Extraintestinal manifestations, in general, and in particular arthropathies, are a common problem in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. In fact, the relationship between those 2 entities is close and there are increasingly more data which suggest that the bowel plays a significant role in the aetiopathogenesis of spondyloarthritis. The association of inflammatory bowel disease with any kind of spondyloarthritis represents a challenging clinical scenario. It is therefore necessary that both gastroenterologists and rheumatologists work together and establish a fluent communication that enables the patient to receive the most appropriate treatment for each specific situation. The aim of this review is to make some recommendations about the treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and associated spondyloarthritis, in each different clinical scenario.

Las manifestaciones extraintestinales en general, y entre ellas las articulares en particular, suponen un problema frecuente en los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. De hecho, la relación entre ambas entidades parece estrecha y cada vez hay más datos que sugieren que el intestino desempeña un importante papel en la patogenia de las espondiloartritis. La asociación de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal con algún tipo de espondiloartritis supone un escenario clínico complejo. Es necesario, por tanto, que gastroenterólogos y reumatólogos puedan trabajar juntos y establecer una comunicación fluida que permita a cada paciente recibir el tratamiento más adecuado para cada situación concreta. El objetivo de esta revisión es el de establecer unas recomendaciones sobre el tratamiento de los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal y espondiloartritis asociada, en cada uno de los distintos escenarios clínicos.

The association between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and different joint manifestations has been known for several decades, although it was not until the end of the 1990s that the characteristic pattern of joint involvement in IBD was described.1 The growing knowledge of the closest inflammatory mechanisms shared by intestinal and joint involvement has favoured a better understanding of the inflammatory problem as something systemic and the adoption of common therapeutic strategies to address patients that are increasingly more complex. Consequently, the number of patients who gastroenterologists and rheumatologists must manage jointly in daily clinical practice is increasing; thus, the knowledge each specialist has regarding the other side of the disease and the coordination of therapeutic efforts must similarly increase.

In spite of the fact that every day we have more evidence of the correlation between the intestine and joints, whether linked to the role of the intestinal microbiota or other shared immunopathogenic or genetic mechanisms,2 we still do not have reliable tools that allow identification of those patients who are more prone to presenting both diseases, especially in cases where no clear clinical picture exists advising the referral.3 The interpretation of the different clinical situations in which each of the diseases is found, including the assessment of the inflammatory activity of each one, frequently represents a challenge for the other party. Consequently, it is very possible that there are a high number of patients who have not received an adequate diagnosis or treatment and who may end up suffering from disability and deterioration in quality of life.4,5 Consequently, fluid cooperation and communication between gastroenterologists and rheumatologists is fundamental for the approach and treatment of these patients.

The objective of this document is to guide the joint management between rheumatologists and gastroenterologists for the treatment of patients with IBD-associated spondyloarthritis (SpA)

Classification of the joint manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseaseClassically, it is considered that at least one third of patients with IBD present musculoskeletal manifestations which are classified within a group of rheumatological diseases known as SpA.

