The presence of digestive symptoms associated with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in remission is a topic of growing interest. Although there is heterogeneity in clinical studies regarding the use of IBD remission criteria and the diagnosis of IBS, the available data indicate that the IBD–IBS overlap would affect up to one third of patients in remission, and they agree on the finding of a negative impact on the mental health and quality of life of the individuals who suffer from it. The pathophysiological bases that would explain this potential overlap are not completely elucidated; however, an alteration in the gut-brain axis associated with an increase in intestinal permeability, neuroimmune activation and dysbiosis would be common to both conditions. The hypothesis of a new clinical entity or syndrome of “Irritable Inflammatory Bowel Disease” or “Post-inflammatory IBS” is the subject of intense investigation. The clinical approach is based on certifying the remission of IBD activity and ruling out other non-inflammatory causes of potentially treatable persistent functional digestive symptoms. In the case of symptoms associated with IBS and in the absence of sufficient evidence, comprehensive and personalized management of the clinical picture (dietary, pharmacological and psychotherapeutic measures) should be carried out, similar to a genuine IBS.

La presencia de síntomas digestivos asociados al síndrome de intestino irritable (SII) en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) en remisión es un tema de interés creciente. Si bien existe una heterogeneidad de los estudios clínicos en relación con el uso de criterios de remisión de la EII y del diagnóstico de SII, los datos disponibles indican que la superposición EII-SII afectaría hasta un tercio de los pacientes en remisión, y coinciden en el hallazgo de un impacto negativo en la salud mental y calidad de vida de los individuos que la padecen. Las bases fisiopatológicas que explicarían esta potencial superposición no están completamente dilucidadas, sin embargo, la alteración en el eje cerebro-intestino asociada al aumento en la permeabilidad intestinal, la activación neuroinmune y la disbiosis serían fenómenos comunes a ambas condiciones. La hipótesis de una nueva entidad clínica o síndrome de «enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal irritable» o «SII postinflamatorio» con un perfil de microinflamación distintivo del SII, es motivo de intensa investigación. El reto clínico supone certificar la remisión de la actividad de la EII y descartar otras causas no inflamatorias de síntomas digestivos funcionales persistentes potencialmente tratables. En el caso de síntomas asociados a SII, a falta de evidencia suficiente, se debe realizar un control integral y personalizado del cuadro clínico (medidas dietéticas, farmacológicas y psicoterapéuticas), similar a un SII genuino.

Inflammatory Bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are chronic diseases that affect the digestive tract, and present with fluctuating clinical activity, partly sharing their clinical symptoms (abdominal pain, bloating and diarrhoea). Despite these subtle similarities, they differ profoundly in the degree of involvement and level of inflammation present in the intestinal mucosa, clinical evolution and therapeutic strategies used in their management, among other things.1 However, some recent studies have suggested pathophysiological alterations that could be similar in both conditions. Among these are alterations in the brain-gut axis associated with increased intestinal permeability, neuroimmune activation and dysbiosis.2 The idea put forward that IBS could be considered an incipient or mild manifestation of IBD has been contested due to the lack of evidence to demonstrate this sequence. However, the coexistence of IBD with IBS in patients in remission has been a reason for clinical and scientific interest due to the difficulties of establishing their diagnosis.1,2 The objective of this article is to provide a review of the available evidence on the relationship between IBD and IBS that makes it possible to explain the existence of persistent digestive symptoms in a subgroup of patients with IBD in remission.

Overview of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Making a counterpointIBD, with its main exponents, ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), is characterised by periods of clinical activity (flare-ups) and remission of the disease, and can also be accompanied by extraintestinal manifestations.3 Its prevalence and incidence increase with the industrialisation of countries and urban life, being higher in Western countries. Its maximum incidence is in adults between 20 and 30 years old, without significant differences by sex.4 Its diagnosis is established with the set of clinical symptoms (abdominal pain, diarrhoea, rectal bleeding) and endoscopic, histological and/or radiological studies that show intestinal inflammation.3 In its pathophysiology, development and evolution, there is a marked interaction of genetic factors, intestinal microbiota, immune response and environmental factors.3

