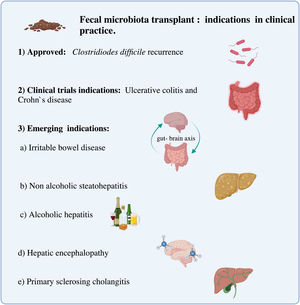

Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) is currently recommended for recurrent Clostridioidesdifficile infection. However, it is interesting to acknowledge the potential therapeutic role in other diseases associated with dysbiosis. This review will focus on the current and potential indications of FMT in gastrointestinal diseases, evaluating the available evidence and also exposing the necessary requirements to carry it out.

El trasplante de microbiota fecal (TMF) está actualmente recomendado en la infección por Clostridioides difficile recurrente; sin embargo, es interesante conocer el potencial rol terapéutico en otras enfermedades asociadas a disbiosis. Esta revisión se enfocará en las indicaciones actuales y potenciales en enfermedades gastrointestinales de TMF, evaluando la evidencia disponible y además exponiendo los requerimientos necesarios para llevarlo a cabo.

The term “dysbiosis” refers to a change in the microbiota, from a healthy pattern to one associated with disease.1 A reduction in the diversity of microorganisms present in the gastrointestinal tract, associated with an imbalance and overgrowth of Proteobacteria is usually characteristic.2 An increasing number of diseases have been associated with dysbiosis, either contributing to the development of the disease or to its severity. Thus, as in Clostridioides difficile (CD) diarrhea, the use of antibiotics causes a change in the microbiota allowing the overgrowth of this bacteria. Although the initial therapy is with enteral antibiotics, between 10 and 30% of patients may experience recurrence, with a risk close to 60% after a third episode.3 It is in this scenario where fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) has shown to have a high rate of effectiveness, tolerance and safety profile, if the pre-established conditions are met.4 Based on these results, it has been proposed that FMT could be used as treatment in other disorders associated with both gastrointestinal and extraintestinal microbiota alterations, highlighting in this last group diseases such as multiple sclerosis, autism spectrum disorders and Parkinson's disease.5

The objective of this narrative review is to describe the indications and future perspectives of FMT in the management of gastrointestinal disorders. A systematized search is carried out in Embase, Web of Science and Pubmed for articles written in English and Spanish from the last 5 years. Also, relevant articles were included manually evaluating the references.

