Colonoscopy is the gold standard procedure for detecting neoplastic lesions of the colon and its efficiency is closely linked to the quality of the procedure. Adequate bowel preparation is a crucial factor in achieving the recommended quality indicators, but poor preparation has been reported in up to 30% of outpatients referred for colonoscopy. Consequently, over recent years, a number of studies have developed strategies to optimise bowel cleansing by improving adherence and tolerance to and the efficacy of the bowel preparation. Moreover, the identification of risk factors for inadequate bowel cleansing has led to tailored bowel preparation strategies being designed, with promising results. We aimed to review studies that assessed risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation and strategies to optimise bowel cleansing in patients at high risk of having poor preparation.

La colonoscopia es el patrón oro para el diagnóstico de lesiones epiteliales colorrectales y su eficiencia está íntimamente relacionada con la calidad de la exploración. Lograr una adecuada limpieza colónica es un factor fundamental para alcanzar los estándares de calidad recomendados. Actualmente, hasta el 30% de los pacientes a los que se realiza una colonoscopia ambulatoria presentan una calidad deficiente. Por ello, en los últimos años numerosos estudios han diseñado estrategias para optimizar la limpieza colónica mejorando la adherencia y la tolerancia de la solución de limpieza colónica o la eficacia de esta. La identificación de factores predictores de una limpieza colónica inadecuada ha propiciado el desarrollo de estrategias de preparación individualizadas con resultados prometedores. En este artículo se revisan los estudios que evaluaron los factores asociados a una limpieza colónica deficiente, así como las estrategias diseñadas para optimizar la limpieza colónica en pacientes con elevada probabilidad de una limpieza colónica inadecuada.

Colonoscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of colorectal epithelial lesions, and it has been shown to reduce incidence and mortality rates in colorectal cancer screening programmes.1 The efficiency of colonoscopy depends on multiple indicators, such as the caecal intubation rate and the adenoma detection rate (ADR), but these factors directly depend on the degree of bowel cleanliness. Poor bowel preparation negatively affects these indicators and is associated with technical difficulties, a higher risk of complications, an increase in costs and shortening of the endoscopic surveillance intervals.2,3

Despite the importance of bowel cleanliness, the published rate for colonoscopies with poor preparation in endoscopy units is as high as 30%.4 As a consequence, researchers have been examining the risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation and designing strategies to improve bowel cleanliness, such as: (1) encouraging better patient adherence to the preparation instructions; (2) modifying the dietary recommendations in the days prior to the colonoscopy; (3) modifying the type or form of prescription of the purgative agent; and (4) developing rescue devices.5–7

In this review, we analyse the current recommendations on bowel preparation, the factors associated with poor bowel cleansing and interventions to improve the quality of cleanliness in groups at risk of inadequate cleansing.

Assessment of bowel preparationBowel cleanliness should be assessed after making the maximum effort to flush and suction all remaining faecal debris. Bowel preparation is considered adequate if the colonoscopist is able to identify colorectal lesions larger than 5mm, determined to be clinically significant. Therefore, if the indication for the colonoscopy is screening for colorectal cancer or post-polypectomy surveillance and the quality of bowel preparation does not allow these lesions to be identified, the procedure will have to be repeated within a year.2

Three bowel preparation assessment scales, the Boston (BBPS), Ottawa and Aronchick preparation scales, have been widely studied and have demonstrated suitable validity and reliability.8 A systematic review concluded that the BBPS provides the greatest intra- and interobserver agreement and that it has the best correlation with ADR,9 and it is therefore recommended in clinical practice.8 There is an on-line training programme available for the BBPS (www.cori.org/bbps).9 Based on the application of these scales, patients having colonoscopies with intermediate or high-quality cleansing should continue with the endoscopic surveillance intervals established in the clinical practice guidelines, while patients with poor quality bowel preparation will need to have a repeat procedure at an earlier date.10 According to the BBPS, an overall score ≥6 with a score of ≥2 per colon segment means bowel preparation quality is adequate and the recommended endoscopic surveillance intervals can be followed.11 The societies recommend that no more than 10–15% per year of colonoscopies performed in an endoscopy unit should have inadequate bowel preparation8, recommending an audit if this rate is exceeded.12 However, the figures reported for colonoscopies with inadequate cleansing range from 9% to 30%.4

Preparation prior to colonoscopyColonoscopy preparation should be anterograde, taking a bowel cleansing solution to which some adjuvant may be added, and a specific diet.12–14

Dietary aspectsThe European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) recommend a low-residue diet the day before the colonoscopy, while the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer gives the same level of evidence to that diet and a liquid diet.12–14 Liquid diet refers to liquid products which do not produce a high osmotic load in the intestinal lumen, with carbohydrates, little protein and salt. A low-residue diet includes low-fibre foods and any food that increases the volume of the faecal mass. A recent meta-analysis showed that patients who received a low-fibre diet tolerated it better and were more disposed to repeat it, with no differences in the quality of bowel cleanliness or adverse effects.5 It is therefore suggested that the low-residue diet should be the one of choice.

