Casos Clínicos en Gastroenterología y Hepatología

More infoAcute pancreatitis is a complex disease with potentially severe and fatal outcome, in which pancreatic enzymes activation causes local pancreatic damage, resulting in an acute inflammatory response.1 The most common causes include biliary tract stones and alcohol abuse. Extrapancreatic fat necrosis (EXPN) has been included as a distinct criterion of moderately severe disease in the Revised Atlanta Classification (RAC).2 The pathophysiological mechanism suggested being responsible for EXPN is necrosis of peripancreatic fatty tissue. That is caused by pancreatic enzymes, resulting in the release of adipocytokines in blood.1,2

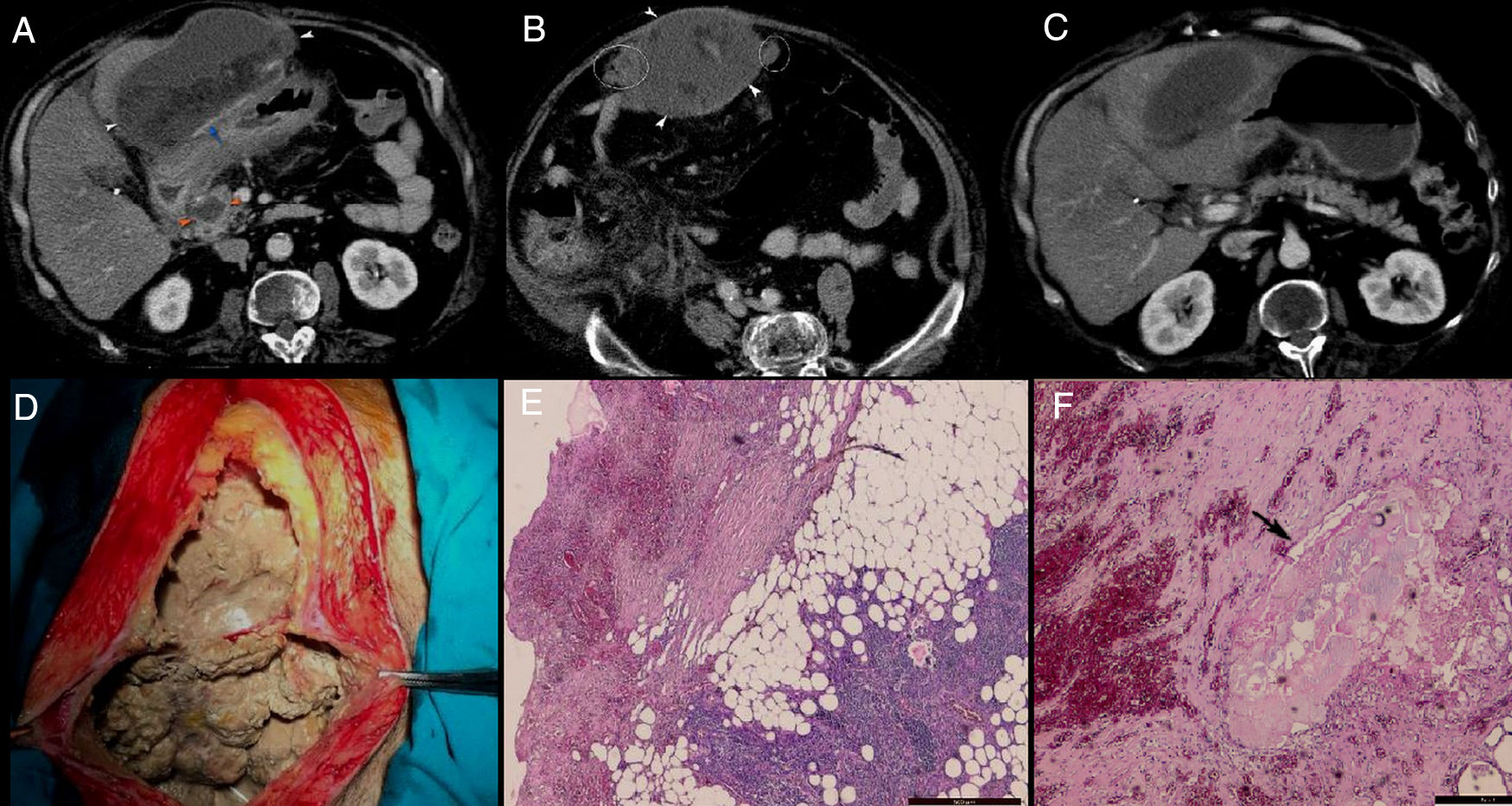

A 50-year-old male with history of alcohol abuse addressed to the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain, nausea, fever, chills and weight loss. The patient declared that the pain started two months ago, after an episode of alcohol abuse, which became more intense, sharp and unremitting in the last three days before presentation. Pain has not been relieved by any analgesics or antispasmodic medications. Also, he complained of episodic nausea and vomiting, but denied hematemesis or diarrhoea. The patient had unintentionally lost 10kg in the last 2 weeks. Upon physical examination, he was febrile, with a temperature of 38.1°C, had severe epigastric sensitivity and abdominal rigidity. Blood examination showed findings of inflammation (white blood cell count, 20,240/μL with 87.5% neutrophils; C – reactive protein (CRP), 13.48mg/dL), hypoproteinemia (7.18g/dL), hypopotassemia (4.24mmol/L), hypocalcaemia (6.94mg/dL), respiratory alkalosis and metabolic acidosis. Liver tests were normal. Serum amylase and lipase levels were increased: 752IU/L (normal ref: 20–160) and 1026IU/L (normal ref: 8–78), respectively. Previous medical history included cholecystectomy and an open surgery for incarcerated umbilical hernia. His medical family history was unremarkable. CECT (Fig. 1A–C) revealed a 10cm×14cm×17cm well-encapsulated, heterogeneous mass with areas of non-liquid (fat) densities located in the greater omentum. It was adherent to the anterior gastric wall and to the transverse colon, with mass effect on the latter. There was no evidence of calcifications within. The mass appeared to encase the mesenteric vessels and it was accompanied by the presence of multiple, smaller nodules localized at the level of greater omentum and anterior right lateroconal. The pancreatic parenchyma had a normal enhancement, without obvious glandular pancreatic necrosis, with the exception of the pancreatic head where a small pseudocyst (2cm×2.5cm) was observed. Also, a subtle increase in peripancreatic fat attenuation was found, that extended to the mesenteric root and right anterior pararenal compartment.

A–C: Axial plane CECT: well-encapsulated, heterogeneous mass with areas of non-liquid (fat) densities developed in the greater omentum, adherent to the anterior gastric wall (white arrowhead) and with some smaller arterial branches within (blue arrow); a small pseudocyst was seen in the pancreatic head (orange arrowhead) associated with subtle increase in perilesional fat attenuation; the rest of the pancreatic parenchyma has a normal enhancement, with no obvious glandular pancreatic necrosis; increase in fat attenuation was extending to the mesenteric root, right subhepatic space and right anterior pararenal compartment; the mass was accompanied by the presence of multiple, small nodules localized on the lateral sites of it (white rings). D: Intraoperative findings: large amount of necrotic material adherent to the abdominal wall. E and F: Histopathological findings: necrotic fat areas, a large numbers of shadowy outlines of fat cells accompanied by severe fibrosis, inflammatory reaction, foamy macrophages and small vessels; a small focus of saponification (black arrow) was seen surrounded by inflammatory reaction, fibrosis and some fat cells. H&E. Bar=500μm.

