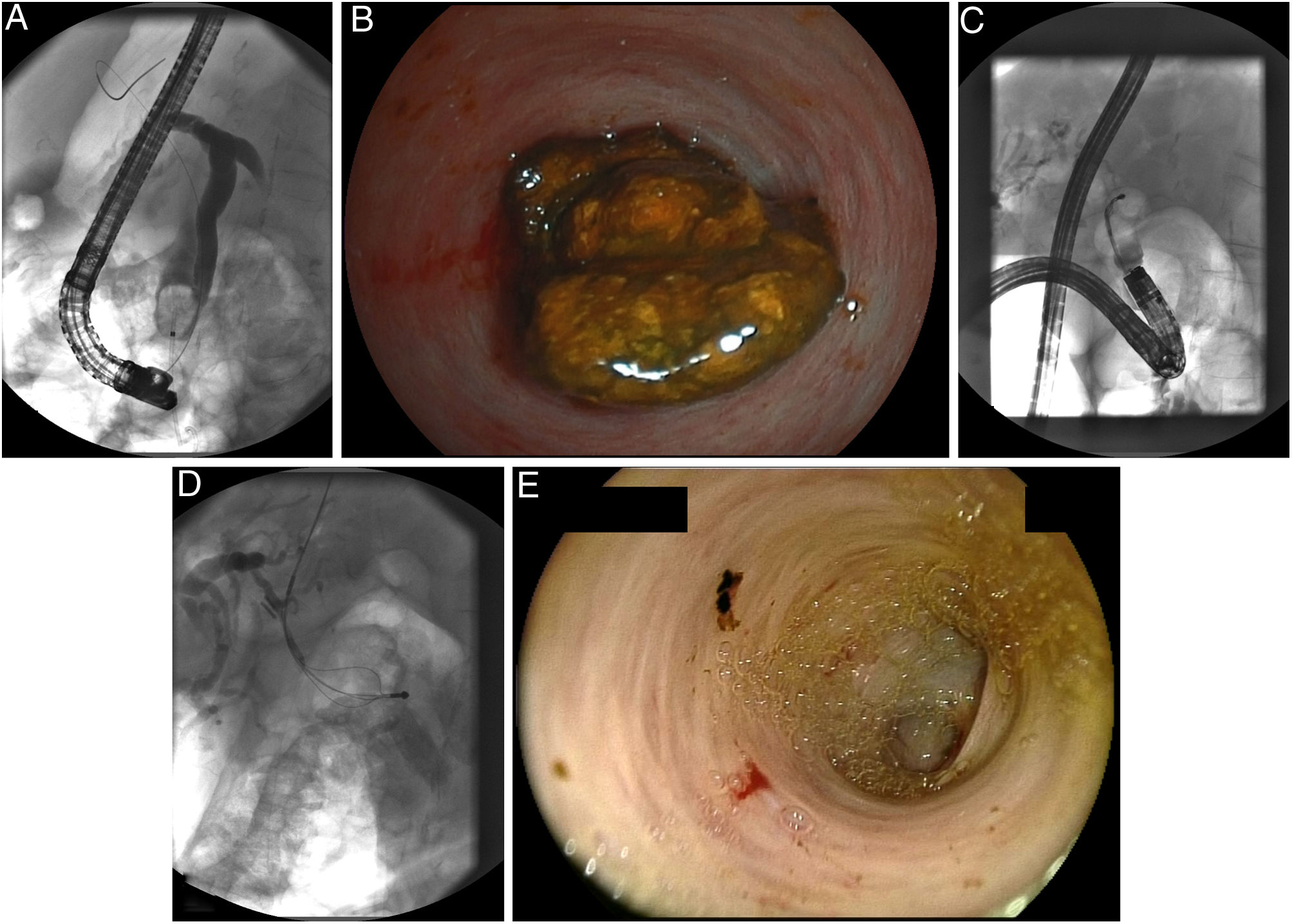

An 85-year-old female underwent urgent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) under piperacillin/tazobactam due to acute bacterial cholangitis. Biliary access was achieved after transpancreatic sphincterotomy and prophylactic 5-Fr pancreatic single pigtail stenting. On (limited) cholangiogram an estimated 30-mm common bile duct (CBD) stone at the branch-off of a low-inserting cystic duct (CD) come to our notion. (Fig. 1A) Biliary 10-Fr plastic stenting was performed after standard-incision papillotomy to ensure biliary drainage, and repeat ERCP was scheduled with intention to perform endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation (EPLBD) to assist in stone extraction. This was accomplished up to 15mm using a controlled radial expansion balloon without difficulties taking care to limit introduction of the device into the CBD, so as to avoid inflation alongside the large stone and diverticulum formation.1 However, since the stone was not to be mobilized by a large-size ERCP balloon nor be captured in a Dormia basket, we performed freehand-intubated direct cholangioscopy (DC) using a standard size gastroscope (outer diameter 9.8mm; working channel 2.8mm) to fully visualize the nearly lumen-occluding giant stone. (Fig. 1B) Basket capture under coordinated endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 1C) finally succeeded using a rotable basket with high expansion forces (twist’n’CATCH, Medwork, Höchstadt/Aich, Germany), and mechanical lithotripsy (ML) was performed without complications using an emergency lithotriptor device. (Fig. 1D) Following this, additional ML fragments were retrieved from the biliary system by standard ERCP technology. A final repeat DC up to the hilum firmly excluded remant stone disease in the diffusely dilated biliary system with ample pneumobilia after large-bore EPLBD further reducing the informativeness of pure cholangiography.2

(A) An estimated 30-mm large distal common bile duct (CBD) stone – note limited cholangiogram due to acute cholangitis. Note also contrast media mostly flowing into the cystic duct (CD) reflective of the sub-occlusive nature of this “giant” stone. (B) Direct cholangioscopy (DC) using a standard gastroscope likewise exposes the lumen-occlusive stone, and (C) co-ordinated movements under endoscopic and fluoroscopic control resulted in successful basket capture (35-mm rotable device with high expansion forces). (D) This was followed by an uncomplicated mechanical lithotripsy (ML) using an emergency lithotriptor device. (E) After conventional ERCP-based extraction of ML fragments repeat DC up to the hilum firmly excluded remnant stone material in the diffusely dilated biliary system.

DC-guided ML has rarely been reported, mostly because cholangioscopy-based stone management is dominated by electrohydraulic (EHL) and/or laser lithotripsy (LL) techniques considered more elegant and powerful in such setting.3 Notwithstanding, in this unique case catheter-based lithotripsy had not been planned beforehand. To conclude, cholangioscopy-guided ML using standard size upper endoscopes with a working channel with adequate diameter to accommodate ERCP equipment may represent another viable option, when ERCP-based Dormia basket capture as a sine qua non for ML fails.

Potential conflict of interestNothing to declare.