Pouchitis treatment is a complex entity that requires a close medical and surgical relationship. The elective treatment for acute pouchitis is antibiotics. After a first episode of pouchitis it is recommended prophylaxis therapy with a probiotic mix, nevertheless it is not clear the use of this formulation for preventing a first episode of pouchitis after surgery. First-line treatment for chronic pouchitis is an antibiotic combination. The next step in treatment should be oral budesonide. Selected cases of severe, chronic refractory pouchitis may benefit from biologic agents, and anti-TNFα should be recommended as the first option, leaving the new biologicals for multi-refractory patients. Permanent ileostomy may be an option in severe refractory cases to medical treatment.

El tratamiento de la reservoritis es un escenario complejo que requiere una estrecha colaboración médico-quirúrgica. El tratamiento de elección de la reservoritis aguda es el ciprofloxacino o el metronidazol. Ante un primer episodio de reservoritis se recomienda la profilaxis de recidiva con una mezcla de probióticos; sin embargo, no está tan clara su utilidad como profilaxis primaria para prevenir un primer episodio de reservoritis tras la cirugía. El tratamiento de la reservoritis crónica refractaria debe iniciarse con una combinación de antibióticos, y si esta fracasa el siguiente escalón terapéutico es la budesonida oral. Algunas formas refractarias necesitarán terapias biológicas, siendo los anti-TNF α la primera opción, reservándose otros biológicos para pacientes refractarios. La ileostomía definitiva puede ser una opción final en los pacientes más graves.

Treatment of pouchitis, particularly chronic pouchitis, is one of the most complex scenarios of inflammatory bowel disease. This is primarily due to the lack of controlled studies, given the small number and heterogeneity of patients with this entity. Moreover, some patients have already received treatments prior to surgery, which may condition the choice of treatment if they develop chronic pouchitis. Therefore, due to this complexity and its high frequency, it is logical that, in addition to treatment, possible prevention strategies for this condition have been considered. This document includes the recommendations on the treatment and prevention of this complication as a continuation of the previous document on its epidemiology, diagnosis and prognosis.1

Can a first episode of pouchitis be prevented?Given the high risk of the appearance of pouchitis in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) who have undergone an ileo-anal pouch operation (40–50% risk 10 years after surgery2,3), preventive attitudes to avoid the appearance of this complication as far as possible must be proposed.4 Several studies have assessed the efficacy of different treatments in this clinical setting.

The only study of high methodological quality carried out is the one led by Gionchetti and published in 2003.5 In this trial, patients in whom a pouch had been made were randomised to receive treatment with a mixture of probiotic strains, then known as De Simone Formulation 3g/day or placebo, after one week had elapsed since the closure of the ileostomy. A total of 20 patients received treatment with the probiotic formula and 20 with placebo. There was a statistically significant difference in the occurrence of pouchitis after 12 months between the group that received treatment with the probiotic mixture (2/20, 10%) and the group that received treatment with placebo (8/20, 40%; relative risk [RR] 1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–2.1).

At this point it is important to clarify the possible confusion currently existing due to there being more than one product on the market, by appealing to the original studies for this indication. All the pouchitis studies were performed with the ‘old’ De Simone Formulation, which is a mixture of probiotic strains containing a high concentration of bacteria (300,000million/g) from a set of 8 different bacterial species: 4 Lactobacillus strains (L. casei, L. plantarum, L. acidophilus and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus), 3 from Bifidobacterium (B. longum, B. breve and B. infantis) and one from Streptococcus thermophilus. The mixture is off-patent, so it can be freely manufactured and distributed. There is a dispute regarding the quality of the final product produced by the different manufacturers,6 although there is no independent and solid evidence that demonstrates differences in terms of their clinical efficacy. This treatment has the disadvantage of not being financed in our public health system and its long-term use may pose a significant economic burden to patients.

It should be noted that another study (open and randomised) also carried out with the same product did not find differences in the rate of appearance of pouchitis after 12 months compared to a group of patients who did not receive treatment.7 There were no cases of pouchitis in the group treated with the probiotic mixture (0/16, 0%) compared to only one case in the untreated group (1/12, 8%; RR 1.10; 95%CI 0.89-1.36).

