Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are currently one of the most widely used drugs. The use of NSAIDs is associated with gastrointestinal toxicity, affecting both upper gastrointestinal tract (peptic ulcer disease) and lower gastrointestinal tract (NSAID induced enteropathy).

NSAIDs use has been associated with an increased risk of clinical relapse in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. In this article, we review the upper and lower gastrointestinal toxicity of NSAIDs, with a focus on the risks and specific data of these drugs in IBD patients, giving recommendations for its appropriate use in clinical practice. Although evidence is scarce, short-term use of NSAIDs appears to be safe, and the data available suggest that selective COX-2 inhibitors are the safer option. NSAIDs should be avoided as long-term treatment or with high doses, especially in patients with active inflammation.

Los antiinflamatorios no esteroideos (AINEs) son uno de los grupos de fármacos más frecuentemente utilizados en la actualidad. El uso de AINEs implica riesgo de toxicidad gastrointestinal, pudiendo afectar tanto al tracto superior (úlcera péptica) como al inferior (gastroenteropatía por AINEs).

La toma de AINEs se ha relacionado con un empeoramiento clínico en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII). En este artículo realizamos una revisión acerca de la toxicidad gastrointestinal alta y baja de los AINEs, centrándonos especialmente en los riesgos y datos característicos de estos fármacos en pacientes con EII, estableciendo recomendaciones para su uso en la práctica clínica. Aunque la evidencia es limitada, pautas cortas a dosis bajas de AINEs parecen seguras, y los datos sugieren que los inhibidores selectivos de la COX-2 son la opción más segura. Se debe evitar su uso a largo plazo o a dosis altas, especialmente en pacientes con inflamación activa.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are one of the most frequently used families of drugs today, due to their anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic effect. NSAIDs include multiple drugs with a heterogeneous chemical structure, which have in common their mechanism of action, based on the inhibition of the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme, which catalyses the synthesis of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid. COX has two main isoforms: COX-1, constitutively expressed in most tissues, is involved in maintaining homeostasis, mediating protection of the gastric mucosa, platelet aggregation and regulation of renal microcirculation; COX-2 is an isoenzyme expressed in few tissues, but it is inducible by several factors, especially proinflammatory cytokines. The distinction between the functions mediated by both isoenzymes is not well defined. In this sense, it is believed that COX-1 plays an important role in the initial phases of inflammation, prior to the induction of COX-2.

NSAIDs are usually divided into two subclasses: the classic or non-selective ones and the COX-2 selective inhibitors (coxibs). This classification, useful from a practical point of view, is questionable, since all NSAIDs inhibit both isoforms to some extent. In fact, some classic NSAIDs exhibit selective inhibition of COX-2 similar to that of coxibs. In addition, this group of drugs includes molecules with a heterogeneous chemical structure, which determines that each drug has particular effects based on its physicochemical characteristics, also influenced by individual susceptibility and differences in each tissue.1

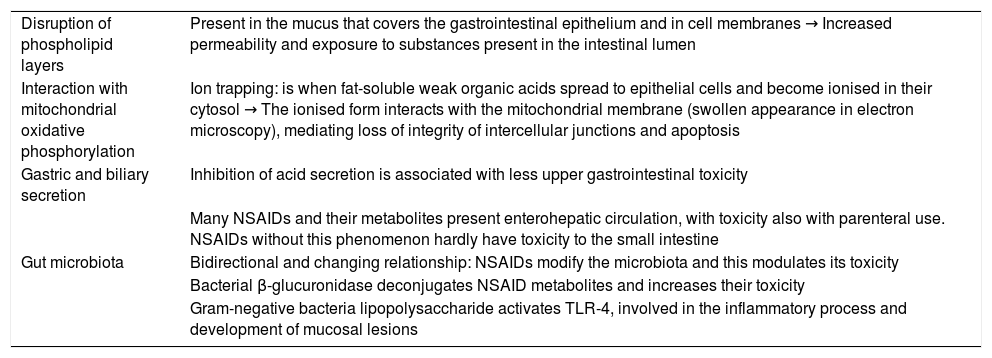

NSAIDs mainly have gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, renal and hepatic adverse effects. In relation to gastrointestinal toxicity, this can appear in any section of the digestive tract and has usually been attributed to the inhibition of COX-1. This inhibition produces a reduction in prostaglandin synthesis in the gastrointestinal tract, inhibits gastric mucus and bicarbonate production, cell proliferation and mucosal blood flow. However, this is not the only factor involved in the gastrointestinal damage associated with NSAIDs. Increasing evidence is available about mechanisms of action independent of COX inhibition.2 These factors are summarised in Table 1.