IBS, for its part, is a digestive disorder that is common around the world, both in urban and rural areas, reaching a prevalence of 12.8%–15% in the general population, being more frequent in women, with a higher presentation among those from 30 to 50 years of age.5 Its diagnostic criteria, based on the Rome IV consensus, are established as the presence of abdominal pain and alterations in bowel habits.6 Similar to IBD, the pathophysiology of IBS is complex and multifactorial, involving environmental and psychosocial factors that lead to alterations in gastrointestinal motility, visceral hyperalgesia, increased intestinal permeability, immune activation and alteration of the microbiota, which reflects impaired communication along the brain-gut axis.7 It should be noted that, unlike IBD, a genetic factor has not been fully established.3 In contrast to IBD, the results of routine clinical, laboratory, endoscopic and radiological tests show the absence of intestinal inflammation.6 However, through analytical laboratory research techniques, findings associated with microinflammation in the intestinal mucosa and plasma have been described in subgroups of patients with IBS, with evidence of hyperplasia and activation of immune cells (increase in mast cells, eosinophils, T cells and plasma cells) both in small intestine and colonic biopsies, as well as elevated levels of systemic pro-inflammatory cytokines.8 This state of microinflammation, also called by some authors “low-grade immune activation”, suggests the possibility that this condition corresponds to a mild or initial form of IBD, a controversial hypothesis if we consider the current evidence that indicates that the natural evolution of IBS does not lead to the development of IBD.6 However, the existence of persistent digestive symptoms, either isolated or associated, is common in the course of inactive IBD. It has been described that up to a third of patients with IBD in remission have IBS-like symptoms,9 its prevalence being even higher than that described in the general population,9–17 and higher for CD than for UC.11,18,19 This debatable relationship between IBS symptoms in patients with IBD in remission leads us to wonder if IBS is a pre-existing or de novo condition triggered by high levels of psychosocial stress in patients with IBD, or if they are simply independent conditions that coexist by coincidence, considering the high prevalence of IBS in the general population, or if its appearance is the consequence of a post-inflammatory sequela of the mucosa that led to chronic microstructural and functional changes, or if these symptoms correspond to minimal IBD activity not detected by conventional methods. The answers to these questions have not yet been clarified.

Developing evidence. Studies on inflammatory bowel disease-irritable bowel syndrome overlapThe first data on IBS post-IBD was described in 1983 by Isgar et al., who studied 98 patients with UC in clinical and endoscopic remission, reporting that 33% of them had IBS-type symptoms according to Manning’s criteria.9 Subsequent studies have shown similar overlap results,12,13,16,17 and others have documented lower prevalences of IBS symptoms in IBD, in the range of 16.3% to 27%.14,18–20 Along these lines, a meta-analysis that included 13 studies with 1703 patients with IBD showed that IBS-type symptoms were present in 35% of patients with IBD in remission (OR 4.39 for IBS), being more frequent in CD (46%) vs. UC (36%) (OR 1.62).11 For their part, Simren et al. did not observe a relationship between the presence or absence of IBS-like symptoms in IBD associated with age, the use of chronic treatment for IBD and the extent of the disease, both in UC and CD. However, they found that the duration of IBD was longer in the group with IBS symptoms than in those without associated symptoms (22 vs. 18 years, p = 0.06).10 In agreement with this finding, a study of a cohort of patients with UC reported that IBS-like symptoms were more frequent after 20 years of the disease.15 The latter data, although limited, would suggest that inflammation sustained over time and structural damage caused by fibrosis may lead to changes in bowel function in a subgroup of patients with IBD.21,22

Difficulties in the diagnostic criteria for inflammatory bowel disease-irritable bowel syndrome overlapOne of the main problems in establishing the coexistence of IBS with IBD is the heterogeneity between the study designs regarding the criteria selected by the authors to define remission of IBD and the diagnosis of IBS (Manning criteria, Rome I, II, III or recently IV).6 In relation to the remission of IBD, while some researchers base their work on clinical criteria,17 others use endoscopic and/or histological remission criteria.13,16 Other authors use non-invasive biomarkers, such as faecal calprotectin (FC) to define remission, although with different cut-off points.12,19 Some of these variables are discussed below:

Use of clinical indices or symptom surveys: a lack of correlation has been demonstrated between symptoms and IBD activity.23 Thus one study reported that 27% of UC patients in endoscopic and histological remission maintained an alteration in stool frequency.24 From a clinical point of view, the limited variety of symptoms offered by the digestive tract can make it difficult to differentiate an IBD outbreak from a case of IBS, which can lead to errors in its control or treatment, increased morbidity as a result of adverse reactions due to overtreatment, deterioration in quality of life and increased health costs.

Use of biomarkers: FC, a biomarker of intestinal inflammatory activity, has been widely used for the differential diagnosis of IBD with functional diseases such as IBS, and to evaluate the response to treatment and monitoring of IBD.25 FC has a good correlation with endoscopic activity, with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 73%, with better performance for UC than for CD.26,27 Although the normal reference value to differentiate inflammatory from functional disease in the general population is <50 µg/g,28,29 in patients with IBD a meta-analysis that included 13 studies found that an FC value of 250 µg/g was able to discriminate between endoscopically active and inactive patients with a combined sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 82%.30 This cutoff limit has been rethought in response to new evidence and greater demands in the definition of remission. Thus, in relation to the search for histological remission, a prospective study in patients with UC showed that an FC value ≤40.5 µg/g predicted histological remission (area under the curve of 0.755; 41% sensitivity and 100% specificity).31 Currently, an FC value <100 µg/g is considered to be one of the treatment goals in IBD due to its ability to predict a low inflammatory activity in UC, allowing it to substitute even the endoscopic evaluation.32,33

