The use of esophageal stents for the endoscopic management of esophageal leaks and perforations has become a usual procedure. One of its limitations is its high migration rate. To solve this incovenience, the double-layered covered esophageal stents have become an option.

ObjectivesTo analyse our daily practice according to the usage of double-layered covered esophageal metal stents (DLCEMS) (Niti S™ DOUBLE™ Esophageal Metal Stent Model) among patients diagnosed of esophageal leak or perforation.

MethodsRetrospective, descriptive and unicentric study, with inclusion of patients diagnosed of esophageal leak or perforation, from November 2010 until October 2018. The main aim is to evaluate the efficacy of DLCEMS, in terms of primary success and technical success. The secondary aim is to evaluate their (the DLCEMS) safety profile.

ResultsThirty-one patients were firstly included. Among those, 8 were excluded due to mortality not related to the procedure. Following stent placement, technical success was reached in 100% of the cases, and primary success, in 75% (n = 17). Among the complications, stent migration was present in 21.7% of the patients (n = 5), in whom the incident was solved by endoscopic means.

ConclusionsAccording to our findings, DLCEMS represent an alternative for esophageal leak and perforation management, with a high success rate in leak and perforation resolutions and low complication rate, in contrast to the published data. The whole number of migrations were corrected by endoscopic replacement, without the need of a new stent or surgery.

El uso de prótesis esofágicas para el manejo endoscópico de fístulas y perforaciones se ha convertido en un procedimiento habitual. Una de sus limitaciones es su alta tasa de migración. Para resolver esta situación, se ha propuesto el uso de prótesis cubiertas de doble malla.

ObjetivosAnalizar nuestra experiencia práctica en el empleo de prótesis esofágicas cubiertas de doble malla (PECDM) (modelo Niti S™ DOUBLE™ Esophageal Metal Stent) en pacientes con fístula o perforación esofágica.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo, descriptivo y unicéntrico, donde se incluyen pacientes con diagnóstico de fístula o perforación esofágica, desde noviembre 2010 hasta octubre 2018. Como objetivo primario, se evaluará su eficacia en términos de éxito técnico. Como objetivo secundario, se analizará su perfil de seguridad.

ResultadosSe incluyeron inicialmente un total de 31 pacientes, siendo 8 de ellos excluidos por fallecimiento por causas ajenas a la técnica. Se detectó un éxito técnico del 100%, con un éxitoprimario del 75% tras la recolocación de la prótesis. Entre sus complicaciones, la migración ocurrió en un 21,7% de los pacientes (n = 5), resolviéndose vía endoscópica en el 100% de los casos.

ConclusionesSegún nuestros hallazgos, las PECDM suponen una alternativa en el tratamiento de fístulas y perforaciones esofágicas, con una alta tasa de éxito en la resolución de fístulas y baja de complicaciones, en contraste con lo expuesto en las series publicadas. En todos los casos, la migración de la prótesis se resolvió mediante recolocación endoscópica, sin requerir nueva prótesis ni cirugía.

The vast majority of oesophageal fistulas and perforations are the result of surgical interventions for oesophagogastric disease, of both benign and malignant aetiology. A prevalence of up to 4%–27% has been described in patients after radical gastrectomy, and in 5%–18% of patients after oesophagectomy.1–3 These complications involve high rates of morbidity, with an increase in hospital stay, admissions to intensive care units, and a mortality of between 12 and 50% of patients.4–6

Years ago, endoscopic management of these lesions represented a great advance in the prognosis of these patients, both in terms of therapeutic success and survival. The use of oesophageal prosthetics or stents involved less technical difficulty, with significantly lower morbidity and mortality than surgical techniques.7,8

Characteristically, covered self-expanding metal stents have been used, obtaining efficacy rates, defined as complete closure of the lesion, of 60%–90%.3,9 Their main drawback is the high percentage of migration, which ranges between 13 and 50% depending on the different series.5,10 This is the cause of a significant part of therapeutic failures and a significant cost overrun. Subsequently, plastic prostheses were developed with the aim of facilitating their removal, also observing high rates of migration,11 as well as biodegradable prostheses, although at the moment we do not have enough studies and results to support their use in daily practice.12 For this reason, the use of partially-covered oesophageal stents has spread, and these achieve a lower migration percentage at the expense of notably increasing the technical difficulty of removal.13 This is due to the intraluminal mucosal growth at the uncovered ends of the prosthesis, which in turn leads to an increased incidence of dysphagia after extraction.3,7

