The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a self-administered instrument for outpatients, but its behaviour differs according to the clinical population to which it is applied. In Mexico it is not validated in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

ObjectivesTo validate the HADS scale in the Mexican population with IBD.

Methods112 patients with IBD from the “Salvador Zubirán” National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition were included, to whom the HADS was applied and some demographic and clinical characteristics of the disease were evaluated. An exploratory factor analysis was performed and factorial congruence was calculated to determine the construct validity of the HADS, while reliability was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha.

ResultsThe result of the varimax rotation of the 14 items of the HADS explained 50.1% of the variance, having two main factors. Ten items showed high factor loading for the dimensions originally proposed. The internal consistency of the HADS was high (alpha=0.88) with high values for the congruence coefficients.

ConclusionsThe HADS scale is a valid instrument to detect possible cases of Anxiety and Depression in Mexican patients with IBD. The validation of this instrument allows its routine use for the integral evaluation of the patient and their timely referral to mental health.

La Escala de Ansiedad y Depresión Hospitalaria (HADS) es un instrumento autoadministrable para pacientes ambulatorios cuyo comportamiento difiere según la población clínica a la que se aplica. En México no está validada en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII).

ObjetivosValidar la HADS en la población mexicana con EII.

MétodosSe incluyeron 112 pacientes del Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición «Salvador Zubirán» con EII a los cuales se les aplicó la HADS y se valoraron algunas características demográficas y clínicas del padecimiento. Se realizó un análisis factorial exploratorio y obtención de la congruencia factorial para determinar la validez de constructo de la HADS y la confiabilidad se evaluó mediante el alfa de Cronbach.

ResultadosEl resultado de la rotación varimax de los 14 ítems de la HADS explicó el 50,1% de la varianza, teniendo 2 factores principales. Diez ítems mostraron altas cargas factoriales para las dimensiones originalmente propuestas. La consistencia interna de la HADS fue alta (alfa=0,88) con altos valores en los coeficientes de congruencia.

ConclusionesLa HADS es un instrumento válido para detectar posibles casos de ansiedad y depresión en pacientes mexicanos con EII. La validación de este instrumento permite su utilización rutinaria para la evaluación integral del paciente y su referencia oportuna a salud mental.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, both chronic diseases of unknown aetiology, involving genetic, environmental and immunological factors.1 Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease are characterised by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and a remitting/relapsing clinical course which has a significant impact on the individual's quality of life,2 working life,3 finances and mental health.4 Greater importance has been given to this aspect in recent years, as the incidence of emotional disorders is high in patients with IBD.5 Approximately, 19.1% of patients with IBD have anxiety and 21.2% depression,6 and these problems affect the clinical course and severity of the disease.7 The causes of this relationship may range from the complex interaction that takes place directly through the gut-brain axis8 to the development of other stressors, such as disturbed sleep pattern, which lead to an increase in inflammatory cytokines and acute phase reactants, triggering the inflammatory cascade and, consequently, altering the clinical course of the disease.9 Other studies have reported that patients with Crohn's disease who have depression or a generalised anxiety disorder are at an increased risk of needing surgery10 and, in general, depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with IBD are related to a larger number of relapses and less time between them.11 On the basis of these findings, it is therefore currently recommended that patients with IBD be assessed and appropriately treated for any psychological problems, as such interventions can improve their quality of life and reduce their relapse rate.8 This is particularly relevant when we consider the large discrepancies recently identified between the degree of importance the patient gives to the psychological aspects of IBD and the way the doctor perceives, detects and treats such aspects. These findings came from surveys in the ENMENTE project, which detected that healthcare personnel frequently reported not feeling qualified to detect this type of problem,12 and emphasise the role of effective mental health assessment in patients with IBD. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)13 is a self-administered instrument created to identify symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients without diagnosed psychiatric disorders. The items on the scale put more emphasis on the psychological rather than the somatic symptoms of anxiety and depression, which makes it easier to properly identify the symptoms and helps avoid errors of attribution to physical illnesses.14 The HADS has been used before in patients with IBD, with depression and anxiety reported in a large proportion of these patients (11% and 41%, respectively) and suffering from a disease with a severe clinical course, having been hospitalised due to relapses of IBD and financial deprivation identified as associated risk factors.15