Studies that use FC to assess overlap are heterogeneous and use different gold standards in the definitions of remission. Some of these studies have used FC < 250 µg/g to consider patients in remission,23,34 which could erroneously include a group of patients with subclinical and histological inflammation and overestimate the prevalence of IBS. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that FC values <50 µg/g, and even FC < 100 µg/g,33 could rule out subclinical inflammation as a cause of persistent functional symptoms in patients with IBD in remission, and FC values between 100 and 250 µg/g should require more attention, since they could reflect a need to optimise the treatment of IBD, and thereby provide symptomatic relief. On the other hand, elevated FC has not been demonstrated in patients with IBD in remission with IBS symptoms.12,18 In fact, Jonefjall et al. did not find differences in FC levels between those patients with IBD in deep remission with and without IBS-type symptoms (18 µg/g vs. 31 µg/g, p = 0.11), but they did detect higher levels of inflammatory cytokines.18 This suggests that FC levels of <50 µg/g, which might suggest the presence of IBS, would not be useful to discriminate hidden inflammation (“microinflammation”).

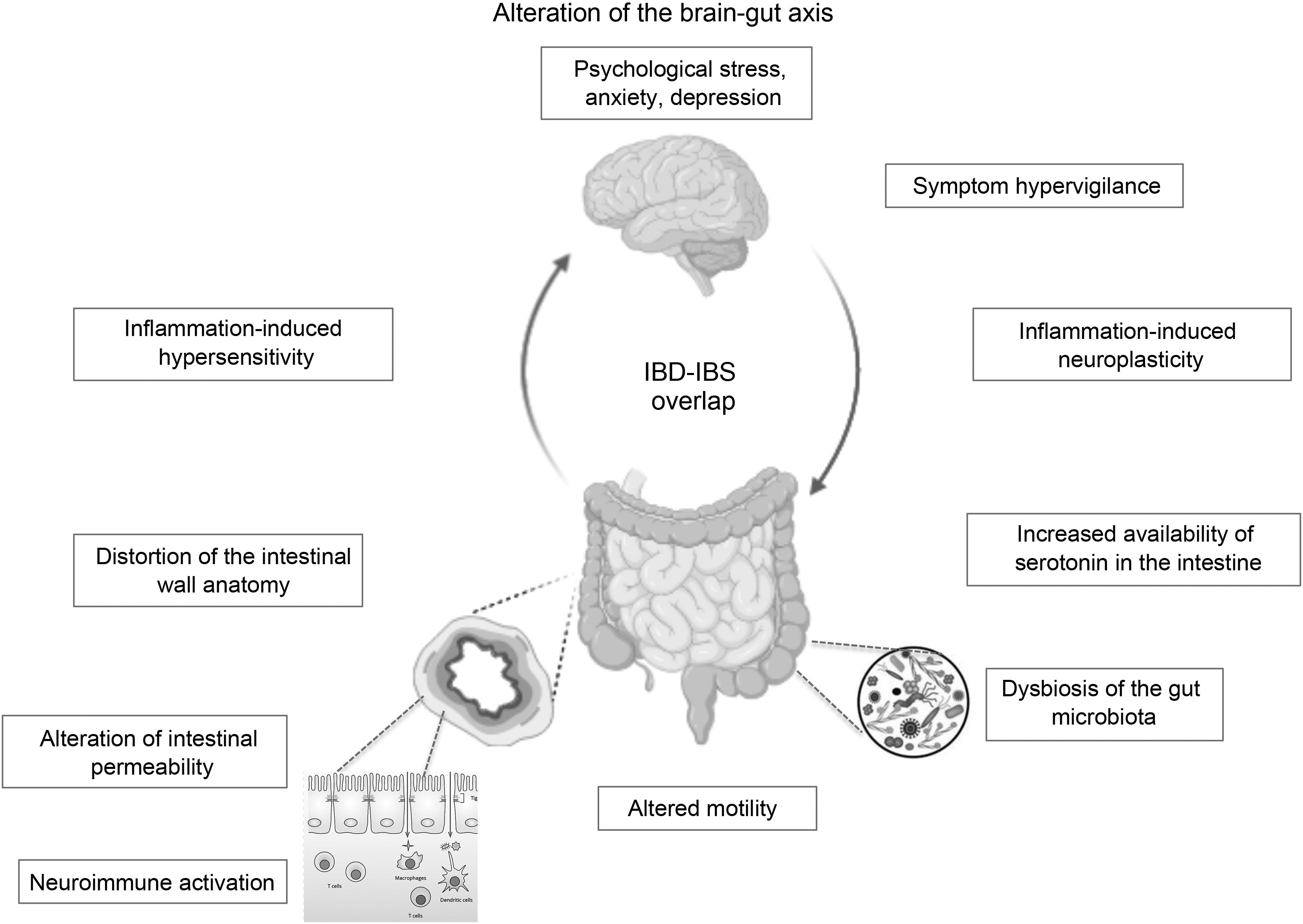

In the case of patients in endoscopic remission, a study in 103 patients with UC showed that the presence of histological activity would not necessarily explain the persistence of their functional symptoms, and the values of biomarkers such as FC and inflammatory cytokines did not differ between those with or without histological activity.24 It would appear that much more profound changes in the structure and function of the intestinal barrier secondary to chronic inflammation and not detectable by conventional studies could explain these IBS-like symptoms. An alteration at the level of the brain-gut axis would be a model proposed by some authors to explain the IBD–IBS overlap: organic disorders present in IBD such as alterations in the intestinal microbiota and in the permeability of the mucosa with subsequent translocation of macromolecules, bacteria and inflammatory cells would promote the development of visceral hypersensitivity that, combined with central factors such as anxiety and hypervigilance, would produce IBS-like symptoms in a subgroup of patients with IBD in remission.35

Below we will review some pathophysiological aspects that seek to elucidate the possible interaction between these two diseases.

Pathophysiological aspects of the interaction between inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndromeFrom a pathophysiological point of view, the condition that is closest to IBS-IBD overlap is post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS). This is characterised by the appearance of IBS symptoms after acute infectious gastroenteritis in previously asymptomatic individuals.36 It is postulated that the acquisition of an acute infection of the intestinal tract would generate a chronic inflammatory state in a subject with known risk factors (female sex, advanced age, psychological comorbidity – hypochondriasis, depression, neuroticism, stress, adverse life events – and smoking) and that it can remain even after eradication of the infectious agent.36 It has been observed that the colorectal mucosa of patients with PI-IBS presents a greater infiltration of macrophages, mast cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes, due to increased intestinal permeability in a genetically predisposed subject, unable to completely resolve the acute inflammation.37 This clinical picture gives us a glimpse of the effect that inflammatory damage could have over time in the intestinal mucosa of patients with IBD in remission with a certain risk profile for the development of functional symptoms.

