicas (CM) en unidades de cuidados críticos (UCC) en términos de frecuencia y calidad de aplicación y analizar su relación con la monitorización del dolor/agitación-sedación/delirio, la ratio enfermera:paciente y la implicación institucional.

MétodoEstudio observacional multicéntrico realizado en 17 UCC entre febrero y mayo del año 2016. El tiempo de observación por UCC fue de 96 h. Las principales variables fueron la prevalencia de contenciones, el grado de adherencia a las recomendaciones de uso de CM, la monitorización del dolor/agitación-sedación/delirio y la implicación institucional (protocolos y formación de los profesionales).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 1.070 pacientes. La prevalencia general de contenciones fue del 19,11%, en pacientes con tubo endotraqueal (TET) del 42,10% y en pacientes sin TET ni vía aérea artificial del 13,92%. Se obtuvieron valores de adherencia entre el 0 y el 40% para las recomendaciones relacionadas con manejo no farmacológico y entre el 0 y el 100% para las relacionadas con la vigilancia de aspectos ético-legales. La menor prevalencia de contenciones se correlacionó con una adecuada monitorización del dolor en pacientes no comunicativos (p < 0,001) y con la impartición de formación a los profesionales (p = 0,020). Se halló correlación inversa entre la calidad de aplicación de CM y su prevalencia, tanto en el grupo general de pacientes ingresados en las UCC (r = −0,431) como en el subgrupo de pacientes con TET (r = −0,521).

ConclusionesLas contenciones son especialmente frecuentes en pacientes con TET/vía aérea artificial, pero también están presentes en otros pacientes que a priori no responden al perfil de uso atribuido. Las alternativas no farmacológicas al uso de CM, la vigilancia de aspectos éticos y legales y la implicación institucional presentan un amplio margen de mejora. La optimización de la interpretación del comportamiento del paciente con herramientas validadas puede constituir un elemento limitador del uso de CM.

What is known?

Internationally, use of restraints is seen as being a last resort (never a routine practice) to be applied only after all possible alternatives have been ruled out. Nonetheless, use of physical restraints (PR) in critical patients is highly prevalent, indeed being especially significant in patients with endotracheal intubation. Adherence to guidelines for PR use is conditional on non-routine, proportional, individualised use, in which ethical-legal aspects (medical prescription and use of standardised devices) are monitored, and expected and adverse effects are followed up.

What does this study contribute?

While restraints are particularly frequent in patients with endotracheal intubation or artificial airways, they are also present in other patients (subgroup of patients who, a priori, do not respond to the attributed profile of PR use).

Purpose-trained, systematic use of validated instruments for assessment of presence of pain in non-communicative patients can contribute to adopting a focused approach to comfort-wellbeing and guiding judicious PR use. These are elements which could serve to minimise PR use, improve institutional involvement through the adoption of concrete stances, ensure surveillance of ethical-legal aspects of PR use, and enhance measures for psycho-emotional and environmental restraint.

Implications of the study

Having a model with quality standards for PR application could serve to guide reflexive, reasoned and individualised use, monitor healthcare quality, and conduct comparative studies between units.

The use of physical restraints (PR) has been and continues to be a standard practice in intensive care units (ICU) in many countries1–3. That said, however, studies published to date, generally of an analytical and descriptive nature, provide limited information on this reality and the factors linked to their use4,5. PR use has mainly been justified as a measure to prevent patients from removing life-sustaining devices, such as endotracheal tubes (ETT), and one necessitated by low nurse:patient ratios1,3,5–8. Currently, social changes, in tandem with ethical problems posed by PR use and trends in generally accepted medical practice (lex artis), have led to these types of measures being questioned4,9,10. Hence, initiatives intended to promote a reasoned use of PR, with the aim of ultimately reducing their application, have been functioning satisfactorily for years in settings such as geriatrics and mental health11–14. Similarly, in the critical patient setting, papers are beginning to appear which reflect an interest in reviewing this practice, highlighting the lack of uniformity in PR use and frequency, and questioning its effectiveness2–4,15.

This interest in the appropriateness of indication of this procedure and the conditions of practice surrounding it has led to a framework of guidelines being generated, which advocate that PR be used as a last resort and exceptional measure, and propose a set of quality standards5,9,16–19.

Some results extracted from qualitative, observational studies and expert opinions suggest that management of analgesics and sedatives, interpretation of patient behaviour by means of systematically used validated scales, or PR management training in the case of critical patients, among others, could be modulating factors of PR use in ICU4,6,20–24.

Likewise, the increasingly dubious effectiveness of PR in terms of preventing self-removal of life-sustaining devices4,5,15 and the confrontation with current models such as eCash (early Comfort using Analgesia, minimal Sedatives and maximal Humane care) proposed by Vincent et al10 or the ABCDEF Bundle (Assess, prevent, and manage pain; Both spontaneous awakening trials and spontaneous breathing trials; Choice of sedation and analgesia; Delirium assessment, prevention, and management; Early mobility and exercise; and Family communication and involvement) developed by W. Ely’s group20,25, render a review of PR use a relevant matter that calls for new studies and evidence4,5.

This study had a twofold aim: primarily, to describe and characterise PR use in ICU in the Madrid Region in terms of the frequency and quality of its application, by reference to compliance with a set of standards drawn from the literature; and at a secondary level, to analyse the relationship between PR use, pain/agitation-sedation/delirium (PAD) monitoring, nurse: patient ratios, and institutional involvement (existence of protocols and training of health professionals) in the application of such measures.

MethodsStudy design and scopeMulticentre observational study conducted at a total of 17 ICU belonging to 11, level-2 and level-3 public university teaching hospitals in the same region, from February to May 2016.

Participants and samplingWe included polyvalent, medical and surgical ICU. Purposive convenience sampling was performed at 21 ICU in the Madrid Region proposed to form part of the study. Finally, 17 units agreed to participate. At the participating ICU, we included all patients aged 18 years or over admitted across the study period.

A patient with PR was defined for study purposes as any patient to whom a device had been applied at some point in time to immobilise him/her or reduce his/her ability to move freely (wrist bands, mittens, etc.)4,26. Bed-side rails were excluded as PR, given the different intent behind their application to critical patients1,4,27,28.

Data-collectionObservation was conducted for a total of 96 h at each ICU, with this period being divided into four monthly sub-periods (February-March-April-May) of 24 h each, in order to enhance the representativeness of the sample.

The research collaborator at each ICU recorded the data by direct observation, review of clinical histories (CRs), and interviews with the professionals involved in the care of each patient. All researchers were required to undergo prior training and the Case Report Form was pilot-tested.