Mechanisms of gastrointestinal toxicity of NSAIDs independent of COX inhibition.

| Disruption of phospholipid layers | Present in the mucus that covers the gastrointestinal epithelium and in cell membranes → Increased permeability and exposure to substances present in the intestinal lumen |

| Interaction with mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation | Ion trapping: is when fat-soluble weak organic acids spread to epithelial cells and become ionised in their cytosol → The ionised form interacts with the mitochondrial membrane (swollen appearance in electron microscopy), mediating loss of integrity of intercellular junctions and apoptosis |

| Gastric and biliary secretion | Inhibition of acid secretion is associated with less upper gastrointestinal toxicity |

| Many NSAIDs and their metabolites present enterohepatic circulation, with toxicity also with parenteral use. NSAIDs without this phenomenon hardly have toxicity to the small intestine | |

| Gut microbiota | Bidirectional and changing relationship: NSAIDs modify the microbiota and this modulates its toxicity |

| Bacterial β-glucuronidase deconjugates NSAID metabolites and increases their toxicity | |

| Gram-negative bacteria lipopolysaccharide activates TLR-4, involved in the inflammatory process and development of mucosal lesions |

NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; COX: cyclooxygenase; TLR-4: toll-like receptor 4.

Based on Bjarnason et al.2

In summary, the mechanisms by which NSAIDs cause damage to the gastrointestinal mucosa are complex and not completely understood. This is giving rise to new avenues of research with the aim of both finding new therapeutic targets and understanding the effect that NSAIDs have on inflammatory response pathways in the gastrointestinal mucosa, which can influence gastrointestinal diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Clinical dataNSAID-associated lesions in the upper gastrointestinal tractIn chronic users, the risk of peptic ulcer and complications is increased around four times.3 Lesions such as petechiae and ecchymoses can be found in up to 50% of patients, although most are not detected, as they are asymptomatic. The clinical-endoscopic correlation is low, so that a large percentage of patients who take NSAIDs present gastrointestinal symptoms without detectable lesions and, on occasion, a complication is the initial form of ulcer disease associated with NSAIDs.1

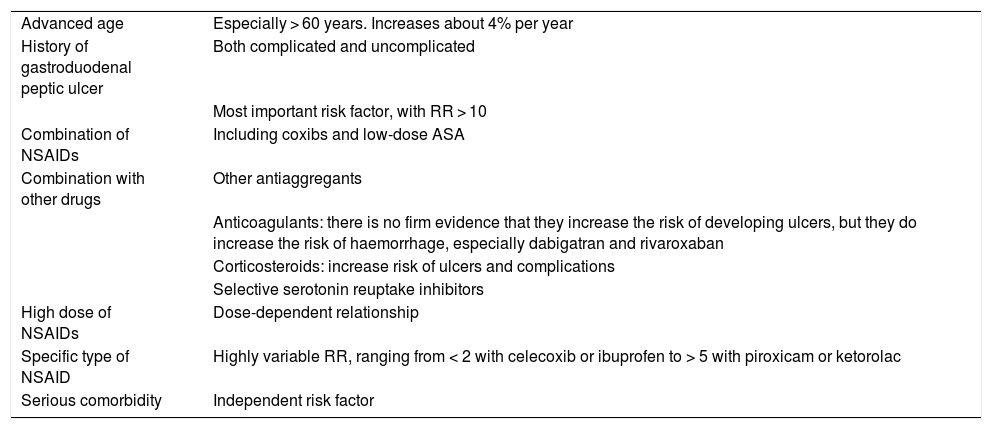

The risk factors for the appearance of lesions in the upper digestive tract are well established4 and are summarised in Table 2.