Role of inflammation and cytokine profile in inflammatory bowel disease-irritable bowel syndromeIn the pathogenesis of IBD, an increase in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines has been described, which are key in the onset and evolution of the disease. Some of these are interleukins (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α.4 In relation to IBS, the results are contradictory38, but a trend has been described in subgroups of patients towards elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in plasma, mainly IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α.39,40

In relation to the IBS-IBD interaction, it has been postulated that the presence of persistent microinflammation in IBD in remission would contribute to alterations in the permeability of the intestinal epithelial barrier in a similar way to that observed in patients with IBS.41 A study that included 298 patients with UC found that 24 patients in deep remission with symptoms associated with IBS had significantly higher levels of some serum cytokines (IL-1b, IL-6, IL-13, IL-10 and IL-8) compared with asymptomatic UC patients in remission, in addition to higher levels of anxiety, depression and perception of stress.18 However, in a recent study that defined the profile of systemic inflammatory proteins, distinctive profiles were observed in patients with UC and IBS, regardless of UC inflammation or the presence of IBS-like symptoms in those with UC in remission, which suggests that the inflammatory mechanisms of these diseases may be different.42

Role of inflammation and disruption of the epithelial barrier, mast cells and eosinophilsDisruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier has been described both in patients with IBD43 and with IBS.44,45 Vivinus-Nébot et al. demonstrated an increase in paracellular permeability using the Ussing chamber, and a decrease in the mRNA expression of tight junction proteins (zonula occludens-1, α-catenin and occludin) in caecal biopsies of patients with IBD in remission with IBS-like symptoms, and in patients with IBS in comparison with those with IBD in remission without symptoms (p < 0.01), and controls (p < 0.01). Furthermore, a significant increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes and TNF-α expression was documented in biopsies … of patients … with IBD and IBS-like symptoms, findings that were not observed in biopsies of patients with IBS.13 Does this then mean that the overlapping of IBS symptoms in IBD represents a different clinical picture from classic IBS? No doubt more studies are needed to confirm these results. Subsequently, a prospective study in which the permeability of the intestinal mucosa was evaluated using confocal laser endomicroscopy (quantified by Confocal Leak Score [CLS]) in patients with IBD in endoscopic remission, a higher CLS score was observed (indicative of greater permeability) in symptomatic patients (diarrhoea, abdominal pain) than in asymptomatic patients (p < 0.001) and controls (p < 0.001), correlated with a greater severity of diarrhoea. Interestingly, in this study, intestinal permeability was similar for control subjects and those with asymptomatic inactive IBD. However, the absence of a control group with IBS could limit the validity of these observations.20 Along these lines, Katinios et al. observed a higher paracellular permeability of the intestinal epithelium in colonic biopsies of patients with inactive UC (clinical-endoscopic remission) and in patients with mixed subtype IBS, compared to control subjects (p < 0.05), with this being higher for UC. These results were significantly correlated with the number of eosinophils in the tissue, this correlation being higher for UC than for IBS (p < 0.05).41 It should be noted that, in this study, patients with UC had recently been treated for relapse within the year, which could explain the existence of greater permeability of the intestinal epithelium despite remission, different from that previously reported in UC in prolonged remission.20,46 However, the authors suggest that increased paracellular permeability may be a typical pathophysiological feature for both diseases.41