Variables recordedVariables related with each of the following aspects were recorded:

General descriptive elements of each ICUNote was taken of the following: number of patients admitted; number of patients with PR; number of patients fitted with artificial airways (AAs) (ETT, tracheostomy cannula); number of patients with non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV); number of self-removed devices; and type of device. For each ICU, we recorded the nurse:patient ratio, and the existence of specific written PR protocol and/or specific training of professionals in PR management of critical patients (accepting the different periods of in-house training given by the units or services concerned as valid).

Data relating to institutional PAD monitoring policiesFor each ICU we recorded: compliance/non-compliance with appropriate PAD monitoring5,29, where applicable; pain monitoring (a) in communicative patients, institutional regulation requiring a record to be kept of the Numerical Verbal Scale (NVS) or Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score, at least once every nursing shift, or (b) in non-communicative patients, institutional regulation requiring a record to be kept of the Behavioural Pain Indicator Scale (ESCID), Behavioural Pain Scale (BPS) or Critical Care Observation Tool (CPOT) at least once every nursing shift; (c) institutional regulation requiring a record to be kept of appropriate sedation by means of the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) or Sedation Agitation Scale (SAS) and/or use of objective systems such as Bispectral Index® (BIS®), as the case may be, at least once every nursing shift; and institutional regulation requiring a record to be kept of systematic delirium screening with the Confusion Assessment Method for diagnosing delirium in ICU (CAM-ICU) or Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC), at least once every 24 h.

Elements linked to PR-application qualityIn patients with restraints the following were recorded: concomitant use of PR and analgesia/sedation/neuromuscular blocking agents; location; whether the material applied was certified; time and indication of use; record of prescription in patient’s CR; existence of a signed consent form, if alternative approaches had been tried prior to application; and adverse physical or behavioural effects related to PR placement1,4,5,8.

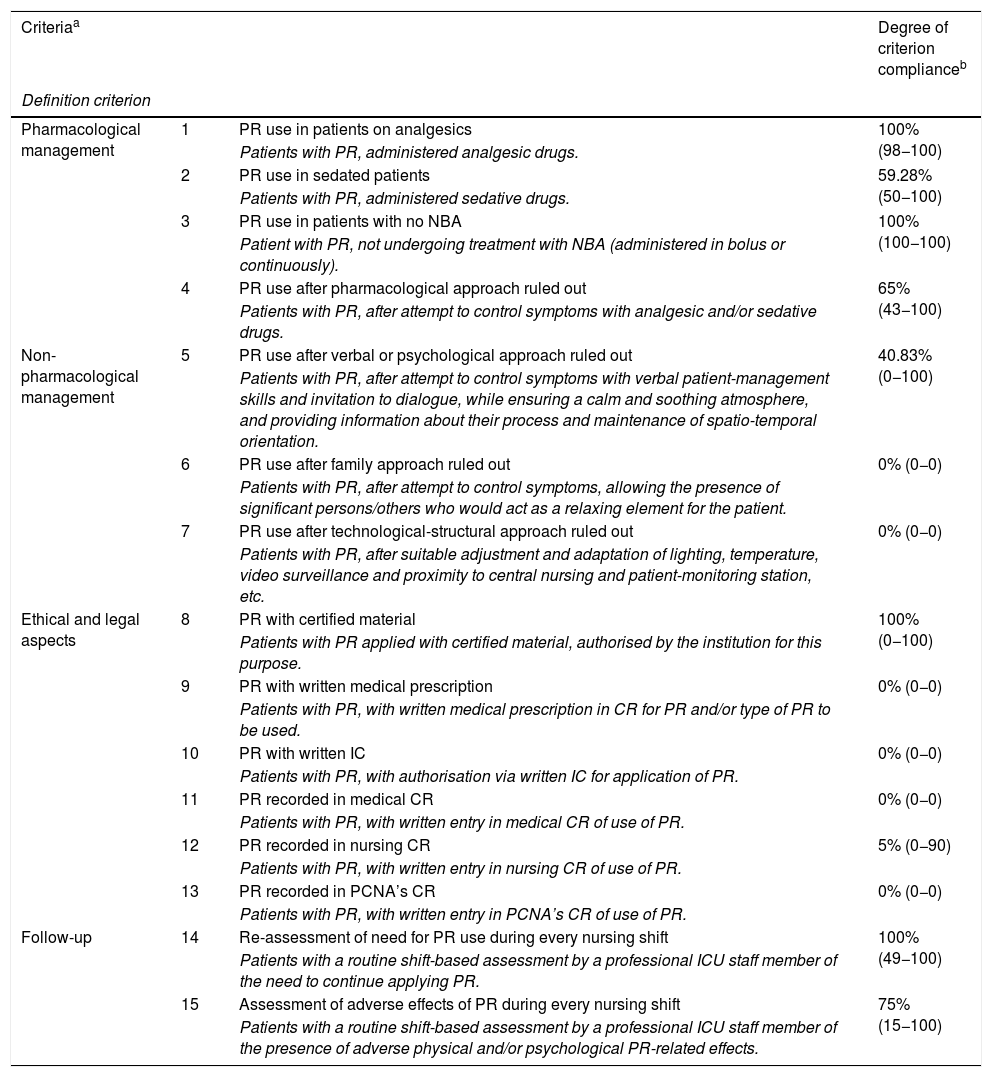

Based on these variables, a new variable was created, entitled “Degree of adherence to guidelines for PR use” (Adherence to guidelines), which sought to audit PR application quality and was defined by a set of 15 criteria9,19, each with a goal of 100% compliance (Table 1). The variable “Adherence to guidelines” was created ad hoc on the basis of the literature review, the prevailing regulatory framework, and the authors’ knowledge of the issue. It was envisaged as a guide to allow for assessment of adherence to the criteria/guidelines governing PR use, understood as a process of continuous improvement until achievement of 100% compliance, with no criterion of grading or scaling thus being established.

