Collaboration between Primary Care (PC) and Gastroenterology in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is crucial to provide high-quality healthcare. The aim of this study is to analyse the relationship between PC and gastroenterologists at a national level in order to identify areas for improvement in the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and how to address them, with the aim of subsequently developing concrete proposals and projects between SEMERGEN and GETECCU.

MethodsDescriptive, observational, cross-sectional study, was carried out using an anonymous online questionnaire between October 2021 and March 2022.

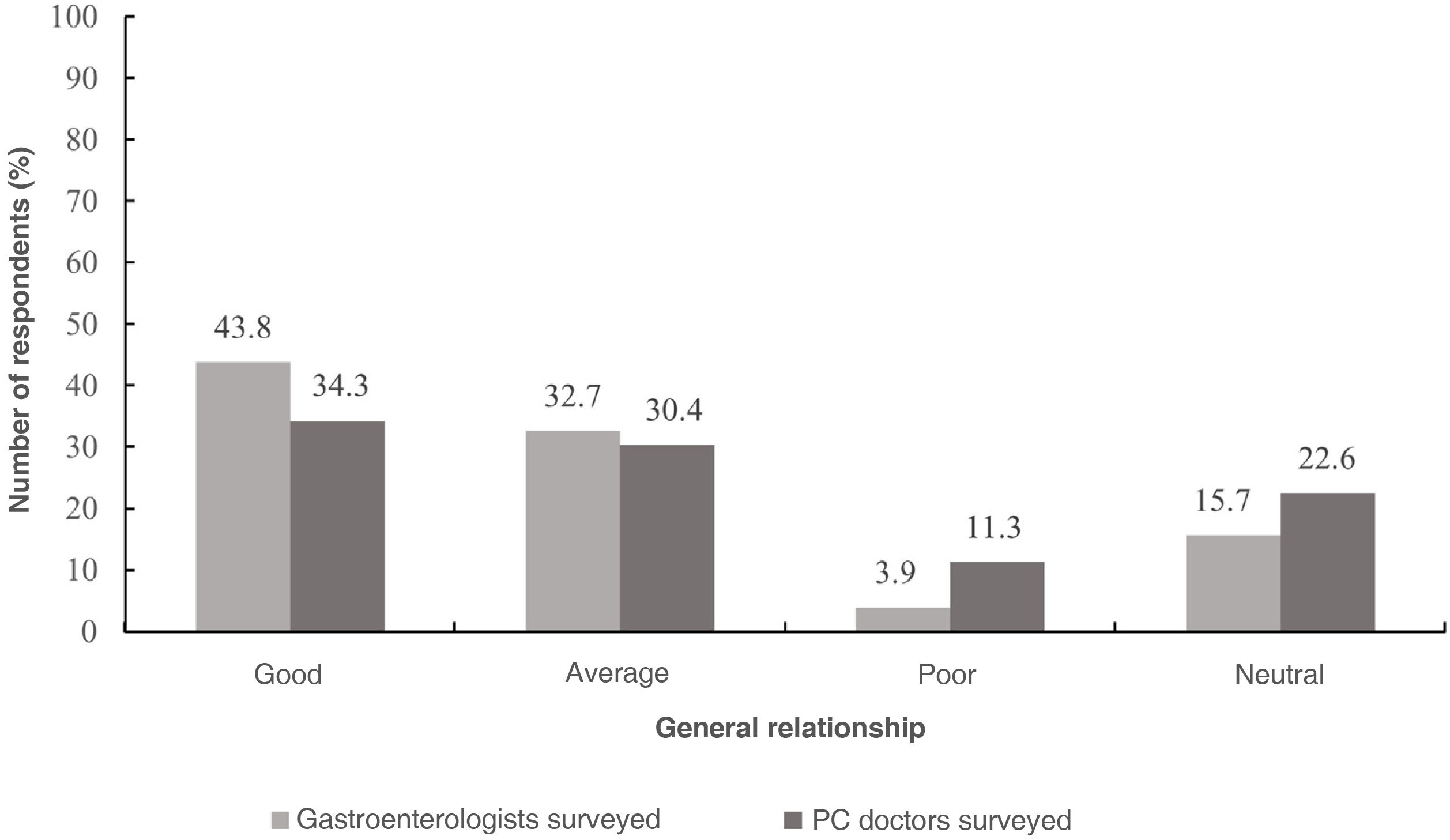

ResultsA total of 157 surveys from Gastroenterology and 222 from PC were collected. 43.8% and 34.3% of gastroenterologists and family practitioners, respectively, considered that there was a good relationship between the units. The level of knowledge from family practitioners regarding different aspects of IBD out of 10 was: clinical 6.67±1.48, diagnosis 6.47±1.46, treatment 5.63±1.51, follow-up 5.53±1.68 and complications 6.05±1.54. The perception of support between both units did not exceed 4.5 on a scale from 0 to 10 in either of the surveys. The most highly voted improvement proposals were better coordination between the units, implementation of IBD units, and nursing collaboration.

ConclusionThere are deficiencies in the relationship between PC and Gastroenterology with special dedication to IBD that require the efforts of the scientific societies that represent them for greater coordination with the development of joint protocols and agile, fast, and effective communication channels.

La colaboración entre Atención Primaria (AP) y Gastroenterología en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) es crucial para ofrecer una atención médica de alta calidad. El objetivo del presente estudio es analizar, en el ámbito nacional, la relación entre AP y los gastroenterólogos con el objetivo de conocer los aspectos de mejora en el manejo de pacientes con EII y cómo poder implementarlos, para así desarrollar posteriormente propuestas y proyectos concretos entre SEMERGEN y GETECCU.