Although a low-residue diet is recommended from one to three days before the colonoscopy depending on the characteristics of each patient, the most common regimen in unselected population is to make the dietary modifications the day before the examination. In fact, a recent prospective study showed that only the dietary intake the day before the colonoscopy, and not that of the previous two or three days, correlated with the bowel cleansing quality.15

Type of bowel cleansing solutionsBowel cleansing solutions can be classified according to the mechanism of action into osmotic agents or stimulating agents. The osmotic agents act by drawing water into the colon, like polyethylene glycol (PEG), or by producing an increase in intraluminal water by drawing it from the intravascular space, like the hyperosmolar salts, sodium phosphate and magnesium citrate/oxide. Stimulating agents, such as sodium picosulfate and bisacodyl, cause contraction of the intestinal wall, speeding up the evacuation of bowel contents.16

The solutions most commonly used in the past were based on high-volume PEG (3–4l), but 5–15% of patients did not complete the preparation due to the high volume and/or unpleasant taste. As a consequence, low-volume preparations have been developed based on the combination of PEG (2 or 1l) and an adjuvant such as ascorbic acid (PEG+Asc)14,17 or preparations based on the combination of sodium picosulfate and magnesium citrate/oxide. Several meta-analyses carried out in unselected populations have shown that there are no differences in the quality of bowel cleansing between high-volume PEG-based and low-volume preparations.7,18 However, the use of low-volume preparations has been associated with better acceptance, better adherence, better tolerance and a lower rate of adverse effects.18,19 Similar results were recently published from two randomised clinical trials for preparations based on 1l PEG+Asc, where the quality of bowel cleansing was not inferior or was even superior to other low-volume preparations (PEG+Asc or sodium picosulfate with magnesium citrate). Moreover, despite the fact that 1l of PEG+Asc is associated with a somewhat higher rate of nausea/vomiting, it has a good safety profile.20,21

Bowel cleansing solutions administration methodDose splittingSplitting the administration of the bowel preparation solution, with part of the preparation taken on the same day as the colonoscopy, is the most accepted method for colonoscopies taking place in the mornings. This method should not be an impediment to administering sedation, as no significant differences in residual gastric volume have been found in patients who take the preparation in split doses compared to those who take it the day before the procedure, besides the fact that they are able to maintain the 2h of fasting recommended by the American Society of Anesthesiologists.22,23 Greater efficacy has been demonstrated using this strategy compared with taking all the preparation the day before the examination.24 The benefit of this regimen is attributed to the shorter time between completion of the preparation and the start of the colonoscopy, with the maximum benefit being obtained from 3 to 5h after the last intake of the preparation.24 In addition to improving patient adherence, this regimen is associated with greater detection of colorectal cancer lesions.25 For afternoon colonoscopies, it has traditionally been recommended to administer the preparation on the same day as the procedure.13 However, two recent meta-analyses of patients who had their colonoscopies in the morning or the afternoon showed that there were no differences in the quality of bowel cleansing or in the lesion detection rate between patients who did the preparation on the same day as the procedure or patients who took it in split doses.26,27 Therefore, the choice of dosage type in these cases should be based on the patient's preferences.

In patients who are unable to swallow the preparation, a nasogastric tube can be used.14

Risk factors for poor bowel preparationA number of studies have analysed predictive factors for poor bowel preparation. However, this was not the primary endpoint in most cases and their results lose value due to the small sample size, the inclusion of a limited number of variables and the lack of a validated preparation scale.28–32

The factors associated with poor bowel preparation can be classified as patient-dependent or preparation-related. The patient-dependent factors include epidemiological and socioeconomic factors such as older age (>60),31 being male,31 low educational level,32 being single and motivation (patients with previous endoscopic polypectomy or family history of colorectal cancer)31. Moreover, up to 20% of patients with poor bowel preparation do not adhere to the instructions.31 Also important are factors associated with the inhibition of intestinal motility, such as chronic constipation,33–35 abdominal or pelvic surgery34 (especially patients with left colectomy),36 the use of calcium antagonists,34 tricyclic antidepressants33,34 and/or opioids,33 comorbidity,31,33,34 a high body mass index 28and hospitalisation.31,33

The preparation-related factors include inappropriate indication, more than 5h from completion of the preparation to the start of colonoscopy32,37 and a previous history of poor bowel preparation, which is considered as the most relevant predictive factor.14

A recent meta-analysis showed that sociodemographic characteristics (gender and age) are predictors of bowel cleanliness with a marginal effect, while comorbidities such as diabetes, stroke or dementia and treatments such as opioids and tricyclic antidepressants are more powerful predictors.38 Three recent studies found that an accumulation of different factors increases the likelihood of poor preparation.28,33,34 In a prospective, multicentre study, Hassan et al.28 assessed 2811 consecutive colonoscopies, where 33% of the patients had poor bowel preparation. The independent predictors of bowel cleanliness were: being male, high body mass index, older age, previous colorectal surgery, liver cirrhosis, Parkinson's disease, diabetes and a negative faecal occult blood test. However, the predictive model designed with these variables had a low discrimination capacity (area under the curve [AUC]: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.62–0.66). The Hassan et al. study has significant methodology limitations, such as the lack of standardisation in the type of bowel preparation solution used, the lack of dose splitting in most patients and the use of a non-validated scale to rate bowel cleanliness. In another prospective, multicentre study with 1996 patients who received high- or low-volume PEG in split doses, Dik et al.33 found that 12.9% of the patients had inadequate bowel preparation according to the BBPS scale. The predictive factors associated with this condition included in a predictive model were: a score≥3 in the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System; use of tricyclic antidepressants and opioids; diabetes; chronic constipation; history of abdominal or pelvic surgery; previous inadequate bowel preparation; and hospitalisation. However, the preparation protocols differed from one centre to another. They also included patients with a history of inadequate bowel preparation, which is a significant factor as, once lack of adherence is excluded, more intensive preparations should be recommended to these patients.34 To overcome these limitations, Gimeno-García et al.34 analysed predictive factors of inadequate bowel preparation in 1057 outpatients prepared on the same day as the examination with low- and high-volume bowel preparation solutions. Cleanliness was assessed with the BBPS scale. Comorbidity, taking antidepressants, chronic constipation, and pelvic or abdominal surgery were independent predictors of poor bowel preparation.

