Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver is a relatively rare disease of uncertain aetiology, characterised by chronic infiltration of inflammatory cells and fibrosis.1 It is also known as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour or plasma cell granuloma.1,2 It occurs most commonly in the lung, but can be found in other locations, including the spinal cord, eyes, spleen, lymph nodes, soft tissue and liver.1 Inflammatory pseudotumour of the liver accounts for 8% of extrapulmonary inflammatory pseudotumours.1 The aetiology and pathogenesis remain unknown, although chronic obstruction and stasis seem to be important aetiological factors. It is generally considered a non-neoplastic reactive inflammatory condition.2 Other causes postulated include infectious and autoimmune aetiology.1–3 Most patients present fever and abdominal pain.3,4 Inflammatory pseudotumours often present as large, solitary masses, predominantly in the right lobe, although multicentricity has also been described.1 Computed tomography (TC) usually reveals lesions with variable contrast enhancement, and they can present with a hypovascular character.4 On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), they appear hypointense on T1-weighted sequences, and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences.2,4 The clinical manifestations and imaging findings are similar to those of a malignant tumour, particularly cholangiocarcinoma, metastasis or hepatocarcinoma,1 except for the benign biological behaviour and spontaneous regression that have been described after conservative treatment with antibiotics or non-specific anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID).4,5 They should also be differentiated from cystic lesions, such as liver abscesses, which show incomplete liquefaction and granulation.1 When inflammatory pseudotumour is suspected, the importance of percutaneous large-core needle biopsy for diagnosis has been underscored.4 The treatment protocol for these pseudotumours continues to be controversial; surgical resection should be considered when there is no improvement or diagnostic uncertainty.4,6