MetodologíaEstudio descriptivo, observacional y transversal, realizado mediante cuestionario online anónimo entre octubre de 2021 y marzo de 2022.

ResultadosSe recopilaron un total de 157 encuestas de Gastroenterología y 222 de AP. El 43,8% y el 34,3% de los gastroenterólogos y médicos de familia, respectivamente, consideraron tener una buena relación. El grado de conocimiento de los médicos de familia sobre diferentes aspectos de la EII (puntuado sobre 10) fue: aspectos clínicos 6,67±1,48, diagnósticos 6,47±1,46, terapéuticos 5,63±1,51, de seguimiento 5,53±1,68 y complicaciones 6,05±1,54. La percepción del apoyo y soporte entre ambas unidades no superó el 4,5 en una escala de 0 a 10 en ninguna de las encuestas. Las propuestas de mejora más votadas fueron: mayor coordinación entre especialistas, implantación de unidades de EII y colaboración de enfermería.

ConclusiónExisten deficiencias en la relación entre AP y Gastroenterología con especial dedicación a la EII que requiere de los esfuerzos de las sociedades científicas que los representan para una mayor coordinación, con elaboración de protocolos conjuntos y medios de comunicación ágiles, rápidos y efectivos.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises a set of chronic inflammatory disorders of unknown aetiology that affect the gastrointestinal tract. They are mainly classified into Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), diseases of unknown aetiology that occur with periods of activity and remission.1,2 The incidence in Spain is 16.2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants/year and has experienced a significant increase in recent years, placing Spain among the countries with the highest incidence.3,4 Although IBD is most often diagnosed in young people, it can occur at any age.3 The clinical presentation of IBD is variable and this can delay its diagnosis significantly.3,5,6 IBD is associated with significant morbidity and disability, and may result in incapacity for work or hospitalisation of the patient.7–9

Due to its chronic nature, IBD requires follow-up by health professionals specialising in this pathology.10 This need for continuous follow-up, along with its high incidence, entails a significant cost for healthcare systems and, among gastrointestinal diseases, IBD is currently one of those commanding the highest level of expenditure.11,12

Diagnosis begins with a visit by the symptomatic patient to his or her family doctor. Usually, if there is suspicion based on the clinical history and the physical examination supported by laboratory tests, the patient is referred to the Gastroenterology department, responsible for making the definitive diagnosis by performing endoscopic and radiological tests. As the symptoms of the disease are heterogeneous, variable and easily confused with other gastrointestinal disorders, especially functional ones, the role of Primary Care (PC) is essential when identifying cases with high clinical suspicion, as it is the patient’s first point of contact after the onset of symptoms.13

One of the objectives of family doctors in IBD is to avoid long delays in diagnosis that aggravate the disease and to quickly and reliably identify patients who should be referred to the Gastroenterology IBD unit. In addition, they screen patients who require an urgent referral from those who, due to their good general condition, can follow standard procedures.13 However, the general relationship between PC and Gastroenterology specialists takes place in different contexts, all of them dynamic and, some, rapidly changing. The Spanish health system is very heterogeneous, and there are significant structural, organisational and even budgetary inequalities between autonomous communities.14 In addition, one of the most relevant challenges in PC and Gastroenterology is overburdened healthcare, which leads to a deterioration in quality and working conditions. All these factors influence the relationship between the different levels of care, which means that the opportunities for interaction tend to be insufficient.15

Due to the close and ongoing relationship between IBD patients and healthcare professionals, high-quality healthcare can optimise outcomes and improve patients’ quality of life.10 Thus, the Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria [Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians] (SEMERGEN) and the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa [Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] (GETECCU) are promoting the search for areas of collaboration in the management of patients with IBD. This study aimed to gain information on the opinion and experience of PC and Gastroenterology specialists in managing patients with IBD to identify areas for improvement and develop future joint projects.

Participants and methodsStudy designA cross-sectional study was carried out through an online survey targeted towards gastroenterologists and family doctors. Two different surveys were designed, one for each specialty. The preliminary surveys were generated by the project coordinators based on a literature review. Members of the boards of directors of the scientific societies of GETECCU and SEMERGEN subsequently evaluated them. The surveys were anonymous, and the responses were recorded through the Survey Monkey® online survey system (Menlo Park, California, USA) with a closed and structured questionnaire.

On the one hand, the survey for gastroenterologists was divided into five blocks with a total of 23 questions: block 1: sociodemographic data (sex, age, an autonomous community of residence, hospital affiliation, years worked as a gastroenterologist, work in an IBD unit, type of healthcare provided); block 2: level of knowledge about clinical practice in PC where access to calprotectin, ultrasound, colonoscopy or bone density testing is evaluated; block 3: relationship and interaction with PC (type, satisfaction, training activities, support received); block 4: diagnosis and management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including the definition of responsibilities, and block 5: improvements in daily practice for the management of patients with IBD.

The survey for family doctors was divided into five blocks with a total of 24 questions: block 1: sociodemographic data (sex, age, autonomous community of residence, workplace); block 2: level of knowledge about different IBD-related aspects such as clinical symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, follow-up and preventive activities, and complications; block 3: relationship and interaction with Gastroenterology (type, satisfaction, training activities, support received); block 4: diagnosis and management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including the definition of responsibilities, and block 5: improvements in daily practice for the management of patients with IBD.

For the responses to both surveys, scales from 0 to 10 were used (0 representing the lowest possible score and 10 the maximum), except for questions 20 and 21 of block 4 of the survey for gastroenterologists, where a scale from 0 to 5 was used (0 representing the lowest possible score, and 5, the highest). Closed-ended answers were also included, in which the respondent had to choose between the different options. Both surveys are attached to the supplementary material (Appendices A and B).

