There is evidence that following the recommendations on screening and treatment of tuberculosis infection does not completely prevent the onset of tuberculosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. This fact, and the increasing use of new biologics and immunomodulators, has led the Spanish Group Working on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis to update their recommendations for the prevention of tuberculosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Diagnostic methods for latent tuberculosis infection, different scenarios in which screening is to be performed, strategies to reduce the risk of tuberculosis once biological treatment is initiated and chemoprophylaxis guidelines for latent tuberculosis infection are reviewed, as well as the management of active tuberculosis during biological treatment. Finally, there is a summary of the current recommendations within the paper and in an algorithm.

La evidencia de que el seguimiento de las recomendaciones sobre el cribado y tratamiento de la infección tuberculosa no evita totalmente la aparición de tuberculosis en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal, y el uso reciente de nuevos fármacos biológicos y de nuevos inmunomoduladores, ha llevado al Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y en Colitis Ulcerosa a actualizar sus recomendaciones para la prevención de la tuberculosis en los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Se revisan los métodos de diagnóstico de la infección tuberculosa latente, los distintos escenarios en los que se va a realizar el cribado, las estrategias para disminuir el riesgo de tuberculosis una vez iniciado el tratamiento biológico, las pautas de quimioprofilaxis de la infección tuberculosa latente y el manejo de la tuberculosis activa durante el tratamiento biológico. Finalmente, se resumen las recomendaciones en el texto y con un algoritmo.

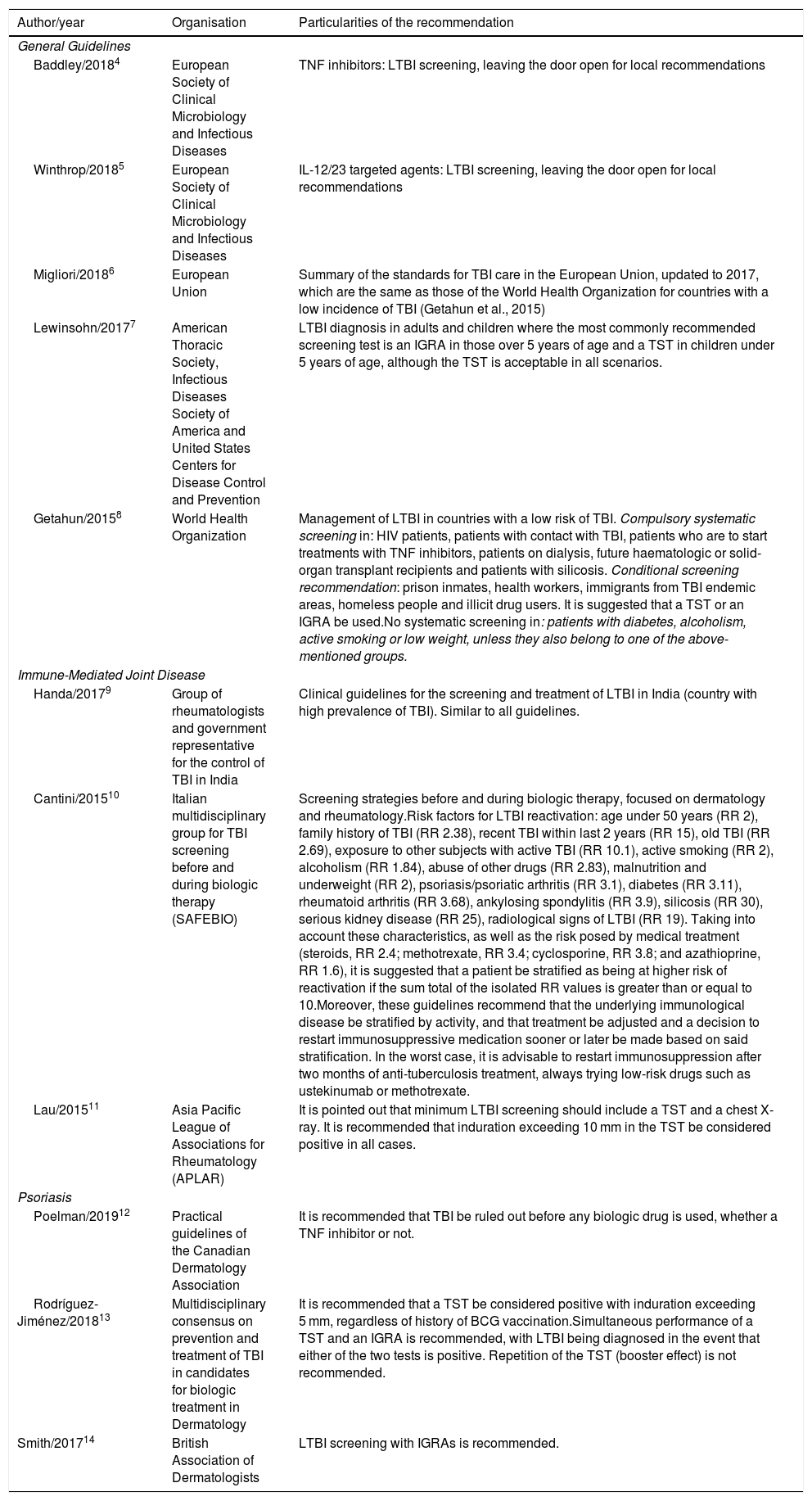

There is a known risk of developing active tuberculosis (TB) during treatment with tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha inhibitors.1 To try to minimise this risk, different scientific associations have published clinical guidelines and recommendations. In 2003, the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] (GETECCU) published its first recommendations for the screening and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).2 These were last updated in 2015.3 In the last five years, guidelines have been published for the diagnosis and treatment of LTBI in patients with joint and dermatological disease who are to receive treatment with TNF inhibitors and other biologics. Table 1 shows a summary of these guidelines, as well as some of their particularities.4–14 There is a great deal of variability in the recommendations, due in part to the fact that they take into account local socioeconomic conditions, the prevalence of LTBI, local treatment practices4 and the variable risk of TB associated with the underlying immune-mediated disease.10

Guidelines on the study, prevention and management of tuberculosis infection in the last 5 years, excluding those for IBD.