In another randomised, double-blind study, published only as an abstract,8 the efficacy of probiotics (in this case with Bifidobacterium longum BB-536 versus placebo) was studied in 12 patients, and the Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI) was assessed as the primary endpoint after 6 months of treatment. There was no difference in the proportion of patients who had an episode of acute pouchitis during the 6-month follow-up (1/7, 14% vs. 2/5, 40% in the treatment group and in the placebo group, respectively; RR 1.43; 95% CI 0.66–3.11).

In a retrospective analysis of a single-centre historical series, the effect of the administration of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GC (a bacterial strain used as a probiotic in various digestive diseases) on clinical evolution after an ileo-anal pouch operation was studied in comparison with a historical cohort in patients with UC.9 The cumulative risk of developing pouchitis in patients who received probiotic treatment was 7% at 3 years compared to 29% in those who had not received it (p=0.011).

A Japanese study, randomised but with a limited number of patients (n=17), compared Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI and placebo.10 After a 24-month follow-up, 11% (1/9) of the patients treated with C. butyricum MIYAIRI and 50% (4/8) of the participants treated with placebo developed acute pouchitis (RR 0.22; 95% CI 0.03–1.6).

With the rest of the drugs evaluated, the efficacy of allopurinol11 or tinidazole (the latter evaluated in a study published only in abstract form)12 used to prevent a first episode of pouchitis in operated UC patients has not been demonstrated. A retrospective study of low methodological quality has recently been published in which the use of sulfasalazine (at a dose of 2g/day) seems to offer protection against the development of pouchitis.13 However, these data should be approached with caution until they have been validated by randomised clinical trials that support them.

We recommend that the only treatment that could be effective in preventing pouchitis is the probiotic mixture used in the original studies. However, we must be cautious regarding the robustness of the data that support this treatment, since the number of patients included in the study with the highest methodological quality is very low and the number of pouchitis cases described in that trial is also small. Furthermore, no subsequent quality trials have replicated these findings. Therefore, we cannot recommend its general use in all operated patients for the prevention of pouchitis.

How do we treat acute pouchitis?Antibiotics are the most widely used first-line treatment, being effective in up to 78% of patients.14 In patients with an ileo-anal pouch in whom a first outbreak of pouchitis is suspected, after superinfection is ruled out by a stool culture, an empirical regimen of antibiotics with ciprofloxacin or metronidazole may be indicated. Moreover, while not mandatory, it is definitely advisable to perform an endoscopy (if available) without delay to obtain a biopsy, since most patients will present a response quickly.15

The first clinical trial was conducted in 13 patients and was a double-blind study with a crossover design in which the efficacy of 400mg of metronidazole 3 times a day was compared to placebo for 2 weeks.16 Metronidazole was more effective than the placebo in reducing the number of bowel movements (73 vs. 9%; p<0.05). However, up to 55% of the patients had side effects, dysgeusia and nausea being the most frequent ones.

In a randomised clinical trial with 16 patients, ciprofloxacin showed greater efficacy (remission in 7/7, 100%) compared to metronidazole (in 3/9, 33%) (p<0.05) after 2 weeks of treatment, with a better safety profile, whereby ciprofloxacin may probably be considered the treatment of choice.17

Another antibiotic proposed for the treatment of acute pouchitis is rifaximin. In a placebo-controlled trial conducted in 18 patients who were given 400mg of rifaximin/8h vs. placebo for four weeks, no statistically significant differences were observed.18

Regarding other therapeutic alternatives, high doses of the same probiotic mixture mentioned above are known to be effective in mild acute pouchitis, although the data are not very solid and come from open series not compared with placebo.19

