Diabetes self-management (DSM) is essential for patients to achieve better health outcomes. However, previous studies have demonstrated that the performance of DSM is not optimal. This study was designed to identify the significant determinants of self-management behavior in type 2 diabetes(T2DM) patients to improve DSM.

MethodA convenient sampling method was employed in this study. Data were collected from a community health center from January to February 2021 in Nanjing city, China. A total of 431 patients completed the self-administered questionnaires. A structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior(TPB) was adopted for analysis.

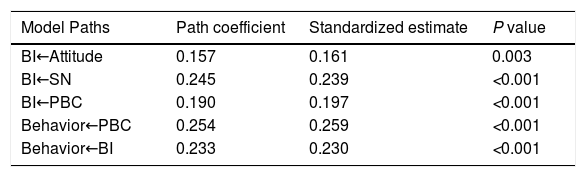

ResultsTPB model presents excellent goodness of fit of data. Attitude (β=0.161, P < 0.01), subjective norms (SN) (β=0.239, P < 0.001), and perceived behavior control (PBC) (β=0.197, P < 0.001) were strong predictors of intention. Intention (β=0.230, P < 0.001) and PBC (β=0.259, P < 0.001) had a direct effect on self-management behavior. The impact of attitude and SN on behavior was significantly mediated via behavioral intention.

ConclusionThe application of TPB to self-management behavior in T2DM patients can significantly enhance our understanding of theory-based self-management behavior. This predictive model could potentially be a valuable tool and provide a feasible approach for formulating more targeted and population-specific DSM interventions in future research.

Diabetes is one of the most acute chronic non-communicable diseases in the world. In recent years, with the increase in prevalence, the health expenditures related to diabetes present a substantial social, financial, and healthcare system burden across the world, and its complications have seriously affected the quality of life (Xu et al., 2013). The IDF Diabetes Atlas showed that, in 2019, the number of diabetes patients had increased to 463 million globally (Saeedi et al., 2019). China is among the worst affected countries, with the number of diabetes patients growing sharply in recent years. The number of diabetes patients in China reached 140.9 million in 2021, and it is predicted that this figure will reach 174.4 million by 2045(Sun et al., 2021). Diabetes caused 830,000 deaths in China in 2019. The progression of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and its potentially severe complications can lead to a decline in quality of life and an increased financial and psychological burden on patients(Chatterjee et al., 2017). Increases in health expenditure were driven by population growth, as well as increasing urbanization and lifestyle changes. The national cost of diabetes in China in 2021 was estimated at around $165.3 billion, up from $51 billion in 2015(IDF, 2021). T2DM is increasingly recognized as a serious, worldwide public health concern. Diabetes prevention and control have become an urgent public health issue requiring attention and research.

T2DM is a chronic, lifelong disease that cannot be cured but is entirely manageable. The most effective way to prevent and control diabetes is through health promotion and behavioral intervention (Wang et al., 2012). Diabetes self-management (DSM) is recommended for all individuals with diabetes to manage acute complications prevention, long-term complications reduction, and glycemic control (ADA, 2019; Society, 2021). DSM refers to the ability of individuals to manage their behaviors effectively over long periods, such as diet modification, physical activity, foot care, adherence to medication or insulin injection as prescribed by doctors, and self-monitoring of blood glucose (Powers et al., 2017). Recent literature indicates that self-management offers benefits to individuals with diabetes, which is the key to reducing glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), delaying acute and chronic complications, and improving quality of life (Barlow et al., 2002; Chrvala et al., 2016; Ji et al., 2014). Ding et al. found that self-management could effectively improve the cognitive level, self-management ability, and self-efficacy of diabetes patients and fully mobilize the subjective consciousness of patients, which is the most cost-effective measure of diabetes management (Ding et al., 2014).

However, many patients with T2DM have not complied with the recommended self-management activities (Gonzalez et al., 2016). A recent study found a low level of self-management behavior. Only 1% of patients monitored blood glucose, 9.5% engaged in physical exercise regularly, and 18% followed the recommended diet (Alrahbi, 2014). A previous study stated that the level of DSM in patients had improved slightly compared to similar studies, but it is still not ideal (Sun et al., 2011). Another study found that self-management diabetes in China remains low (Zhao et al., 2015). Although these studies have indicated that T2DM patients are less likely to adhere to self-management, the underlying reasons for non-adherence have not explicitly been examined. A comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the psychosocial factors can promote self-management and health outcomes in patients with diabetes (Thoolen et al., 2008). In addition, the linking of psychosocial factors to self-management is complex and requires a relevant theoretical model to understand its mechanisms of action. Consequently, it is of great significance to determine the main factors affecting the self-management behavior of T2DM patients by a theory-driven study in order to provide guidance for implementing more targeted intervention measures for this population.