Selection of participants and launch of the surveyGiven the characteristics of the survey and its objectives, convenience sampling was carried out using the list of GETECCU and SEMERGEN members, inviting them to respond to the survey. This was launched on 25 October 2021 for gastroenterologists and on 13 December for family doctors via email. A reminder was sent on 21 February 2022 to boost the response rate. Both processes were closed on 1 March 2022.

This study was carried out in full compliance with the principles established in the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki regarding medical research in human beings and in accordance with the applicable regulations on Good Clinical Practices.

Statistical analysisData analysis was carried out using the Stata 12® statistical program (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). A descriptive analysis of the data was performed. The quantitative variables are described with the mean and standard deviation (SD), and the qualitative variables by frequency and percentages.

ResultsThe survey was emailed to members of GETECCU and SEMERGEN and was filled in by 157 gastroenterologists and 222 family doctors, representing 14% and 3% of the total number of members, respectively.

Results of the surveys of the Gastroenterology participantsMost of the respondents were women (68.8%), with representation from all age groups. Most of them had been practicing for more than 10 years as gastroenterologists (71.3%) in a hospital (96.2%). (Complete information in Appendix C.)

Regarding the level of knowledge about the different aspects of health centres in the area, most participants reported having access to calprotectin (69.5%), gastrointestinal ultrasound (72.1%) and colonoscopy (80.7%). Less than half of the respondents confirmed that they knew the number of centres in the area (44.8%) or had access to bone density testing (30.3%).

Regarding the general relationship between Gastroenterology and PC in the health area, 43.8% considered it good; 32.7%, average; 3.9%, poor and 15.7, neutral (Fig. 1). Based on the type of relationship, considering multiple choice questions, 19.9% of respondents said they did not have any type of active relationship/intervention in daily practice (without taking into account a research or training context). Thirty-six point four per cent and 63.6% reported having a relationship over the phone or through electronic medical records, respectively. Nine point three per cent and 6.3% confirmed they had some kind of relationship through face-to-face or online meetings, respectively. Five point two percent reported having a relationship with a representative by service. Twelve point two percent of respondents selected other options, such as consultations, e-consultations or email. Finally, regarding the average degree of satisfaction with the active relationship/interaction in daily practice with family doctors, from 0 to 10, the average score was 5.4±2.4.

Most of the respondents (60.7%) indicated not having any type of training activity with PC. The rest reported participating in activities such as workshops (10%), courses (24.7%), conferences or scientific meetings (2%), working groups (5.3%), research projects (2.7%) and/or others (8.7%). In general terms, the perception of the general support received from PC in the case of IBD, from 0 to 10, was 4.4±2.4.

Regarding the diagnosis and management of IBD patients, for 77.0% of respondents the responsibilities, functions and actions of PC and Gastroenterology were not well defined. The majority (75.0%) said they do not have access to resources such as protocols, consensuses, algorithms or the like for diagnosis, referral or agreed management with PC.