“Degree of adherence to guidelines for PR use” – criteria and degree of compliance.

| Criteriaa | Degree of criterion complianceb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition criterion | |||

| Pharmacological management | 1 | PR use in patients on analgesics | 100% (98−100) |

| Patients with PR, administered analgesic drugs. | |||

| 2 | PR use in sedated patients | 59.28% (50−100) | |

| Patients with PR, administered sedative drugs. | |||

| 3 | PR use in patients with no NBA | 100% (100−100) | |

| Patient with PR, not undergoing treatment with NBA (administered in bolus or continuously). | |||

| 4 | PR use after pharmacological approach ruled out | 65% (43−100) | |

| Patients with PR, after attempt to control symptoms with analgesic and/or sedative drugs. | |||

| Non-pharmacological management | 5 | PR use after verbal or psychological approach ruled out | 40.83% (0−100) |

| Patients with PR, after attempt to control symptoms with verbal patient-management skills and invitation to dialogue, while ensuring a calm and soothing atmosphere, and providing information about their process and maintenance of spatio-temporal orientation. | |||

| 6 | PR use after family approach ruled out | 0% (0−0) | |

| Patients with PR, after attempt to control symptoms, allowing the presence of significant persons/others who would act as a relaxing element for the patient. | |||

| 7 | PR use after technological-structural approach ruled out | 0% (0−0) | |

| Patients with PR, after suitable adjustment and adaptation of lighting, temperature, video surveillance and proximity to central nursing and patient-monitoring station, etc. | |||

| Ethical and legal aspects | 8 | PR with certified material | 100% (0−100) |

| Patients with PR applied with certified material, authorised by the institution for this purpose. | |||

| 9 | PR with written medical prescription | 0% (0−0) | |

| Patients with PR, with written medical prescription in CR for PR and/or type of PR to be used. | |||

| 10 | PR with written IC | 0% (0−0) | |

| Patients with PR, with authorisation via written IC for application of PR. | |||

| 11 | PR recorded in medical CR | 0% (0−0) | |

| Patients with PR, with written entry in medical CR of use of PR. | |||

| 12 | PR recorded in nursing CR | 5% (0−90) | |

| Patients with PR, with written entry in nursing CR of use of PR. | |||

| 13 | PR recorded in PCNA’s CR | 0% (0−0) | |

| Patients with PR, with written entry in PCNA’s CR of use of PR. | |||

| Follow-up | 14 | Re-assessment of need for PR use during every nursing shift | 100% (49−100) |

| Patients with a routine shift-based assessment by a professional ICU staff member of the need to continue applying PR. | |||

| 15 | Assessment of adverse effects of PR during every nursing shift | 75% (15−100) | |

| Patients with a routine shift-based assessment by a professional ICU staff member of the presence of adverse physical and/or psychological PR-related effects. | |||

PR: physical restraints; NBA: neuromuscular blocking agents; CR: clinical record; PCNA: patient care nursing assistant; IC: informed consent.

In addition to recording PR prevalence in the total sample, PR prevalence was also calculated in patients with AAs or VMNI. For calculation purposes, the measurement was made for a specific period (24-h interval), with subsequent pooling of results (aggregate median of the 4 observations).

Furthermore, we created a new variable, “Compliance with the standard of PR use”, in relation to which the ICU were stratified into compliers/ non-compliers with the standard. The compliance cut point was set at a use prevalence of 15% or under, the lowest figure published for critical patients in Spain30 and an initially desirable goal for all comparable ICU.

Data-analysisWe performed the following: a descriptive analysis of categorical variables using absolute and relative frequencies; and a descriptive analysis of numerical variables using mean and standard deviation, or the median and 25th (P25) and 75th percentiles (P75), according to compliance with the normality assumption.

For analysis purposes, “Adherence to guidelines” was calculated as the median percentage of compliance with the 15 criteria at each ICU, and with each of the criteria at all the ICU as a whole.

The relationship between the variables and PR-application quality, measured as “Adherence to guidelines”, and the quantity of PR, measured as “Compliance with the standard of PR use“, was analysed using the U Mann-Whitney test for numerical variables and the Chi-squared or Fisher exact test statistic for categorical variables. The numerical variables were compared using the Pearson/Spearman correlation analysis. The level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

In view of the fact that the data were collected in four observation sub-periods, for analysis purposes we used measurements for the overall period (data pooled for the 96 h of observation at each ICU), or measurements for a specific period (24 h) with subsequent pooling of the results.

The statistical software package used was Stata/IC v.15.1.

Ethical approval and quality criteriaThe study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees (CRECs) of the respective hospitals, with the CREC of the Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda University Teaching Hospital acting as the reference committee (Meeting Minutes Nos. 306 and 308). Approval was likewise obtained from the respective Heads of Department and Nursing Supervisors of the units involved.

Once the researchers were purpose-trained, the case-report form was pilot-tested, and the data were collected simultaneously at all the ICU and then analysed on an aggregate basis, with hospitals, units, patients and professional participants being anonymised for the purpose.

After express consent had been obtained from the CRECs of the respective hospitals involved, individual consent was not sought, in view of the fact that the proposal had the nature of an audit. Hence, the data recorded are aggregate data and the Case Report Forms were distributed and collected, guaranteeing anonymity.

ResultsThe study covered a total of 17 ICU and 1070 patients, 366 of whom (34.20%) had ETT.

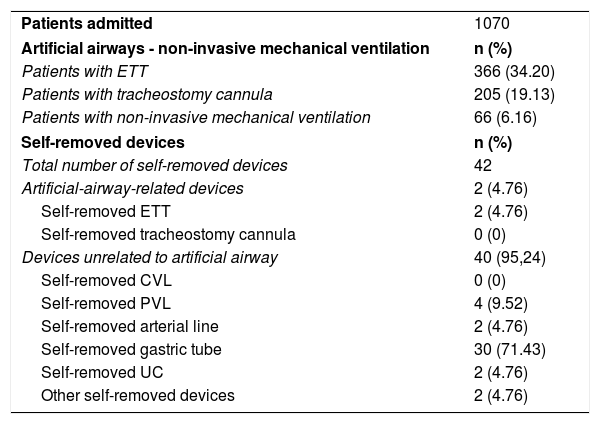

A description of the general characteristics of the sample and patients with PR can be seen in Tables 2–4.

General characteristics of the sample – intensive care units.

| Number of ICU | 17 |

| Monitoring of pain-agitation-delirium, n (%) | |

| Appropriate monitoring pain_communicative | 11 (64.71) |

| Appropriate monitoring pain_non-communicative | 6 (35.29) |

| Appropriate monitoring of sedation | 15 (88.24) |

| Appropriate monitoring of delirium | 2 (11.76) |

| Institutional variables | |

| Specific PR protocol for ICU | 7 (41.18) |

| Specific PR training in ICU | 2 (11.76) |

| Nurse:patient ratio (mean) | 1:2 |

ICU: intensive care units; PR: physical restraints.

