A Morgagni hernia (MH) is a very rare form of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (2–3% of all diaphragmatic hernias).1 This hernia defect is found in the anteromedial portion of the diaphragm, behind the sternocostal insertions. The presence thereof may give rise to the herniation of abdominal viscera (omentum, stomach, colon, liver and small intestine) toward the chest cavity. The hernia defect is usually small and clinically asymptomatic in the majority of patients, often being diagnosed incidentally in adults.

We report the case of a 54-year-old male patient with no significant personal history who attended the Emergency Department with abdominal pain lasting 24h, located in the epigastrium. The onset was sudden, continuous, intense and accompanied by nausea and vomiting, as well as tightness in the chest when lying down. Upon physical examination, the abdomen was found to be distended, tympanitic and painful, with guarding on palpation of the epigastrium.

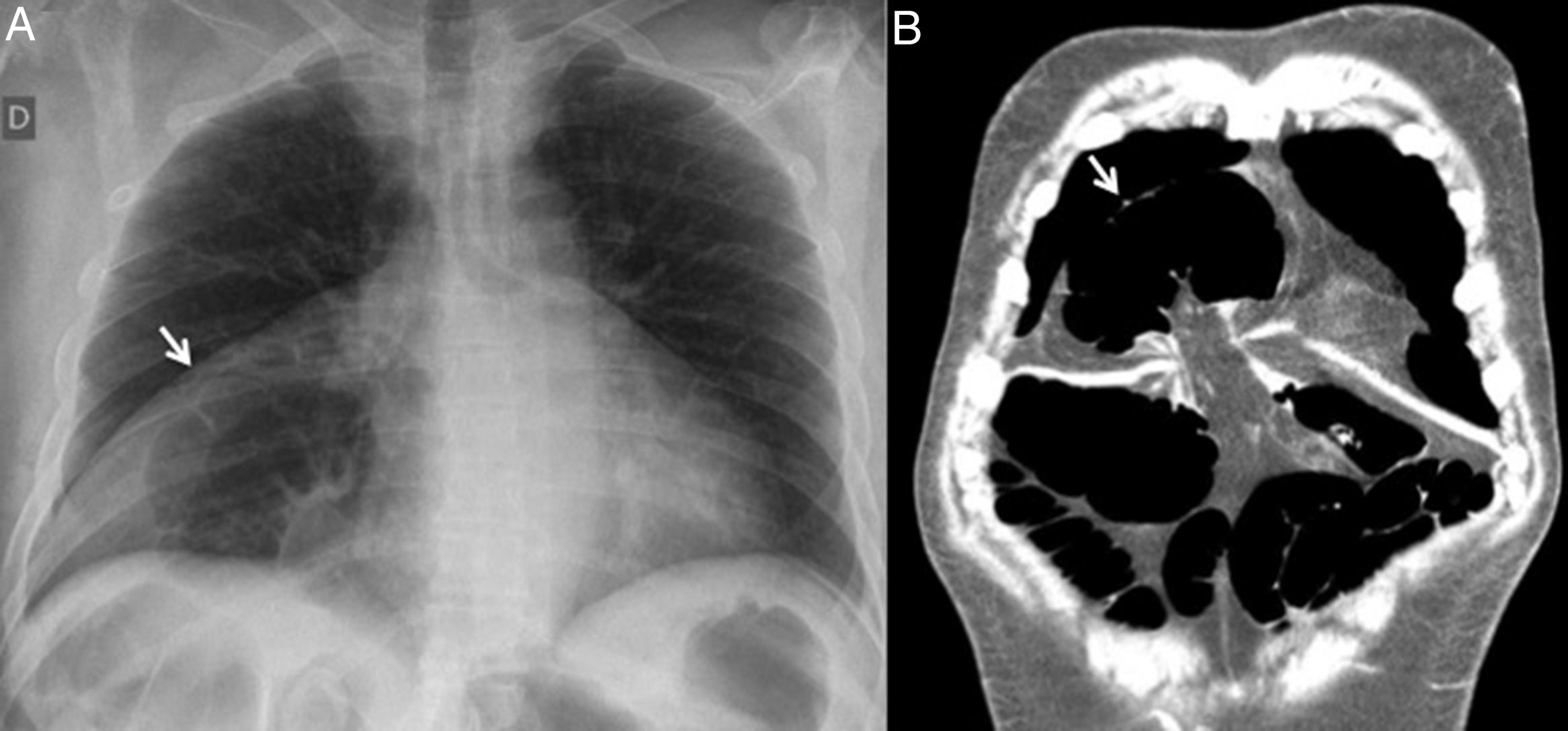

The chest X-ray revealed colon distension in the right hemithorax (Fig. 1A). Computed tomography (CT) was requested, revealing findings compatible with transverse colon herniation through a diaphragmatic orifice of around 3cm in the anteromedial portion of the right hemidiaphragm (Morgagni hernia). This led to a large-bowel obstruction with a competent ileocecal valve (Fig. 1B).