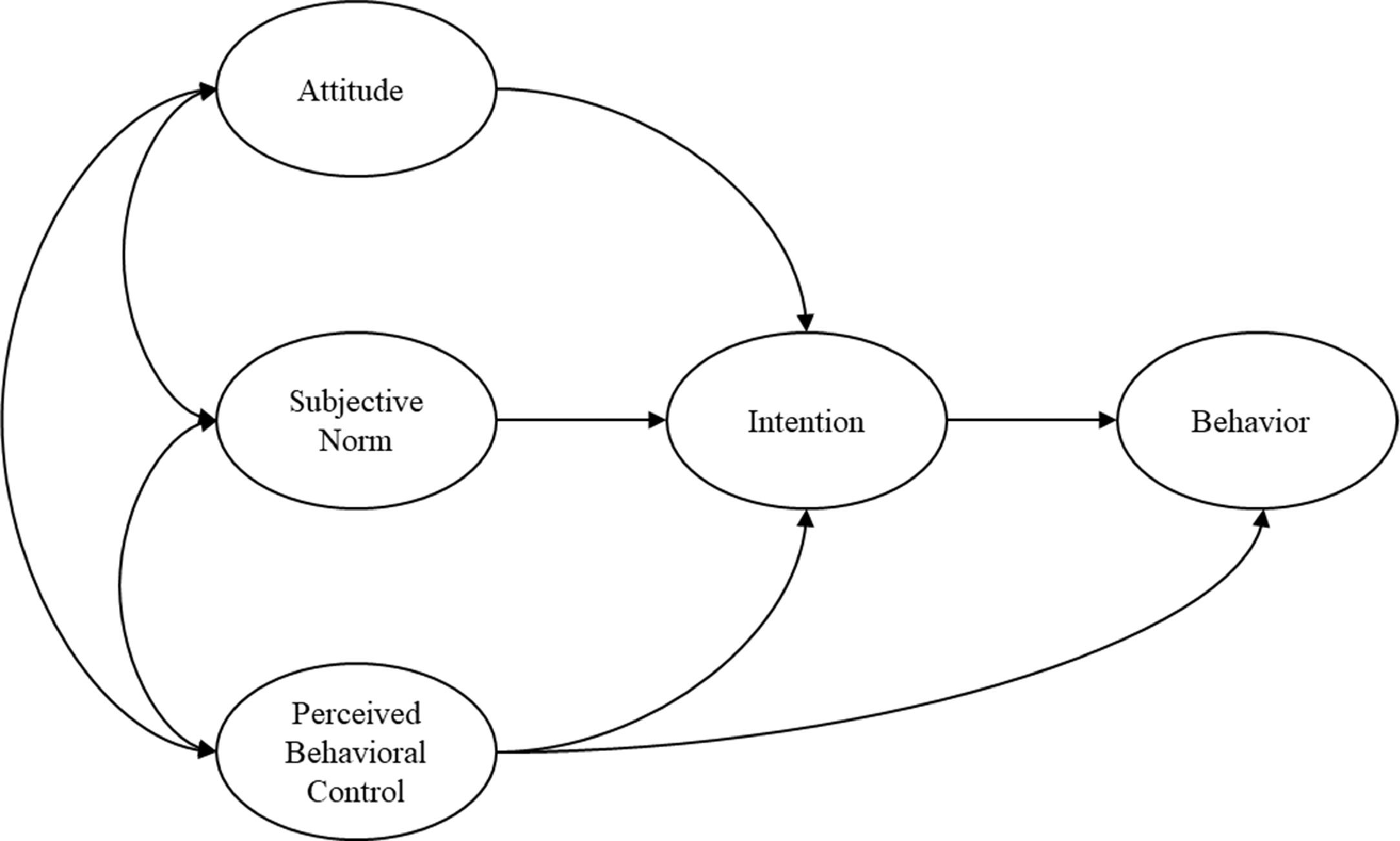

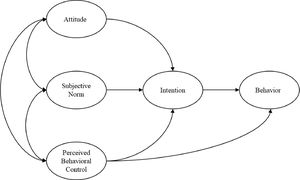

Theoretical frameworkThe theoretical framework for this study was based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). TPB, an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action(TRA), is one of the most influential and popular conceptual frameworks for health-related behavior research, predicting and explaining specific behaviors (Ajzen, 1991). Initially developed by Ajzen, it is essentially a social cognitive theory used to explore the factors related to behaviors, predict behavioral intentions, and explain how people perform decision-making (Ajzen, 1985). TPB posits that an individual's behavior is affected by behavioral attitude (BA), subjective norms (SN), perceived behavioral control (PBC), and behavioral intention (BI). The theoretical framework diagram of the TPB model is shown in Fig. 1. Emerging research has applied the TPB to identify determinants of self-management behavior among patients with T2DM. Surveys such as that conducted by Tomoe have shown that TPB predicts a low-glycemic diet management behavior in patients with T2DM (Watanabe et al., 2015). In addition, Boudreau and Godin also utilized the TPB to predict the leisure-time physical exercise behavior of T2DM patients (Boudreau & Godin, 2014).

Based on the TPB, multiple psychosocial factors affecting the self-management behavior of T2DM patients can be revealed, and the interaction between various factors can be clarified to identify the core influencing factors. Therefore, this study aims to identify the determinants and internal mechanism of self-management behavior in T2DM patients based on the TPB, which is a critical issue for developing diabetes health management measures and improving self-management behavior.

MethodsData source and samplingA convenient sampling method was conducted amongst individuals with T2DM at Community Healthcare Center in Jiangning District between January and February 2021, Nanjing. All participants from the sampled healthcare service center were invited to participate in the survey. Those who met the following criteria were included in this study: those diagnosed with T2DM (aged >18 years old); permanent residents in the Jiangning district; those with a health record in the community health service center; those without mental impairment, Alzheimer's disease, or other mental disorders and those who agreed to participate.

Data collectionThe recommended sample size for studies using the TPB framework should be greater than 160 participants (Francis et al., 2004). The sample size estimate was measured according to the criterion of 1:10 observations per indicator, and 5% of invalid questionnaires were taken into account (Wu, 2010). With 42 observed variables being obtained from the questionnaire, a minimum sample size of 420 was required. In this study, a total of 450 individuals