General characteristics of patients observed.

| Patients admitted | 1070 |

| Artificial airways - non-invasive mechanical ventilation | n (%) |

| Patients with ETT | 366 (34.20) |

| Patients with tracheostomy cannula | 205 (19.13) |

| Patients with non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 66 (6.16) |

| Self-removed devices | n (%) |

| Total number of self-removed devices | 42 |

| Artificial-airway-related devices | 2 (4.76) |

| Self-removed ETT | 2 (4.76) |

| Self-removed tracheostomy cannula | 0 (0) |

| Devices unrelated to artificial airway | 40 (95,24) |

| Self-removed CVL | 0 (0) |

| Self-removed PVL | 4 (9.52) |

| Self-removed arterial line | 2 (4.76) |

| Self-removed gastric tube | 30 (71.43) |

| Self-removed UC | 2 (4.76) |

| Other self-removed devices | 2 (4.76) |

ETT: endotracheal tube; CVL: central venous line; PVL: peripheral venous line; UC: urinary catheter.

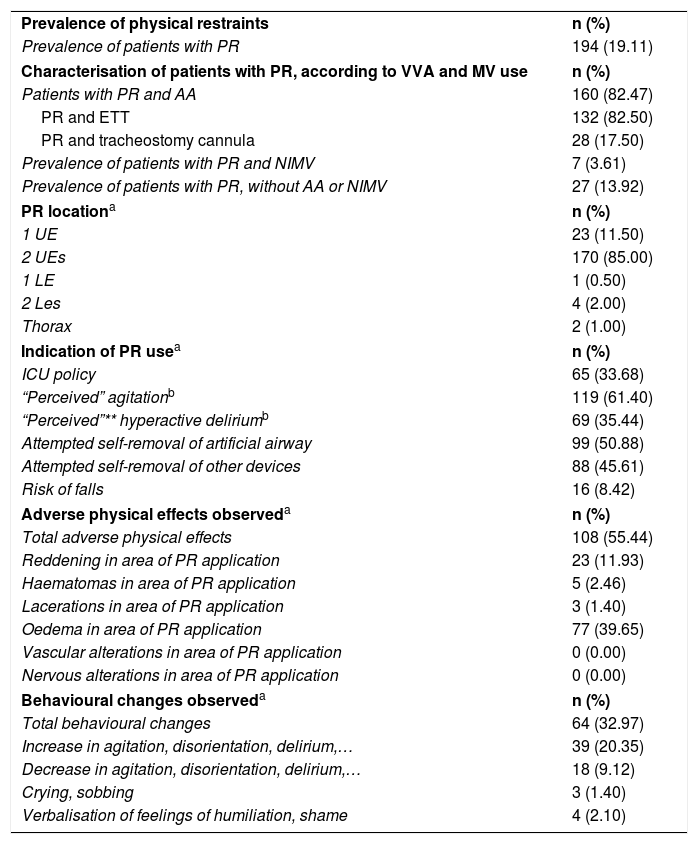

Characteristics of patients with physical restraints.

| Prevalence of physical restraints | n (%) |

| Prevalence of patients with PR | 194 (19.11) |

| Characterisation of patients with PR, according to VVA and MV use | n (%) |

| Patients with PR and AA | 160 (82.47) |

| PR and ETT | 132 (82.50) |

| PR and tracheostomy cannula | 28 (17.50) |

| Prevalence of patients with PR and NIMV | 7 (3.61) |

| Prevalence of patients with PR, without AA or NIMV | 27 (13.92) |

| PR locationa | n (%) |

| 1 UE | 23 (11.50) |

| 2 UEs | 170 (85.00) |

| 1 LE | 1 (0.50) |

| 2 Les | 4 (2.00) |

| Thorax | 2 (1.00) |

| Indication of PR usea | n (%) |

| ICU policy | 65 (33.68) |

| “Perceived” agitationb | 119 (61.40) |

| “Perceived”** hyperactive deliriumb | 69 (35.44) |

| Attempted self-removal of artificial airway | 99 (50.88) |

| Attempted self-removal of other devices | 88 (45.61) |

| Risk of falls | 16 (8.42) |

| Adverse physical effects observeda | n (%) |

| Total adverse physical effects | 108 (55.44) |

| Reddening in area of PR application | 23 (11.93) |

| Haematomas in area of PR application | 5 (2.46) |

| Lacerations in area of PR application | 3 (1.40) |

| Oedema in area of PR application | 77 (39.65) |

| Vascular alterations in area of PR application | 0 (0.00) |

| Nervous alterations in area of PR application | 0 (0.00) |

| Behavioural changes observeda | n (%) |

| Total behavioural changes | 64 (32.97) |

| Increase in agitation, disorientation, delirium,… | 39 (20.35) |

| Decrease in agitation, disorientation, delirium,… | 18 (9.12) |

| Crying, sobbing | 3 (1.40) |

| Verbalisation of feelings of humiliation, shame | 4 (2.10) |

ICU: intensive care units; PR: physical restraints; ETT: endotracheal tube; AA: artificial airway; MV: mechanical ventilation; NIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; UE: upper extremity; LE: lower extremity.

Of the total number of patients, 194 had some type of restraint, amounting to a median prevalence of PR use of 19.11% (P25:9.9-P75:25.75) (Table 5), with wide variability in both the overall group of patients and those with ETT (Table 5).

