Bystander behaviors can be an important key for preventing all forms of violence against women. Identifying their facilitators and barriers becomes a priority. The aim of this research is to analyze the impact of the previous experiences of women (as sexual harassment victim or bystander) on their perceived responsibility to intervene as bystander in a case of workplace sexual harassment and to determine the possible mediating role of certain attitudinal and evaluative factors.

MethodA non-probability convenience sample of 633 Spanish women answered a sociodemographic data questionnaire, a victimization questionnaire designed ad hoc, and the Questionnaire of Intention to Help in VAW Cases.

ResultsThe results obtained indicate that previous victimization experiences as a victim or witness of sexual harassment impact the responsibility to intervene, mediated by the acceptance of sexual harassment myths and the perceived severity of workplace sexual harassment.

ConclusionsThese results may help to understand how to design prevention programs and which key variables to incorporate.

Bystander behaviors can be an important key for preventing all forms of violence against women (VAW) (Lyons et al., 2022a; Kettrey & Marx, 2021; McDonald et al., 2016; McMahon & Banyard, 2012; Mujal et al., 2021) and, consequently, identifying the factors that facilitate these behaviors and the barriers that prevent it from becoming a priority. In this context, our research aim is to analyze the impact of some of these factors on sexual harassment (SH) in the workplace, a particular form of VAW. Specifically, we will analyze the impact of the previous experiences of women (as SH victim or bystander) on their perceived responsibility to intervene as bystander in a case of SH and determine the possible mediating role of certain attitudinal (i.e., myths about SH) and evaluative (i.e., the perceived severity of SH) factors.

As Fitzgerald and Cortina (2018) highlight, the increasing interest and research in SH shows that its parameters are broader and more pervasive than originally thought. Many definitions reflect the broader understanding of this violence. Academically, McDonald (2012) defines SH as a “conduct as unwanted or unwelcome, and which has the purpose or effect of being intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive” (p. 2), and Fitzgerald and Cortina (2018) indicate that “unwanted sexual attention” means: “sexual advances that are uninvited, unwanted, and unreciprocated by the recipient. These include verbal and physical behaviors, like sexually suggestive comments and compliments, attempts to establish sexual or romantic relationships, and unwanted touching” (p. 216).

Despite this complexity, given the impossibility of addressing all forms of harassment (sexual coercion, street sexual harassment, stalking by strangers or by intimate partner, unwanted sexual attention, etc.) in one study, we have limited the present research to the classic issue of SH in the workplace.

It should be noted that SH can be experienced by men or gender-diverse people, but SH is more often committed by men and suffered by women (Berdhal, 2007; Fitzgerald & Cortina, 2018; Lyons et al., 2022b; Pina et al., 2009). Thus this research starts from the premise that SH in general, and in the workplace in particular, is a form of sexual violence and a women's issue (Anon., GOGBV, 2022a; Fitzgerald & Cortina, 2018; Pina et al., 2009). Particularly, we conceptualize it as a form of VAW as defined by the Anon., CEDAW (1992): “violence which is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately”.

In fact, although samples, definitions and methods vary considerably, major prevalence studies suggest that one in two women has experienced some form of SH or unwanted sexual advances during her working life (Fitzgerald & Cortina, 2018; Ilies et al., 2006; Pina et al., 2009). In Spain, where our research was conducted, the latest survey data indicate that between 17.3 % and 28.4 % of women who were or are in the workplace have experienced SH at some point in their working life (DGVG, 2019; Anon., GOGBV, 2022b).

In VAW, and also in SH, bystanders (individuals who see or hear violent incidents and may intervene to protect or reduce harm to the victim) can play a crucial role in intervening before, during, or after the harassment takes place (Lyons et al., 2022a; McMahon & Banyard, 2012), for which reason the focus of prevention programs has shifted to the role of bystander intervention (Campbell & McFadyen, 2017; Fitzgerald & Cortina, 2018; Kettrey & Marx, 2021; McMahon & Banyard, 2012).

A highly relevant issue related to bystander intervention involves understanding the factors that facilitate or hinder their reaction. In this sense, it may be remembered that the situational model of bystander behavior (Latane & Darley, 1970) proposed five steps for bystander intervention in emergencies: notice the event, interpret the situation, take responsibility, decide to act, and act. From this model, Burn (2009) suggested five barriers to bystander inaction in sexual assault situations (i.e., failure to notice, failure to identify risk, failure to take responsibility, skills deficits and audience inhibition) identifying several situational and intra or inter-personal bystander factors that could hinder interventions at each barrier.

