1) To explore the main characteristics of intensive care unit transition according to patients' lived experience and 2) To identify nursing therapeutics to facilitate patients' transition from the intensive care unit to the inpatient unit.

MethodologySecondary Analysis (SA) of the findings of a descriptive qualitative study on the experience of patients admitted to an ICU during the transition to the inpatient unit, based on the Nursing Transitions Theory. Data for the primary study were generated from 48 semi-structured interviews of patients who had survived critical illness in 3 tertiary university hospitals.

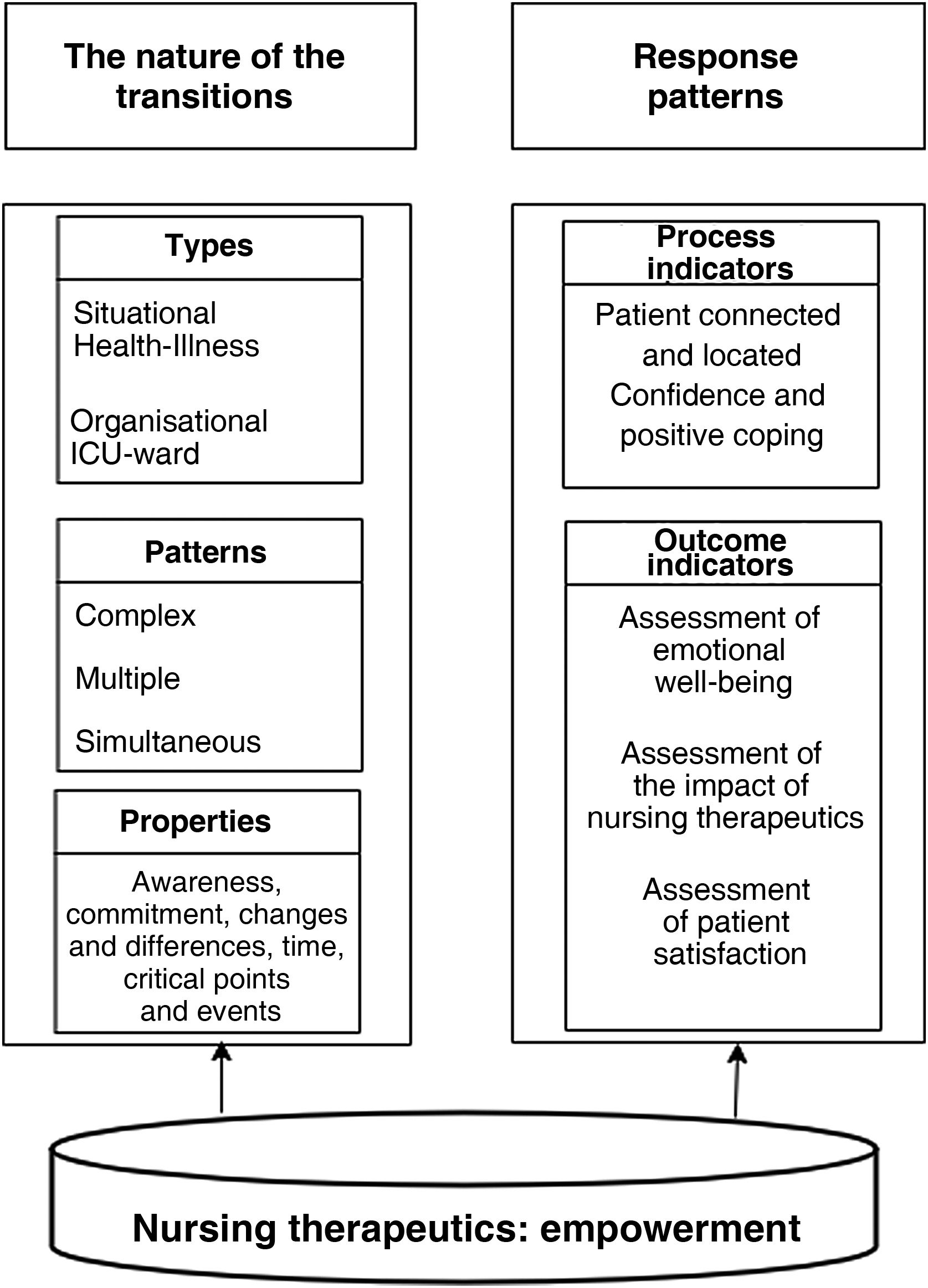

ResultsThree main themes were identified during the transition of patients from the intensive care unit to the inpatient unit: 1) nature of ICU transition, 2) response patterns and 3) nursing therapeutics. Nurse therapeutics incorporates information, education and promotion of patient autonomy; in addition to psychological and emotional support.

ConclusionsTransitions Theory as a theoretical framework helps to understand patients' experience during ICU transition. Empowerment nursing therapeutics integrates the dimensions aimed at meeting patients' needs and expectations during ICU discharge.

1) Explorar las principales características de la transición de la unidad de cuidados intensivos de acuerdo a la experiencia vivida de los pacientes y 2) Identificar la terapéutica enfermera para facilitar la transición de los pacientes desde la unidad de cuidados intensivos a la unidad de hospitalización.

MetodologíaAnálisis Secundario (AS) de los hallazgos de un estudio cualitativo descriptivo sobre la experiencia de los pacientes ingresados en una UCI durante la transición a la unidad de hospitalización, en base a la Teoría de las Transiciones de Enfermería. Los datos para el estudio primario se generaron de 48 entrevistas semiestructuradas de pacientes que habían sobrevivido a una enfermedad crítica en 3 hospitales universitarios de tercer nivel.

ResultadosSe identificaron 3 temas principales durante la transición de los pacientes de la unidad de cuidados intensivos a la unidad de hospitalización: 1) naturaleza de la transición de la UCI, 2) patrones de respuesta y 3) terapéutica enfermera. La terapéutica enfermera incorpora la información, educación y promoción de la autonomía del paciente; además del apoyo psicológico y emocional.

