Chronic pancreatitis is associated with impaired quality of life, high incidence of comorbidities, serious complications and mortality. Healthcare costs are exorbitant. Some medical societies have developed guidelines for treatment based on scientific evidence, but the gathered level of evidence for any individual topic is usually low and, therefore, recommendations tend to be vague or weak.

In the present position papers on chronic pancreatitis from the Societat Catalana de Digestologia and the Societat Catalana de Pàncrees we aimed at providing defined position statements for the clinician based on updated review of published literature and on multidisciplinary expert agreement. The final goal is to propose the use of common terminology and rational diagnostic/therapeutic circuits based on current knowledge. To this end 51 sections related to chronic pancreatitis were reviewed by 21 specialists from 6 different fields to generate 88 statements altogether. Statements were designed to harmonize concepts or delineate recommendations.

Part 2 of these paper series discuss topics on treatment and follow-up. The therapeutic approach should include assessment of etiological factors, clinical manifestations and complications. The complexity of these patients advocates for detailed evaluation in multidisciplinary committees where conservative, endoscopic, interventional radiology or surgical options are weighed. Specialized multidisciplinary units of Pancreatology should be constituted. Indications for surgery are refractory pain, local complications, and suspicion of malignancy. Enzyme replacement therapy is indicated if evidence of exocrine insufficiency or after pancreatic surgery. Response should be evaluated by nutritional parameters and assessment of symptoms. A follow-up program should be planned for every patient with chronic pancreatitis.

La pancreatitis crónica se asocia a calidad de vida deteriorada, elevada incidencia de comorbilidades, complicaciones graves y mortalidad. Los costes sanitarios son enormes. Algunas sociedades médicas han elaborado guías clínicas basadas en evidencia científica, pero el nivel de evidencia para cada aspecto de la enfermedad suele ser bajo y, consecuentemente, las recomendaciones tienden a ser vagas o débiles.

En los presentes documentos de posicionamiento de la Societat Catalana de Digestologia y la Societat Catalana de Pàncrees hemos buscado redactar declaraciones bien definidas orientadas al clínico, basadas en revisiones actualizadas de la literatura y acuerdos de expertos. El objetivo es proponer el uso de terminología común y circuitos diagnóstico/terapéuticos racionales basados en el conocimiento actual. Para este fin se revisaron 51 secciones relacionadas con pancreatitis crónica por 21 expertos de 6 especialidades diferentes para generar finalmente 88 declaraciones que buscan armonizar conceptos y formular recomendaciones precisas.

La parte 2 de esta serie de documentos discute temas sobre tratamiento y seguimiento. La aproximación terapéutica debe incluir la evaluación de factores etiológicos, manifestaciones clínicas y complicaciones. La complejidad de estos pacientes requiere un estudio detallado individualizado en comités multidisciplinares donde todas las opciones (conservadoras, endoscópicas, de radiología intervencionista y quirúrgicas) sean sopesadas. Deberían constituirse unidades especializadas de pancreatología. Las indicaciones quirúrgicas son dolor refractario, complicaciones locales y sospecha de neoplasia. El tratamiento enzimático está indicado si existe evidencia de insuficiencia exocrina o tras cirugía pancreática. La respuesta debe evaluarse mediante parámetros nutricionales y síntomas. Se debe planificar un programa de seguimiento para cada paciente.

This is the second of a series of 3 documents aiming at highlighting the main concepts and actions recommended by the Societat Catalana de Digestologia [Catalan Gastroenterology Society] (SCD) and the Societat Catalana de Pàncrees [Catalan Pancreas Society] (SCPanc) on clinical topics of chronic pancreatitis (CrP). The goal is to propose a common terminology and rational diagnostic and therapeutic circuits based on current knowledge. The number of sections reviewed, the number of participating specialists and qualitative composition was already specified in the first document of the series on aetiology and diagnosis of CrP.1

From the updated review of the sections, a preliminary manuscript was drawn up that was later discussed by the entire group. Whenever discrepancies among group members were detected, the text was edited in order to achieve a consensus greater than 90%. The document was later presented to the two sponsoring societies for their approval. The phrases preceded by the abbreviation SCD-SCPanc indicate the position of the two organizations in the different statements, either to emphasize a concept or to express a recommendation.

Treatment of chronic pancreatitisSCD-SCPanc 1. The therapeutic approach to all patients with chronic pancreatitis should include a detailed assessment of possible etiological factors as well as clinical manifestations and complications.

SCD-SCPanc 2. As a general rule, removal of etiological factors associates with improved disease outcome.

Patients who stop drinking and smoking have a better prognosis.2,3 Those who maintain their toxic habits have an accelerated evolution of the disease, more attacks of pancreatitis, form calcifications more quickly and tend to develop endocrine insufficiency. Quitting smoking (or drinking) may be essential to minimize future bouts of pancreatitis in patients with genetic mutations or groove pancreatitis.

Proper treatment of hypertriglyceridemia prevents repeated pancreatitis and episodes of necrotizing pancreatitis.