| Author/year | Organisation | Particularities of the recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| General Guidelines | ||

| Baddley/20184 | European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases | TNF inhibitors: LTBI screening, leaving the door open for local recommendations |

| Winthrop/20185 | European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases | IL-12/23 targeted agents: LTBI screening, leaving the door open for local recommendations |

| Migliori/20186 | European Union | Summary of the standards for TBI care in the European Union, updated to 2017, which are the same as those of the World Health Organization for countries with a low incidence of TBI (Getahun et al., 2015) |

| Lewinsohn/20177 | American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America and United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | LTBI diagnosis in adults and children where the most commonly recommended screening test is an IGRA in those over 5 years of age and a TST in children under 5 years of age, although the TST is acceptable in all scenarios. |

| Getahun/20158 | World Health Organization | Management of LTBI in countries with a low risk of TBI. Compulsory systematic screening in: HIV patients, patients with contact with TBI, patients who are to start treatments with TNF inhibitors, patients on dialysis, future haematologic or solid-organ transplant recipients and patients with silicosis. Conditional screening recommendation: prison inmates, health workers, immigrants from TBI endemic areas, homeless people and illicit drug users. It is suggested that a TST or an IGRA be used.No systematic screening in: patients with diabetes, alcoholism, active smoking or low weight, unless they also belong to one of the above-mentioned groups. |

| Immune-Mediated Joint Disease | ||

| Handa/20179 | Group of rheumatologists and government representative for the control of TBI in India | Clinical guidelines for the screening and treatment of LTBI in India (country with high prevalence of TBI). Similar to all guidelines. |

| Cantini/201510 | Italian multidisciplinary group for TBI screening before and during biologic therapy (SAFEBIO) | Screening strategies before and during biologic therapy, focused on dermatology and rheumatology.Risk factors for LTBI reactivation: age under 50 years (RR 2), family history of TBI (RR 2.38), recent TBI within last 2 years (RR 15), old TBI (RR 2.69), exposure to other subjects with active TBI (RR 10.1), active smoking (RR 2), alcoholism (RR 1.84), abuse of other drugs (RR 2.83), malnutrition and underweight (RR 2), psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (RR 3.1), diabetes (RR 3.11), rheumatoid arthritis (RR 3.68), ankylosing spondylitis (RR 3.9), silicosis (RR 30), serious kidney disease (RR 25), radiological signs of LTBI (RR 19). Taking into account these characteristics, as well as the risk posed by medical treatment (steroids, RR 2.4; methotrexate, RR 3.4; cyclosporine, RR 3.8; and azathioprine, RR 1.6), it is suggested that a patient be stratified as being at higher risk of reactivation if the sum total of the isolated RR values is greater than or equal to 10.Moreover, these guidelines recommend that the underlying immunological disease be stratified by activity, and that treatment be adjusted and a decision to restart immunosuppressive medication sooner or later be made based on said stratification. In the worst case, it is advisable to restart immunosuppression after two months of anti-tuberculosis treatment, always trying low-risk drugs such as ustekinumab or methotrexate. |

| Lau/201511 | Asia Pacific League of Associations for Rheumatology (APLAR) | It is pointed out that minimum LTBI screening should include a TST and a chest X-ray. It is recommended that induration exceeding 10 mm in the TST be considered positive in all cases. |

| Psoriasis | ||

| Poelman/201912 | Practical guidelines of the Canadian Dermatology Association | It is recommended that TBI be ruled out before any biologic drug is used, whether a TNF inhibitor or not. |

| Rodríguez-Jiménez/201813 | Multidisciplinary consensus on prevention and treatment of TBI in candidates for biologic treatment in Dermatology | It is recommended that a TST be considered positive with induration exceeding 5 mm, regardless of history of BCG vaccination.Simultaneous performance of a TST and an IGRA is recommended, with LTBI being diagnosed in the event that either of the two tests is positive. Repetition of the TST (booster effect) is not recommended. |

| Smith/201714 | British Association of Dermatologists | LTBI screening with IGRAs is recommended. |

BCG: Bacillus Calmette–Guerin; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IGRA: interferon-gamma release assay; LTBI: latent tuberculosis infection; TBI: tuberculosis infection; TNF: tumour necrosis factor; TST: tuberculin skin test.

The evidence that following the recommendations does not entirely prevent the development of TB in patients with IBD, as well as the publication of new data on TB screening and monitoring and the recent use of new biologic drugs and new immunomodulators (IMMs), has led the GETECCU to update its recommendations for the prevention of TB in patients with IBD.

Epidemiology of tuberculosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseSome 50%-70% of people infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) clear the infection through innate or adaptive immunity. The rest develop LTBI (95%) or early active disease (5%). In the course of their lives, 5%-15% of patients with LTBI will reactivate the infection and develop active disease.15,16

In 2017, 4571 cases of active TB were reported in Spain, which represents an incidence of 9.43 cases/100,000 inhabitants/year and places the country as an area of low incidence (<10 cases/100,000 inhabitants/year). However, there are significant differences between autonomous communities, some with rates of >10 cases/100,000/year (Galicia 19.56; Catalonia 12.93; Basque Country 10.47; Aragon 10.18) and others with rates of <6 cases/100,000 (Canary Islands 5.13; Extremadura 5.12; Navarra 4.06).17 Meanwhile, the prevalence of LTBI in patients with IBD remains high (12.5%-33.5%),18,19 meaning that there is a large number of patients at risk of reactivation of the infection.

Treatment with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants and TNF inhibitors increases the risk of developing active TB.20 This risk is even higher when multiple such drugs are combined.21 In Spain, 94% of cases of TB in patients with IBD occur during treatment with TNF inhibitors.22 TB cases have also been reported during treatment with biologic drugs with different mechanisms of action, such as anti-IL-12/23 (ustekinumab) and anti-integrins (vedolizumab), although the risk appears to be lower than with TNF inhibitors.23,24 Tofacitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, is capable of increasing M. tuberculosis replication in experimental mouse models with LTBI.25 Furthermore, TB is the most common opportunistic infection in tofacitinib approval trials in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, especially in areas with a high incidence of TB.26 Currently, the LTBI screening recommended before starting treatment with TNF inhibitors has been incorporated into the technical data sheet for new biologics and IMMs. Moreover, patients with IBD are also at risk of primary M. tuberculosis infection due to nosocomial transmission27,28 or following stays in geographic areas with a high incidence of TB.29 All of the above factors contribute to IBD patients having a higher risk of active TB than the general population. On the one hand, immunosuppressant and biologic drugs increase the risk of reactivation of LTBI; on the other hand, they would increase the risk of early active TB occurring after primary M. tuberculosis infection. There is a need for molecular epidemiology studies that genotype M. tuberculosis and thus indicate which TB episodes are a reactivation of an LTBI (if a strain with an orphan or unique pattern is isolated) or a de novo infection (if a strain with a pattern similar to that of other circulating strains is isolated).

Diagnostic methods for latent tuberculosis infectionThere is no gold standard diagnostic technique. Traditionally, the diagnostic process includes a medical history, a chest X-ray and immunodiagnostic tests.

