Sleeve gastrectomy is one of the main treatments in bariatric surgery and other diseases.1 Despite its laparoscopic approach, it presents complications, one of the most common of which is staple line dehiscence (between 0.6% and 7%).2,3

Although dehiscence has traditionally been treated surgically, surgeons are increasingly opting for minimally invasive techniques such as external drainage of collections, placement of clips, biological glues, Ovesco clips, the OverStitch endoscopic suturing system and endoscopic placement of removable self-expanding metal stents.1,4–6

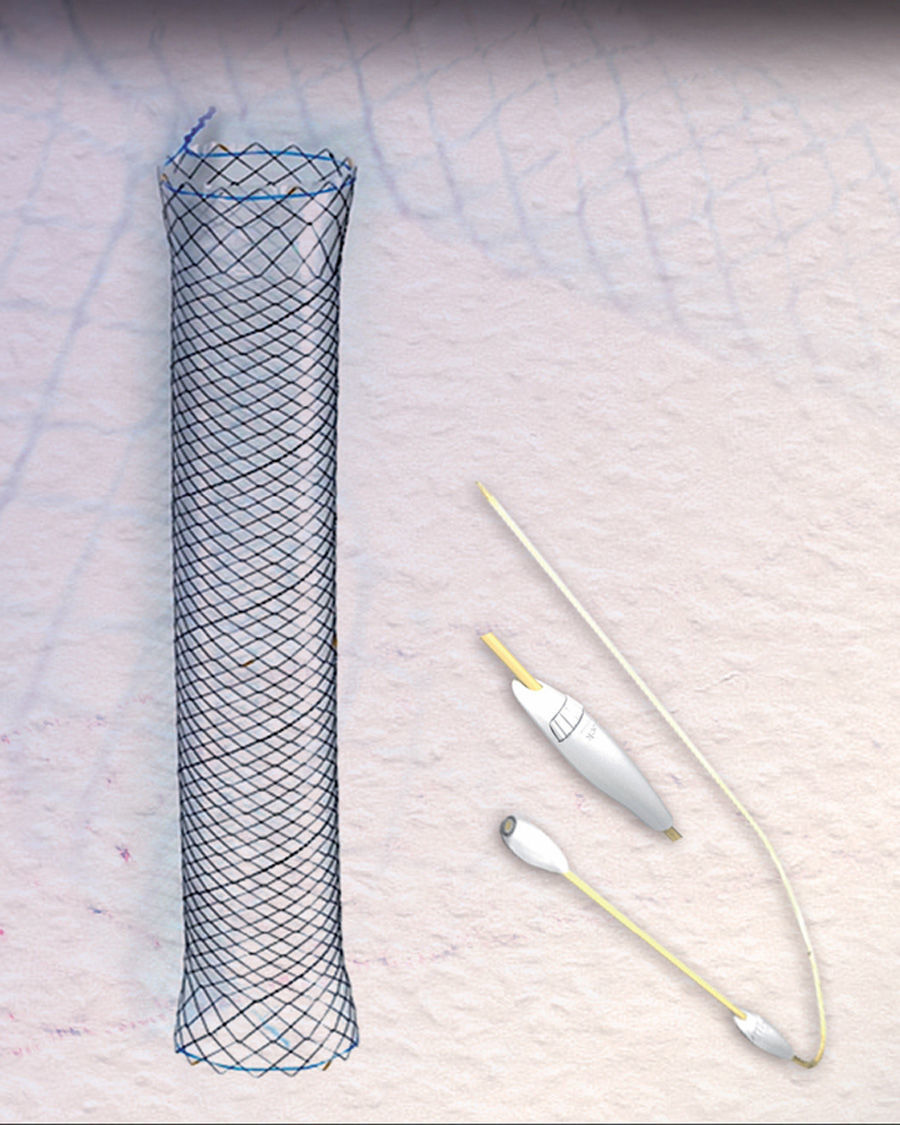

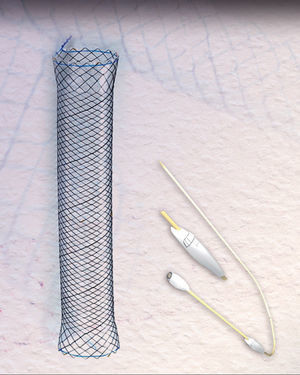

The success rate with these prostheses is approximately 80%, varying from 50% to 100% according to the series.4–10 However, migration and poor tolerance continue to present major limitations.4,5,7,10 A new, fully covered metal stent has become available in recent years, the HANAROSTENT Bariatric (Fig. 1), designed for patients with stable line dehiscence after sleeve gastrectomy. The shape is adapted to the anatomy of the surgical site and prevents stent migration, theoretically improving leak closure.

In order to test these alleged advantages with respect to previous stents, we used the HANAROSTENT in 3 patients. Surgery was laparoscopic with early hospital discharge (72–96hours post-surgery) following recovery of oral intake and oesophago-gastro-duodenal transit (EGDT) to rule out anastomotic leakage. We used the longest stent available (240mm) as it was the most suitable for covering the anastomotic areas of the oesophagus, sleeve and stomach. The stent was anchored in the pre-pyloric area in order to prevent migration, which was the main problem encountered with previous stents. A standard gastroscope was inserted under deep sedation, and the extraction and repositioning manoeuvres were carried out by pulling the ends using biopsy forceps. Correct placement was confirmed by radiological imaging. Tolerance of oral intake was initiated on the same day the stent was placed, with a liquid diet for the first 24hours followed by a soft diet; patients were discharged after 24–48hours, unless they required a longer stay due to dehiscence-related complications.