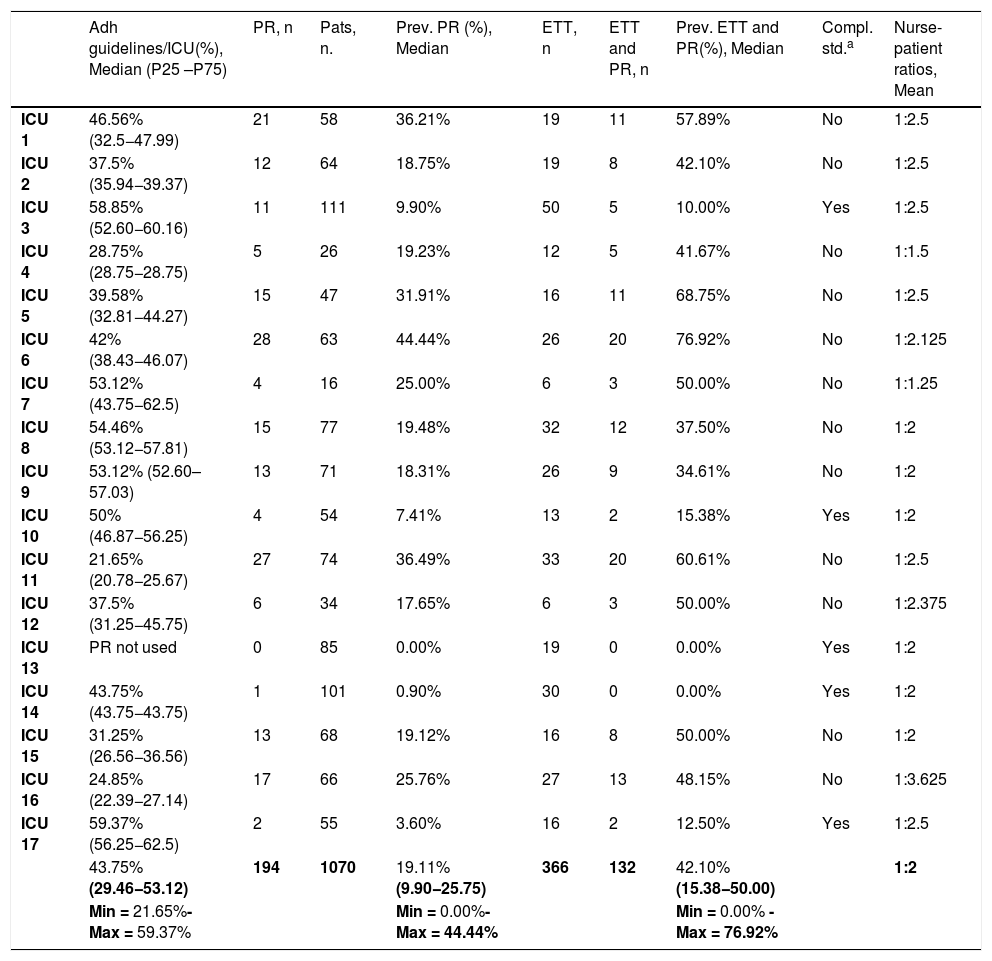

Characterisation of intensive care units according to degree of adherence to guidelines for PR use, prevalence of physical restraints, prevalence of physical restraints in intubated patients, compliance with standard of prevalence of restraints, and nurse:patient ratios.

| Adh guidelines/ICU(%), Median (P25 –P75) | PR, n | Pats, n. | Prev. PR (%), Median | ETT, n | ETT and PR, n | Prev. ETT and PR(%), Median | Compl. std.a | Nurse-patient ratios, Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU 1 | 46.56% (32.5−47.99) | 21 | 58 | 36.21% | 19 | 11 | 57.89% | No | 1:2.5 |

| ICU 2 | 37.5% (35.94−39.37) | 12 | 64 | 18.75% | 19 | 8 | 42.10% | No | 1:2.5 |

| ICU 3 | 58.85% (52.60−60.16) | 11 | 111 | 9.90% | 50 | 5 | 10.00% | Yes | 1:2.5 |

| ICU 4 | 28.75% (28.75−28.75) | 5 | 26 | 19.23% | 12 | 5 | 41.67% | No | 1:1.5 |

| ICU 5 | 39.58% (32.81−44.27) | 15 | 47 | 31.91% | 16 | 11 | 68.75% | No | 1:2.5 |

| ICU 6 | 42% (38.43−46.07) | 28 | 63 | 44.44% | 26 | 20 | 76.92% | No | 1:2.125 |

| ICU 7 | 53.12% (43.75−62.5) | 4 | 16 | 25.00% | 6 | 3 | 50.00% | No | 1:1.25 |

| ICU 8 | 54.46% (53.12−57.81) | 15 | 77 | 19.48% | 32 | 12 | 37.50% | No | 1:2 |

| ICU 9 | 53.12% (52.60–57.03) | 13 | 71 | 18.31% | 26 | 9 | 34.61% | No | 1:2 |

| ICU 10 | 50% (46.87−56.25) | 4 | 54 | 7.41% | 13 | 2 | 15.38% | Yes | 1:2 |

| ICU 11 | 21.65% (20.78−25.67) | 27 | 74 | 36.49% | 33 | 20 | 60.61% | No | 1:2.5 |

| ICU 12 | 37.5% (31.25−45.75) | 6 | 34 | 17.65% | 6 | 3 | 50.00% | No | 1:2.375 |

| ICU 13 | PR not used | 0 | 85 | 0.00% | 19 | 0 | 0.00% | Yes | 1:2 |

| ICU 14 | 43.75% (43.75−43.75) | 1 | 101 | 0.90% | 30 | 0 | 0.00% | Yes | 1:2 |

| ICU 15 | 31.25% (26.56−36.56) | 13 | 68 | 19.12% | 16 | 8 | 50.00% | No | 1:2 |

| ICU 16 | 24.85% (22.39−27.14) | 17 | 66 | 25.76% | 27 | 13 | 48.15% | No | 1:3.625 |

| ICU 17 | 59.37% (56.25−62.5) | 2 | 55 | 3.60% | 16 | 2 | 12.50% | Yes | 1:2.5 |

| 43.75% (29.46−53.12) | 194 | 1070 | 19.11% (9.90−25.75) | 366 | 132 | 42.10% (15.38−50.00) | 1:2 | ||

| Min = 21.65%-Max = 59.37% | Min = 0.00%-Max = 44.44% | Min = 0.00% - Max = 76.92% |

ICU: intensive care units; Adh guidelines: Degree of adherence to guidelines for PR use; n: number; PR: physical restraints; pats.: patients; prev.: prevalence; ETT: endotracheal tube; Compl. std.: compliance standard.

The application profile corresponded mainly to patients with AAs (82.47%) and ETT (68.01%), with the most frequent indications of use being agitation (61.40%) and attempted self-removal of AA (50.88%). The most common PR location was on both UEs (85%). The most frequent adverse effects were oedema in the area of application (39.65%), and heightened agitation, disorientation and delirium (20.35%).

In 33.68% of cases, PR were applied as a matter of ICU policy, i.e., without a reasoned assessment of the need for such use in each particular case.