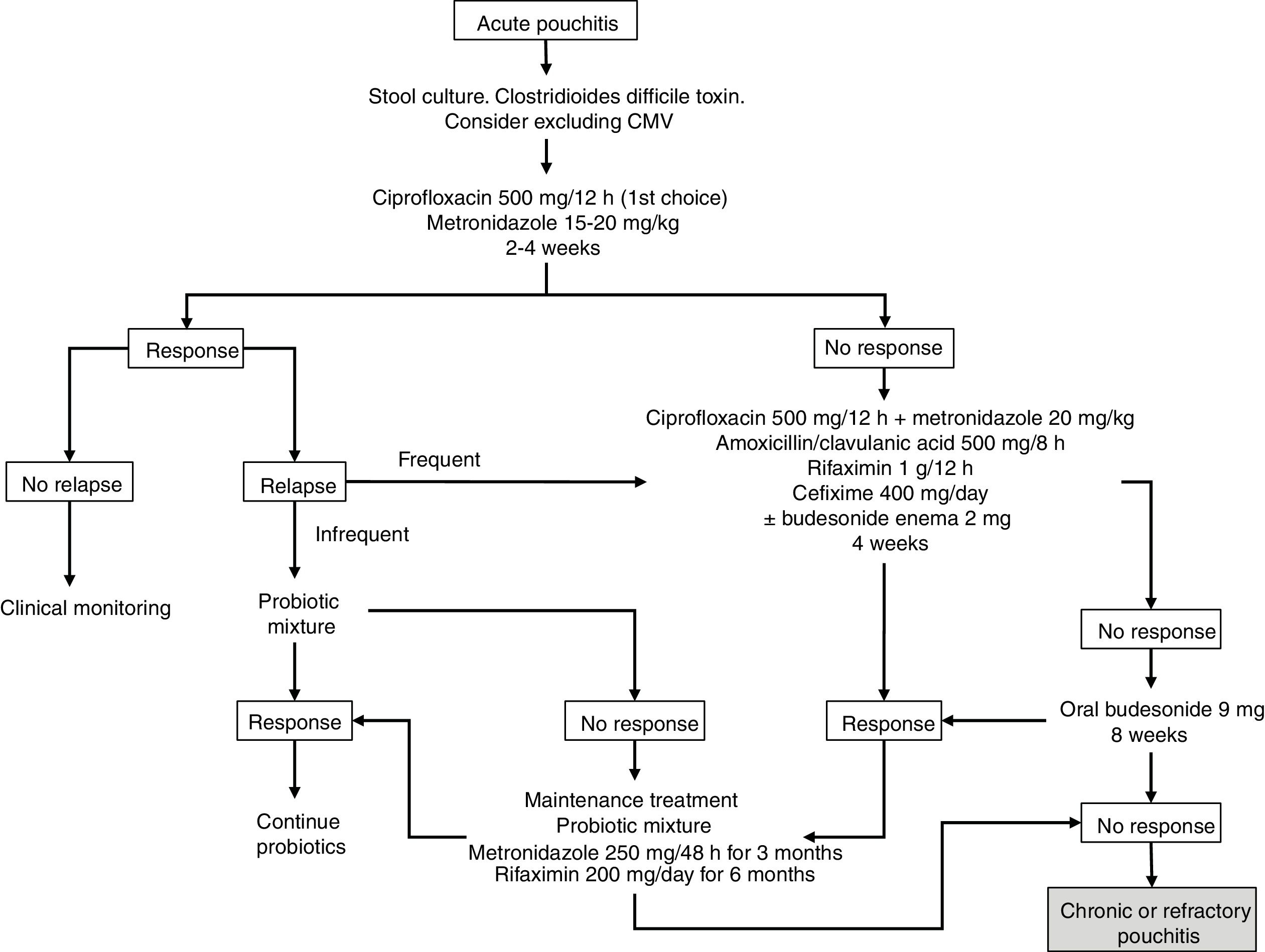

Budesonide has been evaluated, both as enema and oral preparations, in the treatment of acute pouchitis. In a prospective study of 26 patients, budesonide enemas (2mg/100ml at night) were compared to metronidazole (500mg twice a day) for 6 weeks. It was concluded that they were similar in clinical, endoscopic and histological efficacy, with no differences between both groups.20 There are also open series that have demonstrated the efficacy of aminosalicylates administered both orally and topically in acute pouchitis, so these drugs could be taken into account in cases that do not tolerate antibiotics.21 The suggested algorithm for the treatment of acute pouchitis is summarised in Fig. 1.

