The present study aimed to investigate the interplay between adult attachment style, perceived social support, and post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms among adult female victims of sexual assault)SA(. While prior research has established the link between insecure attachment style and PTS, the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. The potential role of perceived social support as a mediator in this relationship has been largely neglected and there is a dearth of studies investigating this mediation among victims of SA. The present study sought to address this gap in literature. Two hundred twenty-six women who have endured SA completed self-report measures of attachment style, perceived social support, and PTS, using an online survey. The results confirmed the anticipated pattern, showing a positive correlation between insecure attachment styles and PTS, as well as a negative correlation with perceived social support. A mediation analysis indicated that perceived social support may be a mechanism linking attachment styles to PTS. Following SA, insecurely attached women, especially those with avoidant attachment, have difficulties relying on and utilizing support from their environment, which may render them more susceptible to PTS. Nevertheless, the mediation was partial, indicating that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance independently contribute to the development and maintenance of PTS.

Sexual assault (SA) is a pervasive form of violence affecting millions worldwide. Studies on victimization consistently report high global prevalence rates, with women experiencing higher rates than men (e.g., ARCCI, 2022; Borumandnia et al., 2020; García-Pérez et al., 2023; Leemis et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023; Vílchez Jaén et al., 2022). According to the World Health Organization, approximately 1 in 3 women has experienced non-partner sexual violence or physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence in their lifetime (WHO, 2021).

SA is a significant public health issue, with profound implications for the physical and mental well-being of victims (e.g., Moyano & Sierra, 2014). It often results in long-term psychological trauma, manifested in various forms of psychological dysfunction. Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress (PTS) and development of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are prevalent, as well as other conditions, such as depression and anxiety (Gueta, 2022). As one of the most distressing events a person can experience, the influence of SA on mental health appears to be more pronounced than that of other types of traumas (Dworkin et al., 2017, 2023).

Nevertheless, despite the high rates of mental health issues associated with SA, many survivors do not develop significant stress symptoms or mental illness. The accepted etiological model for psychopathology is the diathesis-stress model, positing that the likelihood and severity of psychological symptoms following a traumatic event are determined by the interaction between predisposing factors (diathesis) and environmental stressors. Individual vulnerabilities or predispositions that increase susceptibility to developing PTS following trauma exposure include genetic factors, personality traits, early life experiences, or pre-existing mental health conditions (McKeever & Huff, 2003). The individual's attachment style also constitutes one of these vulnerabilities (Mikulincer et al., 2015).

Post-traumatic stress and attachment styleAttachment is a core aspect of personality (Gagliardi, 2021). The comprehensive biopsychosocial model of attachment theory delineates characteristic ways of relating in close relationships, resulting from the quality of the individual's interactions with caregiving figures during infancy. When caregivers consistently and sensitively attend to the child's needs, trust is built, and a secure attachment is nurtured. Conversely, persistent disregard or rejection by caregivers results in the formation of an avoidant attachment, expressed by the child's avoidance of seeking support and protection, and difficulty in appropriately expressing emotions. Inconsistent responses from caregivers may result in the formation of anxious attachment, characterized by heightened levels of anxiety and hypervigilance in interpersonal relationships, as well as difficulties in emotional regulation and expression (Bowlby, 1973, 1980, 1982).

The early relationships with the caregivers become ingrained as mental representations of self and others, which give rise to the development of internal working models, influencing the shaping of cognition, emotions, and expectations in subsequent relationships (Bowlby, 1980; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2008). Adults who developed a secure attachment system in infancy have internalized dependable relationships with their caregivers. Consequently, they are able to exhibit adaptability in various social relationships and maintain a balanced interplay between self-regulation and interpersonal stress regulation. On the contrary, adults with insecure attachments, whether avoidant or anxious, often experience impaired abilities in these domains (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