The mast cell is an immune cell that has been involved in the regulation of intestinal permeability in both IBD47 and IBS.48 A close interaction between eosinophils and mast cells has been described in IBD that could be associated with a disruption of the intestinal barrier and increased permeability.41 Recently, a study that included 35 patients with IBD (15 UC and 20 CD), in deep remission with IBS symptoms, reported an increase in the number of eosinophils in the colonic mucosa compared to patients in remission without IBS symptoms (average 421 eo/mm2 in UC, 397 eo/mm2 in CD vs. 36 eo/mm2 in controls) and, when treated with a hypoallergenic diet (elimination of five foods) and oral budesonide, a decrease was observed in the number of eosinophils associated with a favourable clinical response in 67% of the patients at 7–10 days.49 The authors outlined which allergenic foods could trigger an immune response in a previously altered mucosa, and thus explain the symptoms present in patients with IBD in remission. Despite the suggestive nature of these results, they should be taken with caution, since they do not match what was reported in previous studies in patients with active IBD, which described a much smaller increase in the number of eosinophils,50,51 and may only reflect an increased eosinophil response in a subgroup of IBD patients.

Inflammation-induced visceral hypersensitivityThe transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) is expressed in primary afferent neurons that sense the pain stimulus, and its expression levels have been related to the visceral hypersensitivity described in some gastrointestinal disorders.52,53 Similar to what was seen in a small group of patients with IBS,54 the same author, in a study of colonic biopsies of 20 patients with quiescent IBD (deep remission) with IBS-like symptoms, found a 3.9-fold increase in immunoreactive nerve fibres of TRPV1 compared to controls, and five times more than in asymptomatic quiescent IBD patients, which was correlated with the severity of abdominal pain.55 Given the small number of patients in these studies, it is still premature to assert a role for TRPV1-mediated visceral hypersensitivity in the pathophysiology of pain in IBD in remission. Its confirmation could lead to a potential therapeutic target.

Alterations in intestinal motilityColonic motility studies in patients with IBD are limited and with differing results due to the fact that they have been conducted in a small number of patients, in vivo vs. in vitro, UC vs. CD, with different disease states (active vs. inactive IBD, disease extension and time of evolution) and different diagnostic techniques. In view of these considerations, some studies have shown alterations in colonic motility in subgroups of patients with UC and CD.56 One mechanism postulated is that chronic inflammation may produce changes in the neuronal interaction of the enteric nervous system, which could persist over time after the inflammatory damage resolved. This is known as “inflammation-induced neuroplasticity”, and considers the hyperexcitability of afferent neurons, synaptic facilitation and the attenuation of inhibitory neuromuscular transmission.57 Other alterations described in small groups of patients with IBD, and that may be induced by chronic inflammation, are changes in ionic conductance in smooth muscle,58 the response to neurotransmitters and the greater availability of serotonin in the inflamed regions secondary to changes in signalling in the intestinal mucosa.59 It is postulated that distortion of the intestinal wall anatomy that includes mucosal atrophy, muscle changes (fibromuscular dysplasia of the mucosa and muscularis propria) and the development of fibrosis, both in CD and UC, would lead to stiffness of the intestinal wall, colonic dysmotility and anorectal dysfunction.56 However, other authors have not been able to demonstrate colonic dysmotility in patients with IBD.60

Undoubtedly, the theory that inflammation-induced neuroplasticity, the development of fibrosis and secondary dysmotility could partly explain the presence of persistent functional symptoms in patients with IBD in remission is very provocative but, given the limited evidence and controversial results, this cannot be extrapolated to the entire population of IBD patients.

