Fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis (FCDC) is characterised by the development of severe acute inflammation of the colon, associated with systemic toxicity. It is a clinical entity with high mortality that requires intensive medical treatment and early surgery in non-responders. The incidence of C. difficile infection—as well as its severity and mortality—has increased significantly in recent years.1 It is a common cause of infectious diarrhoea in hospitalised patients, and the main cause of antibiotic-induced diarrhoea. Symptoms vary from mild diarrhoea to potentially fatal fulminant disease; its diagnosis is based on the detection of toxins in faeces.

We present 2 clinical cases of FCDC. The first case was a 77-year-old man, immunocompromised as a result of chemotherapy and on treatment with metronidazole for C. difficile colitis for 12 days, who presented with acute abdominal pain, changes in his general condition, septic state and persistent diarrhoea. He also had haemodynamic instability, elevated blood lactate levels and Quick index of 57%. Abdominal examination was remarkable for diffuse pain with signs of peritoneal irritation. Plain abdominal X-ray revealed pneumoperitoneum and double wall sign (Fig. 1); urgent surgery was indicated, in which a perforated megacolon was found. Subtotal colectomy was performed, with ileostomy and mucous fistula. He was admitted to the intensive care unit for multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), remaining there for 7 days. He was treated with intravenous metronidazole and oral vancomycin, and made satisfactory progress. Macroscopic analysis of the surgical specimen showed signs of pseudomembraneous colitis (Fig. 2). He is currently awaiting intestinal passage reconstruction.