During times of stress, attachment insecurities may hinder the restoration of safety and emotional well-being, manifested in mental health symptoms. The link between attachment and PTS has been studied in a variety of populations, including war prisoners (e.g., Dieperink et al., 2001; Mikulincer et al, 2011), veterans (e.g., Escolas et al., 2012), victims of domestic violence (Scott & Babcock, 2010), and victims of child abuse (e.g., Ensink et al., 2021; Sandberg, 2010). A meta-analysis of the total effect of 46 studies across a wide range of traumas indicated a medium negative relationship between secure attachment and PTS and a medium positive relationship between insecure attachment and PTS (Woodhouse et al., 2015). Similarly, a recent systematic review of 21 studies on the links between adult attachment and PTS concluded that secure attachment may be a protective factor against PTS, whereas attachment insecurity appears to increase vulnerability, especially when the trauma is of an interpersonal nature. Nevertheless, the mechanisms that account for the influence of secure and insecure attachment styles on PTS are poorly identified and understood (Barazzone et al., 2019). Among these mechanisms may be the differential utilization of social support by securely and insecurely attached individuals (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007, 2008).

Attachment, social support, and post-traumatic stressEmpirical studies have established the protective role of social support in the development of PTS, underscoring the significance of both received and perceived support (e.g., Dworkin et al., 2018; Johansen et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021; Zalta et al., 2021). Greater support, perceived or received, is associated with reduced PTS and better mental health.

Given the crucial role social support has in enhancing resilience against PTS, factors that shape and influence the way individuals perceive and utilize support from their environment are of great importance (Dark-Freudeman et al., 2020; Jittayuthd & Karl, 2022). Attachment style may play a pivotal role in affecting social support perception and utilization in general, particularly in times of distress.

When faced with a threat, the attachment system is triggered, prompting a need for proximity to external or internalized attachment figures, to obtain protection, comfort, support, and relief. For securely attached individuals, internalized positive experiences of comfort and responsiveness and positive cognitions of the attachment figures may serve as internal resources that facilitate receiving support and enhance resilience in the aftermath of trauma. Conversely, for insecurely attached individuals, negative experiences, and cognitions of the unavailable or unreliable attachment figures, hinder the ability to benefit from the environment (Mikulincer et al., 2015; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007, 2008).

Mikulincer and Shaver's (2007) theory of attachment system activation and functioning elucidates how attachment operates in adulthood, detailing how the attachment internal working models manifest in proximity-seeking behaviors when individuals encounter stress or distress. The theory posits that each attachment style is characterized by distinct pathways that affect PTS. Prompted by the attachment system cues to seek and receive support, securely attached adults seek and rely on support within close relationships. In contrast, individuals who are avoidantly attached distance themselves and disregard these internal cues, while anxiously attached individuals dramatically intensify proximity-seeking behaviors in a desperate desire to receive support.

The present studyDespite the established interrelations between attachment style, social support, and PTS, the role of social support as a mediator in the relationship between adult attachment style and PTS is understudied (Besser & Neria, 2012; Jittayuthd & Karl, 2022; Shallcross et al., 2014; Volgin & Bates, 2016). To our knowledge, this mediation has not been investigated in the context of sexual trauma. The present study aimed to investigate the interrelations between adult attachment style, perceived social support, and symptoms of PTS and distress among female victims of sexual violence. Specifically, the study aimed to examine the potential mediation of perceived social support in this relationship. Based on the reviewed literature, it was hypothesized that perceived social support will mediate the relationship between attachment style and symptoms of PTS, such that higher levels of anxious and avoidant attachment will be associated with lower levels of perceived social support, which in turn will be associated with higher levels of PTS.

Research into factors contributing to the development of PTS among victims of sexual trauma carries significant practical implications. Despite the recognition that the type of therapy chosen for victims should be tailored to their individual characteristics (e.g., Cowan et al., 2020), therapeutic interventions often overlook the role of attachment. Nonetheless, as suggested by Mikulincer et al. (2015), offering experiences of security in therapy may help mitigate regulatory deficits in victims with insecure attachments, and facilitate better treatment outcomes. A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms that make people with insecure attachments more susceptible to PTS can help such therapeutic endeavors.