The use of antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin or metronidazole for 2–4 weeks is recommended as treatment for acute pouchitis, preferably ciprofloxacin due to its better safety profile and probable greater efficacy, with other options such as probiotics, budesonide or mesalazine being reserved for patients with intolerance to antibiotics.

After a first episode of pouchitis, can we prevent new episodes?After an initial episode of pouchitis, patients can develop new episodes, although this does not happen in all cases.1 Patients with at least three annual episodes of pouchitis, despite receiving antibiotic treatment, are considered antibiotic-dependent. In these cases, it is reasonable to propose some type of prophylactic treatment given the significant clinical deterioration and in the quality of life that these episodes can produce in the lives of patients.22

We have data on the efficacy of the probiotic mixture in this clinical context: both the study by Gionchetti et al.23 (single dose of 6g/d) and in that of Mimura et al.24 (dose of 3g twice a day) showed that treatment with this probiotic formulation significantly reduced the risk of reappearance of pouchitis in this type of patient. A joint analysis of both studies (which included a total of 76 patients) showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients who maintained remission after 9–12 months.25 Of the patients in the group treated with the probiotic mixture, 85% (34/40) did not develop episodes of pouchitis compared with 3% (1/36) of those treated with placebo; (RR 20.24; 95% CI 4.28–95.81). This treatment was well tolerated, with hardly any adverse effects in both studies in the arm receiving treatment with the probiotic mixture. In any case, these results should be taken with caution, given that the GRADE analysis of both studies classifies them as low-quality due to their small sample size.

The efficacy of other probiotics has been studied for this type of patient, with less favourable results found.22 The use of L. rhamnosus GC in a double-blind clinical trial which included 20 patients found no differences in clinical or endoscopic variables, despite demonstrating a change in the composition of the bacterial flora of the pouch.26

We also have the results of a study that evaluated the efficacy of oral rifaximin treatment for this type of patient.27 In this open-label study, patients received treatment with rifaximin (at a mean dose of 200mg/day) after 2 weeks of conventional antibiotic treatment. 65% of the patients (33/51) maintained remission after three months and 58% maintained it after 12 months of treatment.

The best current alternative for maintaining remission in patients with previous episodes of pouchitis is the probiotic mixture of the original studies. This is despite the low degree of evidence that supports this due to the small sample size of the studies carried out. This treatment has the disadvantage of not being financed in our public health system and its long-term use may pose a significant economic burden to patients.

What treatments will we use in chronic pouchitis refractory to an antibiotic?Despite antibiotic treatment in acute pouchitis, up to 10-20% will develop an antibiotic-dependent or refractory form of chronic pouchitis. These patients will benefit from new courses of antibiotic or combination therapy.

In a systematic review, the odds ratio for inducing response in chronic pouchitis with metronidazole vs. placebo was 12 (95% CI 2.3–65).28 Combination therapy has been shown to be effective with different types of antibiotics. One study included 16 patients who were given ciprofloxacin 1g/day and tinidazole 15mg/kg/day for 4 weeks and compared with a cohort of 10 patients receiving oral or topical mesalazine.29 The remission rate of the group that received antibiotics was 88% compared to 50% for those receiving mesalazine, and a statistically significant improvement was observed in both PDAI score and quality of life. In another study, 18 patients without a response to metronidazole, ciprofloxacin or amoxicillin/clavulanate for 4 weeks were included and treated with rifaximin 2g/day together with ciprofloxacin 1g/day for 2 weeks.30 Approximately 90% obtained a response and 33% (6/18) achieved clinical remission. No side effects were detected in this study. In another prospective study, 44 patients received 1g of metronidazole together with 1g of ciprofloxacin daily for 4 weeks, 36 (82%) of whom obtained clinical remission.31

Another recent study evaluated the long-term use of antibiotics. It included 39 patients who received antibiotics for at least one year (ciprofloxacin or metronidazole alone or in combination, and rifaximin and cephalosporins as alternatives). Remission was observed in 21% of the patients, albeit with 28% of side effects, especially metronidazole-induced neurological toxicity.32

In patients with antibiotic-dependent chronic pouchitis, the combination of two antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin together with metronidazole or rifaximin for at least 4 weeks is recommended, although it should be taken into account that the risk of adverse effects is high. It is essential that patients with pouchitis being treated with metronidazole be warned of the risk of neurological toxicity, and that self-medication be avoided without strict medical supervision.