As an alternative, and with the aim of combining the benefits of the previous ones, double mesh fully-covered self-expanding metal stents (FCSEMS) were developed. These are made up of an external mesh of nitinol, a nickel and titanium alloy, which enables adherence to the surrounding tissues, as well as an internal polyurethane cover that seals the fistula and allows for its removal.14

FCSEMS emerged more than 10 years ago with a view to implementing the results in the palliative treatment of dysphagia due to oesophagogastric neoplasms at the cost of reducing the incidence of migration and obstruction due to tumour growth. This hypothesis has been confirmed a posteriori in various studies.14–16 In view of these results, we have extrapolated the use of self-expanding metal stents to benign disease.

To date, we do not have any studies that assess the technical and therapeutic success in these patients, it being limited to isolated cases.10 However, the data currently available in malignant disease show a similar efficacy compared to partially-covered prostheses, with a significantly lower incidence of migration that could substantially improve the results in these patients.14–16

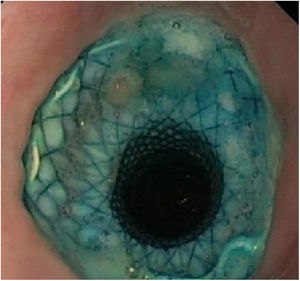

The FCSEMS (Niti-S™ DOUBLE™ Esophageal Metal Stent model) has a repositioning and withdrawal mechanism, and the external mesh exposed in its central area reduces the rate of migration. In addition, since the body of the prosthesis is completely covered, it prevents the growth of tissue through the holes in the mesh, which prevents its obstruction. For this reason, with this study we intend to evaluate the efficacy of these prostheses in fistulas and oesophageal perforations, and the complications associated with their use.

ObjectivesOur main objective is to evaluate the effectiveness (technical success) of FCSEMS (Niti S™ DOUBLE™ Esophageal Metal Stent model) in the treatment of non-neoplastic oesophageal or oesophagogastric fistulas.

The secondary objectives are to analyse their safety profile in our clinical practice, based on the presence of subsequent complications, and particularly, on the migration rate of the prosthesis.

Material and methodsThis is an observational, retrospective, single-centre study following our experience in the use of FCSEMS (Niti S™ DOUBLE™ Esophageal Metal Stent model) from October 2010 to November 2018.

Carriers of FCSEMS (Niti S™ DOUBLE™ Esophageal Metal Stent model) were included after endoscopic or radiological diagnosis of perforation or oesophageal or gastroesophageal fistula of multifactorial origin, excluding only those of neoplastic origin.

The procedures were performed under deep sedation by three expert endoscopists, with those performed less than 24 h after diagnosis of the lesion considered urgent. The placement of the prostheses was guided by endoscopy and fluoroscopy, with their release parallel to the endoscope.

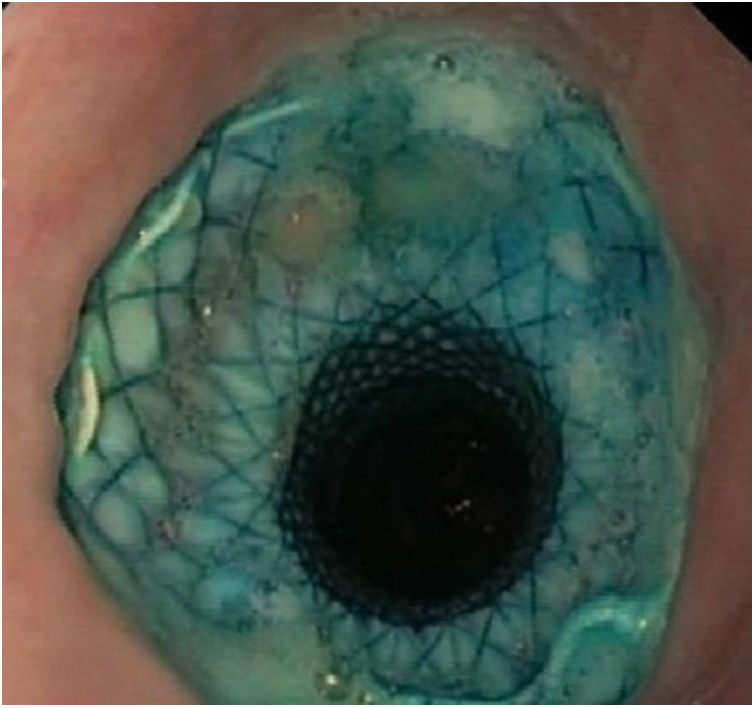

The specific FCSEMS model used is made up of two layers of nitinol mesh, an inner one, completely covered in silicone, and an outer one, totally uncovered. It has a loop at its proximal end to facilitate its repositioning or removal. Likewise, it has four opaque radiotracers at each end and two in the centre to facilitate its placement by fluoroscopy (Fig. 1). The stent is distal-release.