MethodParticipantsTwo hundred and twenty-six Israeli female survivors of sexual assault participated in the study. Their ages ranged from 18 to 57 years, with an average age of approximately 27 years (SD = 7.80). About half were single and the others were either married or in an intimate relationship, with most having no children. About half had an academic education, and most were employed. Approximately 42% identified as secular. The data are presented in Table 1.

Demographic and background characteristics of the participants.

The survey comprised typical socio-demographic questions, including gender, age, marital status, level of religiosity, and educational attainment. Additionally, it included inquiries tailored to the study cohort to collect data on experiences of SA, including the nature of the assault, timing, and assailant identity. These inquiries were adapted from Krebs et al. (2007) research on SA prevalence and characteristics before and during college and adjusted to fit the current research. The participants were also asked to indicate previous sexual traumas, as well as non-sexual traumatic experiences using Kessler et al. (1999) list of potentially traumatic life events.

Attachment styleAdult attachment orientation was assessed using the Experience in Close Relationship Scale—Short Form (ECR-SV; Wei et al., 2007). The ECL-SV consists of 12 items measuring adult attachment orientations, with responses rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The items are divided into two six-item subscales, one assessing anxious attachment (e.g., “I do not often worry about being abandoned”, reversed item) and the other assessing avoidant attachment (e.g., “I want to get close to other people, but I keep pulling back”). A higher score on the anxious attachment scale indicates a greater degree of anxious attachment. Similarly, a higher score on the avoidant attachment scale indicates a greater degree of avoidant attachment. Cronbach αs were .74 for attachment anxiety and .60 for attachment avoidance.

Perceived social supportThe Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al., 1988) was used. The MSPSS comprises 12 items designed to assess perceived social support from three sources: Family (e.g., “my family really tries to help me”), Friends (e.g., “I can talk about my problems with my friends”), and Significant Others (e.g., “there is a special person who is around when I am in need”). Participants rate each item on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). A higher total score indicates greater perceived social support. The MSPSS offers a nuanced perspective by capturing the intricacies and varied forms of support within social networks. Its comprehensive approach provides a holistic understanding of perceived social support as a multifaceted psychosocial construct (McCormick et al., 2023). Cronbach α was .92.

Post traumatic stress symptomsPost-traumatic stress symptoms (PTS) were measured using the PTSD Symptom Levels (PSL) questionnaire (Gil and colleagues 2015, 2016). The 20 self-report items are aligned with the 20 DSM5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD, comprising four clusters of symptoms: Intrusion, Avoidance, Negative alterations in cognition and mood, and Arousal (APA, 2013). With respect to the sexual violence they had endured, the participants were asked to rate the degree to which they were bothered by each symptom during the last month, from not at all (0) to extremely (4). Examples of items include: “Repeated, disturbing dreams of the traumatic experience” (Intrusion cluster), “avoiding memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the traumatic experience” (Avoidance cluster), “feeling distant or cut off from other people” (Negative alterations in cognition and mood cluster), and “having difficulty concentrating” (Arousal cluster). The internal consistency for the total score was α = .95, and it was used as the sum of the items (ranging 0-80).

ProcedureHebrew-validated versions of the above-mentioned measures were used. Initially, all questionnaires were adapted for online administration using Qualtrics software, facilitating the management and editing of studies. Data collection was conducted online via the software, enabling participants to respond anonymously at their convenience.

The study commenced following approval from the University's ethics committee. Information about the study was disseminated through designated online social networks and discussion groups targeting women who had experienced sexual trauma. Additionally, informational leaflets about the study were distributed at bus stations, public areas, and universities. We stated that we were seeking women who had undergone sexual violence in their adult lives to participate in a study on coping with sexual violence. We further noted that our goal was to enrich existing knowledge and that we were hoping that the findings of the study could be of help in the treatment of sexual assault victims. A link to access the research questionnaire was provided.

Upon accessing the provided link, participants were presented with a consent form detailing the study's purpose and their rights. The participants were assured of anonymity and that their responses would be used solely for research purposes. They were also made aware that they could decline participation and withdraw at any stage. Considering the sensitivity of trauma research, at the end of the questionnaire, information about aid organizations for women who have been sexually assaulted and emergency phone numbers where the participants could be helped was added.

