This positioning document, sponsored by the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (Spanish Association of Gastroenterology), the Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva (Spanish Society of Digestive Endoscopy) and the Sociedad Española de Anatomía Patológica (Spanish Society of Pathology), aims to establish recommendations for the screening of gastric cancer (GC) in low incidence populations, such as the Spanish. To establish the quality of the evidence and the levels of recommendation, we used the methodology based on the GRADE system (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation). We obtained a consensus among experts using a Delphi method. The document evaluates screening in the general population, individuals with relatives with GC and subjects with GC precursor lesions (GCPL). The goal of the interventions should be to reduce GC-related mortality. We recommend the use of the OLGIM classification and to determine the intestinal metaplasia (IM) subtype in the evaluation of GCPL. We do not recommend establishing endoscopic mass screening for GC or H. pylori. However, the document strongly recommends treating H. pylori if the infection is detected, and investigation and treatment in individuals with a family history of GC or with GCPL. Meanwhile, we recommend against the use of serological tests to detect GCPL. Endoscopic screening is suggested only in individuals that meet familial GC criteria. As for individuals with GCPL, endoscopic surveillance is only suggested in extensive IM associated with additional risk factors (incomplete IM and/or a family history of GC), after resection of dysplastic lesions or in patients with dysplasia without visible lesion after a high-quality gastroscopy with chromoendoscopy.

Este documento de posicionamiento, auspiciado por la Asociación Española de Gastroenterología, la Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva y la Sociedad Española de Anatomía Patológica tiene como objetivo establecer recomendaciones para el cribado del cáncer gástrico (CG) en poblaciones con incidencia baja, como la española. Para establecer la calidad de la evidencia y los niveles de recomendación se ha utilizado la metodología basada en el sistema GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation). Se obtuvo el consenso entre expertos mediante un método Delphi. El documento evalúa el cribado en población general, individuos con familiares con CG y lesiones precursoras de CG (LPCG). El objetivo de las intervenciones debe ser la reducción de la mortalidad por CG. Se recomienda el uso de la clasificación OLGIM y determinar el subtipo de metaplasia intestinal (MI) para evaluar las LPCG. No se recomienda establecer cribado poblacional endoscópico de CG ni de H. pylori. Sin embargo, el documento establece una recomendación fuerte para el tratamiento de H. pylori sí se detecta la infección, y su investigación y tratamiento en individuos con antecedentes familiares de CG o con LPCG. En cambio, no se recomienda el uso de tests serológicos para detectar LPCG. Se sugiere cribado endoscópico únicamente en los individuos con criterios de CG familiar. En cuanto a los individuos con LPCG sólo se sugiere vigilancia endoscópica ante MI extensa asociada a algún factor de riesgo adicional (MI incompleta y/o antecedentes familiares de CG), tras la resección de lesiones displásicas o en pacientes con displasia sin lesión visible tras una endoscopia digestiva alta de calidad con cromoendoscopia.

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second most common type of gastrointestinal cancer. In Spain, as in the rest of Europe, the incidence of GC is at levels accepted as low. In 2018, there were an estimated 7765 new cases of GC, with an incidence rate adjusted to the world population of 9.2 cases/100,000 people in males and 4.3/100,000 people in females, and the adjusted mortality rates were 6.1/100,000 and 2.8/100,000, respectively.1 The incidence has been gradually decreasing in recent decades.

GC has a poor prognosis and remains associated with a high mortality rate,2 with five-year age-adjusted survival around 21% in males and 26% in females.3 This high mortality rate is due to multiple factors, including the fact that diagnosis is made in advanced stages and a limited response to chemotherapy. In an attempt to reduce the impact of GC, strategies for screening and treating the main cause of GC, Helicobacter pylori, have been put forward.3–8 Additionally, early detection programmes have been implemented in populations with a high prevalence of GC and surveillance programmes have been proposed in patients with precancerous lesions or conditions associated with an increased risk of developing GC.9

Gastric carcinogenesis is associated with H. pylori and occurs through a sequence of GC precursor lesions (GCPLs): atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia (IM) and dysplasia.9 Patients with these lesions could be candidates for measures to reduce the risk of GC, such as eradication of H. pylori, surveillance with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) and resection of lesions with a high risk of malignancy.10 The aim of any of these measures should be to reduce GC mortality rates in this group of high-risk patients through early detection and/or reduction in the incidence.

In recent years, many position statements have been published with varying points of view on important aspects of screening. The aim of this position statement is to put forward a set of consensus clinical practice recommendations after assessing the evidence and the different published clinical practice guidelines. The document deals with two different aspects in particular:

Determining which factors lead to an increased risk of GC, in particular family history of GC and histological precursor lesions of GC. In this regard, the histological criteria for the diagnosis of GC are assessed.

Assessing the efficacy of implementing the different strategies for reducing the incidence and/or mortality rate of GC in these situations (eradication of H. pylori and endoscopic surveillance) versus not implementing them, and making recommendations on their relevance.

These recommendations are aimed at preventing GC in low-incidence populations, which reflects the epidemiological situation in Spain. The following lie outside the scope of this document: prevention of diffuse GC, cardia GC and gastric neuroendocrine tumours; diagnosis of GC; diagnosis and surveillance in hereditary syndromes with predisposition to GC; and treatment of precursor lesions. This position statement is the fruit of a collaboration between the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology] (AEG), the Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva [Spanish Association of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy] (SEED) and the Sociedad Española de Anatomía Patológica [Spanish Association of Pathology] (SEAP) to arrive at a set of unified criteria and recommendations for clinical gastroenterologists, endoscopists and pathologists.

MethodsA working group of methodologists and experts from these associations was set up to research and review the evidence. The working group put forward the clinically important questions that are addressed in the statement. The GC incidence and mortality were determined to be important objectives.

To establish the levels of evidence and the strength of recommendations for the different questions addressed, we used the methodology based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group system.11 In so doing, we considered not only evidence quality, but also the risk-benefit balance, costs, and people's values and preferences. No recommendations were formulated or graded in the sections where this was not necessary, i.e. definitions and assessment of the GCPLs.