Risk factors for upper gastrointestinal damage associated with NSAIDs.

| Advanced age | Especially > 60 years. Increases about 4% per year |

| History of gastroduodenal peptic ulcer | Both complicated and uncomplicated |

| Most important risk factor, with RR > 10 | |

| Combination of NSAIDs | Including coxibs and low-dose ASA |

| Combination with other drugs | Other antiaggregants |

| Anticoagulants: there is no firm evidence that they increase the risk of developing ulcers, but they do increase the risk of haemorrhage, especially dabigatran and rivaroxaban | |

| Corticosteroids: increase risk of ulcers and complications | |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |

| High dose of NSAIDs | Dose-dependent relationship |

| Specific type of NSAID | Highly variable RR, ranging from < 2 with celecoxib or ibuprofen to > 5 with piroxicam or ketorolac |

| Serious comorbidity | Independent risk factor |

Mucosal involvement of the small intestine has been detected in up to 70% of chronic users (petechiae, erythematous folds and denuded areas), with the presence of ulcers or erosions in 30−40%. In recent years, there has been a significant increase in admissions for complications in the lower digestive tract compared to those in the upper tract. This is probably due to the existence of well-defined prevention strategies for upper lesions together with a greater availability of diagnostic techniques for the lower digestive tract.5

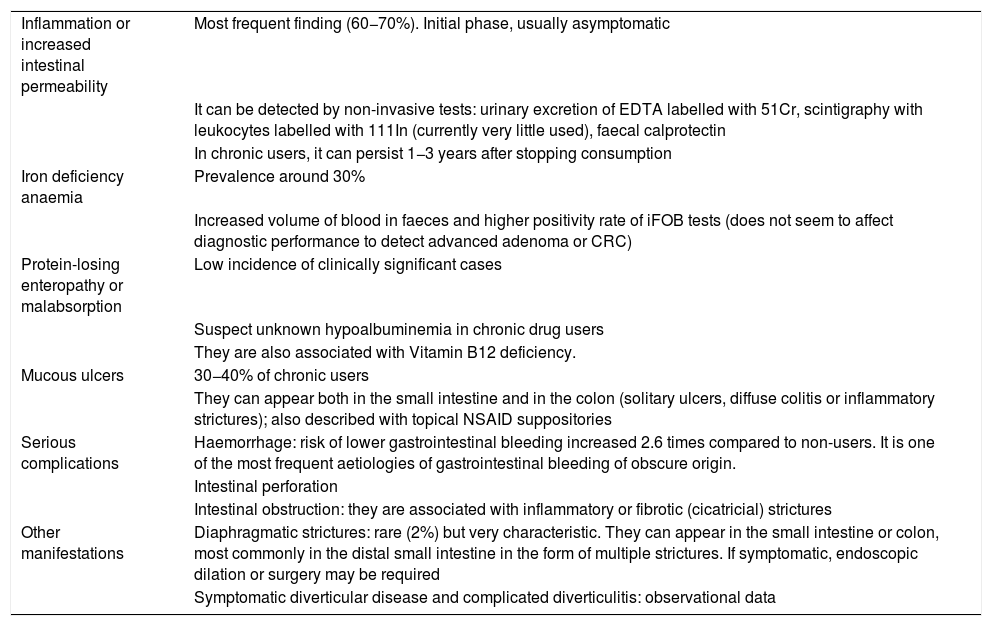

The presentation of small intestine and colon involvement by NSAIDs is nonspecific and its pathogenesis is not as well established as gastroduodenal involvement.5,6 The main clinical manifestations are summarised in Table 3.

Clinical manifestations of damage to the lower digestive tract caused by NSAIDs.

| Inflammation or increased intestinal permeability | Most frequent finding (60−70%). Initial phase, usually asymptomatic |

| It can be detected by non-invasive tests: urinary excretion of EDTA labelled with 51Cr, scintigraphy with leukocytes labelled with 111In (currently very little used), faecal calprotectin | |

| In chronic users, it can persist 1−3 years after stopping consumption | |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | Prevalence around 30% |

| Increased volume of blood in faeces and higher positivity rate of iFOB tests (does not seem to affect diagnostic performance to detect advanced adenoma or CRC) | |

| Protein-losing enteropathy or malabsorption | Low incidence of clinically significant cases |

| Suspect unknown hypoalbuminemia in chronic drug users | |

| They are also associated with Vitamin B12 deficiency. | |

| Mucous ulcers | 30−40% of chronic users |

| They can appear both in the small intestine and in the colon (solitary ulcers, diffuse colitis or inflammatory strictures); also described with topical NSAID suppositories | |

| Serious complications | Haemorrhage: risk of lower gastrointestinal bleeding increased 2.6 times compared to non-users. It is one of the most frequent aetiologies of gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. |

| Intestinal perforation | |

| Intestinal obstruction: they are associated with inflammatory or fibrotic (cicatricial) strictures | |

| Other manifestations | Diaphragmatic strictures: rare (2%) but very characteristic. They can appear in the small intestine or colon, most commonly in the distal small intestine in the form of multiple strictures. If symptomatic, endoscopic dilation or surgery may be required |

| Symptomatic diverticular disease and complicated diverticulitis: observational data |