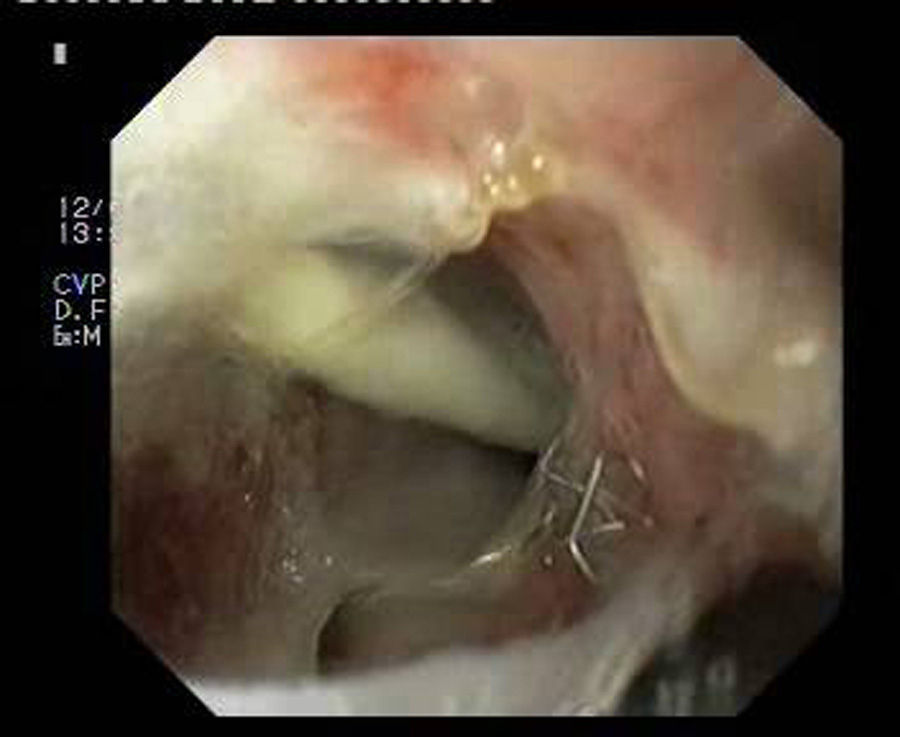

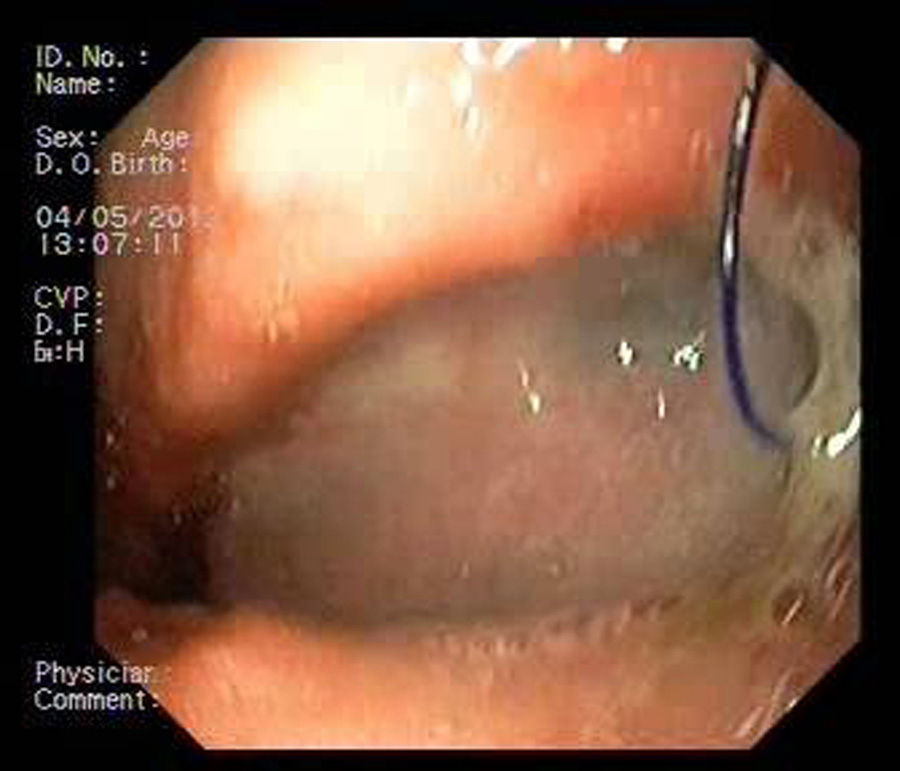

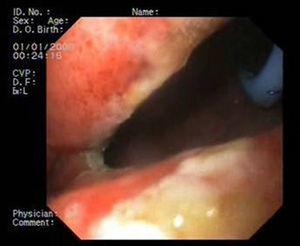

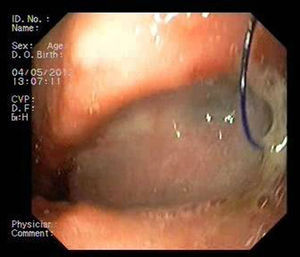

Patient 1A 46-year-old woman underwent surgery for morbid obesity. Ten days later, she presented abdominal pain. An intra-abdominal collection due to staple line dehiscence was observed; urgent surgery was performed to reinforce wound closure with sutures, leaving external drains. Two weeks later, given the high output through the drainage tube, gastroscopy was performed, which revealed extensive staple line dehiscence 40mm in diameter (Fig. 2). Eight weeks after surgery, it was eventually decided to place the stent and to initiate tolerance to oral intake. The follow-up X-ray revealed invagination of the metallic mesh towards the lumen, which was resolved with endoscopic mobilisation. Five weeks after placement, the stent was retrieved, observing complete closure of the fistula (Fig. 3). The patient presented retrosternal chest pain that was controlled with opioid analgesics.

Patient 2A 58-year-old woman underwent surgery for morbid obesity. After 3 months, a small leak was observed on EGDT; gastroscopy revealed 2 fistulous orifices in the anastomosis measuring less than 5mm. Given the small diameter of the openings, biological glue was applied endoscopically. Although the clinical outcome was very favourable, the fistulae could not be sealed, so 2.5 years after the surgery we decided to place a stent. The patient presented poor tolerance, and after 3 weeks the EGDT showed persistent leakage of contrast through the fistulous orifice, although the stent appeared to be correctly positioned. We decided to retrieve the stent, and observed on gastroscopy that it had become invaginated.