ConclusionesLa Teoría de las Transiciones como marco teórico ayuda a comprender la experiencia de los pacientes durante la transición de la UCI. La terapéutica enfermera de empoderamiento integra las dimensiones dirigidas a satisfacer las necesidades y expectativas de los pacientes durante la misma.

This research broadens understanding regarding the complexity of the patient’s transition from the ICU of those patients who have survived a critical illness.

Implications of the studyKnowledge of the main characteristics of ICU transition, as expressed by the patients themselves, will help nurses to develop nursing interventions, protocols, individualised care plans and policies in these units.

These interventions will help to reduce the negative complications of ICU transition in patients who have survived critical illness.

Furthermore, the findings of this study highlight the inclusion of new nursing roles such as advanced practice nurse, clinical nurse or liaison nurse to contribute to the reduction of complications and ensure continuity of care during the transition from ICU to inpatient unit.

Transition is a process of moving from one life phase, condition, or status to another, during which changes in health status, role relationships, expectations and abilities trigger a period of vulnerability in individuals.1 This vulnerability is related to experiences, interactions and environmental conditions of transition that expose individuals to potential harm, lengthy or problematic recovery, or harmful coping.2

One such transition is that of critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). The increase in the number of critically ill patients places a high demand on critical care beds, resulting in a rapid and sometimes sudden transfer of recovered patients from the ICU to other levels of care. There is an awareness that critical care beds are a scarce resource. Consequently, the decision to transfer patients depends not only on their physical condition, but also on the demand for beds. The transition from ICU to inpatient unit includes risks associated with readmission of patients to both ICU and inpatient units.3 In this regard, emphasis is being placed on analysing the transition from the ICU including post-ICU follow-up of these patients after discharge home.