Definitive resolution of a ductal obstruction is followed by an improved outcome.4

Treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis improves symptoms and can reverse morphological lesions. In some cases, improvement in exocrine and endocrine insufficiency has been documented.

As for today, we still do not have specific treatments that reverse the abnormalities derived from genetic alterations associated with chronic pancreatitis.

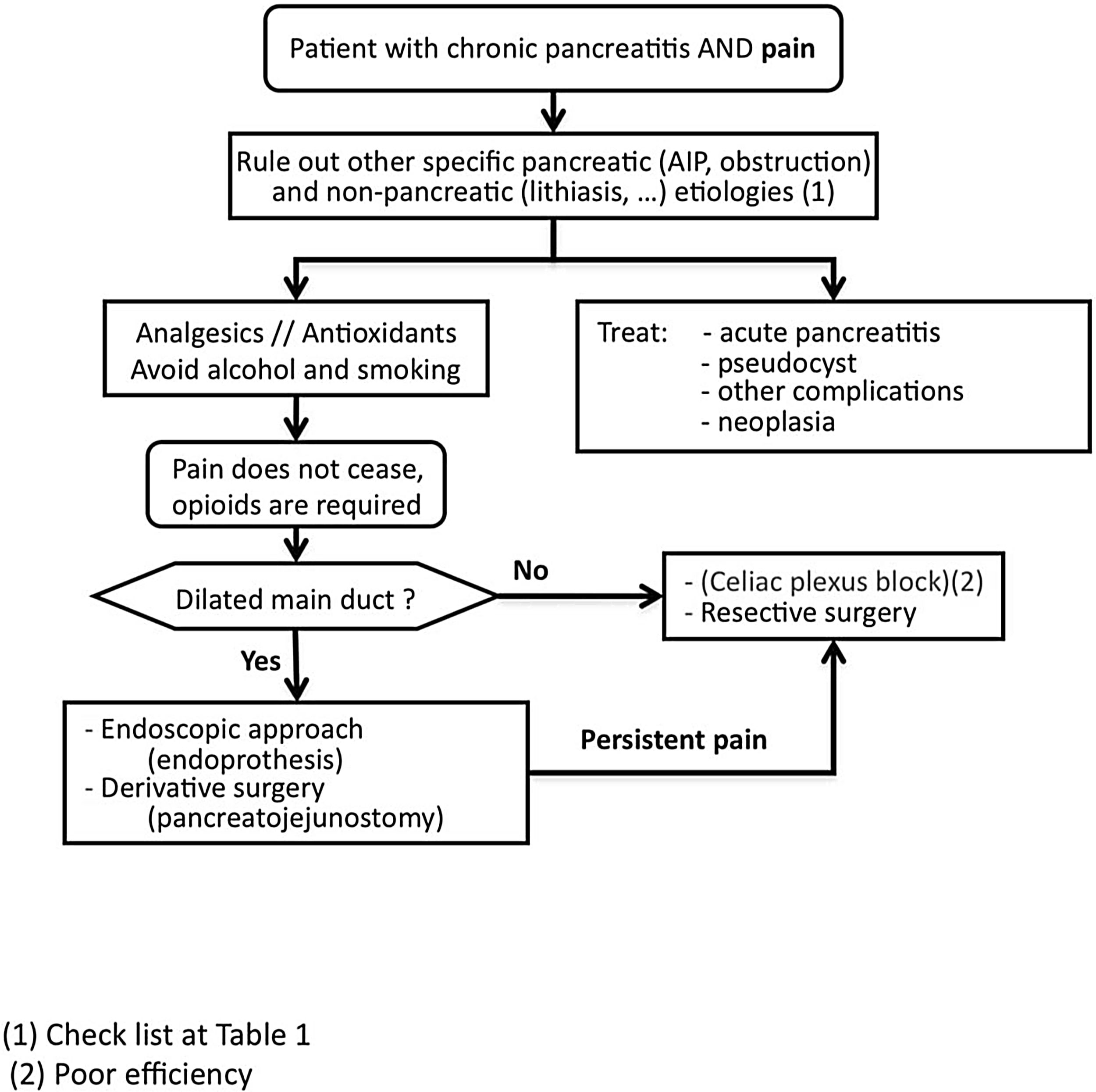

Pain managementSCD-SCPanc 3. We advise planning pain management with a rational and sequential combination of therapeutic modalities (Diagram 1).

SCD-SCPanc 4. We recommend that the analgesic regimen conform to the guidelines of the WHO analgesic ladder, using effective dosage at appropriate intervals and adjusting the doses to the intensity of pain.

