To determine the prevalence of endoscopic lesions unrelated with portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis.

Patients and methodsCross-sectional study including a consecutive cohort of patients with liver cirrhosis enrolled in a screening program of oesophageal varices who underwent an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy from November, 2013, to November, 2018. Clinical predictors of endoscopic lesions unrelated to portal hypertension were analyzed by univariate and multivariate logistic regression.

ResultsA total of 379 patients were included. The most frequent aetiology of liver disease was alcohol consumption (60.4%). The prevalence of endoscopic lesions unrelated with portal hypertension was 39.6% (n=150). Among 96 patients with peptic lesions, urease was obtained in 56.2% of patients (positive in 44.4% of them). The prevalence of endoscopic lesions unrelated to portal hypertension was not associated with age, gender, liver function or ultrasound findings of portal hypertension. Smokers had a trend to increased prevalence of endoscopic lesions unrelated to portal hypertension (43.2% vs 34.6%; p=0.09), particularly peptic ulcer (6.4% vs 0.6%; p=0.05) and peptic duodenitis (17.3% vs 6.3%; p=0.002). Active smoking was the only independent predictor of peptic ulcer or duodenitis (OR=2.56; p=0.017).

ConclusionActive smoking is a risk factor for endoscopic lesions unrelated to portal hypertension. This finding should be further investigated to reassess endoscopic screening programs in cirrhotic smokers.

El consenso de Baveno VI para el cribado endoscópico de varices esofágicas en algunos pacientes. Bajo esta estrategia, podrían pasar desapercibidas lesiones no relacionadas con hipertensión portal, algunas de ellas potencialmente graves. El objetivo de este estudio es determinar la prevalencia de dichas lesiones e identificar los factores clínicos asociados a las mismas.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio transversal unicéntrico sobre una cohorte consecutiva de pacientes cirróticos sometidos a endoscopia digestiva alta en el contexto de un programa de cribado de varices esofagogástricas entre noviembre de 2013 y noviembre de 2018. Se analizaron factores de riesgo para la presencia de lesiones no relacionadas con hipertensión portal mediante regresión logística uni- y multivariante.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 379 pacientes. La etiología mayoritaria de la cirrosis fue etílica (n=229; 60,4%). La prevalencia de lesiones endoscópicas no relacionadas con hipertensión portal fue del 39,6% (n=150). Entre los 96 pacientes con patología péptica (25,3%) se tomó test de ureasa en 54 (56,2%), siendo positiva en 24 (44,4%). La presencia de lesiones endoscópicas no relacionadas con hipertensión portal no estuvo influida por la edad (p=1), el género (p=0,28), la función hepática (MELD p=0,20, Child-Pugh p=0,77) o la presencia de datos ecográficos de hipertensión portal (p=0,14). Los pacientes fumadores presentaron tendencia a mayor prevalencia de lesiones endoscópicas no relacionadas con la hipertensión portal (43,2% vs 34,6%; p=0,09), particularmente úlcera péptica (6,4% vs 0,6%; p=0,05) y duodenitis péptica (17,3% vs 6,3%; p=0,002). El tabaquismo activo fue el único factor predictivo independiente de ulcus o duodenitis péptica (OR=2,56; IC95% 1,18–5,56; p=0,017).

ConclusionesEl tabaquismo activo aumenta el riesgo de lesiones endoscópicas no relacionadas con hipertensión portal, lo cual debería ser investigado en profundidad para redefinir el cribado endoscópico en pacientes fumadores con cirrosis hepática.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) of variceal origin is one of the main complications derived from portal hypertension (PHT) in patients with liver cirrhosis, contributing substantially to increased mortality. The clinical practice guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)1 and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)2 recommend upper gastrointestinal tract (UGI) endoscopy for the screening of gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. The Baveno VI3 recommendations suggested adhering to cost-effectiveness criteria, and establish that endoscopic screening could be avoided in patients with liver elastography <20kPa and a platelet count >150×103. However, 30%–40% of episodes of UGIB in patients with cirrhosis are due to non-PHT-related lesions, with peptic ulcer (PU) accounting for 10% of cases.4 Data on the prevalence of these lesions are scant and come from urgent endoscopic series for UGIB1,5, which constitutes a selection bias and renders it impossible to ascertain the actual prevalence. This information would be highly relevant, since the early treatment of these lesions makes it possible to prevent serious complications and hospitalisations.6

The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions in patients with cirrhosis and to identify the clinical factors associated with them.