Data analysisData was analyzed with SPSS version 29 and AMOS version 29. Descriptive statistics were used for the demographic and background characteristics, and Cronbach's α was used for the internal consistencies. As the variables of age and life events were positively skewed (skewness = 1.78 and 1.54, SE =.16, respectively) they were log-transformed. The study variables were described with means and standard deviations, and Pearson correlations were calculated between them. The associations between the demographic and background variables and the study variables were examined with Pearson correlations and t-tests. The study model was examined with path analysis, using Chi-square, Cmin/df, NFI, NNFI, CFI, and RMSEA as fit measures. Age, level of education, previous assault, and the number of previous life events, were controlled for. Control variables were allowed to correlate among themselves, and so were the two independent variables. Variables were standardized. Mediation was examined within the path analysis, with bootstrapping of 5000 samples and a bias-corrected 95% confidence interval.

ResultsTable 2 summarizes the characteristics of SA. The participants reported that assaults occurred approximately 6.31 years ago (SD = 6.62) when they were, on average, about 20 years old (SD = 4.73). In most cases (about 78%), the SA involved touches of a sexual nature, while vaginal sex was reported in about 25% of cases, and oral sex in approximately 14%. In most cases, there was one perpetrator (about 86%), known to the victim (about 69%), charges were not pressed, and treatment was not requested by the victim. Physical injury occurred in approximately 13% of cases. Nearly 60% of the victims reported prior experiences of SA (M = 14.51 years, SD = 4.84).

Characteristics of sexual assault.

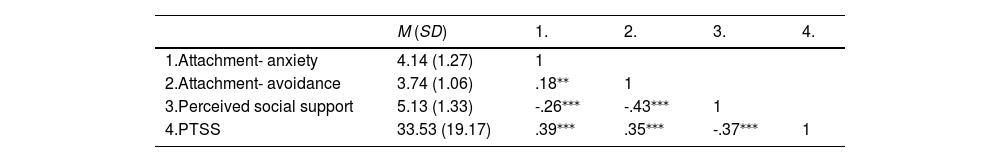

The mean score for post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) was approximately at the mid-point of the scale, with around 50% of the participants classified within the clinical range for PTSD (n = 114, 50.4%, cut-off point at ≥ 33) (see Table 3). Significant correlations were found between the study variables. Higher attachment anxiety and avoidance were associated with lower perceived social support, and both higher attachment anxiety and avoidance, as well as lower perceived social support, were associated with increased PTSS.

Several demographic and background characteristics were associated with PTSS. Firstly, women with an academic level of education had lower PTSS scores (M = 29.27, SD = 19.18) than women with lower levels of education (M = 37.63, SD = 18.32) (t(224) = 3.35, p < .001, d = .45). Secondly, women who had been victims of previous SA showed higher levels of PTSS (M = 37.63, SD = 18.55) than women who had not experienced previous SA (M = 27.54, SD = 18.57) (t(224) = 4.02, p < .001, d = .54). The number of previous life events was also positively associated with PTSS (r = .33, p < .001). In light of these associations, level of education (1-academic, 0-lower than academic), previous SA (1-yes, 0-no), and the number of previous life events were controlled for when examining the study hypothesis. Due to its wide range, age was controlled for as well, despite its non-significant relationship with PTSS. It should be noted that the highest correlation between the control variables was r = .41 (p < .001), and max VIF was 1.40, so no collinearity was detected.

The study model was examined with path analysis, using attachment styles as independent variables, perceived social support as the mediator, and PTSS as the dependent variable. Age, level of education, previous assault, and the number of previous life events, were controlled for. The two attachment styles were correlated. Mediation was examined within the path analysis, with bootstrapping of 5000 samples and a bias-corrected 95% confidence interval. The model was found to have good fit values: χ2(10) = 13.33, p = .206, Cmin/df = 1.33, NFI = .952, TLI = .962, CFI = .987, RMSEA = .039, and is shown in Fig. 1 and Table 4. Results demonstrate that both mediation paths were supported. Higher attachment anxiety and avoidance were associated with lower perceived social support, which in turn was associated with increased PTSS.