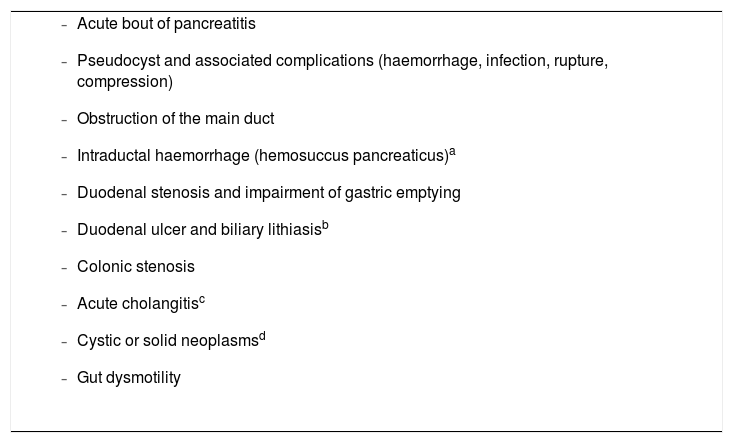

Pain should be treated with effective drugs in appropriate therapeutic dosages. Causes of pain requiring specific approaches should be investigated (Table 1).

Complications associated with chronic pancreatitis that may cause or amplify pancreatic pain.

|

Pain in chronic pancreatitis can have a specific origin or recognize multifactorial components (inflammation, increased parenchymal or ductal pressure, neurogenic sensitization). For this reason, treatment strategies, including pharmacological ones, must take into account the possible pain components in order to design the most realistic approach.

It is always advisable to characterize the patient's pain, particularly before initiating any therapeutic intervention in order to better assess its efficacy. One-dimensional (0–10 numerical scale, visual analogue scale) or multidimensional (Brief Pain Inventory, McGill Pain Questionnaire) scales can be used. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) can detect whether central sensitization of chronic pancreatic pain (segmental or diffuse) has developed and thus better guide treatment approaches.5–7

The etiological factors associated with CrP may influence the response to treatment.3 For this reason it should always be recommended that the patient stop drinking alcohol and smoking.

Apart from treating etiological factors (especially ductal obstruction, tobacco, alcohol and autoimmunity) it is also advisable to follow a healthy diet and promote exercise as long-term therapeutic measures. Antioxidants may be beneficial in non-smoking patients.2,8

The efficacy of pancreatic enzymes for pancreatic pain is controversial. A 2-month trial treatment is acceptable, but this is a weak recommendation.

The treatment regimen usually begins with the first step of the WHO analgesic ladder.2,3,8,9

As pain in CrP is irregular and intermittent, it is important to monitor analgesic dosage. Any medication administered in the absence of pain is an unnecessary overdose.

We can start with paracetamol 500–1000 mg every 4–6 h (≤4 g/day) while monitoring the appearance of liver toxicity, the risk of which is greater in alcoholic patients. The use of metamizole (0.5–2 g/6–8 h, with a daily maximum of 8 g) is questioned due to its role in the development of blood dyscrasias.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are effective, but they can induce gastroduodenal lesions and kidney failure. Therefore their prolonged use is not recommended.

Paracetamol associated with codeine (60 mg/4–6 h) or tramadol (50–150 mg/4–6 h) has greater analgesic strength. Gastrointestinal motility is less affected by tramadol than by codeine.

The addition of antidepressants, anticonvulsants or pregabalin (25–75 mg/day) has been shown to be effective in selected patients, but induces frequent adverse effects. Before applying this treatment modality, a quantitative sensory test can be performed (in centres that have standardized this test) that is capable of detecting neuroplastic changes of central pain sensitization.7 These changes anticipate a poor response to the classical pharmacological approach to pain and justify the introduction of some other drugs such as pregabalin.10

If the pain is not controlled either, the treatment regimen may proceed to the next step, which consists of the time-restricted administration of major opioids, such as oral morphine 10–40 mg/4 h, always adjusting the dose to the intensity of the pain. As alternatives we can use MST morphine, 10–40 mg/8–12 h; oxycodone, 10–40 mg/12 h; or buprenorphine, 0.2–0.4 mg/6−8 h sublingually or 0.3–0.6 mg/6–8 h i.m. When prescribing opiates, we must be very careful to avoid overdosing in patients who already tend to have addictive predisposition (smokers, alcoholics) and with the development of side effects (respiratory depression, constipation).

As the intensity of pain is variable and intermittent, prolonged-release opioids (patches) are not recommended due to the risk of inducing habituation and dependence. On the other hand, it has been shown that response to more aggressive options for pain management (such as bypass or resection surgery) has worse results in patients who have already initiated treatment with opiates.

Spinal cord stimulation11 may have a beneficial effect in the control of chronic pancreatic pain and in reducing the use of opioids.

If treatable causes are not identified, the pain is not controlled with conventional analgesia and the use of opioids is required, invasive treatments such as neural blockade, endoscopic or surgical interventions are indicated. Invasive interventions are reserved for those patients with frequent attacks of pain and evident morphological changes (inflammatory mass, pancreatic duct dilation, etc.). In addition, it is recommended that these treatment modalities be carried out in specialized centres with proven expertise.