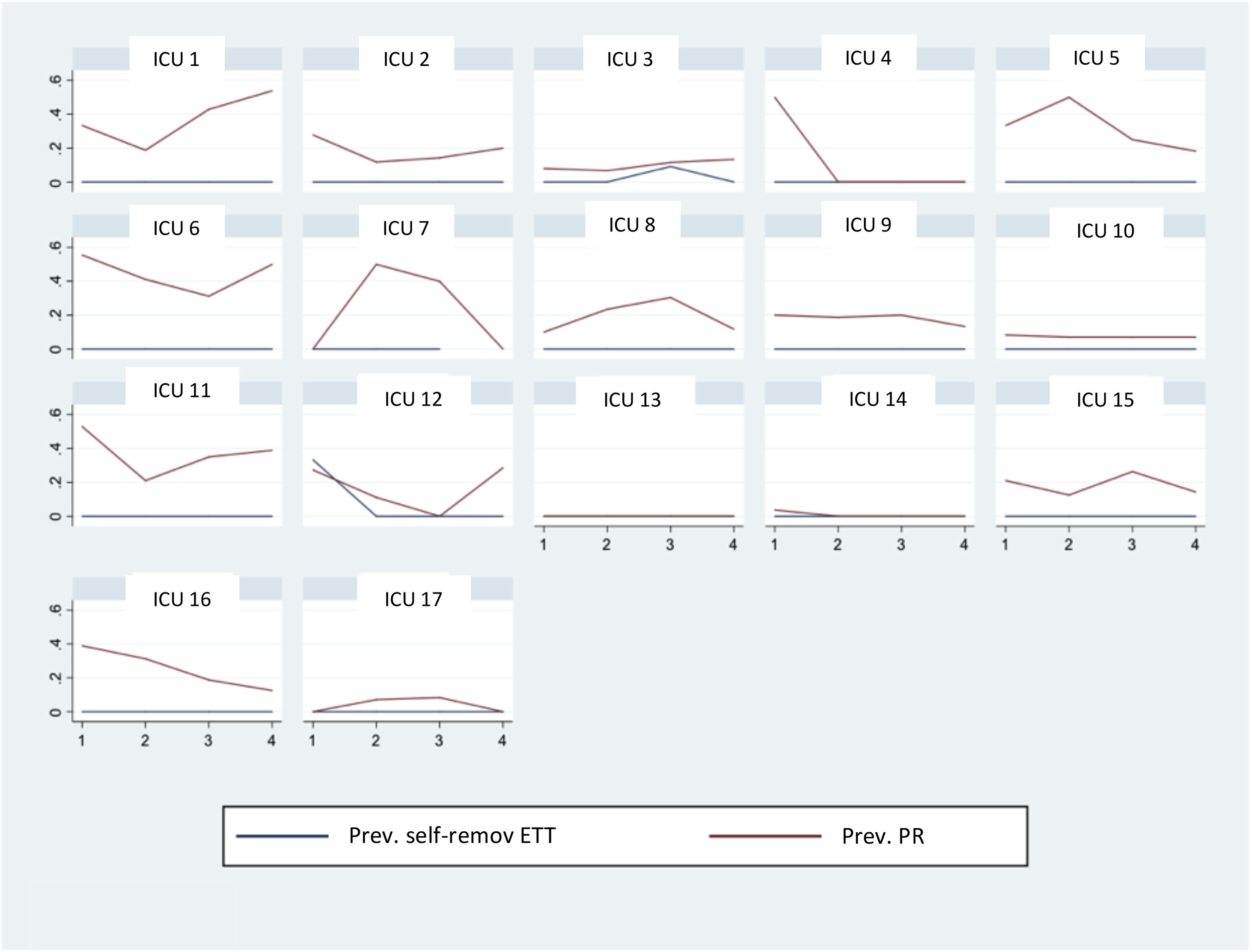

Although the number of ETT self-removals was small, the relationship between frequency of PR and ETT self-removal was nonetheless examined by plotting a graph depicting the parallel trends in the number of PR on the one hand and the number of ETT self-removals on the other. To this end, each ICU’s total observation period of 96 h was divided into four sub-periods of 24 h, and in each of these sub-periods the partial prevalences of PR and ETT self-removals were recorded. As can be seen in Fig. 1, there was no pattern to show that the decrease in PR use might correspond to the increase in ETT self-removals. At some ICU, however, a reduction in PR use was observed as the respective observation periods progressed.

Degree of adherence to guidelines for physical restraint useAnalysis of compliance with the set of criteria (“Adherence to guidelines”) at each ICU (Table 5) showed widely dispersed values, ranging from 21.65% to 58.75%, with a median approximation of 43.75% (value far below the ideal standard of 100% compliance).

For all the ICU as whole (Table 1), compliance closer to the ideal of 100% was seen in respect of criteria relating to pharmacological management (60-100%). This was in direct contrast to approaches linked to non-pharmacological aspects, where were no reports of the possibility of family or technological-structural approaches being considered prior to PR application. Requests for consent or some clinical record of the measure were practically non-existent. There were important differences among the ICU in terms of follow-up of restraint application.

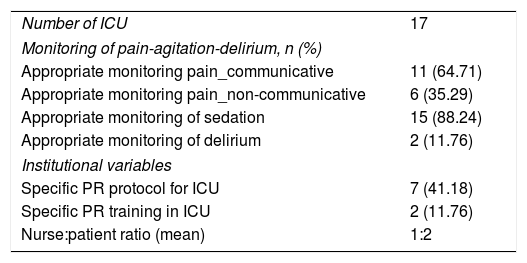

Monitoring of pain/agitation/delirium and institutional variables and use of physical restraintsA total of 64.71% of ICU performed appropriate pain monitoring in communicative patients versus 35.29% in non-communicative patients; in 88.24% of ICU in the case of sedation; and 11.76% of ICU in the case of delirium. 41.18% of ICU had a specific PR management protocol, with specific training having been imparted in 2. The mean nurse:patient ratio was 1:2 (range 1:1.25 to 1:3.62) (Tables 2 and 5).

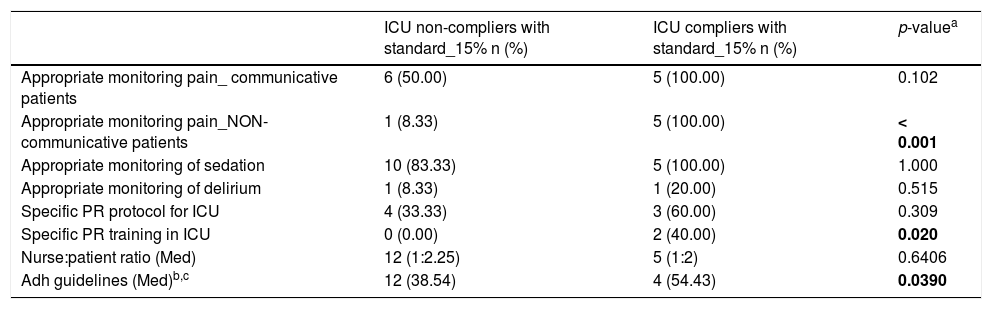

The ICU were classified by reference to prevalence of PR use, as compliers/non-compliers with the standard (prevalence of less than 15%). Of the 17 ICU, five (29.41%) complied with the standard (Table 5). An analysis of the relationship between compliance with the standard on the one hand, and PAD monitoring variables, use of protocols and training of health professionals on the other (Table 6). Lower prevalence of PR use was associated with appropriate pain monitoring in non-communicative patients (p < 0.001) and with health professional training in PR management at ICU (p = 0.020) (Table 6). With regard to correlation with monitoring of delirium, no conclusions can be drawn due to the scant number of ICU that monitored delirium appropriately.