The risk factors in this location are not superimposable to those of the upper tract, although some (advanced age, concomitant use of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) or antiaggregants) increase the risk in both locations. A study conducted in symptomatic patients diagnosed with NSAID-associated enteropathy identified as risk factors the presence of comorbidity (OR = 2.97), and the use of diclofenac (OR = 7.05) or oxicams (OR = 2.97). An association was also found between genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 and the presence of lesions, specifically CYP2C9*3 with diaphragmatic strictures.7

How to act in practiceNon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, selective COX-2 inhibitors and cardiovascular riskAfter the appearance of coxibs, an increased cardiovascular risk associated with these drugs was detected, which led to the withdrawal of rofecoxib from the market in 2004. However, the classic NSAIDs are also associated with increased cardiovascular risk. In a meta-analysis published in 2014, the risk of cardiovascular events was similar for high-dose diclofenac, ibuprofen and coxibs; naproxen was the NSAID with the lowest cardiovascular risk, and celecoxib was the safest coxib.3

Data from a clinical trial (which included more than 20,000 patients with rheumatological disease who required long-term treatment with NSAIDs and with cardiovascular risk factors) supports this cardiovascular safety of celecoxib. It was concluded that at low doses (200 mg daily) it is not associated with a higher cardiovascular risk than ibuprofen or even naproxen. In this same cohort, the frequency of gastrointestinal complications and iron deficiency anaemia was lower in the celecoxib group than in the other two NSAIDs, although with a low frequency in the three groups (<1%), possibly due to the inclusion of patients with low gastrointestinal risk.8 In another clinical trial with a similar design but including patients who also had a high gastrointestinal risk (previous ulcer bleeding), the rate of rebleeding was 6% with celecoxib combined with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), compared to 12% with naproxen + PPI.9 Thus, low-dose celecoxib could be the safest option in patients with high cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risk.

Treatment of lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tractRegarding the prevention of upper lesions, two main strategies are possible:

- •

Combine NSAIDs with a gastroprotective drug: PPIs are the treatment of choice, as they have been shown to be superior to histamine receptor-2 antagonists in preventing NSAID-associated ulcers and their complications. The efficacy of misoprostol is comparable to that of PPIs, but the high frequency of gastrointestinal adverse effects makes withdrawal of the drug common, which limits its use.10

- •

Use of coxibs: these are associated with a lower risk of peptic ulcer disease, ulcer complications and gastrointestinal symptoms. The combination of coxib + PPI has been associated with a lower risk of upper gastrointestinal complications. The risk is higher in patients treated with isolated coxibs and even higher with classic NSAIDs + PPI.10