Endoscopic pain managementSCD-SCPanc 5. In the early stages of the disease, an endoscopic approach can be considered as the first option for invasive pain treatment. This approach is reinforced when appearance or increase of pain is associated to morphological changes or progression of established lesions.

SCD-SCPanc 6. We recommend that endoscopic treatment should considered as a first option when surgery is contraindicated (severe cardiovascular disease or bronchopathy, segmental portal hypertension) and collections, duct stenosis or accessible ductal calculi can be approached. The presence of an inflammatory mass advises against endoscopic treatment.

Before indicating a bypass surgery, it is acceptable to first consider endoscopic treatment and evaluate the results. This argument has generated much debate in the last 10 years because several prospective randomized studies have shown better results in pain control using surgical techniques.4 On the other hand, an early reasoned surgery (e.g., on a fibrous ductal obstruction) can resolve the pain definitively and avoid the development of central pain sensitization.

However, endoscopic treatment can be definitive, or it can be used as a bridge before aggressive surgery. Furthermore, it is not uncommon patients may present relative or absolute contraindications to surgery, as in the case of segmental portal hypertension or severe cardiovascular disease or bronchopathy. In these cases endoscopic approaches play a greater role.12

Endoscopic procedures include placing a stent in the main pancreatic duct after pancreatic sphincterotomy and dilatation of stenosis, fragmentation and removal of intraductal calculi, and drainage of fluid collections, whenever these pathologies are suspected to be the origin of symptoms.

The stenoses and calculi for optimal endoscopic treatment are those located in the area close to the papilla, while the most proximal ones are less accessible. Stents placed with the intention of dilating stenosis or draining the main pancreatic duct or a fluid collection can be replaced at set intervals. Long-term pain relief ranges between 50% and 60%.12 If there is dilation of the main duct secondary to stenosis or distal lithiasis that are not accessible via the transpapillary route, an attempt can be made to access the main duct through EUS-guided transgastric puncture in specialized centres.

If there is an inflammatory mass in the head of the pancreas, endoscopic interventions are usually not effective in pain treatment.

Some endoscopic procedures will be explained in more detail when addressing some complications of chronic pancreatitis (Part 3).

Surgical pain managementSCD-SCPanc 7. Surgery is indicated when other procedures have failed, the patient requires continuous major opioids or there is a suspicion of neoplasia.

SCD-SCPanc 8. The surgical technique to be applied is decided based on:

- -

Presence of ductal dilation (>5 mm in diameter or diffuse dilation) and ductal stenosis/calculi.

- -

Presence and location of inflammatory mass, especially at the pancreatic head. An increase of more than 40 mm in its anteroposterior diameter is considered pathological.

- -

Involvement and stenosis of peripancreatic tissues (bile duct, duodenum, colon, mesenteric-portal venous confluence).

- -

Presence of portal hypertension.

Several studies indicate that surgical modalities are the most effective modality for the treatment of persistent pain in patients with CrP. They are more effective than endoscopic approaches, but they are associated to complications and can be technically difficult, especially if there is portal hypertension. Early surgical intervention has even been recommended in order to obtain a greater benefit,4 way before serious complications may arise that could add greater complexity to surgical interventions, and before central sensitization may develop. Best results are achieved during the first 3 years after the onset of pain and when opioid treatment has not yet been iniciated.2,4,13–15

Surgical options are grouped into three categories: derivative, resective and mixed techniques.

Derivative techniquesThese are indicated when the size of the pancreatic head is normal and there is a dilatation of the main pancreatic duct >5 mm.

The most commonly used surgical technique in this category is the Roux Y-shaped side-to-side pancreatojejunostomy: the modified Puestow or Partington-Rochelle procedure. Longitudinal opening of the main duct is performed on the anterior side of the pancreas, potential calculi are then extracted or fragmented, and side-to-side anastomosis with a defunctional jejunum loop is performed. Good results have been reported using this technique on pain control, with 75% clinical improvement. Mortality rates are only 1–4% and morbidity rates less than 30%.16

Comparative studies using endoscopic stenting have reported better results for surgery.17,18

Resection techniquesThese surgical techniques are indicated when there is an increase in the size of the pancreatic head of more than 40 mm or in the case of groove pancreatitis. They show great long-term results in terms of pain control. We can consider 3 modalities:

- 1

Cephalic duodenopancreatectomy (Whipple procedure). This is the most commonly used procedure.

- 2

Cephalic duodenopancreatectomy with pyloric preservation (Traverso procedure)

- 3

Cephalic pancreatectomy with duodenal preservation (Beger procedure). In this case, the effectivity for pain control is high (90%), but at the cost of high morbidity (40%).

In the Whipple procedure, resection of the pancreatic head is associated with removal of the duodenum and the distal bile duct. It is not exempted from complications and the associated mortality is close to 5%.

Mixed techniquesThey are indicated when fibroinflammatory lesions in the pancreatic head are associated with main duct dilation.13 The most widely used of these techniques is partial pancreatic head resection with side-to-side pancreatojejunostomy (Frey's procedure). It achieves good results (90% effectivity in pain control), low morbidity (23%) and low mortality (0.4%).

