Portal hypertension is a hemodynamic abnormality that complicates the course of cirrhosis, as well as other diseases that affect the portal venous circulation. The development of portal hypertension compromises prognosis, especially when it rises above a certain threshold known as clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH). In the consensus conference on Portal Hypertension promoted by the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver and the Hepatic and Digestive diseases area of the Biomedical Research Networking Center (CIBERehd), different aspects of the diagnosis and treatment of portal hypertension caused by cirrhosis or other diseases were discussed. The outcome of this discussion was a set of recommendations that achieved varying degrees of consensus among panelists and are reflected in this consensus document. The six areas under discussion were: the relevance of clinically significant portal hypertension and the non-invasive methods used for its diagnosis and that of cirrhosis, the prevention of the first episode of decompensation and its recurrence, the treatment of acute variceal bleeding and other complications of portal hypertension, the indications for the use of TIPS, and finally, the diagnosis and treatment of liver vascular diseases.

La hipertensión portal es una anomalía hemodinámica que complica el curso de la cirrosis, así como de otras enfermedades que afectan a la circulación venosa portal. El desarrollo de hipertensión portal grava negativamente el pronóstico, especialmente cuando asciende por encima de una determinada cuantía conocida como hipertensión portal clínicamente significativa (HPCS). En la conferencia de consenso en Hipertensión Portal promovida por la Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado y el área de enfermedades hepáticas y digestivas del Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red (CIBERehd) se han discutido diferentes aspectos del diagnóstico y tratamiento de la hipertensión portal causada por la cirrosis o por enfermedades diferentes a ésta. El resultado de esta discusión fue la redacción de un conjunto de recomendaciones que alcanzaron diferentes grados de consenso entre los panelistas y que se han plasmado en el presente documento de consenso. Las seis áreas objeto de la discusión han sido: la relevancia de la hipertensión portal clínicamente significativa y los métodos no invasivos utilizados para su diagnóstico y el de la cirrosis, la prevención del primer episodio de descompensación y de su recurrencia, el tratamiento de la hemorragia aguda por varices y de otras complicaciones de la hipertensión portal, las indicaciones del uso del TIPS y, por último, el diagnóstico y tratamiento de las enfermedades vasculares del hígado.

Portal hypertension is the most common and severe complication in patients with cirrhosis, occurring when the portal pressure gradient (PPG, pressure difference between the portal vein and the inferior vena cava) is greater than 5 mmHg. The hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) is an excellent surrogate marker of PPG which can be estimated in clinical practice by catheterisation of the suprahepatic veins. HVPG is calculated as the difference between wedged hepatic venous pressure (WHVP) and free hepatic venous pressure (FHVP). In cirrhosis, especially in cirrhosis of alcoholic or viral origin, WHVP faithfully reflects portal pressure.1 HVPG measurement is a simple, safe and minimally invasive procedure well tolerated by the patient, as it is not necessary to puncture the portal vein. In addition, measurement of HVPG may be useful in portal hypertension other than sinusoidal hypertension, as it can differentiate pre-hepatic/pre-sinusoidal portal hypertension from hepatic and post-hepatic portal hypertension, and can be complemented by transjugular liver biopsy or right heart catheterisation.2

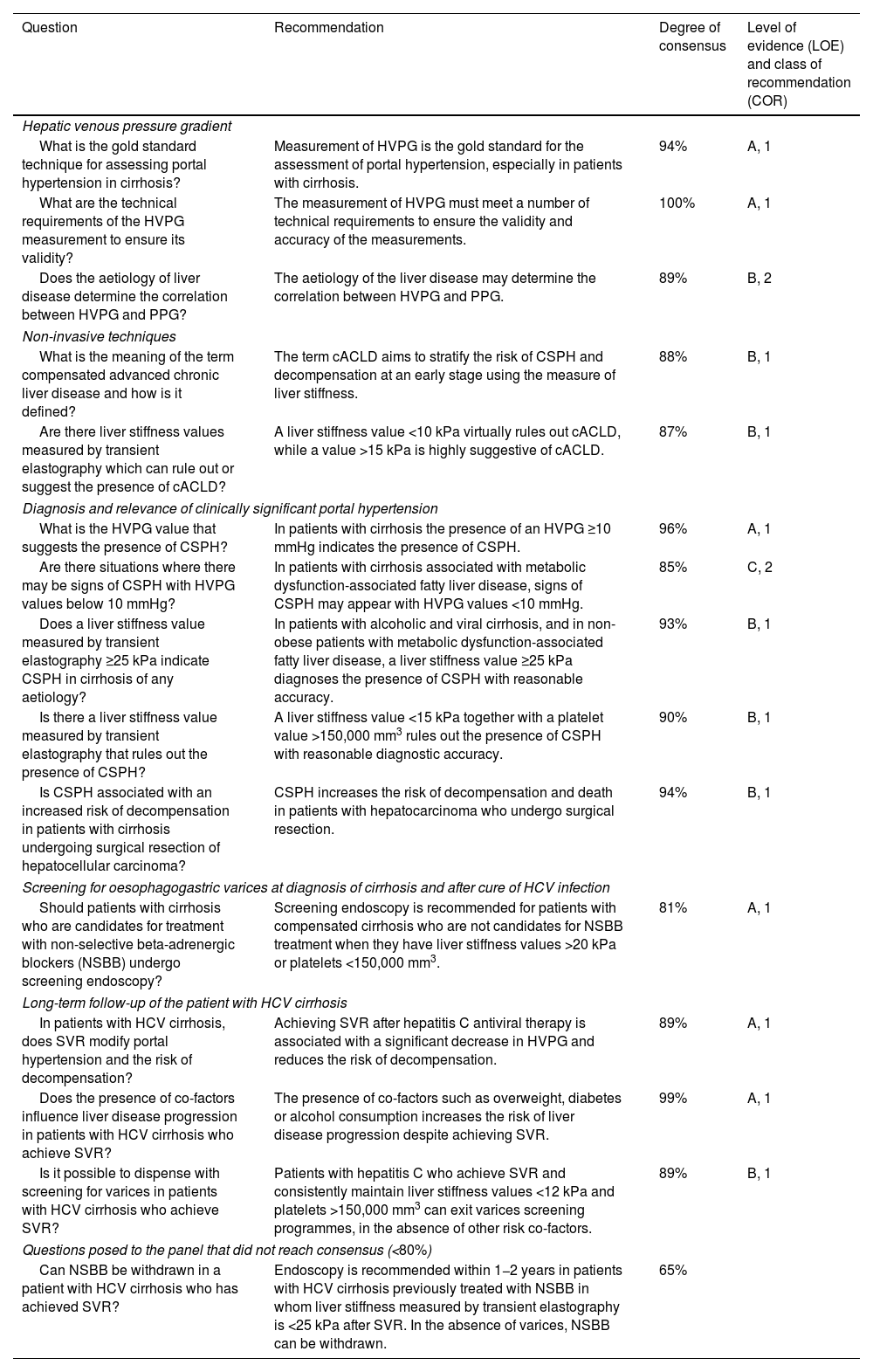

Recommendations on the diagnosis of cirrhosis and portal hypertension (session 1).

| Question | Recommendation | Degree of consensus | Level of evidence (LOE) and class of recommendation (COR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic venous pressure gradient | |||

| What is the gold standard technique for assessing portal hypertension in cirrhosis? | Measurement of HVPG is the gold standard for the assessment of portal hypertension, especially in patients with cirrhosis. | 94% | A, 1 |

| What are the technical requirements of the HVPG measurement to ensure its validity? | The measurement of HVPG must meet a number of technical requirements to ensure the validity and accuracy of the measurements. | 100% | A, 1 |

| Does the aetiology of liver disease determine the correlation between HVPG and PPG? | The aetiology of the liver disease may determine the correlation between HVPG and PPG. | 89% | B, 2 |

| Non-invasive techniques | |||

| What is the meaning of the term compensated advanced chronic liver disease and how is it defined? | The term cACLD aims to stratify the risk of CSPH and decompensation at an early stage using the measure of liver stiffness. | 88% | B, 1 |

| Are there liver stiffness values measured by transient elastography which can rule out or suggest the presence of cACLD? | A liver stiffness value <10 kPa virtually rules out cACLD, while a value >15 kPa is highly suggestive of cACLD. | 87% | B, 1 |

| Diagnosis and relevance of clinically significant portal hypertension | |||

| What is the HVPG value that suggests the presence of CSPH? | In patients with cirrhosis the presence of an HVPG ≥10 mmHg indicates the presence of CSPH. | 96% | A, 1 |

| Are there situations where there may be signs of CSPH with HVPG values below 10 mmHg? | In patients with cirrhosis associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, signs of CSPH may appear with HVPG values <10 mmHg. | 85% | C, 2 |

| Does a liver stiffness value measured by transient elastography ≥25 kPa indicate CSPH in cirrhosis of any aetiology? | In patients with alcoholic and viral cirrhosis, and in non-obese patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, a liver stiffness value ≥25 kPa diagnoses the presence of CSPH with reasonable accuracy. | 93% | B, 1 |

| Is there a liver stiffness value measured by transient elastography that rules out the presence of CSPH? | A liver stiffness value <15 kPa together with a platelet value >150,000 mm3 rules out the presence of CSPH with reasonable diagnostic accuracy. | 90% | B, 1 |

| Is CSPH associated with an increased risk of decompensation in patients with cirrhosis undergoing surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma? | CSPH increases the risk of decompensation and death in patients with hepatocarcinoma who undergo surgical resection. | 94% | B, 1 |

| Screening for oesophagogastric varices at diagnosis of cirrhosis and after cure of HCV infection | |||

| Should patients with cirrhosis who are candidates for treatment with non-selective beta-adrenergic blockers (NSBB) undergo screening endoscopy? | Screening endoscopy is recommended for patients with compensated cirrhosis who are not candidates for NSBB treatment when they have liver stiffness values >20 kPa or platelets <150,000 mm3. | 81% | A, 1 |

| Long-term follow-up of the patient with HCV cirrhosis | |||

| In patients with HCV cirrhosis, does SVR modify portal hypertension and the risk of decompensation? | Achieving SVR after hepatitis C antiviral therapy is associated with a significant decrease in HVPG and reduces the risk of decompensation. | 89% | A, 1 |

| Does the presence of co-factors influence liver disease progression in patients with HCV cirrhosis who achieve SVR? | The presence of co-factors such as overweight, diabetes or alcohol consumption increases the risk of liver disease progression despite achieving SVR. | 99% | A, 1 |

| Is it possible to dispense with screening for varices in patients with HCV cirrhosis who achieve SVR? | Patients with hepatitis C who achieve SVR and consistently maintain liver stiffness values <12 kPa and platelets >150,000 mm3 can exit varices screening programmes, in the absence of other risk co-factors. | 89% | B, 1 |

| Questions posed to the panel that did not reach consensus (<80%) | |||

| Can NSBB be withdrawn in a patient with HCV cirrhosis who has achieved SVR? | Endoscopy is recommended within 1−2 years in patients with HCV cirrhosis previously treated with NSBB in whom liver stiffness measured by transient elastography is <25 kPa after SVR. In the absence of varices, NSBB can be withdrawn. | 65% | |

cACLD: compensated advanced chronic liver disease; CSHP: clinically significant portal hypertension; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HVPG: hepatic venous pressure gradient; kPa: kilopascals; NSBB: nonselective beta-adrenergic blockers; PPG: portal pressure gradient; SVR: sustained viral response.