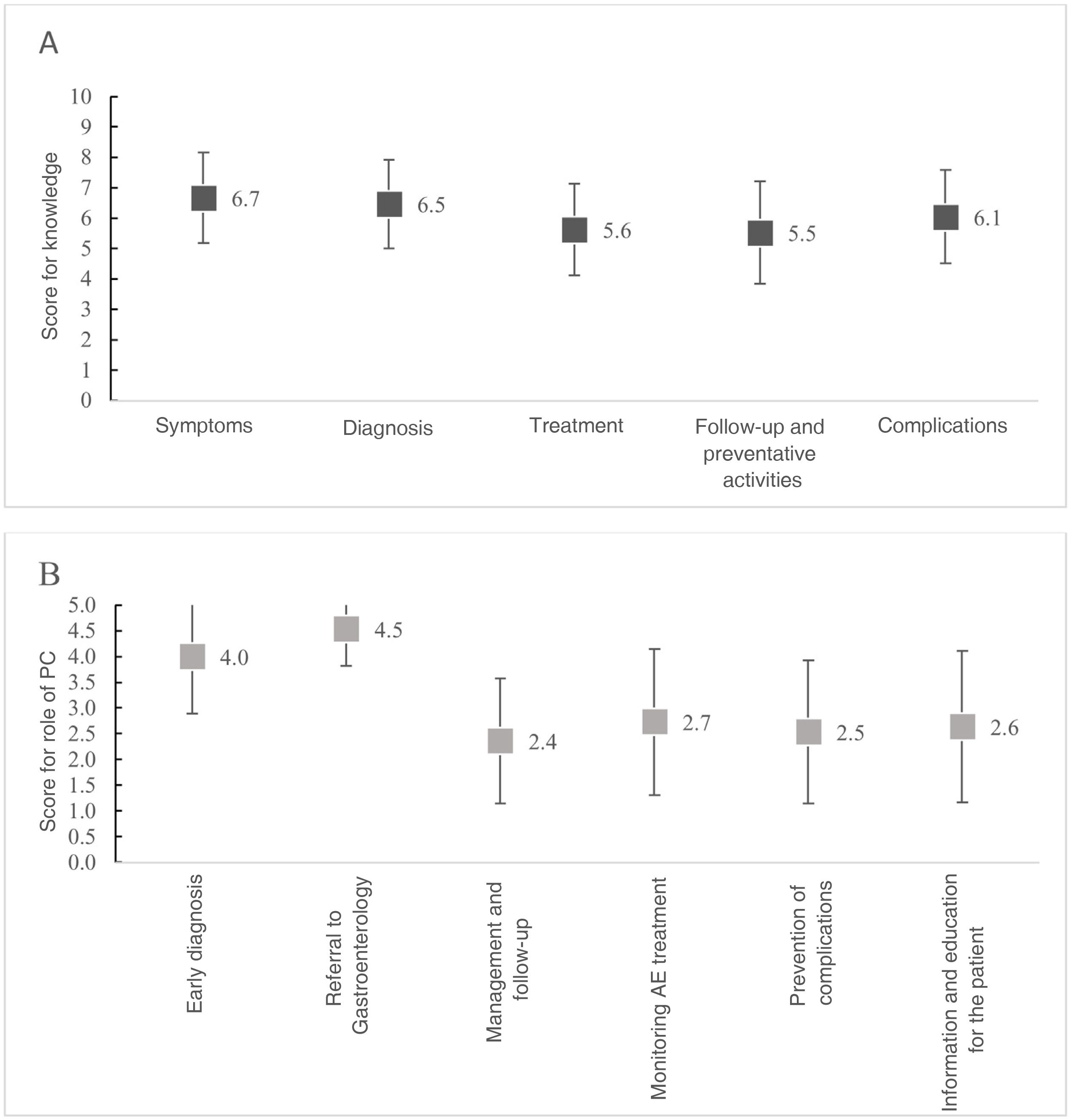

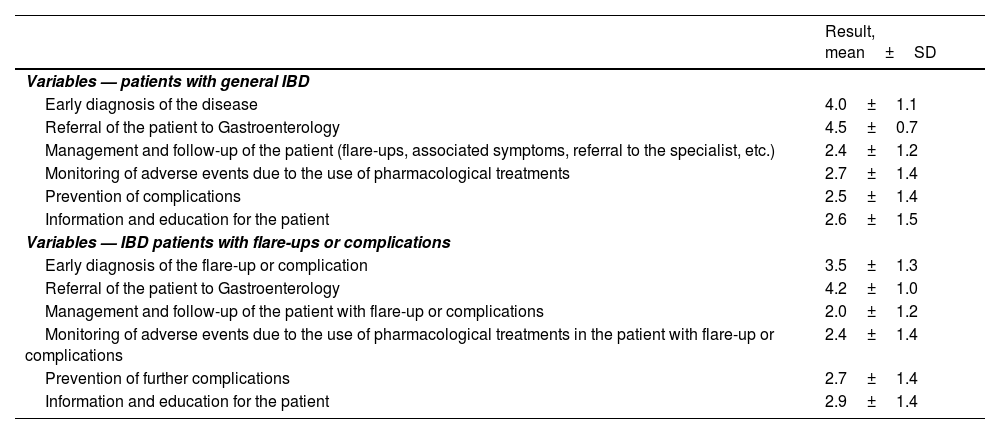

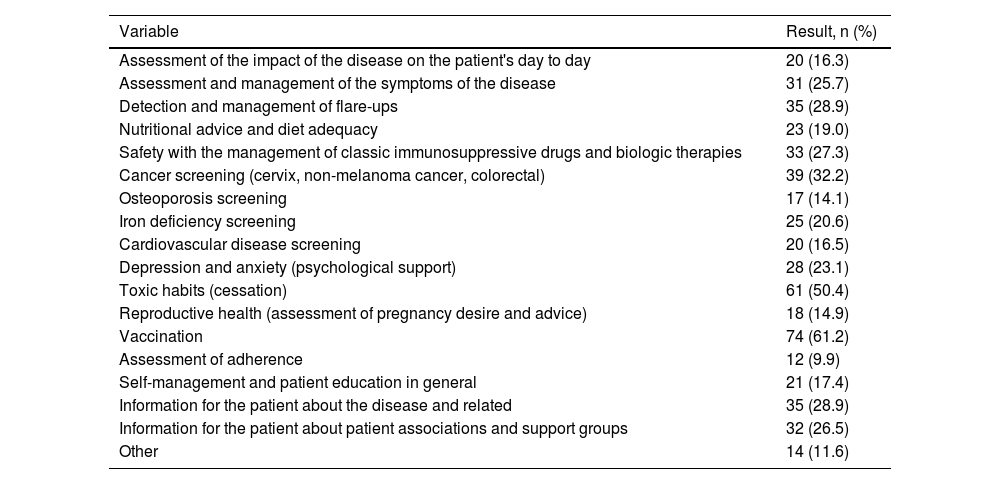

Regarding the importance of the role or function of family doctors, from 0 to 5, respondents rated early diagnosis and patient referral at 4.0±1.1 and 4.5±0.7, respectively. However, in the rest of the functions the scores were less than 3 (Fig. 2). Similarly, scores were similar for IBD patients with flare-ups or complications (Table 1). On the other hand, less than 30% of respondents provided information to their family doctors about the different aspects of managing IBD patients (Table 2). They only claimed to give explicit indications on vaccination (61.2%) and toxic habits (50.4%). In general, gastroenterologists revealed that they discuss these issues with the patient, but not with family doctors.

Score for knowledge of family doctors about the different aspects of IBD compared to the degree of involvement in them. (A) Score from 0 (none) to 10 (a lot) for the level of knowledge about the following aspects based on the opinion of the respondents. (B) Score from 0 (none) to 5 (a lot) for the role and function (and therefore involvement) that PC would have in the following aspects, based on the opinion of the Gastroenterology respondents.

AE: adverse event.