Patients and methodsDesign and ethical considerationsA cross-sectional study was performed on a consecutive cohort of patients with liver cirrhosis, treated by UGI endoscopy as part of a gastroesophageal varices screening programme over a five-year period (November 2013-November 2018). Patients aged under 18 years were excluded, as were cases of PHT on non-cirrhotic liver. The patients were selected from the 'Pacientes' [Patients] electronic registry, which includes the endoscopies performed at our centre encoded and updated in real time. These procedures were performed by a group of 10 endoscopists in our unit's endoscopy room. Olympus® (EXERA III CF-HQ190) endoscopes and conscious sedation with intravenous midazolam were used. The examinations performed on patients with no gastrointestinal symptoms were selected, with the indication encoded as [(varices screening) or (varices control)] and ['cirrhosis' or 'chronic liver disease']. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the data were processed anonymously as provided for by Spanish Organic Law on Data Protection 3/2018 and European Regulation 2016/679. The informed consent of the patients or their relatives was obtained for the performance of the UGI endoscopy. Since it is a retrospective study, the patients were not provided with a specific informed consent form to participate in the study, which was approved by the local ethics committee (1507-N-20).

Data extraction, definitions and study variablesThe data required for the study were obtained by three independent investigators (ASL, MRT and AAS) from the patients' digital medical record. The study's primary endpoint was the existence of non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions, including: oesophagitis, hiatal hernia, gastritis (except for PHT-related congestive gastritis), peptic ulcer, gastric erosions and cancerous or pre-cancerous lesions. Sampling information was collected, both for biopsy and for the determination of Helicobacter pylori (HP) by urease test (Clotest®, Avanos Medical Sales).

The following variables were analysed: age, gender, patient origin (outpatient/inpatient), nature of the endoscopy (elective/early), time of the endoscopy (first/control endoscopy), endoscopy findings, smoking history, the taking of antiplatelet drugs, anti-inflammatories or proton pump inhibitors (PPI), the aetiology of liver cirrhosis, liver function (Child-Pugh and MELD score), findings on the latest ultrasound (splenomegaly, ascites, hepatocarcinoma, portal thrombosis), gastroesophageal varices and PHT gastropathy.

Ultrasound PHT was defined as the presence of ascites, portosystemic shunt or splenomegaly on the most recent ultrasound prior to the performance of the UGI endoscopy.

Calculation of the sample sizeThe sample size required for the study was calculated using the EPIDAT v3.1 program (Xunta de Galicia/HDA [PAHO - WHO]). The working hypothesis was that a given patient risk profile or factor would be associated with a greater risk of non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions. The following assumptions were made:

–Prevalence of the risk factor or profile: 30%.

–Prevalence of endoscopic lesions in patients with the risk factor or profile: 25%.

–Prevalence of endoscopic lesions in patients without the risk factor or profile: 10%.

–Statistical power: 80%.

–Alpha error: 5%.

–Incomplete data or missing values: 10%.

The minimal sample size required was 325 patients. In total, 379 patients were ultimately included in the study.

Statistical analysisThe qualitative variables were expressed by absolute number of patients and as a percentage. The quantitative variables were described by the mean±standard deviation, except in variables with asymmetrical distribution, in which case the median and interquartile range were used. Appropriate statistical hypothesis tests were used according to the type of variables analysed. A multivariate analysis was performed by means of multiple logistic regression in order to identify variables independently associated with the presence of non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions, as well as to control possible confounding factors. All the statistical hypothesis tests were bilateral and the value of p<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. The statistical study was performed using the SPSS® Statistics.v.19 (Armonk, NY, USA) statistics package.

ResultsBaseline characteristicsIn total, 78.8% of the 379 patients included were male, with a mean age of 57.5±11.4 years. The most common aetiology of cirrhosis was alcoholic (60.4%), followed by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) (26.9%). Other aetiologies were: hepatitis B virus (HBV) (12.4%), metabolic hepatic steatosis (9%), cryptogenic cirrhosis (7.1%), autoimmune hepatitis (1.6%), primary sclerosing cholangitis (1.1%) and primary biliary cholangitis (0.5%). Overall, 58% of the patients were smokers or former smokers. 15.3% were taking aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 13.2% beta-blockers and 35.9% PPI. Liver function was preserved in the majority, with a mean Child-Pugh score of 6.8±2.1 and a MELD of 11.7±5. In total, 42.7% (n=162) had a Child-Pugh B-C liver function score and 29.6% (n=112) a MELD score >14. 33.7% had manifested some previous decompensation, most commonly ascites (39.6%; n=150). 71.8% had ultrasound PHT data. The main patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Patient clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics | General | Non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence | Absence | |||