It has been shown that the transition from the ICU can produce a period of vulnerability in patients,4–6 provoking various response patterns through observable or unobservable4 behaviours, such as emotional alterations, anxiety and depression.7 These changes are motivated by a sense of abandonment,8 insecurity,9 the aforementioned vulnerability,10 uncertainty and a sense of loss of control. The uncertainty associated with transition has been related to unfamiliarity and confusion about the meaning of the environment,11 about the meaning of health,12–14 or when an event cannot be adequately defined or categorised due to lack of information.15 This lack of information is an influencing factor during ICU transition.16–18 Loss of control, as another cause influencing patient behaviour, is also well described. The ICU patient has the feeling of being trapped in a situation where the care system takes control of his or her own life.19

The role of the nurse in transitional care situations is fundamental to the quality of care. Furthermore, the best practice guidelines developed by the Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario refer to care of individuals during transitions as a set of actions designed to ensure safe and effective coordination and continuity of care for individuals during a change in their health status.20

One of the nursing interventions described in the literature is empowerment. Empowerment is a process in which professionals use their knowledge to provide patients with the skills, resources, opportunities and power to change their own condition or circumstances21 and to develop independent problem-solving and decision-making skills.22 There are various definitions of empowerment,23–27 which have been increasingly adapted to nursing research, in some cases even becoming almost synonymous with the concept of nursing care.28 Empowerment in patients improves well-being,29 decreases anxiety and depression,30 improves self-care31 and quality of life.32,33 Likewise, the benefits of empowerment in ICU patients have been related to lower levels of distress and stress, greater sense of coherence and control over the situation, personal growth and development, and greater satisfaction.34

Furthermore, Afaf Meleis' theory of transitions offers a holistic perspective of the person experiencing a life transition35 and describes four main concepts of transitions: their nature, conditions, response patterns and nursing therapeutics.1,2 The nature of transitions includes the types, patterns and properties that characterise a transition; conditions are circumstances that facilitate or impede the achievement of a healthy transition; patient response patterns are conceptualised as process and outcome indicators; and nursing therapeutics constitute the nursing interventions applicable during transitions.1,2

Several transitions experienced in people's lives have recently been analysed on the basis of transition theory: the process of divorce,35 immigration,36 motherhood,37 transition from the neonatal ICU,38 menopause,39 transition of the nursing role40 or of elderly people in nursing homes.41 However, few studies42 have focused on analysing the ICU transition experience of patients who have survived critical illness from the perspective of transitions theory. This study presents a comprehensive framework that recognises the importance of ICU transition, identifies the main characteristics and proposes empowerment as an alternative to nursing therapy.

ObjectivesTo explore the characteristics of transition from the intensive care unit to the inpatient unit from the patient’s lived experience.

Identify the nursing therapeutics during of patients from the intensive care unit to the inpatient unit.

MethodologyStudy scopeThe study was carried out in 3 ICUs of three third level university hospitals in the metropolitan area of Barcelona: the Intensive Care Unit of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, the Traumatology ICU of Hospital Vall d'Hebron and the Cardiac Critical Care Unit of Hospital de Bellvitge. Between the 3 of them there were a total of 28 ICU beds in which the main diagnosis was medical (56%), the APACHE II severity level was 15 (3–45), the average length of stay was 10.6 days (2–44) and with a nurse: patient ratio of 1:2 and in the inpatient units of 1:7−12, and a nurse assistant: patient ratio in the ICU of 1:8 and in the inpatient units of 1:8−12.

ParticipantsPatients admitted to the different ICUs between September 2016 and January 2017 were included. Study participants were patients over 18 years of age, with more than 48 h of ICU stay, who spoke Spanish or Catalan and were able to conduct a personal interview and answer and complete the measurement instruments and informed consent. Patients who participated in the study were subsequently transferred to inpatient units. Patients with a previous diagnosis of mental illness did not participate in the study.