Score from 0 (none) to 5 (a lot) of the role and function (and therefore involvement) that family doctors would have in the following aspects in a patient with IBD in general and in flare-ups or complications.

| Result, mean±SD | |

|---|---|

| Variables — patients with general IBD | |

| Early diagnosis of the disease | 4.0±1.1 |

| Referral of the patient to Gastroenterology | 4.5±0.7 |

| Management and follow-up of the patient (flare-ups, associated symptoms, referral to the specialist, etc.) | 2.4±1.2 |

| Monitoring of adverse events due to the use of pharmacological treatments | 2.7±1.4 |

| Prevention of complications | 2.5±1.4 |

| Information and education for the patient | 2.6±1.5 |

| Variables — IBD patients with flare-ups or complications | |

| Early diagnosis of the flare-up or complication | 3.5±1.3 |

| Referral of the patient to Gastroenterology | 4.2±1.0 |

| Management and follow-up of the patient with flare-up or complications | 2.0±1.2 |

| Monitoring of adverse events due to the use of pharmacological treatments in the patient with flare-up or complications | 2.4±1.4 |

| Prevention of further complications | 2.7±1.4 |

| Information and education for the patient | 2.9±1.4 |

Clear and/or explicit instructions to family doctors on any of the following (multiple choice).

| Variable | Result, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Assessment of the impact of the disease on the patient's day to day | 20 (16.3) |

| Assessment and management of the symptoms of the disease | 31 (25.7) |

| Detection and management of flare-ups | 35 (28.9) |

| Nutritional advice and diet adequacy | 23 (19.0) |

| Safety with the management of classic immunosuppressive drugs and biologic therapies | 33 (27.3) |

| Cancer screening (cervix, non-melanoma cancer, colorectal) | 39 (32.2) |

| Osteoporosis screening | 17 (14.1) |

| Iron deficiency screening | 25 (20.6) |

| Cardiovascular disease screening | 20 (16.5) |

| Depression and anxiety (psychological support) | 28 (23.1) |

| Toxic habits (cessation) | 61 (50.4) |

| Reproductive health (assessment of pregnancy desire and advice) | 18 (14.9) |

| Vaccination | 74 (61.2) |

| Assessment of adherence | 12 (9.9) |

| Self-management and patient education in general | 21 (17.4) |

| Information for the patient about the disease and related | 35 (28.9) |

| Information for the patient about patient associations and support groups | 32 (26.5) |

| Other | 14 (11.6) |

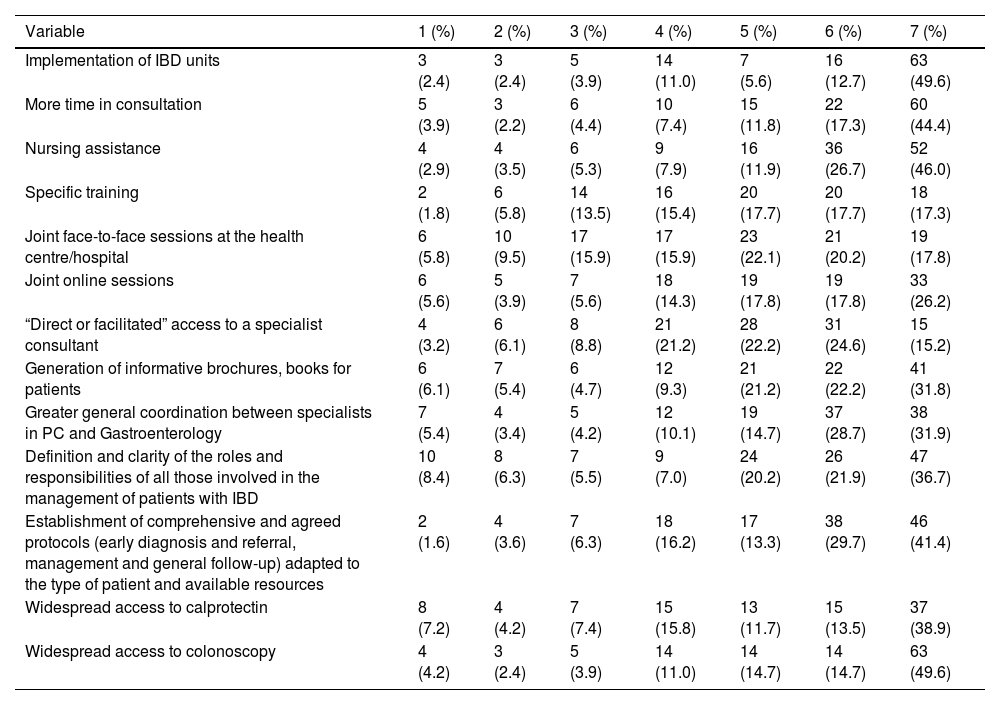

Finally, among the improvements in daily clinical practice for patient management, respondents indicated mainly that the most relevant improvements would be: the implementation of IBD units, nursing assistance and specific training (Table 3).

The 7 improvements considered the most relevant scored by their importance from 1 (of 7, the least important) to 7 (of 7, the most important) for gastroenterologists surveyed (multiple choice).