Treatment of refractory chronic pouchitisCan we use corticosteroids?Oral corticosteroids with topical action have demonstrated efficacy in refractory chronic pouchitis. In one study, oral budesonide was administered to 20 patients in whom antibiotic treatment for 4 weeks with metronidazole or ciprofloxacin had failed to resolve pouch inflammation.33 The dose used in this study was 9mg/day for 8 weeks, with the dose subsequently reduced by 3mg/month until suspension. 75% of the patients presented remission, defined according to a total PDAI score of ≤4. In this study, the authors found that the number of bowel movements per day decreased significantly in patients (from 10 bowel movements to 6; p<0.01). The impact of treatment on quality of life was evaluated and a significant improvement was observed in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) versus the patients’ baseline score (180 vs. 105; p<0.001). In our setting, the Galdakao group published an open series of 5 patients with refractory pouchitis, 4 of whom (80%) achieved remission measured using the PDAI after 8 weeks of treatment with 9mg of budesonide.34 There is another open study carried out in a group of 10 patients refractory to antibiotics who were treated for 8 weeks with beclomethasone dipropionate, with 80% of the patients reaching remission (PDAI≤4).35

Treatment with topical oral steroids should be attempted in patients with pouchitis in whom antibiotics have failed.

Is the use of immunosuppressive drugs recommended in refractory chronic pouchitis?There are no data available to support the use of thiopurine immunomodulators in monotherapy to achieve remission in refractory chronic pouchitis. The greatest benefit of these drugs in this context is probably obtained from their combination with anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNFα) biologicals to increase their efficacy and response rate. However, it should be noted that no specific studies have been published in chronic pouchitis with a drug so widespread in our setting. Furthermore, in some of the series of patients treated with anti-TNFα, such as that of the Belgian group36 and that of GETECCU,37 more than 50% of the patients had received azathioprine for their pouchitis prior to the use of the anti-TNFα.

Based on the hypothesis that ulcerative proctitis and pouchitis may share certain pathophysiological mechanisms, cyclosporine A, in its 250-mg once-daily enema presentation, could represent a useful treatment in some cases of refractory pouchitis, although data to support its beneficial results are scant.38

The use of immunosuppressive drugs is not recommended in refractory chronic pouchitis.

Should we use biological therapies in refractory chronic pouchitis?The first efficacy data with infliximab (IFX) are from patients who developed findings consistent with Crohn's disease (CD) after a colectomy and reconstruction with a J-pouch after an initial diagnosis of UC.39 The first results on the use of biologicals in patients with pouchitis in UC are from two Italian groups that evaluated the efficacy of IFX in two independent series, with very high remission rates.40,41 In 2010, the results of a Belgian multicentre study were published in which 28 patients with refractory pouchitis were treated with IFX following a classic schedule of induction and subsequent maintenance every 8 weeks. At week 10, 88% had a clinical response, partial in 56% and complete in 32%. Meanwhile, the PDAI decreased from 9 to 4.5 points (p<0.001). After a mean follow-up of 20 months, 56% of the patients presented sustained clinical response, while 5 (17%) patients had to undergo a permanent ileostomy.36 The series published with the largest number of patients (n=33) is that of GETECCU, with 21% of the patients achieving complete clinical response and 63% partial clinical response at week 8.37 At weeks 26 and 52, 33% and 27%, respectively, had achieved complete clinical response and 33% and 18% had achieved partial clinical response. Treatment was interrupted in 13 patients; in 4 of them due to lack of efficacy, in 4 due to loss of response and in 5 (15%) due to adverse effects.

