Colonoscopy is used for the diagnosis and prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC), which is one of the biggest contributors to cancer-related death in Spain.1 The various endoscopy societies of have drafted clinical recommendations and guidelines to guarantee the quality of these examinations.2,3 In this regard, the guidelines specify two key quality indicators for colonoscopy: the adenoma detection rate (ADR) and the caecal intubation rate (CIR). An overall adenoma detection rate ≥25% (≥30% in males and ≥20% in females) is considered acceptable in CRC screening colonoscopies.3 However, in examinations performed following a positive faecal occult blood test (FOB+), acceptable rates are much higher: ≥40%.4

An acceptable CIR is ≥95% in screening colonoscopies and ≥90% for all other examinations.3,5

To facilitate the ADR calculation, increase the number of examinations included and prevent confusion, some authors have recently recommended also taking into account colonoscopies performed after a polypectomy or a CRC surgical procedure (known as follow-up colonoscopy), as well as all other colonoscopies (diagnostic colonoscopies), in addition to screening colonoscopies.5,6 Acceptable guideline figures for these two further types of colonoscopy have been published.5

To find out whether we met the quality standards, we decided to study the ADR and CIR in our examinations.

We retrospectively reviewed all the colonoscopies performed on patients over the age of 18 years at our Endoscopy Unit over a two-year period: from June 2014 (introduction of CRC screening endoscopies at our hospital) to June 2016. These examinations were divided into three groups: (1) screening colonoscopies, following a positive immunological faecal occult blood test; (2) follow-up colonoscopies after colon adenoma resection or curative CRC surgical procedure, and (3) diagnostic colonoscopies, which included all other examinations.

The procedures were performed by 12 endoscopists.

Any examinations performed by endoscopists who had performed fewer than 100 examinations in the study period were excluded. Incomplete or emergency colonoscopies or colonoscopies conducted without sufficient preparation, examinations performed to monitor and follow-up inflammatory bowel disease or hereditary polyposis syndromes, and any examinations that specifically did not require caecali intubation (e.g. endoscopic tattooing, follow-up of prior polypectomies, prosthesis placement, etc.) were also discounted.

The following definitions were used: ADR: percentage of colonoscopies with a finding of at least one histologically confirmed adenoma/adenocarcinoma, and CIR: percentage of colonoscopies which reach the caecum, with a view and a photograph of the base of the caecum.

The study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee (PI 17–840).

We reviewed 8772 colonoscopies in total, 891 of which were excluded. As such, we studied 7881 procedures, all considered by the endoscopists to have been well/excellently prepared: 4080 (51.7%) male and 3801 (48.3%) female, mean age 64±13.7 years. The colonoscopies were performed under conscious sedation using midazolam/pethidine or propofol (at the discretion of the individual endoscopist) administered by a specialist nurse. The resected polyps were analysed by pathologists specialising in the histology of the gastrointestinal tract.

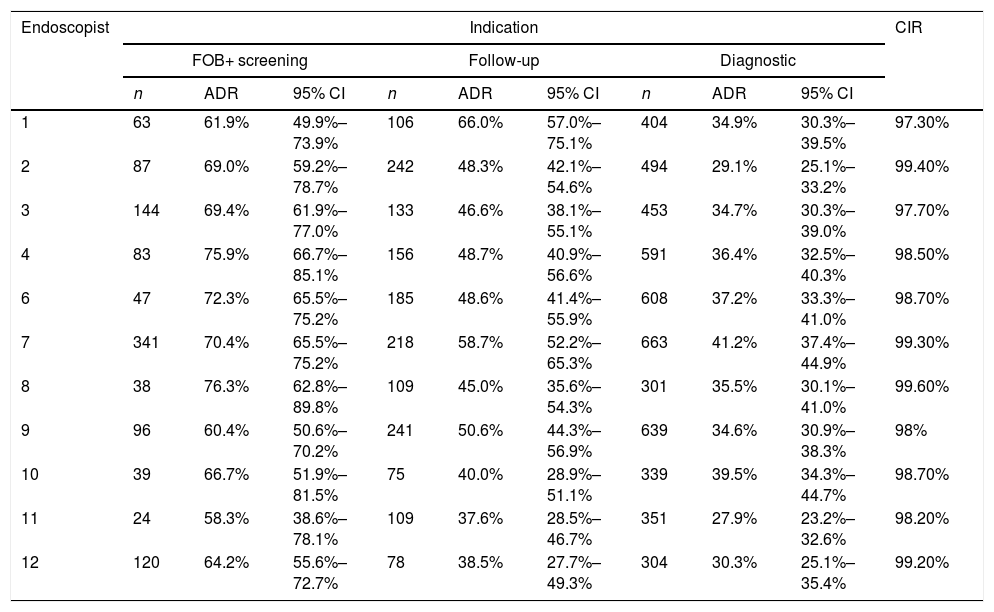

The results are shown in Table 1. Endoscopist 5 was removed from the study for failing to have conducted the required number of colonoscopies in the two years of the study. We found an overall ADR of 42.7% (50.6% ♂, 34.2% ♀). As expected, the highest ADRs were obtained in examinations performed following a FOB+ test, for which the percentages ranged from 58.3% for endoscopist 11 to 76.3% for endoscopist 9. The overall figure was 68.4% (78.4% ♂, 55.1% ♀). The ADRs obtained in follow-up colonoscopies after colorectal cancer surgery or after prior polypectomies were, as expected, higher than those obtained in endoscopies performed for other indications (e.g., abdominal pain, constipation, change in bowel habits, etc.). As such, the ADRs in follow-up colonoscopies ranged from 37.6% for endoscopist 11–66% for endoscopist 1, and an overall figure of 49.3% (53.9% ♂, 42.3% ♀). Finally, ADR percentages were lowest in the so-called diagnostic colonoscopies, ranging from 27.9% for endoscopist 11 to 41.2% for endoscopist 7, and an overall figure of 42.2% (50.6% ♂, 28.7% ♀). This is logical given that these examinations do not always adhere to the quality criteria in terms of the indication.