| Variable | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | 6 (%) | 7 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation of IBD units | 3 (2.4) | 3 (2.4) | 5 (3.9) | 14 (11.0) | 7 (5.6) | 16 (12.7) | 63 (49.6) |

| More time in consultation | 5 (3.9) | 3 (2.2) | 6 (4.4) | 10 (7.4) | 15 (11.8) | 22 (17.3) | 60 (44.4) |

| Nursing assistance | 4 (2.9) | 4 (3.5) | 6 (5.3) | 9 (7.9) | 16 (11.9) | 36 (26.7) | 52 (46.0) |

| Specific training | 2 (1.8) | 6 (5.8) | 14 (13.5) | 16 (15.4) | 20 (17.7) | 20 (17.7) | 18 (17.3) |

| Joint face-to-face sessions at the health centre/hospital | 6 (5.8) | 10 (9.5) | 17 (15.9) | 17 (15.9) | 23 (22.1) | 21 (20.2) | 19 (17.8) |

| Joint online sessions | 6 (5.6) | 5 (3.9) | 7 (5.6) | 18 (14.3) | 19 (17.8) | 19 (17.8) | 33 (26.2) |

| “Direct or facilitated” access to a specialist consultant | 4 (3.2) | 6 (6.1) | 8 (8.8) | 21 (21.2) | 28 (22.2) | 31 (24.6) | 15 (15.2) |

| Generation of informative brochures, books for patients | 6 (6.1) | 7 (5.4) | 6 (4.7) | 12 (9.3) | 21 (21.2) | 22 (22.2) | 41 (31.8) |

| Greater general coordination between specialists in PC and Gastroenterology | 7 (5.4) | 4 (3.4) | 5 (4.2) | 12 (10.1) | 19 (14.7) | 37 (28.7) | 38 (31.9) |

| Definition and clarity of the roles and responsibilities of all those involved in the management of patients with IBD | 10 (8.4) | 8 (6.3) | 7 (5.5) | 9 (7.0) | 24 (20.2) | 26 (21.9) | 47 (36.7) |

| Establishment of comprehensive and agreed protocols (early diagnosis and referral, management and general follow-up) adapted to the type of patient and available resources | 2 (1.6) | 4 (3.6) | 7 (6.3) | 18 (16.2) | 17 (13.3) | 38 (29.7) | 46 (41.4) |

| Widespread access to calprotectin | 8 (7.2) | 4 (4.2) | 7 (7.4) | 15 (15.8) | 13 (11.7) | 15 (13.5) | 37 (38.9) |

| Widespread access to colonoscopy | 4 (4.2) | 3 (2.4) | 5 (3.9) | 14 (11.0) | 14 (14.7) | 14 (14.7) | 63 (49.6) |

Most of the respondents were women (63.8%), with representation from all age groups, although with greater prevalence in the older age groups. Most of them had been practising for more than 10 years in the area (65.8%) in a health centre (66.7%). Thirty-one percent of respondents resided in Cantabria. The rest of the autonomous communities of residence of PC specialists are shown in the Supplementary material (Appendix D).

Regarding the level of knowledge about IBD, respondents rated an average score of 6.7±1.5 for symptoms, 6.5±1.5 for diagnosis, 5.6±1.5 for treatment, 5.5±1.5 for follow-up and preventive activities and 6.1±1.5 for its complications (Fig. 2).

Regarding the general relationship between Gastroenterology and PC in the health area, 34.3% considered it good; 30.4%, average; 11.3%, poor and 22.6, neutral (Fig. 1). Forty-eight percent stated that they did not have any type of active relationship/intervention in daily practice with the IBD unit of the Gastroenterology services (without taking into account a research or training context). Twenty-nine point four percent and 13.3% reported having a relationship over the phone or through electronic medical records, respectively. Three point nine percent and 2.5% confirmed that they had some kind of relationship through face-to-face meetings, or online meetings, respectively. Five point nine percent reported having a relationship with a representative by service. Fourteen point two percent selected other options, such as consultations, e-consultations, multidisciplinary approach, easy access in small hospitals, etc. Finally, regarding the average degree of satisfaction with the active relationship/interaction in daily practice with Gastroenterology, from 0 to 10, the average score was 5.0±3.1.

Most of the respondents (61.7%) indicated not having any type of active training/interaction with Gastroenterology outside the sphere of daily practice. The rest reported participating in activities such as workshops (9.5%), courses (22.4%), conferences or scientific meetings (14.4%), working groups (9.9%), research projects (3.5%) or others (2.5%). In general terms, the perception of the general support received from Gastroenterology in the case of IBD, from 0 to 10, was 4.3±2.7.

Regarding the diagnosis and management of IBD patients, for 76.2% of respondents the responsibilities, functions and actions of PC and Gastroenterology were not well defined. Most reported having access to the patient’s medical history (91.2%), colonoscopy (66.8%), gastrointestinal ultrasound (56.5%) and calprotectin (63.7%). However, only 30.6% have a protocol for the diagnosis, referral or management of the IBD patient, and 22.3% have clear indications or explicit guidelines by the gastroenterologist. On the other hand, the average score, from 0 to 10, regarding the ease of referring patients with suspected or already diagnosed IBD to the gastroenterologist, was 6.1±2.7 and 5.7±2.7, respectively.

Among the actions carried out in the diagnosis and management of IBD patients, most reported participating in the symptoms (86.4%), the diagnosis (65.5%), in the follow-up and in preventive activities (71.3%). In contrast, in the treatment and in the complications the participation dropped to 35.6% in both cases. Respondents rated safety in early diagnosis at 5.8±1.4, management and follow-up at 5.8±1.2, referral to Gastroenterology at 6.0±1.4, monitoring of adverse events derived from treatment at 5.6±1.2, prevention of complications at 5.5±1.5, and patient information and education at 5.9±1.4.

