Pouchitis is a common complication in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients after total proctocolectomy. This is an unspecific inflammation of the ileo-anal pouch, the aetiology of which is not fully known. This inflammation induces the onset of symptoms such as urgency, diarrhoea, rectal bleeding and abdominal pain. Many patients suffering from pouchitis have a lower quality of life. In addition to symptoms, an endoscopy with biopsies is mandatory in order to establish a definite diagnosis. The recommended index to assess its activity is the Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI), but its modified version (PDAIm) can be used in clinical practice. In accordance with the duration of symptoms, pouchitis can be classified as acute (<4 weeks) or chronic (>4 weeks), and, regarding its course, pouchitis can be infrequent (<4 episodes per year), recurrent (>4 episodes per year) or continuous.

La reservoritis es una complicación frecuente en los pacientes con colitis ulcerosa tratados mediante una proctocolectomía total. Consiste en una inflamación inespecífica del reservorio ileo-anal, cuya etiología no se conoce aún por completo. Esta inflamación induce la aparición de síntomas como urgencia, diarrea, rectorragia y dolor abdominal, alterando la calidad de vida de los pacientes que la padecen. Para su diagnóstico, además de los síntomas, es necesario realizar una endoscopia con toma de biopsias. El índice recomendado para valorar su actividad es el Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI), aunque puede emplearse su forma modificada (PDAIm). De acuerdo a la duración de los síntomas, la reservoritis se clasifica en aguda (<4 semanas) o crónica (>4 semanas). Según su curso evolutivo se clasifica en infrecuente (<4 episodios/año), recurrente (>4 episodios/año) o de curso continuo.

In recent years we have witnessed a drastic change in the medical treatments available for the management of ulcerative colitis (UC). Their ultimate objective is to control inflammatory activity and with them it is hoped that quality of life can be restored and the natural history of the disease be modified. This also implies avoiding surgery in patients with disease which is resistant to medical treatment or even complications such as the development of colonic neoplasms. Despite multiple advances in the medical treatment of UC in recent years, between 10 and 35% of these patients require surgery due to inadequate response to treatment or due to the presence of dysplasia or neoplasia. Total proctocolectomy (performed over 3 sessions) with ileo pouch-anal anastomosis is the surgical procedure of choice.1 This procedure was described in 1978 by doctors Parks and Nicholls.2 The objective of this intervention is to resect the colon, preserving continence and avoiding permanent ostomy. Currently, it is more frequently carried out in 2 sessions, but it is also possible to do it in 3. Although, after undergoing this surgery, a large number of patients enjoy improved quality of life and, as is logical, the risk of colon neoplasia is reduced, we cannot say that in all patients operated UC means "cured" UC. The reason for this statement is that there are many complications that may occur after the surgical procedure, including sepsis, obstruction due to stenosis, faecal incontinence, ischaemia of the pouch, cuffitis or inflammation of the rectal cuff, fistulisation that may or may not be accompanied by the appearance of de novo Crohn's disease (CD) or, most frequently, pouchitis.3

Pouchitis consists of an inflammation of the ileo-anal pouch, whose aetiology is not yet fully known. This inflammation prompts the appearance of symptoms such as urgency, diarrhoea, rectorrhagia and abdominal pain. Although it is a frequent situation in normal practice, there are no defined criteria for its diagnosis and correct classification. In any case, an endoscopic study should be carried out in patients with symptoms indicative of this complication to demonstrate endoscopic or histological inflammatory changes, without which the definitive diagnosis of pouchitis cannot be established.

Why are pouches created?The surgical treatment of UC is based on the resection of the target organ of the disease: the colon and rectum. This translates into a total proctocolectomy. Although there are authors who defend the possibility of using a more conservative procedure, such as total colectomy with ileo-rectal anastomosis,4 this technique is only performed in a small number of patients, due to the high risk that the disease remains active in the rectum. Once the total proctocolectomy is completed, intestinal transit can be restored in 2 ways: a terminal ileostomy or an ileo-anal anastomosis in the form of an ileal pouch. Numerous articles have been published over the past few decades in which it is shown that creating an ileal pouch instead of a terminal ostomy would be the best option, especially in young patients. The functional results are generally very acceptable, with a mean number of bowel movements ranging from 4 to 6 during the day and 1–2 at night, virtually non-existent faecal urgency and without the problems derived from the permanent use of an ileostomy. Different types of ileal pouches have been designed, with the most frequently used pouch being the J pouch (double ileal loop), but S (triple ileal loop) and W (quadruple ileal loop) pouches can also be used. The type of pouch indicated will depend on certain variables, such as the indication of the colectomy, the performance of mucosectomy and the technical possibility of performing each of them according to the characteristics of the patient (mainly, according to the body mass index, the length of the mesentery and histology of previously obtained samples). Evidence has shown that whenever possible, the J reservoir should be used due to its simplicity and good results.5