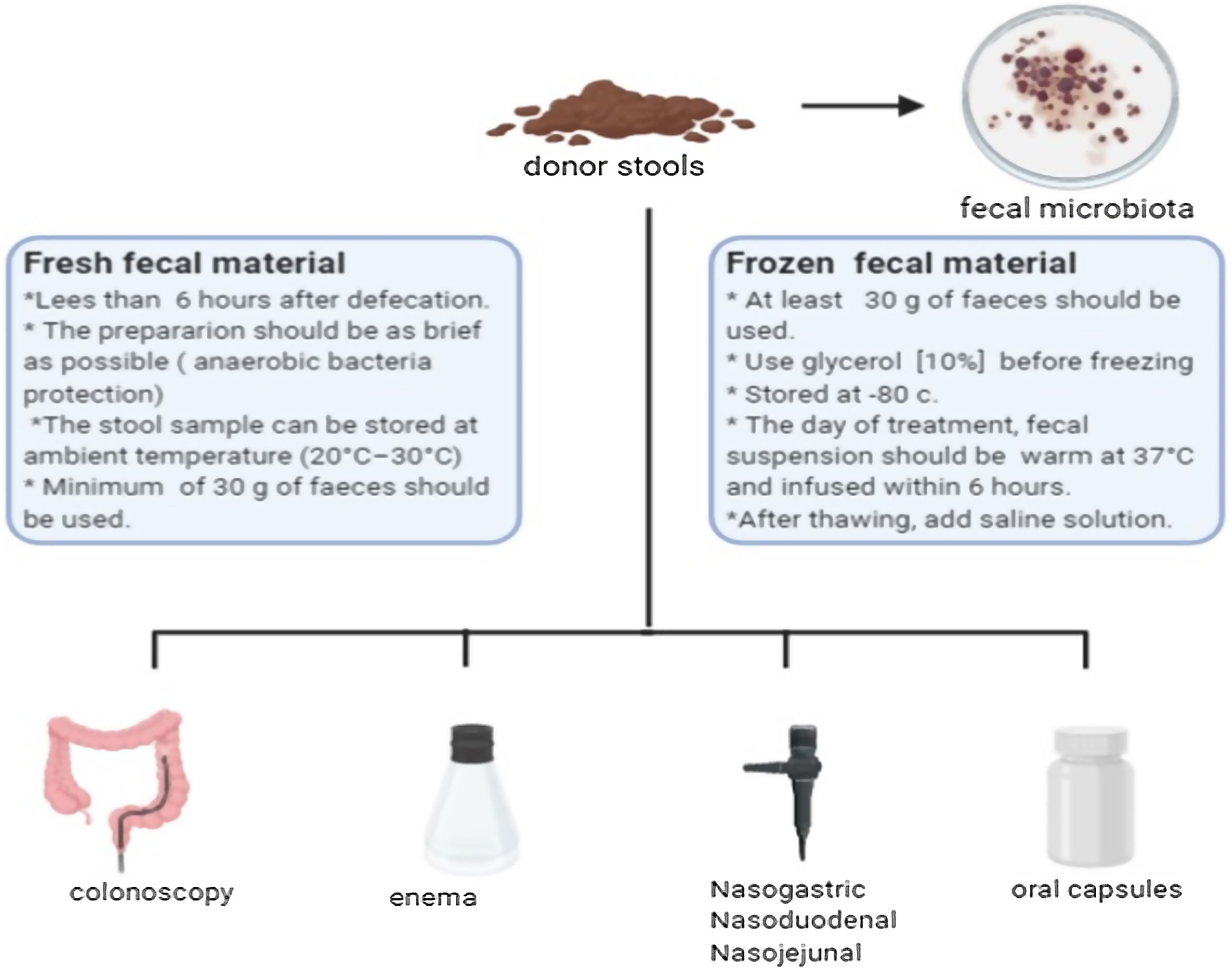

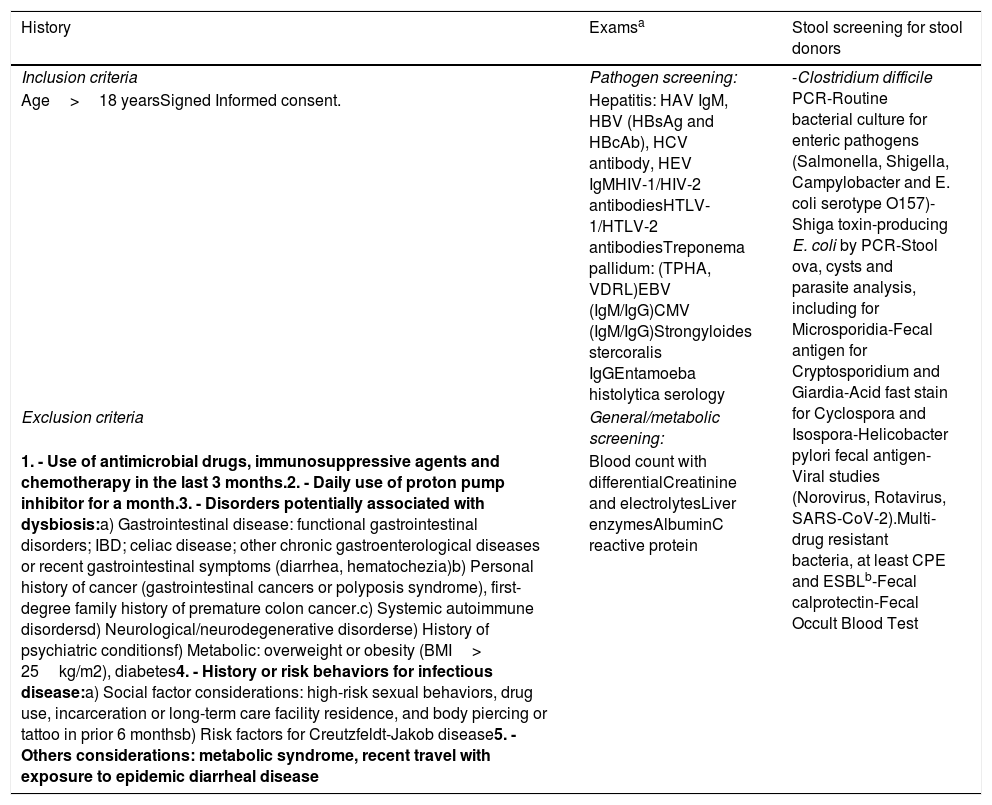

Fecal microbiota transplantBefore mentioning the possible indications for FMT, it is necessary to consider that the selection of the donor represents the most important challenge for the safety of the procedure, having strict exclusion criteria (Table 1).6,7 The ideal donor should be a healthy volunteer, without risk factors for infections or chronic diseases, and who is willing to “donate” frequently if necessary. The concept of super-donors has been proposed in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It refers to that individual, with factors not yet determined from their microbiota, that has a better capacity to treat certain diseases.8 This concept has led to the generation of guidelines for stool banks,9 allowing greater availability, traceability and reduction of associated expenses.10 Fecal microbiota is extracted from the stools of selected donors, allowing the quantity of viable bacteria to be quantified, in order to later use or cryopreserve them.11 The transplant material can be administered by different routes, including oral capsules (Fig. 1).12,13

Summarized donor screening recommendations.5–7

| History | Examsa | Stool screening for stool donors |

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | Pathogen screening: | -Clostridium difficile PCR-Routine bacterial culture for enteric pathogens (Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter and E. coli serotype O157)-Shiga toxin-producing E. coli by PCR-Stool ova, cysts and parasite analysis, including for Microsporidia-Fecal antigen for Cryptosporidium and Giardia-Acid fast stain for Cyclospora and Isospora-Helicobacter pylori fecal antigen-Viral studies (Norovirus, Rotavirus, SARS-CoV-2).Multi-drug resistant bacteria, at least CPE and ESBLb-Fecal calprotectin-Fecal Occult Blood Test |