The primary study used a theoretical or purposive sample of maximum variation based on the following structural characteristics: gender, age, presence or not of family, presence or not of events (cardiopulmonary resuscitation, invasive diagnostic test, non-invasive mechanical ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, self-extubation, re-intubation, prone position and substitution therapies), presence or not of comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, haematological disease, oncological disease). Thus, 64 profiles were created based on these characteristics, resulting in an estimated sample size of between 128 and 192 participants. However, the final sample size was determined on the basis of information needs, taking into account the principle of theoretical saturation of the data from the different profiles, i.e., patients were interviewed up to the point where no new information was obtained.43,44

Data collectionIn-depth interviews45 were conducted in the corresponding ward between days 2–7 after discharge from the ICU. The interviews lasted 30−60 min and were conducted by the research nurses who had not cared for the patient during their stay in the ICU. The following questions were asked during the interview: 1) Could you describe in your own words your experience related to the transition process from the ICU to the inpatient unit, 2) What elements or conditions do you think facilitated or limited the ICU transition process for you, 3) What did you expect in relation to the ICU transfer process, and 4) What would you like to know before leaving the ICU?

All interviews were audio-recorded to ensure that no comments were lost and to facilitate subsequent analysis. In addition, the researcher's field diary was used to make notes of important events that occurred during the interview, which were then used to support the analysis.46 The interviews were then transcribed verbatim by each of the research nurses and entered into a qualitative data analysis software programme (NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2015).

Secondary analysisSecondary analysis (SA) of qualitative data was used.47 This research method aims to study a phenomenon on the basis of data collected in a previous study, thus providing answers to additional research questions that have not been developed in the primary study.47,48 SA may use a data set shared between researchers or may also involve the use of existing data collected in the primary study by the same principal investigator.47 Among the different types of SA, we have opted for analytical expansion for several reasons: first, the data collected in the primary study are sufficiently rich, from which several elements emerged that had not been analysed because they were not the subject of the main research questions, and second, because the reinterpretation of the data is carried out by the same researcher who conducted the primary study.49 Furthermore, it is considered appropriate to conduct a SA when the research objective is closely related to that of the primary study.50 In this SA, the questions are related to the analysis of the lived experiences of patients who survived a critical illness in order to delve into the dimensions of ICU transition proposed by Afaf Meleis' theory of transitions. Specifically, we use the data collected for a specific purpose for further theoretical development.

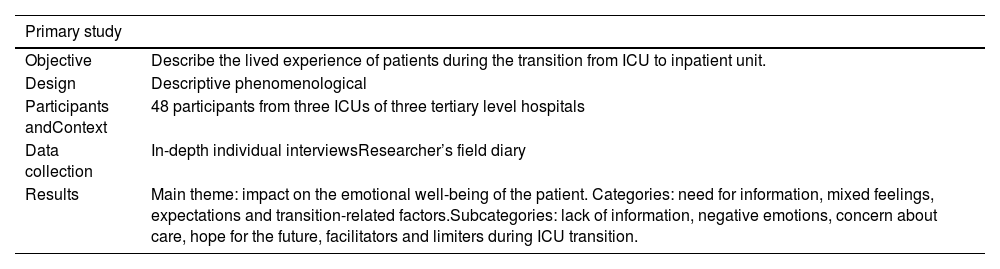

Data analysisRelevant aspects of the primary study are shown in Table 1. The research question for this SA was: What are the main characteristics of ICU transition according to patients' lived experience? Using the theoretical framework of transitions theory as a guide for the analysis of the main dimensions and concepts of ICU transition and the identification of a nursing therapeutic to help patients during ICU transition. Furthermore, the content analysis described by Graneheim & Lundman46,51 was used to determine meaning units, codes, subcategories, categories and themes. As a first step in the coding process, NVivo software was used as a support tool in accordance with the qualitative study design. The texts were originally coded into codes or nodes. The data themselves were reviewed for relevance to the new research question. As deemed appropriate, we retained the codes as a starting point for the SA.