The results of total proctocolectomy with pouch are excellent and more than 90% of the patients operated on with this technique report that they would opt to have the surgery again when they feel better than when they had active UC. Patients should be notified and warned that this surgical technique has been associated with acute complication rates of 28%–58% and chronic complications of 52%,6 as well as a figure of up to 15% of pouch failure.7 However, in a generally young population, it is common for patients to prefer the option of being treated with an ileal pouch and thus not being carriers of a definitive ileostomy.

In pouchitis common?The incidence of pouchitis varies between 7 and 45% of patients treated with total proctocolectomy with ileo-anal anastomosis and pouch construction.6,8 Annual incidence can reach 40%.9 This risk seems to increase progressively from the time the operation takes place, with a prevalence of 25, 32%, 36, 40 and 45% 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years after the operation, respectively.8 This risk is increased in those patients with associated primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), in whom it can reach 80% 10 years after the operation.10

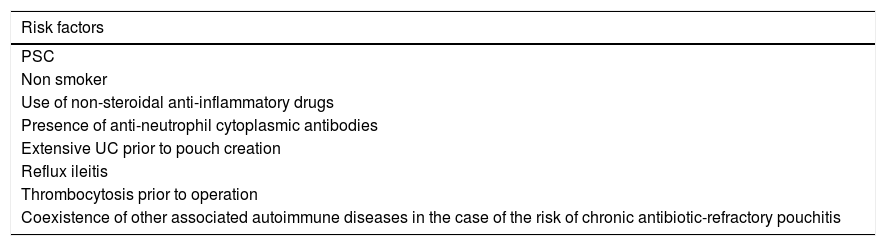

Multiple risk factors (clinical, serological and endoscopic) have been identified for developing pouchitis.6,11–17 The main ones are listed in Table 1.

Risk factors for the development of pouchitis.

| Risk factors |

|---|

| PSC |

| Non smoker |

| Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Presence of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies |

| Extensive UC prior to pouch creation |

| Reflux ileitis |

| Thrombocytosis prior to operation |

| Coexistence of other associated autoimmune diseases in the case of the risk of chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis |

Therefore, we can conclude that pouchitis is a frequent complication, and may occur in up to 45% of patients 5 years after surgery.

What is the pathophysiology of pouchitis?After the construction of the ileal pouch, the mucosa progressively acquires an appearance more similar to that of colonic mucosa (colonic metaplasia). This process involves flattening of the villi and hypertrophy of the crypts. It is also common to find a chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the reservoir associated with the metaplasia process,18,19 but pouchitis is only considered only considered to be present when there are acute inflammatory changes, such as polymorphonuclear infiltrate.20 The exact aetiology of pouchitis is unknown, but studies that have analysed its pathogenesis have consistently found alterations such as dysbiosis or bacterial overgrowth. So intestinal microbiota seems to play an essential role in the appearance of this complication.20 These findings are supported by the response to antibiotics and probiotics, both in acute and chronic pouchitis, and in the fact that inflammation appears mainly when intestinal transit is reconstructed.21

IschaemiaIt has been postulated that there may be some degree of ischaemia that can contribute to the onset of pouchitis. This is because it has been observed that the reservoir has lower blood supply compared to the colon under normal conditions.22 Despite this, ischaemia is probably not the main mechanism of pouchitis, since the procedure is the same as that performed in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), with a very different risk of occurrence of this complication between both groups

Genetic factorsEthnicity also seems to influence the risk of developing pouchitis, although the data is very limited. Both Ashkenazi Jews and subjects originating in South Asia seem to have an increased risk.23 The most relevant genetic associations have been found with variants of NOD2 (rs2066847, NOD2insC and 1007fsCins), although it is possible that other genetic polymorphisms such as IL-1RN*2, IL-1RN*1, TNF*1, ATG16L1, U6, JAK2, TNFSF15, NOD2, S100Z, TLR9 and CD14 also influence its pathogenesis.24–29