Direct and indirect associations between attachment styles, perceived social support, and PTSS.

Note. DV = dependent variable, IV = independent variable, R2 = percent of explained variance

As may be observed in Fig. 1 and Table 4, both the direct associations between attachment styles and PTSS and the indirect associations between them, are significant. That is, mediation is partial. Analysis of the proportion mediated revealed that 9.0% of the association between attachment anxiety and PTSS, and 25.9% of the association between attachment avoidance and PTSS, were mediated. That is, most of both associations are direct, yet a greater proportion of the mediated relationship corresponds with attachment avoidance than with attachment anxiety. Comparing the coefficients for the associations between attachment styles and perceived social support (β = -.19 vs. β = -.39), revealed that the association with attachment avoidance was indeed stronger (t(225) = 2.37, p = .019), and thus that the mediated effect is stronger than that of attachment anxiety. Comparing the coefficients for the direct associations between attachment styles and PTSS (β = .33 vs. β = .20), revealed no significant difference between them (t(225) = 1.55, p = .123). Thus, the mediated association was stronger for attachment avoidance, while no difference was found between the two attachment styles, regarding the direct association with PTSS. All in all, most of the association was direct rather than mediated.

DiscussionThe present study investigated the interrelations between attachment style, perceived social support, and PTS associated with adult sexual trauma. Specifically, we aimed to assess the potential mediation of perceived social support in the relation between attachment styles and PTS. The results confirmed the anticipated pattern, showing positive correlations between insecure attachments and PTS, as well as negative correlations with perceived social support. The mediation analysis revealed both significant direct and indirect associations, indicating partial mediation.

The direct associations between attachment styles and PTS suggest that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance independently contribute to the development and maintenance of PTS. Early-life experiences with attachment figures shape adult cognitions and emotion regulation, potentially increasing susceptibility to PTS following trauma (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). The links between attachment insecurities and PTS are in accordance with findings from previous studies on different types of traumas (e.g., Marshall & Frazier, 2019; Orme et al., 2021), including childhood sexual trauma (Ensink et al., 2021; Spencer et al., 2021). The present findings add empirical evidence to current knowledge, showing that insecure attachments are associated with PTS following adult sexual trauma.

The findings additionally support the notion that both the anxious and the avoidant insecure attachment styles are linked with PTS. While anxious attachment has been consistently found to be a strong risk factor for PTS, results regarding avoidant attachment are mixed (Woodhouse et al., 2015). It was suggested that avoidant attachment may potentially mitigate heightened levels of PTS, due to employing defensive strategies and cognitive processes. The results of the present study indicate that similar to anxious attachment, avoidant attachment is also associated with an increased risk of PTS.

As expected, attachment styles were associated with the perception of social support, underscoring the link between attachment and interpersonal dynamics, consistent with Mikulincer and Shaver's (2007) adult attachment theory. Individuals rely on their environment in different ways, dependent upon their attachment style. Insecurely attached adults withdraw from their environment (avoidant attachment) or overly and excessively seek proximity to others around them (anxious attachment). Both patterns of behavior are ineffective in coping. On the other hand, securely attached individuals adaptively seek and rely on support (Mikulincer et al., 2015).

The present study relied on the strong link between social support and mental health, particularly the development of PTS (Zalta et al., 2021). Perception of social support reflects the individual's capacity to benefit from close relationships with others in times of need, which enhances resilience. The findings of the present study are consistent with previous research, indicating a significant relationship between perceived social support and PTS among SA survivors. The partial mediation found suggests that perceived social support may serve as a mechanism linking attachment insecurity to PTS. Notably, in this relationship social support appears to have a more significant role for avoidantly attached SA survivors compared to anxiously attached survivors.