with T2DM were selected using a convenient sampling strategy. Nineteen individuals were excluded from the study due to missing data (N = 19). Eventually, 431 responses were included, with an effective rate of 95.8%. Face-to-face questionnaire data collection was conducted by trained investigators (including general practitioners, nurses, and medicine postgraduates). Individuals were asked to fill in a series of questionnaires, including demographic data, disease-related data, and a self-administered questionnaire.

MeasuresThe questionnaire was designed based on the TPB. The questionnaire consists of five parts: Attitude, Subjective Norms, Perceived behavior control, behavioral intention, and actual self-management behavior (including Dietary modification, Physical exercise, Footcare, Medication adherence, Blood glucose and blood pressure self-monitoring, and Complication screening). According to guidelines for TPB surveys (Francis et al., 2004), measures of theory-based determinants for each variable were constructed.

Behavioral Attitude (BA) (5 items)The behavioral attitude was defined as assessing the likely or expected results (positive or negative) of performing self-management behavior in individuals. The more positive attitude towards the behavior, the stronger the individual's willingness to act. Measures of attitude ("Do you think it is important to adhere to diet therapy/physical exercise/ prescribed medication/self-monitor blood glucose/ receive health education?"). Respondents were asked to rate the degree of their beliefs on the importance of self-management behaviors on a five-point Likert scale, with a higher score indicating that the patients held a more positive view of the self-management behavior.

Subjective Norm (SN) (12 items)Subjective norms refer to an individual's perception of general social pressure to perform (or not perform) certain behaviors. Individuals are more (or less) likely to engage in self-management behavior if those important people approve (or disapprove) of the behavior. Measures of subjective norms (e.g., “To what extent does the view of doctors/families/friends impact your adherence to physical activity?”). Respondents were asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale, with a higher score indicating a more profound influence by those groups.

Perceived behavior control (PBC) (5 items)PBC refers to an individual's perception of behavioral control. PBC measures how easy or difficult a patient considers the performance of self-management behaviors. For example, measures of perceived behavior control (“For you, adherence to diet therapy/physical exercise/ prescribed medication/self-monitor blood glucose is…”. Respondents rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from " Very difficult " (1) to " Very easy "(5), with a higher score indicating the easier they found it to perform self-management behaviors.