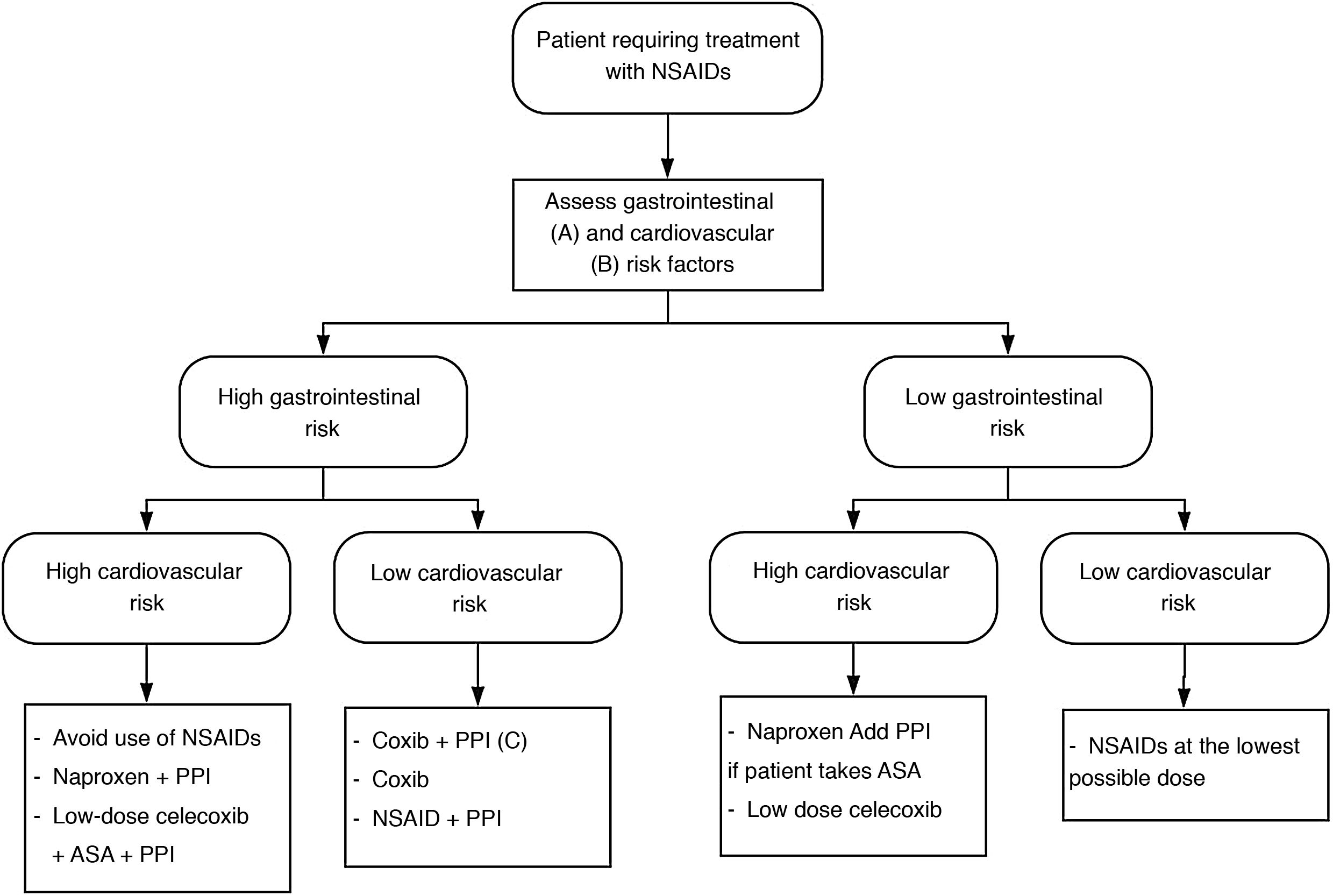

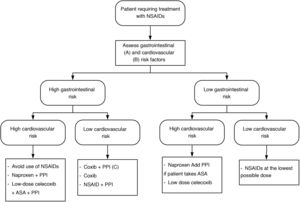

Depending on the cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risk of each patient, the most appropriate strategy to be chosen is summarised in Fig. 1.

NSAID treatment strategies according to cardiovascular and gastrointestinal risk. Modified from Sostres et al.4

ASA: acetylsalicylic acid; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; Coxib: selective COX-2 inhibitors.

A) High gastrointestinal risk: presence of risk factors (age ≥ 60 years, previous ulcer disease, concomitant treatment with antiaggregants/anticoagulants/corticosteroids/several NSAIDs/ASA).

B) High cardiovascular risk: use validated scales (Framingham, SCORE). History of diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular events.

C) Coxib + PPI in patients at very high gastrointestinal risk (history of gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulcer or multiple risk factors).

The treatment of lower digestive tract lesions is less established. The only clearly effective measure is to stop taking NSAIDs.11

Importantly, PPIs do not prevent ulcerative lesions beyond the duodenum. Some studies even indicate that treatment with PPIs could aggravate them, possibly related to changes in the microbiota associated with PPIs.12 The existing evidence about the increase in mucosal damage in the small intestine due to the concomitant intake of NSAIDs/ASA with PPIs is based on experimental studies in animal models and on data from observational studies subject to bias, so new specifically designed studies are necessary to answer this question to be able to give a solid recommendation.