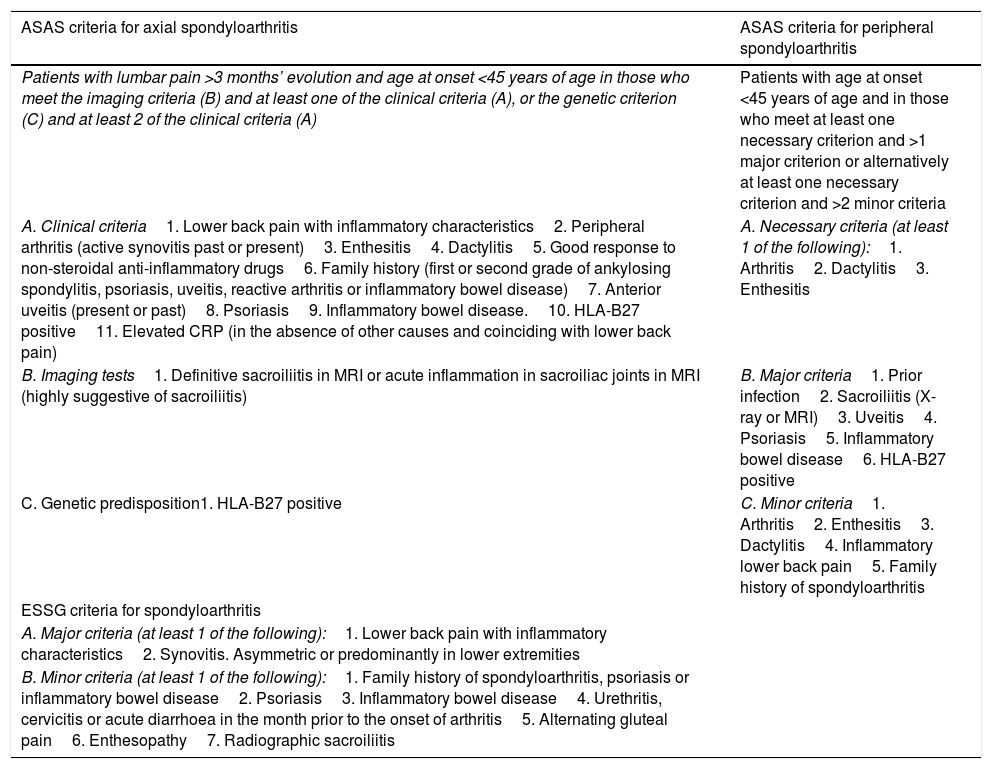

Currently, there are no validated criteria for the diagnosis of IBD-associated SpA, hence the criteria of the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) or of the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) are usually used. These are shown in Table 1. For practical purposes, these criteria are summarised in the presence of inflammatory back pain, arthritis, enthesitis or dactylitis in a patient who presents Crohn's disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC).6–9

Criteria for the diagnosis and classification of spondyloarthritis.

| ASAS criteria for axial spondyloarthritis | ASAS criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis |

|---|---|

| Patients with lumbar pain >3 months’ evolution and age at onset <45 years of age in those who meet the imaging criteria (B) and at least one of the clinical criteria (A), or the genetic criterion (C) and at least 2 of the clinical criteria (A) | Patients with age at onset <45 years of age and in those who meet at least one necessary criterion and >1 major criterion or alternatively at least one necessary criterion and >2 minor criteria |

| A. Clinical criteria1. Lower back pain with inflammatory characteristics2. Peripheral arthritis (active synovitis past or present)3. Enthesitis4. Dactylitis5. Good response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs6. Family history (first or second grade of ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, uveitis, reactive arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease)7. Anterior uveitis (present or past)8. Psoriasis9. Inflammatory bowel disease.10. HLA-B27 positive11. Elevated CRP (in the absence of other causes and coinciding with lower back pain) | A. Necessary criteria (at least 1 of the following):1. Arthritis2. Dactylitis3. Enthesitis |

| B. Imaging tests1. Definitive sacroiliitis in MRI or acute inflammation in sacroiliac joints in MRI (highly suggestive of sacroiliitis) | B. Major criteria1. Prior infection2. Sacroiliitis (X-ray or MRI)3. Uveitis4. Psoriasis5. Inflammatory bowel disease6. HLA-B27 positive |

| C. Genetic predisposition1. HLA-B27 positive | C. Minor criteria1. Arthritis2. Enthesitis3. Dactylitis4. Inflammatory lower back pain5. Family history of spondyloarthritis |

| ESSG criteria for spondyloarthritis | |

| A. Major criteria (at least 1 of the following):1. Lower back pain with inflammatory characteristics2. Synovitis. Asymmetric or predominantly in lower extremities | |

| B. Minor criteria (at least 1 of the following):1. Family history of spondyloarthritis, psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease2. Psoriasis3. Inflammatory bowel disease4. Urethritis, cervicitis or acute diarrhoea in the month prior to the onset of arthritis5. Alternating gluteal pain6. Enthesopathy7. Radiographic sacroiliitis |

CRP, C-reactive protein; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; X-ray, plain X-ray.