The European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) now recognises the impact of psychological factors on the clinical course of both ulcerative colitis16 and Crohn's disease.17 In Spain, the Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa, GETECCU) and the Confederation of Associations of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (Confederación de Asociaciones de Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa, ACCU) have issued a series of recommendations, the most important of which is to investigate symptoms of anxiety and depression, and designate the HADS as the questionnaire with the best utility and applicability in the clinic setting for this purpose.18

In Mexico, IBD seems to be increasingly more common,19 so assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression which can dictate the clinical course of these disorders is extremely important. We therefore need to have instruments which are valid, reliable, effective and quick to apply for Mexican patients with IBD.

Since the original version was published in 1983,13 the HADS has been translated and validated in various countries and languages.20–22 The HADS was validated in Spain by Tejero et al. in 198623 and the high reliability and validity of the Spanish version was demonstrated in 2003.24 The scale has been validated in Mexico in populations with HIV,14 breast cancer,25 other cancers26 and obesity,28 and in carers of patients with cancer.27 However, it has been shown to have different clinimetric properties for each population. The constructs that each item aims to assess are not consistent in the different populations and the items are sometimes placed in dimensions other than those for which they were originally designed. The prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms reported in patients with IBD and the current recommendations for the detection of such symptoms in the clinic setting have therefore brought about the need to validate the HADS in Mexican patients diagnosed with IBD.

Materials and methodsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the “Salvador Zubirán” National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition (Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición «Salvador Zubirán», INCMNSZ). We conducted the study according to Good Clinical Practices. Patients from the IBD Outpatient Clinic were asked to verbally agree and sign the informed consent forms once the study objectives had been explained to them in depth. The confidentiality of their information was ensured and they were asked to complete the HADS questionnaire in a comfortable and private space prepared for that purpose. The following variables were recorded from the interview and medical records to enable us to study the characteristics of the sample: gender; age in years; schooling in years; whether or not they had been in a relationship with an emotionally stable partner for at least a year up to the time of the study; socioeconomic status established by the institute's social work department at the time of enrolment; whether or not they had been off work for two or more weeks at any time during the course of their disease because of IBD symptoms; and history of IBD-related surgery. We also classified the clinical course of their IBD as mild (initially active and then inactive), moderate (less than one relapse per year) or severe (more than two relapses per year).

SubjectsWe included patients over 18 who had been diagnosed with IBD confirmed by histopathology, attended the INCMNSZ IBD Outpatient Clinic and wished to participate in the study. They had to be able to read and write and not have been diagnosed with major depression or anxiety disorder at the time of the study; with that corroborated by medical records.

Assessment instrument and procedureThe HADS13 is a 14-item self-applied instrument consisting of a depression subscale and an anxiety subscale with interspersed items. Anhedonia is the central point of the assessment of the depression subscale as it is one of the primary symptoms for differentiating depression from anxiety. The items are scored on a 4-point Likert frequency scale (0–3) with a total score ranging from 0 to 21 on each subscale, where a higher score is indicative of greater symptom severity.

We collected the general demographic and clinical data of the patients who agreed to take part. The HADS was given to each of the patients and they were asked to answer each question according to how they had felt in the last seven days, including the day of the survey.

Statistical analysisThe demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are described with frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables and means and standard deviations (SD) for the continuous variables.

To test the clinimetric properties of the HADS (construct validity and reliability using internal consistency), we carried out the following procedures: (1) analysis of frequencies to determine whether or not all the items’ response options were relevant; (2) correlation matrix of the items and those with a coefficient lower than 0.20 were eliminated from subsequent analyses; (3) developed an exploratory factor analysis using a principal component analysis with varimax rotation; (4) once we had defined the HADS factor structure, we determined its internal consistency and that of the subscales obtained using Cronbach's alpha coefficient; and (5) last of all, we determined the factor congruence29,30 of the results obtained in this study and those reported in other populations. Version 22.0 of the SPSS statistical programme was used to perform the analyses.

