Acute liver failure is characterised by the acute loss of liver function in a subject with no prior history of liver disease.1–3 However, this term should not be used in certain specific situations, such as in the event of prior liver disease, liver resection, liver injury secondary to trauma and where liver damage is caused by a systemic process such as shock or multiple organ failure with an aetiology other than primary liver failure.2 We conducted a retrospective, descriptive, observational study in a tertiary hospital to understand how this term is used as a diagnosis in patient discharge reports, both in cases where its use is appropriate, as well as in situations where its use is specifically not recommended.

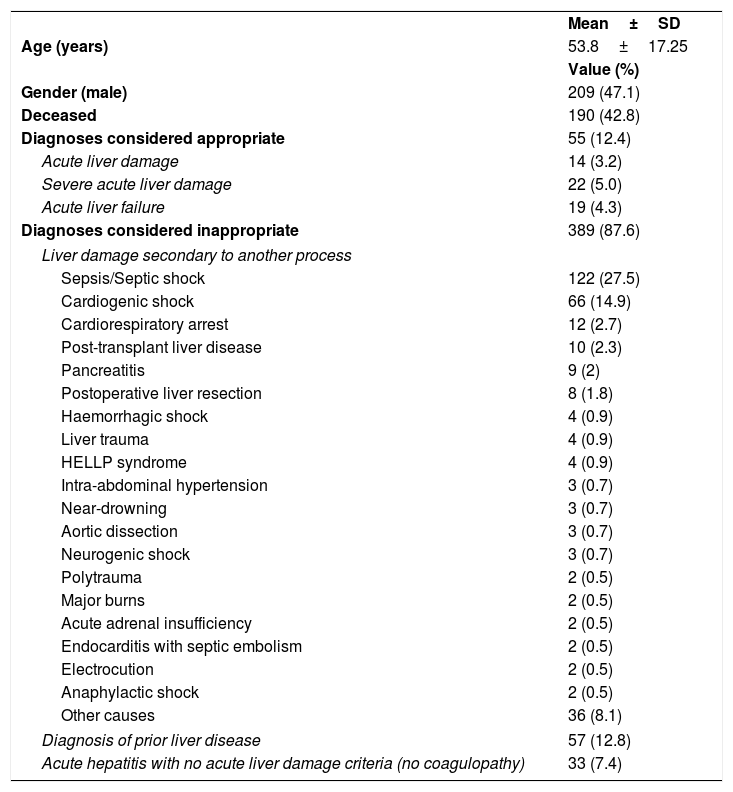

Patients aged ≥18 years diagnosed with liver failure or acute liver damage and who were admitted between 1 January 2007 and 30 September 2017 were included, irrespective of their other diagnoses. Patients were identified by searching the diagnoses specified on all the hospital's discharge reports. The study was approved by the corresponding Independent Ethics Committee. The diagnosis was considered appropriate if it met the criteria established by the European Association for the Study of the Liver's Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of acute (fulminant) liver failure.2 Acute liver damage was defined as elevated transaminase levels associated with coagulopathy, severe acute liver damage as an INR ≥1.5 and acute liver failure as the onset of hepatic encephalopathy (neurological impairment with hyperammonaemia). In cases with inappropriate diagnoses, the main diagnosis that caused the liver damage was considered in those cases in which there was secondary damage, where there was prior liver disease or in the absence of liver damage criteria. During the study period, acute liver failure or acute liver damage was diagnosed in 444 patients. The results of the descriptive analysis are shown in Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of the sample.

| Mean±SD | |

| Age (years) | 53.8±17.25 |

| Value (%) | |

| Gender (male) | 209 (47.1) |

| Deceased | 190 (42.8) |

| Diagnoses considered appropriate | 55 (12.4) |

| Acute liver damage | 14 (3.2) |

| Severe acute liver damage | 22 (5.0) |

| Acute liver failure | 19 (4.3) |

| Diagnoses considered inappropriate | 389 (87.6) |

| Liver damage secondary to another process | |

| Sepsis/Septic shock | 122 (27.5) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 66 (14.9) |

| Cardiorespiratory arrest | 12 (2.7) |

| Post-transplant liver disease | 10 (2.3) |

| Pancreatitis | 9 (2) |

| Postoperative liver resection | 8 (1.8) |

| Haemorrhagic shock | 4 (0.9) |

| Liver trauma | 4 (0.9) |

| HELLP syndrome | 4 (0.9) |

| Intra-abdominal hypertension | 3 (0.7) |

| Near-drowning | 3 (0.7) |

| Aortic dissection | 3 (0.7) |

| Neurogenic shock | 3 (0.7) |

| Polytrauma | 2 (0.5) |

| Major burns | 2 (0.5) |

| Acute adrenal insufficiency | 2 (0.5) |

| Endocarditis with septic embolism | 2 (0.5) |

| Electrocution | 2 (0.5) |

| Anaphylactic shock | 2 (0.5) |

| Other causes | 36 (8.1) |

| Diagnosis of prior liver disease | 57 (12.8) |

| Acute hepatitis with no acute liver damage criteria (no coagulopathy) | 33 (7.4) |

SD: standard deviation.

Although other authors have already observed the inappropriate use of this term in a variety of situations,2 no studies have been conducted to date to quantify the current extent of this misuse. The findings of this study highlight the fact that this is not an isolated problem. The primary reason for the inappropriate use of these terms in our hospital is the onset of true liver damage secondary to another primary cause that gives rise to shock or multiple organ failure. We believe that there are two fundamental explanations for this finding: a lack of specific terminology in these situations and of consideration that these diagnoses may be the prior cause of acute liver failure, particularly in critical patients.1,4 Use of these terms in connection with liver transplant was only found in a small number of cases, probably due to the use of more specific terminology. A significant percentage of diagnoses (12.8%) concerned patients with prior liver disease, despite the fact that the very definition of acute liver failure excludes this comorbidity,1–3 even going back to its original description.5 Finally, another diagnosis deemed to be inappropriate was the finding of acute hepatitis with no signs of acute liver damage. The lack of a clear cut-off point to define the presence of coagulopathy may be an influential factor in this scenario.

The primary limitations of our study stem from its retrospective nature at a single site. The diagnoses were established by the doctors responsible for each patient, which implies a degree of variability between the healthcare professionals involved, and the recommended terms were taken from guidelines published after the study period. In addition, the low incidence of this entity could be related to a possible overestimation of inappropriate diagnoses, due to the higher incidence of the other scenarios. Finally, because the objective of the study was to identify those situations in which use of the terminology was not considered appropriate due to other processes, the correct use of the diagnostic term ‘acute liver damage’ was not analysed.

In conclusion, the terms ‘acute liver damage’ and ‘acute liver failure’ are excessively and inappropriately used in many different situations. Understanding the current use of these terms is vital in order to prevent this situation in the future.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Peñasco Y, Sánchez-Arguiano MJ, Jiménez-Alfonso AF, Campos-Fernández S, González-Castro A, Rodríguez-Borregán JC. Utilización no apropiada del término de insuficiencia hepática aguda en un hospital de tercer nivel. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:252–253.