Total pancreatectomy is a surgical option that is considered to perform very rarely, when other procedures have failed or evaluated for patients with intractable pain without ductal dilation or focal inflammatory involvement. It results in difficult-to-control diabetes that islet autotransplantation can mitigate, but not control completely, since insulin needs at 5 years are 55% and 90% at 8 years.19,20

Procedures intended to discontinue neural transmission of painSCD-SCPanc 9. Interruption of neural transmission is considered an alternative measure to endoscopic and surgical treatments. We only recommend it if applied in specialized centres and when other therapeutic measures have failed or are impracticable.

It is a not quite appealing therapeutic option because it only reduces (but does not eliminate) pain in 60–70% of cases during the first months, its effectivity fades over time and it is not without side effects.

Two modalities are used:

- 1

Blockade or celiac plexus neurolysis. A needle guided by CT or EUS is inserted in close proximity to the celiac plexus where bupivacaine and corticosteroids (blockade) or bupivacaine and alcohol (neurolysis) are infused.21

- 2

Thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy. The neural bundles are sectioned at the level of the thorax.

The effectivity of celiac plexus blockade in chronic pancreatitis does not usually exceed 60% and most patients continue to require analgesics. Furthermore, the reduction in pain that is achieved does not usually last more than 3 months.2,21,22 It is a procedure that can be associated with unpleasant side effects, such as postural hypotension and diarrhoea.

Other procedures intended to treat pancreatic pain could be effective in selected cases, such as spinal stimulation,11 transcranial magnetic stimulation and acupuncture.

Treatment of exocrine insufficiency (EPI)SCD-SCPanc 10. Enzyme replacement therapy is justified in patients with symptomatic steatorrhea, in cases of documented evidence of EPI or after pancreatic surgery.

SCD-SCPanc 11. We recommend starting supplementation with capsules containing pancreatic enzymes with the equivalent to 50,000 IU of lipase in each main meal and 25,000 IU for breakfast and snacks. In cases of total or partial pancreatectomy, severe pancreatic insufficiency or pancreatic cancer, the required doses may be higher.

SCD-SCPanc 12. Response to treatment should be evaluated by weight control, nutritional parameters, fat-soluble vitamins blood levels and assessment of symptoms, and not by monitoring faecal fat.

SCD-SCPanc 13. If response is suboptimal, we should consider increasing dosage of enzymes, inhibiting gastric acid secretion and ruling out bacterial overgrowth.

Normal lipase secretion at each main meal is about 90,000 IU. The total absence of pancreas induces frank steatorrhea, since less than 15% of lipase is produced outside the pancreas, and this amount of lipase is totally insufficient to digest the fat content of a balanced diet. The presence of steatorrhea due to EPI is a universally accepted reason for administering enzyme replacement therapy. If there is evidence of EPI documented by any of the diagnostic methods described in part 1 of this series, initiation of enzyme treatment is also indicated, but the grade of recommendation is lower.3,8

After pancreatic surgery, the presence of EPI can be difficult to demonstrate (arguments also explained in part 1 of this series) and it is considered sufficient to have a high degree of clinical suspicion to initiate enzyme treatment.23

If there is significant steatorrhea or obvious malnutrition, we can partially replace the lipid intake with easily absorbed medium chain triglycerides. But EPI without steatorrhea or evident malnutrition can be associated with deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins, magnesium, selenium, zinc, vitamin B12 and other microelements that we must normalize with appropriate treatment.24 Discussions about the indications for enzyme replacement therapy and whether or not to add nutritional supplements usually originate from economic reasons supported by macroscopic data (diarrhoea, weight, body mass index), ignoring the long-term harmful effects of a poor quality of absorption of nutrients and vitamins on various systems (osteoporosis, sarcopenia, neurological and cardiovascular disorders, etc.).

The administration of pancreatic enzymes reduces nutrient malabsorption, stabilizes body weight, improves symptoms and quality of life in patients with EPI and may have a positive impact on survival.25

Once the indication for enzyme replacement therapy has been established, the dose to be administered must be decided. The dose will depend on the clinical situation of each patient and the response obtained. In a patient with chronic pancreatitis and faecal elastase less than 50 µg/g of faeces, it is advisable to start treatment with 50,000 units of lipase during each main meal and 25,000 units at each secondary meal24,26,27 to provide at least 10% of the lipase needs at each meal.

We have to adapt the dosage to the dietary habits of the patient and the response should be evaluated with nutritional parameters.24 If it is not satisfactory, we can increase the dose of enzymes to even double the amount. Patients who tend to require greater enzyme intake are those who have severe pancreatic insufficiency and those who have undergone a pancreaticoduodenectomy in the presence of chronic pancreatitis.