Variables associated with compliance/non-compliance with standard of prevalence (15%).

| ICU non-compliers with standard_15% n (%) | ICU compliers with standard_15% n (%) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate monitoring pain_ communicative patients | 6 (50.00) | 5 (100.00) | 0.102 |

| Appropriate monitoring pain_NON-communicative patients | 1 (8.33) | 5 (100.00) | < 0.001 |

| Appropriate monitoring of sedation | 10 (83.33) | 5 (100.00) | 1.000 |

| Appropriate monitoring of delirium | 1 (8.33) | 1 (20.00) | 0.515 |

| Specific PR protocol for ICU | 4 (33.33) | 3 (60.00) | 0.309 |

| Specific PR training in ICU | 0 (0.00) | 2 (40.00) | 0.020 |

| Nurse:patient ratio (Med) | 12 (1:2.25) | 5 (1:2) | 0.6406 |

| Adh guidelines (Med)b,c | 12 (38.54) | 4 (54.43) | 0.0390 |

ICU: intensive care units; PR: physical restraints; Med: median; Adh guidelines: Degree of adherence to guidelines for PR use.

Lastly, an analysis was conducted to ascertain the possible relationship between Optimal PR use in accordance with percentage compliance with the criteria considered and institutional strategies (use of protocols or educational interventions), PR prevalence and nurse:patient ratios. The analysis was performed on a total sample of 16 ICU, since “Adherence to guidelines” could not be calculated for one of the ICU, owing to the fact that no restraints were applied during the observation period.

The first of the institutional strategies analysed was implementation of the ICU-specific PR protocol: six of the 16 units had implemented it, and in this group median “Adherence to guidelines” was 46.87%; the remaining 10 ICU, with no specific protocol, registered a median “Adherence to guidelines” of 39.75%. Hence, no statistically significant relationship was found between existence of an implemented protocol and “Adherence to guidelines” (p = 0.3165). The other institutional strategy analysed was specific training for PR use in critical patients: in this case, only one of the ICU had received training and therefore had a median “Adherence to guidelines” (43.75%); in the remaining 15 units, median Optimal Use was 42.01%,

No correlation was found between “Adherence to guidelines” and the nurse:patient ratio (r = −0.235, p = 0.3820). Yet, there was an inverse correlation with PR prevalence and with PR prevalence in patients with ETT of r = −0.431 and −0.521 respectively, with a p-value in both cases <0.001; in other words, those ICU which registered better use of restraints in terms of quality displayed a lower prevalence of PR use, both in the overall group of patients and in the subgroup of patients with ETT.

DiscussionIn the ICU included in our study, median prevalence of PR use was 19.11% and ranged from 0% to 44.44%, figures that doubled among patients with ETT. These data lie within the range of use observed by other studies. While publications from the United Kingdom (UK) and Scandinavian countries report prevalences of close on 0%, this figure stands at 76% in Canada, 39% in the USA, 43% in Italy, around 23% in Holland, and 15.6% to 43.9% in Spain1–3,23,30–33. The same occurs with PR use in patients with ETT. Our data show a prevalence of 42.10% in patients with ETT, yet studies undertaken in France, Japan, Jordan and Canada report prevalences of as high as 76.9%2,8,33–35. Comparison of these data reflects great differences in percentage use, which might be accounted for by cultural and routine-related differences in PR use at the respective ICU, as well as differences in admission criteria and intubated-patient management protocols36–42. In this respect and with a view to facilitating comparison of figures between the different international settings, we suggest that prevalence data be reported both overall and for specific subpopulations (patients with ETT, AAs, VMNI, patients without AAs or ETT, etc.). This would serve to ensure that the profile of patients admitted to an ICU was reflected more clearly (a matter of maximum importance in the subject of study, given the close relationship between PR use and presence of ETT in critical patients).

Our data also highlight a prevalence of 25.17% in patients with neither AA nor NIMV, an initially unexpected finding, in that it is not justified by the use profile attributed a priori, i.e., to prevent self-removal of ETT. This finding could be accounted for, both by routine use of PR in ICU, and by the existing PR use policies at some units. In the former case, routine of PR use could justify their frequent application to patients not wearing life-sustaining devices in a number of different situations. With respect to the latter case, the sample showed that PR were used as a matter of ICU policy in as many as 33.68% of cases, i.e., under tacit agreements that lay down that all patients with ETT must have PR in place (regardless of their sedation/agitation status). In both cases, these would constitute situations far removed from the reflexive and individualised PR use currently being advocated4,5,43.

As pointed out, the differences in prevalence observed among ICU are important but do not appear to be related, in our case, to nurse:patient ratios. Although some authors have initially highlighted this ratio as a variable associated with increased application of PR, other studies report wide differences in the use of restraints in countries which have the same ratios as the UK or northern European countries, whose average nurse:patient ratio is 1:1, and which, in addition, incorporate specialised practitioners such as respiratory therapists into their staff complement2,28. Even so, we agree with Luk et al. and Kandeel & Attia in stating that, despite the fact that an optimal nurse:patient ratio is more than desirable, the a priori effect on prevalence of PR attributed to the ratio may not be quite so decisive6,28,44. Insofar as ICU staff profiles are concerned, apart from the nurse:patient ratio, a number of authors underscore the importance of expertise in ICU and their degree of training in decision-making vis-à-vis PR use24,35,45. In our case, no statistically significant relationship was found between prevalence of PR use and health professional training, a finding which can be explained by the low proportion of ICU with specific training in PR use. At all events, this relationship should be examined in greater depth, both as regards PR prevalence and application quality, taking into account the influence exerted on staff by the culture developed at each ICU6,24,36.

Data referring to indications of use, location or adverse effects are, on the whole, in line with those reported in the literature1,2,8,28. As regards behavioural changes observed as being adverse effects to application of PR, it is worth noting that, though the main indications of use were control of agitation and delirium, only 9.12% of patients presented with improvement in such symptoms versus 35% among whom these worsened. This same effect is also described by other authors30,45,46,47. Furthermore, Guenette et al. and Kandeel and Attia, on evaluating the effectiveness of PR and pharmacological interventions in the control of patient behaviour, conclude that, while application of PR maintains or exacerbates agitation, it is pharmacological interventions that actually achieve this control44,46.