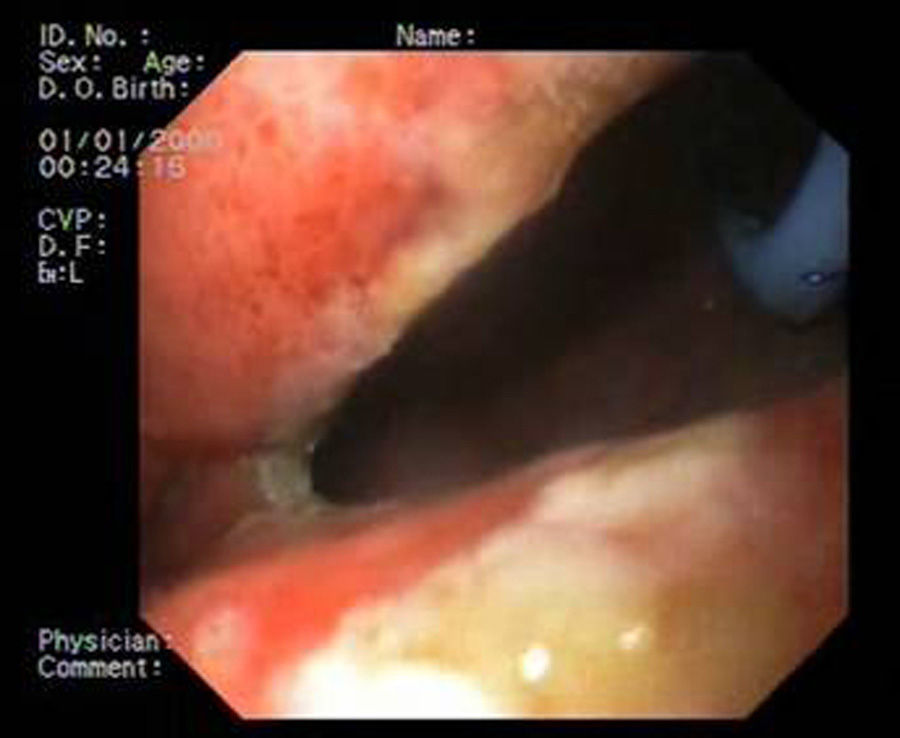

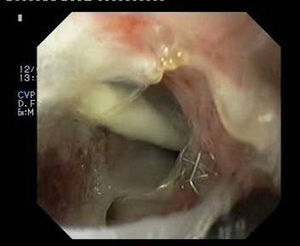

Patient 3A 64-year-old man underwent sleeve gastroscopy plus distal oesphaguectomy with oesophago-gastric anastomosis for adenocarcinoma of the lower third of the stomach. Two weeks later, he was admitted with pneumonia due to a para-oesophageal collection secondary to a leak in the region of the anastomosis as a result of staple line dehiscence measuring 30mm in diameter (Fig. 4). External drainage was performed, and the stent was placed 6 weeks after the surgery. Although it expanded correctly, angulation in the middle third persisted, which disappeared after endoscopic repositioning. Nevertheless, EGDT showed slight extravasation of contrast, with gastroscopy revealing a tear in the silicon membrane of the stent, which was sealed with cyanoacrylate spray. The stent was removed 6 weeks later, noting 2 small 2–3mm fistulous orifices remaining that were resolved with 3 sessions of biological glue (Fig. 5).