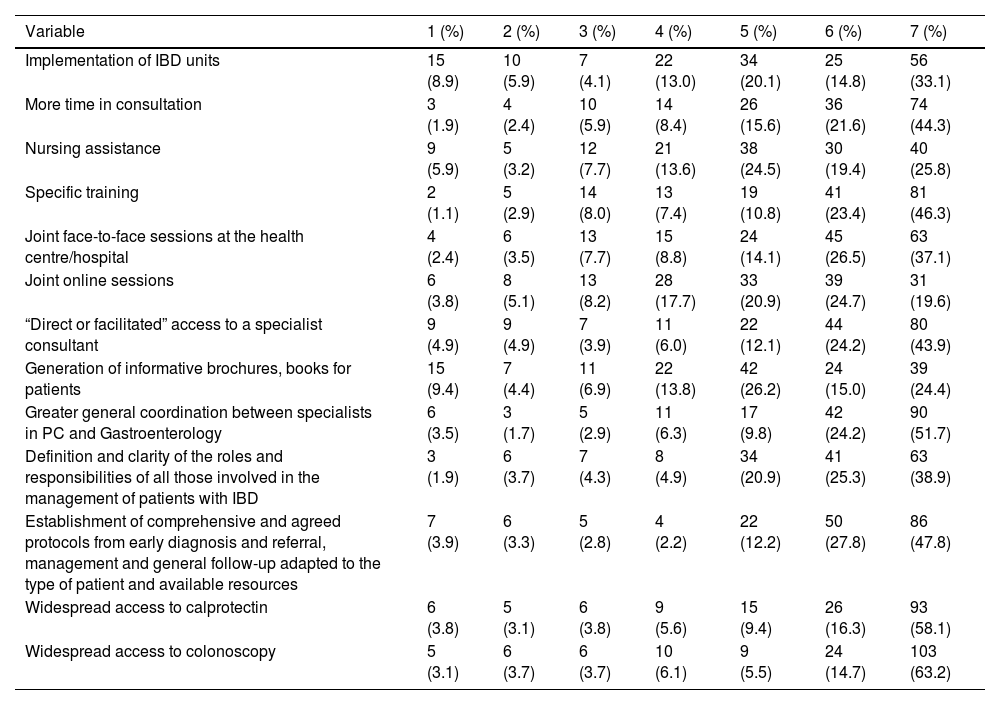

Finally, within the improvements in daily clinical practice for the management of IBD patients, respondents said that the most relevant improvements would be: greater overall coordination between PC and Gastroenterology specialists, the establishment of comprehensive and agreed protocols from early diagnosis and referral to general follow-up and management adapted to the type of patient and available resources, and widespread access to colonoscopy (Table 4).

The 7 improvements considered the most relevant scored by their importance from 1 (of 7, the least important) to 7 (of 7, the most important) for family doctors surveyed (multiple choice).

| Variable | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | 6 (%) | 7 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation of IBD units | 15 (8.9) | 10 (5.9) | 7 (4.1) | 22 (13.0) | 34 (20.1) | 25 (14.8) | 56 (33.1) |

| More time in consultation | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.4) | 10 (5.9) | 14 (8.4) | 26 (15.6) | 36 (21.6) | 74 (44.3) |

| Nursing assistance | 9 (5.9) | 5 (3.2) | 12 (7.7) | 21 (13.6) | 38 (24.5) | 30 (19.4) | 40 (25.8) |

| Specific training | 2 (1.1) | 5 (2.9) | 14 (8.0) | 13 (7.4) | 19 (10.8) | 41 (23.4) | 81 (46.3) |

| Joint face-to-face sessions at the health centre/hospital | 4 (2.4) | 6 (3.5) | 13 (7.7) | 15 (8.8) | 24 (14.1) | 45 (26.5) | 63 (37.1) |

| Joint online sessions | 6 (3.8) | 8 (5.1) | 13 (8.2) | 28 (17.7) | 33 (20.9) | 39 (24.7) | 31 (19.6) |

| “Direct or facilitated” access to a specialist consultant | 9 (4.9) | 9 (4.9) | 7 (3.9) | 11 (6.0) | 22 (12.1) | 44 (24.2) | 80 (43.9) |

| Generation of informative brochures, books for patients | 15 (9.4) | 7 (4.4) | 11 (6.9) | 22 (13.8) | 42 (26.2) | 24 (15.0) | 39 (24.4) |

| Greater general coordination between specialists in PC and Gastroenterology | 6 (3.5) | 3 (1.7) | 5 (2.9) | 11 (6.3) | 17 (9.8) | 42 (24.2) | 90 (51.7) |

| Definition and clarity of the roles and responsibilities of all those involved in the management of patients with IBD | 3 (1.9) | 6 (3.7) | 7 (4.3) | 8 (4.9) | 34 (20.9) | 41 (25.3) | 63 (38.9) |

| Establishment of comprehensive and agreed protocols from early diagnosis and referral, management and general follow-up adapted to the type of patient and available resources | 7 (3.9) | 6 (3.3) | 5 (2.8) | 4 (2.2) | 22 (12.2) | 50 (27.8) | 86 (47.8) |

| Widespread access to calprotectin | 6 (3.8) | 5 (3.1) | 6 (3.8) | 9 (5.6) | 15 (9.4) | 26 (16.3) | 93 (58.1) |

| Widespread access to colonoscopy | 5 (3.1) | 6 (3.7) | 6 (3.7) | 10 (6.1) | 9 (5.5) | 24 (14.7) | 103 (63.2) |

IBD is a worldwide disease and represents a major health problem. It has a higher incidence rate in developed or westernised countries.4 In addition, in these countries growth is estimated at 3% every five years.3 IBD has a significant impact on the life of the patient, due to its chronicity and its onset generally at early ages, since 50% of patients are between 20 and 39 years old, a fundamental stage in the professional and personal domains. Therefore, poor control of the disease can have negative effects on the physical and psychosocial well-being of the patient.8,9,16–18