- 1

The medical history is aimed at detecting risk factors for exposure to M. tuberculosis. Certain people are at higher risk of presenting LTBI: those who have had contact with patients with active TB; those who originate from or have travelled to countries with a high incidence of TB; health personnel; residents of and workers at closed establishments (prisons, shelters and other social institutions); drug users; and those in states of immunosuppression such as human immunodeficiency virus infection; transplant recipients; and those with other comorbidities such as tumours, silicosis and chronic kidney failure on haemodialysis.8 In the event that the screening is negative, preventive treatment for LTBI reactivation should be performed, only if there has been recent, close and continuous contact with a smear-positive patient. Preventive treatment should also be administered if there is epidemiological evidence of improperly treated previous TB.3

- 2

Some guidelines recommend taking a chest X-ray to look for signs of previous TB (calcified nodes or nodules, pleural apical thickening and/or fibrous tracts),11–14 while according to others, a chest X-ray would be done only to rule out active TB following a positive immunodiagnostic test or in the event of recent contact with somebody with TB.7,9,10 Performing a chest X-ray in a protocolised manner does not appear to increase the ability to detect LTBI provided by the combination of a tuberculin skin test (TST) and an interferon gamma release assay (IGRA). It also remains unclear what type of lesion on X-ray is associated with a risk of reactivation of LTBI.30 For these reasons, some of the most recent guidelines (Table 1) exclude this test and call for performing it only when an initial positive screening with a TST or an IGRA is positive (or both are). Chest computed tomography is more sensitive than plain X-ray to detect any type of lesion, but its systematic use would not be indicated given the high cost and risk of radiation weighed against the low increase in diagnosis.31 For all of the above reasons, chest X-ray would only be recommended in cases of positive screening or in the event of recent contact with somebody with tuberculosis, to rule out an active infection.

- 3

Immunodiagnostic tests: both the TST and the IGRA detect the immune response of memory T cells against M. tuberculosis antigens, without being able to distinguish an LTBI from an active infection.

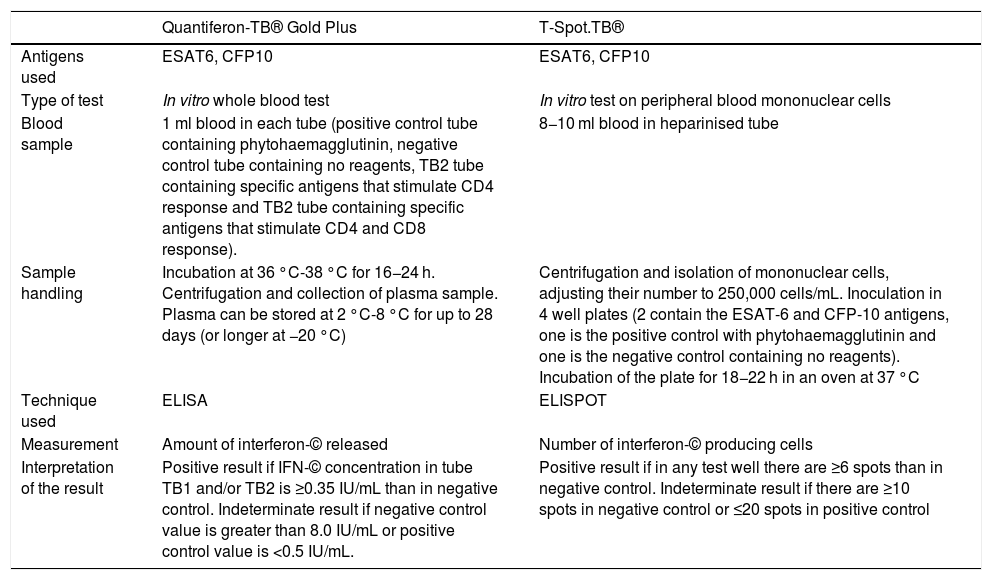

The TST detects, in vivo, a delayed cellular hypersensitivity to purified protein derivative (PPD), which contains more than 200 proteins from M. tuberculosis, some of which are also present in BCG and certain environmental mycobacteria. IGRAs enable measurement, in vitro, of interferon-gamma (IFN-©) production by T lymphocytes sensitised to M. tuberculosis. The antigens used to stimulate the immune response (ESAT-6, CFP-10) are encoded by genes located in the region of difference 1 (RD1) of M. tuberculosis, and are not present in the BCG vaccine or in most environmental mycobacteria.32 There are currently two IGRAs on the market: the QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus® (QFT-Plus) (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany) and the T-SPOT.TB® (T-SPOT) (Oxford Immunotec, Oxford, United Kingdom). Table 2 summarises their characteristics.

Technical characteristics and interpretation of the results of the interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) on the market.

| Quantiferon-TB® Gold Plus | T-Spot.TB® | |

|---|---|---|

| Antigens used | ESAT6, CFP10 | ESAT6, CFP10 |

| Type of test | In vitro whole blood test | In vitro test on peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| Blood sample | 1 ml blood in each tube (positive control tube containing phytohaemagglutinin, negative control tube containing no reagents, TB2 tube containing specific antigens that stimulate CD4 response and TB2 tube containing specific antigens that stimulate CD4 and CD8 response). | 8−10 ml blood in heparinised tube |

| Sample handling | Incubation at 36 °C-38 °C for 16−24 h. Centrifugation and collection of plasma sample. Plasma can be stored at 2 °C-8 °C for up to 28 days (or longer at −20 °C) | Centrifugation and isolation of mononuclear cells, adjusting their number to 250,000 cells/mL. Inoculation in 4 well plates (2 contain the ESAT-6 and CFP-10 antigens, one is the positive control with phytohaemagglutinin and one is the negative control containing no reagents). Incubation of the plate for 18−22 h in an oven at 37 °C |

| Technique used | ELISA | ELISPOT |

| Measurement | Amount of interferon-© released | Number of interferon-© producing cells |

| Interpretation of the result | Positive result if IFN-© concentration in tube TB1 and/or TB2 is ≥0.35 IU/mL than in negative control. Indeterminate result if negative control value is greater than 8.0 IU/mL or positive control value is <0.5 IU/mL. | Positive result if in any test well there are ≥6 spots than in negative control. Indeterminate result if there are ≥10 spots in negative control or ≤20 spots in positive control |

In clinical practice, several questions arise with regard to the usefulness of immunodiagnostic tests in the diagnosis of LTBI:

- •

Should BCG vaccination history be taken into account in interpreting the TST result?

The specificity of the TST for the diagnosis of LTBI is reduced by the presence of environmental mycobacteria and by BCG vaccination.33 Nevertheless, those vaccinated at birth rarely have a false positive result after 10 years, whereas the rate of false positives if vaccination occurs after the first year of life is 20%.34 In Spain, BCG vaccination was compulsory at birth between 1965 and 1981, and only in the Basque Country did vaccination continue until January 2013. Hence, its influence on TST results may not be significant. In the immigrant population from countries where BCG vaccination is still compulsory, the specificity of the TST could be compromised,33 although it has been shown that, in subjects over 30 years of age, the influence of vaccination is minimal, regardless of age at vaccination or revaccination.35 Our recommendation, in line with recent guidelines from the United States and Europe, is to perform the TST without taking BCG vaccination status into account, in both paediatric and adult patients.13,36

- •

What is the risk of a false negative TST result in patients receiving corticosteroids and/or IMMs?