Our study examined adherence to existing guidelines governing the application of PR, which have been embodied in 15 criteria grouped under the variable “Degree of adherence to guidelines for PR use”9,18,19,48. Stress should be laid on the high percentage of compliance with criteria, such as those pertaining to pharmacological management, which, as mentioned above, is showing itself to be partially effective in reducing PR use.49 In contrast, however, important deficits are observed in compliance with non-pharmacological management criteria (situational, verbal restraint, psychological, structural), which are cited by professionals as being crucial for prevention of PR use6,8,20,37,43,50. Lastly, it should be noted that the absence of a medical prescription for the measure, a request for written informed consent or any record in the CR, is in line with studies undertaken in countries which report a high use of PR and/or which have failed to adopt an institutional stance on the matter2,8,22,30,33,37,44. Furthermore, there are studies which report that, despite official institutional stances and even legal regulations, there is a gap between these and clinical practice, due to the complexity of PR use, thus calling for an interdisciplinary approach and shared decision-making23,51,52.

The most frequent indications of use are agitation or attempted removal of AAs and other devices, which could be related to the pain or delirium experienced3,4,22,53. Like other authors, our data show that the monitoring of pain in non-communicative patients, and of delirium, are the least used elements in interpretation of patient behaviour30,54–56. However, the correlation found between appropriate pain monitoring in non-communicative patients and low prevalence of PR use is noteworthy. A more accurate understanding of pain behaviours in non-communicative patients (tense face muscles, frequent movements, heightened muscle tone, lack of adaptation to mechanical ventilation, etc.) makes it possible to get closer to a better diagnosis and treatment of the condition, and get away from the generic diagnostic label of “agitated patient”, under which PR are sometimes applied in a manner that is far from reasoned. This same result might have been expected in the case of monitoring of delirium, but the low prevalence of appropriate monitoring of the latter in our sample did not allow for analysis. This idea seems to be reinforced with the results of previous studies, in which appropriate detection of pain (in communicative and non-communicative patients alike) and delirium would diminish the clinical profile of agitation and reduce the need for PR20,23,24.

Lastly, when it comes to institutional involvement, a lack of attention has been detected in terms of implementation of protocols, specific PR management training, and alternatives in ICU, issues proposed as powerful tools of change in PR use7,8,18,19,22,24,35,48,57,58. These results appear to be in line with those found in other countries with a high prevalence of PR in ICU, thus bringing us back to routine use of PR in ICU2,18,22,33,37.

LimitationsThis study, which was supported by the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (Sociedad Española de Enfermería de Intensivos y Unidades Coronarias /SEEIUC) displays certain limitations.

The first of these relates to the fact that the inclusion of ICU which voluntarily consented to participate might have amounted to selecting those most intent on analysing their situation, thereby giving an excessively benevolent picture of PR use.

Furthermore, this was not a study designed to analyse self-removals and the data were collected in aggregate form, aspects which might limit a proper understanding of the phenomenon of study. In this respect, as Fig. 1 shows, attention should be drawn to the gradual decrease in PR use as the respective observation periods progressed (see ICU 5, 9 or 16). This phenomenon, which can be accounted for by the Hawthorne effect, indicates the possibility of a reduction in PR use without a rise in patient safety/security incidents, a situation also observed by Hevener et al7,58. Moreover, the very fact of conducting studies on PR management is in itself an awareness-raising element with respect to the participating clinicians, stimulating critical reflection on professional practice and spurring change.

It should be recalled that the data were collected in 2016. Since then, advances have been made in various aspects that could be exerting some influences on the subject of study, e.g., the benefits of family presence in ICU or the adoption of “open-door ICU” policies at some hospitals. It is only in recent years that some evidence has begun to be generated about the family being a protective factor in terms of prevention and management of delirium, which could, intuitively, also be attributed to PR use.

This study, designed as a clinical audit, sought to obtain a real picture in a large sample of an issue little explored in Spain. The design has some limitations linked to the poor definition of some aspects of the sample, such as the profile of health professionals (years of expertise or degree of training), severity of patients measured with some validated instrument, or assessment of nurse workload measured more accurately (and not only via the nurse:patient ratio). We suggest that in the case of future studies, these parameters should be taken into consideration.

Lastly, the proposed criteria set, “Degree of adherence to guidelines for PR use” is a model created by the authors on the basis of their literature review and knowledge of the subject; it has not undergone validation and must therefore be approached with caution and be reviewed and revised from a more up-to-date perspective, e.g., with concepts such as patients being on analgesics being replaced by quantification with validated tools (objective values of VAS/NVS or ESCID/BPS/CPOT). In addition, thought should be given to assessing the pertinence of establishing cut points in the degree of compliance with optimal use criteria, so as to facilitate the model’s translation into clinical and management practice.

ConclusionThis study shows the reality of PR use in a setting which might be similar to that of other countries with frequent use of PR. While restraints are especially frequent among patients with ETT/AAs, they are also present in other patients who, a priori, do not respond to the attributed profile of use. Non-pharmacological alternatives to PR use, surveillance of ethical and legal aspects relating to such use, and institutional involvement are proposed as elements with ample room for improvement. Optimisation of interpretation of patient behaviour with validated tools may constitute a limiting element on PR use in critical patients. There would seem to be a need: firstly, to review and revise the care protocols governing patients admitted to ICU who pose a risk in terms of self-removal of devices; and secondly, to train professionals in reasoned, individualised use of PR.

FundingAs winner of the First Prize for the Best National Care Research Study (2nd edition – November 2016), this study received funding from the Majadahonda Puerta de Hierro University Teaching Hospital(Madrid, Spain).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no commercial links which might pose a conflict of interests for the purposes of this study

The authors would like to thank the Spanish Society of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine and Coronary Units (Sociedad Española de Enfermería de Intensivos y Unidades Coronarias/SEEIUC) for supporting this study as an activity aimed at fostering the scientific and educational development of nurses in critical patient care.

Thanks must likewise go to Carmona-Monje F.J., Carrasco-Rodríguez-Rey L.F., García-González S., Heras-Lacalle G., Láiz-Diéz N., Lospitao-Gómez S., Martin-Rivera B.E., Martínez-Álvarez A., Rodríguez-Huerta M.D., Toraño-Olivera M.J. and Velasco-Sanz T.R. for their invaluable help with the collection/analysis of data, without which his study would not have been possible.