Immunological factorsInnate immunity shows alterations that are possibly secondary to increased exposure to bacterial antigens, which may be related to changes that have been observed in the secretion of intestinal mucus in these patients. When analysing the genetic expression in reservoirs of patients with UC and FAP without signs of inflammation, important differences were found that mainly affected molecules involved in the innate immune response.30 Among the possible genes involved in the pathophysiology of this complication are the Charcot-Leyden crystal protein (galectin-10), ITPRIPL2 and COG5.30

Increased levels of CD4+ lymphocytes, CD4+/CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes and CD8+/HLA-DR + lymphocytes have been reported in the mucosa of the reservoir.31 In addition, it seems that B lymphocytes may be involved in its pathogenesis, having also found CD40+ and CD40L + leukocytes, as well as CD19+CD138+ plasma cells.32,33

In summary, the pathogenesis of pouchitis involves an altered immune response of the reservoir in subjects with a certain genetic predisposition, but also the close involvement of the microbiota.

How should pouchitis be diagnosed?After a total proctocolectomy and reconstruction of a reservoir, the average number of movements in patients without pouchitis is between 4 and 8, with around 700 ml of semi-liquid stools per day, much higher than the average in healthy subjects.34 A combination of clinical symptoms, endoscopic and histological findings is necessary to establish the diagnosis of pouchitis, as well as to establish the differential diagnosis with other entities that will be reviewed later.35

What symptoms should make us suspect pouchitis?The characteristic symptoms of a patient with pouchitis are the presence of diarrhoea, abdominal pain, faecal urgency and tenesmus, fever, incontinence and it can sometimes be accompanied by extra-intestinal manifestations.36 When patients present with rectal bleeding, although it may be present in some cases of pouchitis, we should consider cuffitis or inflammation of the remnant of the remaining rectum after surgery. These symptoms, however, are not specific to pouchitis, so the presence of compatible endoscopic and histological findings is necessary to establish the definitive diagnosis and thus be able to rule out, for example, irritable reservoir syndrome. The severity of symptoms does not always correlate with the degree of endoscopic and histological inflammation.

What is the role of endoscopy in the diagnosis of pouchitis?Reservoir endoscopy is a fundamental technique to establish the diagnosis of pouchitis. During the procedure, it is essential to identify, describe and document in an image all the structures of the reservoir: afferent and efferent loop, reservoir, anastomosis and rectal remnant or cuff. It is recommended that, in general, the first endoscopic review should be performed 6–12 months after the closure of the ileostomy to evaluate the reservoir in order to rule out stenosis and take biopsies, examine both ileal loops and the preserved rectal mucosa or cuff, if it exists. Endoscopic findings of patients with pouchitis include: oedema, granularity, friability, loss of vascular pattern, haemorrhage and ulceration.37

It should be taken into account that the presence of small ulcers in the suture lines is frequent and does not indicate pouchitis or CD. In inflammatory processes it is important to describe the distensibility and extent of inflammation, as well as the existence of pre-reservoir ileitis, cuffitis, stenosis or fistulas. The distribution of lesions in the reservoir can inform us about their aetiology. Autoimmune disorders and reservoir infections associated with IgG4 often have a long inflamed segment in the afferent loop in addition to diffuse involvement of the reservoir. The asymmetric distribution of inflammation present only in the distal half of the reservoir body, with distinct demarcation with the non-inflamed area, is suggestive of ischaemic aetiology.38

It is recommended to take between 4 and 6 biopsies of the reservoir, whether macroscopic inflammation is observed (for differential diagnosis) or not (in mild forms, the endoscopic appearance may be normal). Furthermore, although there is no consensus in this regard, some authors also recommend performing 4–6 biopsies of the pre-reservoir ileum even though their endoscopic appearance is normal. Taking biopsies can detect the presence of granulomas, ischaemia, cytomegalovirus inclusions and dysplasia. The biopsy of ulcers located in the suture lines should be avoided, since foreign body granulomas can be confused with CD data.39

HistologyThe most typical histological findings of active pouchitis are: acute inflammation with infiltration of neutrophils, cryptic abscesses or mucosal ulceration often associated with chronic changes such as villus atrophy, cryptic distortion and chronic inflammatory infiltrate.19

Laboratory testsCoproculture studies can help in detecting superinfections such as Clostridium difficile (C. difficile). On the other hand, the role of faecal markers such as calprotectin has also been studied as a measure to diagnose a pouchitis.40,41 Therefore, these faecal biomarkers can be useful in the early diagnosis of pouchitis, with their measurement being recommended annually in asymptomatic patients.