The sensitivity of the TST is influenced by states of immunosuppression and by problems inherent in the test itself (failures in tuberculin storage or dilution, improper injection, errors in reading). Patients with IBD, probably due to immunosuppression, but also due to a deficient Th1 response,37 present a phenomenon of anergy38 that would limit the usefulness of the TST in this context. In a recent meta-analysis, immunosuppressive treatment was significantly associated with a lower percentage of TST positivity (OR 0.51; 95% CI 0.42−0.61).39

- •

Is it useful to administer a booster in the TST?

In patients with IBD, performing a second TST 7–10 days after the first negative TST enables diagnosis of 5.5%-25% more patients with LTBI.18,19,40 These positive conversions are due to the so-called booster effect on the immune response of a second injection of PPD in subjects previously infected with M. tuberculosis (although it could also appear, to a lesser extent, in subjects vaccinated with BCG).41 A limitation of performing a second TST is the high number of visits (four) made by the patient to the health centre, which may explain why it is the main cause of non-compliance with the screening recommendations in Spain.42

- •

How should indeterminate results in an IGRA be interpreted?

The main advantages of the IGRA compared to the TST are the absence of interference with the BCG vaccine, the objectivity in the interpretation of the results, the existence of positive and negative controls and the lack of need for a second test-reading visit. However, a limitation is that some results are indeterminate. This happens when there is a high level of IFN-© in the negative control or a low level in the positive control, and it prevents confirmation or ruling out of a diagnosis of TB infection. Most indeterminate results are caused by a lack of response in the positive control of the test (tube with mitogen),43 and have been associated with hypoalbuminaemia and immunosuppressive treatment, especially corticosteroid use.19,44 The few studies that have analysed both IGRAs in IBD patients have shown a higher percentage of indeterminate results with T-SPOT (6%-25%) than with QFT-GIT (2.4%-10%).19,45,46 In a patient with an indeterminate result on a QFT-GIT test, if the test is repeated before the lapse of six months, the result will be negative in 61% of cases and indeterminate again in 28%.43

- •

What is the risk of a false negative IGRA result in patients receiving treatment with immunosuppressants or biologics?

A meta-analysis found that the use of immunosuppressive drugs (corticosteroids and IMMs) reduces the percentage of QFT-GIT positivity, while it did not demonstrate an effect on T-SPOT results, though the statistical power of the analysis was low as few studies were included.39 What has been observed is that, when adding the IGRAs to the TST in patients with IBD on immunosuppressive treatment, the number of patients diagnosed with LTBI increases, with the improvement in diagnosis being greater with the T-SPOT (56%) than with the QFT-GIT (22%).19 IGRA results may also be affected in patients treated with TNF inhibitors. The above-mentioned meta-analysis found that patients treated with a TNF inhibitor had a 50% reduction in their likelihood of a positive IGRA.39 This is probably because TNF inhibitors decrease the number of CD4-T lymphocytes that produce IFN-©.47

- •

Does performing a TST influence the result of an IGRA?

After performing a TST, there is a boost in IFN-© production that can alter IGRA results. This occurs when IGRAs are performed more than three days after the PPD injection, and usually disappears after three months.48 Although this effect is seen particularly in subjects who were already IGRA-positive, it has also been observed in IGRA-negative subjects, especially with QFT.49 Therefore, it is recommended that IGRAs be done simultaneously with the PPD injection, or no later than three days after it.

- •

How should fluctuations and borderline results for an IGRA be interpreted?

When an IGRA is performed serially on the same patient, fluctuations in IFN-© concentrations are observed;48 this represents a limitation for its use in monitoring TB infection. These variations have been linked to variability in the laboratory technique and, in some cases, to a weak immune response against M. tuberculosis. As a result, an area of uncertainty has been established for QFT results between 0.20 and 0.70 IU/mL, and true converters are defined as subjects in whom the IFN-© value increases from <20 to >70 IU/mL.50

- •

Are there differences between the TST and IGRAs in their ability to detect old TB?

Following properly treated active TB, IGRAs often become negative, contrary to what happens with the TST.51 Therefore, IGRAs would detect a lower number of old infections than the TST, because the IFN-© level would not increase during the 16 h of exposure to the antigen in the IGRAs, but would increase after the 72 h of exposure in the TST. It has been shown that the prolonged incubation in IGRAs could also detect some remote infections not detected with normal incubation.52

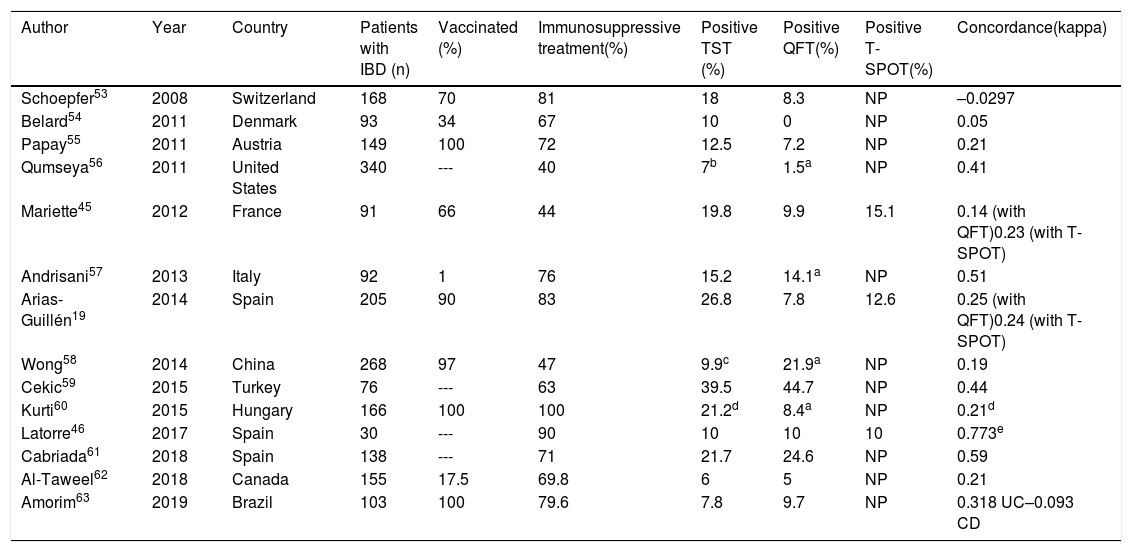

Table 3 shows the main results of the studies that have jointly used the TST and an IGRA for LTBI screening in patients with IBD. Concordance between TST and IGRA results is low. Some of the above-mentioned limitations of the immunodiagnostic tests may account for this low concordance (possible influence of BCG vaccination, differing ability to detect old infections and variable impact of immunosuppression and biologic therapy on each test). In certain scenarios, such as immunosuppression, the two types of test are considered complementary to each other.