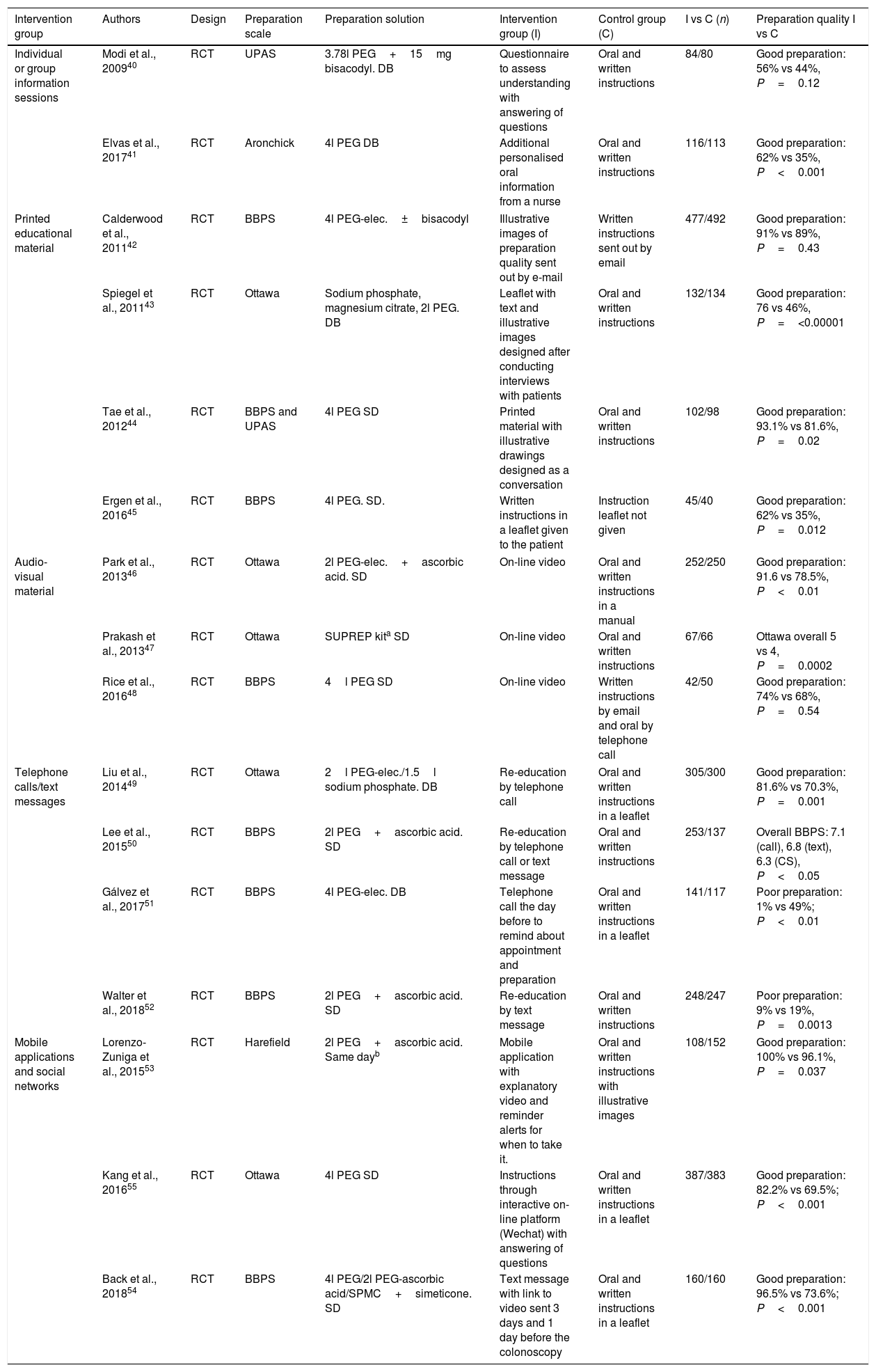

Interventions aimed at optimising the quality of bowel preparationEducational strategiesGiven the importance of achieving adequate quality of preparation, it is vital that the patient understands the instructions received. Although the endoscopy societies recommend that patients receive oral and written instructions in plain language, they do not specify the precise form in which or the specific time this information should be provided.13,14 Moreover, these instructions do not seem to be effective enough to obtain optimal rates of adequate bowel preparation.6 Several studies have assessed the effectiveness of different educational strategies in improving comprehension and the degree of compliance with and adherence to the recommendations about bowel preparation. Two meta-analyses6,39 which compared the quality of bowel cleanliness using different educational strategies with using standard instructions given orally and in writing demonstrated a higher rate of adequate bowel preparation in patients who received some additional educational strategy (88.5% vs 78.4%), and found that they were more disposed to repeat the preparation (90.5% vs 83.1%). There were no differences in the ADR. Despite the above results, the educational strategies included a heterogeneous group of interventions and the effects can be quite diverse, so there is no consensus on which is the most effective. The results are discussed below according to the type of strategy used.

- 1.

Personalised or group information sessions. These sessions are given by trained healthcare personnel and the patient receives instructions on dietary aspects, the type and method of administration of the purgative preparation and precautions to be taken with the treatment at home. The few existing published studies 40,41have produced inconsistent results (Table 1).