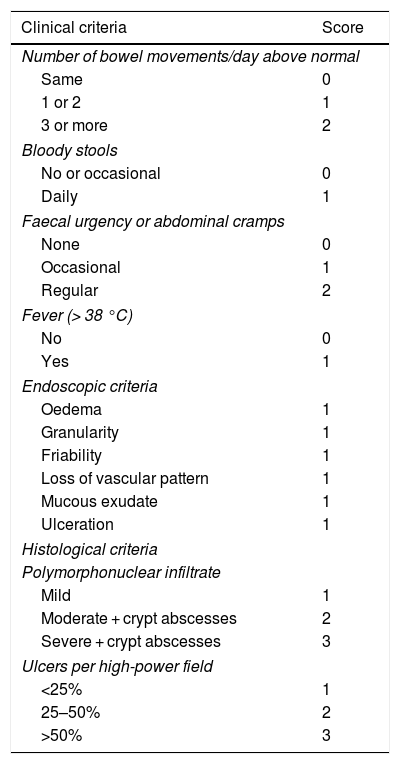

What activity index should we use?Once pouchitis is diagnosed, to assess the response to treatments it will be necessary to know and quantify the disease activity. The Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI) is the index most used in clinical trials. It is a numerical scale that quantifies the severity of pouchitis and consists of 3 sub-indexes: clinical, endoscopic and histological.42 The diagnosis of pouchitis corresponds to a score ≥ 7. The PDAI, however, it is not commonly used in clinical practice given the complexity of its calculation. Thus, to try to simplify the calculations, a modified index, the mPDAI, has been developed, which only includes clinical and endoscopic criteria, with a good correlation with the PDAI, so that an mPDAI ≥5 would be diagnostic of pouchitis (Table 2).43

Pouchitis disease activity index.

| Clinical criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| Number of bowel movements/day above normal | |

| Same | 0 |

| 1 or 2 | 1 |

| 3 or more | 2 |

| Bloody stools | |

| No or occasional | 0 |

| Daily | 1 |

| Faecal urgency or abdominal cramps | |

| None | 0 |

| Occasional | 1 |

| Regular | 2 |

| Fever (> 38 °C) | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

| Endoscopic criteria | |

| Oedema | 1 |

| Granularity | 1 |

| Friability | 1 |

| Loss of vascular pattern | 1 |

| Mucous exudate | 1 |

| Ulceration | 1 |

| Histological criteria | |

| Polymorphonuclear infiltrate | |

| Mild | 1 |

| Moderate + crypt abscesses | 2 |

| Severe + crypt abscesses | 3 |

| Ulcers per high-power field | |

| <25% | 1 |

| 25–50% | 2 |

| >50% | 3 |

Taken from Sandborn et al.42.

We can conclude that in order to establish the diagnosis of pouchitis, the presence of compatible clinical symptoms, endoscopic and histological findings is required.

With what entities should we make the differential diagnosis of pouchitis?The diagnosis of pouchitis is often not straightforward, so all specialists involved in the management of these patients should be able to recognise the different entities that can affect the reservoir and cause pouchitis. The following are the ones that are considered most important:

- –

CD of the reservoir.

- –

Infectious pouchitis.

- 1

C. difficile: this complication can occur in up to 2.6% of cases of pouchitis, and the risk is increased with respect to those patients with a reservoir affected by polyposis syndrome.44

- 2

Cytomegalovirus: especially consider in those patients under immunosuppressive treatment, although its frequency is not very high.45

- 3

Other microorganisms such as Clostridium perfringens, Campylobacter and some Enterococcus or Escherichia coli.

- 1

- –

Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- –

Eosinophilic pouchitis: Although eosinophils are associated with an allergic or parasitic immune response, in some patients it is possible to observe an inflammation in which eosinophils predominate in the mucosa of the reservoir in the absence of other known triggers.