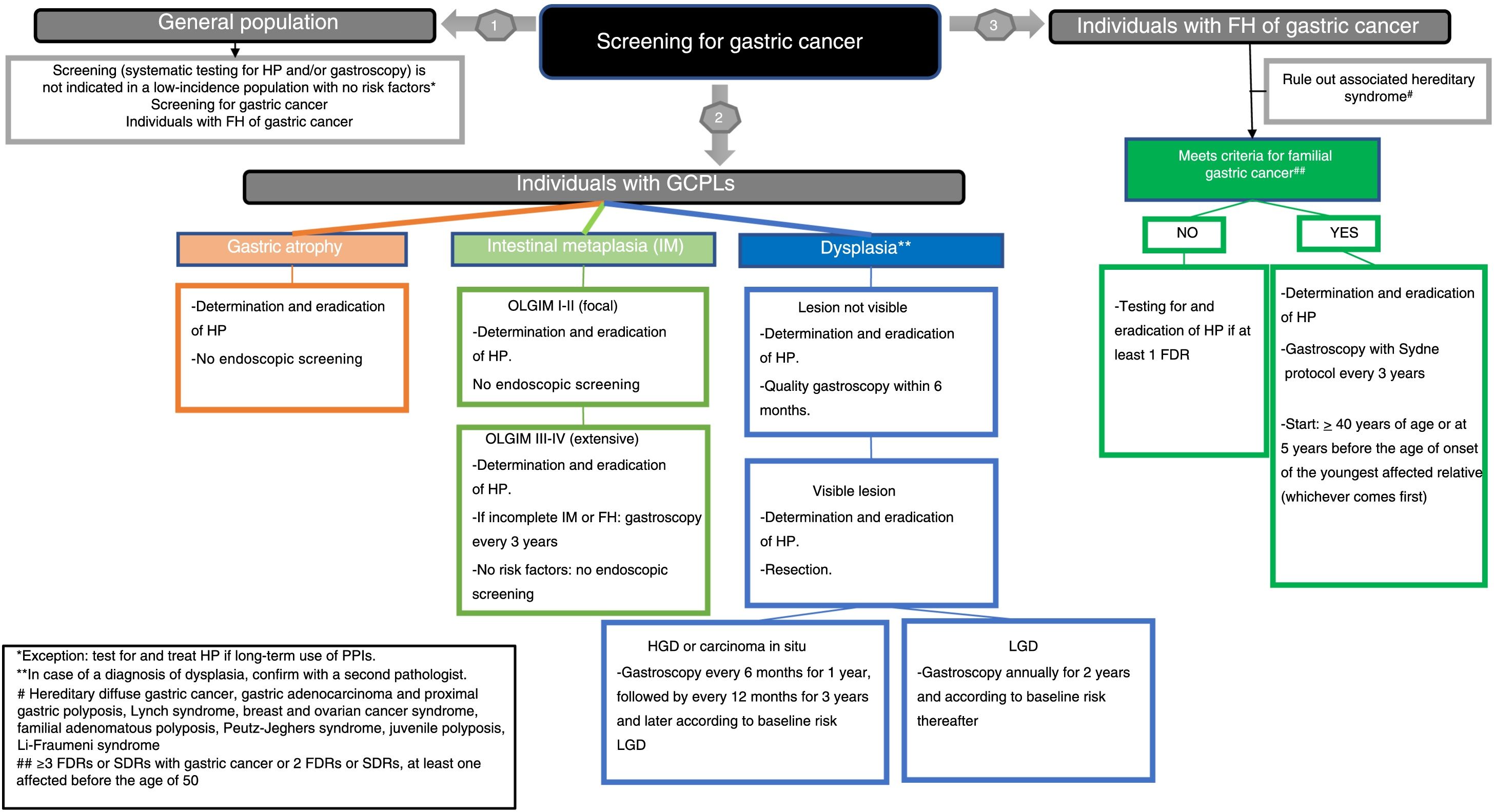

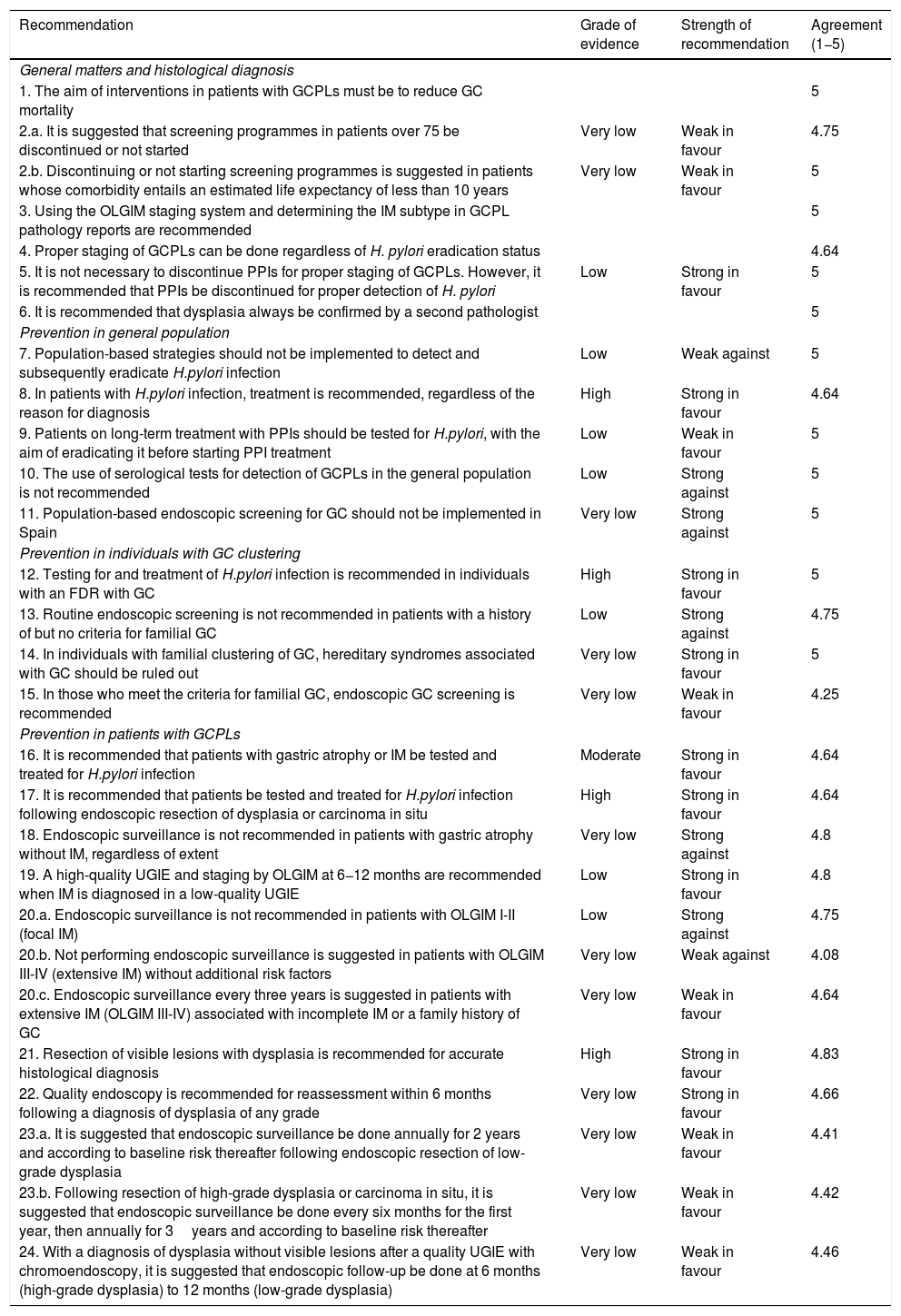

Once the recommendations were made, the agreement among the members of the working group was assessed. A consensus was achieved using the Delphi method. The recommendations were evaluated by the panel members using a Likert scale (1: strongly disagree; 2: disagree; 3: undecided; 4: agree; and 5: strongly agree). In the event of a disagreement, the recommendations were reformulated and voted on again. Those obtaining a final average agreement ≥4 (agree or strongly agree) were presented and substantiated. The first round of the Delphi consensus was done in November 2019 using the REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the AEG (www.aegastro.es).12 After reformulating the recommendations with agreement <4, a second round was held over two videoconferences on 22 May and 1 June 2020. Table 1 shows the final recommendations, together with an evaluation of the evidence, the strength of the recommendation and the degree of agreement. An algorithm is also included (Fig. 1). This position statement was approved by the boards of directors of the three scientific associations involved.

Recommendations of the position statement on gastric cancer screening in low-incidence populations. Includes grade of evidence, strength of recommendation and final expert agreement.

| Recommendation | Grade of evidence | Strength of recommendation | Agreement (1−5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General matters and histological diagnosis | |||

| 1. The aim of interventions in patients with GCPLs must be to reduce GC mortality | 5 | ||

| 2.a. It is suggested that screening programmes in patients over 75 be discontinued or not started | Very low | Weak in favour | 4.75 |

| 2.b. Discontinuing or not starting screening programmes is suggested in patients whose comorbidity entails an estimated life expectancy of less than 10 years | Very low | Weak in favour | 5 |

| 3. Using the OLGIM staging system and determining the IM subtype in GCPL pathology reports are recommended | 5 | ||

| 4. Proper staging of GCPLs can be done regardless of H. pylori eradication status | 4.64 | ||

| 5. It is not necessary to discontinue PPIs for proper staging of GCPLs. However, it is recommended that PPIs be discontinued for proper detection of H. pylori | Low | Strong in favour | 5 |

| 6. It is recommended that dysplasia always be confirmed by a second pathologist | 5 | ||

| Prevention in general population | |||

| 7. Population-based strategies should not be implemented to detect and subsequently eradicate H.pylori infection | Low | Weak against | 5 |

| 8. In patients with H.pylori infection, treatment is recommended, regardless of the reason for diagnosis | High | Strong in favour | 4.64 |

| 9. Patients on long-term treatment with PPIs should be tested for H.pylori, with the aim of eradicating it before starting PPI treatment | Low | Weak in favour | 5 |

| 10. The use of serological tests for detection of GCPLs in the general population is not recommended | Low | Strong against | 5 |

| 11. Population-based endoscopic screening for GC should not be implemented in Spain | Very low | Strong against | 5 |

| Prevention in individuals with GC clustering | |||

| 12. Testing for and treatment of H.pylori infection is recommended in individuals with an FDR with GC | High | Strong in favour | 5 |

| 13. Routine endoscopic screening is not recommended in patients with a history of but no criteria for familial GC | Low | Strong against | 4.75 |

| 14. In individuals with familial clustering of GC, hereditary syndromes associated with GC should be ruled out | Very low | Strong in favour | 5 |

| 15. In those who meet the criteria for familial GC, endoscopic GC screening is recommended | Very low | Weak in favour | 4.25 |

| Prevention in patients with GCPLs | |||

| 16. It is recommended that patients with gastric atrophy or IM be tested and treated for H.pylori infection | Moderate | Strong in favour | 4.64 |

| 17. It is recommended that patients be tested and treated for H.pylori infection following endoscopic resection of dysplasia or carcinoma in situ | High | Strong in favour | 4.64 |

| 18. Endoscopic surveillance is not recommended in patients with gastric atrophy without IM, regardless of extent | Very low | Strong against | 4.8 |

| 19. A high-quality UGIE and staging by OLGIM at 6−12 months are recommended when IM is diagnosed in a low-quality UGIE | Low | Strong in favour | 4.8 |

| 20.a. Endoscopic surveillance is not recommended in patients with OLGIM I-II (focal IM) | Low | Strong against | 4.75 |