Behavioral intentions (5 items)Behavioral intention indicates how much effort a patient can make to perform the self-management behavior. The stronger the intention to perform self-management behavior, the more likely it will be carried out. Measures of behavioral intention (“I intend to adhere to diet therapy/physical exercise/ prescribed medication/self-monitor blood sugar/check HbA1c.”). Respondents rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

Self-management behaviors (15 items)Self-management behavior was assessed by a six-category measure of how those diabetes patients behave from various aspects. Self-management behaviors were classified into six categories: (1) diet modification; (2) physical activity; (3) foot care; (4) medication adherence; (5) blood glucose and blood pressure self-monitoring; (6) Regular complications screening. Measures of self-management behavior (e.g., "Have you self-monitored for blood glucose according to doctors' recommendations over the past six months?"). Respondents were asked to respond to each survey statement by using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from " Never " (1) to " Always " (5).

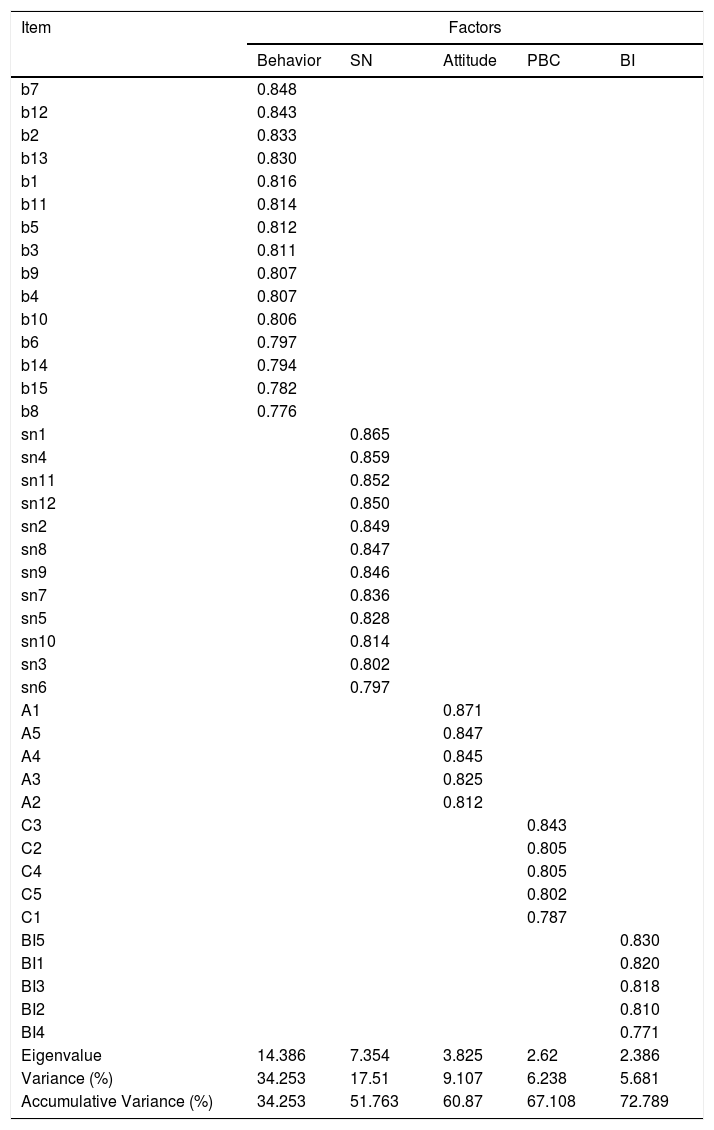

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value indicates 0.948, and Bartlett's test result was P < 0.001, suitable for factor analysis. Five factors were extracted, contributing to 72.789% of the sum of the squared loadings (Table 1). The Cronbach's alphas for each construct were as follows: attitude (0.913), subjective norm (0.963), perceived behavior control (0.914), intention (0.908), and self-management behavior (0.969). All the items are highly loaded on their constructs.

Exploratory factor analysis (n = 215).

PBC, perceived behavioral control; SN, subjective norm; BI, behavior intention.

