Oesophageal perforation is a rare, but very serious, complication of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGE). A rate of 0.06% has been reported for iatrogenic perforation in frontal-view endoscopy1 and the incidence is estimated to be two to three times higher in endoscopic retrograde cholangiography2 and endoscopic ultrasonography,1,3 due to the greater rigidity and diameter of the equipment and the lateral or oblique view, respectively.1–3

Pharyngoesophageal perforations are the least common type, with an incidence of 0.03%,3 occurring most often in the posterior part of the cricopharyngeus muscle, the pyriform sinus or Killian's dehiscence. Surgical management is the most used treatment strategy for these cases.4 There are also a few reports of conservative management, but these have involved prolonged hospital stays and the need for broad-spectrum antibiotics and parenteral nutrition.1,4

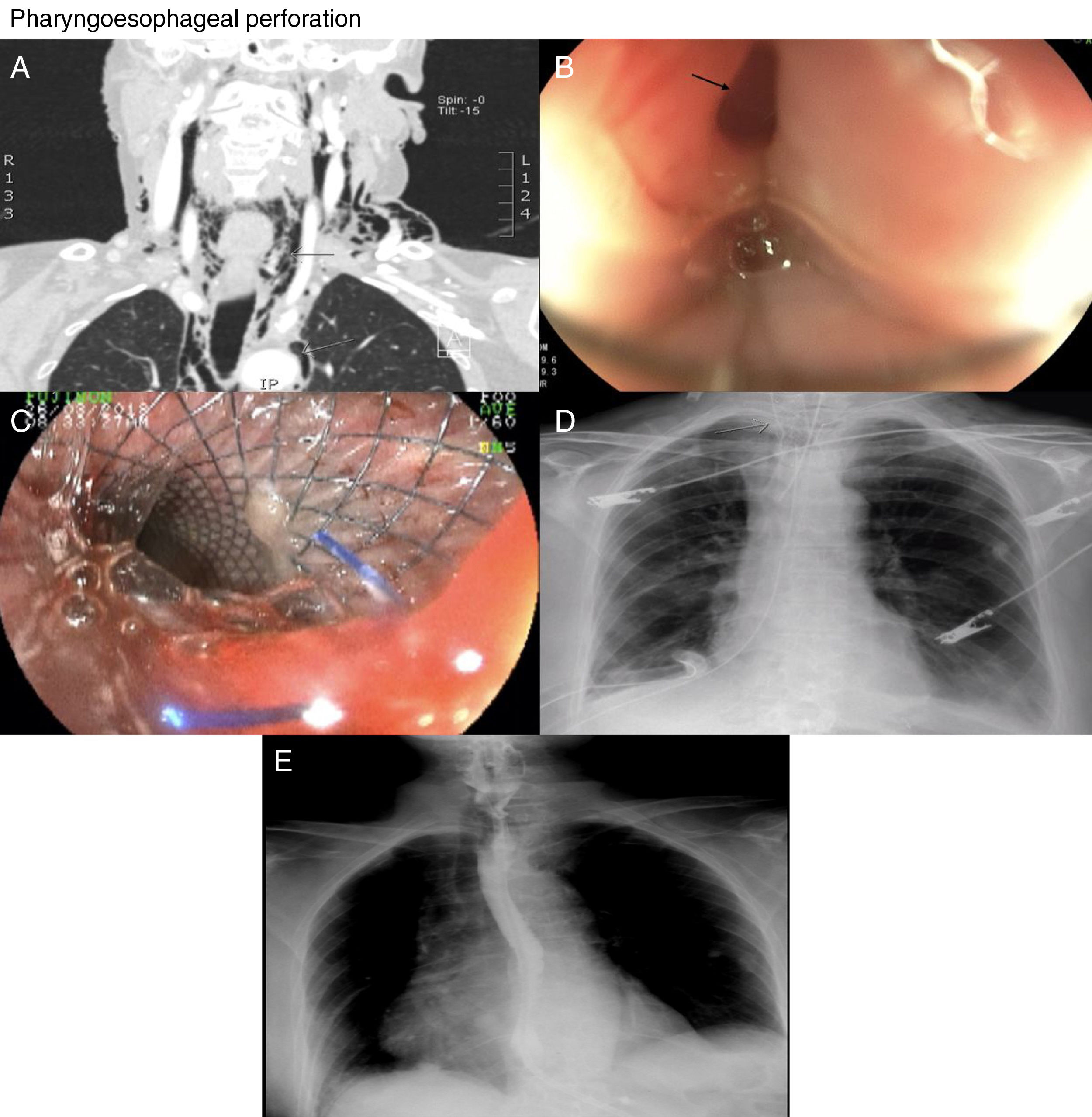

We present the case of a 70-year-old woman, who underwent an out-of-hospital UGE. The report described difficulty in passing into the pharyngoesophageal region and multiple failed attempts, for which they discontinued the procedure and discharged the patient from the endoscopy unit (she had iatrogenic perforation not noticed in that procedure). Twelve hours later, she went to Accident and Emergency with neck pain, hypersalivation and a “feeling of swelling in her neck”. In Accident and Emergency, subcutaneous emphysema was identified, with no other relevant clinical findings. Perforation was therefore suspected and a CT with contrast of the neck region revealed pneumomediastinum (Fig. 1A). A cervicotomy was performed with drainage of a scant amount of cervical and mediastinal fluid plus tissue from the anterior cervical oesophagus. The patient made poor progress due to fever, five days later requiring thoracostomy and drainage of cervical and mediastinal abscess; the perforation site was not identified during the surgical procedure. UGE identified a hole 1cm in diameter on the right pyriform sinus (Fig. 1B). A fully covered 18mm×8cm metal oesophageal stent (Wallflex®) was placed, leaving the proximal flare 2cm above the hole, close to the epiglottis (Fig. 1C and D). A nasogastric tube was also passed for nutrition. The correct position of the stent was verified by endoscopy and fluoroscopy. The patient was kept on mechanical ventilation with orotracheal intubation due to the position of the prosthesis, to avoid discomfort and allow diversion of the secretions towards the oesophagus. The removal of the prosthesis was scheduled for four days and went ahead as planned without incident. The patient made considerable improvement clinically, there was improvement in acute phase reactants, and repeat oesophagogram confirmed closure of the defect (Fig. 1E).