To ensure that the HVPG measurement is correct, it is important to standardise the technique so that the results are valid, accurate and reproducible.3 For this purpose, digital equipment that allows continuous tracings at low speed (maximum 7.5 mm/s) should be used to calculate the average pressure of a representative segment. For WHVP measurement, a catheter/balloon should be used to occlude a representative sinusoidal territory and a small amount of radiological contrast injected to confirm correct occlusion of the vein and to check for the presence of hepatic veno-venous communications as, if present, if they prevent correct occlusion of the suprahepatic vein, the HVPG value may be underestimated.4 To measure WHVP correctly, a stabilisation period of the trace is necessary, so it is recommended to record at least 1 min with a minimum of 20−30 s of stable trace. In addition, to ensure that the WHVP measurement is correct and reproducible, it should be determined in triplicate. FHVP should be measured in the suprahepatic vein 2−3 cm from the confluence with the inferior vena cava. Calculation of HVPG using the right atrial or inferior vena cava pressure value instead of FHVP is less accurate and should be avoided.5,6 The HVPG value may be underestimated if the measurement is performed under deep sedation, both because of the possible hypotensive effect of the drugs and their effect on respiratory dynamics modifying intra-abdominal pressure, and should therefore be avoided.7 Other factors such as haemodynamic instability, treatment with vasoactive drugs, mechanical ventilation, polytransfusion or evacuative paracentesis with albumin replacement in the hours prior to the procedure may also alter the measurement of HVPG. Importantly, if the catheterisation technique and recording are performed correctly, the degree of both inter-observer and test-retest agreement is excellent.8,9

The aetiology of the liver disease may affect the correlation between HVPG and PPGWHVP accurately reflects portal pressure in cirrhosis of viral and alcoholic aetiology and the concordance between the PPG and HVPG is excellent in these aetiologies.10,11 In patients with cirrhosis due to fatty liver disease of metabolic origin, the concordance between the two gradients is likely to be lower. A recent study analysing the concordance of WHVP and directly measured portal pressure in patients with decompensated cirrhosis due to metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) showed that WHVP underestimates portal pressure in up to one third of the patients analysed.12 It is not known whether this discordance exists in the compensated phase of the disease. In patients with pre-sinusoidal or pre-hepatic hypertension, the WHVP measurement is not a true reflection of portal pressure as it measures pressure in the sinusoidal territory, but is not able to capture changes beyond the sinusoid. Finally, in patients with cirrhosis secondary to primary biliary cholangitis, there is a component of presinusoidal portal hypertension without necessarily cirrhosis and which is not reliably captured by HVPG.13,14

2. Non-invasive techniquesThe term compensated advanced chronic liver disease (cACLD) aims to stratify the risk of clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) and decompensation early using the measure of liver stiffnessThe widespread use in clinical practice of transient elastography to measure liver stiffness and estimate the severity of liver fibrosis allows staging of chronic liver disease without the need for liver biopsy, but this makes it difficult to determine whether the patient has advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis. For this reason, the concept of cACLD was introduced at the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop using two cut-off points that selected two groups of patients with a different risk of developing CSPH and therefore liver decompensation. Two meta-analyses15,16 have shown that the risk of liver disease-related complications is substantially increased in patients with liver stiffness >10 kPa.

A liver stiffness value below 10 kPa virtually rules out cACLD, while a value above 15 kPa is highly suggestive of itThe prevalence of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis in patients with liver stiffness below 10 kPa is very low, close to 10% in most studies comparing elastography with biopsy, although depending on the aetiology, the prevalence can vary between 4% and 20%.17–21 In terms of the incidence of events, the risk of liver disease-related complications in patients with liver stiffness <10 kPa (or cut-off points close to this value) is less than or equal to 1% at three years in most series.19,22–30 So, a liver stiffness value of less than 10 kPa virtually rules out cACLD.

A cut-off point above 15 kPa, however, selects a patient population with a prevalence of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis above 80% for most aetiologies.17,18,20,21,31,32 A recent series33 showed that the prevalence of portal hypertension (HVPG > 5 mmHg) in patients with a degree of liver stiffness >15 kPa was over 90% in most aetiologies, except in patients with MAFLD who were obese, where the prevalence was 64%. Not many studies have studied the incidence of events in patients with liver stiffness >15 kPa, although several have shown that as stiffness increases so does the risk of events. In a prospective cohort of patients with alcohol-related liver disease.19 the risk of developing liver disease-related complications (including alcoholic hepatitis) at four years in patients with liver stiffness >15 kPa was 54% compared to 3% in patients with liver stiffness values <10 kPa.

3. Diagnosis and relevance of clinically significant portal hypertensionIn patients with cirrhosis, the presence of HVPG equal to or greater than 10 mmHg indicates CSHPThe natural history of cirrhosis can be divided into two phases: a long compensated phase and a shorter decompensated phase.34 Within the compensated phase, one of the most important milestones in terms of prognosis is the development of CSPH, defined as an HVPG ≥ 10 mmHg, as its presence determines the risk of clinical decompensation. The definition of CSPH comes from longitudinal studies involving patients with cirrhosis of viral and alcohol-related aetiology in which it was found that patients with an HVPG ≤ 10 mmHg did not develop oesophageal varices or complications of portal hypertension (ascites, variceal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy), while the five-year risk of decompensation in patients with CSPH was approximately 40%.35 It has recently been shown that in patients with MAFLD-associated cirrhosis, the CSPH concept retains its prognostic capacity.36

In patients with MAFLD-associated cirrhosis, signs of CSPH may appear with HVPG values below 10 mmHgIn patients with cirrhosis of viral and alcoholic aetiology, the presence of oesophagogastric varices, portosystemic collaterals or clinical decompensation is anecdotal if HVPG is <10 mmHg. However, in patients with MAFLD cirrhosis it is possible to observe signs of CSPH or clinical decompensation with HVPG values <10 mmHg. A multicentre cross-sectional study showed that the prevalence of liver decompensation with an HVPG value <10 mmHg was 9% in patients with MAFLD cirrhosis compared to no decompensation among patients with hepatitis C virus cirrhosis, with ascites being the most frequently described complication.37 Additionally, a post hoc analysis of the 475 MAFLD patients with advanced disease (F3 and F4 fibrosis) included in simtuzumab trials identified seven cases (14%) of decompensation in patients with a baseline HVPG < 10 mmHg.36

In patients with alcoholic and viral cirrhosis and in non-obese patients with MAFLD, a liver stiffness value of 25 kPa or above diagnoses the presence of CSPH with reasonable accuracyA liver stiffness value below 15 kPa together with a platelet value above 150,000/mm3 rules out the presence of CSPH with reasonable diagnostic accuracy.

Following the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop, two publications contributed to refining and improving the assessment and stratification of patients with cACLD according to their risk of CSPH. The ANTICIPATE study38 provided risk prediction models for CSPH using the degree of liver stiffness measured by transient elastography plus platelet count in a population of patients with cACLD composed mainly of patients with viral and alcohol-related aetiology. These models were subsequently validated in a different cohort with a similar composition.33 In this multicentre study of more than 800 patients with cACLD, the prevalence of CSPH was 83.5%, 91% and 93.7% for liver stiffness values of 20, 25 and 30 kPa respectively. A liver stiffness value ≥25 kPa was chosen as the optimal cut-off point for diagnosing CSPH with a positive predictive value and specificity of over 90%. This liver stiffness cut-off was adequate for the diagnosis of CSPH in viral and alcohol-related cACLD, but not for patients with MAFLD cACLD and patients with obesity.

The exclusion of CSPH in patients with cACLD has been a difficult task. The use of the combination of liver stiffness and platelet count seems to perform better in ruling it out, and data from the above-mentioned multicentre study33 pointed in the same direction. Adding a platelet count ≥150,000/mm3 to a liver stiffness cut-off point ≤15 kPa could exclude CSPH with a negative predictive value and a sensitivity above 90% for most aetiologies (viral, alcohol-related and MAFLD).

These criteria for diagnosing and ruling out CSPH have subsequently been validated in numerous publications,39–41 including more than 500 patients, with positive and negative predictive values of 91.5% and 100% respectively. The recommendations for different cut-off points for liver stiffness by elastography have been established for patients with cACLD of viral aetiology and to a lesser extent alcohol or MAFLD, so values may vary for cACLD of other causes.