Role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease-irritable bowel syndromeThe role of the gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of IBS and IBD is known. Patients with IBD show a dysbiosis characterised by a decrease in the diversity of the microbiota (decrease in Firmicutes), a reduction in bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids (Clostridium cluster iv, XIVa, XVII and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii), and an increase in mucolytic bacteria (Ruminococcus gnavas and Ruminococcus torques), sulfate-reducing bacteria (Desulfovibrio) and pathogenic bacteria (adhesive/invasive E. coli).61 In IBS, in turn, there is solid evidence of these alterations in microbial composition and density, where a relative abundance of pro-inflammatory bacteria species (Enterobacteriaceae) has been described, with a reduction in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, in addition to changes in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio compared to healthy controls.62

A study that analysed the composition of the faecal microbiota by determining 16S rRNA revealed that the presence of IBS-like symptoms in patients with IBD in remission (defined by FC < 250 µg/g) was not associated with distinctive alterations related to the abundance of the individual bacterial taxa or in the global bacterial diversity with respect to patients with asymptomatic IBD in remission, active IBD and IBD with occult inflammation (asymptomatic IBD patients with FC > 250 µg/g). However, this study did not consider healthy controls and subjects with IBS for comparison.34 Recently, after analysing biopsies of patients with CD and controls, Boland et al. reported that, despite the evidence of remission, the diversity was lower in the intestinal microbiota in CD than in controls, in addition to finding a reduced Chao1 diversity (p = 0.01) and a greater tendency to dysbiosis in the intestinal microbiota of patients with residual symptoms (p = 0.059), indicating that its composition may be associated with persistent diarrhoea.63

Psychological aspects and quality of lifePsychosocial factors are strongly involved in the pathophysiology of IBS and constitute one of the components of the interaction of the brain-gut axis. Psychiatric comorbidity is common in IBS, with prevalence of anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorder of 39.1% and 23%, respectively, and of symptoms of depression and depressive disorder of 28.8% and 23.3%.64 Similarly, depression affects more than 25% of patients with IBD, and anxiety more than 30%, being greater in active than in inactive IBD,65 and two to three times greater than in the general population,66 contributing to a deterioration in the quality of life of patients. The influence of psychosocial stress on the inflammatory activity of IBD is a matter of discussion,67 but new evidence has described a possible role of stressful events as triggers of IBD flare-ups.68

Similar to that reported by other authors12 in studies of IBD–IBS overlap and psychological impact, Perera et al. described higher levels of anxiety and depression in IBD patients in remission with IBS symptoms compared to those without symptoms.16 Furthermore, a recent study of 137 patients with IBD showed a significantly lower IBDQ (IBD quality of life) score in those patients in remission with IBS-like symptoms.17 Another study showed similar findings, in addition to higher levels of depression, anxiety and somatisation in patients with IBD in remission (FC < 250 µg/g) with IBS-like symptoms, maintaining this trend when using FC values <100 µg/g to define remission.19 Supporting these data, in a cross-sectional study that included 6309 subjects with IBD, 20% reported being diagnosed with IBS associated with IBD, with worse quality of life (IBDQ) indices found in this group, as well as greater association with anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbances, pain interference and decreased social satisfaction, compared to those with IBS.69

It is not clear whether higher levels of anxiety and depression are a risk factor or a consequence of the presence of IBS symptoms in patients with IBD in remission. Nevertheless, the deterioration in quality of life is significant in this subgroup of patients.70

The brain-gut axis is the neuroanatomical substrate for bidirectional interaction between the neuroendocrine pathways, the central nervous system, the peripheral nervous system and the autonomic nervous system with the digestive tract. Psychological disorders and psychosocial factors influence the functioning of the digestive tract, generating symptoms that, in turn, generate greater psychological distress.7,70,71 Although this is one of the pillars for understanding IBS, it could partly explain the IBS-IBD overlap in predisposed individuals. As previously mentioned, it is not known whether psychological disorders, highly prevalent in IBD patients in remission with IBS-like symptoms, are caused by persistent digestive symptoms or are a predisposing factor for their development. Some authors suggest that the presence of IBS symptoms in IBD in remission could correspond to a syndrome other than classic IBS, since it would occur in patients with an inflammatory basis. Some … of the current evidence has shown alterations in intestinal permeability and mild inflammatory activation that are different or not seen in genuine IBS or in asymptomatic patients with IBD in remission. These alterations, … based on the brain-gut axis interaction, could be triggered by psychological distress. Gajula et al. have proposed calling this syndrome “irritable inflammatory bowel disease”.72 Undoubtedly, more studies are needed to clarify and confirm this IBS-IBD relationship through prospective studies that make it possible to assess which profile of patients with IBD will be more likely to develop “post-inflammatory IBS” (Fig. 1).

Despite this approach, in view of the current limited evidence, it has until now seemed more reasonable and conciliatory to speak of the “coexistence” of both diseases (IBS-IBD), which could occur independently in the same subject, either successively or simultaneously, and whose clinical management should respond to the biopsychosocial model.