As with IFX, the initial data with adalimumab (ADA) come from pouchitis in CD patients with a colectomy. The main study is by the Cleveland group, which evaluated the efficacy of ADA in 17 patients who developed findings consistent with CD having previously been diagnosed with UC and undergoing a colectomy with ileo-anal J-pouch. The authors observed that after 8 weeks of follow-up, 8 patients (47%) presented a complete clinical response and 4 of them (24%) partial response.42 Among the few available studies that evaluate the efficacy of ADA in pouchitis after a colectomy in UC, there is one by GETECCU that retrospectively analysed the efficacy of ADA in 8 patients with refractory chronic pouchitis, all of them previously treated with IFX.43 The short-term results (week 8) were evaluated, with 13% of the patients reaching remission and 38% with clinical response. Regarding long-term efficacy (week 52), 50% of the patients avoided a permanent ileostomy, although only 25% achieved remission. However, a recently published study comparing ADA and placebo in 13 patients refractory to antibiotics showed no significant differences between the two groups.44

A recent systematic review, which included not only fully published articles (although not that of Kjaer et al.44) but also communications to conferences, concluded that both anti-TNFα drugs are effective in the short and long term in the treatment of chronic pouchitis, although the authors emphasise that the outcomes are better in patients whose final diagnosis is CD.45

With regard to other biological therapies such as vedolizumab, several series have recently been published. The most valuable one is a German open-label multicentre study that evaluated the efficacy of the drug in 20 patients with chronic refractory pouchitis (most of the patients were refractory to anti-TNFα) and observed a PDAI decrease from 10 to 3 points at week 14.46 In another study conducted at the Cleveland Clinic, 19 patients with refractory chronic pouchitis were treated with vedolizumab (more than 50% refractory to anti-TNFα).47 74% of them experienced both clinical (modified PDAI) and endoscopic improvement. This year, the first data on the use of ustekinumab were published, demonstrating clinical and endoscopic improvement in 24 patients with refractory chronic pouchitis, meaning that this drug could also be an effective alternative in multi-refractory cases.48

Treatment with biological therapies should be considered in patients with pouchitis in whom antibiotics and budesonide have failed. First, with anti-TNF, and if there is no response, previous failure or intolerance, vedolizumab or ustekinumab are recommended.

Other treatmentsBacterial overgrowth in the J-pouch probably plays a role in its inflammation. Therefore, given the toxic effect of bismuth on bacterial enzyme systems, it has been postulated that it could have some benefit (administered in the form of enemas or orally) in the treatment of refractory chronic pouchitis. In a 3-week randomised clinical trial in which 20 patients received 270mg bismuth carbomer enemas and 20 patients received placebo, no patient achieved remission, although 9 patients in each group (45%) achieved clinical response with a 3-points reduction with regard to their baseline PDAI.49 The authors of this study attributed the absence of differences in both treatment groups to the low concentration of bismuth in the enemas, the short treatment duration or the therapeutic properties of the resin applied as a placebo.

Alicaforsen is a molecule that inhibits the intracellular adhesion molecule ICAM-1 (CD54). It has been postulated that in patients with active pouchitis the expression of ICAM-1 is increased,50 so an open-label study was carried out in which 12 patients with refractory chronic pouchitis were treated with a daily enema of 240mg of alicaforsen applied at night for 6 weeks.51 At week 6, all patients had a significant PDAI reduction with regard to the baseline (11.4 vs. 6.8; p=0.001). Data from another uncontrolled series of 13 patients who received the same treatment regimen show that a high proportion present clinical improvement (85%), although recurrence is frequent.52 Given the very limited evidence, studies that are capable of providing more robust data and with sufficient statistical potency are needed to validate the use of alicaforsen on a regular basis.