Recently, different systematic reviews have been centered in the analysis of these factors. For instance, Mujal et al. (2021) revised bystander interventions for the prevention of sexual violence, Park and Kim (2023) revised interventions in intimate partner violence and sexual assault, and Mainwaring et al. (2023) explored variables related to bystander intervention in sexual violence contexts. Few research studies analyze these barriers and facilitators in SH (e.g. Brewer et al., 2024; Lyons et al., 2022a, 2022b; McDonald et al., 2016).

As Park and Kim (2023) pointed out, many contextual components affect bystander intentions and behaviors, although some of them were not included in the situational model. In this sense, some theoretical models suggest that bystander involvement in SH is driven by workplace culture and the level of SH tolerance (McMahon & Banyard, 2012). In fact, several contextual features influence bystander intervention, including identification with and similarity to target, experience and anticipation of sanctions, workplace norms, and inaction or co-participation of others (McDonald et al., 2016). And, in this sense, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission encourages bystander training in terms of how to recognize and report the problem to make SH a “sense of collective responsibility” (Campbell & McFadyen, 2017).

But this research focused specifically on one barrier suggested by Burn (2009): failure to take responsibility, alongside some related factors. Particularly, following the classification proposed by Mainwaring et al. (2023), we will consider some individual variables (feelings of responsibility to intervene, rape myth attitudes, and previous victimization) and some situational variables (perceived severity of the sexually violent behavior and presence of other bystanders, with the latter serving only as a control condition).

Impact of previous victimization experiences of SH on the responsibility to interveneAs Mainwaring et al. (2023) observed, the relationship between a bystander's previous victimization experience in violence contexts and their intervention is not completely consistent. Some studies have shown no impact (e.g. Jacobson & Eaton, 2018; Reynolds-Tylus et al., 2019), while others have found various relationship directions. For example, some results pointed out that a previous history of victimization increased bystander response due to increased empathy for victims and responsibility to intervene; that is, a bystander with personal experience of violence would be more inclined to intervene in assault scenarios (e.g., Banyard & Moynihan, 2011; Bennett et al., 2014; Casey et al., 2017; Gidycz et al., 2006; Woods et al., 2016). In contrast, other results showed that a bystander with previous victimization experience may be less likely to notice a risky situation and to identify the situation as dangerous (e.g., Kistler et al., 2022). These different results suggest that this impact may be mediated by other variables such as whether past experiences have had positive or negative results (Mainwaring et al., 2023). Given the high prevalence of VAW victimization (Sardinha et al., 2022), it seems that this relationship between previous victimization experience of SH and the bystander responsibility to intervene requires further investigation, and we will explore it in this research (see hypothesis 1).

Regarding the responsibility to intervene, as identified in the systematic review conducted by Mainwaring et al. (2023), bystanders are more likely to act when they feel greater responsibility to intervene (Arbeit, 2018; Katz et al., 2015; McDonald et al., 2016), and bystanders who have not intervened when they could have, positioned themselves as outsiders to the incident, shifting the responsibility to others (Lamb & Attwell, 2019). Indeed, as Lyons et al. (2022a) highlight, some empirical research (i.e. Hoxmeier et al., 2020) indicates that the reason reported by a large proportion of bystanders who did not intervene was that the incidents are “none of their business”. Such a lack of personal responsibility could be influenced by factors including the moral perceptions of the victim, diffusion of responsibility, or individual characteristics of the bystander (Bennett et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2020; Yule et al., 2020).

One of the factors that can influence and result in this failure to take responsibility for intervening are rape or SH myth acceptance (Lyons et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2024; Martini & De Piccoli, 2020; Yule et al., 2020). Particularly, the acceptance of these myths can be related to a reluctance to intervene and help victims of harassment (Banyard & Moynihan, 2011; Bennett et al., 2014; Zelin et al., 2019).

Among rape and SH myths are beliefs that deny the scope of the problem (Bohner et al., 2022; Expósito et al., 2014; Megías et al., 2011). Accepting such beliefs may lead observers to fail to identify situations as high risk (Lyons et al., 2022a, 2024; Yule et al., 2020), or to minimize the perceived importance of violent incidents (Arbeit, 2018; McDonald et al., 2016) thus potentially reducing the responsibility to intervene (Lee et al., 2019). In fact, bystanders are more likely to intervene when they perceive that sexual violence is of greater severity (Jacobson & Eaton, 2018; Lyons et al., 2022b), perceive an evident and immediate danger to the victim (Oesterle et al., 2018), or identify that the perpetrator behavior crosses a certain threshold or increases (Mainwaring et al., 2023).