Results of latent tuberculosis infection screening studies using the tuberculin test and an IGRA (dual screening) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Author | Year | Country | Patients with IBD (n) | Vaccinated (%) | Immunosuppressive treatment(%) | Positive TST (%) | Positive QFT(%) | Positive T-SPOT(%) | Concordance(kappa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schoepfer53 | 2008 | Switzerland | 168 | 70 | 81 | 18 | 8.3 | NP | –0.0297 |

| Belard54 | 2011 | Denmark | 93 | 34 | 67 | 10 | 0 | NP | 0.05 |

| Papay55 | 2011 | Austria | 149 | 100 | 72 | 12.5 | 7.2 | NP | 0.21 |

| Qumseya56 | 2011 | United States | 340 | --- | 40 | 7b | 1.5a | NP | 0.41 |

| Mariette45 | 2012 | France | 91 | 66 | 44 | 19.8 | 9.9 | 15.1 | 0.14 (with QFT)0.23 (with T-SPOT) |

| Andrisani57 | 2013 | Italy | 92 | 1 | 76 | 15.2 | 14.1a | NP | 0.51 |

| Arias-Guillén19 | 2014 | Spain | 205 | 90 | 83 | 26.8 | 7.8 | 12.6 | 0.25 (with QFT)0.24 (with T-SPOT) |

| Wong58 | 2014 | China | 268 | 97 | 47 | 9.9c | 21.9a | NP | 0.19 |

| Cekic59 | 2015 | Turkey | 76 | --- | 63 | 39.5 | 44.7 | NP | 0.44 |

| Kurti60 | 2015 | Hungary | 166 | 100 | 100 | 21.2d | 8.4a | NP | 0.21d |

| Latorre46 | 2017 | Spain | 30 | --- | 90 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0.773e |

| Cabriada61 | 2018 | Spain | 138 | --- | 71 | 21.7 | 24.6 | NP | 0.59 |

| Al-Taweel62 | 2018 | Canada | 155 | 17.5 | 69.8 | 6 | 5 | NP | 0.21 |

| Amorim63 | 2019 | Brazil | 103 | 100 | 79.6 | 7.8 | 9.7 | NP | 0.318 UC–0.093 CD |

CD: Crohn's disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IGRA: interferon gamma release assay; NP: not performed; QFT: quantiferon; TST: tuberculin skin test; UC: ulcerative colitis.

- 1

Should early LTBI screening be performed in all patients with IBD?

Early screening is understood as screening performed when there is still no indication for biologic therapy.40 Ideally, it should be performed when IBD is diagnosed, before the patient receives immunosuppression (or up to two weeks after starting immunosuppression) or, failing that, following treatment of the first flare-up (three weeks after stopping corticosteroids),29 preferably with a low inflammatory load. At diagnosis, there is often a high inflammatory load that precludes early screening; in these cases, it must be done in any subsequent period during which the patient is in a situation of immunocompetence. Early screening for LTBI is recommended in all patients with IBD since, potentially, all of them could require treatment with biologic agents. The SEGURTB study found that the probability of a positive result from an early TST (performed prior to any indication for biologic therapy but not necessarily at diagnosis), without associated immunosuppression and with a low inflammatory load, was double compared to the compulsory TST performed before starting a TNF inhibitor.40 However, the cost/benefit ratio of this screening strategy for IBD diagnosis in all patients could vary depending on the prevalence of LTBI in the general population.

In situations of immunocompetence, especially in the group of patients without risk factors for LTBI, several scientific associations recommend performing a single screening test.7,11,12 In Spain, TST would be preferable to IGRA for the following reasons: 1) BCG vaccination in the country has practically no influence on the TST result, 2) TST is a cheap test and 3) TST can detect older infections than IGRAs can. In this context, a second TST (booster) would not be necessary. Nevertheless, performing an IGRA as a single test, though less sensitive for detecting old cases, could also be a valid strategy.8,64

In the case of a positive early screening test, it is advisable to delay chemoprophylaxis until the patient receives biologic treatment.40 It is necessary to avoid overtreatment with isoniazid of patients who will not require biologic treatment. Moreover, early chemoprophylaxis would not protect against further contact with M. tuberculosis occurring in the interval between the positive early test and the start of biologic therapy. It is compulsory to explain this recommendation to the patient, bearing in mind that, although administering chemoprophylaxis in the event of a positive early screening is not improper, it does not appear to be justified from an epidemiological point of view.

- 2

How much time must elapse following a negative screening for it to be repeated before starting biologic treatment?

The most significant predictor of LTBI reactivation in patients receiving treatment with TNF inhibitors is the absence of suitable recent screening.42,65 There is no evidence to support the notion that a patient who has had a negative screening should repeat it systematically before starting biologic treatment, despite the fact that it is a recommended practice.10,64 Given this, we believe that compulsory screening should be repeated before starting biologic therapy in all patients if more than 12 months have elapsed since the previous screening, or earlier if it was not performed in a situation of immunocompetence or if risk factors for tuberculosis infection (contact, travel or occupational risk) are present.

- 3

What screening is compulsory before starting biologic or JAK inhibitor therapy?

Compulsory screening is understood as screening performed when there is an indication for biologic or JAK-inhibitor therapy. Usually, patients who are to receive biologic therapy are immunosuppressed, both due to the use of drugs (corticosteroids and IMMs) and to active inflammation and malnutrition. This considerably reduces the sensitivity of the screening tests for LTBI. In this scenario, in both patients without previous screening and patients with negative previous screening, compulsory dual screening with TST and IGRA62 should be performed immediately before the use of biologics. Dual screening increases the diagnostic capacity of LTBI, has been studied in patients with IBD19 and rheumatic diseases,66,67 and is recommended by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)36 and other scientific associations.13,65,68 Patients with a positive result for either of the two tests should receive LTBI chemoprophylaxis. It is also suggested that this dual screening strategy be used in people in areas with a medium to high prevalence of TB and in patients with additional risk factors for LTBI.64 In situations of immunosuppression and scenarios in which IGRA is not available, it is recommended that a second TST (booster) be added 7–10 days after a first negative TST.

Strategies to reduce the risk of tuberculosis after starting biologic treatmentPatients with IBD who are receiving biologic treatment are at higher risk of developing active TB, both due to reactivation of LTBI undiagnosed in baseline screening42,69 and due to de novo infection.27,28 Studies have been conducted with TNF-inhibitor biologics, but there is little experience with other biologics and JAK inhibitors. Until there are specific studies with the new drugs, to ensure patient safety, the same recommendations as for TNF inhibitors will be maintained. Strategies to reduce the risk of tuberculosis must be adapted to these two different scenarios.