Table 1.Characteristics of published studies on educational strategies aimed at improving the quality of bowel preparation.

Intervention group Authors Design Preparation scale Preparation solution Intervention group (I) Control group (C) I vs C (n) Preparation quality I vs C Individual or group information sessions Modi et al., 200940 RCT UPAS 3.78l PEG+15mg bisacodyl. DB Questionnaire to assess understanding with answering of questions Oral and written instructions 84/80 Good preparation: 56% vs 44%, P=0.12 Elvas et al., 201741 RCT Aronchick 4l PEG DB Additional personalised oral information from a nurse Oral and written instructions 116/113 Good preparation: 62% vs 35%, P<0.001 Printed educational material Calderwood et al., 201142 RCT BBPS 4l PEG-elec.±bisacodyl Illustrative images of preparation quality sent out by e-mail Written instructions sent out by email 477/492 Good preparation: 91% vs 89%, P=0.43 Spiegel et al., 201143 RCT Ottawa Sodium phosphate, magnesium citrate, 2l PEG. DB Leaflet with text and illustrative images designed after conducting interviews with patients Oral and written instructions 132/134 Good preparation: 76 vs 46%, P=<0.00001 Tae et al., 201244 RCT BBPS and UPAS 4l PEG SD Printed material with illustrative drawings designed as a conversation Oral and written instructions 102/98 Good preparation: 93.1% vs 81.6%, P=0.02 Ergen et al., 201645 RCT BBPS 4l PEG. SD. Written instructions in a leaflet given to the patient Instruction leaflet not given 45/40 Good preparation: 62% vs 35%, P=0.012 Audio-visual material Park et al., 201346 RCT Ottawa 2l PEG-elec.+ascorbic acid. SD On-line video Oral and written instructions in a manual 252/250 Good preparation: 91.6 vs 78.5%, P<0.01 Prakash et al., 201347 RCT Ottawa SUPREP kita SD On-line video Oral and written instructions 67/66 Ottawa overall 5 vs 4, P=0.0002 Rice et al., 201648 RCT BBPS 4l PEG SD On-line video Written instructions by email and oral by telephone call 42/50 Good preparation: 74% vs 68%, P=0.54 Telephone calls/text messages Liu et al., 201449 RCT Ottawa 2l PEG-elec./1.5l sodium phosphate. DB Re-education by telephone call Oral and written instructions in a leaflet 305/300 Good preparation: 81.6% vs 70.3%, P=0.001 Lee et al., 201550 RCT BBPS 2l PEG+ascorbic acid. SD Re-education by telephone call or text message Oral and written instructions 253/137 Overall BBPS: 7.1 (call), 6.8 (text), 6.3 (CS), P<0.05 Gálvez et al., 201751 RCT BBPS 4l PEG-elec. DB Telephone call the day before to remind about appointment and preparation Oral and written instructions in a leaflet 141/117 Poor preparation: 1% vs 49%; P<0.01 Walter et al., 201852 RCT BBPS 2l PEG+ascorbic acid. SD Re-education by text message Oral and written instructions 248/247 Poor preparation: 9% vs 19%, P=0.0013 Mobile applications and social networks Lorenzo-Zuniga et al., 201553 RCT Harefield 2l PEG+ascorbic acid. Same dayb Mobile application with explanatory video and reminder alerts for when to take it. Oral and written instructions with illustrative images 108/152 Good preparation: 100% vs 96.1%, P=0.037 Kang et al., 201655 RCT Ottawa 4l PEG SD Instructions through interactive on-line platform (Wechat) with answering of questions Oral and written instructions in a leaflet 387/383 Good preparation: 82.2% vs 69.5%; P<0.001 Back et al., 201854 RCT BBPS 4l PEG/2l PEG-ascorbic acid/SPMC+simeticone. SD Text message with link to video sent 3 days and 1 day before the colonoscopy Oral and written instructions in a leaflet 160/160 Good preparation: 96.5% vs 73.6%; P<0.001 BBPS, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale; CS, control strategy; DB, taking the prep the day before the colonoscopy; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IS, intervention strategy; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PEG-elec., polyethylene glycol with electrolytes; RCT, randomised clinical trial; SD, taking the bowel prep in split doses; UPAS, Universal Preparation Assessment Scale.

Colonoscopies were performed on an outpatient basis in the majority of the studies, except two which included only admitted patients.45 The indication for colonoscopy was mainly screening40,42,44,46,48,51,54,55, diagnosis43,49,51,54,55 or endoscopic surveillance43,48,49,55; to a lesser extent, mainly any indication52, any except IBD45,47, not specified53 or polypectomy41. The primary endpoint was the assessment of bowel preparation quality in all of the studies, except Gálvez et al.51, whose primary endpoint also included evaluation of other endoscopic quality indicators.

- 2.

Printed educational material. Understanding is enhanced by the use of leaflets or pamphlets that combine text with images or illustrative drawings on good or bad bowel preparation, lesions detected according to bowel cleanliness and foods allowed or forbidden. The distribution of such material had a positive effect on the quality of cleansing in three of the four randomised studies in which this strategy was assessed (Table 1).42–45

- 3.

Audio-visual material. Educational videos can facilitate understanding through the use of simple words, illustrations and video clips. Three randomised clinical trials compared this strategy with usual practice and two of them found better quality bowel preparation in the intervention group46–48 (Table 1).

- 4.