Adenoma detection rate and caecal intubation rate by endoscopist.

| Endoscopist | Indication | CIR | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOB+ screening | Follow-up | Diagnostic | ||||||||

| n | ADR | 95% CI | n | ADR | 95% CI | n | ADR | 95% CI | ||

| 1 | 63 | 61.9% | 49.9%–73.9% | 106 | 66.0% | 57.0%–75.1% | 404 | 34.9% | 30.3%–39.5% | 97.30% |

| 2 | 87 | 69.0% | 59.2%–78.7% | 242 | 48.3% | 42.1%–54.6% | 494 | 29.1% | 25.1%–33.2% | 99.40% |

| 3 | 144 | 69.4% | 61.9%–77.0% | 133 | 46.6% | 38.1%–55.1% | 453 | 34.7% | 30.3%–39.0% | 97.70% |

| 4 | 83 | 75.9% | 66.7%–85.1% | 156 | 48.7% | 40.9%–56.6% | 591 | 36.4% | 32.5%–40.3% | 98.50% |

| 6 | 47 | 72.3% | 65.5%–75.2% | 185 | 48.6% | 41.4%–55.9% | 608 | 37.2% | 33.3%–41.0% | 98.70% |

| 7 | 341 | 70.4% | 65.5%–75.2% | 218 | 58.7% | 52.2%–65.3% | 663 | 41.2% | 37.4%–44.9% | 99.30% |

| 8 | 38 | 76.3% | 62.8%–89.8% | 109 | 45.0% | 35.6%–54.3% | 301 | 35.5% | 30.1%–41.0% | 99.60% |

| 9 | 96 | 60.4% | 50.6%–70.2% | 241 | 50.6% | 44.3%–56.9% | 639 | 34.6% | 30.9%–38.3% | 98% |

| 10 | 39 | 66.7% | 51.9%–81.5% | 75 | 40.0% | 28.9%–51.1% | 339 | 39.5% | 34.3%–44.7% | 98.70% |

| 11 | 24 | 58.3% | 38.6%–78.1% | 109 | 37.6% | 28.5%–46.7% | 351 | 27.9% | 23.2%–32.6% | 98.20% |

| 12 | 120 | 64.2% | 55.6%–72.7% | 78 | 38.5% | 27.7%–49.3% | 304 | 30.3% | 25.1%–35.4% | 99.20% |

The CIRs were very similar for all endoscopists. The overall rate obtained was 98.6%, although we did not study these figures for every indication.

With the exception of endoscopist 7, who was specifically contracted to perform FOB+ screening colonoscopies, we found no statistically significant differences between the endoscopist's experience and the mean adenoma detection rate per colonoscopy for each endoscopist overall. On average, endoscopists with <5 years’ experience resected one adenoma per colonoscopy performed; those with 5–10 years’ experience 0.92; and senior endoscopists with >10 years’ experience removed 0.96 adenomas per colonoscopy (p=367).

As additional data but not included in the table or compared with the ADR, we sometimes used our polyp detection rate (PDR), which is much easier to obtain as no histological study is required, as a surrogate ADR marker.7 This parameter also revealed some good and interesting data: PDR of 41–91% for screening colonoscopies, 44–79% for follow-up colonoscopies and 23–56% for diagnostic colonoscopies.

These results are very satisfactory; the good ADR and CIR figures are surrogate markers of a thorough and comprehensive examination of the colonic mucosa. It can therefore be concluded that our colonoscopies are of good quality. As recommended in the clinical practice guidelines,8 the figures obtained adhere to the quality standards for FOB+ screening colonoscopies that are considered acceptable (>40%).

Unlike what is reported in the American literature,5 in our Unit there was very little variability in ADR percentage from one endoscopist to another, irrespective of their experience or their training background. This homogeneity can probably be attributed to the regulated, standardised and compulsory training provided through the MIR [Medical Intern] system in Spain (unlike the system used in the USA, where “board-certified and non-board-certified specialists” practice). In addition, the continuing medical education provided by scientific societies (AEG (Asociación Española de Gastroenterología [Spanish Gastroenterology Association]), SEED (Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva [Spanish Society of Digestive Endoscopy]), SEPD (Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva [Spanish Society of Digestive Pathology])), with a growing and consistent interest in increasing endoscopy quality parameters, undoubtedly also plays a key role.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, some important colonoscopy quality aspects, like the endoscope withdrawal time, were not collected. This would probably be of interest to include in future studies. Secondly, complications associated with the procedures were not recorded.

Finally, it is not possible to extrapolate the conclusions of this single-centre study to other centres. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to obtain these data from other Endoscopy Units to gain an overview and compare these figures across the country.

The authors would like to thank Dr María Pellisé for her help resolving our queries prior to initiating the study.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Rebollo ML, Alcaide-Suárez N, Burgueño-Gómez B, Antolin-Melero B, Muñoz-Moreno MF, Alonso-Martín C, et al. Tasa de detección de adenomas e intubación cecal: indicadores de calidad de la colonoscopia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:253–255.