ResultsCharacteristics of the sampleA total of 112 subjects were included, 41% (n=46) of whom were male and the remaining 59% (n=66) female. The average age of the sample was 44.4 (SD=15), with 12.9 years of schooling (SD=3.47), equivalent to completing secondary education. The majority of subjects had a partner (n=70; 62.5%) at the time of the study. Their socioeconomic status was medium (n=62; 55.3%) or low (n=43; 38.3%) and 25.8% (n=29) had needed time off work because of their IBD symptoms.

Of the subjects included, 85.7% (n=96) were diagnosed with ulcerative colitis and 14.3% (n=16) with Crohn's disease, 13 of whom (11.6%) had previously required surgery. At the time of the study, the clinical course of their disease was mild (initially active and then inactive) in 25.9% of the patients (n=29), moderate (less than one relapse a year) in 50% (n=56) and severe (more than two relapses a year) in the remaining 24.1% (n=27).

Construct validity and internal consistencyNone of the items that make up the HADS were eliminated, in accordance with the frequency analysis, for the analysis of its clinimetric properties; the correlation ranks between items were between 0.44 and 0.68. All 14 items were therefore included in the factor analysis.

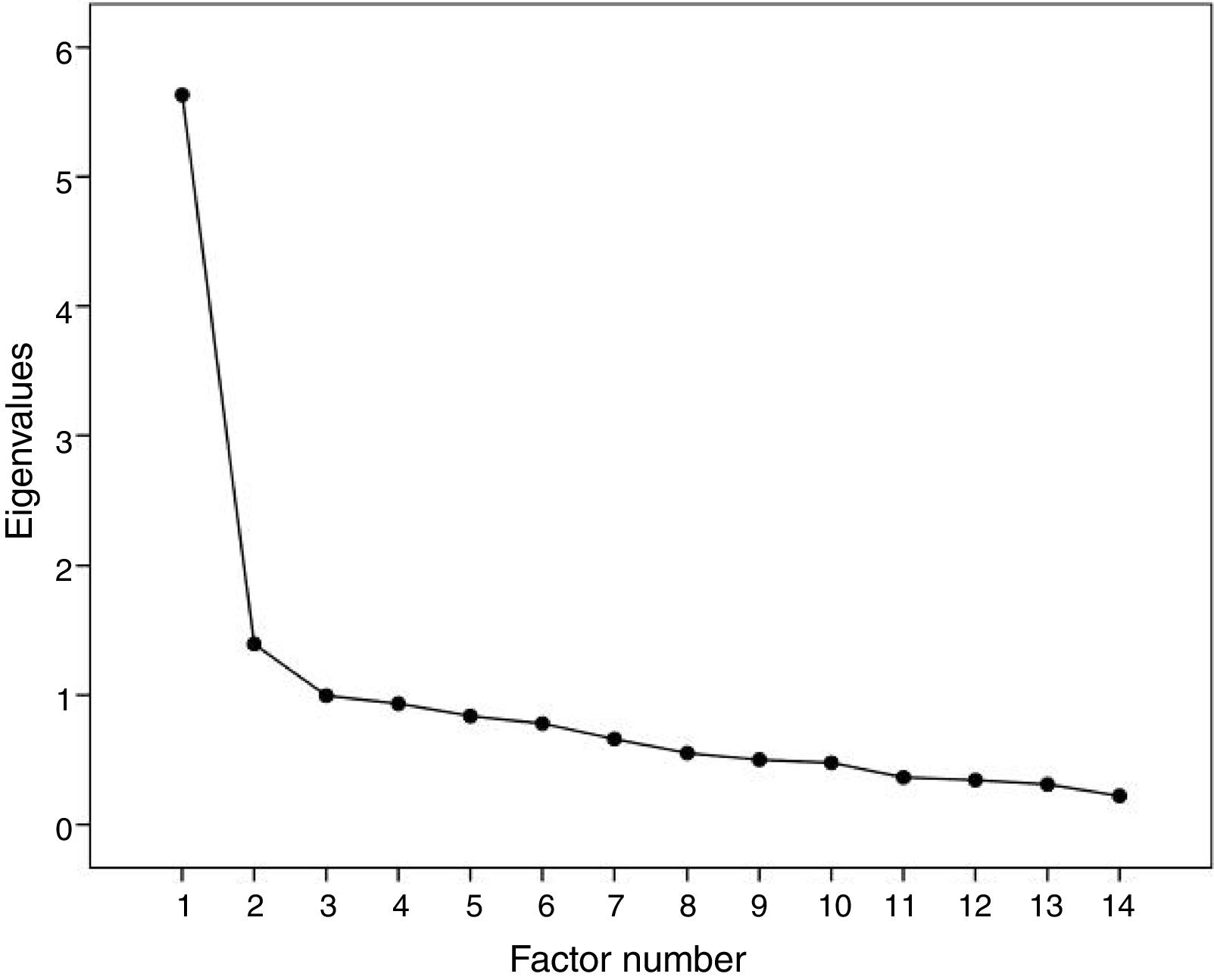

The results of the varimax rotation of the HADS items explained 50.1% of the variance, with an appropriate sample according to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value of 0.85 and a highly significant Bartlett sphericity test (p<0.001). The 14 items of the HADS were included in the model, yielding two factors with adequate communalities and corroborated by the sedimentation graph (Fig. 1).