- 1

LTBI reactivation

Some cases of TB after proper LTBI screening have been associated with low sensitivity on the part of the TST and IGRAs in situations of immunosuppression.39,40 The CONVERT study found that repeating a TST (without a booster) a year after starting treatment with TNF inhibitors increases the probability of detecting LTBI in patients with IBD by 45%.70 With this strategy, after a follow-up of 798 patients/year, there were no cases of active TB; this represents a rate of active TB lower than those expected in Spain.17

It is known that the sensitivity of IGRA can be affected in patients treated with TNF inhibitors.39 However, the effect of TNF inhibitors on TST reactivity is debated. In patients with rheumatological disease and a positive baseline TST, TST results remains positive in the serial test performed during treatment with infliximab, and a relatively high rate of TST conversions has also been observed, which could be explained by management of inflammatory activity.71,72 However, in the CONVERT study, patients who received TNF inhibitors had a lower probability of positive conversion of a serial TST. This effect was independent of concomitant treatment with corticosteroids or IMMs.70 In all studies that simultaneously evaluated a TST and an IGRA during treatment with TNF inhibitors, the conversion rate of a TST was higher than the conversion rate of an IGRA.73–78 Meanwhile, in countries with a low to medium risk of tuberculosis, none of the patients who tested positive on the TST and received chemoprophylaxis developed active TB despite continuing with TNF inhibitors.70,71,76,77 Therefore, it can be concluded that, in this scenario, the TST is preferable as a test for LTBI detection in patients on treatment with TNF inhibitors.

In most studies, the serial TST was performed one year after the start of TNF inhibitors,70,71,73,75,76 since the risk of reactivation of LTBI is higher during the first year.1 In the CONVERT study, the conversion rate was five times higher in patients who were not receiving corticosteroids and/or IMMs at the time the TST was repeated one year after initiating biologic therapy. Therefore, in patients receiving corticosteroids and/or IMMs during baseline screening, it might be advisable to advance re-screening with a TST to eight weeks after stopping these drugs, without having to wait a year.70 If the re-screening is positive, chemoprophylaxis for LTBI is recommended, with no need to suspend the biologic therapy. There is insufficient data to recommend repeating the TST annually if the TST result for the first year is negative.

- 2

De novo TB infections

The European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) consensus recommends repeating the LTBI screening in all patients on treatment with TNF inhibitors who have been in contact with people with active TB or who have travelled to countries with intermediate to high rates of TB incidence, regardless of their length of stay in these countries. In these cases, screening is recommended 8−10 weeks after the contact or return from the trip.29 Healthcare personnel could benefit from screening for TB infection during biologic treatment, especially if they receive TNF inhibitors or JAK inhibitors.28 Other groups of patients who may be at higher risk of de novo infection with M. tuberculosis are those who provide home care for the elderly, those who work at closed institutions (prisons or nursing homes) and those who work with organisations that help immigrants, homeless people, etc. In this scenario, no studies have compared the TST to IGRAs, and screening should be done according to local practices and contact risk assessment.

LTBI chemoprophylaxis- 1

What is the efficacy of chemoprophylaxis in preventing reactivation of latent TB in patients receiving biologic treatment? Which is the most effective regimen?

LTBI chemoprophylaxis in patients who are candidates for treatment with TNF inhibitors has been shown to reduce the probability of developing active TB by up to 78%.79 Before starting LTBI treatment, it is necessary to rule out active TB by radiological evaluation. The most widely used regimen for LTBI treatment consists of isoniazid (INH) at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day (maximum 300 mg/day) for nine months.16 Randomised studies have shown protection rates exceeding 75% when a course of 9–12 months is completed (up to 90% if compliance is good), with protection falling to 60% when the duration of treatment is six months.80,81 The main causes of treatment failure are the presence of INH-resistant strains16 and adherence problems, which occur in up to 20% of patients in Spain.82 This regimen is recommended by the World Health Organization for countries with a low prevalence of TB, and it is the one recommended by most scientific guidelines and associations.13,83 The most common side effect of INH is hepatotoxicity, which occurs in up to 4% of patients, although it is serious in only 0.1%-0.3% of cases.84 For this reason, clinical monitoring of hepatic symptoms (jaundice or symptoms of hepatitis) is required, as is monthly monitoring of transaminases in patients with a history or increased risk of chronic liver disease (obesity, alcoholism or hepatitis C virus [HCV] infection). Treatment should be discontinued if there is an elevation of transaminases greater than three times normal values (in symptomatic patients) or five times the upper limit of normal (in asymptomatic patients).8,84

An alternative regimen is rifampicin (RIF) 10 mg/kg/day (maximum 600 mg/day) for four months. This regimen has an efficacy similar to that of INH for nine months, with a lower risk of hepatotoxicity and greater adherence.85 However, a limitation of this regimen is its high frequency of drug interactions, including interactions with corticosteroids and some immunosuppressants.86 Therefore, most clinical guidelines reserve its use for patients who present adverse effects with INH and for patients with suspected exposure to an INH-resistant strain of M. tuberculosis. Other regimens that have demonstrated similar efficacy and safety to the standard INH regimen are the combined regimen of INH 300 mg/RIF 600 mg for three months87 and the weekly regimen of INH 900 mg/rifapentine 900 mg for three months.88 These alternatives could be considered in patients at risk of poor adherence. Finally, the choice of the chemoprophylaxis regimen will depend on the characteristics of the patient and the antibiotic treatment policy at each centre.

- 2

Is it just as safe to start LTBI chemoprophylaxis and biologic treatment simultaneously as it is to start biologic treatment after 3–4 weeks of chemoprophylaxis?

There are no controlled studies on the ideal time to start biologic therapy in patients to be treated for LTBI. Most scientific associations recommend delaying the initiation of biologic treatment by 1–2 months after the initiation of LTBI treatment.13,29,83 This recommendation is arbitrary, though it is justified in part because most of the side effects of INH occur in the first two months.83 In a recent observational study of 27 patients with spondyloarthropathies, simultaneous administration of LTBI treatment (in this case, INH/RIF for four months) and adalimumab did not show any reactivation.89 Our recommendation is that, in most cases, it seems reasonable to delay the start of biologic treatment by at least three weeks, though in severe situations (e.g. severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis), the two treatments could be started simultaneously.

Active tuberculosis during biologic therapy- 1

When should active TB be suspected in a patient on biologic treatment? Is its clinical presentation different than in other scenarios?

Compliance with preventive measures, including chemoprophylaxis, does not completely eliminate the risk of developing active TB.42,69,90,91 Hence, it is necessary to maintain clinical surveillance so that TB, should it develop, may be diagnosed early.