- –

Autoimmune pouchitis: in the event of chronic antibiotic refractory pouchitis, IgG4 determination should be performed, since situations of reservoir inflammation have been described that could be framed within the spectrum of IgG4-associated disease.46,47

- –

Ischaemia: asymmetric inflammation of the reservoir is characteristic and is usually associated with antibiotic resistance.38 It should be considered in re-operated patients after the construction of the reservoir and with a history of postoperative portal thrombosis.

- –

Cuffitis, caused by an inflammation of the remnant of rectal mucosa.

- –

Irritable reservoir syndrome.

- –

Bacterial overgrowth.

- –

Reservoir stenosis.

- –

Difficulty emptying the reservoir.

- –

Dysfunction of the pelvic floor

- –

Afferent loop syndrome.

- –

Other malabsorption syndromes such as celiac disease or bile salt malabsorption.

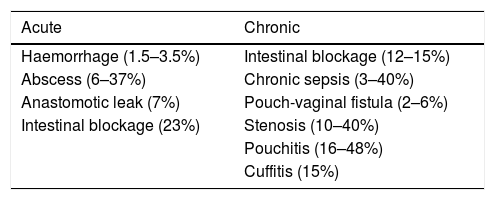

Making an ileal reservoir is a complex but standardised procedure. The index of surgical complications is not negligible (15%).48 This high rate of complications can arise from the surgical procedure or from the UC itself. Regarding the complexity of the procedure, the results can be improved and the complications reduced if the surgery is indicated and performed by surgeons trained and dedicated to colorectal surgery and with a high volume of procedures per year For these reasons it is recommended that it be performed in centres where the team is experienced in treating patients with inflammatory bowel disease. On the other hand, the results in the short and long term are very different in patients with a basic diagnosis of UC when compared with non-inflammatory indications such as FAP.49 Pouch complications can be divided into 2 groups: acute and chronic (Table 3).

Undoubtedly, septic complications are the most frequent complications in ileal reservoir surgery, excluding pouchitis. These complications can be acute (abscess, suture failure, fistula) or chronic (fistulas, chronic sinus). In the immediate period, sepsis appears in between 5 and 19% of patients.50 The incidence of septic complications increases with the presence of risk factors, such as the diagnosis of CD, greater severity of UC, steroid use, treatment with biological products, malnutrition, hypoalbuminemia, anaemia, hypoxemia and inexperience of the surgeon, among others.51 Some technical aspects continue to divide opinion regarding their relationship with the increase in the incidence of septic complications: mucosectomy, manual vs mechanical anastomosis, derivative ileostomy or intubation of the reservoir in the immediate postoperative period. On the other hand, it has been shown that the presence of septic complications in the postoperative period does adversely affect the long-term function of the reservoir, either with or without the ultimate failure of the reservoir.52

What is the prognosis of the patient with a reservoir?The cumulative probability of reservoir failure and the need for definitive ileostomy and excision of the reservoir ranges between 3 and 15% in large series.53,54

Several studies have focused on finding the risk factors of poor evolutionary prognosis in patients with an ileo-anal pouch. Some groups, such as the one from Cleveland, have even created a nomogram applicable in clinical practice to estimate the risk of long-term reservoir failure. The factors considered were smoking, reservoir duration, basal pouchitis and pre- and post-operative use of biologic products.55

Another circumstance to consider regarding the prognosis of patients is the presence of pre-pouch ileitis. This finding has been associated with the diagnosis of CD of the pouch, and this in turn with its risk of failure. This entity is uncommon, affecting 6% of patients.56 Initially it was considered diagnostic or a risk factor for development of CD of the pouch. However, in a study of 31 patients diagnosed with pre-pouch ileitis, only 2 patients were diagnosed with CD of the pouch.57 In conclusion, this rare entity seems to be associated with pouchitis, with the risk of long-term pouch failure and does not have to be a precursor to CD.

Does a pouch improve the quality of life of patients?The objective of UC surgery has evolved over time from reducing mortality to reducing morbidity and improving patient quality of life. However, performing a proctocolectomy with a pouch does not imply the complete restoration of intestinal function.