According to the clinical presentation, patients with SpA can be classified into two large groups: symptoms that are predominantly peripheral (pSpA), which can include arthritis, enthesitis or dactylitis, or axial (axSpA),10,11 although both patterns can coexist in the same patient and can be associated with other extra-articular manifestations, in particular uveitis. Typically, up to 10% of patients have skin involvement that can include erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum or aphthous stomatitis.1,6–8

Axial involvementAxial involvement is characterised by the presence of sacroiliitis, frequently asymmetrical, with or without concomitant vertebral involvement. According to the most up-to-date concepts (Table 1), axSpA includes a spectrum of entities from ankylosing spondylitis to non-radiographic axSpA. In general, it is not considered to be related to intestinal activity.6,8,12 The prevalence of axSpA has increased in recent years with the updating of diagnostic criteria which include early diagnosis of sacroiliac involvement by magnetic resonance imaging.7

Peripheral arthritisGenerally, this has a non-erosive and non-deforming progression. The main clinical characteristic of pSpA is the presence of arthritis, dactylitis or enthesitis (Table 1) and typically most commonly affects lower-limb joints.13–15 Two different patterns are recognised, although on occasion they can coexist in the same patient6,8,12,16:

- a.

Oligoarthritis or type II (involvement of at least five joints): usually with an acute course, starting within 24-48 hours and often coinciding with the intestinal activity of the disease, especially in UC. It particularly affects the large joints, generally in the lower limbs and with an asymmetric distribution. It is usually self-limiting and presents a good response to treatment with corticosteroids, although it can become chronic in up to 10% of cases.

- b.

Polyarthritis or type II (involvement of five or more joints): tends to have a consistent course; traditionally, it is considered to be separate from the intestinal inflammatory activity of the disease and can progress to chronic forms in around 40% of cases.

Some of the drugs used in the treatment of IBD may produce side effects involving the joints and these should be differentiated from those associated with SpA. The most important are those caused by corticosteroids (including osteoporosis or avascular bone necrosis) or thiopurines.16

Moreover, the onset of lupus induced by biological therapies against tumour necrosis factor α (anti-TNF-α) is not a common problem (0.1%), although the prevalence of conversion to positive of antinuclear antibodies can reach up to 40%. Similar symptoms associated with sulfasalazine or mesalazine have also been reported.9 Furthermore, cases of arthralgia, or even arthritis or sacroiliitis, associated with treatment with vedolizumab have been reported, which can affect up to 3-5% of patients in some clinical practice series.17–19

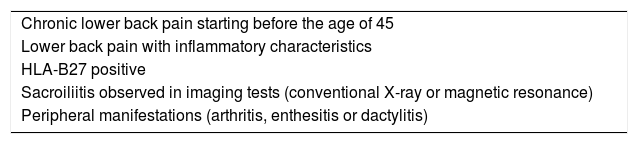

Diagnostic process in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease and arthralgiaThere are no validated criteria for referral from Gastroenterology to Rheumatology for patients with IBD and osteoarticular symptoms. Consequently, in general, and given the considerable heterogeneity and frequency of joint symptoms in patients with IBD, the presence of arthralgia could make assessment by Rheumatology reasonable. Recommendations of a panel of ASAS experts have recently been published regarding the referral of patients with suspected axSpA from any setting and for their assessment by a rheumatologist, although these recommendations are still to be validated in clinical practice.20 In Spain, the Sociedad Española de Reumatología [Spanish Society of Rheumatology] and the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] have agreed on certain referral criteria3 which are pending validation in a prospective study in progress. These criteria are summarised in Table 2.

Criteria for the referral of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and arthralgia to Rheumatology.a

| Chronic lower back pain starting before the age of 45 |

| Lower back pain with inflammatory characteristics |

| HLA-B27 positive |

| Sacroiliitis observed in imaging tests (conventional X-ray or magnetic resonance) |

| Peripheral manifestations (arthritis, enthesitis or dactylitis) |

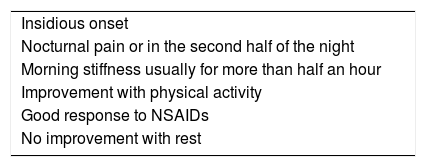

One of the cardinal clinical manifestations is the presence of inflammatory lower back pain, which is frequently difficult to identify and the characteristics of which are summarised in Table 3.3,9,16,21,22