All participants provided informed consent. Ethical approval, including the consent procedure, was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China, and confirmed that all methods were performed by relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistical analysisAll data were processed using SPSS 26.0(SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), Epidata 3.1, and AMOS 21.0(Amos Development Corporation). The characteristics of the participants were measured by frequency and percentage. Single-choice questions were measured by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to construct a measurement model between latent variables and observable indicators. A structural equation model (SEM) was constructed to identify effects between latent variables based on the TPB. The maximum likelihood (ML) method was used to estimate the parameters. Multiple indicators were used to evaluate the model's goodness of fit comprehensively.

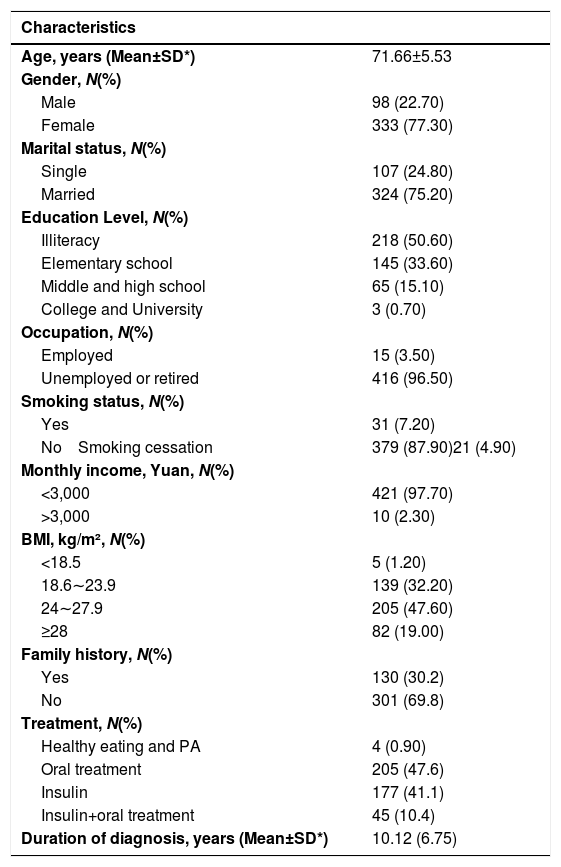

ResultsSociodemographic and socioeconomicTable 2 presents the participants' sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Four hundred fifty patients with T2DM were involved in this research, with 431 patients finally contained. The mean age (SD) of the 431 participants was 71.66 (5.53) years, and 77.3% of participants were female. Of all participants, only 1.2% had a BMI of less than 18.5, and the mean duration of having T2DM was 10.12 (6.75) years. Nearly three-quarters of the participants had been married (75.2%). However, only 2.3% of the participants earned more than 3000 Yuan (Chinese currency) in income per month.

General demographic characteristics of 431 Nanjing community-dwelling residents with T2DM.

Notes: *SD: Standard Deviation.

Yuan represents Chinese currency; Physical activity (PA).