There are several studies that evaluate the functional results of the ileo-anal pouch. The frequency of defecation considered normal in patients with a pouch usually ranges between 4–7 movements per day and 1–2 per night.58 In general, data from published studies conclude that bowel function with a pouch may be adequate59,60; however, other studies find a considerable incidence of intestinal dysfunction associated with the creation of the pouch.61 Some of the factors related to a worse functional evolution of the pouch are age over 50 years, the existence of extraintestinal manifestations, stenosis and anal pain.62 In addition, with the passage of time, the possibility of faecal incontinence increases to nearly 21% of nocturnal involvement at 2 years after surgery.58

This type of intervention can be associated with sexual dysfunction and fertility problems in both men and women. The presence of impotence and retrograde ejaculation has been described in 0–3% of operated men.63 In women, excessive vaginal discharge (58%), dyspareunia (38%) and decreased vaginal proprioception (25%) are some of the disorders described. A meta-analysis of complications associated with pouches concluded that the overall incidence of sexual dysfunction was 3.6%.3

Infertility associated with pouch surgery is determined by structural or functional problems in the reproductive organs. It is estimated that the possibility of pregnancy in these patients is 20% lower than that in patients with UC who receive medical treatment.64 Therefore, this is a relevant factor to be considered with women of childbearing potential and without offspring prior to surgery.

Most studies that assess quality of life after UC surgery have a moderate or low methodological quality. A review in this regard included 33 studies with a total of 4790 patients and, of these, only 3 studies could be considered of high quality.65 The quality of life in relation to the health of patients assessed at 12 months after surgery improved and was comparable to that of the general population, although the heterogeneity of the studies was high. On the other hand, most of the studies that assess postoperative quality of life have used scoring instruments such as the SF36. A study specifically aimed at assessing quality of life found that 61% of patients had a worse quality of life than the general population.66 In addition, it found that a preoperative age of over 35 years was the best predictor of poor quality of life after surgery.

We can conclude with respect to quality of life that we have data that support that it is similar to that of the general population, but this is only maintained in patients with an adequate pouch function.

How should we control patients with reservoirs?There are different ways to classify pouchitis according to various parameters. Depending on the duration of symptoms, pouchitis is classified as acute (less than 4 weeks) and chronic (more than 4 weeks). According to response to antibiotics, it can be classified as: antibiotic-responsive, antibiotic-dependent or antibiotic-refractory. According to its evolutionary course, we classify it as infrequent (less than 4 episodes/year), recurrent (more than 4 episodes/year) or continuous.

The natural history of the disease is variable. 39% of patients with acute pouchitis will never experience recurrence, while 61% of patients will have at least one recurrence.36 It is estimated that between 5–19% of patients with acute pouchitis will develop refractory pouchitis or a frequently recurrent form of the disease. As for the follow-up of patients, it must be clinical, analytical and endoscopic.

The recommended laboratory test for the follow-up of a patient with a pouch is faecal calprotectin, due to its predictive value, its elevation being verified 2 months before the clinical onset of pouchitis. In the case of calprotectin, the cut-off value of 56 μg/g showed a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 84% to predict pouchitis.67

Endoscopy of the pouch is, without doubt, the imaging technique of choice in the follow-up of patients with a pouch. We have data that show a poor correlation between symptoms and endoscopic and histological findings in patients with pouchitis. Therefore, endoscopic reservoir monitoring is also important in asymptomatic patients; it allows us to detect sustained inflammation that can condition the pouch failure in the long term,68 early diagnosis of pouchitis or CD of the pouch, facilitating the prevention of progression to chronic pouchitis or the development of stenosis or fistulas.