CSPH increases the risk of decompensation and death in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who undergo surgical resectionThe initial findings by Bruix et al.42 in a small series of cirrhotic patients with surgically resected HCC who had portal hypertension showed that they were at increased risk of postoperative decompensation. In a later study with a larger number of patients, CSPH and elevated bilirubin were shown to be the best predictors of mortality in the postoperative period after resection.43 Finally, in a systematic review of 11 studies, Berzigotti, et al.44 demonstrated that, in patients with compensated cirrhosis and HCC treated with surgery, the presence of CSPH almost doubled the three- and five-year mortality risk and tripled the risk of postoperative clinical decompensation.44

4. Screening for oesophagogastric varices at diagnosis of cirrhosis and after cure of hepatitis C virus infectionScreening endoscopy is recommended for patients with compensated cirrhosis who are not candidates for treatment with non-cardioselective beta-adrenergic blockers (NSBB) when they have liver stiffness values above 20 kPa or platelets below 150,000/mm3A controversial issue at present is when to perform endoscopic screening for oesophageal varices in patients with CSPH who cannot take NSBB. On the one hand, the PREDESCI45 study demonstrates the benefit, in terms of survival and decompensation, of treatment with NSBB in compensated patients with CSPH, which would already include adequate primary prophylaxis in those patients with at-risk varices. On the other, the ANTICIPATE study38 estimated that the likelihood of having varices at risk of bleeding requiring treatment is clearly lower in patients with a liver stiffness value <20 kPa and a platelet count >150,000/mm3. Lastly, patients with contraindications or intolerance to NSBB may benefit from treatment with endoscopic band ligation (EBL) as primary prophylaxis. Therefore, any patient with cACLD at risk for varices (especially those with liver stiffness >20 kPa or platelets <150,000/mm3) and contraindication or intolerance to NSBB should undergo screening endoscopy and EBL if appropriate. This recommendation has been taken up in the Baveno VII Consensus Workshop46 and in the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) consensus on the diagnosis and management of oesophago-gastric variceal bleeding.47

5. Long-term follow-up of the patient with hepatitis C virus cirrhosisAchieving sustained virologic response (SVR) after hepatitis C antiviral treatment is associated with a significant decrease in HVPG and reduces the risk of decompensationThe introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAA), with greater efficacy and a better safety profile than previous generations of antivirals, has made it possible to treat and cure most patients with advanced hepatitis C virus (HCV) liver disease. The first study to show the impact of SVR achieved by DAA on portal pressure included 60 patients with HVPG measurement before and after antiviral treatment who were stratified according to baseline (6–9; 10–15; ≥16 mmHg).48 SVR improved portal hypertension in all HVPG strata, although HVPG reduction was less likely in patients with HVPG ≥ 16 mmHg and therefore more advanced liver disease. A prospective Spanish multicentre study included 226 patients with CSPH in whom HVPG was measured at baseline and six months after completion of treatment and achievement of SVR.49 This study showed a significant mean decrease of 2.1 ± 3.2 mmHg in this short period of time, despite which 78% of patients remained with CSPH and therefore at risk of decompensation. At two years, these patients underwent a new haemodynamic study and 53% continued to have CSPH. Long-term follow-up of the Austrian cohort50 and the Spanish cohort51 found that the incidence of de novo decompensation or re-decompensation after SVR was low. Having an elevated baseline and/or post-treatment HVPG value and a history of previous decompensation were associated with an increased risk of decompensation after SVR. It is important to note that, in these studies, no patient whose HVPG dropped below 10 mmHg after SVR developed decompensation after three to four years of follow-up.

The presence of cofactors such as overweight, diabetes or alcohol consumption increases the risk of liver disease progression despite obtaining SVRAfter SVR, 10% of patients may have fibrosis progression.52 The presence of overweight or obesity, diabetes and alcohol consumption are important contributors to liver disease progression even after elimination/suppression of the primary aetiological factor and should be carefully assessed.53,54

In the absence of other risk co-factors, patients with hepatitis C who achieve SVR and consistently maintain liver stiffness values <12 kPa and platelets >150,000/mm3 can exit varices screening programmes.

The utility of non-invasive techniques to detect the presence of CSPH has been studied predominantly in patients with active HCV infection. A multicentre study evaluated 324 patients with HCV-associated portal hypertension who achieved SVR and had a post-treatment HVPG measurement.55 The prevalence of CSPH before and after treatment was 80% and 54% respectively. The combination of liver stiffness value and platelet count after SVR had a high diagnostic accuracy for estimating CSPH. Following SVR, a liver stiffness value <12 kPa associated with a platelet count >150,000/mm3 ruled out the presence of CSPH with a sensitivity of 99.2%. A liver stiffness value ≥25 kPa was highly suggestive of CSPH despite having obtained SVR (93.6%). No patients with liver stiffness <12 kPa and a platelet count >150,000/mm3 developed decompensation during a median follow-up of 36 months. These criteria, however, do not preclude further HCC screening in patients with advanced fibrosis as the risk persists despite achieving SVR.

6. Questions posed to the panel that did not reach consensusEndoscopy is recommended within 1−2 years in patients with HCV cirrhosis previously treated with NSBB in whom liver stiffness measured by transient elastography is less than 25 kPa after SVR. In the absence of varices, NSBB can be withdrawnThere are robust data indicating that cure of HCV infection in patients with CSPH is accompanied by a significant decrease in portal pressure.51 However, despite this reduction, up to 77% of patients continue to have an HVPG above 10 mmHg, and are therefore at risk of decompensation. In one recent study, Pons et al.33 demonstrated that in a series of 572 patients with cACLD and SVR after antiviral treatment, followed up for an average of 2.8 years, the incidence of decompensation was less than 1%. All decompensated patients had liver stiffness at baseline >20 kPa, and in 80% it did not change after cure of the infection.

In that same vein, in a retrospective analysis of 418 patients with paired transient elastography and HVPG measurements, Semmler et al.55 found that the three-year risk of decompensation in patients with liver stiffness <12 kPa and platelets >150,000 was 0%. These authors were able to confirm the utility of transient elastography in the assessment of CSPH in patients with SVR after antiviral therapy, with an even higher efficacy than that observed in patients with active infection.

It would seem reasonable to check for the absence of varices in all patients virologically cured of hepatitis C and whose liver stiffness is <25 kPa, especially in those with values <12-15 kPa, before considering withdrawal of NSBB. In making this decision, and in the absence of definitive prospective information, the tolerance to NSBB, the absence of co-factors of liver damage (for example, obesity and alcohol consumption) and the patient's opinion should be taken into account.

SESSION 2. Prevention of the first decompensation and recurrence (Table 2)1. Definition of decompensationThe presence of minimal ascites, identified only by ultrasound, is not considered as a decompensation of cirrhosisThe prognostic impact of minimal ascites, detected exclusively by imaging tests, has been evaluated in a limited number of studies,56–61 which differ in terms of design, 50% being retrospective, and in inclusion criteria. In addition, two of the studies did not include a control group without ascites.57,59 There are other significant limitations, such as the small number of patients with ascites detected by ultrasound. Furthermore, in at least half of the studies, the group of patients with ultrasound-detected ascites included individuals who had experienced other episodes of cirrhosis decompensation. Lastly, not all studies could conclusively confirm the prognostic impact of minimal ascites,58,61 so the prognostic value of ascites detected by ultrasound remains unknown. Therefore, with the information currently available, it is not possible to consider minimal ascites as decompensation of cirrhosis..

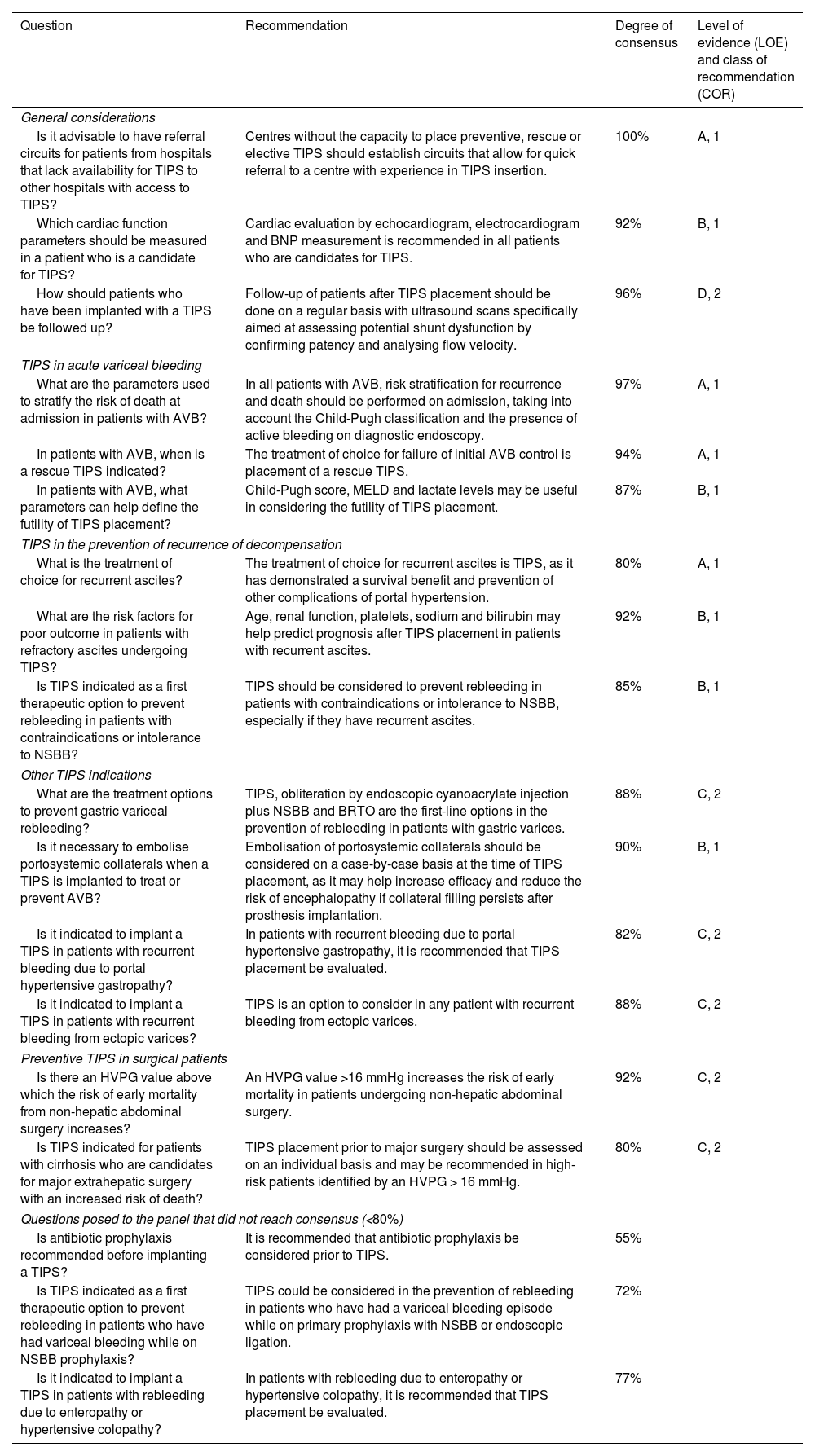

Recommendations on prevention of first decompensation and recurrence (session 2).