Moreover, among the myths about sexual violence and SH is the belief in the woman's responsibility, which attributes the responsibility for controlling SH to the victim, suggesting that female victims are guilty because of their failure to discourage men's advances (Lonsway et al., 2008). This myth is indeed widespread, as in recent research analyzing the Spanish social perception of sexual violence (Anon., GOGBV, 2018) in which 40.9 % of men and 33.4 % of women considered to some extent that responsibility for controlling SH at work lies with the harassed woman, as she is thought to be responsible for controlling the SH. And blaming the victims has consequences, including having lower empathy for them (Leone et al., 2020; Lyons et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2024; Martini & De Piccoli, 2020), and dismissing bystander responsibility to intervene (Lee et al., 2019).

Given these results, we will explore the relationship between the acceptance of SH myths, the perceived severity of SH, and the responsibility to intervene in a hypothetical scenario of SH (see hypothesis 2).

However, as Bennett et al. (2015) pointed out, any bystander intervention for situations involving sexual violence is complex and, consequently, research should further extrapolate the moderating effects among the intervening variables that may be facilitators or barriers to the bystander responses. In this regard, and similar to recent Spanish research on the mediation between perceived severity, myth acceptance and willingness or responsibility to intervene in other types of VAW, such us intimate partner violence against women (see Badenes-Sastre et al., 2023; Leon et al., 2022; Martínez-Fernández et al., 2021; Serrano-Montilla et al., 2023), we consider it pertinent to conduct an exploratory analysis of the combined role of previous experiences of victimization, SH myth acceptance, and perceived severity on the responsibility to intervene in an effort to improve future bystander interventions (see hypothesis 3).

Considering these previous findings, our aim was to analyze the impact of women's previous experience as victims or bystanders of SH on their perceived responsibility to intervene as bystander regarding this VAW form, determining the impact of myths and perceived severity of SH (evaluated in relation to a specific scenario) as a mediator's factors. Specifically, considering the available evidence, we hypothesize that: (1) Having been a victim (hypothesis 1.1.) or witness (hypothesis 1.2) increases the responsibility to intervene in a hypothetical scenario of SH (greater in victims than in witnesses); (2) Greater acceptance of SH myths and less perceived severity of this VAW will be related to less self-responsibility to intervene in a hypothetical scenario of SH; and (3) The influence of having been a victim/witness in the responsibility to intervene in a hypothetical scenario of SH was mediated by the acceptance of SH myths and the perceived severity of this VAW. Specifically, we expect past victimization experiences to be associated with a higher responsibility to intervene (especially in previous victims), and this direct relation will be mediated through lower acceptance of SH myths and greater perceived severity of the situation.

Although not all studies report differences between males and females in the likelihood to intervene as bystander (Mainwaring et al., 2023), gender is an important variable to consider because it could influence our analyzed variables (Lyons et al., 2024). For instance, usually, women have lower rape myths and higher intentions to intervene as bystander than men do (Kania & Cale, 2021; Labhardt et al., 2017). Despite this, we chose to study a sample composed only of women, as our objective includes analyzing experiences of victimization, and as already mentioned, prevalence of SH among women is significantly higher.

Finally, it could be noted that although mentions of the bystander effect (Darley & Latané, 1968) are common in the literature on the topic, empirical research has inconsistently supported the impact of the presence of other people on the bystander response (Mainwaring et al., 2023). Thus, the evidence is inconclusive and while in some studies the presence of other bystanders inhibits action (e.g., Katz, 2015), in others it encourages intervention (Katz et al., 2015). These inconsistent results may be due to the influence of other variables such as audience inhibition (Burn, 2009; Katz et al., 2015), or feelings of safety (Oesterle et al., 2018). Given these inconsistencies, we decided to control this bystander effect variable in order to isolate the effects of the main variables of our study, according to our objectives and hypothesis.

Material and methodsParticipantsA non-probability convenience sample of 633 Spanish women with an average age of 33.3 years (SD = 13.85; range: 18–74) took part in the study. The majority had university studies (60.7 %), followed by those with only secondary studies (23.5 %).

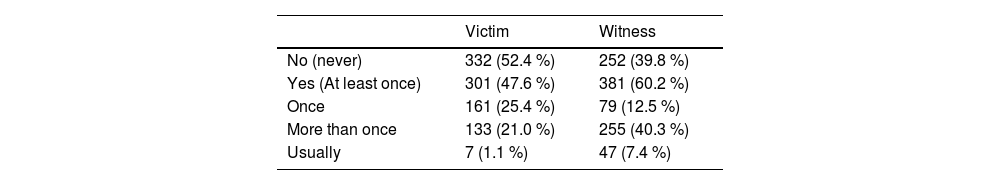

Related to the SH victimization experience, Table 1 show the distribution of the sample.