| 20.b. Not performing endoscopic surveillance is suggested in patients with OLGIM III-IV (extensive IM) without additional risk factors | Very low | Weak against | 4.08 |

| 20.c. Endoscopic surveillance every three years is suggested in patients with extensive IM (OLGIM III-IV) associated with incomplete IM or a family history of GC | Very low | Weak in favour | 4.64 |

| 21. Resection of visible lesions with dysplasia is recommended for accurate histological diagnosis | High | Strong in favour | 4.83 |

| 22. Quality endoscopy is recommended for reassessment within 6 months following a diagnosis of dysplasia of any grade | Very low | Strong in favour | 4.66 |

| 23.a. It is suggested that endoscopic surveillance be done annually for 2 years and according to baseline risk thereafter following endoscopic resection of low-grade dysplasia | Very low | Weak in favour | 4.41 |

| 23.b. Following resection of high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in situ, it is suggested that endoscopic surveillance be done every six months for the first year, then annually for 3years and according to baseline risk thereafter | Very low | Weak in favour | 4.42 |

| 24. With a diagnosis of dysplasia without visible lesions after a quality UGIE with chromoendoscopy, it is suggested that endoscopic follow-up be done at 6 months (high-grade dysplasia) to 12 months (low-grade dysplasia) | Very low | Weak in favour | 4.46 |

FDR: first-degree relative; GC: gastric cancer; GCPL: gastric cancer precursor lesion; IM: intestinal metaplasia; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

At-risk population for GC. The at-risk population for GC is considered to be people with GCPLs who are potentially at increased risk of developing cancer.

Gastric atrophy. This is defined as loss of “appropriate glands” in the gastric mucosa.13 and includes two phenotypes: a) non-metaplastic atrophy, where there is a reduced number of glands in the gastric mucosa but no changes in the original type of glandular epithelium; and b) metaplastic atrophy, in which the normal glands in each gastric region are replaced by another gland type not typical of that region, including pseudopyloric metaplasia on mucosa in the corpus or fundus and intestinal metaplasia (IM).13

Intestinal metaplasia (IM). This is defined as replacement of the glandular and foveolar epithelium of the gastric mucosa by intestinal epithelium.14 The most widely used classification is the one that distinguishes between two types of IM: a) complete IM, in which the gastric mucosa acquires the phenotype typical of the small bowel mucosa; and b) incomplete IM, in which the gastric mucosa appears similar to the colonic mucosa.

Indefinite for dysplasia/neoplasia / dysplasia / intraepithelial neoplasia / non-invasive neoplasia. Dysplasia is an epithelial proliferation with definite cytological and architectural atypia, but no evidence of infiltration.15–17 Depending on the degree of abnormality in the architecture and the cytological atypia, dysplastic lesions are classified as low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in situ. The diagnosis “indefinite for neoplasia/dysplasia” is used in the presence of an inflammatory component or artefacts precluding a diagnosis of dysplasia, which should not be considered innocuous, as 26.8% of resected lesions were found to be cancerous (5% adenomas and 21.8% carcinomas).18

Familial GC with no known genetic cause. One of the clinical situations involving higher risk is familial GC (FGC), in which familial clustering of GC of intestinal histology is seen with no identified hereditary cause. It is defined by the following criteria: a) >3 first-degree relatives (FDRs) or second-degree relatives (SDRs) with GC, regardless of age, or b) >2 FDRs or SDRs with GC, at least one of whom is under 50.19

Intramucosal carcinoma/invasive intramucosal carcinoma. This is a carcinoma that invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae, without submucosal infiltration (pT1a).

Early gastric cancer (EGC). This includes pT1a and pT1b (with submucosal infiltration), and is independent of lymph node status. Usually, there are distinctive architectural abnormalities, such as marked glandular density, a cribriform pattern, budding, glandular proliferation or desmoplasia.

Quality UGIE. This refers to an endoscopic examination performed with a high-definition endoscope following a systematic protocol with representative photos of all regions and lesions, with a minimum duration of 7min.20–22

Population risk of GC. Risk is defined based on age-adjusted incidence rate. A region is defined as high risk when the annual incidence is greater than 20/100,000 inhabitants, intermediate risk if it is 10–20/100,000 and low risk if it is less than 10/100,000.23

ResultsThe expert group selected and answered the following questions:

General1. What should be the objective of the interventions evaluated in patients with GCPLs?

The objective of the interventions in patients with GCPLs must be to reduce GC mortality.

Agreement 5.

2. Up to what age is gastric cancer screening recommended?

It is suggested that screening programmes in patients over 75 be discontinued or not started.

Very low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.75.

Discontinuing or not starting screening programmes is suggested in patients whose comorbidity entails an estimated life expectancy of less than 10 years.

Very low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 5.

EvidenceThe World Health Organization (WHO) defines screening as presumptive identification of unrecognised diseases or defects by means of tests, examinations or other procedures that can be done quickly and easily in the target population. Screening is used to detect serious chronic diseases such as cancer, in which a reduction in mortality rates is the primary objective. The requirements to determine the suitability of a screening strategy were initially defined by WHO in 1968 and subsequently updated by the UK National Screening Committee in 2015.24,25 In the case of cancer, the objectives are to reduce the incidence and, primarily, cancer-specific mortality. The effect on mortality should be determined within clinical trials, population registries and registries specific to the population subject to screening. As this means monitoring a target population for many years, the results will not be seen in the short term, so, once the screening programme has started, it is recommended that intermediate indicators be monitored.26 In the specific case of GC screening, early detection and treatment of gastric high-grade lesions and carcinomas in situ, in addition to interval cancer rates, could be an effective intermediate indicator.

The benefit of screening the general population may be limited by age and comorbidity, both of which reduce the life expectancy of the patient and increase the risks and complications of invasive procedures. Screening is unlikely to significantly modify life expectancy when this is less than 10 years due to a patient's underlying disease. As an example, the risk of death in Spain at the age of 75 is 2.1% per 100 individuals per year and increases rapidly; by the age of 80 it is already 3.7 per 100 per year.27 Furthermore, the risk of procedures and potential surgery also increases with comorbidity and age. For all these reasons, it is suggested that GC screening be discontinued — or not started in the first place — at 75 years of age or when the patient's life expectancy is clearly less than ten years.28

Histological diagnosis3. Which histological method is recommended for classifying risk?

Using the Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) staging system and determining the IM subtype in GCPL pathology reports are recommended.

Agreement 5.

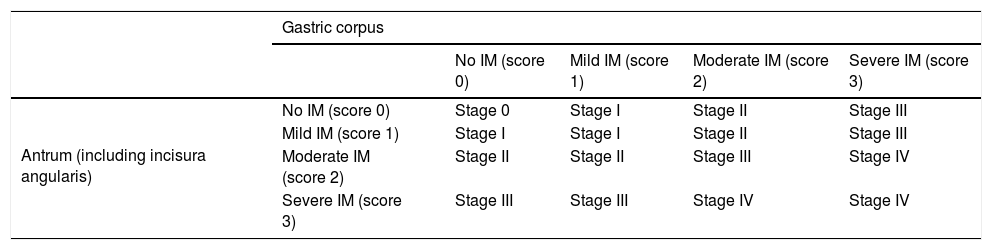

EvidenceThe Sydney classification14 allows semi-quantitative assessment of the severity of precursor lesions. However, it does not provide prognostic information to help identify patients with a higher risk of lesion progression in clinical practice. For this reason, two systems have been proposed for histological grading and staging of chronic gastritis: OLGA (Operative Link for Gastritis Assessment),29 based on the extent and severity of gastric atrophy and not distinguishing non-metaplastic from metaplastic atrophy; and OLGIM,30 based exclusively on the extent and severity of the IM (Table 2). The two systems coincide in that the risk of cancer is concentrated in advanced stages (OLGA III/IV or OLGIM III/IV). Two cross-sectional studies31,32 and a cohort study33 using the OLGA system and a follow-up study34 using the OLGIM system have highlighted their ease of use and utility in identifying patients at risk of progression. Both systems are currently recommended.10 However, whereas the diagnosis of atrophy shows great intra- and inter-observer variability,35,36 the level of agreement for IM is almost perfect — three times higher than for atrophy.30 Therefore, some authors believe that the OLGIM system is more appropriate than the OLGA system for identifying patients with GCPLs at high risk of progression. Thus, the extent of the IM is the most reliable diagnostic parameter for predicting the risk of GC.30 Additionally, incomplete IM is a significant marker of progression of lesions and development of gastric carcinoma,37–39 and the follow-up of patients with incomplete IM may increase the likelihood of diagnosing early gastric cancer (EGC).40,41 After H. pylori eradication, patients with incomplete IM have a higher risk of developing GC than those with complete IM after 12 years of follow-up (odds ratio [OR]: 11.3; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.4–91.4).42 Moreover, the finding of incomplete IM in a gastric biopsy is an indicator of extensive IM.38,43 Therefore, IM type should be routinely included in pathology reports.

Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia Assessment (OLGIM) classification.

| Gastric corpus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No IM (score 0) | Mild IM (score 1) | Moderate IM (score 2) | Severe IM (score 3) | ||

| Antrum (including incisura angularis) | No IM (score 0) | Stage 0 | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III |

| Mild IM (score 1) | Stage I | Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | |

| Moderate IM (score 2) | Stage II | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | |

| Severe IM (score 3) | Stage III | Stage III | Stage IV | Stage IV | |

IM: intestinal metaplasia.

Adapted from Capelle et al.30

Both the OLGA and OLGIM systems enable classification of risk in patients with GCPLs based on severity and extent of gastric atrophy and IM, respectively. The two systems coincide in that stage III and IV patients are at high risk of progression to GC. The low intra- and inter-observer diagnostic agreement in the case of atrophy compared to the almost perfect diagnostic agreement for IM make the OLGIM system the most reliable diagnostic parameter for predicting the risk of GC. Determining the presence of incomplete IM may provide additional information on GC risk.

4. Is it necessary to eradicate H. pylori to properly stage GCPLs?

GCPLs can be properly staged regardless of H. pylori eradication status.

Agreement 4.64.

A systematic review and two meta-analyses showed that eradication of H. pylori improved gastric histology and even normalised it in the early stages of the disease.44–46 In these stages, chronic gastritis and gastric atrophy without metaplasia were found to decrease in severity one to two years after H. pylori eradication,45 although in the case of atrophy this could vary by extent and location.46 The two meta-analyses concluded that there is no significant improvement in IM after H. pylorieradication.44,46 However, a more recent randomised clinical trial (RCT) showed that, in patients with GCPLs, eradication of H. pylori achieved regression of both atrophy and IM after both six and twelve years of follow-up in a significant percentage of patients.47,48 The same study also showed regression of low-grade dysplasia (LGD) in some cases.47,48 By contrast, regression of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) is very rare.49 Considering that patients who may be candidates for monitoring are those with epithelial dysplasia, atrophy and/or extensive IM and these lesions do not vary in the short term, despite H. pylori eradication treatment, prior eradication would not be necessary to perform proper staging of these patients.

5. Is it necessary to discontinue proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for proper staging of GCPLs?

It is not necessary to discontinue PPIs for proper staging of GCPLs. However, it is recommended that PPIs be discontinued for proper detection of H. pylori.

Low quality of evidence, strong recommendation in favour.

Agreement 5.

There are no studies specifically assessing the need to discontinue PPIs for quality gastroscopy. There are also no studies showing that PPIs interfere with the histological diagnosis of atrophy and/or IM.50 In studies in rodents, using PPIs increased the risk of developing atrophic gastritis in the corpus and cancer,51 probably due to PPIs' acidity-inhibiting effect.52 There are no specific studies assessing whether or not PPI treatment affects accurate diagnosis of GCPLs, but multiple studies have shown that the use of PPIs can mask the presence of H. pylori.53

Expert opinionThe quality of evidence for the available data is very low and does not support a recommendation on the need to discontinue PPIs prior to performing follow-up gastroscopy of GCPLs. It is necessary, however, to discontinue PPIs at least two weeks prior to the initial endoscopy so as to avoid false negative diagnoses of H. pylori as a result of these drugs.54

6. When should dysplasia be confirmed by a second pathologist?

It is recommended that dysplasia always be confirmed by a second pathologist.

Agreement 5.

The Padova classification of gastric dysplasia shows good reproducibility and minimal inter-observer variability among pathologists with experience in gastrointestinal diseases.17 This classification made it possible to unify the terminology between Western and Japanese pathologists. The Vienna classification is currently the most widely used.16 In 2009, the WHO15 modified the classification of dysplasia, renaming it intraepithelial neoplasia, maintaining the three diagnostic categories proposed in the Padova classification due to their ease of use: negative for intraepithelial neoplasia; indefinite for intraepithelial neoplasia; and high-grade/low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.49 Where the diagnosis is indefinite for dysplasia, a repeat biopsy is recommended. Although the prognosis of "indefinite for dysplasia" is usually benign, histological review by a second pathologist with experience in gastrointestinal pathology is recommended, as up to 26.8% of resected lesions with a diagnosis of indefinite for dysplasia/neoplasia were cancerous18,55,56 and review of the diagnosis of indefinite for dysplasia by expert pathologists changed the diagnosis to dysplasia in 11/46 patients, especially in those with risk factors.44,55,56 The diagnostic criteria for gastric intraepithelial neoplasia are a matter of global debate, with kappa values ranging from 0.74 to 1, depending on the institution. The overall kappa value is 0.83, indicating excellent agreement. However, the agreement for the different diagnoses is 91.5% for carcinoma, 86.3% for low-grade dysplasia and 50.8% for high-grade dysplasia. This shows that the diagnostic criteria for carcinoma are more reproducible than those for dysplasia; therefore, dysplasia should always be confirmed by a second pathologist.57

Expert opinionThe reproducibility of the dysplasia classification is far less certain among non-expert pathologists. For this reason, a second opinion should be sought when the histological findings indicate the need for endoscopic treatment and in cases with a diagnosis of indefinite for dysplasia, dysplasia of any grade or carcinoma in non-targeted random biopsies.18,57

GC screening in general population7. Are H. pylori screening and treatment recommended in the general population to reduce gastric cancer mortality?

Population-based strategies should not be implemented to detect and subsequently eradicate H. pylori infection.

Low quality of evidence, weak recommendation against.

Agreement 5.

8. Is eradication therapy recommended in patients with H. pylori infection?

Treatment of H. pylori infection is recommended, regardless of the reason for diagnosis.

High quality of evidence, strong recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.64.

EvidenceEradication of H. pylori in the general population in high-prevalence areas significantly reduces GC incidence and mortality.3–5 The results come from both meta-analysis of RCTs and meta-analysis of observational studies.3,6,58 The reduction in the risk of GC is very similar in all studies (OR: 0.46 for observational studies; 0.54 for RCTs) with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 72 to prevent a case of GC and 137 to prevent a GC-related death.6 Cost-effectiveness studies are highly heterogeneous but agree that eradication is cost-effective.59 Nevertheless, there is no evidence on the effect of implementation of population-based strategies for H. pylori detection and subsequent eradication, especially in areas with a low incidence of GC such as Spain.60

Expert opinionThe level of evidence on the effect of H. pylori eradication on reducing the incidence of GC is strong, with a NNT of approximately 125 to prevent a case of GC. Non-invasive, high-precision tests for the diagnosis of H. pylori and treatments with high eradication rates are available. Furthermore, eradication of H. pylori is recommended in Spain as a treatment strategy for uninvestigated dyspepsia, peptic ulcer and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Therefore, eradicating H. pylori in a patient with known infection is justified at the individual level, regardless of the reason that led to the diagnosis.54

There are, however, factors against recommending a population-based screening programme: a) The acceptability of diagnostic tests for and, in particular, treatment of H. pylori in asymptomatic individuals is unknown; b) The potential rates of the population participating in a screening programme are therefore unknown; and c) There are also no data on the effects on resource use, psychological impact or efficacy in a population with a low incidence of GC60 like that of Spain. Therefore, the recommendation with regard to implementation of population-based strategies is weak against it, except within prospective studies, preferably clinical trials. The panel advises a viability assessment of the different population-based treatment options in Spain using models. For this type of model to be reliable, the actual prevalence of H. pylori at the present time needs to be determined, as the available data are not recent and the prevalence of infection is lower in younger cohorts.61

9. Is it necessary to test for H. pylori infection in patients on long-term treatment with PPIs?

Patients on long-term treatment with PPIs should be tested for H. pylori, with the aim of eradicating it before starting PPI treatment.

Low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 5.

EvidenceLong-term use of PPIs worsens atrophic gastritis in the corpus in patients with H. pylori. This may increase the risk of GC, according to the results of a case-control study that included patients with reflux disease and H. pylori who underwent long-term treatment with PPIs versus fundoplication (81% versus 59%; p=0.007).62,63 Moreover, in studies in rodents, using PPIs increased the risk of developing atrophic gastritis in the corpus and cancer,51 probably due to PPIs' acidity-inhibiting effect.52 According to a recent review of 16 studies in 1920 patients who received long-term treatment with PPIs, patients with H. pylori have a higher risk of atrophic gastritis in the corpus than those without.64

Expert opinionAlthough there is currently no clear evidence that PPIs increase the risk of GC, it is known that long-term use of PPIs in H. pylori-infected patients increases the risk of progression to GCPLs. Given the association between GCPLs and GC, as a precautionary measure, young patients requiring prolonged treatment with PPIs should be tested for H. pylori and treated if positive.7H. pylori treatment has very low morbidity and mortality rates, and the associated financial costs are low, while the potential long-term benefit is high.54 Nevertheless, it does not seem necessary to recommend H. pylori testing in the older population requiring ongoing treatment with PPIs, given the lack of evidence on the preventive effect in this population.