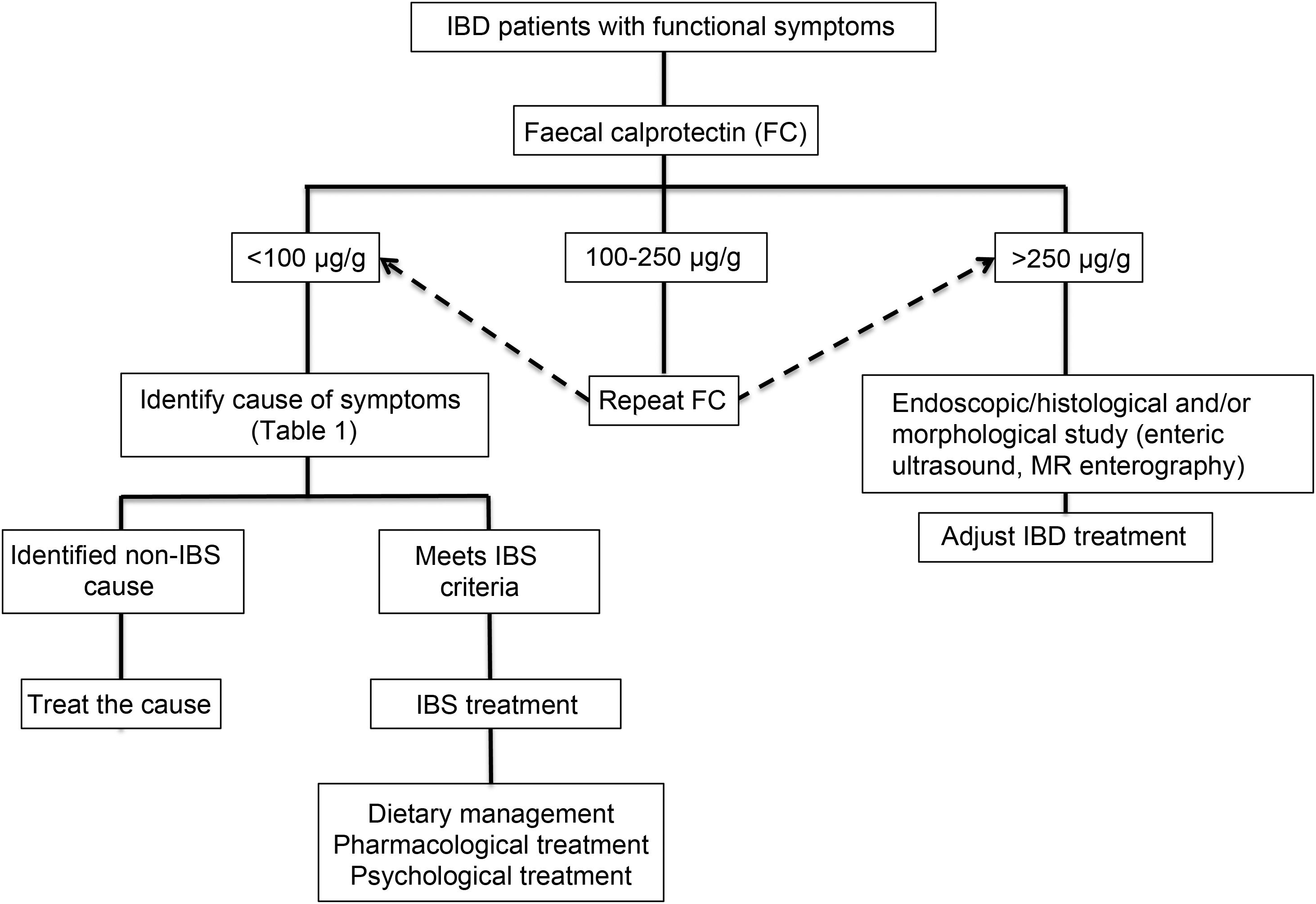

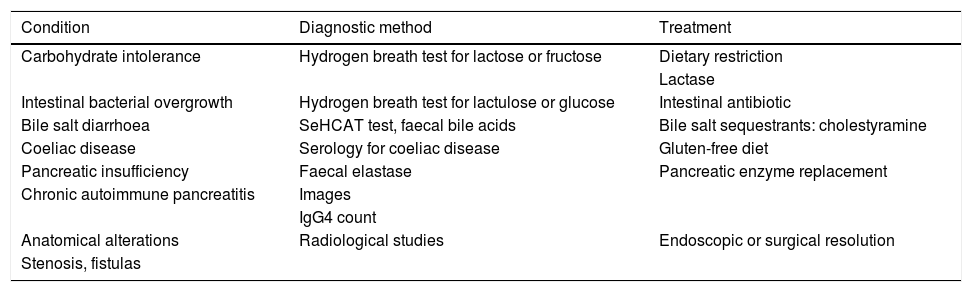

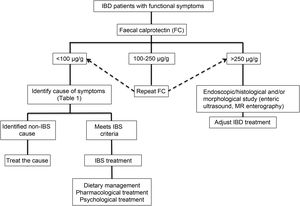

Clinical approachWhen dealing with patients with IBD in remission with IBS-like symptoms (alteration of bowel habit, whether diarrhoea or constipation, abdominal pain, bloating-distension), it is necessary to inquire about the presence of warning symptoms and signs … such as weight loss, bleeding, anaemia, fever or night-time symptoms. In addition, they should be questioned about the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, drugs that alter intestinal motility or a … recent gastrointestinal infection. The physical examination should be exhaustive with the search for alteration of vital signs, abdominal masses, increased abdominal rebound tenderness, pale skin or mucous membranes, among others. Warning signs or symptoms will require direct use of an endoscopic study and/or some imaging method. If this is not the case, biomarkers such as FC can be used as an initial non-invasive approach to confirm remission of IBD (Fig. 2).73 Although the limit values of FC can vary between CD and UC, it is recommended that, in the presence of intermediate values (that is between 100 and 250 µg/g), a follow-up is carried out at three months to confirm its elevation as a reflection of the activity of the disease, which could benefit from intensified IBD therapy. Faced with low FC values (FC < 100 µg/g), it is necessary to consider differential diagnoses that may explain the presence of digestive symptoms that will require a directed study (Table 1) before classifying the patient as a true IBS patient. In addition, an active investigation should be made of psychological distress or stressful events (using validated scales) that may be influencing the symptoms. Undoubtedly, we must consider other non-inflammatory complications typical of IBD as a generator of symptoms, such as the presence of stenosis in CD or UC, and fistulas, as well as postoperative sequelae such as the presence of adhesions or scarring. The imaging study should be directed according to clinical and laboratory findings.

Differential diagnosis of symptoms associated with irritable bowel syndrome in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission.

| Condition | Diagnostic method | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate intolerance | Hydrogen breath test for lactose or fructose | Dietary restriction |

| Lactase | ||

| Intestinal bacterial overgrowth | Hydrogen breath test for lactulose or glucose | Intestinal antibiotic |

| Bile salt diarrhoea | SeHCAT test, faecal bile acids | Bile salt sequestrants: cholestyramine |

| Coeliac disease | Serology for coeliac disease | Gluten-free diet |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | Faecal elastase | Pancreatic enzyme replacement |

| Chronic autoimmune pancreatitis | Images | |

| IgG4 count | ||

| Anatomical alterations | Radiological studies | Endoscopic or surgical resolution |