| Question | Recommendation | Degree of consensus | Level of evidence (LOE) and class of recommendation (COR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition of decompensation | |||

| Is ascites identified by ultrasound considered a decompensation of cirrhosis? | Minimal ascites, identified only by ultrasound, is not considered a decompensation of cirrhosis. | 80% | B, 1 |

| Is isolated jaundice considered a decompensation of cirrhosis? | There is not enough solid information to consider isolated jaundice a decompensation of cirrhosis. | 80% | D, 1 |

| Does the occurrence of a second decompensation event worsen the prognosis? | The occurrence of a second decompensation event worsens the prognosis. | 89% | B, 1 |

| Prevention of the first decompensation | |||

| What is the main risk factor for decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis? | The presence of CSPH is the main risk factor for decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis. | 96% | A, 1 |

| What is the treatment of choice to prevent the first decompensation in patients with cirrhosis? | Carvedilol is the drug of choice for the prevention of the first decompensation. | 89% | A, 1 |

| Should NSBB be given to patients with cirrhosis and CSPH? | In patients with CSPH, NSBB should be considered as prevention of the first decompensation. | 87% | B, 1 |

| Is band ligation indicated for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in patients intolerant to or with contraindication for NSBB? | Endoscopic band ligation is indicated for prophylaxis of first bleeding event in patients with high-risk varices intolerant to or with an absolute contraindication for NSBB, as it reduces the risk of bleeding, but not of other complications of portal hypertension. | 94% | A, 1 |

| Use of NSBB | |||

| Can carvedilol be used to prevent recurrence of variceal bleeding? | The available data support the use of carvedilol in the prevention of rebleeding. | 80% | B, 1 |

| Can carvedilol be used in patients with ascites? | Carvedilol can be used in patients with ascites, if its potential adverse effects are adequately monitored. | 82% | B, 2 |

| What are the limits for reducing the dose or stopping NSBB treatment in patients with cirrhosis? | In the case of arterial hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg) or acute kidney injury, NSBB should be discontinued or dosage reduced on an individual basis. | 96% | B, 1 |

| Can NSBB be used in the patient with cirrhosis and refractory ascites? | In patients with refractory ascites, the use of NSBB should be assessed on an individual basis. | 92% | B, 1 |

| Recompensation and portal hypertension | |||

| What does the concept of "recompensation" mean in cirrhosis? | The recompensation concept requires no recurrence of bleeding, encephalopathy (without lactulose or rifaximin) or ascites (without diuretics), in conjunction with normalisation of liver function parameters for at least 12 months. | 86% | C, 2 |

| Does recompensation mean the resolution of the CSPH? | Clinical recompensation does not necessarily mean resolution of CSPH. | 92% | B, 1 |

| Questions posed to the panel that did not reach consensus (<80%) | |||

| Is minimal hepatic encephalopathy considered a decompensation of cirrhosis? | There is not enough solid information to consider minimal encephalopathy as a decompensation of cirrhosis. | 70% | |

| Is bacterial infection other than SBP considered a decompensation of cirrhosis? | Bacterial infection other than SBP is not considered a decompensation of cirrhosis. | 62% | |

CSPH: clinically significant portal hypertension; NSBB: non-selective adrenergic beta-blockers; SBP: spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

The development of jaundice in patients with compensated cirrhosis has classically been regarded as a decompensation event, which rarely occurs in isolation as the first event, with the exception of chronic cholestatic disease.62 In the systematic review of the last Baveno VII Consensus Workshop, of the 116 studies evaluated in this regard, 32 included jaundice as a decompensation event.46 The incidence was reported in 18 of them,62–79 with 11 of them providing a heterogeneous definition (from >2 to ≥5 mg/dl). In the few studies (N = 9) where they differentiated whether or not jaundice was an isolated first event of decompensation, the rarity of this form of presentation was confirmed (0.7–3%), while in those where no such differentiation was made, the rate of jaundice development was much higher (2.9–73.9%). None of the studies specified the duration of the jaundice or whether a cause of superimposed liver damage (for example, bacterial/viral infections, hepatotoxicity or acute alcoholic hepatitis) was ruled out. Lastly, it cannot be ruled out that the development of jaundice reflected acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), as the current concept and definition of this syndrome post-dated the publication of most of the earlier studies. Therefore, further prospective studies are needed to determine whether jaundice represents a first decompensation or instead reflects additional liver damage or an episode of acute liver failure on a chronic background.

The occurrence of a second decompensation greatly worsens the prognosisThe development of a second decompensation event, either by recurrence of the initial decompensation (for example, second episode of encephalopathy or variceal bleeding) or by ascites-related complications (for example, refractory ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and/or hepatorenal syndrome), is associated with a significant worsening of survival.62,80–85

2. Prevention of the first decompensationCSPH is the main risk factor for decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosisAn HVPG ≥10 mmHg is defining of CSPH.46 This is because observational studies have established that HVPG, better than any other parameter, identifies patients with compensated cirrhosis at high risk of developing decompensation.35 The HVPG also identifies patients at risk of developing oesophagogastric varices and HCC.

Carvedilol is the drug of choice for the prevention of the first decompensationTreatment with NSBB is indicated in compensated patients with CSPH to prevent decompensation of cirrhosis. Randomised clinical studies have shown that in these patients NSBB significantly decreases the risk of developing a first decompensation, mainly by decreasing the risk of developing ascites, which is the most frequent complication in compensated patients.45 In patients with compensated cirrhosis, carvedilol is the NSBB of choice. Carvedilol has a vasodilatory effect due to its anti-〈-adrenergic action and so may attenuate the increased intrahepatic resistance that is a predominant mechanism for the development of portal hypertension in compensated cirrhosis.86 Carvedilol causes a greater decrease in HVPG than traditional NSBB and tends to be better tolerated.87 Clinical studies have shown a trend towards greater effectiveness in preventing decompensation than traditional NSBB. In addition, a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised studies versus placebo or EBL of varices in patients with at-risk varices found a significant improvement in survival in patients with compensated cirrhosis favouring the use of carvedilol,88 especially in patients with oesophageal varices.

In patients with CSPH, NSBB should be considered as prevention of the first decompensationPrevention of decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis is indicated in all patients with CSPH, whether or not they have varices.45 However, in patients with CSPH, the risk of decompensation is particularly high in those with varices, so the benefit obtained is also greater in these patients.45

EBL is indicated for prophylaxis of first bleeding event in patients with high-risk varices intolerant to or with an absolute contraindication for NSBB, as it reduces the risk of bleeding, but not of other complications of portal hypertension.

Both NSBB and EBL have been shown in randomised studies to decrease the risk of a first bleed in patients with at-risk oesophageal varices (large varices or small varices with red signs or in patients with advanced liver failure). A meta-analysis of studies comparing NSBB and EBL showed similar survival with both treatments in patients with at-risk varices.89 The risk of first bleeding event in these patients is also similar.90 A recent meta-analysis of comparative studies between NSBB and EBL, stratifying the results according to the presence or absence of decompensation, shows that NSBB achieves a significant improvement in survival over EBL in patients with compensated cirrhosis, mainly by reducing the risk of developing ascites. This suggests that in compensated patients with at-risk varices it is preferable to use NSBB. However, when these drugs are contraindicated, or when complications occur with treatment that require their withdrawal, EBL is the indicated treatment in both compensated and decompensated patients, as it significantly reduces the risk of bleeding.

3. Use of non-cardioselective beta-blockersAvailable data support the use of carvedilol in the prevention of rebleedingEBL in combination with NSBB therapy such as propranolol and carvedilol represents the treatment of choice for secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. In relation to the prevention of rebleeding and mortality risk, the use of NSBB is the key element of secondary prophylaxis.91,92 Randomised studies on prophylaxis for rebleeding have shown that carvedilol monotherapy has similar efficacy to EBL93 and to combination therapy with nadolol and isosorbide mononitrate.94 However, the likelihood of rebleeding is higher in patients treated with single modality therapy versus combination therapy. Both the combinations of carvedilolol and EBL and propranolol/nadolol and EBL have shown greater efficacy in the prevention of rebleeding and in the prevention of other non-haemorrhagic decompensations,95 as well as a greater decrease in HVPG in the short term (first month post-bleed),96 with a better haemodynamic response rate (53% vs. 29%) and longer-term survival.97

Carvedilol can be used in patients with ascites if its potential adverse effects are adequately monitoredAscites is the most common complication in the natural history of cirrhosis and its occurrence is a progression from the compensated to the decompensated stage. A meta-analysis of 15 clinical trials, including 452 patients with ascites treated with NSBB, showed that patients with haemodynamic response (HVPG reduction <12 mmHg or >20% from baseline) were less likely to develop decompensated cirrhosis than non-responders.98 It should also be noted that treatment with NSBB can have a significant impact on cardiocirculatory status, which may affect patient survival. Related to this, a single-centre study in patients with ascites on primary prophylaxis with NSBB demonstrated an increased risk of refractory ascites and poorer short-term survival in those with cardiac output or cardiac index below 5 and 3 l/min.99 However, the available information on the efficacy and safety of carvedilol treatment in patients with ascites is limited, as it is based on only two retrospective studies. A first single-centre study of 264 patients with ascites treated with carvedilol at a dose of 12.5 mg showed better long-term survival in those treated with carvedilol.100 In the same vein, retrospective analysis of a multicentre clinical trial comparing the long-term effect of treatment with carvedilol (dose: 6.25–12.5 mg; 49% with ascites) versus EBL (53% with ascites) showed longer survival in patients treated with carvedilol (7.8 vs. 4.2 years).101