| Female gender (%) | 22.2% | 34.5% | 65.5% | 0.28 |

| Age (years) | 57.5±11.4 | 57.5±11.4 | 57.5 | 1 |

| Alcoholic aetiology, n (%) | 229 (60.4) | 90 (39.3) | 139 (60.7) | 0.36 |

| HCV aetiology, n (%) | 102 (26.9) | 40 (39.2) | 62 (68.2) | 0.67 |

| Child-Pugh | 6.8±2.1 | 6.9±2.2 | 6.8±2 | 0.77 |

| MELD | 11.7±5 | 11.3±5.1 | 12±4.9 | 0.20 |

| Ultrasound PHT data, n (%) | 272 (71.8) | 114 (41.9) | 158 (58.1) | 0.14 |

| Smokers or former smokers, n (%) | 220 (58) | 95 (43.2) | 125 (56.8) | 0.06 |

| Previous decompensations, n (%) | 124 (32.7) | 41 (33.1) | 83 (66.9) | 0.22 |

Association between the presence of non-portal hypertension-related endoscopic lesions and the patients' clinical characteristics.

In total, 61.2% of the patients (n=232) had oesophageal varices at screening, 59.1% of which were large. Findings consistent with PHT gastropathy were found in 53.3% of the patients, 4.5% of which were serious.