PC plays a very important role in the detection of IBD, as it is the first point of contact for the patient after the onset of symptoms.13 On the other hand, given the complexity of the disease, diagnosis and follow-up are mainly performed by specialists from the IBD units of Gastroenterology. Specialised and multidisciplinary IBD units have been established in most hospitals in Spain. These units are run by teams that handle the most complex cases19 in which GETECCU has worked with training and promotion. They are global pioneers with the Certificación de Unidades de Atención Integral de EII [IBD Comprehensive Care Unit Certification programme] (CUE).20 Although this model has demonstrated high efficiency in patient management and has allowed for the reduction of hospital stays, in our study, only 5.7% of PC respondents say they have access to IBD units. In addition, it has been shown that, within the multidisciplinary team, specialised nursing in IBD and PC have a complementary role during follow-up.13,19,21 The data from this survey show the need, at both levels of care, for greater general coordination between specialists in PC and Gastroenterology, the implementation of IBD units, their dissemination in PC and the relevance of skilled nursing.

In line with the areas for improvement, the most widespread model, and that recommended by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO), is one in which PC participates in coordination with specialised units, following the guidelines’ recommendations, especially in the implementation of preventive measures in IBD patients that boost their “self-care”.19 However, 75.0% and 69.4% of gastroenterologists and family physicians surveyed, respectively, claim that they do not have comprehensive and agreed protocols (early diagnosis and referral, management and general follow-up) adapted to the type of patient and available resources.

Despite the availability of a number of carefully developed clinical practice guidelines, such as guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology,22 the American College of Gastroenterology,23 the World Gastroenterology Organisation,24 European guidelines (ECCO)25 and the GETECCU positioning documents,26 the two specialties agree on the lack of specified actions, roles and responsibilities, as occurs, for example, in the case of faecal calprotectin. In addition, while existing guidelines are useful, they are not designed for the PC environment, making them difficult to apply. A large proportion of IBD care occurs in the outpatient setting and, consequently, adequate knowledge of the disease and its basic management by family physicians is important to improve outcomes.27 In our environment, only 22.3% of the family doctors surveyed indicate having access to clear and/or explicit indications/guidelines/suggestions by the gastroenterologist. On the other hand, most gastroenterologists admit to only providing PC with clear indications about toxic habits (50.4%) and vaccination (61.2%).

Coordination between specialists in PC and Gastroenterology is essential to offer good quality care. However, there are currently no studies that have previously evaluated this relationship in IBD in Spain. Only in 2010, in the study carried out by Gené et al.15 in Catalonia was it concluded that the degree of interaction between the two units was insufficient. The evidence reveals that the quality of care by the gastroenterologist and the family doctor improves when the degree of personal interaction between the specialties is high. This work was carried out in full compliance with the principles established in the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki, regarding medical research in human beings and in accordance with the applicable regulations on Good Clinical Practices. Therefore, it is necessary to implement improvements that allow for communication, resolving issues and offering quick solutions, avoiding errors and additional costs.28 However, the survey shows that although most gastroenterologists surveyed believe that PC plays a significant role in early diagnosis and referral, only 43.8% and 34.3% of gastroenterologists and family doctors, respectively, consider it to be a good relationship. These data justify that the perception of support between the two specialties does not exceed 4.5 in either survey. In addition, more than 60% of the total respondents say they do not have any active relationship or interaction outside the scope of clinical practice.

After the evaluation of the results of the surveys, GETECCU and SEMERGEN propose the following collaborative improvement actions (some focused on clinical practice, others educational, and others related to the dissemination and use of existing opportunities or resources) which should be adapted to the peculiarities of each locality: 1) generation of agreed protocols between family doctors and gastroenterologists (for diagnosis, referral and monitoring); 2) local level participation in joint sessions; and 3) other proposals: optimisation of existing GETECCU resources, such as the G-Educainflamatoria portal (educainflamatoria.com), and improvements in communication, such as the notification of accreditation by IBD units to health centres dependent on them.

Lastly, this study has some limitations. As it was a study carried out through an online survey, a selection bias is inevitable. Thus, the opinion of the respondents may not match the usual practice of other specialists. Further, a bias could be considered in the fact that the doctors who responded to the survey would be the most interested in establishing partnerships between the two units for the management of patients with IBD, while those who did not respond would be those who would not be as interested in the issue or who would consider such partnerships unnecessary. It is also not possible to determine whether those who did not respond to the survey have the same views as those who did. In terms of strengths, the respondents are active health professionals from the specialties of interest, from different autonomous communities and hospitals, whose opinions are based on their routine clinical experience. In addition, despite the diversity of affiliations, there is unity in their perspectives, so this data could be extrapolated to other centres.

ConclusionCoordination between the different levels of care and a multidisciplinary approach are essential to provide quality care. This requires a close relationship and greater coordination between PC and Gastroenterology, the implementation of IBD units, nursing collaboration and the development of protocols. In addition, communication between the units should be smooth, fast and effective for early referral in case of suspected IBD.29 Finally, SEMERGEN and GETECCU present different collaborative improvement actions.

Ethical considerationsThis work was carried out in full compliance with the principles established in the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki, regarding medical research in human beings, and in accordance with the applicable regulations on Good Clinical Practices.

FundingThis work has received funding from Laboratorios Ferring S.A.U.

Author’s contributionAll authors participated in the conceptualisation of the project, the design of the surveys, the evaluation of the results, the drafting and the critical review of the manuscript. All authors have given their approval for the final version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this study.

The authors would like to thank the Instituto de Salud Musculoesquelética [Institute of Musculoskeletal Health] (Inmusc) for its support in conducting and distributing the survey and Meisys (Madrid, Spain) for its support with the drafting of the manuscript.