Primary study description.

| Primary study | |

|---|---|

| Objective | Describe the lived experience of patients during the transition from ICU to inpatient unit. |

| Design | Descriptive phenomenological |

| Participants andContext | 48 participants from three ICUs of three tertiary level hospitals |

| Data collection | In-depth individual interviewsResearcher’s field diary |

| Results | Main theme: impact on the emotional well-being of the patient. Categories: need for information, mixed feelings, expectations and transition-related factors.Subcategories: lack of information, negative emotions, concern about care, hope for the future, facilitators and limiters during ICU transition. |

The main researcher coded all data related to the evidence from the primary study. It was not necessary to create additional nodes for the SA data because the original nodes were sufficient to answer the new research question. Each researcher at each hospital then reviewed the combined data within each of the primary nodes in new nodes. We created subcategories to analyse the dimensions and processes inherent in each of the top-level top nodes, grouping and regrouping codes at higher levels of abstraction. Two of the researchers reviewed, critiqued and discussed the analysis at each step, editing as necessary until consensus was reached on the analysis and conclusions.

AccuracyLincoln and Guba's criteria of credibility, transferability, reliability and confirmability52 were applied. To increase the representativeness of the results, patients with different profiles defined at baseline were included.53 Transferability was addressed by providing details of the data and the ICU transition context by reporting direct quotes from participants. The credibility of the data analysis was enhanced by having each of the researchers from the three centres critically analyse the data before reflecting on the analytical process to verify if there was a fit of the primary study data with the new research question. Reflexivity was maintained throughout through continuous documentation in the researcher's diary entries by comparing notes with the data and engaging in discussions with the whole team about the analysis.

ResultsForty-eight interviews were conducted, identifying three themes during the transition of patients from the ICU to the inpatient unit: 1) the nature of the transition from the ICU, 2) response patterns and 3) nursing therapeutics (Fig. 1). The following is an analysis of these issues based on the patients' experiences as expressed by the patients themselves.

Main secondary analysis (SA) themes.

Translated and adapted from Schumacher and Meleis.1

In relation to the transition from the ICU to the inpatient unit, patients expressed a feeling of security in the ICU, and a feeling of abandonment and disconnection between the two units (ICU-inpatient unit) as a lack of continuity of care in the destination unit. “There should be a link, a bit of contact and collaboration between the two teams to at least see if everything is running smoothly between one and the other. Because maybe what they foresee in the ICU, the doctor here or the infirmary here says no, that it's another way. So, of course, what I would want would be a link and continuity” (participant 2). “Nor could they accompany me and stay with me or come every day. It would have been easier for me, but it can't be like that, because there are people there who are in a very bad way. I don't know, leaving it was horrifying. Leaving them and leaving the security; but I understand that they can't do anything else” (participant 10). “They already told me: we'll come and see you. And no one has come. The only one I keep seeing is the guy with the crane, the one who was going to lift me up and he is the only one I have seen; but they said: we will come to see you, don't worry, we will come to see you; but of course (…). I say to him: give them my regards, give them my regards, tell them I remember them, tell them to come and see me. They are very busy and they have a lot of work…” (the patient cries) (participant 31).

When the patient has overcome the acute reason for admission to the ICU and is in the period of recovery and transition to another level of care, the patient is aware of and expresses the emotional changes and concerns of the perceived situation during the transition. “I'm a bit worried because I don't know what it will be like there, if I'm going to be in a room a bit like the ICU, I don't know if they will have a kind of ward, not with so much surveillance. I'm a bit nervous because I don't know where I'm going and where they'll put me. And, also, I see that they have to help me a lot and that makes me more nervous” (participant 27). “Now I have to go to another unknown place, I don't know if they are going to take good care of me or not (…) I'm scared, I'm very scared” (participant 31).

In terms of time, from the moment patients in the ICU are informed that they are recovered and of the imminent transfer to another unit, a period of time passes during which they experience various emotions. At first, they experienced instability and uncertainty, causing the patient confusion, stress, anxiety and sadness.

Time goes really slowly; it is better to say: “We are waiting for a report to see if you can leave. We've already called, if you don't leave today, you'll leave tomorrow”. That day it seems like you won't, but you can change your mind. You can get up and leave at that moment because 24 h is very long” (participant 19). “It's that everything scares you so much after being there, because so many things happened to me, and I thought that it would have to happen to me again or repeat itself. And I'm still afraid that something will happen again. When something hurts, I tell them: 'Look at my blood pressure, look at my temperature quickly'. And they tell me: “when we change shifts”. Then you get scared and I cry every day” (participant 10). “I'm thinking about what circumstances I will be there, how I will be there” (participant 27).