Technical success (capacity for correct placement, endoscopic mobilisation and extraction of the stent) was achieved in all 3 patients, and clinical success (resolution of the leak) in 2. The results described in the literature with respect to clinical success with the above stents are similar to ours.4–9

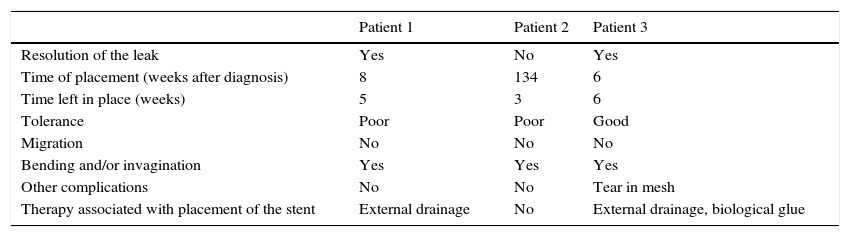

No immediate complications were observed. Late complications involved bending and/or invagination of the stent in all cases. In patient 3, a tear was observed in the silicone membrane of the stent, and 2 patients presented retrosternal chest pain. Nevertheless, no stent migration was observed (Table 1).

Outcomes with the HANAROSTENT® Bariatric stent in our 3 patients.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution of the leak | Yes | No | Yes |

| Time of placement (weeks after diagnosis) | 8 | 134 | 6 |

| Time left in place (weeks) | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Tolerance | Poor | Poor | Good |

| Migration | No | No | No |

| Bending and/or invagination | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Other complications | No | No | Tear in mesh |

| Therapy associated with placement of the stent | External drainage | No | External drainage, biological glue |

We believe that the therapeutic failure in patient 2 was related with late placement of the stent, as various studies have shown that successful leak closure is closely related with early insertion of the stent after the dehiscence.5,7,10 The stent also became invaginated. This was only observed during retrieval, and could also have contributed to therapeutic failure.

Combining stent placement with external drainage of collections in the acute phase, or the use of biological glues after retrieving the stent could increase its efficacy, as shown in patient 3. We also found that small tears in the stent can be effectively sealed with cyanoacrylate spray.

We tried to leave the stent in place for 6 weeks, as recommended in the literature.7,10 However, this was only possible in 1 patient. We should note that retrosternal chest pain prompted us to remove the stent in 2 patients: at week 5 in patient 1, because we believed—and later confirmed—that the fistula had closed; and at week 3 in patient 2, because given the persistence of the leak, we considered that it was not going to resolve by prolonging treatment. Therefore, although pain was a major problem, it could be controlled with analgesia and was not the only reason for early interruption of treatment in these 2 patients.

Although we did not observe migration of the stent, bending and invagination occurred, which were resolved with endoscopic repositioning of the prosthesis. We believe that both this and the poor tolerance were due to the long length of the stent that we chose, particularly in its oesophageal portion. The next step in the development of this stent will be to reduce the length of this portion, which will theoretically minimise these adverse effects. The question remains of whether these complications would have appeared if we had chosen a shorter stent, although we believe a shorter stent could have migrated.

We recommend early endoscopy after 24–48hours to check the correct placement and expansion of the stent, and later, whenever complications are suspected, as these are not always detected in radiological studies. If the stent is to remain in place for 6 weeks, we recommend gastroscopy at 4 weeks. This is because we observed a tendency towards decubitus mucosal hyperplasia, in which case mobilisation of the stent is useful to prevent fixation and facilitate subsequent retrieval.

Our limitations are the small sample size, and the fact that patients were initially managed by departments other than ours, thus making selection difficult.

We conclude that these stents should be considered for the early treatment of staple line dehiscence, because although we did not find them to be better than the previous prostheses (except for the absence of migration), the results obtained were encouraging. It is important to choose the size of stent that best fits the patient, to avoid intolerance and bending problems that make it difficult to close the fistulae. We believe that the next generation of these stents will increase the clinical success rate by reducing complications, although studies in this respect will be needed.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Alventosa Mateu C, Sempere García-Argüelles J, Suárez Callol P, Durá Ayet AB, Bort Pérez I, Quiles Teodoro F, et al. Experiencia con prótesis metálica autoexpandible con diseño específico para la dehiscencia de sutura tras gastrectomía tubular. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:460–463.