Misoprostol is the drug with the most evidence for the treatment of NSAID-associated small bowel lesions, having shown a higher rate of mucosal healing and recovery from anaemia in clinical trials.11 The high frequency of side effects limits its use, but based on the available evidence, it is currently the first-line drug. Its poor tolerance is especially relevant in patients with IBD, where the appearance of diarrhoea as a side effect can sometimes be indistinguishable from a genuine flare-up of the disease.

The safety of coxibs in the lower gastrointestinal tract is controversial. In some clinical trials, a lower frequency of lesions in the small intestine and colon has been reported, with a risk difference similar to that of the upper digestive tract, while in others no significant differences were found between classic NSAIDs and coxibs.5,11 The discrepancies between studies are due, in part, to not including the same NSAIDs and their doses, which are not always equivalent.

Other treatments have been proposed for which, to date, there is less evidence. Rebamipide, a drug that stimulates the production of prostaglandins and mucus in the gastrointestinal epithelium, has been shown in clinical trials to decrease the frequency of ulcers in the small intestine. The small sample size of these trials must be taken into account and the fact that the data on this drug comes entirely from the Asian population.11 In relation to the role of the microbiota in the pathogenesis of these lesions, treatment with rifaximin or the probiotic Lactobacillus casei have been associated with a decrease in the number of erosions and ulcers.12 Immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory treatments have also been postulated. Observational data in patients with rheumatoid arthritis indicate that treatment with TNF inhibitors could reduce small bowel lesions associated with NSAIDs.13 This data from animal studies or uncontrolled trials has a relative value: it is useful to establish hypotheses or provide information about the pathophysiology of NSAID-mediated intestinal damage, but until it is confirmed in controlled trials, recommendations cannot be established regarding these treatments.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and inflammatory bowel diseasePathophysiology and clinical dataThere are several points to bear in mind when assessing the influence of NSAIDs on IBD. In the first place, and as already mentioned, the heterogeneity of NSAID-associated lesions in the lower digestive tract means that making a differential diagnosis between NSAID-induced enteropathy/colitis and IBD can sometimes be difficult, since endoscopic findings are often indistinguishable. In doubtful cases, histology and evolution after withdrawal of the drug help to make a definitive diagnosis.14

On the other hand, there is controversy about whether NSAIDs may be related to both the onset and the appearance of flare-ups of the disease, in relation to the modulation of the immune response in the intestinal mucosa produced by these drugs.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as a risk factor for inflammatory bowel diseaseSeveral studies link chronic NSAID treatment with an increased risk of IBD onset. A cohort study published in 2012 in which more than 72,000 American women between the ages of 40 and 73 were followed for 18 years, with some 120 incident cases of Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), detected, among other things, that taking NSAIDs for more than 15 days a month was associated with a higher risk of diagnosis of both diseases, with an RR of 1.59 for CD (95% CI: 0.99–2.56) and 1.87 (1.16–2.99) for UC. Lower doses or consumption of ASA were not associated with a higher risk.15

However, another study that followed a cohort of more than 130,000 people (men and women) in Europe for more than 10 years, after 35 incident cases of CD and 84 of UC, reported an increased risk of CD of up to six times (OR 6.14, 95% CI: 1.76–21.3) in patients who were chronic users of ASA, but without finding an association between ASA and UC.16

One limitation of this study that could justify the discrepancy between associations is that the questionnaire they used only collected information about gender, age, smoking habit and treatment with ASA (without collecting details on their indication or previous clinical information), so there could be a bias, in such a way that the consumption of ASA was a marker of cardiovascular or articular damage prior to the diagnosis of CD.

In conclusion, although there does seem to be a certain relationship between NSAID treatment and the risk of IBD onset, the evidence regarding ASA as a risk factor for IBD is not firm.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of flare-up of inflammatory bowel diseaseThe evidence about whether NSAID treatment increases the risk of IBD flare-up is also controversial. A cohort study published in 2016 followed 791 cases of IBD in remission for six months, of which 247 with CD and 89 with UC frequently used NSAIDs. In this study, patients with CD who consumed five or more doses of NSAIDs per month had a higher risk of relapse (RR 1.65; 95% CI: 1.12–2.44), while in patients with UC the risk was not increased. Lower doses did not increase the risk of a UC or CD flare-up. The authors conclude that long-term frequent NSAID intake may be a risk factor for exacerbation of CD.17