In the case of hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg) or acute kidney injury, NSBB should be discontinued or the dose reducedAs cirrhosis progresses, compensatory cardiac mechanisms help maintain renal perfusion in patients with diuretic-sensitive ascites. However, when ascites is refractory, these cardiac mechanisms can no longer compensate for the worsening arterial vasodilation, leading to a reduction in organ perfusion.102 Due to their negative inotropic effect, NSBB may upset the fragile cardiodynamic balance and impair renal perfusion, so careful review of dosage is advised in these patients. Based on the results of a study in patients with diuretic-refractory and diuretic-responsive ascites treated with NSBB,103 the Baveno VII Consensus Workshop recommended that in patients with persistent hypotension (mean arterial blood pressure <65 mmHg or systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg) or hepatorenal syndrome, NSBB should be discontinued and reintroduced at lower doses with careful monitoring. In severe infection, such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), it has also been suggested that maintaining NSBB treatment may increase the risk of hepatorenal syndrome and death.104 Furthermore, in decompensated patients on the transplant list, treatment with NSBB has been associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury,105 mainly in patients with ascites and previous kidney failure106 or worse liver function (Child-Pugh C).107 However, in patients on the transplant list, the use of NSBB has been associated with improved short-term survival. Therefore, it is suggested that the use of NSBB in this population (with infection, hypotension or acute kidney injury) should be individually tailored to the changing circumstances observed in these patients and should be reserved for those with better cardiac and haemodynamic reserve.108

In patients with refractory ascites, the use of NSBB should be assessed on an individual basisRefractory ascites is a common decompensation in the later stages of decompensated cirrhosis.34 In patients with refractory ascites, NSBB block compensatory cardiac mechanisms and promote worsening peripheral vasodilation, reducing renal perfusion pressure, which promotes the development of renal failure and reduces survival.103 However, the harmful effect occurs when NSBB are used at high doses. A single-centre, prospective, observational study, and another with a crossover design, carried out in patients with refractory ascites both found that the use of high-dose propranolol (160 mg/day) increased the mortality risk 2.6-fold compared to patients not treated with NSBB, mainly due to increased circulatory dysfunction after large-volume ascites.109,110 In the same vein, four retrospective studies showed the possible harmful effect of NSBB use in different clinical scenarios such as Child-Pugh C patients111 and those with refractory ascites,112 mainly due to the risk of acute kidney injury.105 Therefore, in these groups, it is recommended to discontinue NSBB or to reduce the dose, adapting it to the individual conditions of each patient.

In contrast, treatment with low-dose NSBB has been shown to reduce mortality rates113 in patients on the liver transplant list. In patients with infections such as SBP, NSBB reduce the mortality rate114 or do not increase it, especially if a mean blood pressure above 65 mmHg is maintained. There may therefore be a haemodynamic window for maintaining NSBB in these contexts.115 Lastly, the prospective CANONIC study showed that maintaining NSBB treatment in patients with ACLF modifies the inflammatory response and is associated with lower mortality rates.116 Therefore, in patients with refractory ascites, with a resulting fragile cardiodynamic balance, personalised treatment is recommended.

4. Recompensation and portal hypertensionThe recompensation concept requires no recurrence of bleeding, encephalopathy (without lactulose/rifaximin) or ascites (without diuretics), in conjunction with normalisation of liver function parameters for at least 12 monthsThere is growing evidence to support the fact that adequate control of the cause of liver disease has a significant impact on the natural history of cirrhosis. Aetiological treatment has the potential to halt disease progression and dramatically reduce the likelihood of experiencing future episodes of decompensation.

In this regard, hepatic recompensation has been defined as the absence of episodes of hepatic decompensation such as variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy (without lactulose/rifaximin) or ascites (without diuretics) combined with normalisation of liver function for at least 12 months. The possibility of recompensation has been described in patients with prolonged abstinence from alcohol use or in those with viral hepatitis where control or elimination of the aetiological agent has been achieved (suppression of hepatitis B virus replication in the absence of delta virus co-infection; HCV clearance with SVR). This definition is based on the available data from numerous studies, which have shown that some of the patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis on the waiting list for liver transplantation can be removed from the waiting list due to improved liver function.117,118 Similarly, after elimination of C virus or suppression of B virus replication, there is a significant improvement in liver function with a marked reduction in the likelihood of decompensation.119–123 Although the concept of recompensation has been defined in the context of alcoholic liver disease and viral hepatitis, recent evidence suggests that it may also extend to diseases such as metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease.124 The improvement in liver function, as well as the decrease in the likelihood of decompensation is not universal after elimination of the aetiological factor, so a minimum time of 12 months has been established before a diagnosis of recompensation can be made.

Clinical recompensation does not necessarily mean resolution of the CSPHHaemodynamic studies in patients with HCV cirrhosis50,51 have shown persistence of CSPH after SVR in 50% of patients with an elevated HVPG (≥16 mmHg) at baseline. It should not therefore be assumed that the risk of decompensation will disappear universally after elimination of the aetiological agent, despite an improvement in liver function. However, in patients in whom an SVR results in an HVPG <10 mmHg, the likelihood of decompensation during follow-up is virtually zero, provided that other factors that might influence the natural history of cirrhosis (for example, drug use and metabolic syndrome) are adequately controlled.

5. Questions posed to the panel that did not reach consensusThere is not enough solid information to consider minimal encephalopathy as a decompensation of cirrhosisStudies which have assessed the prognostic impact of minimal hepatic encephalopathy have a number of limitations.78,125–136 First, the population included in the studies was heterogeneous with respect to age, aetiology, comorbidities, or stage of cirrhosis. Three studies included patients with occult hepatic encephalopathy (minimal and grade 1 of the West-Haven classification)128,132,133 and most included both compensated and decompensated patients (including previous overt hepatic encephalopathy). In the only study that looked at them separately, the number of compensated patients was relatively small and in one third of patients with compensated cirrhosis and minimal hepatic encephalopathy who progressed to more advanced stages, it was due to the development of oesophageal varices rather than decompensation events.78 Second, the diagnostic tests varied between studies and the statistical methodology for assessing prognostic impact was heterogeneous and mostly suboptimal, with competing risk analyses performed in only two studies.78,136 Finally, follow-up was generally short (<14 months in 67% of studies) for assessing decompensation and/or mortality in patients with compensated cirrhosis and not all studies were able to confirm its prognostic impact.126,127,132 Further prospective studies are therefore needed to clarify the prognostic impact of minimal encephalopathy and to determine whether it can be considered a decompensation of cirrhosis.

Bacterial infection other than SBP is not considered a decompensation of cirrhosisIn a cohort of 1,672 patients with compensated cirrhosis of viral origin followed up prospectively, bacterial infections were found to be a common event and were associated with an increased risk of decompensation and death. However, it was not discerned whether the increased mortality risk occurred once the patient had a decompensation event.137 Two recent studies have provided information on this issue. A nested analysis of the PREDESCI study45 confirmed the high prevalence of bacterial infections in compensated cirrhosis and their prognostic impact, although mortality occurred once the decompensated phase developed.138 Similar results were found in a secondary analysis of a prospective two-centre study in which the development of isolated infection (i.e. without associated decompensation) was not associated with an increase in the mortality rate.79 These studies support bacterial infections being a trigger for decompensation, but in the absence of decompensation there is no precise information about their impact on mortality rates and, consequently, they cannot be considered a form of decompensation. There are even fewer data on the prevalence and impact of bacterial infections in patients with compensated cirrhosis without CSPH.

SESSION 3. Acute oesophagogastric variceal bleeding (Table 3)1. General managementIt is recommended that patients with acute variceal bleeding (AVB) be treated in intensive care units or specific intermediate unitsConsidering the still high mortality rate for AVB,139 different expert opinions indicate that the treatment of these patients should be carried out in units with specialised staff and capacity for the treatment of critically ill patients.140,141