Finally, regarding critical points and events, the reason for admission to the ICU is a critical point that occurred when the patient was admitted to hospital, and the events that occurred during the stay in the ICU makes the patient become a dependent person, generating in the patient a feeling of loss of autonomy. “When you adapt to the fact that you can't move and that they have to help you to do things, that's what it is, you feel better and you want to do it yourself and they don't let you and that makes you nervous because it's like if I can get out of bed on my own, why do you have to help me, why?” “One of the things that made me want to go to the ward was to have more autonomy” (participant 9). “Not having autonomy, they did everything for me, the bed and everything. It was very suffocating” (participant 28).

Some patients state that the transition process from the ICU makes them feel impotent and irritable. “It made me feel helpless sometimes, when you talk to the staff, you get the feeling that you are not listened to, that there is a protocol, that there is a way of working and you don't matter” (participant 30).

Other patients reported that the lack of information during transition caused them distress. “Perhaps what I missed the most was more information about my process, how I would evolve (…) if I will be able to live the life I had (…) and that is all patience, and it is hard to assimilate. I do rehabilitation, I go to the speech therapist (…) but nobody told me that you have a month or two. It is very ambiguous and it makes you anxious (…)” (participant 35). “Just thinking that I couldn’t walk and what could happen and now I am afraid as well because I don’t know what I shall do when they discharge me, I am afraid too” (participant 20).

Nursing therapeutics refers to interventions made by nurses to increase patients' confidence and skills to facilitate ICU transition.

Patients pointed to information and education by professionals as the main nursing intervention during ICU transition. “I have never been in hospital, in other cases it is not so necessary perhaps; but it is necessary to explain a little about what going to the ward entails. It is not like being up there, because just like there, there was a nurse who also told me: “it is better there, you can move around, here in the ICU you are more oppressed because it is like a bunker”. Well, yes and no” (participant 15).

Psychological and emotional support was also expressed by patients as a necessary nursing intervention during ICU transition. “I found myself missing a bit more humanity and not saying: 'look, we'll take you up to the ward' and that's it. But I have been cared for. I don't have any complaints from anyone, but I need a bit more affection, a bit more support, you know? A bit more support” (participant 16). “And there are those who tell you that you can't and you can't and that's it. That's why there are things that are necessary. For example, in my case with young people, psychological and emotional support and information about what is happening” (participant 5).

This SA made it possible to complete the definition of the characteristics of ICU transition from the experience of patients during ICU transition and to identify empowerment as part of nursing therapy.

Taking into account the characteristics of a transition based on the theory of transitions, this SA has identified that, during the ICU transition, there is a situational, organisational and multiple type of transition. Situational, as patients experienced a health-illness transition from ICU admission, critical health diagnosis, recovery and rehabilitation process and ICU discharge. Organisational, as patients transitioned between two units, the ICU and the inpatient unit, each with its own organisational characteristics. In addition, patients experienced a multiple transition due to situational and organisational transition. Furthermore, patients were transferred from a resource-intensive level of care (ICU), which has the highest technology for monitoring and surveillance, with a ratio of 1 nurse to 2 patients, to a less resource-intensive level of care with a nurse:patient ratio of 1:8−12.

Another important finding was the patients' perception of a lack of continuity of care when they were transferred from the ICU to another unit. These findings were previously described in another study6 and could have been due to a lack of information and communication between professionals.17 In this sense, the transfer of information between professionals in both units, with the participation of the patient, would be a good strategy to reduce this perception of lack of continuity of care. In agreement with de Grood et al., ICU transition is one of the most complex and high-risk transitions18 and may disrupt the continuity of patient care. This finding is also consistent with the study by Vázquez-Calatayud and Portillo10 who stated that ICU transition is complex and can lead to patient instability and vulnerability. Therefore, further exploration of each of these characteristics has been essential to highlight the complexity of ICU transition. To address this complexity, initiatives to improve the quality of care during ICU transition must employ an interdisciplinary model involving all stakeholders (physicians, ICU/ward nurses and patient-families).