A seminal study by Keane et al.1 found that extrapulmonary forms predominated among the forms of tuberculosis associated with TNF inhibitors (56%), including 24% of disseminated forms. These initial data were confirmed in subsequent series,42,69,90,92 with frequent diagnoses of lymph node TB, TB in serous membranes (pleura, peritoneum, meninges or pericardium) and TB in atypical sites. The time of onset of symptoms follows a dual pattern, with cases appearing in the first 3–4 months after the start of treatment in relation to LTBI reactivations1,42 and other late-onset cases, after more than a year, which suggest reinfections (although late reactivations cannot be ruled out).27

Although in the pulmonary forms the typical symptoms are cough, dyspnoea and chest pain, due to the high presence of disseminated and atypical forms, the predominant — and sometimes only — symptoms in TB associated with TNF inhibitors are general symptoms such as fever, asthenia and weight loss. Atypical symptoms may also be seen in relation to unusual sites (serous tissues [serositis], genitals, urinary tract, larynx or tongue).42,69 For this reason, patients must be warned about the symptoms of active TB, and clinicians must have a high degree of clinical suspicion to be able to make an early diagnosis and prevent the high morbidity and mortality associated with a diagnostic delay.1 In the event of the clinical suspicion, the diagnostic possibilities must be exhausted; this will often require not only direct microbiological diagnosis but also supporting methods such as radiological findings, determination of C-reactive protein (CRP) in biopsy samples and other indirect evidence of the presence of M. tuberculosis.16,42,62,90

- 2

How must time should pass before biologic treatment is restarted in IBD patients who have developed active TB during said treatment? Is there a higher risk of developing active TB again?

Existing evidence on the optimal time to restart biologic treatment in these patients is scarce. Patients who developed TB during clinical trials with biologics had the drug discontinued. Most scientific associations arbitrarily recommend suspending the biologic treatment at the time of TB diagnosis and not restarting it until TB treatment ends or at least two months after said treatment starts. This recommendation stems from expert opinion, though it is based on the need to assess the susceptibility, tolerance and efficacy of the tuberculostatic treatment.13,29 The exception is the British Thoracic Society, which does not recommend suspending treatment with TNF inhibitors in the event of developing TB, based on extrapolation of data from HIV patients in whom no differences in treatment efficacy were found between infected and uninfected patients.93 In addition, there are two published cases94,95 in which TNF inhibitors were expressly restarted during TB treatment as a strategy to manage TNF-dependent immune reconstitution syndrome, which often occurs during TB treatment in these patients following suspension of TNF inhibitors.96

There is some evidence from real-life series in which, for clinical reasons, TNF inhibitors were reintroduced early in tuberculosis treatment42,69,97 or even not discontinued at any time.98 In most of these patients, no problems with the efficacy or safety of the tuberculosis treatment were observed. Only one case has been published in the literature of recurrence of active TB after restarting a TNF inhibitor during TB treatment, with a new diagnosis of pulmonary TB 11 months after the end of the tuberculosis treatment.99

Regarding re-treatment with TNF inhibitors in patients having previously had properly treated TB, according to consensuses, these patients are not considered to be at special risk and chemoprophylaxis is not considered necessary. The above-mentioned series feature several cases in which treatment with TNF inhibitors was restarted more than a year after developing active TB and new TB reactivations were not found, except in a Turkish series of rheumatological patients.100 In some of these series, treatment with a different biologic (adalimumab, vedolizumab or ustekinumab) was restarted and no worsening or recurrence of tuberculosis was observed.69,101

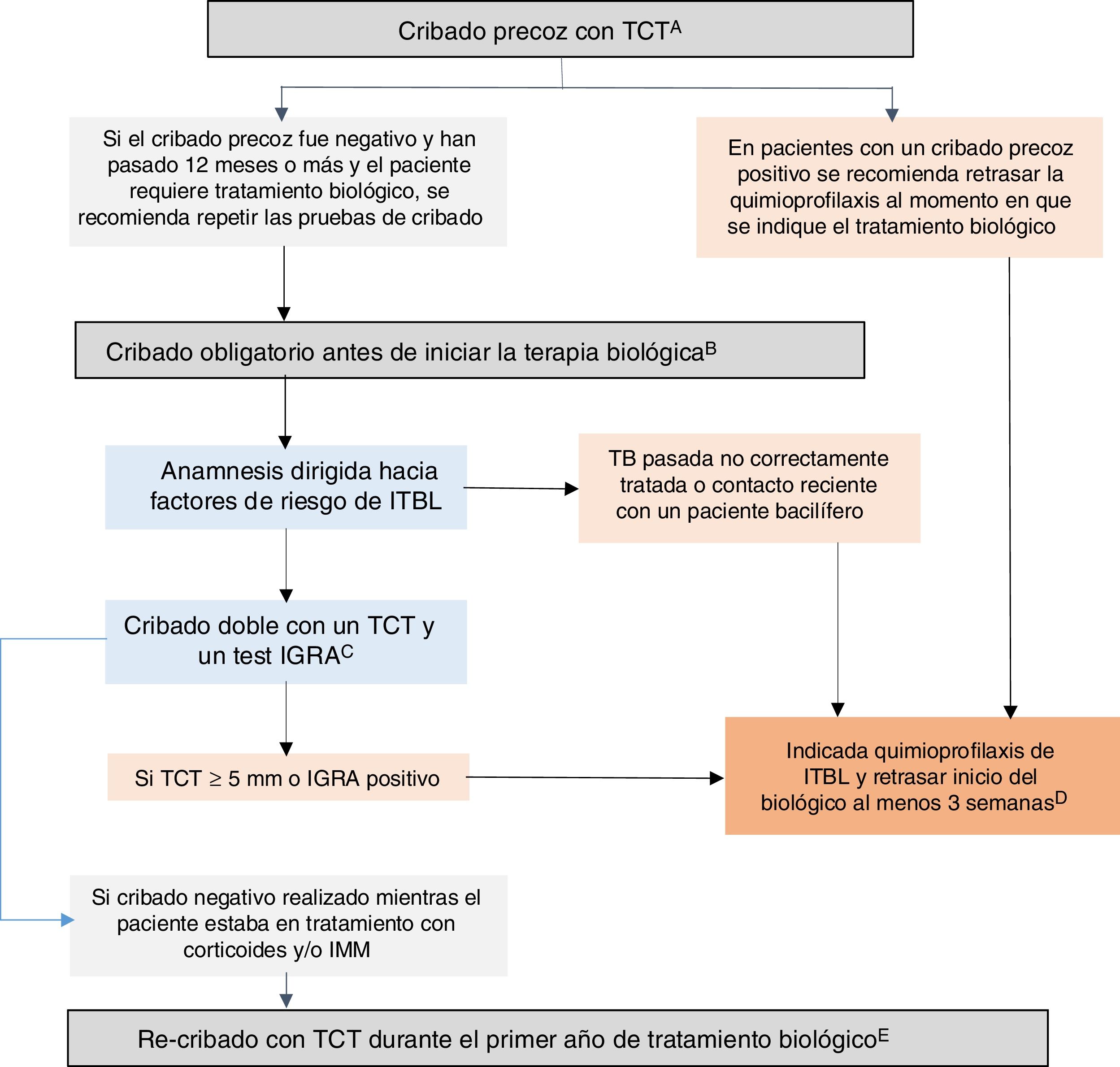

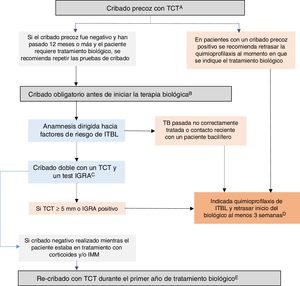

GETECCU 2020 recommendations on prevention and treatment measures for tuberculosis infection in patients with IBDBased on the evidence published up to December 2019 and the guidelines in this regard, the GETECCU recommendations on prevention and treatment measures for tuberculosis infection in patients with IBD are as summarised below (Fig. 1):

- 1

LTBI screening should be performed in all patients with IBD since, potentially, all of them could require treatment with biologic drugs or JAK inhibitors, which promote the development of active TB.