Telephone calls or text messages. Phone calls or texts can be used to send messages stressing the importance of the bowel preparation and explaining about the diet and how to take the purgative preparation, while questions can be answered and a reminder given about the appointment. Four randomised prospective studies49–52 demonstrated better quality bowel preparation in patients assigned to the intervention group (Table 1).

- 5.

Mobile applications and social networks. Mobile telephones and social networks have become an important source of medical information. Two randomised clinical trials assessed53,54 the quality of bowel cleanliness in patients who used a smartphone application that gives detailed colonoscopy preparation information by providing explanatory images and/or videos in comparison to the utility of receiving oral and written instructions, while another study analysed the effect of an application based on an interactive platform.55 In all the studies, the quality of the bowel preparation was higher in the intervention group (Table 1).

Despite these promising results, their accessibility and which of these strategies is more cost-effective has still to be determined.

Mucolytics, prokinetics and stimulantsAdjuvants such as stimulant, prokinetic and antiflatulence agents have been assessed to improve the quality of bowel preparation and the degree of patient adherence to the preparation.17 The ASGE does not recommend routine use and the ESGE makes no specific recommendation regarding the prescribing of adjuvants, although they do suggest the addition of simeticone to improve visualisation of the intestinal mucosa, because of its capacity to reduce bubbles.13,14 A recent multicentre clinical trial in which 289 patients were randomised to receive 2l of PEG with simeticone versus 2l of PEG alone found a higher proportion of adequate bowel cleanliness in the simeticone group (88.2% vs 76.6%, p<0.01), with no differences in safety and compliance.56

Combining PEG with other osmotic agents such as sodium phosphate, sodium sulfate or magnesium citrate has been assessed in different studies. However, adverse effects limit the use of these agents, particularly in older patients, patients with chronic kidney disease or those on concomitant treatment.57

As far as combining PEG with stimulating agents such as bisacodyl is concerned, a meta-analysis which included six randomised clinical trials found no significant differences in the quality of bowel preparation between patients who received 2l of PEG plus bisacodyl and patients who received 4l of PEG alone, but there was a lower rate of adverse effects in the bisacodyl group.58

Combining PEG with prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide, has not been shown to improve the tolerance or efficacy of bowel preparation, so routine use is not recommended.14

There has also been study of the efficacy of combining osmotic agents other than PEG with stimulating agents. In a clinical trial where patients were randomised to receive sodium picosulfate with magnesium citrate plus bisacodyl or 4l of PEG, no significant differences were found in the quality of bowel preparation, but there was better adherence and satisfaction and there were fewer adverse effects in the group of patients who took the combination.59

A recent meta-analysis, which summarises the existing evidence on the use of adjuvants in bowel preparation, found that the adjuvants improve the quality of the preparation regardless of the administration regimen.17 However, these results need to be interpreted with caution in view of the high degree of heterogeneity between the studies.

Strategies in patients with risk factors for poor bowel preparationAn intensive preparation regimen has been recommended in patients with risk factors for poor bowel preparation.14 However, this recommendation has an empirical basis. Several studies recently assessed the use of specific regimens in patients with some risk factor, with differing results.

History of poor bowel preparationThere is not enough evidence to recommend a specific rescue bowel preparation strategy in patients with a history of poor bowel cleansing.12 The ESGE recommends the use of irrigation pumps during colonoscopy or repeating the procedure the next day after additional preparation13, while the ASGE recommends using large-volume enemas or an additional oral preparation before repeating the procedure.14