Regarding apheresis techniques in chronic pouchitis, only isolated clinical cases report the efficacy of these techniques in these patients.53

Despite the fact that faecal transplantation, given the pathogenesis of pouchitis, could be considered a reasonable treatment alternative, the current evidence regarding its use is still very limited. The available data are based on isolated case series with a good initial response but without a medium- to long-term follow-up.54,55

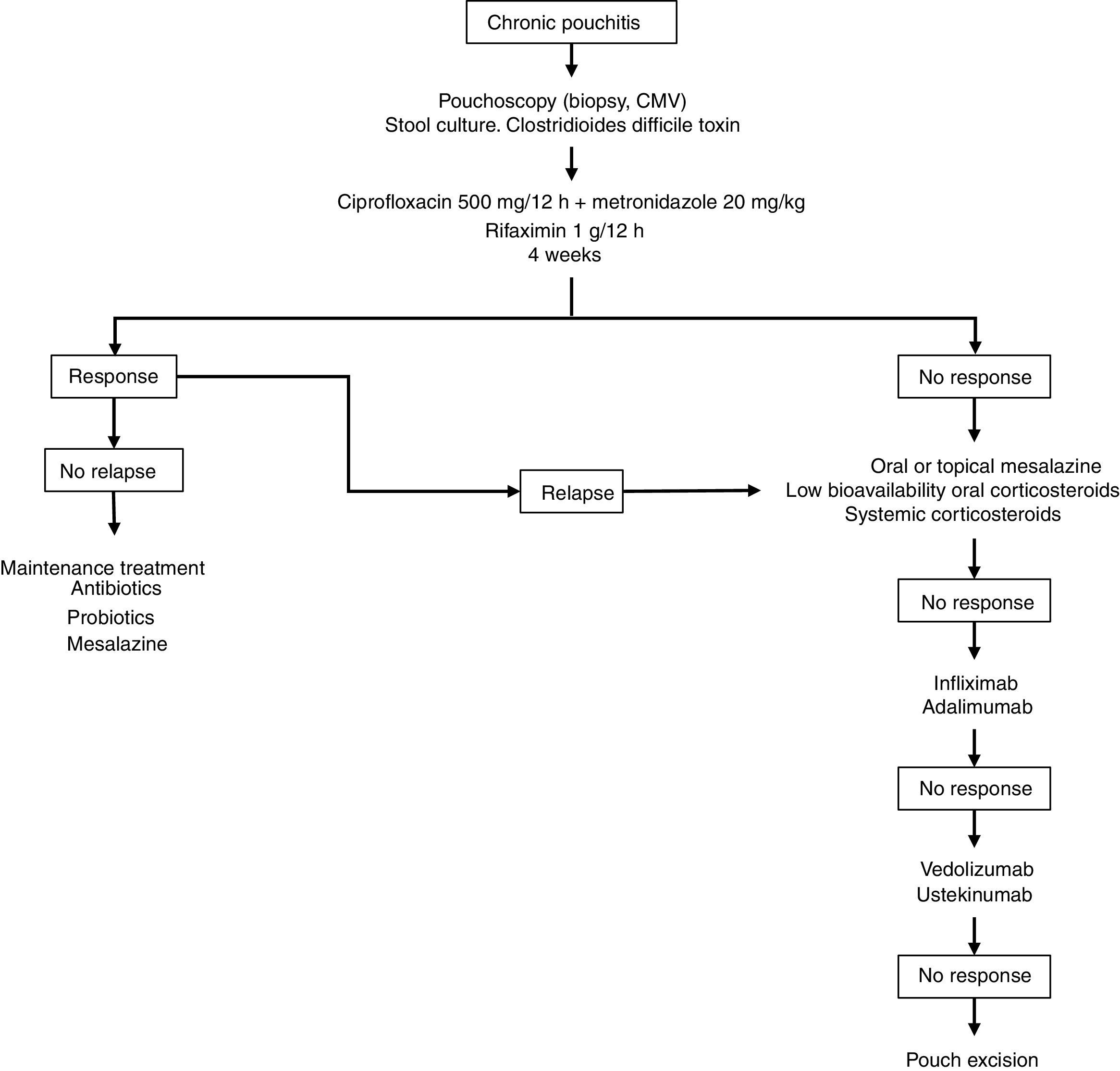

Fig. 2 shows a possible treatment algorithm for chronic pouchitis.