| Age>18 yearsSigned Informed consent. | Hepatitis: HAV IgM, HBV (HBsAg and HBcAb), HCV antibody, HEV IgMHIV-1/HIV-2 antibodiesHTLV-1/HTLV-2 antibodiesTreponema pallidum: (TPHA, VDRL)EBV (IgM/IgG)CMV (IgM/IgG)Strongyloides stercoralis IgGEntamoeba histolytica serology | |

| Exclusion criteria | General/metabolic screening: | |

| 1. - Use of antimicrobial drugs, immunosuppressive agents and chemotherapy in the last 3 months.2. - Daily use of proton pump inhibitor for a month.3. - Disorders potentially associated with dysbiosis:a) Gastrointestinal disease: functional gastrointestinal disorders; IBD; celiac disease; other chronic gastroenterological diseases or recent gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, hematochezia)b) Personal history of cancer (gastrointestinal cancers or polyposis syndrome), first-degree family history of premature colon cancer.c) Systemic autoimmune disordersd) Neurological/neurodegenerative disorderse) History of psychiatric conditionsf) Metabolic: overweight or obesity (BMI> 25kg/m2), diabetes4. - History or risk behaviors for infectious disease:a) Social factor considerations: high-risk sexual behaviors, drug use, incarceration or long-term care facility residence, and body piercing or tattoo in prior 6 monthsb) Risk factors for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease5. - Others considerations: metabolic syndrome, recent travel with exposure to epidemic diarrheal disease | Blood count with differentialCreatinine and electrolytesLiver enzymesAlbuminC reactive protein |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; BMI: body mass index; HAV: hepatitis A; virus HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HTLV: Human T-cell Lymphotrophic Virus; EBV: Epstein-Barr virus; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; E. Coli: Escherichia coli; PCR: protein chain reaction; CPE: carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae; ESBL: extended spectrum beta-lactamases.