Pharyngoesophageal perforation. (A) CT scan of the neck with contrast: grey arrows showing evidence of subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum. (B) Black arrow indicating endoscopic evidence of hole in pharyngoesophageal region. (C) Endoscopic view of a metal stent in the pharyngoesophageal region. (D) Grey arrow showing radiological image of the stent in the cervical/thoracic region. (E) Oesophagogram: normal, with no evidence of contrast extravasation.

At her outpatient follow-up a week later, she reported dysphonia, odynophagia and mild dysphagia. She was given conventional analgesia and rehabilitation therapy instructions by phonoaudiology.

Pharyngoesophageal perforations cause bacterial translocation and formation of abscesses at the site of the break in continuity.1,4,5 Treatment therefore needs to be rapid and effective.

There is only one study in the literature which reports two cases where fully covered oesophageal prostheses were used in iatrogenic perforation of the pharyngoesophageal region.1 At present, there are no guidelines or consensus documents to cover this scenario. In a recent review, in an algorithm in first-line treatment, they propose surgical management with primary repair and drainage in acute perforation of the cervical oesophagus. If the repair is unsuccessful, a hybrid technique which includes repair with stent and surgical drainage would be indicated.4 In our case, the patient was taken to surgery for mediastinal abscess drainage, but the hole could not be identified. Taking into account the subacute clinical scenario, we considered closure with stent to divert the oral secretions and seal the defect mechanically. With the little information in the literature, how much time is required to seal the hole remains unclear, so we decided to leave it 24h longer than described by Kumbhari et al.1

Despite the limited evidence on endoscopic closure of iatrogenic perforation in the cervical oesophagus, from the data published so far, it seems to be a promising, safe and effective method that allows early discharge. The main limitation may be the need for this intervention to be performed in a hospital with an intensive care unit, as constant deep sedation and orotracheal intubation is required for at least 72h in these patients.

Please cite this article as: Mosquera-Klinger G, Torres Rincón R. Perforación iatrogénica faringoesofágica tratada con prótesis esofágica totalmente cubierta: reporte de caso. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:429–430.