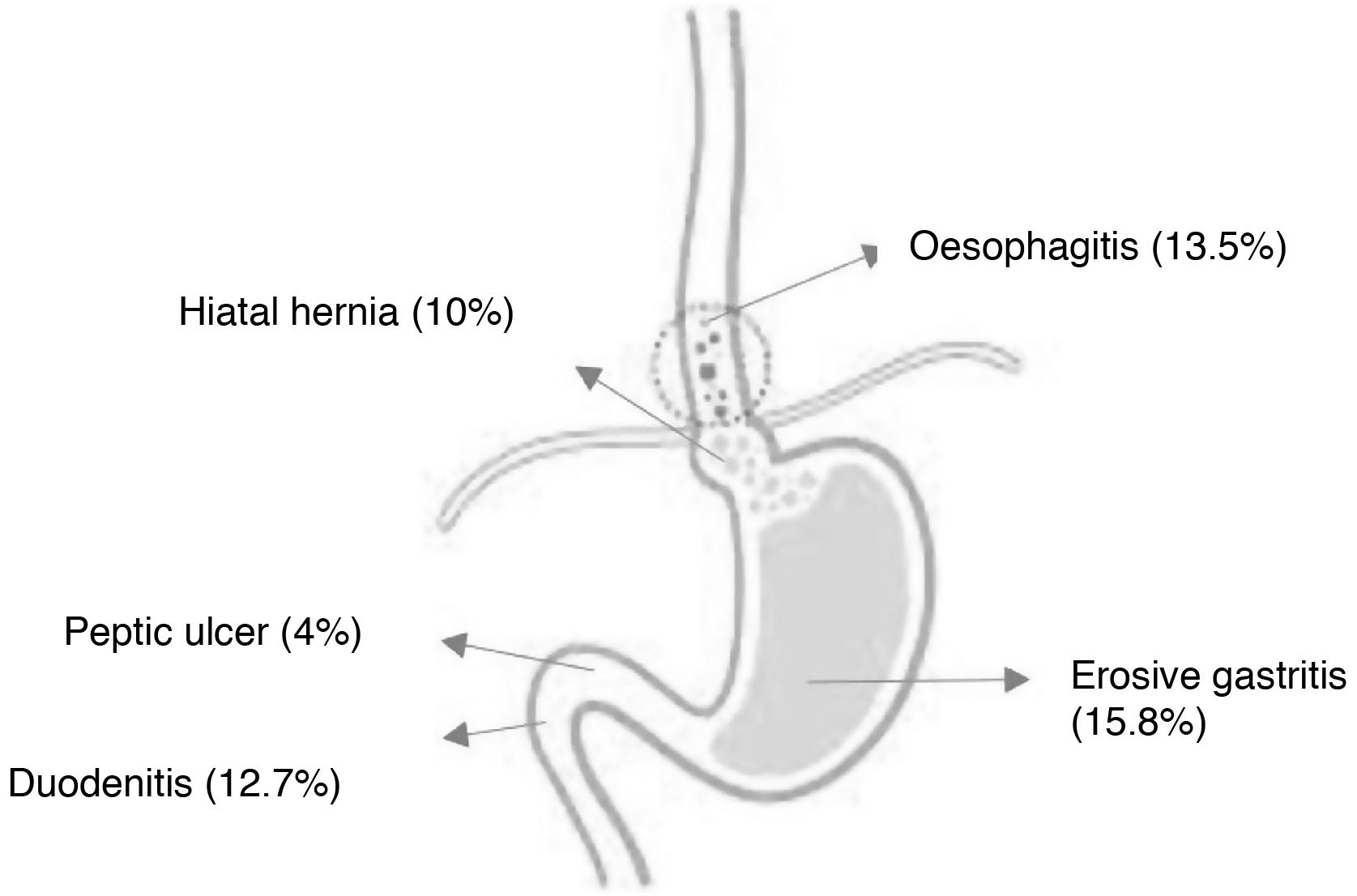

The prevalence of non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions was 39.6% (n=150): 15.8% erosive gastritis, 13.5% oesophagitis, 12.7% duodenitis, 10% hiatal hernia and 4% PU (Fig. 1). Peptic disease was identified in 96 patients (25.3%) (erosive gastritis, duodenitis or ulcer), with a urease test performed in 54 (56.2%). The result of the test was positive in 44% (n=24). The taking of the urease test is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Factors related to non-portal hypertension-related endoscopic lesionsThe prevalence of non-PHT-related lesions was not affected by age (57.5±11.4 years vs 57.5±11.4 years; p=1), gender (19.3% vs 80.7%; p=0.28), liver function (MELD [11.7 vs 11.9; p=0.71], Child-Pugh [6.8 vs 6.9; p=0.54]), the presence of ultrasound PHT (24% vs 76%; p=0.14) or HCV cirrhosis (72.7% vs 27.3%; p=0.88). Smokers showed a tendency for greater prevalence of these lesions (43.2% vs 34.6%; p=0.09). Alcoholic cirrhosis and smoking showed a certain synergistic effect in the development of non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions (57.3% with the two factors, 32.7% with one of the two factors and 10% with none), although statistical significance was not reached (Fig. 3).

With regard to the predictive factors for the development of more clinically relevant lesions, smokers exhibited a greater prevalence of PU (6.4% vs 0.6%; p=0.05) and peptic duodenitis (17.3% vs 6.3%; p=0.002). In the multivariate analysis that evaluated the predictors of PU or peptic duodenitis, being an active smoker was the only independent predictive factor (odds ratio=2.56; 95% confidence interval: 1.18–5.56; p=0.017) after controlling for possible confounding factors, including: age, gender, alcoholic cirrhosis, previous decompensations, taking aspirin, NSAID derivatives and PPI (Table 2).

Multiple logistic regression.

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active smoker | 2.56 | 1.18−5.56 | 0.017 |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.95−1.01 | 0.18 |

| Gender (male) | 2.59 | 0.85−7.85 | 0.09 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 0.88 | 0.38−2.07 | 0.78 |

| Previous decompensations | 0.75 | 0.35−1.63 | 0.48 |

| ASA/NSAIDs | 2.06 | 0.86−4.93 | 0.10 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 0.76 | 0.36−1.63 | 0.48 |

Evaluation of independent predictive factors of peptic ulcer or duodenitis in upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy.

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CI, confidence interval; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OR, odds ratio.

This study shows that approximately one in every three patients with liver cirrhosis has non-PHT-related lesions. The prevalence of lesions is higher in patients who are smokers, particularly in those with alcoholic liver disease. For this reason, we consider that in this group of patients, endoscopic screening beyond that which is recommended by Baveno VI could be considered in order to detect non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions.

This study is one of the largest conducted to date and considers both peptic disease and other upper GI tract lesions.7 Most of the available evidence comes from studies performed in symptomatic patients, particularly with suspected UGIB,8 which represents a high risk of selection bias. This explains a prevalence of PU in our study below that which has been observed in other publications,9 albeit similar to and even greater than that described in previous studies that also considered asymptomatic cirrhotic patients or those with additional risk factors for PU.10,11 In cirrhotic patients with UGIB, it has been estimated that the bleeding is due to a non-PHT-related endoscopic lesion in 30%–40% of cases.4 Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al.12 reported that the origin of bleeding in half of the patients was gastroduodenal ulcers. Moreover, short-term mortality for non-PHT-related lesions may be similar to that caused by variceal bleeding.13,14