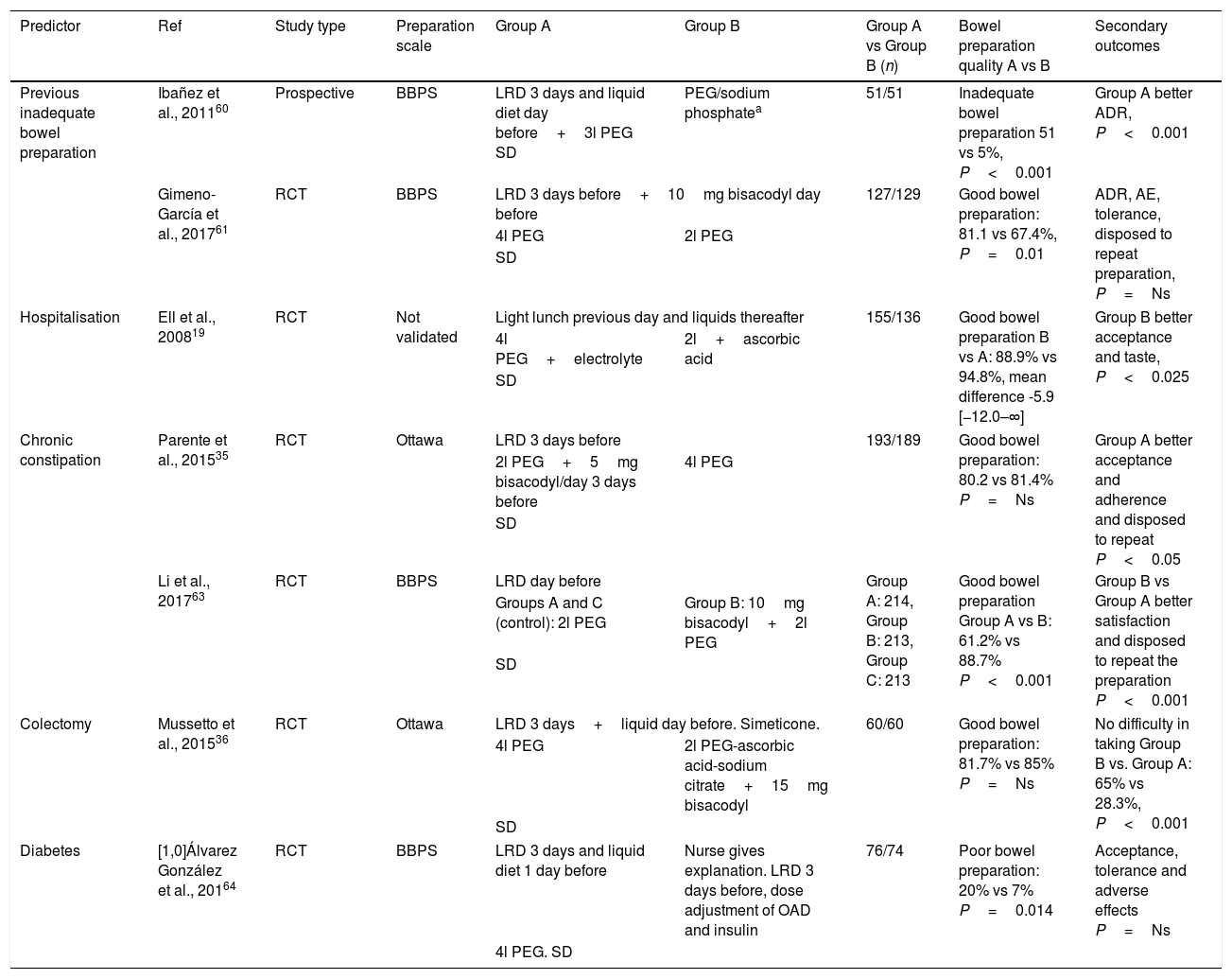

Two prospective studies assessed the use of an intensified preparation strategy based on a low-fibre diet for the three days prior to the colonoscopy and taking 4l of PEG and 10mg of bisacodyl. After using this strategy in 52 patients, Ibañez et al.60 found good bowel preparation in the second colonoscopy in 90.2% of the cases. In a randomised study with a non-inferiority design, Gimeno-García et al.61 compared a high-volume preparation (4l of PEG) with another of low volume (2l of PEG with ascorbic acid). In both cases, 10mg of bisacodyl was given and a low-residue diet recommended for the previous three days. The proportion of patients with adequate bowel cleansing was higher in the high-volume group (81.1% vs 67.4%, p<0.01); with this difference being particularly relevant in the patients given low-volume in the first colonoscopy. No differences were found between the groups in tolerance and/or detection of colorectal lesions (Table 2).

Published studies on intervention strategies in patients with predictive factors of inadequate bowel preparation.

| Predictor | Ref | Study type | Preparation scale | Group A | Group B | Group A vs Group B (n) | Bowel preparation quality A vs B | Secondary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous inadequate bowel preparation | Ibañez et al., 201160 | Prospective | BBPS | LRD 3 days and liquid diet day before+3l PEG SD | PEG/sodium phosphatea | 51/51 | Inadequate bowel preparation 51 vs 5%, P<0.001 | Group A better ADR, P<0.001 |

| Gimeno-García et al., 201761 | RCT | BBPS | LRD 3 days before+10mg bisacodyl day before | 127/129 | Good bowel preparation: 81.1 vs 67.4%, P=0.01 | ADR, AE, tolerance, disposed to repeat preparation, P=Ns | ||

| 4l PEG | 2l PEG | |||||||

| SD | ||||||||

| Hospitalisation | Ell et al., 200819 | RCT | Not validated | Light lunch previous day and liquids thereafter | 155/136 | Good bowel preparation B vs A: 88.9% vs 94.8%, mean difference -5.9 [−12.0–∞] | Group B better acceptance and taste, P<0.025 | |

| 4l PEG+electrolyte | 2l+ascorbic acid | |||||||

| SD | ||||||||

| Chronic constipation | Parente et al., 201535 | RCT | Ottawa | LRD 3 days before | 193/189 | Good bowel preparation: 80.2 vs 81.4% P=Ns | Group A better acceptance and adherence and disposed to repeat P<0.05 | |

| 2l PEG+5mg bisacodyl/day 3 days before | 4l PEG | |||||||

| SD | ||||||||

| Li et al., 201763 | RCT | BBPS | LRD day before | Group A: 214, Group B: 213, Group C: 213 | Good bowel preparation Group A vs B: 61.2% vs 88.7% P<0.001 | Group B vs Group A better satisfaction and disposed to repeat the preparation P<0.001 | ||

| Groups A and C (control): 2l PEG | Group B: 10mg bisacodyl+2l PEG | |||||||

| SD | ||||||||

| Colectomy | Mussetto et al., 201536 | RCT | Ottawa | LRD 3 days+liquid day before. Simeticone. | 60/60 | Good bowel preparation: 81.7% vs 85% P=Ns | No difficulty in taking Group B vs. Group A: 65% vs 28.3%, P<0.001 | |

| 4l PEG | 2l PEG-ascorbic acid-sodium citrate+15mg bisacodyl | |||||||

| SD | ||||||||

| Diabetes | [1,0]Álvarez González et al., 20164 | RCT | BBPS | LRD 3 days and liquid diet 1 day before | Nurse gives explanation. LRD 3 days before, dose adjustment of OAD and insulin | 76/74 | Poor bowel preparation: 20% vs 7% P=0.014 | Acceptance, tolerance and adverse effects P=Ns |

| 4l PEG. SD | ||||||||

ADR, adenoma detection rate; AE, adverse effects; BBPS, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale; LRD, low-residue/low fibre diet; RCT, randomised clinical trial; SD, split dose.