Use of serological tests for detection of GCPLs10. Are serological tests recommended for detection of GCPLs?

The use of serological tests for detection of GCPLs in the general population is not recommended.

Low quality of evidence, strong recommendation against.

Agreement 5.

EvidenceDetermination of circulating pepsinogen I/II has been suggested as a useful test for detecting patients with precancerous lesions. Two meta-analyses have reviewed the benefits of serological tests, finding a sensitivity of 60%-69% and a specificity of 88%-89% for the diagnosis of precancerous lesions.65,66 Other combinations have been suggested which include clinical data plus a combination of serology for H. pylori, pepsinogen and gastrin. The sensitivity and specificity of this classification are similar to those with the use of pepsinogen alone.67 Studies in Spain using a diagnostic test combining pepsinogen, gastrin-17 and serology for H. pylori have shown even lower diagnostic precision, with a sensitivity of 50% and a specificity of 80%.67 Knowing the prevalence of GCPLs is important when assessing the efficacy of a potential screening programme. Although the quality of the data is very heterogeneous, the prevalence in routine endoscopies of advanced lesions with a significant risk of progression to GC — including extensive IM and dysplasia — can be estimated at 7%.68 In Spain, the prevalence of advanced lesions was even lower — 4% in a series by McNicholl et al.69 Evaluation of serological tests is complicated by the varied methodology used in different studies.

Expert opinionThe population-based use of serological tests with low sensitivity and specificity <90% for detection of GCPLs in the context of a low prevalence (below 10%) would, on the one hand, generate a very high number of individuals with false positive results who will require endoscopy and, on the other hand, mean that only half of GCPLs would be detected.69 To this it must be added that there is no evidence that screening for advanced lesions prevents GC. Therefore, if the efficacy of GCPL screening in preventing GC has not been demonstrated, the case for serological screening of the general population to detect GCPLs should be rejected.

Endoscopic screening11. Is endoscopic screening in the general population recommended for preventing GC?

Population-based endoscopic screening for GC should not be implemented in Spain.

Very low quality of evidence, strong recommendation against.

Agreement 5.

EvidenceThree-quarters of all new cases of and deaths due to GC occur in Asian countries, particularly China, Japan and Korea. In 1960, Japan began a massive annual radiological screening programme for GC. Since then, screening has been introduced in other countries by way of periodic UGIE. The evidence on the efficacy of such screening is moderate, and the results are not homogeneous. In Japan, several case-control and cohort studies, primarily conducted between 1980 and 2000, showed a 40%–60% reduction in GC mortality with radiological screening.70 However, subsequent studies have not confirmed an association between radiological study and a reduction in mortality.70

Clinical and epidemiological studies have shown that the accuracy of upper endoscopy is better than that of radiology.70 However, there is no definitive evidence to show that endoscopic GC screening reduces mortality rates. In China, a prospective study on endoscopic surveillance in high-risk populations showed no reduction in GC mortality (standard mortality ratio 1.01; 95% CI: 0.77–1.57).71 By contrast, Hamashima et al.72 found a 30% reduction in GC mortality in the population subjected to endoscopic screening in Japan. Jun et al.73 analysed the effect of the Korean national screening programme in a case-control study. Twice-yearly endoscopy significantly reduced GC mortality by approximately 50% (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.51−0.56), whereas the barium study had no effect (OR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.95–1.01). The data from this study therefore suggest that screening in high-risk populations does have an effect on mortality. However, this type of study is subject to a considerable risk of bias. In summary, the evidence in favour of screening in high-risk populations is limited. There are no data on the efficacy of population-based screening in low-risk areas.

Cost-effectiveness studies have focused on endoscopic IM screening and follow-up of high-risk patients with extensive metaplasia. These studies have shown that cost-effectiveness depends on the prevalence of extensive IM and the rate of progression from metaplasia to cancer, and have suggested that screening could be cost-effective in medium- and high-risk populations. Different strategies for detecting IM by endoscopy have been assessed using cost-effectiveness models. Most have suggested that it is not a cost-effective strategy in low-risk populations. Two cost-effectiveness studies have suggested that screening for GC and IM by upper endoscopy at the time of colonoscopy for colon cancer screening, with subsequent surveillance of GCPLs, could be cost-effective in medium- and high-risk areas.10,74 A study by Pimentel-Nunes study suggested that screening could be effective in risk groups with an annual incidence of GC of more than 10 cases per 100,000 people per year. According to these data and the prevalence published in Spain, endoscopic screening could be useful only in selected high-risk populations in certain areas of Castile-Leon and Galicia.75,76

Expert opinionThere are factors against recommending the implementation of a population-based screening programme with endoscopy. The potential rates of participation of the population in a screening programme are unknown. There are also no data on the effects on resource use, psychological impact or efficacy in a population with a low incidence of GC like that of Spain. The available data are based on indirect cost-effectiveness studies. They are heterogeneous and suggest that endoscopic screening for GC and IM is not effective in low-risk populations. There are neither clinical data to support screening nor solid data on which to base the assumptions of cost-effectiveness studies.

Patients with a family history of GC12. Should patients with an FDR with GC be tested and treated for H. pylori?

Testing for and treatment of H. pylori infection is recommended in individuals with an FDR with GC.

High quality of evidence, strong recommendation in favour.

Agreement 5.

13. Is endoscopic screening recommended in patients with a family history of GC but no criteria for familial GC?

Routine endoscopic screening is not recommended in patients with a history of but no criteria for familial GC.

Low quality of evidence, strong recommendation against.

Agreement 4.75.

14. Is a family study necessary in patients with criteria for familial GC?

In individuals with familial clustering of GC, hereditary syndromes associated with GC should be ruled out.

Very low quality of evidence, strong recommendation in favour.

Agreement 5.

15. Is endoscopic screening recommended in familial GC with no known genetic cause?

In those who meet the criteria for familial GC, endoscopic GC screening is recommended.

Very low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.25.

EvidenceThe aetiology of GC is multifactorial; the main environmental agents include H. pylori, diet and smoking. Although most cases of GC are sporadic, familial clustering is found in approximately 10% of cases.77,78 Hereditary GC, that is, GC in the context of an associated germline mutation, accounts for 1%-5% of all cases of GC.79 Family characteristics suggesting a hereditary predisposition include having several affected relatives, an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, being affected at an early age and association with other extragastric cancers. Based on family and personal history, plus the histological type of the tumour (diffuse or intestinal), the patient should be assessed in terms of clinical diagnostic criteria for a situation with a hereditary basis associated with an increased risk of GC. If found, the corresponding germline genetic testing should be performed and endoscopic screening should be established based on the associated hereditary syndrome.79 If a hereditary syndrome is ruled out, a diagnosis of familial GC is made if the criteria for familial clustering are met. If they are not, the patient will be considered to have sporadic GC.

FDRs of a GC patient have an increased risk of developing this type of cancer. However, the magnitude of this risk varies by ethnic group, geographic region and degree of familial clustering. According to several case-control studies, the highest risk in FDRs is generally in the range of 1.5–3.5 times higher,80 but it can be up to 10 times higher than the general population depending on the country.81 A recent meta-analysis of 32 studies assessing the risk of GC in FDRs revealed a 2.5 times higher risk of GC in FDRs compared to the general population. However, in the vast majority of studies, no genetic testing was performed to rule out a hereditary component.82 In Spain, there is one case-control study which included individuals with 1 FDR or 2 SDRs with GC, reporting an OR of 3.4 (95% CI: 1.9–6.0) compared to the control group.83

One of the clinical situations involving higher risk is familial GC (FGC), in which familial clustering of GC of intestinal histology is found with no identified hereditary cause. The risk of GC increases with the number of family members affected. A study in 2010 showed that the risk of GC with an FDR was 2.7 (OR: 2.7; 95% CI: 1.7–4.3), with this risk increasing to 9.6 (OR: 9.6; 95% CI: 1.2–73.4) in individuals with two or more affected FDRs.84 Another previous study also showed that having two or more FDRs carried a greater risk of GC than only one affected FDR (OR: 5.5; 95% CI: 3.0–10.2 vs OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.3–2.1) and that the risk was greater if the affected FDR was a sibling versus a parent (siblings: OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.8–3.7; parents: OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.3–2.2).85