To optimize the response, gastric acid secretion (which suppresses pancreatic enzyme activity) can be inhibited and a potential bacterial overgrowth can be treated. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is particularly frequent in some subgroups of patients with CrP,24 such as those who have undergone previous gastrointestinal surgery.26,27

Occasionally, nutritional supplementation may be necessary by mouth or through enteric feeding tubes.24

Chronic pancreatitis is usually a progressive disease, so enzyme requirements may increase over time or as a result of bouts of acute pancreatitis.

Despite administering a correct amount of pancreatic enzymes and achieving weight stability or weight gain, it is not uncommon to have to supplement patients with fat-soluble vitamins.24 We must monitor the plasma levels of these vitamins to act accordingly and be alert to the chronic pathology caused by vitamin deficiency (osteoporosis, dermatitis, neuropathy, etc.). We recommend a healthy diet rich in calcium, supplementing fat-soluble vitamins and deficient micronutrients, avoiding alcohol and tobacco, and exercising regularly.

Treatment of endocrine insufficiencySCD-SCPanc 14. The evolution of CrP usually leads to a profound decrease in the endocrine reserve and therefore secretagogue hypoglycaemic drugs are not very effective. The treatment of choice in most cases is insulin. Variable degrees of insulin resistance can coexist and in these cases metformin can be used. The correct use of pancreatic enzymes in the presence of exocrine insufficiency can help control the insulin response.

SCD-SCPanc 15. It is necessary to warn about the risk of hypoglycaemia induced by treatment and to instruct on its management.

The established paradigm of chronic pancreatitis as a progressive fibroinflammatory disease leads to imagine a process of inexorable destruction of the pancreatic islets that leads to the development of a marked deficiency of the endocrine stores. While this scenario is frequently true, it is not always the case. Often a component of peripheral insulin resistance can coexist, triggered by the underlying inflammatory events in the gland.

These arguments are important when planning treatment of diabetes mellitus in these patients. If there is concomitant insulin resistance, treatment with metformin can be initiated. And in these cases physical exercise can help.

Nutrient digestion and absorption may be important in stimulating incretin secretion (GIP and GLP-1) and postprandial insulin levels. Therefore, adequate treatment of exocrine insufficiency with pancreatic enzymes can have a favourable impact on endocrine insufficiency, as has been demonstrated in chronic pancreatitis associated with cystic fibrosis28.

There is little information on the risk-benefit of GLP1 or glucosuric analogues in the context of CrP, and therefore these drugs are not considered of any choice.

After some interventions (resolution of obstruction, alcohol withdrawal, corticosteroids in autoimmune pancreatitis), diabetes mellitus may improve.

If there is frank insulinopenia (low C-peptide in the presence of hyperglycaemia), the treatment of choice is insulin.29,30 Diabetes associated with CrP is usually more labile, with a higher risk of hypoglycaemia, due to concomitant glucagon deficiency. It is desirable that patients know how to prevent and correct hypoglycemia using rapid-acting carbohydrates, and that they have easy access to glucagon for intramuscular administration in cases of severe hypoglycaemia. The rational use of insulin by alcoholic patients must be mistrusted, a population in which the risk of hypoglycaemia is very high, both due to alcoholism and inadequate food intake.

Surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitisSCD-SCPanc 16. The primary indications for surgery are resolution of refractory pain, local complications, and suspicion of malignancy.

SCD-SCPanc 17. The complexity of these patients advocates for detailed evaluation in multidisciplinary committees of every single difficult case of CrP where conservative, endoscopic, interventional radiology or surgical therapeutic options are weighed.

SCD-SCPanc 18. Factors such as age, comorbidities, etiological factors (alcoholism, tobacco, genetics), development of exocrine and/or endocrine insufficiency, portal hypertension or other complications, or suspicion of neoplasia have an impact on the decision making process in view of selecting the therapeutic modality to administer and, if surgery is proposed, the type of intervention to perform.

Surgical efforts should be directed towards specific pathologies for which a clear benefit is anticipated, as in the case of the treatment of pancreatic pain, local complications or suspected malignancy.13 The mortality and morbidity associated with each type of intervention must always be taken into account. Asymptomatic CrP has no indications for surgery, nor does the new development of exocrine or endocrine insufficiency.

Some pathological conditions can be initially approached by endoscopy, such as biliary or duodenal stenosis. In the drainage of collections, all possible approaches (endoscopic, radiological and surgical) should be weighed in a multidisciplinary assessment and the one considered most appropriate should be implemented.

Morphology of the gland, the presence of calcifications, an inflammatory mass, ductal dilation or portal hypertension determines the selection of the surgical technique. If there is an inflammatory mass in the pancreatic head, a resection technique should be the first choice. Sometimes, combined procedures can be performed. The surgical approach to patients with portal hypertension should be tailored to the individual patient's situation. Severe bleeding may complicate any pancreatic resection. Therefore, derivative or mixed techniques are preferred, such as the Frey technique, in order to avoid risky resections of the pancreatic head. Advanced liver disease is a relative contraindication for pancreatic surgery, particularly if associated to portal cavernomatosis. Multidisciplinary committees in highly specialized centres should carefully evaluate indications of pancreatic surgery in high-risk patients.