Analysing the properties of the transition experience has also allowed us to ascertain the causes of patients' response patterns. The change from an environment where the critically ill patient has been admitted urgently and where he/she has been monitored, treated, controlled and cared for exhaustively, to another environment where there is likely to be an incongruence between the patient's expectations and actual perceptions, or an incompatibility between his/her needs and the availability and access to the means to satisfy them,4 causes a state of instability in the patient generated by uncertainty. However, there are studies that report that the impact of admission to the ICU is felt more deeply by relatives than by the patients themselves.54,55 On the contrary, our findings are in agreement with another study in that the lack of knowledge of the current health situation caused by the lack of information causes uncertainty, fear and anxiety in patients.12 Here, Ramsay et al. concluded that the transition from patient dependency in the ICU to patient independence in the inpatient unit is a major source of distress42 and can be problematic from the perspective not only of patients, but also of relatives and nurses.56 Nursing intervention during ICU transition is therefore necessary.

Regarding patients' emotions, uncertainty has been identified in this SA as one of the causes that could produce negative patient emotions such as fear, anxiety, worry and depression. Uncertainty could act as a limiting factor during ICU transition and was identified as a lack of knowledge and information for patients to cope with it. In addition to information about the current situation, patients also demand information about the physical and mental consequences after the critical illness16 and therefore we should seek to meet the information needs during ICU transition to decrease the uncertainty expressed by patients. Facing extreme uncertainty leads to feelings of chaos and loss of control. In this sense, managing uncertainty is fundamental for the patient's adaptation to a new situation.

In relation to patient response patterns, like anxiety, irritability, stress and depression, they are common during ICU transition, as has been observed in other research investigaciones.7,8 These response patterns were conceptualised in the transitions theory as process and outcome indicators. According to this theory, process indicators involve feeling connected, being able to interact, being situated and located, developing confidence and positive coping.2 However, our findings show that during ICU transition some patients expressed uncertainty, irritability and feelings of disconnection. The ICU nurse visiting the patient in the inpatient unit would be beneficial in decreasing the sense of disconnection. Identification of process indicators in patients will allow early assessment and intervention by nurses. Furthermore, assessment of process indicators will facilitate outcome indicators,1 such as mastery of new skills and behaviours, and will be reflected in emotional well-being and patient satisfaction.17 These are strongly related to receiving adequate information during ICU transition.17 The development of new coping skills during this process could help patients during ICU transition. The higher the level of knowledge and skills acquired in a situation, the better the patient's adaptation and response. Integrative behaviours are manifested by emotional well-being and patient satisfaction and would correspond to the outcome indicators described in transitions theory. In this regard, Stelfox et al. found that patient satisfaction was strongly associated with receiving information, answering questions appropriately, a visit from the destination unit physician prior to transition, and nurse assessment shortly after arrival at the inpatient unit; also, the most common recommendations provided by patients to improve this transition process were to inform and educate about the transition before it occurs.17

Another important point from the patients' perspective is to regain autonomy and control over their current situation. Admission to the ICU where state-of-the-art technology is available can sometimes intervene in care without taking into account the patient's autonomy. Often professionals see the patient as a measurable object focusing on monitoring and quantitative data and not on the person. From the moment the patient is admitted to the ICU, he/she becomes dependent and this makes the patient feel a loss of autonomy. This feeling of loss of autonomy can lead to anxiety and depression in patients during the transition from ICU.