Data from a cohort of 629 patients with IBD followed up for five years indicates that short courses of low-dose NSAIDs are well tolerated, while the use of high-dose NSAIDs was associated with worsening on clinical scales in CD patients with colonic involvement, although without a significant increase in risk of flare-up. No differences were found in patients with UC or in patients with CD with isolated ileal involvement.18

The strongest evidence comes from a meta-analysis published in 2018, which included 24 studies (mostly observational and with moderate to high heterogeneity) and concluded that there is no relationship between taking NSAIDs and the risk of flare-up of either CD (RR 1.42; 95% CI: 0.65–3.09) or UC (RR 1.52; 95% CI: 0.87–2.63). It should be noted that when only the studies with low risk of bias (low heterogeneity) were analysed, a subtle but significant increased risk of CD flare-up was detected in patients consuming NSAIDs (RR 1.53; 95% CI: 1.08–2.16), while no significant differences were found for the risk of UC flare-up or for all IBD cases in general. Contrary to what happened with NSAIDs, it did report a significant increased risk of IBD flare-up in patients treated with paracetamol (RR 1.56; 95% CI: 1.22–1.99), although this meta-analysis included only two studies.19

Long et al., in the aforementioned cohort study, also found an association between treatment with paracetamol and the risk of a CD flare-up (RR 1.72; 95% CI: 1.11–2.68).17 However, it should be noted that these relative risks are low and may be subject to bias (paracetamol/NSAID use may be due to poorly controlled inflammation or joint pain prior to the IBD flare-up).

In contrast to these results, in another study that included 209 patients with IBD in the remission phase who were treated for four weeks with different NSAIDs or paracetamol, the relapse rate was 28% in those treated with naproxen, 24% in those treated with indomethacin, 17% in those treated with diclofenac, while no patient treated with ASA or paracetamol suffered a flare-up. In this study, most flare-ups occurred within the first 2–9 days after starting treatment.20

Regarding coxibs, the studies that provide higher quality evidence indicate that treatment with coxibs does not increase the risk of exacerbation of IBD. A double-blind clinical trial published in 2006 included 222 patients with UC in quiescent phase (controlled with 5-ASA or immunosuppressants) who required treatment with NSAIDs. These patients were randomised to receive celecoxib 200 mg or placebo twice daily for 14 days. Treatment with celecoxib did not increase the risk of exacerbation (RR 0.73; 95% CI: 0.17–3.18).21 In another clinical trial, 146 patients with IBD (both CD and UC) with variable inflammatory activity, who required anti-inflammatory treatment due to joint symptoms, were included. They were randomised to receive etoricoxib or placebo for three months and, again, no significant differences were found between the two groups (RR 0.92; 95% CI: 0.37–2.32).22 This data contrasts with those of other studies in which an association was found between the use of coxibs and the risk of flare-ups, although most of these studies are observational and have a smaller sample size. Both the aforementioned systematic review19 and a Cochrane review published in 201423 conclude that there is insufficient evidence regarding the safety of coxibs in patients with IBD, since, although data from clinical trials seems to indicate that they do not increase the risk of flare-ups, the number of events was low and the follow-up time was short.

The mechanisms by which NSAIDs could induce flare-ups or clinical worsening in patients with IBD are similar to those that produce gastrointestinal damage in patients with previously healthy mucosa. In this sense, a study in which NSAIDs with different mechanisms of action were administered to patients with IBD indicates that inhibition of both COX-1 and COX-2 is required to increase the risk of a flare-up (not increased by administering COX-1 or COX-2 specific inhibitors).20 These findings correlate with those of another animal model study, in which knockout mice without COX-1 activity all showed a decrease in prostaglandins in the intestinal mucosa of around 95–97%, but they only showed lesions if COX-2 was also inhibited.

Long-term isolated COX-2 inhibition was also associated with small bowel ulcers, despite normal prostaglandin levels.24 COX-2 is believed to play a relevant role in the inflammation and repair mechanisms of the intestinal mucosa in patients with IBD. In biopsies from patients with IBD, the concentration of COX-2 mRNA is higher than in healthy controls, and increases with increasing activity, while there is no difference in that of COX-1 mRNA.