Members of the same family tend to have similar environmental factors such as socioeconomic status and dietary habits, and may even be infected with the same strain of H. pylori. Therefore, the results of studies aimed at assessing family history of GC as an independent risk factor for this type of cancer should be interpreted with caution. For example, a case-control study identified H. pylori infection and family history as independent risk factors for GC, although the two were positively related to each other. Thus, individuals with FDRs with GC and H. pylori had an eight times higher risk of GC (OR: 8.2; 95% CI: 2.2−30.4) and a 16 times higher risk of non-cardia GC (OR: 16.0; 95% CI: 3.9–66.4) than individuals with neither a family history nor H. pylori infection. However, it is impossible to analyse the risk of GC in individuals with a family history but without H. pylori infection, as 82% of the cohort with a family history were positive for H. pylori.86

There is no scientific evidence or general consensus on the advisability of periodic gastroscopies or the interval between them. The most widely accepted recommendation at present is detection and eradication of H. pylori in FDRs of patients with GC.77,78,87 A recently published randomised control trial showed that, with a follow-up of 9.2 years, eradication of H. pylori reduces the risk of GC, both by intention to treat (eradication 1.2%, placebo 2.7%, HR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.21−0.94) and by effective eradication (eradication 0.8%, non-eradication 2.9%, HR: 0.2; 95% CI: 0.1−0.7).88

As regards endoscopic surveillance in familial GC, the recommendations are based on expert consensus. These recommendations are very heterogeneous, ranging from the recommendation not to do routine gastroscopies (within the framework of research only) to performing gastroscopies annually or every three or five years. As previously mentioned, having a family history of GC carries an increased risk of H. pylori infection, gastric atrophy and IM, and there is evidence to suggest that gastric precancerous lesions in individuals with FDRs with GC have a higher risk of progression.89 On that basis, some expert groups have suggested performing surveillance gastroscopies (with high-definition endoscopy and/or chromoendoscopy and taking targeted biopsies) every three years in patients with gastric atrophy or IM and a history of FDRs with GC.10

In individuals who meet criteria for familial GC, the expert consensus of the 2018 European Society of Digestive Oncology (ESDO) recommends annual screening with UGIE, similar to that used in the follow-up of individuals who meet criteria for hereditary diffuse GC with no identified germline mutation, from the age of 40 or five years before the age of onset in the youngest affected relative.90 This examination must be performed according to the Cambridge protocol91: a) use of a high-definition endoscope; b) careful inspection for 30min; c) gastric insufflation and deflation manoeuvres; d) use of mucolytics; e) biopsy of all mucosal abnormalities; f) serial biopsies (30 random biopsies are recommended, six from each region: antrum, incisura, corpus, fundus and cardia); and g) detection and eradication of H. pylori.

Expert opinionAs Spain is a low-risk country for GC, while solid scientific evidence is awaited, gastroscopies with biopsies according to the Sydney protocol and determination of H. pylori in biopsies will be recommended every three years10 from the age of 40, or five years before the age of onset in the youngest affected relative, exclusively in individuals from families with criteria for familial GC. In individuals with a family history of GC who do not meet the criteria for familial GC or a hereditary syndrome, testing for and eradication of H. pylori will be recommended. Finally, given the lack of scientific evidence and the highly heterogeneous follow-up of individuals with a family history of GC, it is essential that prospective studies be conducted in order to acquire a deeper understanding of GC risk based on family clustering and establish suitable screening and surveillance measures.

Management of patients with GCPLsEradication of H. pylori in patients with GCPLs16. Should patients with atrophy or IM be tested and treated for H. pylori?

It is recommended that patients with gastric atrophy or intestinal metaplasia be tested and treated for H. pylori infection.

Low quality of evidence, strong recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.64.

17. Should patients with dysplasia or carcinoma in situ be tested and treated for H. pylori?

It is recommended that patients be tested and treated for H. pylori infection following endoscopic resection of dysplasia or carcinoma in situ.

High quality of evidence, strong recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.64.

Evidence- •

Advanced cancer. A non-systematic search found no data to suggest any significant effect of H. pylori eradication on treatment or survival in patients with advanced GC.

- •

Carcinoma in situ/HGD. High-quality RCTs92,93 and several meta-analyses94–97 have been published with highly concordant results. These studies have shown that effective eradication of H. pylori reduces the development of metachronous lesions in approximately 50% of patients who have required endoscopic mucosal resection for EGC or carcinoma in situ.

- •

IM/gastric atrophy and low-grade dysplasia (LGD). In a technical review conducted by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) for clinical practice guidelines on IM, eradication of H. pylori reduced the risk of GC mortality (RR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.38–1.17) and GC incidence (RR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.48−0.96) both overall and specifically in patients with IM, although in the case of IM the reduction was not significant (RR 0.76; 95% CI: 0.36–1.61).98 Recent RCTs also showed that eradication of H. pylori is associated with regression of IM at six and twelve years post-treatment in a significant percentage of patients.47,48 Those same studies also showed regression of LGD in some cases.47,48 By contrast, regression of HGD is very rare.49

Treatment of H. pylori has a clear protective effect against the development of metachronous lesions in patients who undergo endoscopic resection of high-grade gastric lesions. Although data on the efficacy of H. pylori infection treatment based on previous histology are limited, there are data suggesting that it may be effective in reducing the incidence of GC in patients with atrophy and, in particular, IM. The data are as follows:

- a)

The published meta-analyses show a non-significant numerical trend in favour of treating H. pylori.

- b)

Said treatment is effective in preventing metachronous lesions in patients who have received endoscopic treatment for cancerous lesions, and most of these patients are have atrophy and/or IM.

- c)

There is evidence that treating H. pylori could induce regression of advanced lesions in an undetermined percentage of patients.

Moreover, H. pylori treatment has very low morbidity and mortality rates, and the associated financial costs are low. In view of all the above, the quality of the evidence can be deemed low, but a strong recommendation in favour can be made.

Endoscopic surveillance and management of GCPLsGastric atrophy without metaplasia18. Is endoscopic surveillance recommended in patients with gastric atrophy without IM?

Endoscopic surveillance is not recommended in patients with gastric atrophy without IM, regardless of extent.

Very low quality of evidence, strong recommendation against.

Agreement 4.8.

EvidenceThe annual incidence of GC has been determined to be 0.1%-0.25% in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis.99,100 However, there is significant variability in the calculation of those figures. For example, in a Swedish study, the cumulative incidence at 20 years was approximately 2% in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis.101 A Japanese study found a higher cumulative incidence of GC at 5 years, reaching 1.9%–10% in patients with extensive chronic atrophic gastritis.102 A recent systematic review included 19,749 patients with atrophic gastritis, 261 of whom progressed to GC out of a total follow-up of 171,170 person-years. The incidence range for GC in this cohort was 0.53–15.24 per 1000 person-years. Most studies reported an incidence rate of 1.0–5.2 per 1000 person-years, and only two studies had more extreme results.103 Specifically in Spain, González et al.104 reported GC in 156 individuals with chronic atrophic gastritis over a follow-up period of 12 years.

Risk of GC increases with extent and degree of gastric atrophy; for example, an increased relative risk of GC of up to 5.76 has been reported in patients with severe atrophic gastritis of the corpus compared to those with minimal or no gastritis.100,105 Another Japanese study reported a relative risk of GC of 1.7 in patients with moderate atrophic gastritis and 4.9 in patients with severe atrophic gastritis, compared to individuals with no atrophy or mild atrophy.106 In another study, the extent of gastric atrophy was related to the risk of GC detection: 5.33% in patients with atrophy in the entire stomach versus 0% and 0.25% in patients with atrophy limited to the antrum and atrophy in the incisura or corpus, respectively.107

Finally, with regard to risk of dysplasia, in a retrospective study of patients with an undefined stage for dysplasia on baseline endoscopy and with OLGA staging, with a median follow-up of 31 months, no dysplasia was detected in any patients with OLGA 0/I/II, but six cases of dysplasia were detected in 25 patients with OLGA III/IV during said follow-up.108

Expert opinionThe incidence of cancer in patients with extensive atrophy is not known, but may be in the region of 1 case per 1000 patients per year. One of the reasons for the difference in risk reported in the various studies is probably that some studies have not considered the extent or degree of atrophy in calculating the incidence of GC and/or dysplasia. Another important limitation is that the OLGA classification does not distinguish between metaplastic and non-metaplastic atrophy in the classification of atrophic gastritis, which makes interpretation of the results difficult. The diagnosis of atrophy on its own without taking IM into account has very high interobserver variability, making it a poor risk marker. Moreover, screening is not recommended as several of the key conditions established by regulatory agencies for recommending screening by are not met. There are no data on the acceptability of a screening programme and, above all, there is no evidence either in randomised studies or in observational studies that screening reduces the mortality rate. There are also no data on the potential impact on the healthcare system, and there is no provision of resources for screening. In this context, screening is not recommended, pending data from future prospective studies. This reasoning is applicable to all GCPLs, but carries more weight in more difficult-to-characterise GCPLs, such as gastric atrophy, and in lower-risk situations, such as complete and/or localised IM.

Intestinal metaplasia19. Is it necessary to repeat the UGIE after the initial diagnosis of IM?