Surgical treatment: definitive ileostomyPouch rescue surgery is an option when medical treatment fails.56 However, surgery in the treatment of pouchitis does not include making a new pouch or part of the existing one, but rather its defunctionalisation through a diversion ileostomy or resection with a pouchectomy with a definitive ileostomy.

The incidence of pouch loss due to chronic pouchitis refractory to medical treatment is difficult to estimate due to the evolution of treatments and the low volume of publications in this regard, although it accounts for nearly 25% of the indications for resection of the pouch.57 In fact, in the series with the most experience worldwide, such as that of the Cleveland Clinic, with nearly 1000 pouches performed, 10% of patients require a definitive ileostomy. These figures are higher when the patients in this series who developed refractory chronic pouchitis are analysed, since the definitive ileostomy rate in them was 24%.58

Temporary defunctionalisation is performed in high-risk patients with the aim of reducing complications derived from resection. However, patients who undergo this bypass should be warned of the persistent leak from the retained pouch and of the lingering symptoms in some of them. There are two published studies comparing short-term and long-term results of a bypass vs. resection of the pouch.59,60 In the short term there are no differences, although in the long term, quality of life studies are better in patients with pouch resection, so whenever possible the latter technique is recommended instead of bypassing the pouch.

Resection of the ileal pouch can be completed with an end ileostomy or with the performance of a continent ileostomy (Kock type). Pouchectomy is a procedure with a 60% perioperative morbidity rate and a 1.5% mortality rate.61 Complications are usually septic in the acute period (10%). The most common ones are chronic, with impaired perineal wound healing (chronic perineal sinus) in up to 40%, intestinal occlusion (15%), perineal pain, or sexual or urinary dysfunction. It is important to remember that a systematic review concluded that there are no differences in quality of life between operated patients with a pouch and patients with definitive ileostomy.62

Treatment of cuffitisAlthough this condition is not unusual in operated patients, there are hardly any data or studies on its management, although only the treatment of symptomatic patients is recommended. In a series of 14 patients treated with mesalazine suppositories, both clinical and endoscopic improvement were observed.63 In another series that included 120 patients with cuffitis who were monitored for 6 years, 40 (33%) of them responded adequately to mesalazine and steroids. Fifty-eight (48%) were refractory to both treatments. Among these, 19 actually had CD of the pouch and 14 had postoperative complications (fistulas and sinus).64 Therefore, topical mesalazine is the treatment of choice today, although in some patients therapeutic escalation to corticosteroids may be necessary and biological therapies may also even be necessary.

A distinction must be made between patients with conventional cuffitis, who tend to respond to the aforementioned treatments, and a subgroup of patients with cuffitis refractory to these treatments. Histology in these refractory cases may be different from that of UC and sometimes present ischaemia data,64 and cases of collagenous cuffitis have even been reported.65 Refractory chronic cuffitis unresponsive to medical therapy should be considered for transanal mucosectomy with advancement of the pouch or excision in intractable cases.66

Conflicts of interestMBA: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

IM-J: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

IR-L: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, Pfizer, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Tillotts Pharma, Roche, Faes Farma, Kern Pharma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Ferring, Dr. Falk Pharma, Adacyte and Otsuka Pharmaceutical.

FG: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: Instituto Danone, Biocodex Foundation, Pfizer Consumer Healthcare, Clasado, Sanofi, Ferring, Farmasierra Research/Clinical Trials: Abbvie, Takeda, Clasado, Novartis, Biocodex, Sanofi, Chiesi and Danon.

AG: scientific advice, research support and/or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Faes Farma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

MCh: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma and Tillotts Pharma.

JPG: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

BB: scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Takeda, Ferring, Otsuka, Amgen.

PN: support for research and/or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Kern, Faes, Ferring, Tillots and Otsuka.

Please cite this article as: Barreiro-de Acosta M, Marín-Jimenez I, Rodríguez-Lago I, Guarner F, Espín E, Ferrer Bradley I, et al. Recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) sobre la reservoritis en la colitis ulcerosa. Parte 2: Tratamiento. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2020.04.004

See related content at DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastre.2019.10.002https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2020.04.004