The variables of age, sex, characteristics (length, diameter) and indication for placement of the prosthesis, the result obtained expressed by technical success, time until its removal, as well as complications derived from the technique, were analysed.

We define technical success as the complete closure of the fistula or perforation, confirmed endoscopically, at the time of its removal; it being primary if it has not required the placement of a new prosthesis, or it was solved with its repositioning, and secondary if a second prosthesis or different endoscopic method was required to achieve its closure.

Regarding complications, migration was defined as displacement of the prosthesis from its insertion site, it being partial if the prosthesis was able to be repositioned endoscopically, and complete if it was necessary to place a new one.

Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages; and continuous variables, such as mean and standard deviation were analysed with the SPSS® programme, version 21.

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto Aragonés de Ciencias de la Salud [Aragón Health Sciences Institute].

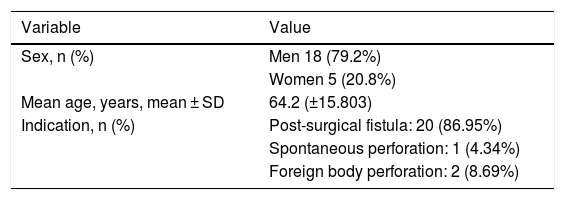

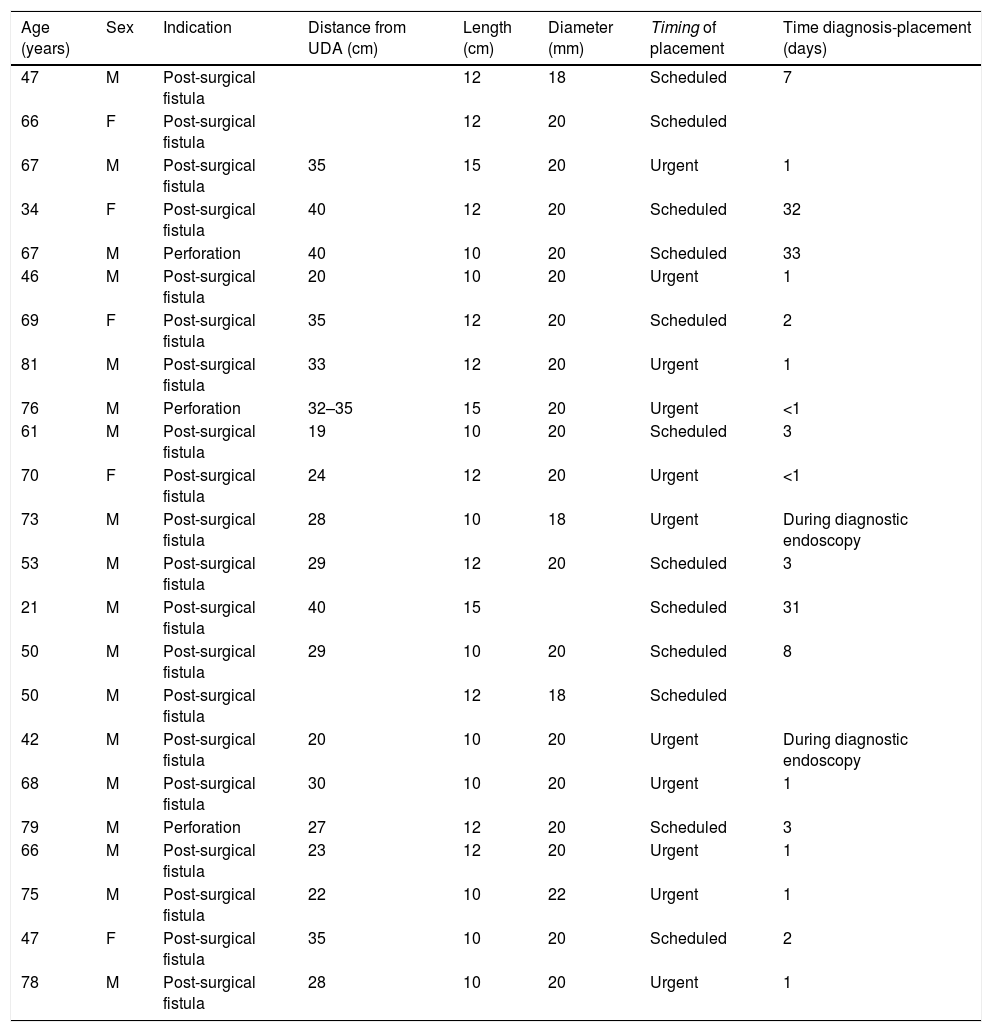

ResultsAn initial sample of 31 patients was analysed. Eight patients were subsequently excluded due to lack of follow-up due to death. In all cases, death occurred due to causes unrelated to the technique (Fig. 2). Of the final sample, the mean age was 64.2 years, with 79.2% being men (n = 18). The indication for FCSEMS placement was postoperative oesophageal or oesophagogastric fistula in 86.95% of those (n = 20), and oesophageal perforation due to a foreign body in 8.69% (n = 2), and spontaneous (Boerhaave syndrome) in the remaining 4.34% (n = 1) (Tables 1 and 2). They were placed urgently in 47.82% of cases (n = 11).

Indications and characteristics of the prostheses used.

| Age (years) | Sex | Indication | Distance from UDA (cm) | Length (cm) | Diameter (mm) | Timing of placement | Time diagnosis-placement (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 12 | 18 | Scheduled | 7 | |

| 66 | F | Post-surgical fistula | 12 | 20 | Scheduled | ||

| 67 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 35 | 15 | 20 | Urgent | 1 |