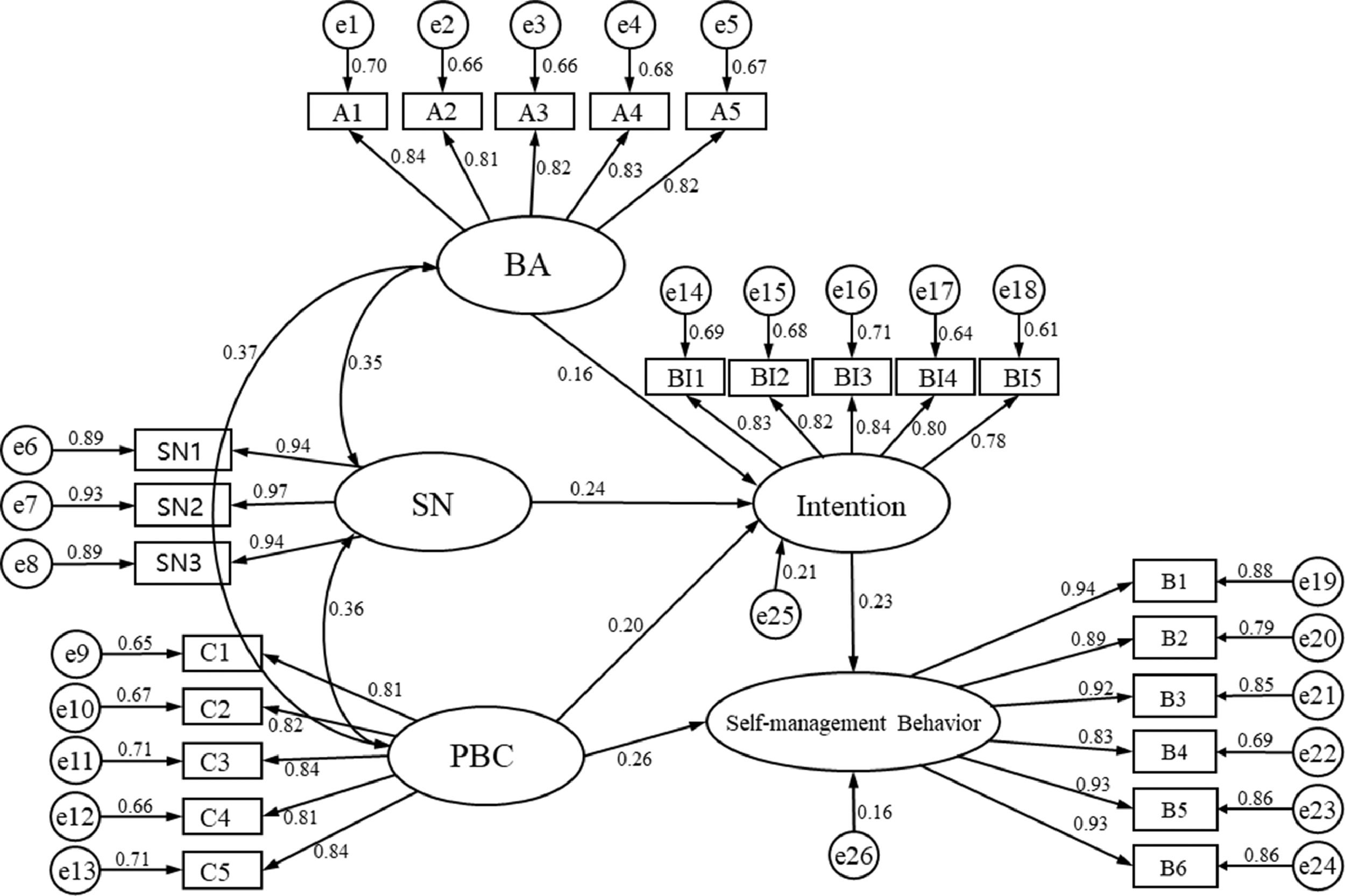

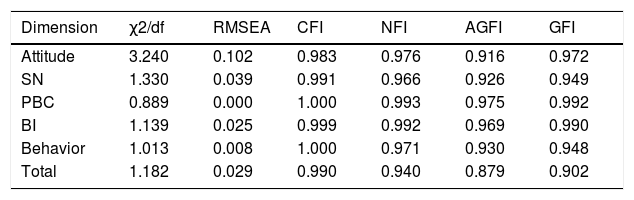

In this section, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the consistency between the five factors and the theoretical model. The goodness of fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) are shown to describe the goodness of fit of the model. The final results of the CFA indicated that the model fits samples well (χ2/df = 1.182, GFI = 0.902, AGFI=0.879, CFI = 0.990, NFI=0.940, RMSEA=0.029; see Table 4). Composite reliability (C.R.) and average variance extraction (AVE) were used to evaluate the convergent validity and discriminant validity of indicators. Generally, AVE value >0.5 and C.R. value >0.7 are recommended (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 1998). The AVE values of the five factors involved in this study (BA, SN, PBC, BI, self-management behavior) are all greater than 0.5, and CR values are all greater than 0.7, indicating that the data of this measurement scale has excellent convergent validity (Table 3). The results presented good reliability and validity of the scale.

Survey statements and categorical confirmatory factor analysis.