Studies from 200515 showed relatively low use of NSAIDs in patients with liver cirrhosis and bleeding caused by gastroduodenal peptic ulcer disease, which translates into a lower influence than in the general population (42.8% vs 58.2%). Subsequent studies excluded patients treated with NSAIDs and antiplatelet drugs.9 Our study considered the administration of NSAIDs, aspirin and PPI, finding no relationship with peptic disease, similar to the findings of a French study that concluded that most haemorrhages were not related to NSAIDs or portal hypertension.16

The influence of portal hypertension in patients with liver cirrhosis is not clear.17 However, a meta-analysis from 200218 related it to the pathogenesis of gastroduodenal ulcer disease. The eradication of portal hypertension does not protect patients from ulcer recurrence.19 Similarly, Voulgaris et al.9 did not find it to be decisive in the pathogenesis of PU. In this study, the majority of patients who took urease tested positive, findings which are similar to those described by Kim et al. (44.4% vs. 35.1%).10 Despite the by no means negligible prevalence of peptic lesions in our study, the urease test was performed in just over half of the patients, probably on account of the endoscopist's reluctance to take samples, coagulopathy or because other PHT-related lesions were detected.

The most common aetiology of cirrhosis in our cohort was alcoholic, whereas in another recent similar study9 it was viral (37%). We found no differences in the prevalence of peptic disease according to the different aetiologies of cirrhosis, similar to that reported in previous studies (7,8,9), barring that of Siringo et al., which described a greater prevalence of PU in HBV.20 The prevalence of non-PHT-related lesions was also not impacted by the severity of the cirrhosis expressed by Child-Pugh and MELD or previous decompensations, which is consistent with most studies.9,21–23 However, other authors7 found that advanced stages of liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh C) were associated with a significantly greater prevalence of PU than the early stages (Child A), which was confirmed by Kim et al.10

It seems that patients with alcoholic cirrhosis have a greater prevalence of PU than the general population and than non-alcoholic cirrhosis patients.24,25 It is known that smoking prevalence is high in patients who drink to excess,26 and both of these factors predispose to peptic disease and cancer, such as hepatocarcinoma.26,27 No neoplastic disease was identified in the endoscopic screening of our sample. Although no association between smoking and PU has been established in the literature,7 Bang et al. describe a greater incidence of PU in smokers with chronic liver disease.28 Our cohort shows that patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, particularly smokers, tend to show a greater prevalence of peptic lesions, as well as other non-PHT-related lesions. Voulgaris et al.9 report that up to 25% of the patients who initially do not meet endoscopic screening criteria according to the Baveno VI criteria3 could exhibit peptic lesions on endoscopy. These data are supported by the findings in our cohort, with a significant prevalence of peptic disease in the subgroup of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis who are smokers, despite having preserved liver function. To date, the possible cost-effectiveness of endoscopic screening outside these criteria has not been analysed.

This study is limited by its cross-sectional design, which precludes the establishment of a temporal relationship between the risk factors and the emergence of endoscopic lesions. It has also not been possible to protocolise the description of lesions among the different endoscopists involved. The lack of elastography close to the performance of the endoscopy rendered it impossible to ascertain the proportion of patients who fulfilled the Baveno VI criteria at baseline. Moreover, since no reliable information is available about patients' alcohol consumption pattern at the time of endoscopy, it proved impossible to analyse its influence on the appearance of peptic-type lesions. Finally, the fact that this was a single-centre study could limit the extrapolation of findings to other cohorts with a different epidemiological context or treated by means of different follow-up protocols.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a high prevalence of non-PHT-related endoscopic lesions in cirrhotic patients treated as part of a variceal screening programme. If they had not been screened, these lesions could have gone unnoticed. Smokers, particularly if they have underlying alcoholic cirrhosis, evince a higher prevalence of peptic lesions. Prospective studies are required, ideally randomised, comparing different follow-up strategies to assess their cost-effectiveness, taking into account the prevalence of all endoscopic lesions and not just PHT-derived lesions.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the nurses and auxiliary staff of the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Unit for their work.

Please cite this article as: Santos Lucio A, Rodríguez Tirado I, Aparicio Serrano A, Jurado García J, Barrera Baena P, González Galilea Á, et al. Hallazgos endoscópicos no relacionados con hipertensión portal en pacientes con cirrosis hepática sometidos a un programa de cribado de varices, Gastroenterología y Hepatología. 2022;96:450–456.