A high-quality UGIE and staging by OLGIM at 6−12 months are recommended when IM is diagnosed in a low-quality UGIE.

Low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.8.

20. Is endoscopic surveillance recommended in patients with IM?

Endoscopic surveillance is not recommended in patients with OLGIM I-II (focal IM).

Low quality of evidence, strong recommendation against.

Agreement: 4.75.

Not performing endoscopic surveillance is suggested in patients with OLGIM III-IV (extensive IM) without additional risk factors.

Very low quality of evidence, weak recommendation against.

Agreement 4.08.

Endoscopic surveillance every three years is suggested in patients with extensive IM (OLGIM III-IV) with incomplete IM or a family history of GC.

Very low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.64.

EvidenceIM should be considered a risk factor for GC if it affects the mucosa of the corpus and the antrum. A total of ten cohort studies, including 25,912 patients with IM and a follow-up of 159,756 patient-years, assessed progression of IM to GC. The incidence density of GC was 12.4 (95% CI: 10.7–14.3) cases of GC per 10,000 patient-years, with a cumulative incidence of GC at three, five and ten years of 0.4, 1.1 and 1.6%, respectively.98,109

As part of the AGA technical review to inform the clinical practice guidelines on IM, three factors that increased the risk of developing GC in patients with IM were identified.98,109 Having one or more FDRs with GC increased the risk 4.5 times (OR: 4.53; 95% CI: 1.33–15.46) in the four studies that analysed this factor compared to those with no FDRs with GC. Seven studies evaluated the risk of developing GC based on the histological type of IM. Incomplete IM was associated with an increased risk of GC during a follow-up of 3–12.8 years (RR: 3.33; 95% CI: 1.96–5.64). With regard to extent of IM, only two studies provided information for assessing risk during follow-up. Extensive IM was associated with a non-significant increase in the risk of GC (RR: 2.07; 95% CI: 0.97–4.42). These data are consistent with those from various case-control studies in which an association was found between extensive IM (OLGIM III/IV) and GC detection.110–113

Another risk factor widely associated with an increased risk of GC, pernicious anaemia, was assessed in this review. Only one study that evaluated the prevalence of IM in pernicious anaemia was identified. Although the incidence of IM was high, 88.9% (95% CI: 70.8-96.6%), the study had multiple limitations: sample size (27 patients), diagnostic criteria and potential selection biases. Therefore, this document does not make a separate recommendation for patients with pernicious anaemia/autoimmune gastritis and proposes establishing the indication for surveillance in these patients in the same way as in the general population, based on the histological lesion and additional risk factors.98,109

In Europe, a recent Swedish study that analysed more than 400,000 patients concluded that IM (regardless of the degree of extension) significantly increases the risk of GC. This study showed that a second UGIE with biopsies can have significant prognostic value, as GCPL regression (IM no longer detected) can occur during follow-up, and this is associated with a lower risk of progression to GC.101

However, the prevalence of focal IM in the European population is around 16%-18%, and it seems unreasonable to consider surveillance of these patients.114 Also, although the same authors believed that IM could increase the risk of GC compared to the absence of IM or even just atrophy, the risk seems too low to justify surveillance.42

Once again, as mentioned in the case of gastric mucosal atrophy, there are no RCTs on the benefits or risks of endoscopic surveillance in patients with GCPLs.98,109 The evidence comes from non-experimental studies with selection biases and different diagnostic criteria and surveillance schedules.40,110,115 One cohort study compared the risk of detection of GC and stage at diagnosis between a group of 166 individuals with diagnoses of IM, dysplasia, ulcers or polyps and endoscopic surveillance for 10 years, and a group of 1753 patients with no surveillance. In the group of patients in the surveillance programme, there was a higher percentage of cases of GC diagnosed in early stages and an increase in 5-year survival among patients who underwent surgery.115 However, most of the cancers were detected during monitoring of suspected gastric ulcers and/or in the first year of follow-up, suggesting that many of the lesions were incipient cancers undiagnosed in the index UGIE. Therefore, the results are not applicable to screening. In the most recently published study, 279 patients with GCPLs had at least one surveillance endoscopy during a mean follow-up interval of 57 months. Four cases with HGD or GC were detected, all in individuals with OLGIM III-IV.110 Another recently published retrospective study analysed the factors associated with the development of GC in 332 patients with atrophic gastritis and a mean follow-up of 9.2 years in an Asian population. During the follow-up period, 16 GC were detected with an incidence of 0.53/1000 patient-years. This study corroborated that the factors associated with the risk of GC detection are the extent of the GCPLs and H. pylori infection. Overall, endoscopic surveillance did not reduce the risk of GC. However, in individuals with extensive GCPLs, a multivariate analysis suggested that endoscopic surveillance at 2−3year intervals reduced the risk of GC (HR: 0.01; 95% CI: 0.001−0.34). The limitations of this study were its lack of determination of GCPL extent, its retrospective nature and the fact that it included different surveillance periods.116

Expert opinionThe increase in the risk of GC associated with IM is limited. In patients with GCPLs, the risk of developing GC is confined mainly to patients with dysplasia or extensive IM (OLGIM III-IV). In the case of extensive IM, this risk increases when there are other associated risk factors such as incomplete IM or a family history of GC. However, there is no evidence linking autoimmune atrophic gastritis to a higher risk of GC detection in IM.98,109,114 The risk of GC in patients with focal IM (OLGIM I-II) is very low — in fact, it is not significantly higher than in the general population. As indicated in the AGA technical review,98,109 there is no quality evidence to recommend endoscopic surveillance in patients with IM. Prospective studies are required to evaluate the effect of endoscopic surveillance on the incidence of GC in these patients.

Furthermore, the conditions required by regulatory agencies are not met. There are no data on the acceptability of a screening programme or on the potential impact on the healthcare system, and there is no provision of resources for screening. In this context, screening is not recommended, pending data from future prospective studies.

The panel agrees that research in this field is needed. Therefore, it is recommended that the risks and benefits of screening be discussed with patients with extensive IM, and that the non-recommendation and the lack of evidence on efficacy be made clear. Given the low quality of the evidence, screening would be reasonable if the patient showed a preference in this regard. Both those who agree and those who do not should be included in a registry that evaluates the effectiveness of long-term screening. Outside of clinical research, there is no scientific evidence to recommend screening.

However, in patients with several risk factors (extensive IM associated with incomplete IM and/or a family history of GC), offering endoscopic surveillance has been considered reasonable, provided the unproven reduction in the risk of GC versus the risks and discomfort associated with this type of screening are discussed with the patient. This is intended, first, to offer screening to patients with a higher potential risk and, second, to have data on the potential usefulness of screening in Spain in these higher-risk patients, which will enable evaluation of its effectiveness.

There is no information on the effect of the risk of autoimmune origin on the risk of developing GC in IM associated with pernicious anaemia. Consequently, we do not recommend specific surveillance in these patients. Based on expert opinion, some consensus statements have suggested that an interval of 2−3years may be suitable in patients with extensive IM who require endoscopic surveillance. In our case, in view of the lack of evidence, it was decided to recommend the use of the same criteria for follow-up proposed for patients with GCPLs.

Dysplasia and carcinoma in situ21. Is endoscopic resection recommended in patients with dysplastic lesions?

Resection of visible lesions with dysplasia is recommended for accurate histological diagnosis.

High quality of evidence, strong recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.83.

22. Is a repeat endoscopy recommended following a diagnosis of dysplasia without visible lesions?

Quality endoscopy is recommended for reassessment within 6 months following a diagnosis of dysplasia of any grade.

Very low quality of evidence, strong recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.66.