Finally, nursing intervention should help patients surviving critical illness to cope adequately with the complications they may experience during ICU transition. The development and implementation of an information and education intervention during ICU transition will help patients to develop the meaning of the transition experience, and contribute to decrease uncertainty and, consequently, anxiety.14 This intervention has to focus on facilitating the individual's transition process, and consists of helping the patient to adapt to and live with a new condition,2 to recognise their potential, their resources and learn new skills, as well as knowledge of their new health situation or problem in order to manage and cope positively with it. However, not all patients experience a negative transition and therefore nurses need to understand the patient's patterns of response during transition and identify the main characteristics of a transition in order to intervene and implement a care plan with individualised and person-centred care throughout the process. Involving and empowering the patient and fostering their autonomy are key elements in achieving a healthy transition. Finally, in order for nursing therapy to be optimised, psychological aspects of the patient should be taken into account, i.e., in addition to providing the patient with the necessary knowledge and promoting and encouraging their autonomy, the importance of the demand for psychological and emotional support has also been observed. These results support the evidence previously found37 and are suggested as an essential intervention during ICU transition. However, in a randomised clinical trial with psychological intervention, no changes in patient emotional well-being were demonstrated.57

To this effect, promoting patient autonomy could help to achieve better outcomes. Therefore, empowerment emerges as a key intervention during ICU transition in order for the patient to feel a sense of control over the situation and regain autonomy. The nurse empowerment intervention is a challenge for nurses involved in ICU patient transition in the face of an increasing workload. To this end more research would be needed to demonstrate its impact.

ConclusionsThis SA has highlighted 3 themes during the transition of patients from the ICU to the inpatient unit: 1) nature of ICU transition, 2) response patterns and 3) nursing therapeutics. The SA provided an opportunity to highlight and increase awareness of the complexity of ICU transition.

Empowerment, as nursing therapeutics, aimed at patients who have survived critical illness, integrates information, education and autonomy promotion, identified as the main nursing interventions during ICU transition; in addition to psychological and emotional support.

Ethical considerationsApproval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the three hospitals for the primary study. Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (HCB/2016/0484), Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge (PR209/16/070716) and Hospital Universitario Vall d'Hebron, -PR(ATR)197/2016-. Following the recommendations of key authors in SA47,48, it was not necessary to request a new consent from the participants because the question of the current study was within the question of the primary study, the same researcher of the first study also performed the SA, thus preserving confidentiality, and because the initial informed consent specified that the use of the data would be for research purposes.

Study limitationsThe main limitations that arise when using a SA method are related to methodological and ethical issues, but most of the time these problems are due to a researcher conducting the SA of a previous study that he/she did not carry out.48 With regard to methodological aspects, some authors state that one of the problems with SA design is that the researcher has no control over how the data were collected and, in terms of content, the data may not be exactly adequate for the purposes of the proposed research realize.58 In our case, we highlight the fact that these two methodological problems are not present in the context of the present study. On the one hand, we describe how the research process of the primary study was carried out, specifying the data collection. On the other hand, we show how the data of the primary study fit the research questions of the present study.

While the use of the SA has certain limitations, it also offers some strengths such as the fact that the patient narratives were entirely spontaneous as they responded to general questions about their experience during ICU transition, i.e., they were not specific questions to describe the characteristics of ICU transition. Another strength of the study is that the participants were collected from three hospitals and this could reinforce the transferability of the findings.

Implications and recommendations for clinical practiceThis SA has contributed to changing the approach to ICU transition by describing its characteristics and identifying its complexity for consideration in future research. Acknowledging the dimensions of ICU transition is fundamental to facilitate the transition of patients from the ICU to the inpatient unit. Assessment of patients during this process and the implementation of interventions focused on helping these patients could contribute to decreasing complications in ICU survivors. Similarly, the incorporation of ICU survivors' experience of ICU transition into the development of evidence-based protocols, care plans and emotional well-being programmes is needed. In addition, awareness of the complexity of ICU transition should help to improve clinical practice, support nurses' decision-making and enhance clinical reasoning and critical thinking towards the application of new nursing interventions such as patient empowerment during ICU transition. Similarly, the inclusion of new nursing roles such as advanced practice nurse, clinical nurse or ICU liaison nurse could be helpful for the development and implementation of this intervention.

FundingThis study was partially financed by the Fundación Enfermería y Sociedad (Barcelona, Spain) within the framework of Grants for Nursing Research (PR-248 /2017).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.