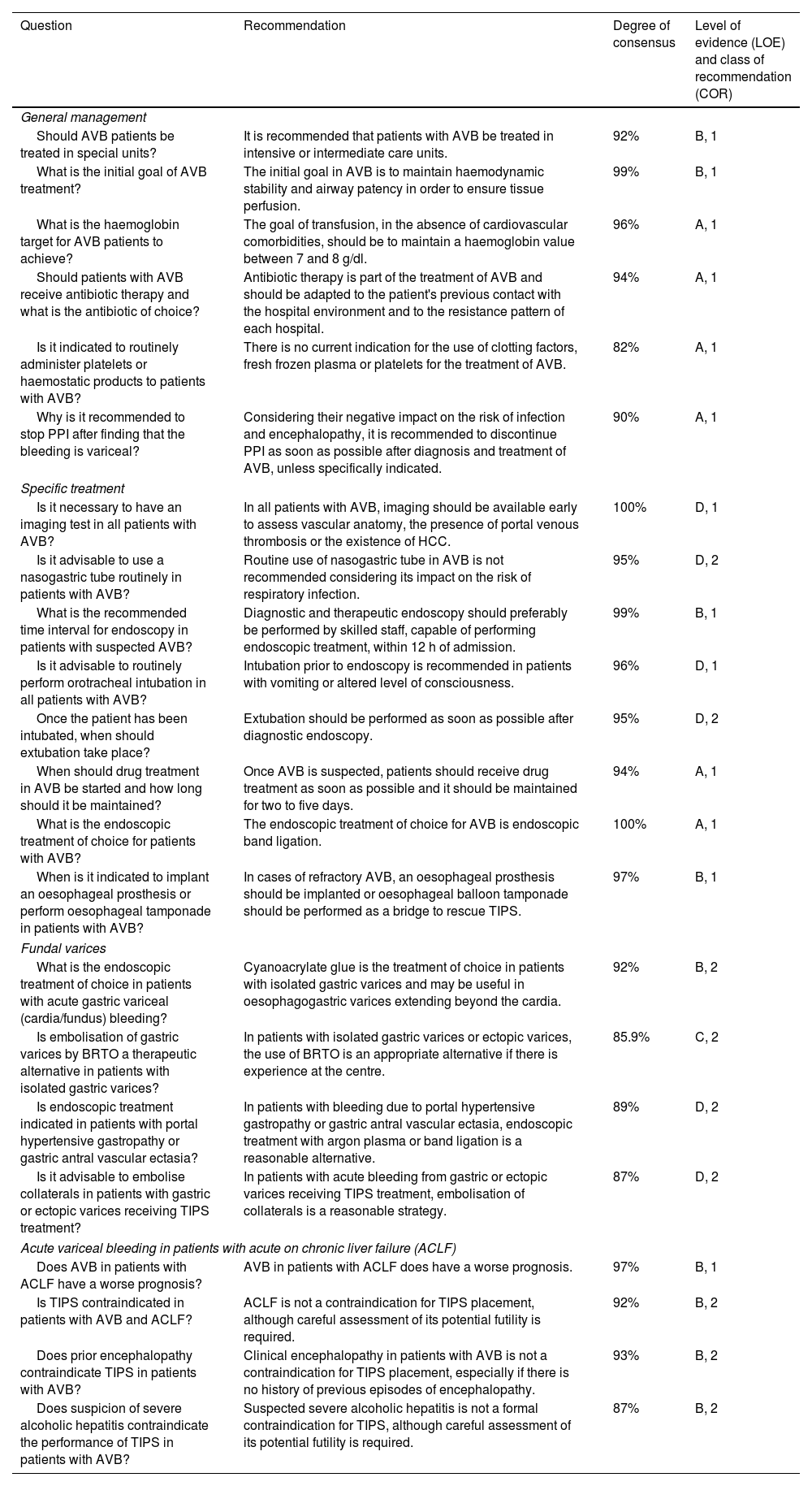

Recommendations on acute oesophagogastric variceal bleeding (session 3).

| Question | Recommendation | Degree of consensus | Level of evidence (LOE) and class of recommendation (COR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General management | |||

| Should AVB patients be treated in special units? | It is recommended that patients with AVB be treated in intensive or intermediate care units. | 92% | B, 1 |

| What is the initial goal of AVB treatment? | The initial goal in AVB is to maintain haemodynamic stability and airway patency in order to ensure tissue perfusion. | 99% | B, 1 |

| What is the haemoglobin target for AVB patients to achieve? | The goal of transfusion, in the absence of cardiovascular comorbidities, should be to maintain a haemoglobin value between 7 and 8 g/dl. | 96% | A, 1 |

| Should patients with AVB receive antibiotic therapy and what is the antibiotic of choice? | Antibiotic therapy is part of the treatment of AVB and should be adapted to the patient's previous contact with the hospital environment and to the resistance pattern of each hospital. | 94% | A, 1 |

| Is it indicated to routinely administer platelets or haemostatic products to patients with AVB? | There is no current indication for the use of clotting factors, fresh frozen plasma or platelets for the treatment of AVB. | 82% | A, 1 |

| Why is it recommended to stop PPI after finding that the bleeding is variceal? | Considering their negative impact on the risk of infection and encephalopathy, it is recommended to discontinue PPI as soon as possible after diagnosis and treatment of AVB, unless specifically indicated. | 90% | A, 1 |

| Specific treatment | |||

| Is it necessary to have an imaging test in all patients with AVB? | In all patients with AVB, imaging should be available early to assess vascular anatomy, the presence of portal venous thrombosis or the existence of HCC. | 100% | D, 1 |

| Is it advisable to use a nasogastric tube routinely in patients with AVB? | Routine use of nasogastric tube in AVB is not recommended considering its impact on the risk of respiratory infection. | 95% | D, 2 |

| What is the recommended time interval for endoscopy in patients with suspected AVB? | Diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy should preferably be performed by skilled staff, capable of performing endoscopic treatment, within 12 h of admission. | 99% | B, 1 |

| Is it advisable to routinely perform orotracheal intubation in all patients with AVB? | Intubation prior to endoscopy is recommended in patients with vomiting or altered level of consciousness. | 96% | D, 1 |

| Once the patient has been intubated, when should extubation take place? | Extubation should be performed as soon as possible after diagnostic endoscopy. | 95% | D, 2 |

| When should drug treatment in AVB be started and how long should it be maintained? | Once AVB is suspected, patients should receive drug treatment as soon as possible and it should be maintained for two to five days. | 94% | A, 1 |

| What is the endoscopic treatment of choice for patients with AVB? | The endoscopic treatment of choice for AVB is endoscopic band ligation. | 100% | A, 1 |

| When is it indicated to implant an oesophageal prosthesis or perform oesophageal tamponade in patients with AVB? | In cases of refractory AVB, an oesophageal prosthesis should be implanted or oesophageal balloon tamponade should be performed as a bridge to rescue TIPS. | 97% | B, 1 |

| Fundal varices | |||

| What is the endoscopic treatment of choice in patients with acute gastric variceal (cardia/fundus) bleeding? | Cyanoacrylate glue is the treatment of choice in patients with isolated gastric varices and may be useful in oesophagogastric varices extending beyond the cardia. | 92% | B, 2 |

| Is embolisation of gastric varices by BRTO a therapeutic alternative in patients with isolated gastric varices? | In patients with isolated gastric varices or ectopic varices, the use of BRTO is an appropriate alternative if there is experience at the centre. | 85.9% | C, 2 |

| Is endoscopic treatment indicated in patients with portal hypertensive gastropathy or gastric antral vascular ectasia? | In patients with bleeding due to portal hypertensive gastropathy or gastric antral vascular ectasia, endoscopic treatment with argon plasma or band ligation is a reasonable alternative. | 89% | D, 2 |

| Is it advisable to embolise collaterals in patients with gastric or ectopic varices receiving TIPS treatment? | In patients with acute bleeding from gastric or ectopic varices receiving TIPS treatment, embolisation of collaterals is a reasonable strategy. | 87% | D, 2 |

| Acute variceal bleeding in patients with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) | |||

| Does AVB in patients with ACLF have a worse prognosis? | AVB in patients with ACLF does have a worse prognosis. | 97% | B, 1 |

| Is TIPS contraindicated in patients with AVB and ACLF? | ACLF is not a contraindication for TIPS placement, although careful assessment of its potential futility is required. | 92% | B, 2 |

| Does prior encephalopathy contraindicate TIPS in patients with AVB? | Clinical encephalopathy in patients with AVB is not a contraindication for TIPS placement, especially if there is no history of previous episodes of encephalopathy. | 93% | B, 2 |

| Does suspicion of severe alcoholic hepatitis contraindicate the performance of TIPS in patients with AVB? | Suspected severe alcoholic hepatitis is not a formal contraindication for TIPS, although careful assessment of its potential futility is required. | 87% | B, 2 |

ACLF: acute-on-chronic liver failure; AVB: acute variceal bleeding; BRTO: balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; PPI: proton pump inhibitors; TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Initial management of AVB should be aimed at haemodynamic and general stabilisation of the patient, with attention to careful monitoring of blood pressure, urine output and oxygen saturation.140,141 Volume replacement should be initiated early with the goal of maintaining a mean arterial pressure >65 mmHg. Crystalloids are the solutions of choice as they have fewer haemostasis disturbances and less anaphylactic reactions. It is essential to protect the airway, especially in patients with altered levels of consciousness.142

The aim of transfusion, in the absence of cardiovascular comorbidities, should be to maintain a haemoglobin value between 7 and 8 g/dlStudies in rats with pre-hepatic portal hypertension almost 40 years ago suggested that non-restrictive transfusion in an experimental haemorrhage model increased portal pressure.143 Subsequently, a randomised study144 demonstrated that a restrictive transfusion policy (transfusion threshold of 7 g/dl haemoglobin) improved survival of patients with variceal bleeding. HVPG increased in patients randomised to receive a non-restrictive transfusion. Therefore, in the absence of cardiovascular comorbidities, the haemoglobin threshold for AVB should be between 7 and 8 g/dl.

Antibiotic treatment is part of AVB therapy and should be adapted to the patient's previous contact with the hospital environment and to the resistance pattern of each hospitalSeveral studies and meta-analyses have suggested that early administration of antibiotics in AVB is associated with a decreased incidence of bacterial infections during the episode and lower overall and infection-induced mortality rates, as well as a shorter hospital stay and reduced likelihood of rebleeding.145,146 However, there is no universal recommendation for determining the type of antibiotic. One controlled study147 identified that IV ceftriaxone (1 g/24 h) was superior to norfloxacin in terms of development of any type of infection, severe infection, SBP or bacteraemia. A recent retrospective observational study148 suggested that the beneficial impact of antibiotic prophylaxis was null in Child-Pugh A patients, although these data require validation. Lastly, the frequent occurrence of infections with multidrug-resistant organisms in patients with cirrhosis and the importance of their early treatment make it advisable to adapt the antibiotic regimen to the local prevalence of resistant microorganisms and to the antibiotic administration policies of each centre.46

There is no current indication for the use of clotting factors, fresh frozen plasma or platelets for the treatment of AVBHaemostasis in cirrhosis is re-balanced by the existence of numerous pro-haemorrhagic and pro-thrombotic changes in its different phases. Classic coagulation assessment parameters (especially INR) do not accurately reflect the haemostatic balance in the cirrhotic patient. Furthermore, the cause of AVB is increased portal pressure and variceal wall tension, not impaired haemostasis.

A recent observational study showed that administration of fresh frozen plasma (adjusted for age, MELD and presence of HCC) in AVB was associated with an increased risk of rebleeding, higher mortality rate and longer hospital stay.149 A recent meta-analysis reported that recombinant Factor VIIa administration, despite improving the likelihood of a combined event (defined as bleeding control, prevention of recurrence at day 5 and mortality at day 5) in patients with AVB at initial endoscopy, was associated with an increased risk of arterial thrombotic events.150 The high cost of the drug has also been seen as a major drawback to its use.151 Lastly, a recent study to assess the efficacy of tranexamic acid in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding did not demonstrate any benefit, either overall or in the subgroup of patients with AVB. In addition, the use of this drug increased the risk of thrombotic events and seizures.152 Therefore, there is currently no indication for systematic correction of coagulation disorders in AVB.