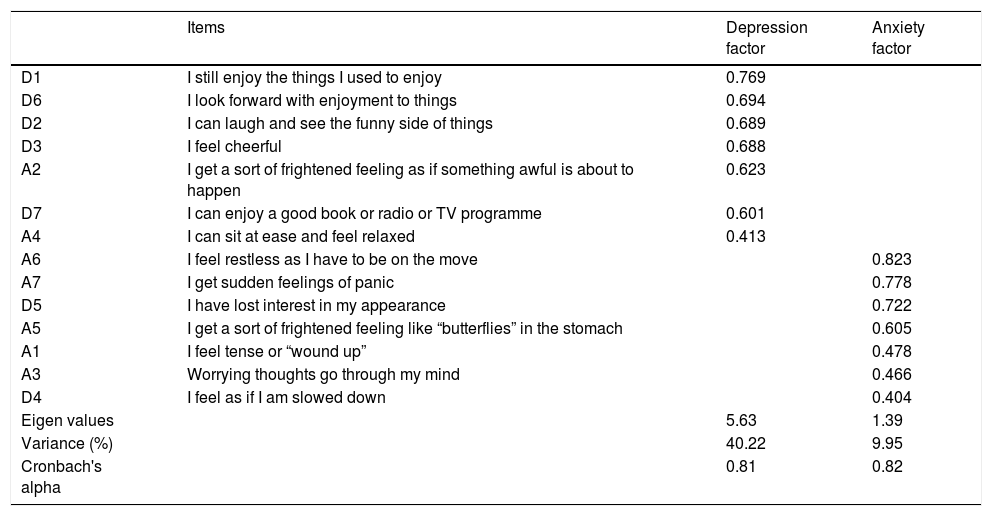

Of the 14 original items, 10 were in the originally proposed HADS dimensions. From the Anxiety dimension, items A2, “I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen” and A4, “I can sit at ease and feel relaxed” showed loading for the Depression factor, while items D4, “I feel as if I am slowed down” and D5, “I have lost interest in my appearance”, originally proposed for the Depression dimension, showed exclusive factor loading for the Anxiety factor. The internal consistency of the 14 items of the HADS evaluated by Cronbach's alpha was 0.88. High reliability values were also obtained for the Anxiety and Depression dimensions according to the factor model obtained in this study. The results of the factor analysis and the HADS internal consistency are shown in Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis and psychometric properties – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) 14 items.

| Items | Depression factor | Anxiety factor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy | 0.769 | |

| D6 | I look forward with enjoyment to things | 0.694 | |

| D2 | I can laugh and see the funny side of things | 0.689 | |

| D3 | I feel cheerful | 0.688 | |

| A2 | I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen | 0.623 | |

| D7 | I can enjoy a good book or radio or TV programme | 0.601 | |

| A4 | I can sit at ease and feel relaxed | 0.413 | |

| A6 | I feel restless as I have to be on the move | 0.823 | |

| A7 | I get sudden feelings of panic | 0.778 | |

| D5 | I have lost interest in my appearance | 0.722 | |

| A5 | I get a sort of frightened feeling like “butterflies” in the stomach | 0.605 | |