InstrumentsThe following questionnaires were used:

Brief sociodemographic data questionnaire. Participants were asked for age, gender (self-categorized by participants in an open-ended item) and completed studies.

Brief victimization questionnaire designed ad hoc, including questions with a 4-point scale response about the frequency (Table 1) with which they had been victims or witnesses of SH. Specifically, they were asked directly if they had witnessed SH (bystander) in the workplace and if they had personally experienced any verbal or physical behaviors of a sexual nature (such as comments, jokes, touching, etc.) that had violated their dignity or had created an intimidating, degrading or offensive environment for them (victim). In both cases the response scale ranged from 1 (No, never) to 4 (Yes, usually).

The Questionnaire of Intention to Help in VAW Cases (QIHVC, Ferrer Pérez et al., 2023), designed in a Spanish context, includes vignettes describing hypothetical scenarios of three forms of VAW (including SH at work analyzed in this research). The QIHVC asks about general aspects of the scenarios (such as the perceived severity of violence described in that scenario, on a 7-point scale from Not severe at all to Very Severe; and participant's responsibility to intervene as bystander, on a 7-point scale from Not responsible at all to Completely responsible) and also about the probability of performing different bystander responses in case of being a witness to VAW (results related to these responses are not included in this research). Some participants responded to a scenario where they were the only witness (One bystander condition; n = 345) while others responded to a scenario where they were accompanied by other witnesses (Several bystanders condition; n = 288).

The Illinois Sexual Harassment Myth Acceptance (ISHMA, Lonsway et al., 2008; Spanish adaptation by Expósito et al., 2014) is a 20 items scale with a 7-point Likert-type response format (from 1, Strongly disagree to 7, Strongly agree). High scores reflect greater acceptance of SH myths. The original study and the Spanish adaptation reported a good reliability for the whole scale (α=0.91 in both cases) and for the four dimensions included: fabrication/exaggeration, ulterior motives, natural heterosexuality, and women's responsibility (0.77≥α≤.86). In our sample the internal consistency for the whole scale was lower but appropriate (α=0.83).

Data analysisCategorical variables were coded as dummy variables for making the different analyses (both the victim variable and the witness variable were coded as 0 = No and 1 = Yes; the number of bystanders was coded as 0 = One bystander, and 1 = Several bystanders).

To contrast hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2, two hierarchical regression analyses were carried out (using the variable victim as a predictor in the former, and the variable witness in the latter). These analyses were made controlling the number of bystanders, in order to neutralize the bystander effect described by Darley and Latané (1968) and taking the variable bystander responsibility to intervene as criterion. The order to enter the variables in regression analysis was as follows: in step 1 the covariate (number of bystanders), in step 2 the main predictor (victim in the first analyses, witness in the second), in step 3 the acceptance of SH myths (total score in ISHMA scale), and in step 4 the perceived severity of SH (measured in relation to the SH QIHVC scenario). These analyses were conducted with SPSS 25.

To contrast hypothesis 3, two mediational analyses were carried out using the PROCESS 4.1 macro for SPSS (model 6; Hayes, 2022). The predictor (X) was the variable victim in the first analysis and the variable witness in the second. In both analyses the criteria were the variable bystander responsibility to intervene (Y) and as mediators the variables acceptance of SH myths (M1) and perceived severity of SH (M2). Also in both cases, the variable number of bystanders was included as a covariate. Fig. 1 presents the models contrasted in both cases.

ProcedureThe questionnaires were included on the Lime Survey platform and disseminated through social networks used by the authors and their collaborators. Participants were provided with a link to the webpage where the questionnaires could be found. An introductory text with the objectives and conditions of the study was included, and participants needed to explicitly agree to take part in the study (If they did not agree, participants were unable to answer the questionnaire and their participation was terminated). Lime Survey randomly assigned participants to scenarios with one witness (n = 345 participants) or several witnesses (n = 288 participants).

The research protocol for this study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of xxxx (anonymous only for review purposes) (Ref. 123CER19, 19th November 2019). Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and no incentives were offered to the participants.

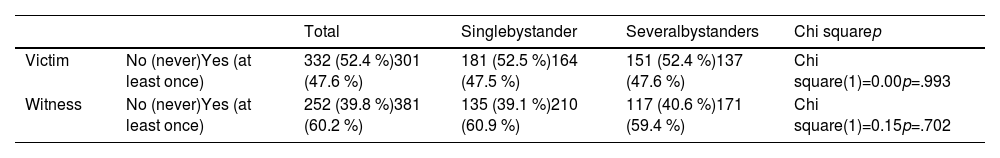

ResultsFirstly, the randomization of scenarios was tested. The results show (Table 2) that there are no differences between the two subsamples (SH victims and witnesses) in terms of the proportion of those who responded to one or another type of scenario (one bystander or several witnesses).