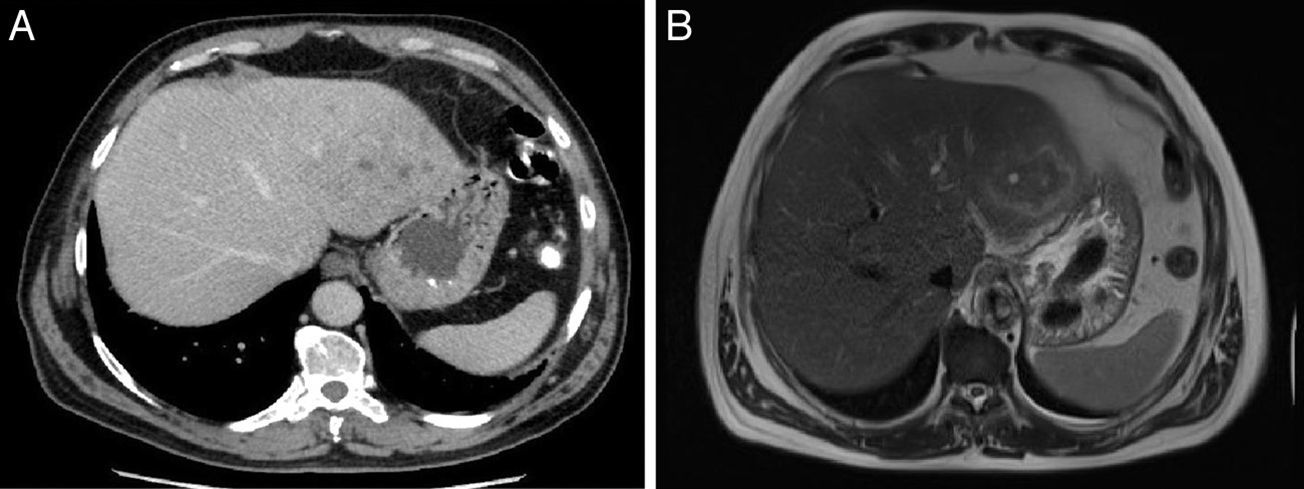

We present the case of a 57-year-old man with a history of high blood pressure, ischaemic heart disease revascularised with 2 stents and hypercholesterolaemia, who was admitted for a 2-month history of weight loss, intermittent fever, profuse night sweats and episodes of abdominal pain. Physical examination was unremarkable apart from hepatomegaly. Laboratory findings revealed leukocytosis (14,200cells/ml), moderate anaemia (haemoglobin 10.7g/dL), dissociated cholestasis (alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 212U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 288U/L)) and elevated acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 99mm/h, C-reactive protein (CRP) 136.9mg/dL). Tumour markers (alpha fetoprotein [AFP], carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA] and CA 19.9) were normal, and virus serology for Epstein–Barr virus, Coxiella, Borrelia, Rickettsia and hepatitis A, B and C were negative. The study was completed with abdominal CT, in which an 8-cm heterogeneous focal lesion was identified in the left lobe of the liver (Fig. 1a), with portal branch thrombosis and lymphadenopathies. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the lesion showed loss of signal in late phases, while on MRI, the lesion was identified as isointense on T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 1b), and discretely hypointense on T1-weighted sequences, with areas with a cystic–necrotic appearance and perilesional oedema, with homogeneous uptake after contrast administration. This suggested a lesion of an inflammatory nature, although a tumour origin could not be ruled out.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography (CT). An 8-cm hepatic lesion in segments II and III, of heterogeneous density, with confluent areas of lower density inside. (B) MRI scan of the liver. T2-weighted image, in which an isointense lesion can be observed in segments II and III, with areas with a cystic–necrotic appearance inside and perilesional oedema.

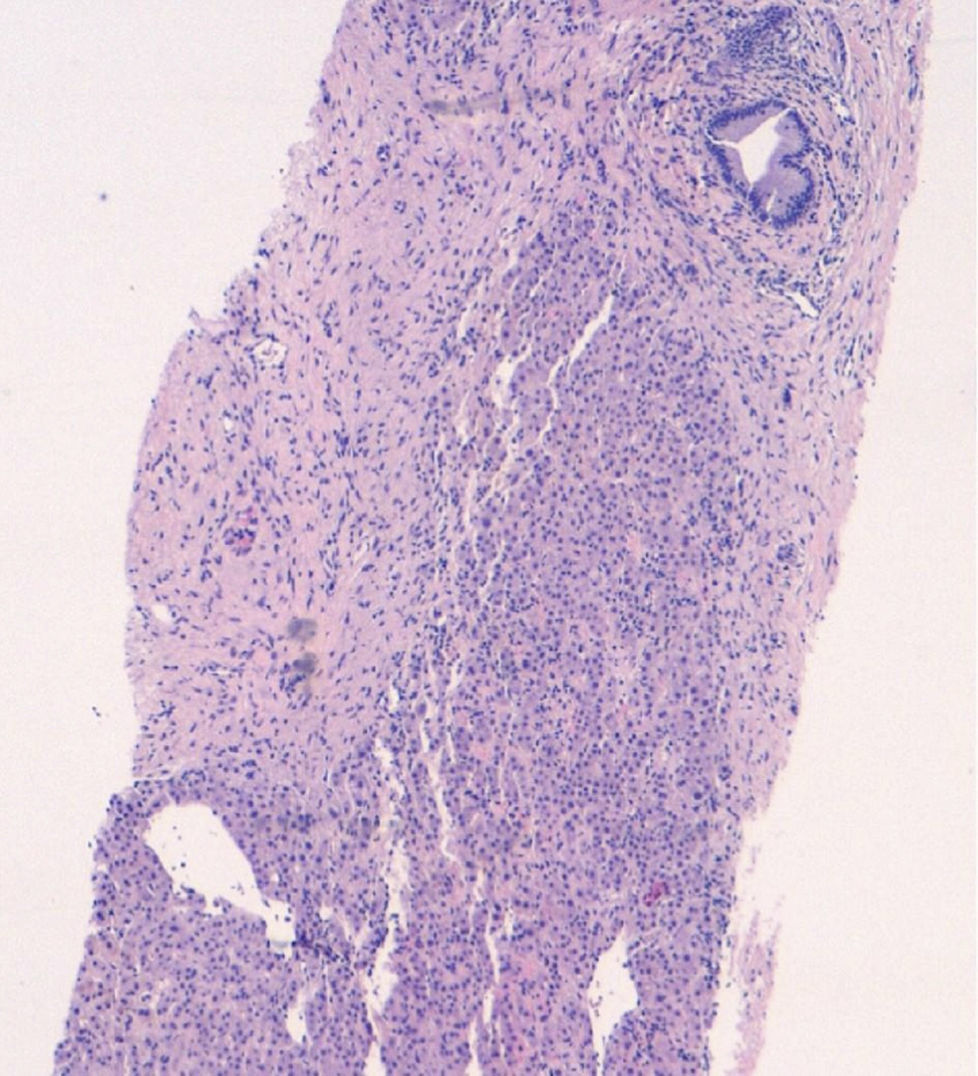

In view of these findings, CT-guided large-core needle biopsy was performed, with a histopathology diagnosis suggestive of inflammatory pseudotumour (Fig. 2), with vimentin+, AML+, desmin−, CD68− and ALK−, with no light chain restriction and a low proliferative index (15%).