Clinical characteristics of inflammatory joint pain.

| Insidious onset |

| Nocturnal pain or in the second half of the night |

| Morning stiffness usually for more than half an hour |

| Improvement with physical activity |

| Good response to NSAIDs |

| No improvement with rest |

NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

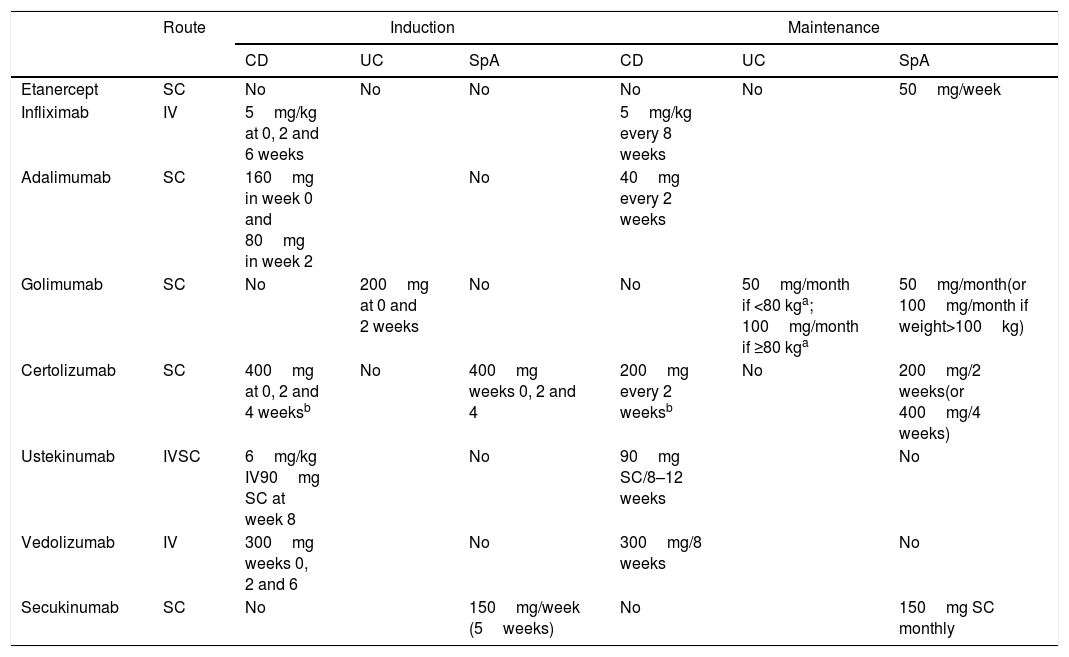

The conventional treatment for SpA basically includes non-pharmacological measures and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), whether classic or specific COX-2 inhibitors (COXIB), although sulfasalazine can also be considered in the peripheral forms. The use of NSAIDs, although common in SpA, is controversial in IBD. It therefore warrants a specific discussion in this document. The different biological alternatives for SpA and IBD are summarised in Table 4.9,23–27

Dose and posology of biological therapies in their different indications.

| Route | Induction | Maintenance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | UC | SpA | CD | UC | SpA | ||

| Etanercept | SC | No | No | No | No | No | 50mg/week |

| Infliximab | IV | 5mg/kg at 0, 2 and 6 weeks | 5mg/kg every 8 weeks | ||||

| Adalimumab | SC | 160mg in week 0 and 80mg in week 2 | No | 40mg every 2 weeks | |||

| Golimumab | SC | No | 200mg at 0 and 2 weeks | No | No | 50mg/month if <80 kga; 100mg/month if ≥80 kga | 50mg/month(or 100mg/month if weight>100kg) |

| Certolizumab | SC | 400mg at 0, 2 and 4 weeksb | No | 400mg weeks 0, 2 and 4 | 200mg every 2 weeksb | No | 200mg/2 weeks(or 400mg/4 weeks) |

| Ustekinumab | IVSC | 6mg/kg IV90mg SC at week 8 | No | 90mg SC/8–12 weeks | No | ||

| Vedolizumab | IV | 300mg weeks 0, 2 and 6 | No | 300mg/8 weeks | No | ||

| Secukinumab | SC | No | 150mg/week (5weeks) | No | 150mg SC monthly | ||

CD, Crohn's disease; IV, intravenous administration; SC, subcutaneous administration; SpA, spondyloarthritis; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Both the traditional NSAIDs and coxibs are indicated as first-line treatment for SpA for the management of pain and morning stiffness.9,28,29