Considering their negative impact on the risk of infection and encephalopathy, it is recommended to discontinue proton pump inhibitors (PPI) as soon as possible after diagnosis and treatment of AVB, unless specifically indicatedPPI are widely used in many different contexts, often without a precise indication. Several studies have identified that PPI use increases the risk of bacterial infection in patients with ascites153 as well as the risk of hepatic encephalopathy and mortality.154,155 In addition, the use of PPI negatively impacts the natural history of SBP, with an increased risk of kidney failure, severe encephalopathy and death.156 Chronic PPI use has also been associated with an increased incidence of fractures in patients with cirrhosis157 and an increased risk of encephalopathy after insertion of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).158 Lastly, a large retrospective observational study159 indicated that PPI administration was dose-dependently associated with an increased risk of infection, decompensation and possibly liver disease-related death. However, in patients hospitalised for acute bleeding, the use of PPI had a protective effect. Ultimately, the use of PPI in AVB is justified in the acute phase of the haemorrhage and should only be maintained in the long term in the presence of a recognised indication for their use.

2. Specific treatmentIn all patients with AVB, imaging should be available early to assess vascular anatomy, the presence of portal thrombosis or the existence of HCCIn patients with AVB, it is not uncommon for there to be co-factors affecting the occurrence of bleeding, its severity and its appropriate treatment. These include the presence of portal thrombosis or HCC160,161 (with or without malignant portal vein thrombosis). In addition, the potential need for TIPS in the context of AVB requires an appropriate vascular map to identify the possibility of or potential technical difficulties in performing the procedure. Lastly, an axial imaging test, preferably computed tomography (CT), may be useful in the diagnosis of other possible co-factors that may influence decision-making46 (for example, extrahepatic neoplasms and thoracic pathology).

Routine use of nasogastric tube in AVB is not recommended considering its impact on the risk of respiratory infectionNasogastric tube placement with lavage does not predict the presence of high-risk lesions requiring endoscopic treatment and is not without adverse effects such as pain and epistaxis, in addition to failure of tube placement in up to 34% of cases47 and increased risk of respiratory infections. In addition, a randomised study found no difference in the likelihood of rebleeding or mortality risk and does not recommend its use.162

Diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy should preferably be performed by expert staff, capable of performing endoscopic treatment, within 12 h of admissionGiven the high mortality rate of AVB, the availability of an endoscopist with expertise in haemostatic techniques is essential at all times. A cohort study showed that in patients with haematemesis on admission, performing endoscopy within 12 h of hospital admission increased the likelihood of rebleeding and mortality at six weeks.163 Another study including 516 patients with gastrointestinal haemorrhage (only 10% with AVB) showed that performing endoscopy very early (before 6 h) offers no survival benefit, emphasising the importance of adequate resuscitation and appropriate medical management prior to endoscopy. However, there is great heterogeneity in the literature regarding the definition of appropriate times for endoscopy, which makes it difficult to analyse. One recent meta-analysis164 involving 2,824 patients with haemorrhage suggests that early endoscopy (before 12 h) can almost halve the overall mortality of cirrhotic patients with AVB. Therefore, in cases of AVB with haemodynamic instability or haematemesis, endoscopy should be performed as early as possible once the patient is stabilised.46

Intubation prior to endoscopy is recommended in patients with vomiting or altered level of consciousnessRoutine intubation prior to diagnostic endoscopy is not recommended in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Several meta-analyses show that prophylactic intubation prior to endoscopy in all patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding may be associated with increased risk of aspiration and pneumonia, longer hospital stay and potentially higher mortality rates,165,166 with similar results in patients with AVB.167 However, patients with haematemesis, agitation or hepatic encephalopathy are at high risk of bronchoaspiration, so prophylactic intubation should be considered in these cases prior to endoscopy to ensure airway protection.46,47

Extubation should be performed as soon as possible after diagnostic endoscopyAirway manipulation is a risk factor for respiratory infection in the context of AVB,168 so early extubation is advisable if the patient's clinical situation permits.46,47

Once AVB is suspected, patients should receive drug treatment as soon as possible and it should be maintained for two to five daysStarting vasoconstrictor drugs before endoscopy decreases the incidence of active bleeding during endoscopy and facilitates endoscopic management.169,170 One meta-analysis, which included 30 studies and 3,111 patients with AVB, shows that patients who received early vasoconstrictive therapy had a lower mortality rate (all-cause), lower transfusion requirements, improved bleeding control and shorter hospital stay.171 The drugs of choice in AVB are somatostatin, terlipressin and octreotide, with no differences in terms of mortality rate, safety or rebleeding rate,172,173 although somatostatin and octreotide have fewer adverse effects. Some studies suggest that a shorter duration of treatment (2−3 days) may not influence the recurrence rate.174,175 However, the limited sample size and the lack of predictive factors for poor prognosis to guide the decision makes it difficult to extrapolate a recommendation. In specific situations, such as in patients with optimal liver function and no risk factors for recurrence, shorter regimens could be considered, pending definitive data.176,177

The endoscopic treatment of choice for AVB is EBLEBL has been shown to be superior to sclerotherapy in the initial control of AVB (90%), also halving the likelihood of rebleeding with fewer adverse effects and lower mortality rates.178,179 No benefit has been found from combined endoscopic therapy of EBL with sclerosis.180 The combination of vasoconstrictor drugs and EBL has demonstrated superiority in terms of efficacy, safety and mortality rates in the treatment of AVB (control of the acute episode 90%, prevention of early recurrence 80%) and is therefore the treatment of choice in patients with AVB.

In cases of refractory AVB, an oesophageal prosthesis should be implanted or oesophageal balloon tamponade should be performed as a bridge to rescue TIPSDespite adequate treatment of AVB, up to 15% of patients experience early rebleeding, often requiring haemostatic treatment as a bridge until rescue TIPS is performed. The same is true in cases of massive bleeding. In these circumstances, both the placement of an oesophageal prosthesis and oesophageal balloon tamponade are appropriate options. There is only one randomised controlled study comparing the two alternatives181; in this study, oesophageal prostheses were shown to be superior in controlling bleeding with less transfusion requirements and fewer adverse effects. However, no difference was found in survival at six weeks and, in addition, 25% of the prostheses migrated. In addition, there is a benefit in terms of insertion time as tamponade balloons must be deflated within 24 h of insertion while the prosthesis can remain in situ without efficacy diminishing for up to 7–14 days, which may be important in patients with a temporary contraindication to TIPS placement (for example, active infection). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the two alternatives corroborates these results, proposing oesophageal prostheses as an equally effective, but safer, option to tamponade.182

3. Gastric fundus varicesCyanoacrylate glue is the treatment of choice in patients with isolated gastric varices and may be useful in oesophagogastric varices extending beyond the cardiaGastric varices are classified according to the Sarin et al. classification, which divides them into varices located at the oesophagogastric junction and isolated gastric or cardia/fundal varices.183 Cyanoacrylate injection is applied endoscopically to treat isolated gastric AVB. Several systematic reviews with meta-analyses have evaluated the efficacy of cyanoacrylate injection, demonstrating that this technique is superior in terms of efficacy and safety and is therefore first choice.184–186

Embolisation by balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is an alternative to endoscopic treatment or TIPS in patients with gastric or ectopic varices. Experience in our setting is limited, but it is an appropriate alternative in centres with experience.187,188 This technique involves occlusion of blood flow by means of a balloon catheter which enables instillation of a sclerosing agent proximal to the occlusion site. The success rates of BRTO and TIPS for bleeding control are similar. However, with BRTO there is a lower likelihood of developing hepatic encephalopathy,189 although it may worsen portal hypertension and aggravate oesophageal varices and/or ascites; these data need to be confirmed in further studies.

In patients with bleeding due to portal hypertensive gastropathy or gastric antral vascular ectasia, endoscopic treatment with argon plasma, ligation or other methods is a reasonable alternativeThe initial treatment for portal hypertensive gastropathy is NSBB. In patients who bleed due to gastropathy despite medical treatment, endoscopic treatment may be considered, although data are limited. Some studies indicate that in this subgroup of patients, endoscopic treatment with argon plasma may reduce transfusion requirements.190,191 The treatment of choice for patients with gastric antral vascular ectasia and chronic anaemia or bleeding is endoscopic. The initial approach is with argon plasma, although recurrence rates are high and patients require several sessions.192 For patients without a good response to argon, EBL of the antrum is recommended. A systematic review with meta-analysis showed that patients treated with ligation had significantly lower post-procedural transfusion requirements than those treated with argon plasma; in addition, EBL was associated with fewer endoscopic sessions and fewer transfusions in the long term.193

In patients with gastric or ectopic AVB receiving TIPS treatment, embolisation of collaterals is a reasonable strategyPatients having TIPS for the treatment of gastric variceal bleeding have a 15% likelihood of re-bleeding.194 TIPS can be combined with collateral bed embolisation to control bleeding or reduce the risk of recurrent variceal bleeding from gastric or ectopic varices (mainly large isolated varices), particularly in cases where, despite a decrease in PPG, portal flow remains diverted to the collaterals.195 Studies with few patients suggest that combination therapy improves eradication of gastric varices with a reduced likelihood of rebleeding, although with no benefit in terms of survival.195,196

4. Gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute on chronic liver failureAVB in patients with ACLF has a worse prognosisDespite great advances in the prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding due to portal hypertension, it remains one of the most lethal complications in patients with cirrhosis.197 ACLF increases the risk of rebleeding and decreases survival.198

ACLF is not a contraindication for TIPS placement, although careful assessment of its potential futility is requiredIn the context of AVB and ACLF, placement of TIPS, both rescue and preventive, is associated with improved bleeding control and a lower mortality rate.199,200 However, there is limited published information on this issue in patients with three or more organ failures (ACLF 3). Studies published to date have failed to establish specific futility criteria in this situation and knowledge about the benefit of TIPS in this subgroup of more severe patients is therefore insufficient.201,202 In such cases, the risk/benefit of TIPS placement must be weighed up on a case-by-case basis.