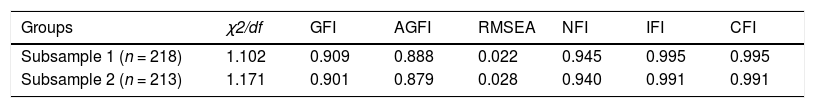

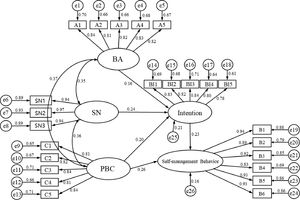

A structural equation model (SEM) is a statistical method to analyze the relationship between variables. SEM can evaluate the theoretical model according to the consistency of the relationship between the theoretical model and the actual data to solve practical problems. In this study, SEM was constructed based on the TPB to explore the relationship between latent variables. Two random subsamples were performed to test the fit of TPB in a structural equation model. The fitness of the two models is good (Table 5). The maximum likelihood estimation method was adopted to estimate the parameters. Path coefficient was determined to describe the relationship between five variables. Fig. 2 depicts the direct effects of the TPB model. Direct paths from attitudes, SN, and PBC on behavioral intention were statistically significant. As hypothesized by the TPB, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control were positively related to intention. Stronger attitudes (β=0.16, P < 0.01), subjective norm (β=0.24, P < 0.001), perceived behavior control (β=0.20, P < 0.001) were all linked to stronger intentions. Furthermore, a direct path between PBC and self-management behavior was found (β=0.26, P < 0.001). The stronger intention was linked to stronger self-management behavior (β =0.23, P < 0.001) (Table 6). The direct path between PBC and self-management indicates that the effect of perceived behavioral control on self-management was stronger than it was through intention.

The specific model fitting indicators have reached the corresponding requirements standard, indicating that the model fits well, as shown in Table 4. The standardized parameter estimating the final structural model is shown in Fig. 2. The model with behavioral intention, self-management behavior predicted by BA, SN, and PBC and showed a good fit to the data (χ2/df = 1.182, GFI = 0.902, AGFI=0.879, CFI = 0.990, NFI=0.940, RMSEA=0.029; see Table 4).

Goodness of fit of the models (n = 216).

AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index; CFI, comparative fit index; GFI, the goodness of fit index; NFI, normed fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; PBC, perceived behavioral control; SN, subjective norm; BI, behavior intention.

Goodness of fit of the models in two subsamples.

| Groups | χ2/df | GFI | AGFI | RMSEA | NFI | IFI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsample 1 (n = 218) | 1.102 | 0.909 | 0.888 | 0.022 | 0.945 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| Subsample 2 (n = 213) | 1.171 | 0.901 | 0.879 | 0.028 | 0.940 | 0.991 | 0.991 |

AGFI, adjusted goodness of fit index; CFI, comparative fit index; GFI, the goodness of fit index; NFI, normed fit index; PBC, perceived behavioral control; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SN, subjective norm; BI, behavior intention.

The path coefficient among variables and self-management behavior.

PBC, perceived behavioral control; SN, subjective norm; BI, behavior intention.

This study was carried out to explore the determinants of self-management behaviors among patients with T2DM based on the TPB. The TPB constructs were verified to have tremendous predictive ability for self-management intention and actual self-management behavior in patients with T2DM. We found that attitude, SN, and PBC were significant predictors of intention. Moreover, PBC and intention can directly predict self-management behavior, with PBC being the strongest predictor of self-management behavior.

Attitude towards DSMAttitudes toward behavior reflect an individual's overall positive or negative evaluation of a particular behavior. Generally speaking, the more positive the attitude towards specific behavior, the stronger the individual's willingness to perform the behavior. The current study found that a statistically significant association between attitude and self-management behavior was partly mediated through behavioral intention. The more positive attitude patients have, the more intention they will perform on diabetes self-management behavior. This finding is consistent with a previous study that attitude was the main predictor of intention in diabetes management of physical activity (Presseau et al., 2014). Also, a recent study has confirmed that knowledge and attitude directly correlate with practice and self-management to promote glycemic control (Karbalaeifar et al., 2016). Likewise, as reported in other studies, the determinants of attitude proved significant in modeling DSM in the physical activity domain (Boudreau & Godin, 2009).

Nevertheless, the path coefficient between attitude and intention is the lowest of the other two indicators. This result may be explained by the fact that most patients have low education levels. The results are in agreement with Karbalaeifar's (2016) findings which showed that higher knowledge was associated with higher attitude, better self-management behaviors, and lower HbA1c (Karbalaeifar et al., 2016). These results highlight the need to design and implement health education programs for people with T2DM to increase awareness of self-management behavior.