The indication for colonoscopy was mainly screening, endoscopic surveillance or diagnosis.4,35,60 Other indications were surveillance only36, any indication61, or any indication in hospitalised patients.19

It has been found that 22–34% of hospitalised patients undergoing a colonoscopy have inadequate bowel preparation. Predictors of this condition have been low socioeconomic status, the use of opioids and/or tricyclic antidepressants, ASA≥3, nausea and vomiting and age.62 This situation also means an increase in costs deriving from repeated procedures and longer hospital stays.62 One recent prospective, randomised study showed that the good cleanliness rate obtained with low-volume PEG solution was not inferior to high-volume PEG (88.9% vs 94.8%), but the group that received low-volume PEG showed better adherence and tolerance19 (Table 2).

Chronic constipationTwo prospective randomised studies which assessed the effects of adjuvants such as bisacodyl and/or simeticone in combination with PEG-based regimens in patients with chronic constipation found that, although they did seem to improve adherence and patient satisfaction, results were contradictory in relation to improving bowel preparation quality35,63 (Table 2).

ColectomyMost of the studies which have set out to assess bowel preparation strategies have excluded patients with previous bowel resection, so the recommendations for this group are based on expert opinions in favour of high-volume preparations.36 A single prospective, randomised study in patients with a history of colectomy found no significant differences in the quality of bowel preparation obtained with high- or low-volume preparations (85% vs 81.7%). However, better cleanliness was demonstrated in the right colon and better acceptance for taking the preparation in the low-volume group36 (Table 2).

DiabetesPoor bowel cleansing in patients with diabetes has been attributed to the greater frequency of constipation, and also to nausea and vomiting after the ingestion of the preparation solution due to a significant delay in gastric emptying.64 When colonoscopy is indicated in a patient with diabetes, a suitable carbohydrate intake must be ensured to prevent hypoglycaemia during the bowel preparation phase. It would therefore seem appropriate to make adjustments to both diet and treatment. One randomised clinical trial compared the efficacy of a combined strategy (information on bowel preparation from a nurse, low-residue diet for four days, high-volume preparation and treatment adjustment) and a conventional strategy (low-residue diet for three days and high-volume preparation). A higher proportion of the conventional strategy group had poor bowel cleansing (20% vs 7%, p=0.014), with no differences in the adverse effect rate. However, as several strategies (educational, dietary and therapeutic) were combined, the impact of each individual measure on bowel preparation quality cannot be determined4 (Table 2).