In 2013, van Nood et al. conducted the first randomized controlled study that observed therapeutic advantages of FMT versus conventional therapy in patients with recurrent CD infection. After FMT, patients showed improvement on their microbial diversity, resembling healthy donors, with an increase in Bacteriodetes specie and a decrease in Proteobacteria.14 Since then, important evidence has accumulated on its use in recurrent cases of CD.15 Recent meta-analysis,16 including eight articles with a high level of evidence, showed that FMT was significantly more effective than traditional methods (RR=0.38, 95% CI, 0.16–0.87). These results are similar to what has been reported by previous meta-analysis.17,18 Also, cost-effectiveness studies have shown that FMT by colonoscopy or enema is a cost-effective procedure, having lower direct medical expenses and lower QALYs (quality-adjusted life-years) compared to vancomycin and/or fidaxomicin.19 Based on these results, different scientific societies have suggested that FMT is an effective therapy after a second recurrence due to CD.20,21

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)Ulcerative colitisUlcerative colitis (UC) has become a study model for FMT, given the compromise of the mucosa and the established role of the microbiota in its pathogenesis.22 After the first case in 1989,23 there has been an increase in the number of articles. FMT has been studied in patients with mild to moderate and even severe flare,24 with promising results. However, study designs are varied, making it difficult to compare results. A systematic review showed FMT compared to placebo tended to be more effective in induction of clinical remission (OR: 3.85 [2.21, 6.7] p<0.001) and clinical response (OR, 2.75 [1.33, 5.67] p=0.006) but, non-significant differences were found in terms of corticosteroid-free remission.25 However, it is not yet clear whether one or more FMT administrations are necessary to induce remission or which type of microbiota administered would be the most effective (fresh, frozen, anaerobic).26,27 Although studies with long-term follow-up are lacking, one trial found that in those who achieved remission at 8 weeks, 5 out of 12 remained flare-free. Undoubtedly, more studies are required to confirm these results.28

Regarding maintenance, there are no randomized controlled trials (RCT) showing the use of FMT as a long-term therapy.29

The reported adverse events are a relevant point in this discussion. Although there are no reports of deaths, patients with severe colitis have presented worsening of the condition, need for colectomy in one case, and development of concurrent CD infection.30

Crohn's diseaseSeveral studies have shown efficacy of FMT, around 30% of patients achieve remission and more than 50% have clinical response within a week of treatment,31 showing reduction of symptoms up to 4 weeks after transplantation.32 The best results have been observed with donors with a higher number of Actinobacteria or fewer amount of Proteobacteria, while the transmission of Bacteroidetes has been detrimental.33 Another study showed that a second TMF administered 4 months after the first one maintains the benefits of transplantation.34 Compared to UC, Crohn's disease is a more heterogeneous disease and it may be necessary to evaluate according to the different phenotypes rather than the disease itself.

In recent consensuses, as well as in the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), it has been recommended that FMT in IBD should only be indicated in the context of clinical trials.35

Emerging indications in FMTIrritable bowel syndromeEl-Salhy et al.36 in a recent randomized study show that this therapeutic strategy would be an effective treatment in IBS, without making differences between IBS subtypes. Depending on the amount of stool, 30 or 60 grams was compared against placebo, obtaining a decrease of 50 points or more in the IBS symptom score in 76.9% (p<0.001) and 89.1% (p<0.001) at 12 weeks respectively. Previous studies had shown improvement in symptoms after a single infusion of FMT by colonoscopy in patients with IBS, diarrhea or mixed subtype with p=0.049.37 Tian et al. compared patients with IBS constipation subtype against placebo. Their results showed an improvement in the frequency of bowel movements (more than 3 bowel movements per week) in 53.3% vs 20% in the placebo group after administration of FMT for 6 consecutive days via nasogastric tube. However, adverse events reported in the control group were higher (50 versus 4 cases), most of these being respiratory distress during endoscopy.38 Only one systematic review (SR) with meta-analysis is available, with a very low degree of evidence given by the heterogeneity in the methodology of the studies (I2=79%). This SR showed no significant difference at 12 weeks in IBS symptoms between FMT vs placebo (RR=0.93; 95% CI 0.48–1.79).39