Conventional analgesics such as paracetamol are frequently used as an alternative in patients for whom the use of classic NSAIDs or coxibs is contraindicated, especially from the gastrointestinal point of view; however, there is no specific evidence of their usefulness in SpA and a recent meta-analysis suggests that the use of paracetamol in arthritis is ineffective.9,29–31

The influence of classical NSAIDs or coxibs on the activity or onset of relapses of IBD is controversial and the summary of product characteristics of the majority of NSAIDs include the recommendation of the regulatory authorities not to use them in IBD, which represents a significant determining factor in decision-making in daily clinical practice. Many limitations exist to be able to assess the safety of these treatments in patients with IBD. There is no direct evidence that they cause deterioration of the IBD, since data from controlled studies are very limited. However, NSAIDs are a potential cause of intestinal damage in the small or large intestine, which cannot be prevented with the concomitant administration of proton pump inhibitors and which may also occur in patients who do not present IBD. However, not all NSAIDs carry the same risk of toxicity30; although the gastrointestinal toxicity of coxibs appears to be less than the other NSAIDs, its potential cardiovascular toxicity may limit its use. Finally, it is probable that the predisposition to the toxicity of NSAIDs in IBD is individual, and only the clinical course of each patient allows individualised therapeutic strategies to be established.32–34

Different studies suggest that NSAIDs are associated with a discreet increase in IBD relapse risk. Although the available data are not very conclusive, they indicate that coxibs may be safer than classical NSAIDs in this context.33,35,36 There is little information regarding the possible underlying mechanisms in the induction of exacerbations in IBD with respect to NSAIDs. Among these is the inhibition of COX, which reduces the production of prostaglandins, essential for maintaining the defence mechanisms of the intestinal mucosa.30,33 There does not appear to be a greater risk of exacerbation of IBD in patients treated with celecoxib for 2 weeks37 or etoricoxib for 3 months,38 which suggests that treatment with coxib, at least in the short term, could be safe in IBD, although the limitations of the studies mean that these data should be taken with caution.33,39,40

Thus, considering the activity of the IBD and the risk of intestinal toxicity, it would be prudent to avoid the use of classical NSAIDs and even coxibs, where possible, in cases of active IBD or cases that are difficult to control. Control of the inflammatory process should be achieved with the treatments available, whether these are conventional or biologic immunomodulators, and use alternative analgesics (such as paracetamol and, in some cases, even opiates) whenever possible. In cases where the IBD is well controlled, the cautious use of coxibs for the shortest time possible is acceptable.30,33 Where it is necessary to use a classical NSAID for an intercurrent acute process, it would be convenient to select the one with the best gastrointestinal safety profile (ibuprofen or naproxen).30 In any case, it is recommended that the physician have an open conversation with the patient about the uncertainties regarding the use of NSAIDs in the context of IBD, and that the patient is provided with the most positive information on the risk and benefits of their use.

Management of specific clinical situationsThere are guidelines and recommendations for the management of both IBD and UC as well as for the different forms of SpA.23,24,26,27 However, the association of these entities in the same patient involves taking different aspects of both diseases into consideration when applying these recommendations in a rational manner for each individual patient.6,8,16

Active inflammatory bowel disease and axial spondyloarthritisLower back pain with inflammatory characteristics in a patient with IBD must lead one to suspect the presence of associated axSpA. Given the therapeutic implications of the association, the gastroenterologist must adopt a proactive attitude in the detection of symptoms that permit the suspicion of this association in patients with IBD.12,15,41,42 More than an adequate differential diagnosis, in patients with prior exposure to systemic corticosteroids, vertebral fracture must always be ruled out.23,24

Although mesalazine and sulfasalazine may be effective in certain patients with UC, there are of no use for axSpA.9,23,24 While NSAIDs are useful in the management of axSpA, they do not appear to be the best option in this scenario (see section 4.1). Furthermore, neither systemic corticosteroids or immunomodulators such as thiopurines (azathioprine or mercaptopurine) or methotrexate have proved to be effective in axSpA.16,23,24