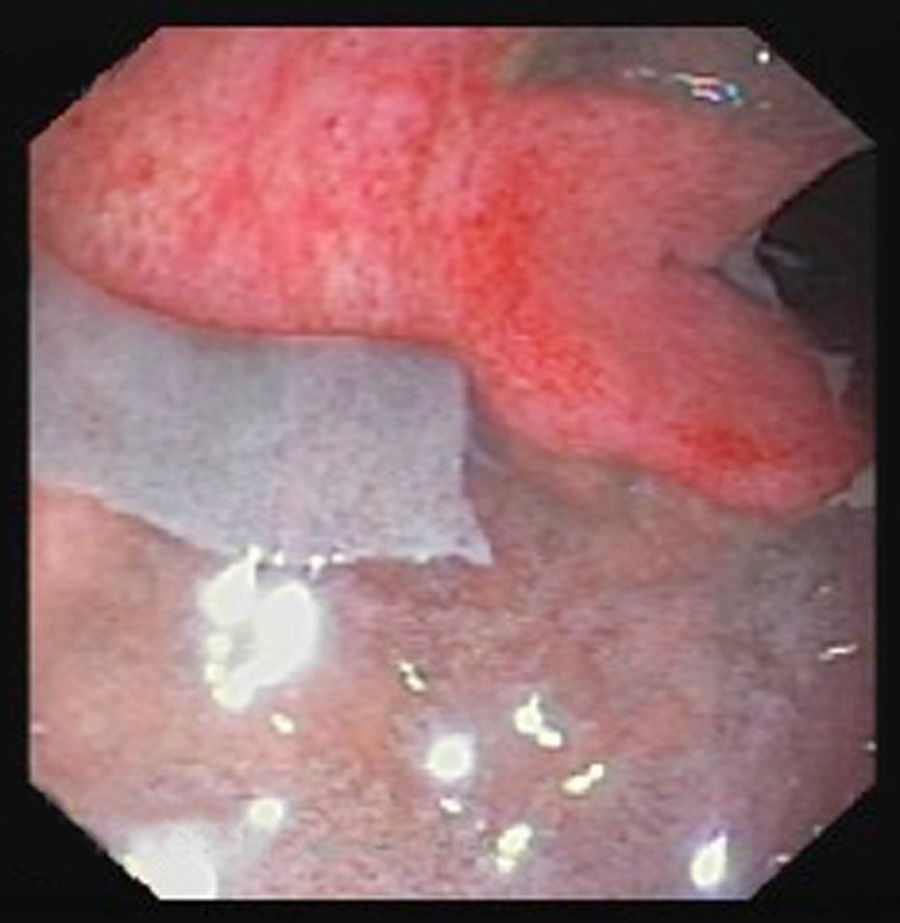

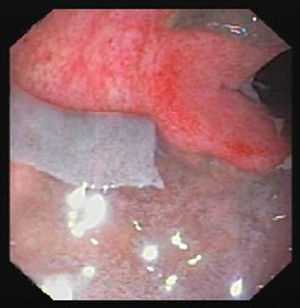

The second patient was a 57-year-old man who had been admitted to the surgery department following a right hemicolectomy for caecal cancer. He was admitted for febrile syndrome, treated with intravenous ertapenem 10 days prior to the intervention. On the first postoperative day, he passed a melaena stool with no analytical or haemodynamic effects. Hours later he presented a bloody stool with coffee ground vomitus and a drop in blood pressure. Urgent laboratory tests showed a fall in the Quick index and the red and white cell count. Emergency gastroscopy was normal, but following a new episode of massive rectorrhagia, the patient underwent urgent surgery. Intraoperative colonoscopy ruled out bleeding of the anastomosis, but found abundant traces of blood and a greyish mucosa, which detached easily (Fig. 3). Suspecting fulminant pseudomembraneous colitis, subtotal colectomy was performed with ileostomy and distal mucous fistula. Faecal samples were taken, where the diagnosis of C. difficile was confirmed after detecting toxin A and B by enzyme immunoassay, and the toxin B gene by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Recovery was favourable and months later the intestinal passage was reconstructed.

In addition to antibiotic treatment, other factors such as advanced age, chronic diseases, hospital stays or treatments with immunosuppressants, antacids and anti-peristaltics have been related with the development of C. difficile-associated disease.2,3 Another factor traditionally associated with this pathology is surgery and/or manipulation of the gastrointestinal tract,4 although in a recent study, only preoperative stent placement was identified as an independent factor in the multivariate analysis3, while the use and duration of oral vs intravenous antibiotics did not affect the incidence of colitis.

Evolution to FCDC develops in between 3% and 8% of infected patients. Although predicting the clinical course of the disease is difficult, factors predisposing to progression to FCDC have been identified, such as age, neoplastic disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, immunosuppression or history of inflammatory bowel disease.5 Identification of these factors may help select those patients who require intensive follow-up.

The timing of the surgical intervention is unquestionably a key factor in survival. Although there are clear situations that indicate urgent surgery, the exact moment is not defined and continues to be empirical to a large extent. Some authors6 have proposed a scoring system to identify patients who would benefit from an early surgical approach, jointly assessing clinical, analytical, radiological and therapeutic criteria.

All studies highlight the importance of surgery before the development of MODS.1,7 Subtotal colectomy with ileostomy provides the best outcomes.8 Different studies have suggested increased lactate, decreased serum albumin, age, need for vasopressors or immunosuppression as predictive factors of postoperative mortality.9 Perera et al.,10 after analysing multiple variables, concluded that only MODS is a predictive factor of mortality.

Our first patient presented predisposing factors to fulminant progression as a result of myeloma treatment. In the second, the symptoms of bleeding in the early postoperative period following colon surgery led us to suspect a surgical complication. It was only after the intraoperative endoscopy that the possibility of pseudomembraneous colitis was considered, later confirmed by laboratory tests and biopsies. Pathological review of the surgical specimen from the first intervention did not show any signs of infectious colitis. It should be highlighted that ertapenem has been associated with an increased risk of C. difficile infection.11

In conclusion, FCDC is a severe entity that requires high clinical suspicion and intensive therapeutic management. Multidisciplinary assessment is essential to establish the therapeutic measures and choose the best time for surgery.

Please cite this article as: Torrijo Gómez I, Uribe Quintana N, Catalá Llosa J, Raga Vázquez J, Sellés Dechent R, Martín Dieguez MC, et al. Colitis fulminante por Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:567–569.