Non-alcoholic steatatohepatitis: NASHThere are dissimilar results on the effect of FMT on risk factors for NASH. In obese patients with no other associated diseases, a randomized study was carried out using FMT in oral capsules in induction and maintenance doses vs placebo. Results showed no improvement in body mass index at 12 weeks, but significant changes in the microbiota were observed (p<0.001).40 In the group of patients with insulin-resistance, another study reported greater sensitivity to insulin at 6 weeks post-transplantation. These was associated with a change in the microbiota, with a higher proportion of Roseburia intestinalis, a butyrate-producing microorganism, even reaching an increase of 2.5 times.41

Alcoholic hepatitisFMT has been proposed as a potential therapy in patients with alcoholic hepatitis (AH). Studies with murine models have shown that manipulating the intestinal microbiota could prevent alcohol-induced liver damage.42 A small report including 8 patients with AH, without criteria to corticosteroid response, were administered a daily dose of FMT for one week, observing an improvement in survival (87.5% vs 33.3%) at one year of follow-up.43

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE)In patients with refractory HE, a randomized trial compared standard therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics followed by a single infusion of FMT using enemas (single donor). Although results showed there was improvement in symptoms at 5-month follow-up, patients maintained therapy with lactulose and/or rifaximin which could be a confounding factor.44 A phase I study, conducted by the same group, evaluated the use of FMT capsules in patients with HE. Results showed the oral route was safe and well tolerated. There was also a variation in the duodenal microbiota with a decrease in Streptococcus and Veillonellaceae and a relative increase in Ruminococcaceae and Bifidobacteriaceae (p=0.01) added to an improvement in cognitive performance (p=0.02).45 However, current studies are small and in order to generate a recommendation it is necessary to include trails with more patients.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)PSC is a chronic and progressive cholestatic liver disease characterized by inflammation and destruction of the intra- and/or extrahepatic bile ducts.46 An association of intestinal microbiota with the pathogenesis of PSC has been described.47 These patients show less diversity and an increase in some bacteria subtypes such as Veillonellas genus, which has been reported up to 4.8 times more frequent in PSC patients than in healthy individuals.48 Its association with IBD is known, which is mainly with UC.49 In a pilot study that included 10 patients with PSC and IBD with elevated alkaline phosphatases (>1.5 times the upper normal limit), single-dose FMT was administered by colonoscopy, and followed-up for 24 weeks. Results showed the procedure was safe and managed to increase the diversity of the microbiota in less than a week (p=0.02), maintaining this condition during follow-up. However, only 3 patients were able to decrease alkaline phosphatase levels. As in many pathologies, randomized controlled trials are required to define the role of FMT as a therapeutic strategy.

ConclusionThe intestinal microbiota is a complex ecosystem of bacterias, viruses, archaea, fungi and other components that are not yet known. There are significant differences in the composition of the microbiota throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Although there is some evidence, it is not enough to determine its role in human metabolism and the development of diseases.