Infliximab and adalimumab have proved to be effective in the induction and maintenance of remission in both luminal and perianal CD, while infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab have proved to be effective in UC and also axSpA. Furthermore, biologic therapies in axSpA are indicated in patients who are refractory or intolerant to NSAIDs, which cannot be recommended in general or for long periods in patients with IBD. Consequently, this alternative must be considered jointly by the gastroenterologist and rheumatologist, and be individualised for each patient in whom both entities coexist, as recommended in the first European consensus on the extraintestinal manifestations of IBD.6,8,16 The recommended dosage of infliximab, adalimumab or golimumab in this context are those that have proved to be effective in IBD, since they are greater than those usually used in patients who only suffer from axSpA, and would therefore be effective doses for both diseases (Table 4).

Both etanercept and secukinumab, in spite of being useful in the treatment of axSpA have not proved to be effective in IBD and have even been associated with the onset of new cases of IBD.43–47 Vedolizumab has proved to be effective in IBD, but is mechanism of action, with high intestinal selectivity, and the experience reported in axSpA do not make it a very recommendable option in this clinical scenario.19,48,49 Although ustekinumab has proved to be useful in IBD, its role in axSpA has not been demonstrated: while an initial study suggested that it could be useful at the same dose as for IBD, this has not been confirmed in controlled studies.50,51

In summary, for patients with active IBD and associated axSpA, it is recommended that biologic anti-TNF αtherapy be considered in a joint and individualised manner (infliximab, adalimumab or golimumab, the latter only in the case of UC).

Active inflammatory bowel disease and peripheral spondyloarthritisAlthough peripheral arthritis is a manifestation associated with IBD, other situations exist that may provoke arthralgia and which must be considered in the differential diagnosis, and considering the possibility that the arthralgia are related to one of the treatments received such as corticosteroids, thiopurines or biologic therapies.16 Rheumatoid arthritis or osteonecrosis must also be included in the differential diagnosis.6,8

Peripheral arthritis usually improves with NSAIDs, with the use of COX-2 inhibitors in short cycles apparently being more appropriate in these types of patients, although this cannot be generally recommended in this context (see section 4.1).

It is commonly accepted that peripheral arthritis (fundamentally oligoarthritis with or without enthesitis or dactylitis) is associated with the activity of IBD and it is usually sufficient to control this in order to control the associated pSpA. Accordingly, therapeutic efforts must be aimed at achieving the remission of IBD, whether with aminosalicylates in the case of UC, systemic corticosteroids or biologic drugs, principally anti-TNF-α, according to the clinical situation.6,8,16 The appropriate doses of biologic therapies should be those that correspond to IBD which, being higher, would be useful in both diseases (Table 4).16,27,52,53 In line with the above, and to the extent that vedolizumab is effective in IBD, this can be associated with beneficial effects for pSpA associated with the IBD activity in some patients.54,55 The role of ustekinumab, although clearly established in another type of SpA (psoriatic arthritis), is not specifically defined in IBD-associated pSpA.

If the joint involvement is limiting, specific measures such as rest, physiotherapy or even the local steroid injection are reasonable. Although aminosalicylates do not have a clear indication in CD, data exists that justify treatment with sulfasalazine in cases of CD and pSpA; the replacement of mesalazine with sulfasalazine (2-3g/day) in patients with UC and pSpA may be prudently considered, taking into account the possible toxicity of sulfasalazine at high doses.6,8,27

Methotrexate may be useful as a treatment for CD and there are data that suggest its usefulness in patients with pSpA, consequently it can be considered as an alternative in the case of CD and associated pSpA, although the level of experience and evidence in both cases is limited.16,53 Where combined treatment consisting of a biologic and immunosuppressant drug is considered for IBD, methotrexate would be a reasonable choice instead of azathioprine in patients with associated pSpA, taking into account that when used in combination with an anti-TNF drug, it would appear that methotrexate is effective from 12.5mg/week.53,56

In summary, for patients with active IBD and associated pSpA, the treatment priority should be induction of IBD remission whether with conventional or biologic therapies. In some cases, it may be necessary to combine specific treatments for pSpA.