EvidenceLGD has traditionally been described as having a significant risk of progression to GC. However, no studies have evaluated this risk in a large number of patients, and those that have been conducted have included LGD and moderate dysplasia in the same group. Furthermore, these studies feature no information on whether the lesions were visible or invisible. For example, a study conducted in the United States that included 141 individuals with LGD under endoscopic surveillance reported an incidence of GC of 7.7/1000 person-years, with a relative risk of 25.6 (95% CI: 9.4–55.7) and a median time of 2.6 years for progression to GC.117 Similarly, a cohort study conducted in the Netherlands reported an annual risk of progression from mild or moderate dysplasia to GC of 0.6%.100 However, these results were not confirmed in a more recent study, also conducted in the Netherlands, in which none of the prospectively followed-up cases with LGD progressed to HGD or GC after a mean follow-up period of 4.7 years.110

No studies have examined whether endoscopic resection of visible lesions with LGD reduces the incidence or mortality rates of GC and/or HGD compared to no treatment.100 In any event, the finding of dysplasia is a risk marker for GC. In some studies,100 a high number of patients with GC were detected in the first year of follow-up of patients with HGD; therefore, a short-term reassessment is recommended in these patients. Those with mild or moderate dysplasia should also be reassessed, but the interval is not well defined and could be from six months to a year. LGD is also a potential sign of malignancy, as many biopsies of visible lesions may be negative for dysplasia and obscure a true neoplasm due to a sampling error.118 A Western series that studied specimens from submucosal endoscopic dissections found that histological staging with an upward trend occurs after endoscopic resection (ER) in 33% of lesions.119 Similarly, an Eastern study that analysed 1850 lesions detected a discrepancy of 32% between endoscopic biopsies and ER specimens.118 A meta-analysis that specifically investigated the possibility of upward re-staging of LGD after ER showed that this occurs in 25% of lesions, with 7% being definitively determined to be GC.120

Expert opinionThe diagnosis of LGD is problematic, as biopsies have been reported to under-stage dysplasia, and many visible LGD lesions are actually already malignant.121 In a meta-analysis that analysed changes in LGD staging after endoscopic resection, reclassification to more advanced stages was reported in up to 25% of the lesions, 7% of which were already malignant.120 Detailed examination of the lesions with magnification endoscopy and virtual chromoendoscopy such as narrow-band imaging enables identification of certain characteristics suggestive of worse histology,122 but this technique is not widely available in Spain. For that reason, the recent “Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach” (MAPS II) guidelines recommend that all visible lesions (including those with LGD) should be resected.10

23. What type of endoscopic follow-up should be done following resection of a lesion with dysplasia?

It is suggested that endoscopic surveillance be done annually for 2 years and according to baseline risk thereafter following endoscopic resection of LGD.

Very low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.41.

Following resection of HGD or carcinoma in situ, it is suggested that endoscopic surveillance be done every six months for the first year, then annually for three years and according to baseline risk thereafter.

Very low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.42.

EvidenceThe prevalence of dysplasia (in general) in routine endoscopies ranges from 0.5% to 3.75% in Western countries and from 9% to 20% in regions with a high incidence of GC, such as Colombia and China.123 There is evidence to suggest that patients with HGD have a high risk of progression to cancer110 and of synchronous neoplasia.124 A recent cohort study demonstrated that HGD was an independent risk factor for GC (HR: 18.8; 95% CI: 9.0–39.5). The standardised incidence of GC was 2.0 (95% CI: 1.5–2.6) in the subgroup of individuals without dysplasia and 35.2 (95% CI: 15.2–69.4) in the subgroup with HGD.125 However, the real risk of progression from dysplasia to cancer is not well defined due to the difficulty of finding prospective, well-designed studies with proper biopsy that analyse the natural history of dysplasia. The rate of HGD becoming malignant ranges from 25% to 85% with a time interval between 4 and 48 months, depending on the study.126 For example, a Dutch study reported that 25% of patients diagnosed with HGD developed GC within the following year.100 An important factor in the variability of the incidence of GC secondary to gastric HGD is the high rate of discrepancy in the diagnosis of HGD. Although biopsy is the standard method for HGD diagnosis, malignant lesions are underdiagnosed in 40%–66% of cases compared to the analysis following resection.127–129

Moreover, after curative ER of a gastric neoplasm, other lesions may appear in the gastroscopies performed during follow-up. These lesions may be of new onset, not detected in previous gastroscopies or the result of the progression of previously invisible lesions that were already present in a preclinical phase. As this distinction is often difficult to make, new (metachronous) lesions are defined by consensus as those that appear at a distance from the original cancer at least one year after ER.130 Lesions that appear during the first year are therefore considered to be synchronous cancers not detected during the initial gastroscopy. The data on the overall incidence of metachronous GC after ER show a great deal of variability in the literature, with figures ranging from 2.7% to 15.6%.130

A retrospective study that included 947 patients assessed the incidence of gastric cancer after ER of EGC with a median follow-up of 2.3 years.131 The incidence of GC was 14.4 cases per 1000 person-years after LGD resection and 18.4 cases per 1000 person-years after resection of HGD and/or EGC, without statistically significant differences. There were also no differences in the cumulative incidence of gastric cancer and an increased risk was only identified in the detection of invasive GC in the LGD group. In another retrospective study, published by Cho et al.,132 2779 patients with 2981 lesions (518 cases of HGD and 2463 cases of EGC) were included with a median follow-up of 42 months. The cumulative incidence of metachronous lesions at five and ten years was 4.6% and 10.5%, respectively, and the annual incidence was 0.9%, with no statistically significant differences between patients with HGD and those with EGC. The annual incidence of metachronous lesions was 1.02% in the HGD group and 0.88% in the EGC group. Again, one of the most important limitations of this study was the high percentage of dropouts from follow-up during the first year. Another retrospective, single-centre study of Korean origin133 reported the incidence of metachronous cancers in 641 patients who underwent ER for dysplastic gastric lesions (84% LGD and 16% HGD) after a median follow-up of 29 months. The annual incidence of metachronous lesions was 1.26%, and the cumulative incidence of metachronous cancers five years after ER of dysplastic lesions was 31%. In the multivariate analysis, male sex (OR 2.3; 95% CI: 1.3–4.2), IM (OR 1.9; 95% CI: 1.2−3.0) and HGD (OR 2.7; 95% CI: 1.16–6.26) were independent risk factors for the development of metachronous lesions. Finally, a recent retrospective study, which included 316 endoscopically resected gastric cancers, also evaluated the risk of metachronous lesions based on three histological groups — LGD, HGD and EGC — over a median follow-up of 4.2 years.134 The incidence of GC after ER was 15.2 cases per 1000 person-years in the LGD group, 18.5 cases per 1000 person-years in the HGD group and 20.9 cases per 1000 person-years in the EGC group. The incidence of metachronous cancers was 28.6, 45.7 and 39.7 cases per 1000 person-years in the LGD, HGD and EGC groups, respectively, with no statistically significant differences between the different groups. In the multivariate analysis, the only independent risk factor for the development of cancers or metachronous GC was male sex.

Expert opinionThe available studies have multiple limitations in both design and follow-up. Also, the data come exclusively from the Asian population, so extrapolation to a Western environment entails a certain likelihood of bias. However, the figures for incidence of metachronous cancers are consistent across the different studies analysed. Overall, the rate of onset of new lesions following ER of lesions with HGD/intraepithelial cancer is very high, with 10–20 cases per 1000 person-years. This enables recommendation of close monitoring, particularly following resection of HGD or carcinoma in situ.

24. What type of endoscopic follow-up should be done in dysplasia without visible lesions?

With a diagnosis of dysplasia without visible lesions after a quality UGIE with chromoendoscopy, it is suggested that endoscopic follow-up be done at 6 months (HGD) to 12 months (LGD).

Very low quality of evidence, weak recommendation in favour.

Agreement 4.46.

EvidenceIn a 2011 prospective study by Simone et al.,135 three expert endoscopists reassessed 20 patients with a diagnosis of invisible dysplasia. The examinations were performed with high-definition endoscopes, mucolytic lavage and virtual or conventional chromoendoscopy. A total of 18 visible lesions were identified: 13 cases of high-grade dysplasia and 5 cases of carcinoma. In 2016, Yep-Gamarra et al. conducted a prospective study in Spain136 that included 50 patients with a histological diagnosis of a pre-malignant lesion in the previous 6 months. The authors performed a protocolised gastroscopy with chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine and acetic acid, resulting in a higher percentage of patients diagnosed with dysplasia and visible lesions.

Expert opinionDetection of dysplasia in random biopsies is not uncommon. As set out in this document, numerous factors can contribute to the failure to detect a lesion in conventional gastroscopy. Although the evidence supporting this recommendation comes from observational studies, we believe that a quality gastroscopy focused on the detection of dysplastic lesions is the fundamental step for the problem of invisible dysplasia, as it enables identification of resectable lesions in a significant percentage of patients.

No studies evaluating the optimal follow-up interval in patients with invisible dysplasia after quality gastroscopy were found. Considering that the presence of dysplasia is a factor for the development of gastric carcinoma137 and the risk of not having detected an existing lesion, we believe high-quality endoscopic reassessment is advisable within a maximum of 6−12 months, depending on whether the patient has HGD or LGD.10

FundingThis position statement received no external funding. Joaquín Cubiella has received funding from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Health Institute] through project PI17/00837 (co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund “A way to make Europe"/"Investing in your future”).

Conflicts of interestXavier Calvet has received research grants from Abott, MSD, and Vifor; has received fees for advisory meetings from Abott, MSD, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen and VIFOR; and has lectured for Abbott, MSD, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda and Allergan.

The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cubiella J, Pérez Aisa Á, Cuatrecasas M, Díez Redondo P, Fernández Esparrach G, Marín-Gabriel JC, et al., en representación de la Asociación Española de Gastroenterología, la Sociedad Española de Endoscopia Digestiva y la Sociedad Española de Anatomía Patológica. Documento de posicionamiento de la AEG, la SEED y la SEAP sobre cribado de cáncer gástrico en poblaciones con baja incidencia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:68–86.