Given the high risk of pancreatic cancer, prophylactic pancreatectomy has been proposed for patients with mutations in PRSS1.13

List of indications for surgery and types of procedures aimed at the underlying pathology:

- -

Pain refractory to medical treatment: derivative or resective techniques, or combination of both (already discussed at the pancreatic pain section above).

- -

Suspicion of pancreatic neoplasia: oncological resection surgery should be the first choice.

- -

Gastric or duodenal obstruction: gastroenteroanastomosis.

- -

Obstruction of the bile duct: hepatic-jejunostomy.

- -

Symptomatic pseudocyst: drainage methods to the digestive tract or resection (when located at the tail)

- -

Intractable pancreatic fistula: an individualized evaluation should be made.

- -

Haemorrhage due to portal hypertension secondary to splenic thrombosis: splenectomy with or without corporocaudal pancreatectomy.

We should be familiar with the most common post-surgical complications in order to identify them and treat them in time. They can develop during the perioperative stages or at any later time points.

Perioperative complications to bear in mind: External fistula (10–20%, more frequent in distal pancreatectomies), splenic injury and splenectomy, peripancreatic collections, abscesses, vascular lesions and generation of pseudoaneurysms, haemorrhage, venous thrombosis and embolisms, wound dehiscence and worsening of comorbidities.

Late complications31: delayed bleeding (due to pseudoaneurysm), chylous ascites, acute cholangitis, afferent loop syndrome, exocrine23 (30–49%) and endocrine (4–17%) pancreatic insufficiency, impaired gastric emptying (10%), bacterial overgrowth, postcibal asynchrony (functional EPI), pancreatic-enteric anastomosis stenosis (2–11%) with possible induction of postprandial pain and recurrent acute pancreatitis,32 ulcers and carcinoma in gastrojejunal anastomoses. Diabetes mellitus is more common after distal pancreatectomy than after cephalic duodenopancreatectomy (25% vs. 16%).33

Each of these complications requires a specific approach, the discussion of which is beyond the scope of this review. It is worth noting that some of these complications are difficult to resolve and pose a constant challenge to the pancreatologist, such as repeated acute cholangitis or the rare but disturbing recurrent acute pancreatitis due to pancreato-enteric junction stenosis. These later strictures can be resolved by balloon dilation, but the stenosed anastomosis often cannot be identified with the aid of an enteroscope. The alternatives are EUS-directed puncture of the dilated pancreatic duct with subsequent dilation of the stenosis and placement of a stent, or surgical intervention.

Quality of life, consumption of health resources and mortalitySCD-SCPanc 19. Chronic pancreatitis is associated with impaired quality of life and serious complications.

SCD-SCPanc 20. Chronic pancreatitis is also associated with a high incidence of comorbidities.

SCD-SCPanc 21. Mortality associated with chronic pancreatitis is disproportionately high.

SCD-SCPanc 22. Healthcare cost of patients with chronic pancreatitis is high.

SCD-SCPanc 23. Constitution of specialized multidisciplinary units of Pancreatology is mandatory.

CrP is a serious disease that has a strong impact on quality of life (QoL), which is particularly affected by pain and functional deterioration of the gland. It has also a clear propensity to produce long-term complications, some of which can be life-threatening34,35Up to 33% of patients will be on permanent sick leave.36 Patients who develop EPI after pancreatic surgery have a poorer quality of life.23

Several validated questionnaires can assess QoL in these patients (SF-36; SF-12; EORTC QLQ-C30, GIQLI, etc.). In clinical trials the most widely used are the QLQ-C30 and SF-36. None have been specifically designed for CrP.

Either due to the toxic habits of the patient, chronic nutritional deterioration or development of diabetes, patients with CrP have a predisposition to develop significant comorbidities during follow-up that can contribute to worsening QoL or even cause death. Among comorbidities most frequently associated with CrP are stroke, arterial disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, peptic ulcer, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, osteoporosis and neoplasms.37

Mortality in established chronic pancreatitis is 3.6 times higher than in the general population, with rates over 35% (55% at 20 years after initial diagnosis).38 Cancer is one of the frequent causes of death.38,39 Consumption of alcohol and tobacco also reduces survival. Alcohol consumption and smoking are responsible for 60–75% of deaths from extra-pancreatic causes, such as lung or oesophageal cancer, liver cirrhosis or myocardial infarction.34,37 Finally, the additive action of complications, comorbidities and diabetes further undermines the overall survival of these patients.3

The medical expenditure generated by patients with CrP is very high and it consumes large amounts of public resources. Hospital admissions are numerous and recurrent due to acute outbreaks and complications.40,41 The expenses per hospital admission are increasingly higher,35 with readmission rates of 30% at 30 days (half of them related to pancreatic disease41–43).