| 34 | F | Post-surgical fistula | 40 | 12 | 20 | Scheduled | 32 |

| 67 | M | Perforation | 40 | 10 | 20 | Scheduled | 33 |

| 46 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 20 | 10 | 20 | Urgent | 1 |

| 69 | F | Post-surgical fistula | 35 | 12 | 20 | Scheduled | 2 |

| 81 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 33 | 12 | 20 | Urgent | 1 |

| 76 | M | Perforation | 32–35 | 15 | 20 | Urgent | <1 |

| 61 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 19 | 10 | 20 | Scheduled | 3 |

| 70 | F | Post-surgical fistula | 24 | 12 | 20 | Urgent | <1 |

| 73 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 28 | 10 | 18 | Urgent | During diagnostic endoscopy |

| 53 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 29 | 12 | 20 | Scheduled | 3 |

| 21 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 40 | 15 | Scheduled | 31 | |

| 50 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 29 | 10 | 20 | Scheduled | 8 |

| 50 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 12 | 18 | Scheduled | ||

| 42 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 20 | 10 | 20 | Urgent | During diagnostic endoscopy |

| 68 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 30 | 10 | 20 | Urgent | 1 |

| 79 | M | Perforation | 27 | 12 | 20 | Scheduled | 3 |

| 66 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 23 | 12 | 20 | Urgent | 1 |

| 75 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 22 | 10 | 22 | Urgent | 1 |

| 47 | F | Post-surgical fistula | 35 | 10 | 20 | Scheduled | 2 |

| 78 | M | Post-surgical fistula | 28 | 10 | 20 | Urgent | 1 |

Diagnosis-placement time: time between diagnosis and placement (blank box: data not available); F: female; M: male; UDA: upper dental arch.

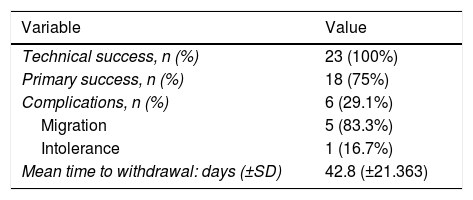

Technical success or closure of the fistula occurred in 100% of the patients, with a primary success rate of 62.5% (n = 15), and reaching 75% (n = 18) after endoscopic repositioning of the prosthesis. In the remaining patients (n = 5), the fistula persisted after stent removal, requiring a second FCSEMS (n = 4), as well as the placement of a haemoclip (n = 1). The mean time for the prosthesis being in place (stenting time) was 42.8 days (SD: ±21.363) (Table 3).