SN towards DSMSubjective norm refers to the individual's perception of other people's expectations of their behavior (Armitage & Conner, 2001). The most prominent finding to emerge from the analysis is that SN correlates highest with intention, which is also a strong predictor of intention. These results corroborate the previous study that SN was a better predictor of intention than attitude (Godin et al., 2005). The social support of patients with T2DM usually comes from doctors, family members, and friends. The underlying explanation is that participants have a more positive perception of self-management behavior, such as diet modification, physical exercise, and self-monitoring blood glucose, when doctors or family members expect them to comply (Xu et al., 2008). This finding aligns with previous studies that support from healthcare practitioners, family members, and friends has been considered vital for patients with T2DM since it enhances their motivation for self-management behavior (Bowen et al., 2015; Dao-Tran et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2008). Therefore, tailor-made, ongoing support of healthcare professionals, and the encouragement of family and friends are required to assist patients in removing barriers to DSM and ultimately changing their lifestyles.

PBC towards DSMPBC refers to people's perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest. The results of the current study suggest that PBC is the strongest predictor of self-management behavior, while intention came second. This finding emphasizes that PBC contributes to the prediction of DSM over and above the effect of intention. Several studies support the finding that PBC is the most critical factor in predicting intent to perform self-management behavior for individuals with T2DM and is also directly related to self-management behavior (Daryabeygi‐Khotbehsara et al., 2021; Gatt & Sammut, 2008). In keeping with the present results, a recent study has demonstrated that self-efficacy(similar to PBC) predicts patients’ adherence to DSM recommendations and is particularly significant for overall self-management (Abubakari et al., 2016). This finding indicates that this may be an essential factor that more considerations are required to have when assessing the possibility of performing recommended self-management behavior. Therefore, every attempt must be made to identify improving individuals’ perceived behavioral control concerning DSM.

Intention towards DSMBesides the PBC, behavioral intention also emerged as a significant essential predictor of self-management behavior. The behavioral intention was found to affect self-management behavior directly and significantly. Moreover, the intention was found to mediate the relationship between attitude, SN, and behavior. People who considered themselves to have the intention to perform self-management behaviors were more likely to engage in DSM. These results corroborate the findings of a great deal of the previous work in theory-based health behavior studies (Plotnikoff et al., 2010; Sarbazi et al., 2019).

ImplicationsThis study supported the usefulness of TPB and has substantial implications for engagement in self-management for patients with T2DM. The present study raises the possibility of developing individualized self-management programs, carrying out targeted health education and guidance according to the characteristics of community diabetes patients, and effectively improving the self-management level of patients.

Specifically, this study provides evidence that might be utilized by healthcare practitioners and researchers in implementing and evaluating appropriate DSM interventions based on the TPB. Our findings support that such interventions would need to focus on and promote the importance of SN and PBC with specific emphasis on the enhancement of strong intention and positive self-management behaviors. Family and friends can be helpful in encouraging patients to increase their consciousness to have a better lifestyle and comply with recommended DSM. Given that the PBC appears to be the most crucial predictor of the actual performance of self-management behavior in individuals with T2DM, healthcare professionals should pay attention to it during health education sessions with their patients. Further research should focus on identifying related factors, including the individual's perception of the extent of required lifestyle changes and the effort required to implement them.

LimitationsThis study must be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, participants were all from one community healthcare center. Thus, we ignore the extent to which it represents the general population. Additionally, participants included were mainly female (77.3%), elderly [(71.7±5.5) years old], and relatively low educational level (33.6% of elementary school). Therefore, the research results may not represent all diabetes patients. For this reason, future research should include diverse populations and enlarge the sample size.

ConclusionThis study offers insight into DSM among patients with T2DM as well as significant factors that are associated with self-management behaviors on the basis of TPB. A theory-driven model is suitable for Chinese people with T2DM to assess self-management behavior and make tailored recommendations for lifestyle modifications based on individual behavioral determinants. TPB model could guide patients with T2DM self-management behavior as PBC and behavioral intention were strong predictors. Accordingly, this article believes that the TPB could be applied to intervene in the self-management behavior of type 2 T2DM patients so as to improve their quality of life and delay the development of diabetes progress. This theory-based model potentially offers a feasible approach to study and formulate more focused and population-specific DSM interventions for future research.

Data availability statementThe datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

FundingThis research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.71503139), Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD) and Top-notch Academic Programs Project of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions(TAPP, Grant No. PPZY2015A067). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statementLihua Pan: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Xia Zhang: Validation. Sizhe Wang: Validation. Nan Zhao: Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Ran Zhao: Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Bogui Ding: Resources. Ying Li: Resources. Wenxue Miao: Resources. Hong Fan: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the staff in Fangshan Community Health Service Center in China in conducting the survey.