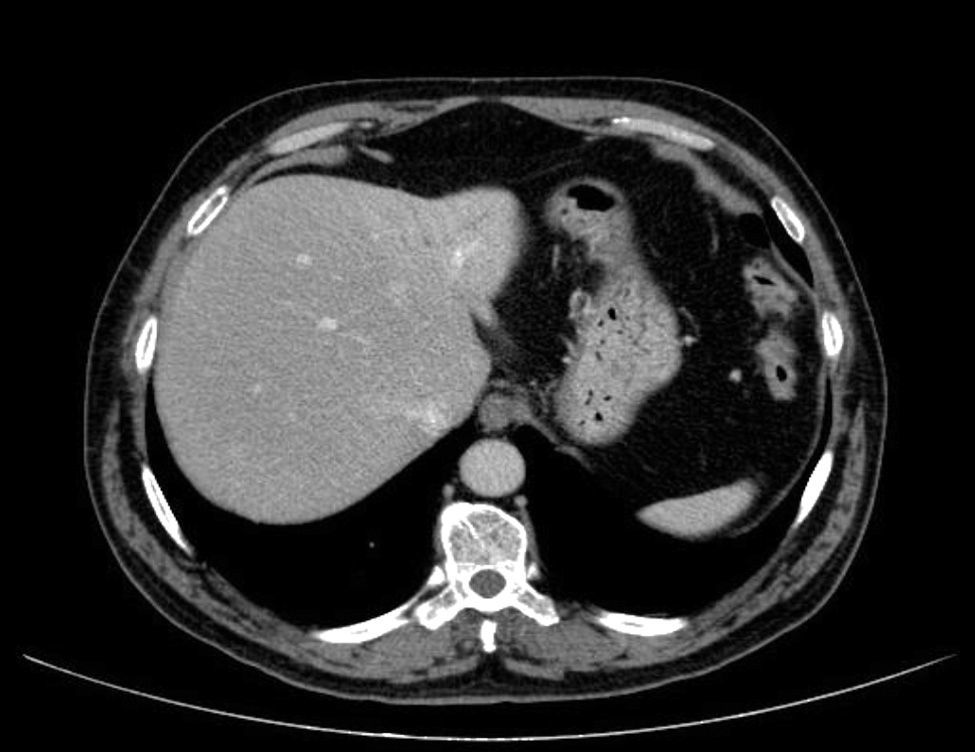

Conservative treatment with antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1000/62.5mg, 2 tablets every 12h) and follow-up was prescribed. The patient progressed well, with normalisation of the cholestasis and correction of the anaemia. One month later, the CT showed a 50% reduction in the lesion, and at 6 months it had almost disappeared; the patient remains asymptomatic (Fig. 3).

CT and MRI are the key to diagnosis in patients with liver masses and normal tumour markers, although due to the lack of pathognomonic findings, clinical suspicion and histological diagnosis are required for an accurate diagnosis.1 Inflammatory pseudotumours of the liver have a good prognosis with conservative treatment. Active histological diagnosis with large-core needle biopsy is guaranteed, but unnecessary surgical procedures should be avoided due to the possibility of spontaneous regression.1,4 The co-existence of malignancy cannot always be ruled out, so the routine use of large-core needle biopsy, due to the potential risks, is not recommended if there is high suspicion of malignancy.4 Bleeding, needle tract seeding and secondary infections have been described.4,6 Surgical resection is considered necessary when the symptoms continue despite medical treatment, the lesion increases in size, the tumour compresses vital structures, there are risk factors or there is diagnostic uncertainty.6 Hepatectomy minimises the risk of biopsy-related complications, and can provide better long-term outcomes.2

FundingThe authors declare that they have not received any funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Guerrero Puente L, Muñoz García-Borruel M, Barrera Baena P, de la Mata García M. Seudotumor inflamatorio hepático: a propósito de un caso. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:329–331.

![Liver at low magnification with the presence of fibrotic areas that have replaced the hepatic parenchyma and inflammatory foci (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E], 8×). Liver at low magnification with the presence of fibrotic areas that have replaced the hepatic parenchyma and inflammatory foci (haematoxylin and eosin [H&E], 8×).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/24443824/0000003900000005/v3_201605230804/S2444382416300104/v3_201605230804/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)