- 2

Early screening for LTBI is recommended at the time of IBD diagnosis, before starting immunosuppressive therapy (or up to two weeks after starting it) or, failing that, following treatment of the first flare-up (three weeks after stopping corticosteroids), preferably with a low inflammatory load. Alternatively, early screening can be done in any subsequent period during which the patient is in this situation of immunocompetence.

- 3

For this early screening in immunocompetent patients, a single TST screening test is recommended. Failing that, an IGRA could be considered a valid strategy, although it may be less sensitive for detecting old cases.

- 4

In patients with a positive early screening, it is recommended that chemoprophylaxis be delayed until biologic treatment is indicated. Compulsory screening should be repeated before starting biologic therapy in all patients if more than 12 months have elapsed since the previous negative screening, or earlier if it was not performed in a situation of immunocompetence.

- 5

Before initiating biologic or JAK-inhibitor therapy, compulsory screening should be done in patients without previous screening or with previous negative screening:

- -

a medical history focused on LTBI risk factors.

- -

when dealing with immunosuppressed patients (malnutrition, high inflammatory load and/or immunosuppression with corticosteroids and/or IMMs), it is recommended that double screening be done with a TST and an IGRA (either simultaneously or with the IGRA performed no more than three days after the TST). If an IGRA is not available, it is recommended that a second TST (booster) be performed 7–10 days after a first negative TST.

- -

- 6

A chest X-ray is only recommended in cases of positive screening or, in the event of recent contact with someone with tuberculosis, to rule out an active infection.

- 7

LTBI treatment is indicated for patients with a positive TST or IGRA result on screening tests or, in the case of patients with a negative TST or IGRA, if there is epidemiological evidence of improperly treated previous TB or of recent contact with a smear-positive patient.

- 8

It is recommended that the start of biologic treatment be delayed by at least three weeks after the start of LTBI chemoprophylaxis. In situations of serious illness, they can be started simultaneously.

- 9

The recommended regimen for LTBI treatment consists of INH at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day (maximum 300 mg/day) for nine months. Combination treatment with INH 300 mg and RIF 600 mg for three months is equally effective and safe. The choice of the chemoprophylaxis regimen will depend on the characteristics of the patient and the antibiotic treatment policy at each centre.

- 10

In patients with a previous negative screening performed while the patient was on treatment with corticosteroids and/or IMMs, re-screening with a TST is recommended during the first year after the start of biologic treatment.

- 11

During biologic treatment, possible primary tuberculosis infection should be monitored, especially in high-risk patients. Following contact with a smear-positive person or a trip to a region of with a high incidence of TB, it is recommended that screening be repeated after 8−10 weeks, even with a recent negative result.

- 12

Compliance with these recommendations does not completely eliminate the risk of developing active TB; therefore, it is necessary to maintain a high degree of clinical suspicion. In these cases, it is compulsory to perform all necessary diagnostic tests for ruling out or confirming TB. If active TB is diagnosed, it is recommended that treatment with TNF inhibitors or JAK inhibitors be suspended and that TB treatment be administered. TNF inhibitors or JAK inhibitors can be restarted after two months of tuberculosis treatment.

Recommended algorithm for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) screening in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). A) Early screening is understood as screening performed when there is still no indication for biologic therapy. Ideally, it should be performed when IBD is diagnosed, before the patient receives immunosuppression (or up to two weeks after starting immunosuppression) or, failing that, following treatment of the first flare-up (three weeks after stopping corticosteroids), preferably with a low inflammatory load. At diagnosis, there is often a high inflammatory load that precludes early screening; in these cases, it must be done in any subsequent period during which the patient is in a situation of immunocompetence. Failing that, an IGRA could be considered a valid strategy, although it may be less sensitive than a TST for detecting old cases. B) Compulsory screening is understood as screening performed when there is an indication for biologic or JAK-inhibitor therapy. This compulsory screening should be performed in patients no previous screening or with negative previous screening. C) Dual screening with a TST and an IGRA is recommended (either simultaneously or with the IGRA performed no more than three days after the TST). If an IGRA is not available, it is recommended that a second TST (booster) be performed 7-10 days after a first negative TST. D) In situations of serious illness, chemoprophylaxis and biologic therapy can be started simultaneously. E) In patients with a previous negative screening performed while the patient was on treatment with corticosteroids and/or IMMs, re-screening with a TST is recommended during the first year after the start of biologic treatment. If the re-screening is positive, chemoprophylaxis for LTBI is recommended, with no need to suspend the biologic therapy. IGRA: interferon-gamma release assay; IMMs: immunomodulators; TST: tuberculin skin test.

Sabino Riestra has received financial support for research or consulting from MSD, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Kern, Tillots, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals and Adacyte.

Carlos Taxonera has served as a guest speaker, consultant or advisor for MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Janssen, Ferring, Faes Farma, Dr Falk Pharma and Tillots.

Yamile Zabana has served as a guest speaker, consultant or adviser for Abbvie, Dr Falk Pharma, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Shire Pharmaceuticals and Tillots.

Daniel Carpio has received financial support for research or consulting from MSD, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Celltrion, Amgen, Chiesi, Tillots, Ferring, Dr. Falk Pharma and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Belén Beltrán has received consulting fees from Takeda, Pfizer, MSD and Fresenius.

Miriam Mañosa has received financial support for research or consulting from MSD, Abbvie, Kern, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Ferring, Faes Farma, Dr. Falk Pharma and Adacyte.

Ana Gutiérrez has received financial support for research or consulting from MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Takeda and Janssen.

Manuel Barreiro de Acosta has received financial support for research or consulting from MSD, Abbvie, Kern, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma and Adacyte.

None of these activities on the part the authors were related to this study.

Please cite this article as: Riestra S, Taxonera C, Zabana Y, Carpio D, Beltrán B, Mañosa M, et al. Recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) sobre el cribado y tratamiento de la infección tuberculosa en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:52–67.