Results after FCSEMS placement.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Technical success, n (%) | 23 (100%) |

| Primary success, n (%) | 18 (75%) |

| Complications, n (%) | 6 (29.1%) |

| Migration | 5 (83.3%) |

| Intolerance | 1 (16.7%) |

| Mean time to withdrawal: days (±SD) | 42.8 (±21.363) |

FCSEMS: fully-covered (double mesh) self-expanding metal (oesophageal) stents; SD: standard deviation.

Regarding its safety profile, complications were recorded in 29.1% of patients (n = 6). In 21.7% (n = 5) migration of the prosthesis was observed: in three cases it was partial and in two cases it was complete. In all cases, the fistula was resolved endoscopically: after repositioning the migrated prosthesis, or after inserting a new stent (Figs. 3 and 4). In one patient the prosthesis had to be removed after two weeks due to intolerance to it (persistent chest pain), although despite its early removal, the fistula had already closed.

In no case was prosthesis dysfunction due to intra- or peri-prosthetic tissue growth observed, nor was any death recorded in relation to the technique.

DiscussionThe management of oesophageal fistulas is a challenge for physicians, as it is commonly the result of a complex previous surgical intervention, and aggravated by a frail patient with significant associated comorbidity.

According to the latest clinical guidelines on the management of stents in benign and malignant oesophageal disease from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), the use of covered oesophageal prostheses is an effective therapeutic option for the management of oesophageal fistulas and perforations.13 Their duration is still not well defined, although in most studies they are withdrawn between the sixth and eighth week,17,18 following the same line as in our centre.

The FCSEMS emerged with the aim of resolving the most common complications derived from the use of prostheses in oesophageal disease: migration and re-stenosis due to intra- or peri-prosthetic tissue growth. Initially intended for use in malignant strictures, their repositioning mechanism makes it possible to remove them easily, which means they are suitable for the treatment of benign oesophageal disease.

In several studies, a rate of complications associated with the placement of fully covered prostheses of 34% has been described.4,14 The most common is it migrating, which, according to a recently published meta-analysis, can occur in up to 23% of cases (95% CI: 19%–28%).19 In our series, the use of FCSEMS demonstrated a low migration rate (21.73% of the total, three partial: 13% and two complete: 8.69%), which is below the average of what has been published to date, and also taking into account that it is not a FCSEMS designed specifically for the closure of post-surgical fistulas.

However, in another recently published study, a migration rate of 38.2% is described (13/34 stents), with 53.8% (7/13 stents) partially migrating, concluding that the technical and clinical success of the use of covered self-expanding oesophageal stents is very high, and even seems to be independent of whether or not there is migration of the stents.20

In our series, three of the five migrations that occurred (60%) were partial and were corrected by endoscopic repositioning of the stent, without incident. No cases of intra- or peri-prosthetic tissue growth causing FCSEMS dysfunction were recorded. Finally, technical success was achieved with one or two prostheses in 95.6% (n = 22) of patients (a single prosthesis in 75% of cases), endoscopic resolution of the fistula being achieved in 100% (in one case haemoclip placement was required). No case required surgical re-intervention, and all complications were resolved by endoscopy.

However, our study has a series of limitations. Firstly is its retrospective nature. Secondly is the small sample size available, although the use of FCSEMS in benign oesophageal pathology is not as common in daily practice, and our series is the largest published to date with this type of prosthesis.

In the future, biodegradable prostheses, as they do not require removal or repositioning in case of migration, could be an alternative, although there are still not enough studies to support their use, and cases of dysphagia and stenosis due to mucosal reactivity have been described.12,21,22

ConclusionsThe FCSEMS represents a minimally invasive treatment, which is effective and safe, for the management of oesophageal fistulas and perforations, with a high rate of success and few complications, which contrasts with what has been discussed in published series. In our series, a complete migration rate similar to or lower than that reported in previous studies is notable,14 all of them resolved endoscopically without requiring surgery, with no prosthetic dysfunction secondary to tissue growth.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sanz Segura P, Gotor Delso J, García Cámara P, Sierra Moros E, Val Pérez J, Soria Santeodoro MT, et al. Uso de prótesis esofágicas cubiertas de doble malla en fístulas esofágicas postquirúrgicas y perforaciones esofágicas: experiencia en nuestro centro. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:198–203.