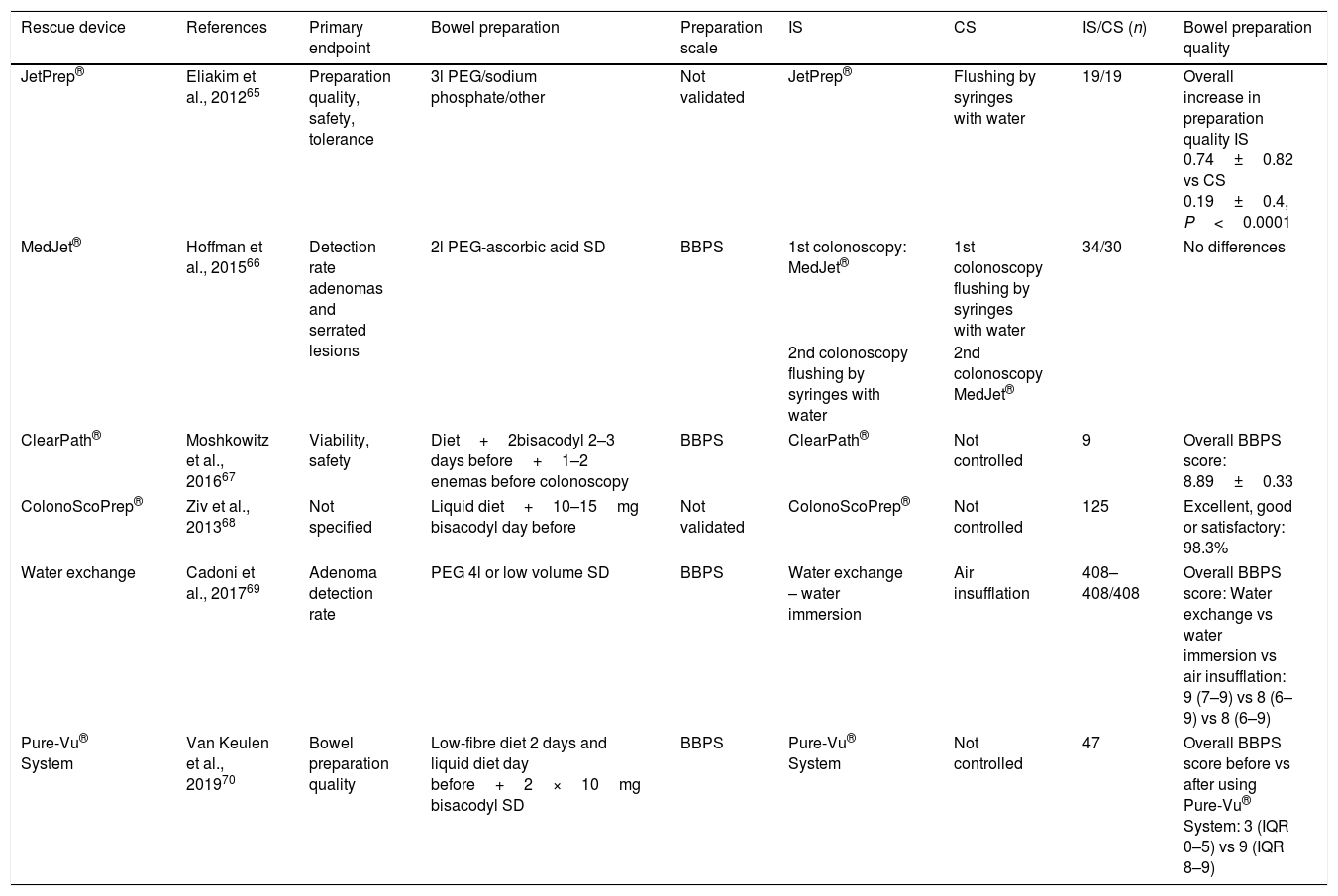

Strategies during colonoscopy to improve the preparationDevices have been developed based on endoscopic irrigation pumps (JetPrep®,65 MedJet®,66 ClearPath®,67 ColonoScoPrep®,68 water immersion69 and Pure-Vu® System) 70using pressurised water, saline solution or even CO2 combined with a suction system which are introduced through the working channel of the endoscope or in parallel to it or can be used prior to the procedure. In general, and in the absence of randomised studies with larger sample sizes, these devices seem to improve the quality of bowel cleanliness (Table 3).

Characteristics of published studies on rescue devices in patients with inadequate bowel preparation.

| Rescue device | References | Primary endpoint | Bowel preparation | Preparation scale | IS | CS | IS/CS (n) | Bowel preparation quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JetPrep® | Eliakim et al., 201265 | Preparation quality, safety, tolerance | 3l PEG/sodium phosphate/other | Not validated | JetPrep® | Flushing by syringes with water | 19/19 | Overall increase in preparation quality IS 0.74±0.82 vs CS 0.19±0.4, P<0.0001 |

| MedJet® | Hoffman et al., 201566 | Detection rate adenomas and serrated lesions | 2l PEG-ascorbic acid SD | BBPS | 1st colonoscopy: MedJet® | 1st colonoscopy flushing by syringes with water | 34/30 | No differences |

| 2nd colonoscopy flushing by syringes with water | 2nd colonoscopy MedJet® | |||||||

| ClearPath® | Moshkowitz et al., 201667 | Viability, safety | Diet+2bisacodyl 2–3 days before+1–2 enemas before colonoscopy | BBPS | ClearPath® | Not controlled | 9 | Overall BBPS score: 8.89±0.33 |

| ColonoScoPrep® | Ziv et al., 201368 | Not specified | Liquid diet+10–15mg bisacodyl day before | Not validated | ColonoScoPrep® | Not controlled | 125 | Excellent, good or satisfactory: 98.3% |

| Water exchange | Cadoni et al., 201769 | Adenoma detection rate | PEG 4l or low volume SD | BBPS | Water exchange – water immersion | Air insufflation | 408–408/408 | Overall BBPS score: Water exchange vs water immersion vs air insufflation: 9 (7–9) vs 8 (6–9) vs 8 (6–9) |

| Pure-Vu® System | Van Keulen et al., 201970 | Bowel preparation quality | Low-fibre diet 2 days and liquid diet day before+2×10mg bisacodyl SD | BBPS | Pure-Vu® System | Not controlled | 47 | Overall BBPS score before vs after using Pure-Vu® System: 3 (IQR 0–5) vs 9 (IQR 8–9) |

BBPS, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale; CS, control strategy; IQR, interquartile range; IS, intervention strategy; PEG, polyethylene glycol; SD, split-dose.

Inadequate bowel preparation negatively affects the efficiency of the colonoscopy, due to the reduced detection rate of colorectal cancer lesions and the need to repeat the procedure. Measures which help improve the quality of bowel cleanliness should therefore be promoted. Hence the suggestion that we need to work towards helping patients to better understand and adhere to the instructions for the colonoscopy through the application of educational strategies. In adherent patients, identification of predictors of inadequate bowel preparation and the use of predictive models could help select patients who might benefit from intensified bowel preparation strategies and/or the addition of adjuvants (Appendix 1). Last of all, we need well-designed studies to assess the use and effectiveness of the new rescue devices.

FundingGoretti Hernández was funded by a Professional Practices in Medicine grant from Fundación MAPFRE Guanarteme.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

- •

A history of inadequate bowel cleansing should be sufficient reason for prescribing intensified bowel preparation in patients with good compliance and who tolerate the preparation.14

- •

The application of predictive models of poor bowel cleansing could be a useful tool for optimising the quality of bowel preparation in clinical practice.28,33,34

- •

The use of additional educational material such as leaflets, videos, phone calls/text messages or mobile applications increases bowel preparation quality6,39 and could be useful in patients with predictive factors of inadequate preparation.

- •

Intensified bowel preparation based on low-fibre diet for three days plus 10mg of bisacodyl and 4l of PEG in split dose has been shown to be superior to PEG-based low volume preparations in patients with a history of poor bowel preparation.61

- •

In diabetic patients, a multifactorial strategy based on a personalised interview with nurses, low-residue diet for four days, high-volume preparation and adjustment of antidiabetic treatment/insulin therapy has been shown to improve bowel preparation quality.4

Please cite this article as: Hernández G, Gimeno-García AZ, Quintero E. Estrategias para optimizar la calidad de la limpieza colónica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:326–338.