| A1 | I feel tense or “wound up” | 0.478 | |

| A3 | Worrying thoughts go through my mind | 0.466 | |

| D4 | I feel as if I am slowed down | 0.404 | |

| Eigen values | 5.63 | 1.39 | |

| Variance (%) | 40.22 | 9.95 | |

| Cronbach's alpha | 0.81 | 0.82 |

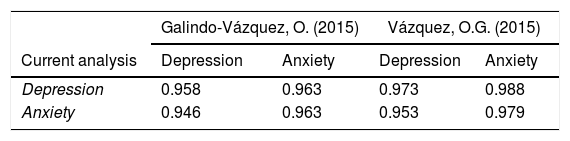

The factor congruence analysis was performed with the results obtained in a Mexican oncological patient population25 and in informal carers of cancer patients.26 The results show adequate coefficients of congruence, indicative of an appropriate cultural adaptation of the instrument in the population included in this study as well as a high correlation between the Anxiety and Depression factors (Table 2).

DiscussionOur results support the two-dimensional model of the HADS in non-psychiatric medical populations with adequate validity and reliability data to be used in the population with IBD.

As far as the results of the exploratory factor analysis carried out for the validation of the instrument are concerned, we can state that the factor loading of the Anxiety items A2, “I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something awful is about to happen” and A4, “I can sit at ease and feel relaxed” correlated with the Depression factor; similarly, the Depression items D5, “I have lost interest in my appearance” and D4, “I feel as if I am slowed down” correlated with the Anxiety factor. This is contrary to what was expected in relation to the original validation,13 but is consistent with what has happened in previous validations. For example, in their validation for primary carers of cancer patients, Galindo-Vázquez26 found some items correlated more than expected with the opposite factor to the one they intended to evaluate. Even in their validation for oncological patients, items A4 and D4 were eliminated from the scale because they had factor loading with a third factor independent of anxiety and depression, thus becoming problematic.26 In fact, item A4 was also found to be problematic in the study by Orozco-Nogueda et al.,14 as it also showed factor loading in an independent factor. This confirmed to us that the HADS and the constructs it evaluates are different according to the clinical population to which it is applied. Items A2 and A4 are related to activities that involve relaxation and it is possible that because of the symptoms of IBD, these items are associated with an affective response associated with sadness and not anxiety, while the items originally from the Depression subscale, D4 and D5, focused on mobility and personal appearance, cause a state of anxiety due to the inability to carry out activities that could be considered as part of everyday life. Another possibility is that, even though the items on the scale were designed with the aim of assessing the psychological symptoms of anxiety and depression as objectively as possible, their construction could make them very nonspecific in relation to what they are intended to assess and this may be causing patients to respond by associating the options presented to other types of experiences. This should be addressed in future studies to achieve a better understanding of the actual real lives of patients with IBD and the presence of symptoms of depression and anxiety.

In spite of the difficulties mentioned in some of the items of the HADS, the adequate reliability values and the congruence coefficients show us that it is a suitable instrument for assessing the presence of symptoms of depression and anxiety in this population. Similarly, the high correlation between anxiety and depression factors shows us that these two entities can appear jointly in patients with non-psychiatric medical illnesses and that, according to the literature, they may be underdiagnosed.31

Among the strengths of this study, we would point out that it is the first to assess the emotional aspects of IBD here in Mexico and that it validates the HADS, recognised as the questionnaire with the best utility and applicability for the clinic setting in Spain,18 as a useful tool for clinical application in Mexico. However, it is important to stress that future studies are necessary to confirm the validity of the instrument as a screening test for the diagnosis of depression and anxiety. The methodology used in this study and the lack of assessment by a healthcare professional or by other instruments already tested as diagnostic tools prevent us from being able to establish appropriate cut-off points for the HADS in terms of specifically determining a diagnosis.

Despite these limitations, our study provides a valid and reliable scale for making an initial assessment of the presence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in a population with IBD, further opening up channels to the multidisciplinary treatment that these patients may require for comprehensive management of their condition, and so improving their quality of life.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To Gianella Ramos-Cárdenas and Hernán Hernández-Ballesteros for their help in applying the questionnaires.

Please cite this article as: Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Sarmiento-Aguilar A, García-Alanis M, Gómez-García LE, Toledo-Mauriño J, Olivares-Guzmán L, et al. Escala de Ansiedad y Depresión Hospitalaria (HADS): Validación en pacientes mexicanos con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:477–482.