To all this spending it should be added the costs for loss of endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function, and for pain management. An estimate of direct and indirect costs would be €88,613 per patient/year.40

CrP patients need a multidisciplinary health and social approach. A comprehensive coordination between different health professionals is needed in order to optimize resources, guarantee adherence to treatments and achieve efficient surveillance protocols aimed at anticipating and avoiding complications of the disease. Therefore, the constitution of specialized multidisciplinary units of pancreatology is mandatory. With the complicity of the assigned professionals the goals of these units should be to provide a better comprehensive medical care, reduce the rate of complications, improve the quality of life of these patients, reduce the associated mortality and optimize health care resources.

Follow-up of patients with chronic pancreatitisSCD-SCPanc 24. In patients with stable disease, we recommend carrying out clinical and analytical controls every 6–12 months. We should raise concern on patients who present a change in the pattern of pain, weight loss and/or jaundice. If complications appear, follow-up must be individualized.

SCD-SCPanc 25. The nutritional status of the patients must be assessed at regular intervals and the dose of pancreatic enzymes or vitamin supplements should be adjusted if necessary.

The goal of follow-up is to detect the development of endocrine failure, exocrine failure, or complications. It is not well established how often medical check ups should be scheduled. A judicious rule would be to carry out clinical and laboratory controls every 6 or 12 months in patients with stable disease.24 Blood tests should include nutritional parameters, fat-soluble vitamins, micronutrients, vitamin B12, folic acid, ferritin and glycated haemoglobin.24 It is also wise to determine faecal elastase every 24 months if there was no previous EPI, or if there is nutritional deterioration, weight loss, or new bouts of acute pancreatitis have occurred.

In the event of symptoms or suspected complications, we should request imaging tests. In patients who already present complications follow-up must be individualized and will accommodate to the type and severity of the complications (see part 3 of this series).

It is important to assess the nutritional status of the patient, including measurements of body mass index and sarcopenia.24 Also check whether vitamin supplements are needed and make dietary recommendations. We have to check that the patient comply with the prescribed treatment, in particular pancreatic enzyme supplementation dosage. In case of suboptimal results, it is time to consider increasing the dose or introducing some other therapeutic amendment.

A baseline bone densitometry should always be performed, and every two years if osteopenia is detected.36

The clinical course is unpredictable. There is no model to assess disease severity, progression, or prediction of treatment outcomes. Cessation in alcohol and tobacco consumption reduces attacks of pancreatitis, chronic pain, progression of the disease, risk of complications, risk of cancer, and increases life expectancy.44

Early diagnosis of pancreal cancerSCD-SCPanc 26. If an indication for screening and surveillance of pancreatic cancer is established, we recommend performing EUS and MRI in the initial screening and leaving MRI for follow-up, indicating EUS-directed fine needle aspiration or biopsy if doubtful lesions appear. Screening and surveillance should be carried out in specialized centres.

Screening and surveillance of pancreatic cancer in CrP patients is controversial and we have not reached a satisfactory consensus position. The risk of developing pancreatic cancer in patients with CrP is believed to be 2% at 10 years and 4% at 20 years of follow-up. It is quite likely the risk would be higher if we only take into account those patients with a definitive diagnosis of CrP, or those with specific etiological factors such as genetic mutations.45

Currently various groups of experts recommend screening and surveillance for pancreatic cancer only in cases of hereditary pancreatitis,46 initiating investigations from the age of 40–45 years (or 15 years before the youngest case of cancer in the family) with surveillance at intervals of 1–3 years.

In the rest of patients, a number of medical societies do not recommend any screening or surveillance. It is worth noting, however, that the risk of developing cancer in CrP ranges between ×2 and ×15 (even ×27)47 and it turns out that several study committees propose screening programs for other pancreatic conditions with associated cancer risks as low as ×5 or ×1048,49. This risk increases with age, it is higher in patients with recent diagnosis of CrP or diabetes, smokers, and carriers of genetic mutations.47

We also did not meet any consensus position on which is the best tests to perform to rule out neoplasia in the context of chronic pancreatitis, since small lesions are difficult to identify with the imaging tests available on a CrP background. It would be very helpful to have sensitive and specific serological markers at hand, a condition that CA 19.9 does not fully meet.

Financial supportWe have not received any kind of financial support for the preparation of the present document.

Conflict of interestXavier Molero is consultant investigator for Amadix Advanced Marker Discovery S.L (Acera de Recoletos 2, 1B, 47004 Valladolid) in the research project on pancreatic cancer AMD-CPA-2016-01

Xavier Molero has obtained a research grant on fundamental investigation on cystic fibrosis in mice from Vertex Pharmaceutical Inc., 50 Northern Avenue, Boston, MA 02210, USA.

None of the other above authors declares any other conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Molero X, Ayuso JR, Balsells J, Boadas J, Busquets J, Casteràs A, et al. Pancreatitis crónica para el clínico. Parte 2: Tratamiento y seguimiento. Documento de posicionamiento interdisciplinar de la Societat Catalana de Digestologia y la Societat Catalana de Pàncrees. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;45:304–314.