The practical implications of the results relate to the treatment of female victims of sexual trauma. Targeted, personalized treatments for victims are recommended to achieve beneficial results (Cowan et al., 2020; Nixon, 2024). The present results underscore the significance of attachment in addressing PTS resulting from adult sexual trauma. Early-life experiences with attachment figures shape adult cognitions and emotion regulation, potentially increasing susceptibility to PTS following trauma. Therapeutic interventions that address these aspects may benefit victims. More specifically, internalized models of attachment figures influence adult perceptions of others, feelings toward them, and motivations for social connection. Attachment-focused interventions aimed at enhancing the capacity to positively perceive and utilize social support may be beneficial, particularly for patients with an avoidant attachment style.

Attachment-focused therapy may be especially relevant for SA survivors. Victims of sexual trauma frequently experience self-criticism for placing trust in others and subsequently being harmed by them. They may grapple with feelings of guilt and shame, leading them to conceal the trauma and cope with it in isolation (Gueta et al., 2020; Idisis & Edoute, 2017). These tendencies may be particularly pronounced when coupled with an insecure attachment style, particularly an avoidant one. Engaging in attachment-focused therapy to foster trust and security could prove beneficial. The extremely high rates of PTS associated with sexual trauma, also evidenced in the present study where up to 50% of the women met the definition of a clinical diagnosis of PTSD, render effective treatments especially needed.

LimitationsThe main limitations of the present study stem from its retrospective design and dependence on self-report measures. Biases associated with memory recall, subjectivity, and social desirability may have influenced the data collected. While these limitations are pertinent to reporting various types of traumas, reporting sexual traumas may be particularly challenging and susceptible to bias. The study was voluntary, potentially leading to selective participation if women who felt comfortable sharing their experiences were more likely to participate compared to those who found it difficult to do so. However, the research procedure, which involved anonymous online responses, without the need for identification and at a time and place convenient for the participant, may have helped mitigate concerns related to disclosing the trauma, to some extent.

Another limitation concerns the cross-sectional nature of the study, which prevents the establishment of causality and directionality of the relationships found. On top of that is the low internal consistency of the avoidant attachment scale, which might have biased the results. For example, as the attachment patterns of the participants were not assessed prior to their experiences of sexual traumas, the potential impact of the traumas on attachment cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, it cannot be definitively established that insecure attachment predicts low social support; the relationship may also be reversed. Investigations employing longitudinal designs can help elucidate the directionality of these relationships.

Conclusions and future researchPerception of social support as an explanatory mechanism linking adult attachment styles to PTS has been understudied (Besser & Neria, 2012; Jittayuthd & Karl, 2022; Shallcross et al., 2014; Volgin & Bates, 2016), and as far as is known has not been investigated in the context of sexual trauma. Further research is warranted to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms linking adult attachments to PTS following sexual trauma. Future studies should deepen the understanding of specific mechanisms through which attachment insecurity may contribute to PTS, such as the role of cognitions (e.g., negative working models of self and others) and emotions (e.g., feelings of loneliness, rejection, and strategies of affect regulation) (Mikulincer et al., 2015). Testing the efficacy of attachment-focused interventions in enhancing social support and reducing PTS among victims of SA can provide evidence for best practices in clinical settings.

Factors associated with the social environment should also be considered. For instance, in more conservative societies, victims may perceive lower social support, due to greater fear of social criticism and stigma. The way victims perceive the legal and social remedies available to them may also have an effect. For example, knowledge and understanding of the law and available rehabilitation and treatment options can influence how victims perceive their social resources and society in general. These factors may interact with the victims’ attachment style to have a combined effect on the development of PTS. Future studies may benefit from exploring the effect of these factors on the perception of social support and PTS among SA survivors.

Finally, it should be considered that factors associated with the social environment could also be associated with victims’ reluctance to report SA to the police. It has long been recognized that the majority of SA cases remain unreported (e.g., Zvi, 2022a,b), as supported by the participant's reports in the present study, where over 90% didn't report the assault. As such, addressing the aforementioned factors may benefit not only treatment and support strategies for victims but also initiatives aimed at improving reporting rates and enhancing the effectiveness of legal and social responses to SA.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approvalThe study was approved by the Ethics committee of the university [AU-SOC-LZ-20221019]