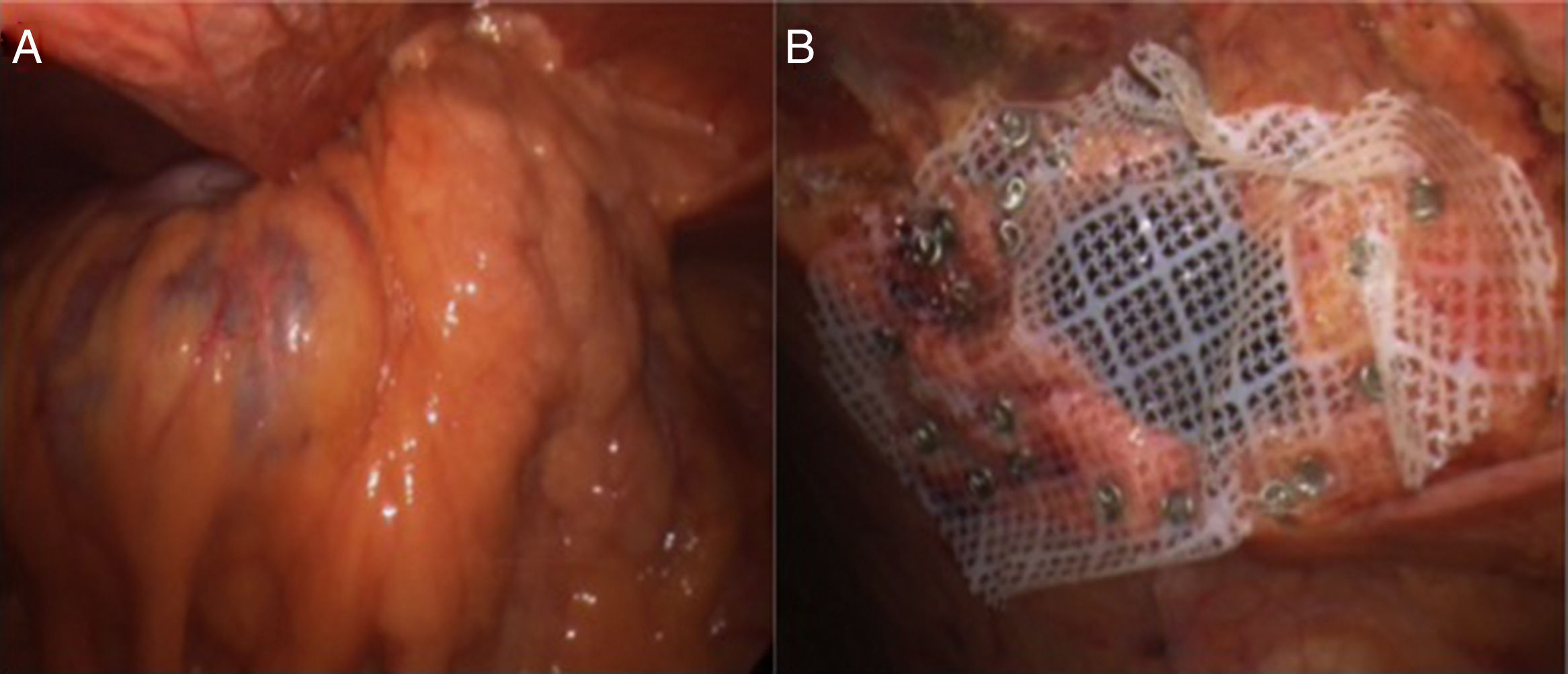

The patient underwent emergency laparoscopic surgery and the findings described on the CT scan were confirmed. The incarcerated transverse colon and omentum were then reduced, both of which proved viable and showed no signs of ischemia or perforation. Apposing the edges of the hernia defect was difficult and presented tension, so repair with a low-density condensed polytetrafluoroethylene mesh (Omyra® Mesh) was decided upon (Fig. 2A and B). Oral tolerance was initiated 12h post-surgery, with a positive clinical evolution, and the patient was discharged on the third day without complications.

The incidence of congenital diaphragmatic hernias is very low (1 in 2000 to 1 in 5000 live newborns),5 where MH represents less than 2–3%.1 The majority of cases relating to MH are diagnosed and repaired in childhood.2,3 MH has been linked to other congenital abnormalities such as congenital heart diseases, chest wall deformities, intestinal malrotation, omphalocele and chromosomal anomalies (trisomies 13, 18 and 21).4 A small number of these hernias (5%) are diagnosed as an incidental finding during chest X-rays on asymptomatic adult patients. Most authors recommend that they be surgically repaired due to the potential risk of incarceration, even in asymptomatic patients.5 However, incarcerated hernias are rare, with very few cases reported in the literature.6 In general, surgical correction is recommended, although there are disputes regarding the approach, hernia sac resection and the use of meshes.

Thoracotomy and, more frequently, laparotomy, were traditionally the standard surgical approaches. However, after Kuster et al. used laparoscopic surgery to repair a MH for the first time in 1992,7 minimally invasive surgery (including single-port and robot-assisted procedures) has been gaining ground and become the first-choice approach, since it is feasible, fast, safe and enables the patient to recover quickly and be discharged early.3,8–10 In urgent cases of incarcerated MH or in the presence of comorbidities, laparoscopic surgery is practicable, the patient's clinical and hemodynamic status permitting.