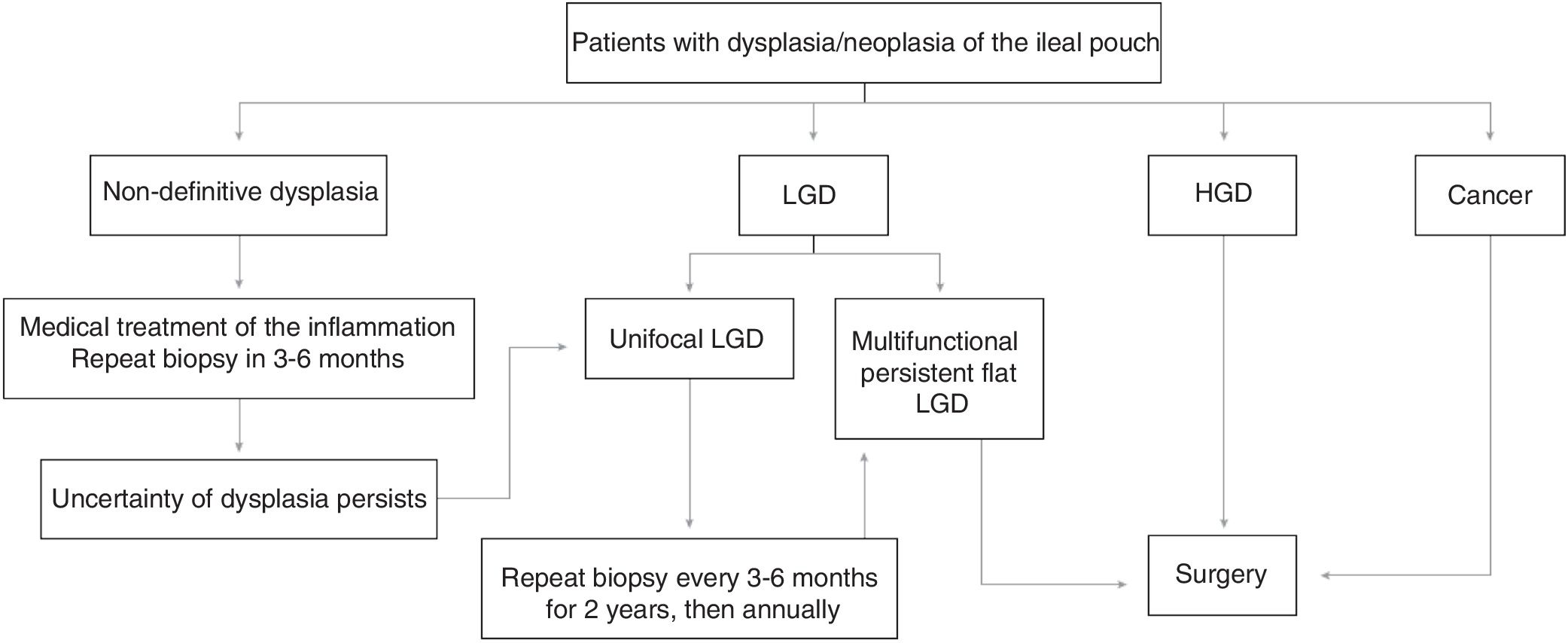

The other aspect for which endoscopic follow-up of patients with a pouch is recommended is the possibility of developing dysplasia or neoplasia. The appearance of adenocarcinoma, mostly, but also of lymphomas and squamous cell carcinoma in the pouch has been described. In the Fazio series in Cleveland,69 the follow-up analysis of 3707 people with a pouch found an incidence of cancer/dysplasia of 2.6% (97 patients), with a cumulative incidence of neoplasia at 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 years of 0.9, 1.3, 1.9, 4.2 and 5.1%, respectively. The location of adenocarcinoma of the pouch is usually in the anal transition zone (65%), and less frequently in the body of the reservoir (19%), both (5%) or in the afferent and efferent bowel loops (2%). Regarding dysplasia, some series describe a prevalence of 1.9% in the anal transition zone and 4.2% in the reservoir body. This figure attracts attention because the area where neoplasms most frequently settle is in the anal transition zone. These data suggest that dysplasia of the reservoir has less clear consequences than that of the transitional zone, and its prevalence data are very variable among the different studies.70,71

It has been discussed whether the surgical technique used for pouch creation has an influence on the risk of subsequent neoplasia development. Manual suturing with mucosectomy of the anal transition zone is technically more difficult but decreases, without completely eliminating, the risk of neoplasia. In fact, 18% of pouch neoplasms (anal transition zone) in a series had a previous history of mucosectomy.72 Regarding other risk factors described, the following are particularly notable: preoperative diagnosis of dysplasia or cancer associated with UC (connected with an increased risk of reservoir cancer of 4.4 and 15 times, respectively), long-term UC (>10 years), PSC,73 family history of colon cancer and reflux ileitis. It has been estimated that the risk of developing dysplasia in the transition zone is 10% if there was dysplasia and 25% if there was cancer in the colectomy piece.74 Reservoir neoplasia is diagnosed by pouchoscopy, with 4–6 biopsies of the transitional area and 2–6 of the afferent loop and the body of the reservoir being recommended. Dysplasia or cancer can be detected in flat mucosa, ulcerated lesions or masses.75