These findings are similar to those of another study in which material from surgical specimens of patients operated on for IBD was analysed, with significantly higher levels of COX-2 and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) being found compared to patients operated on for diverticular disease.25

Influence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the response to treatment in inflammatory bowel diseaseAnother aspect to consider is whether NSAIDs can influence the response of IBD to specific treatment for this disease. It has been postulated that COX-2 activity in the intestinal epithelium may, in addition to modulating the inflammatory response, influence the response to anti-TNF treatment.

In one study, COX-2 activity was evaluated in colon biopsies and in peripheral blood monocytes from UC patients treated with infliximab at the start of treatment and at week 14, differentiating between responders, non-responders or controls (healthy volunteers). It was observed that in monocytes from non-responders, basal COX-2 activation was higher and was not modified by anti-TNF treatment, but that in responders there was a transient increase in COX-2 activity after anti-TNF treatment. The constant activation of COX-2 in non-responders induces a continuous production of PGE2 that is related to the persistence of inflammation in the mucosa. They conclude that an inability to regulate COX-2-PGE2 activity could be a marker of poor response to anti-TNF drugs and sustained inflammation, so that inducible COX-2 activity with an increase in punctual PGE2 synthesis favours mucosal healing, while sustained activation perpetuates inflammation. Thus, the basal expression of COX-2 in the monocytes of patients with UC could be a marker to determine which patients are more likely to respond to anti-TNF treatment.26

Disruption of the phospholipid layers is one of the mechanisms by which NSAIDs damage the gastrointestinal epithelium.2 In the mucosa of patients diagnosed with UC, it has been observed that phospholipid levels are reduced by up to 70 %. Therefore, it has been postulated that treatment with phospholipids could be a therapeutic alternative in these patients. However, in the clinical trials carried out to date, no significant differences have been shown in the mucosal healing rate compared to placebo, although they have been associated with improvement on clinical scales.27

How these mechanisms (COX-2 activity, phospholipids) can be modulated by taking NSAIDs and, therefore, modify the course of IBD should be evaluated in future studies.

One of the main non-invasive markers for monitoring inflammatory activity in patients with IBD is faecal calprotectin. Taking NSAIDs alone is associated with an increase in the level of this marker, so, in patients with IBD, taking these drugs should always be taken into account when interpreting the results. It has been observed that, after two weeks of withdrawing NSAIDs, the level of faecal calprotectin returns to normal.28

How to act in practiceCurrent consensus documents, based on this evidence, acknowledge that there is no evidence to support that NSAIDs should not be prescribed in patients with IBD if necessary, and that a short regimen is unlikely to be harmful.29 Similarly, the guidelines issued for the management of IBD-associated arthropathy also recommend treatment with short courses of NSAIDs for IBD-associated spondyloarthropathy (along with physiotherapy). They do not recommend long-term use of NSAIDs and leave early treatment with anti-TNF drugs as a second step in those patients who are intolerant or refractory to NSAIDs. In cases of peripheral arthritis, control of intestinal inflammatory activity is usually sufficient, but short courses of NSAIDs can also be used to achieve symptomatic relief.30

It should be taken into account that most of the available data comes from observational studies, or ones with a small sample size, which provides weak evidence that does not allow well-founded conclusions to be drawn. On the other hand, there is significant interindividual and intraindividual variability in the therapeutic and toxic effects of NSAIDs, which makes it even more difficult to obtain quality evidence. This variability appears to be related to genetic factors (polymorphisms in genes encoding cytochrome P450 and COX isoforms) and other factors, such as the bidirectional interaction of NSAIDs with the intestinal microbiota.12

In conclusion, there is currently insufficient evidence to state that NSAIDs (whether classic ones or coxibs) induce an increased risk of IBD flare-up. It seems that there could be a slight increased risk of a flare-up, especially in CD patients who frequently take NSAIDs. Similarly, coxibs seem to be a safer alternative, without there being any highly reliable studies reporting an increased risk of flare-ups. Short regimens at low doses of NSAIDs are safe and should not be avoided in patients with IBD if they are considered necessary, but long-term or high-dose use should be avoided in patients with IBD until more solid evidence appears to support their safety, especially in patients with CD or with inflammatory activity.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Hijos-Mallada G, Sostres C, Gomollón F. AINE, toxicidad gastrointestinal y enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:215–222.