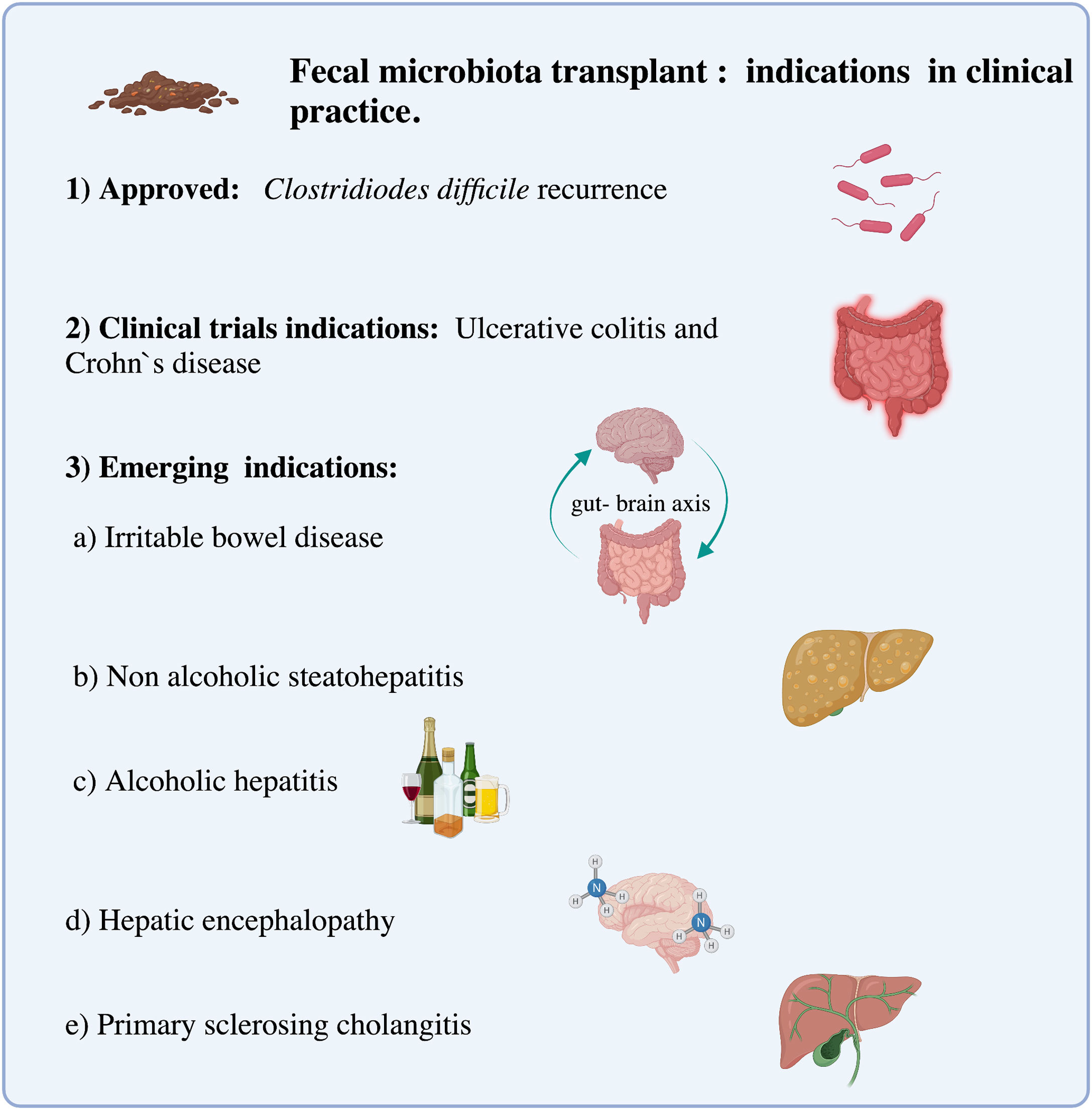

Interest in FMT to treat diseases associated with dysbiosis has increased in recent years3 (Fig. 2). Currently, there is categorical evidence that points to a single gastrointestinal disease, which is recurrent infection by Clostridioides difficile.4

Although FMT is a strategy that is not completely standardized, with different administration routes, types and Schemes,9,10,12 all of them require a safety profile not only in the choice of donors but also in avoiding potential risks. This last point is still important if we consider that among the adverse events, cases of gram-negative bacteremia and deaths have been reported after FMT.50,51 Furthermore, it is important to define whether there are super donors, which would mean that a specific bacteria composition could be more effective in treating a certain disease.8,52

FMT is a promising therapy in several indications related to the human microbiota. However, except for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection, FMT remains an experimental therapy and should only be offered as a therapeutic option in the context of clinical investigation. More randomized controlled trials are required to ensure the potential benefit of FMT compared to standard therapy in other pathologies.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.