Extrauterine endometrial tissue is known as endometriosis, and is common in women of reproductive age.1 Endometrial lesions are found in genital organs and the pelvic peritoneum, but are also observed in gastrointestinal organs such as the omentum, in surgical scars, and in the mesenterium; they are found more rarely in the kidney, lungs and skin, and very rarely in the nasal cavity.2

Endometriosis of the appendix (EA) has been identified in less than 1% of patients with pelvic endometriosis.3 It is generally asymptomatic, and is associated with appendicitis, perforation and intussusception. An incidence of 0.05% in 71000 appendectomy specimens has been reported.4 We describe the case of a patient in whom EA was diagnosed during laparoscopy.

The patient was 38-years-old, gravida I, para I, and presented with a 9-month history of mild–moderate abdominal pain, which was constant, unrelated with the menstrual cycle and did not improve with common analgesics. Her menstruation was irregular-dysmenorrhoeic, and her last menstrual period was 12 days before admission. She reported no major medical or surgical history. Her general health was good, with normal vital signs. The abdomen was soft, palpable but painful on deep palpation predominantly in the right iliac fossa, and McBurney positive, with no frank evidence of peritoneal irritation; pelvic examination found no abnormalities. Plain abdominal X-ray showed no significant findings. Pelvic ultrasound revealed normal uterus and annexes. White cell count and percentage neutrophils were 8900mm3 and 67%, respectively. Urinalysis showed no pyuria or haematuria. Pregnancy test was negative.

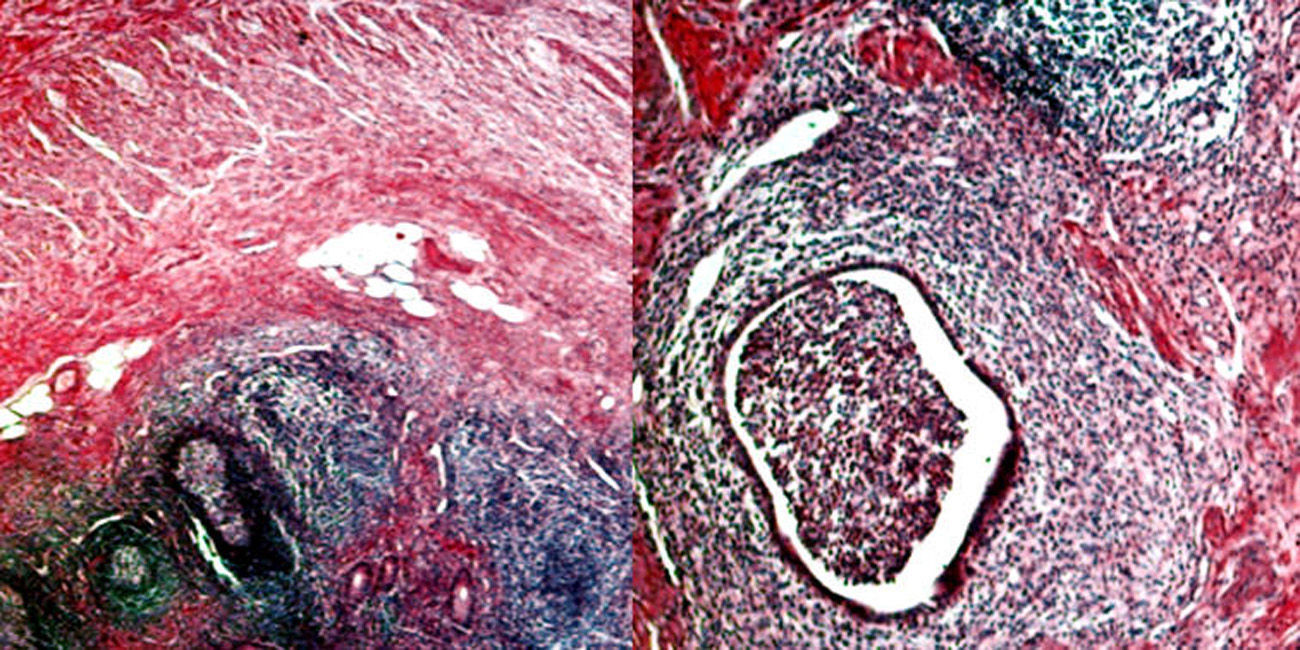

The patient underwent diagnostic laparoscopy for the chronic pelvic pain, in which normal uterus, ovaries and Fallopian tubes were observed, with some endometrial foci at the bottom of the pouch of Douglas, which were treated with electrocautery. The appendix was observed to be moderately congested, short, distended, irregular and oedematous, suggesting inflammation (Fig. 1), so appendectomy was performed. The patient was discharged on the third day. During her recovery, she reported a significant improvement in symptoms.

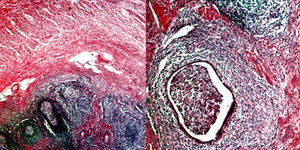

Histopathology analysis showed the presence of periglandular stroma consistent with endometrial stroma limited to the muscle and serosal layer (Fig. 2), confirming the diagnosis of EA.

EA is divided into primary and secondary forms. The primary form shows histopathological evidence of endometriosis within the appendix, with no clinical–pathological evidence of extra-appendicular endometriosis. The secondary form is associated with internal and/or external endometriosis. The majority of studies have pointed to similarities between appendiceal and tubo-ovarian endometriosis. Moreover, most patients diagnosed with EA suffer from menstrual irregularities and uterine myomatosis.5,6

Patients with EA can be divided into 4 groups, according to symptoms: patients with acute appendicitis, patients with invagination of the appendix, patients with atypical symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea and/or melaena) and asymptomatic patients. The most commonly observed group are patients who present with appendicitis, with the condition occurring mainly during menstruation.6 Symptoms are caused by endometrial bleeding within the seromuscular layer followed by oedema, obstruction and inflammation, leading to partial or complete occlusion of the appendiceal lumen.5

Diagnostic options such as patient history, physical examination, blood tests (CA-125), colonoscopy, ultrasound, tomography and magnetic resonance imaging may be useful for making the diagnosis of endometriosis. There are no imaging findings pathognomic of endometriosis.4 Definitive diagnosis is by biopsy of the endometrial implants. Although these are classically bluish-black lesions with variable degrees of pigmentation and peripheral fibrosis, most implants appear as non-pigmented lesions.7

The differential diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis includes inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, ileocolonic tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, benign and malignant neoplasms and colonic ischaemia.7

Histopathological evaluation is essential for the diagnosis of EA.8 Half of cases involve the body and the other half the tip of the appendix. The mucosa is generally not affected, while endometrial stroma and glands, like bleeding, are observed in the muscle and seromuscular layer in two-thirds of cases, and in the serous layer only in the other third.6

Treatment consists of surgery and hormone therapy based on the severity and type of symptoms. Preventing endometriosis is still not possible, so treatment begins with improving symptoms. Some patients are completely asymptomatic, and implants are found incidentally during surgery for other reasons. Laparoscopic surgery is useful in women with chronic abdominal pain, as in the present case, as it enables the entire peritoneal cavity to be explored and definitive diagnosis made. Laparoscopic appendectomy is the treatment of choice in these cases.5 Further medical treatment should be considered following surgery in patients with symptomatic endometriosis.7

Please cite this article as: Reyna-Villasmil E, Torres-Cepeda D, Labarca-Acosta M. Endometriosis del apéndice. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:463–465.