Because of lack of documented history of pancreatitis and imaging studies for comparison, a neoplastic aetiology was considered and open surgery was performed due to the concern for peritoneal liposarcoma. During surgery a large amount of necrotic material was found adherent to the abdominal wall, gastric wall and transverse mesocolon (Fig. 1D) and it was debrided. Multiple white, friable peritoneal small nodules that resembled with caseum were found; therefore surgeons raised suspicion of peritoneal tuberculosis. Due to the inflammatory changes developed between the transvers mesocolon and bowel loops, surgeons could not explore the entire peritoneal cavity. Adhesiolysis along with omentectomy were performed and samples were sent for microbiological examination. Ziehl-Neelsen staining and culture were both negative for B-Koch. The histological examination of the excised omentum revealed foci of shadowy outlines of fat cells with calcium deposits and foam cells (foamy macrophages) surrounded by inflammatory reactions and severe fibrosis (Fig. 1E and F); no malignant cells were found. We finally diagnosed this mass as extensive omental fat necrosis that occurred after an episode of alcohol-induced pancreatitis in the recent past. Unfortunately, after the surgery, patient's condition worsened, developed severe septic shock with metabolic acidosis, anuric renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and on day 3 postoperatively, the patient died.

RAC divided acute pancreatitis (AP) into two morphological types based on imaging appearance on CECT: acute interstitial pancreatitis (AIP) and acute necrotizing pancreatitis (ANP). ANP is subdivided into three forms: pancreatic parenchymal necrosis, extrapancreatic necrosis (EXPN), and combined necrosis.1 The diagnosis of EXPN was based on CECT criteria and was later confirmed intraoperatively (showing absence of pancreatic parenchymal necrosis).3 The pathophysiological mechanism suggested being responsible for EXPN is necrosis of peripancreatic fatty tissue (fat saponification) caused by pancreatic enzymes. Damaged pancreas releases lipolytic enzymes, which autodigest peripancreatic fat tissues.3 Macrophages and other inflammatory mediators are activated within the affected adipose tissue, leading to exacerbation of the inflammatory response. Triglycerides are released based on response of attack of phospholipases and proteases on fatty cell plasma membranes. Then the triglycerides are hydrolyzed and producing free fatty acids, which then avidly chelate the salts and precipitate to produce detergents (calcium depositions=soapy deposits in the tissues). This process causes reduction of total serum calcium that often occurs in cases of severe pancreatitis.4 After resolution of the acute exudate and ascites after an episode of pancreatitis, scattered nodules of fat necrosis may be seen on CECT throughout the retroperitoneum and abdominal cavity, which may seem like a “cluster of grapes” in “limited” forms, mimicking peritoneal carcinomatosis or like a heterogeneous mass in “extensive” forms, mimicking some peritoneal masses. These nodules may cause mass effect on the adjacent structures and exhibit delayed contrast enhancement, possibly as a result of the slow diffusion of contrast material through small capillaries in granulation tissue.5 Macroscopically, in”limited“forms, they appear like multiple white, friable peritoneal small nodules due to calcium deposition (saponification of fat).3,5 RAC refers to EXPN as “heterogenous collections with areas of fat surrounded by fluid density and areas with a slightly greater attenuation than seen in collections without necrosis.”.1 Koutroumpakis et al.3 have defined EXPN based on CECT findings as “nonliquefied, ill-defined, nodular areas of increased peripancreatic fat attenuation, with visual density higher than simple fluid or stranding, or as peripancreatic necrotic fluid collection in the absence of pancreatic necrosis”. The most common sites of EXPN are the lesser sac and the left anterior pararenal space. The larger collections can extend retroperitoneally over the psoas muscles to enter the pelvis, posterior pararenal space, perirenal space, transverse mesocolon, and small bowel mesentery.

EXPN may cause diagnostic dilemma and should be considered as differential diagnosis in appropriate clinical setting. CT findings of these lesions can be challenging to radiologists in lack of clinical data or previous imaging series for comparison. An awareness of the CECT features and evolutional appearance in these lesions may help to ensure a correct diagnosis and to avoid a misdiagnosis. That it is very essential because acute pancreatitis has a potentially severe to fatal outcome and extensive EXPN was frequently associated with organ failure and a prolonged clinical course.