Active axial or peripheral spondyloarthritis and quiescent inflammatory bowel diseaseA poor correlation exists between the absence of symptoms, the normality of serum biomarkers and the absence of mucosal lesions in IBD.57,58 In other words, the absence of symptoms does not necessarily mean that the IBD is totally controlled.26 Thus, given the presence of symptoms of SpA that oblige a change in the therapeutic approach in a patient who does not present any clear gastrointestinal symptoms, it is recommended that the patient is assessed by Gastroenterology to rule out the presence of IBD activity, even if sub-clinical, in order to establish an overall treatment plan.

The initial approach in this scenario is clinical assessment and conventional tests. It should be noted that SpA is not characterised by an accompanying elevation of acute-phase reactants, thus elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein should lead to suspected sub-clinical IBD activity.6

In cases where there is suspicion or doubts regarding the activity or quiescence of the IBD, it may be necessary to resort to complementary examinations. In general, the most reliable way of ruling out the presence of mucosal lesions in IBD is gastrointestinal endoscopy, but it remains a procedure that is not always the desirable option and the invasive nature of which means that it is not always well accepted by patients. Alternatively, and according to the context, ultrasound, magnetic resonance enterography or the measurement of calprotectin in faeces as marker of inflammatory activity in IBD can be used.59,60

If the presence of the relevant disease activity is found, even on a sub-clinical level, it would be reasonable to consider IBD as active and follow the recommendations proposed above.

If the IBD is found to be effectively in remission, the treatment should be aimed at achieving remission of the SpA, taking into account the nature and therapeutic needs of the associated IBD. Specific measures such as physiotherapy or local steroid injection may be useful.6,8,23,24 NSAIDs should be used with caution and the use of short cycles of coxibs seems more appropriate (see section 4.1.). It may be useful to use sulfasalazine even in patients with CD or instead of mesalazine in patients with UC in the case of pSpA, but not so in the case of axSpA, in a prudent manner and taking into account the possible toxicity of sulfasalazine at high doses.

The use of immunosuppressants in pSpA should involve consideration of the nature and therapeutic needs of the concomitant IBD. Thus, methotrexate could be a reasonable alternative in the case of pSpA associated with CD, although experience and evidence are limited.16,53 The limited experience with leflunomide in IBD in addition to its safety profile (its most common side effect is diarrhoea), make it unattractive for these patients. In patients whose IBD is maintained in remission on treatment with azathioprine, its substitution for methotrexate with the intention of also controlling the symptoms of pSpA should be carefully considered, since the evidence and experience are limited, especially in patients with UC.53

In the event that these measures are not sufficient, biologic therapy with anti-TNFαis indicated, taking into account that its use could be reasonable according to the regimen and dose of infliximab, adalimumab or golimumab recommended in Rheumatology (Table 4), which are different to those recommended for patients with IBD.9,23,24 The most reasonable option would be to select an anti-TNF biological agentα that has been proven to be useful in the IBD of each patient, even if this is inactive. In this respect, golimumab should only be considered when the IBD is UC and etanercept should be avoided.43,44 Given that certolizumab is not approved for IBD in Europe, this is possibly not the most appropriate option. Similarly secukinumab, although effective in SpA, would not be a reasonable option either in this scenario.

Finally, if the patient maintains the IBD in remission thanks to an anti-TNF α therapy, in spite of which the SpA remains active and it is considered that methotrexate could be useful to control the latter, it may be reasonable to associate methotrexate with biological therapy if the patient was on monotherapy or even substitute azathioprine (where combined with an anti-TNFα) for methotrexate, using the dose and route of administration considered adequate by Rheumatology.

If the IBD is controlled with vedolizumab or ustekinumab, it could be reasonable to evaluate the change of therapeutic target, above all in the case of axSpA or if other measures are not useful in the case of pSpA, always carefully assessing all alternatives jointly between Gastroenterology and Rheumatology.19

In summary, a patient with active SpA who does not present clear gastrointestinal symptoms, should be assessed by Gastroenterology to rule out associated IBD activity. Although this may be effectively in remission, it should be taken into account when establishing the treatment for SpA.