The prognosis of reservoir cancer is generally bad, with a 5-year survival rate of 49%, which supports the need for monitoring to try to diagnose it early. However, the prevalence and incidence of this type of tumour is low, so some authors are not in favour of routine monitoring in all patients, but only in patients with risk factors. The positioning of different societies in this regard varies. The British Society of Gastroenterology, in its guidelines published in 2010, considers high-risk patients as those with prior rectal dysplasia, dysplasia or cancer at the time of surgery or PSC, and for them it recommends annual endoscopy; the rest of the patients should be reviewed endoscopically every 5 years. The 2017 ECCO guidelines stratify as high-risk patients those with dysplasia or cancer at the time of surgery, PSC or persisting pouchitis, recommending in these situations annual monitoring with endoscopy of the pouch. However, in patients without these risk factors, it does not consider that there is evidence to support endoscopic monitoring.1

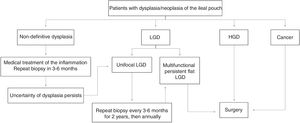

From all of the above we can conclude that endoscopic monitoring in patients with a pouch is recommended and should be started 10 years after the diagnosis of UC, regardless of when the pouch was created. We suggest that high-risk patients (a history of neoplasia or dysplasia before surgery) should be monitored endoscopically on an annual basis, those with intermediate risk (other risk factors: chronic pouchitis, cuffitis, PSC, family history of colon neoplasia) between 1–3 years and those without risk factors, every 5 years. In the event of dysplasia being detected during control pouchoscopies, we suggest using the tracking algorithm of Fig. 1, based on the recommendations of the Cleveland group.76

CuffitisThe 2 surgical techniques used in the creation of a pouch are the mucosectomy of the anal transition zone with hand-suturing or stapling preserving the anal transition zone. In this second technique, the rectal remnant or cuff of 1.5–2 cm of columnar epithelium remains in a location proximal to the anal transition zone. This implies less technical difficulty for the surgeon and better functionality for the patient. However, it carries a risk of developing inflammation of the area (cuffitis) or dysplasia of the residual rectal mucosa or anal transition zone.77,78 However, cuffitis has also been described in patients with manual suturing and mucosectomy, since it is very difficult to ensure that it is complete and there are no residual islets of mucosa.79

By cuffitis, therefore, we understand the inflammation or recurrence of UC in the remaining rectal mucosa. Some patients with endoscopic and histological inflammation in the cuff are asymptomatic. Overlapping symptoms of pouchitis, CD of the pouch and irritable reservoir syndrome may be: diarrhoea, abdominal pain, urgency and incontinence, although haematochezia is more frequent in patients with cuffitis.80 Furthermore, cuffitis and pouchitis can coexist in the same patient. There are not many studies about the incidence and prevalence of this entity, although some of them estimate its prevalence in 7% of patients with an ileo-anal pouch.81 Diagnosis is established by endoscopy and histology, showing inflammation of the residual rectal mucosa, with erythema, friability, ulceration, nodularity and neutrophilic infiltrate. Some authors have proposed a cuffitis activity index adapted from the PDAI.82

Conflict of interestsMBA: scientific consultancy, research support or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Vifor Pharma.

AGC: scientific consultancy, research support or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Faes Farma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Vifor Pharma.

IRL: scientific consultancy or training activities: MSD, Pfizer, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Tillotts Pharma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Ferring, Dr. Falk Pharma and Otsuka.

IMJ: scientific consultancy, research support or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Vifor Pharma.

LS: Scientific consultancy, research support or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma.

JPG: scientific consultancy, research support or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Vifor Pharma.

BB: scientific consultancy, research support or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Takeda, Ferring, Otsuka, Amgen.

PNM: research support or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Kern, Faes, Ferring, Tillots, Otsuka.

Please cite this article as: Barreiro-de Acosta M, Gutierrez A, Rodríguez-Lago I, Espín E, Ferrer Bradley I, Marín-Jimenez I, et al.; en representación de GETECCU. Recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) sobre la reservoritis en la colitis ulcerosa. Parte 1: epidemiología, diagnóstico y pronóstico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:568–578.s