The existence of clinical HE in patients with AVB is not a contraindication for TIPS placement, especially if there is no history of previous episodes of HEHE is common in the context of AVB. In particular, patients with a high risk of rebleeding (Child-Pugh C 10–13 or Child-Pugh B with active bleeding at the time of endoscopy) have a higher prevalence of HE on admission compared to patients at low risk (39.2% vs. 10.6%).203 The occurrence of clinical HE or worsening of minimal HE after TIPS placement is also a common event, occurring in up to 35% of patients who have preventive TIPS.204,205 For this reason, the risk-benefit ratio of this intervention in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding and a history of HE, or with HE on admission, has been the subject of debate. Recent studies have shown that early TIPS placement increases one-year survival without increasing the risk of HE.203–205 Moreover, a number of HE prevention and treatment measures are now available in this setting which have proven effective, such as the use of covered TIPS206 or smaller diameter TIPS (8 vs. 10 mm)207 and the administration of lactulose and/or prophylactic rifaximin.208,209

Suspected severe alcoholic hepatitis is not a formal contraindication for TIPS, although careful assessment of its potential futility is requiredTo date, the impact of severe alcoholic hepatitis on patients receiving a TIPS for AVB has not been specifically analysed. However, other variables such as MELD score, Child-Pugh, age, serum lactate and other factors have been shown to be useful predictors of survival after TIPS placement.202,210–212 Alcohol consumption was not an important determinant of rebleeding risk or mortality in any of these studies. Therefore, acute alcoholic hepatitis should not be considered a priori as a contraindication for TIPS placement, the relevance of which should be established by current criteria in clinical practice guidelines irrespective of the aetiology of cirrhosis or the origin of decompensation.

SESSION 4. Other complications of portal hypertension (Table 4)1. Hepatic encephalopathyRifaximin is indicated for secondary HE prophylaxis after a second episode of clinical HE occurring within six months of the initial episodeRifaximin decreased the risk of HE recurrence in a randomised clinical trial in patients with cirrhosis who had had a previous episode in the past six months. Compared to the placebo group, the rifaximin-treated group had fewer episodes of HE (22% vs. 45%) and hospitalisation (13.6% vs. 22.6%).213 In this study, 90% of the patients included were on concomitant treatment with lactulose, which makes it advisable in clinical practice to combine the two drugs. This beneficial effect of combination therapy was confirmed in a meta-analysis.214

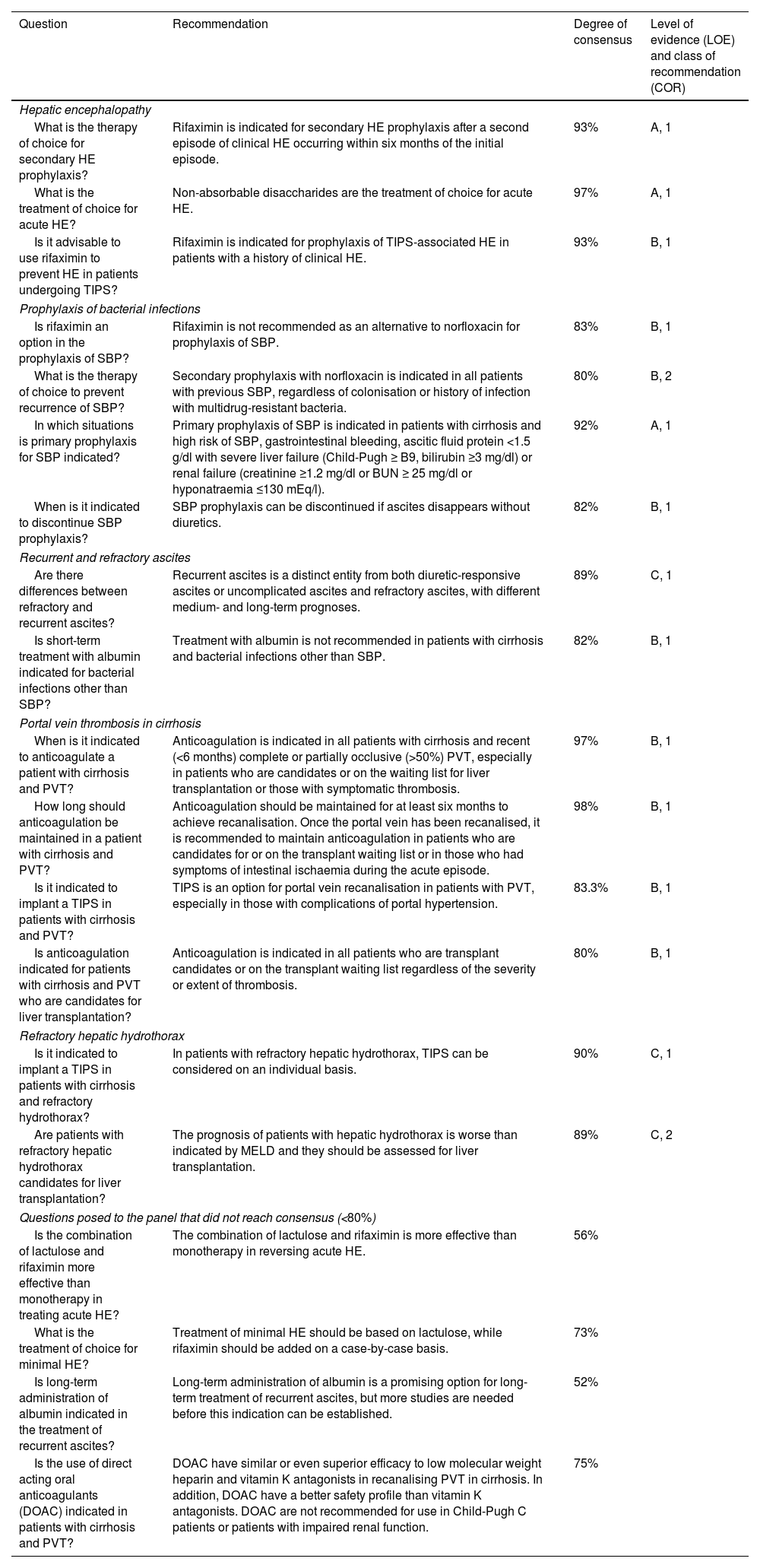

Recommendations on other complications of portal hypertension (session 4).

| Question | Recommendation | Degree of consensus | Level of evidence (LOE) and class of recommendation (COR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic encephalopathy | |||

| What is the therapy of choice for secondary HE prophylaxis? | Rifaximin is indicated for secondary HE prophylaxis after a second episode of clinical HE occurring within six months of the initial episode. | 93% | A, 1 |

| What is the treatment of choice for acute HE? | Non-absorbable disaccharides are the treatment of choice for acute HE. | 97% | A, 1 |

| Is it advisable to use rifaximin to prevent HE in patients undergoing TIPS? | Rifaximin is indicated for prophylaxis of TIPS-associated HE in patients with a history of clinical HE. | 93% | B, 1 |

| Prophylaxis of bacterial infections | |||

| Is rifaximin an option in the prophylaxis of SBP? | Rifaximin is not recommended as an alternative to norfloxacin for prophylaxis of SBP. | 83% | B, 1 |

| What is the therapy of choice to prevent recurrence of SBP? | Secondary prophylaxis with norfloxacin is indicated in all patients with previous SBP, regardless of colonisation or history of infection with multidrug-resistant bacteria. | 80% | B, 2 |

| In which situations is primary prophylaxis for SBP indicated? | Primary prophylaxis of SBP is indicated in patients with cirrhosis and high risk of SBP, gastrointestinal bleeding, ascitic fluid protein <1.5 g/dl with severe liver failure (Child-Pugh ≥ B9, bilirubin ≥3 mg/dl) or renal failure (creatinine ≥1.2 mg/dl or BUN ≥ 25 mg/dl or hyponatraemia ≤130 mEq/l). | 92% | A, 1 |

| When is it indicated to discontinue SBP prophylaxis? | SBP prophylaxis can be discontinued if ascites disappears without diuretics. | 82% | B, 1 |

| Recurrent and refractory ascites | |||

| Are there differences between refractory and recurrent ascites? | Recurrent ascites is a distinct entity from both diuretic-responsive ascites or uncomplicated ascites and refractory ascites, with different medium- and long-term prognoses. | 89% | C, 1 |

| Is short-term treatment with albumin indicated for bacterial infections other than SBP? | Treatment with albumin is not recommended in patients with cirrhosis and bacterial infections other than SBP. | 82% | B, 1 |

| Portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis | |||

| When is it indicated to anticoagulate a patient with cirrhosis and PVT? | Anticoagulation is indicated in all patients with cirrhosis and recent (<6 months) complete or partially occlusive (>50%) PVT, especially in patients who are candidates or on the waiting list for liver transplantation or those with symptomatic thrombosis. | 97% | B, 1 |

| How long should anticoagulation be maintained in a patient with cirrhosis and PVT? | Anticoagulation should be maintained for at least six months to achieve recanalisation. Once the portal vein has been recanalised, it is recommended to maintain anticoagulation in patients who are candidates for or on the transplant waiting list or in those who had symptoms of intestinal ischaemia during the acute episode. | 98% | B, 1 |

| Is it indicated to implant a TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and PVT? | TIPS is an option for portal vein recanalisation in patients with PVT, especially in those with complications of portal hypertension. | 83.3% | B, 1 |

| Is anticoagulation indicated for patients with cirrhosis and PVT who are candidates for liver transplantation? | Anticoagulation is indicated in all patients who are transplant candidates or on the transplant waiting list regardless of the severity or extent of thrombosis. | 80% | B, 1 |

| Refractory hepatic hydrothorax | |||

| Is it indicated to implant a TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and refractory hydrothorax? | In patients with refractory hepatic hydrothorax, TIPS can be considered on an individual basis. | 90% | C, 1 |

| Are patients with refractory hepatic hydrothorax candidates for liver transplantation? | The prognosis of patients with hepatic hydrothorax is worse than indicated by MELD and they should be assessed for liver transplantation. | 89% | C, 2 |

| Questions posed to the panel that did not reach consensus (<80%) | |||