| Stenosis, fistulas |

SeHCAT: selenium-75 homocholic acid taurine.

Table adapted from Colombel et al.73

In the absence of prospective, randomised studies, if a probable coexistence of IBS-IBD is confirmed, treatment should be individualised and directed towards diet control and psychological and pharmacological therapy, according to the predominance of symptoms (analgesics, antispasmodics, antidepressants, probiotics, antidiarrhoeals and laxatives), similar to that for classic IBS. MODULATE, a prospective long-term follow-up study is currently underway that aims to evaluate the effectiveness of amitriptyline, ondansetron, loperamide and a low FODMAP diet in UC patients in remission with IBS-like symptoms.74 Recently, Cox et al. reported that 14/27 patients (52%) with IBD in remission improved their IBS-type symptoms after four weeks of a low FODMAP diet when compared with those with a control diet (p = 0.007), also improving their quality of life scores and finding less abundance of Bifidobacterium adolescentis, B. longum and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, without being able to demonstrate changes in inflammation markers.75 Studies in this line and with a greater number of patients are necessary to corroborate these results.

ConclusionIBS-like symptoms are frequent in patients with IBD in remission, which constitutes a clinical challenge due to the similarity of their symptoms. Although they are two different diseases that could coexist in the same patient, either due to the pre-existence of one or presenting simultaneously, it is interesting to consider that their pathophysiological mechanisms have some similarities: neuroimmune activation, alterations in the permeability of the intestinal wall and in the intestinal microbiota common to both could converge in an alteration of the brain-gut axis (Fig. 1), with a microinflammation profile different from that of genuine IBS or IBD in remission. This new syndromic concept of “post-inflammatory IBS” or “irritable inflammatory bowel disease” is tempting, but the scientific evidence is still insufficient to support this hypothesis. Confirmation of IBD remission is key to avoiding diagnostic and management errors with adverse events associated with unnecessary intensification of IBD therapy. The treatment of this condition is empirical, and is based on the body of evidence available on the biopsychosocial management of IBS, which could significantly improve the quality of life of these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors from the Hospital Clínico Universidad de Chile are grateful for the support and advice of the FONDECYT Project 1181699 in the article.

Please cite this article as: Pérez de Arce E, Quera R, Beltrán CJ, Madrid AM, Nos P. Síndrome de intestino irritable en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. ¿Sinergia en las alteraciones del eje cerebro-intestino? Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:66–76.