Some authors state that the transthoracic approach provides better exposure and a more optimal view of the phrenic nerve, with a safer hernia sac resection. However, most surgeons prefer to carry out the procedure via the transabdominal route since it is less invasive, as well as being quicker and easier.

Another point to consider is whether or not the hernia sac requires resection. Excision of the sac may result in a reduced recurrence rate, but can also be linked to a greater risk of complications (lesions of the pericardium, pleura, phrenic nerve and bleeding).5 Hernia sac resection is not currently deemed necessary in the majority of patients and should only be considered in specific cases.3 As regards the closure of the hernia defect, this differs in children and adults according to the series published on each of them. In the former, most authors consider repair using non-resorbable suture material with interrupted stitches to be the technique of choice, with low recurrence rates (2%).2 In adults, the current tendency is to perform a tension-free closure using a mesh, with good results.9

A case review of 298 adult MH patients shows thoracotomy to be the most widely used approach (49%), although laparoscopic repair is gaining popularity; the hernia sac is not removed in 69% of cases and a mesh is inserted in 64% of patients.10

In conclusion, we believe that the laparoscopic approach in patients with an incarcerated congenital diaphragmatic hernia offers notable advantages for both the surgeon – due to the excellent exposure of the surgical field – and the patient, with a low complication rate and early hospital discharge.

Please cite this article as: Casimiro Pérez JA, Afonso Luis N, Acosta Mérida MA, Fernández Quesada C, Marchena Gómez J. Oclusión intestinal secundaria a hernia de Morgagni incarcerada en un paciente adulto: una complicación infrecuente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:444–445.