Active inflammatory bowel disease and quiescent axial or peripheral spondyloarthritisTreatment in these cases should be aimed at achieving remission of the IBD, following the general approach to treating IBD in each of its different scenarios, but taking into account the nature and therapeutic needs of the associated SpA.

In cases where NSAIDs are used to maintain the remission of SpA, this treatment should be avoided and alternative treatments used (see section 4.1). It is possible that this limitation implies the consideration of anti-TNF α therapy as an alternative, which should be taken into account when deciding how to treat IBD.9,16,23

In the case of UC, it may be advisable to increase the dose of aminosalicylates, which is not always possible when sulfasalazine is the drug in question. With respect to the use of immunomodulators, it would not be necessary to change criterion if the use of azathioprine is intended for the treatment of IBD, a frequent alternative, if the SpA does not require immunosuppressants to maintain it in remission. If the patient who requires immunosuppressants for IBD is already receiving methotrexate for any type of pSpA, it is not appropriate to replace this with azathioprine since this is not useful in SpA.6 Furthermore, it may be possible that the dose received by the patient to maintain SpA in remission is insufficient to induce or maintain CD in remission and the patient may benefit from a dose adjustment or change of route of administration. This is not the case for patients with UC.53 If methotrexate is not useful in the induction or maintenance of the IBD in remission in spite of its effectiveness in the control of SpA, the use of biological therapies would be indicated, whether this be anti-TNFα or not.26,27 Moreover, if the SpA is controlled with leflunomide it is reasonable to propose a therapeutic alternative in patients with IBD activity.8,16

For patients in whom the SpA remission is maintained with anti-TNFα biological therapies, but who present IBD activity, it is possible that the doses that are sufficient for SpA are not so for IBD.9 These patients may benefit from a dose adjustment or even an induction regimen and also from the combination of an immunosuppressant or even a change of biologic. The possibility of determining drug and antibody levels may be of help in making the best decision.61 If the anti-TNF α therapy used to maintain the SpA remission is not appropriate for IBD, a change of biologic may be reasonable (Table 4). Furthermore, if the SpA requires anti-TNF α therapy to remain in remission, it is necessary to avoid, as far as possible, the change of therapeutic target in IBD treatment.

In this respect, it should be noted that although secukinumab is effective in SpA, its efficacy has not been demonstrated in IBD and, given its possible association with the development of denovo cases of IBD it would seem appropriate to change the therapeutic target to another that is common to IBD.46

In summary, in a patient with active IBD and SpA in remission, it is recommended to limit as much as possible the use of NSAIDs, including coxibs, and follow the general treatment guidelines for IBD taking into account the treatments that are necessary to control the SpA.

Conflicts of interestAll authors meet the requirements for authorship and declare the following conflicts of interest:

Yago González Lama. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: AbbVie, MSD, Takeda, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Ferring, Tillotts Pharma, Kern Pharma, Gebro Pharma, Medtronic, Janssen, Pfizer and Amgen.

Javier P. Gisbert. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

María Chaparro. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, AbbVie, Hospira and Dr. Falk Pharma.

María Esteve. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: Tillotts Pharma, AbbVie, MSD, Gebro Pharma and Takeda.

Guillermo Bastida. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: Zambon, Takeda, AbbVie, Jansen, Pfizer, Ferring and Shire.

Ana Gutiérrez. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: AbbVie, MSD, Takeda, Hospira, Kern Pharma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Faes Farma and Ferring.

Eugeni Domènech. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Takeda, Celgene, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Tillotts Pharma, Gebro Pharma and Otsuka Pharmaceutical.

Rocío Ferreiro. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: AbbVie and Tillotts Pharma.

Fernando Gomollón. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: Biogen, Kern, Hospira, Takeda, AbbVie, Shire and MSD.

Beatriz Sicilia. Scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD and AbbVie.

The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest relating to this work.

Please cite this article as: González-Lama Y, Sanz J, Bastida G, Campos J, Ferreiro R, Joven B, et al. Recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) sobre el tratamiento de pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal asociada a espondiloartritis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:273–283.