Distribution of participants by SH victimization's experience and number of bystanders.

Next, we present the results of the hierarchical regression analyses made in order to contrast hypothesis 1 and 2 (Table 3).

Predictors of bystander responsibility to intervene in SH.

| Victim | Witness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ∆R2 | B | 95 % CI | ∆R2 | B | 95 % CI | |

| Step 1Number bystanders | .006 | −0.23 | [−0.47, 0.00] | .006 | −0.23 | [−0.47, 0.00] | |

| Step 2Number bystandersMain predictora | .018** | −0.23*0.41** | [−0.47, −0.00][0.17, 0.64] | .006* | −0.230.24* | [−0.47, 0.00][0.00, 0.48] | |

| Step 3Number bystandersMain predictoraMyths acceptance | .021*** | −0.200.35**−0.37*** | [−0.44, 0.03][0.12, 0.58][−0.57, −0.17] | .022*** | −0.200.15−0.38*** | [−0.43, 0.03][−0.09, 0.39][−0.59, −0.18] | |

| Step 4Number bystandersMain predictoraMyths acceptancePerceived severity | .090*** | −0.110.31**−0.24*0.50*** | [−0.33, 0.11][0.09, 0.53][−0.43, −0.04][0.38, 0.62] | .094*** | −0.100.17−0.24*0.51*** | [−0.33, 0.12][−0.06, 0.40][−0.43, −0.05][0.39, 0.63] | |

When we use the variable victim as a predictor (Table 3), and after controlling the variable number of bystanders (Step 1), having been a victim of SH explains a significant part of the variance (1.8 %, p=.001) of the responsibility to intervene (Step 2), in line with hypothesis 1.1. Supporting hypothesis 2, this contribution is maintained, and the explained variance increased by adding to the model the acceptance of SH myths (which in Step 3 adds 2.1 %, p<.001) and the perceived severity of SH (which in Step 4 adds 9.0 %, p<.001).

When we use the variable witness as a predictor (Table 3), and also after controlling the number of bystanders variable (Step 1), having been a witness of SH explains a significant part of the variance (0.6 %) of the responsibility to intervene (Step 2), although at the limit of statistical significance (p=.049). Notably, although this result would be consistent with hypothesis 1.2, this variable stops contributing significantly to the model in the following Steps. In accordance with hypothesis 2, when the variables acceptance of SH myths and perceived severity of SH are added to the model, both enter to it as significant predictors of the responsibility to intervene (the first in Step 3 where explained variance increases by 2.2 %, p<.001, and the second in Step 4 where it adds 9.4 %, p<.001.).

The mediational analyses conducted to contrast hypothesis 3 can be seen in Fig. 2 and Table 4 (for the variable victim as a predictor) and in Fig. 3 and Table 5 (for the variable witness as a predictor).

Mediational analysis. Main predictor having been victim of sexual harassment

All coefficients are non-standardized estimates, B

Total effects are presented in bold font

Solid lines represent significant coefficients; dashed lines represent nonsignificant coefficients

Covariate: Number of bystanders

*p< .05, **p<.01, ***p<.001

Indirect effects on responsibility to intervene via acceptance of SH myths and perceived severity of SH. Main predictor having been victim of SH.

Victim variable is dummy coded (0=No, 1=Yes).

ISHMA: myths acceptance.

PercSev: perceived severity of SH.

ResponsInterv: responsibility to intervene.

95 % confidence intervals were estimated based on 10,000 bootstrap samples.

Significant indirect effects are presented in bold font.

Mediational analysis. Main predictor having been witness of sexual harassment

All coefficients are non-standardized estimates, B

Total effects are presented in bold font

Solid lines represent significant coefficients; dashed lines represent nonsignificant coefficients

Covariate: Number of bystanders

*p<.05 **p<.01 ***p<.001

Indirect effects on responsibility to intervene via acceptance of SH myths and perceived severity of SH. Main predictor having been witness of SH.

Witness variable is dummy coded (0=No, 1=Yes).

ISHMA: myths acceptance.

PercSev: perceived severity of SH.

ResponsInterv: responsibility to intervene.

95 % confidence intervals were estimated based on 10,000 bootstrap samples.

Significant indirect effects are presented in bold font.

Related to the variable victim as a predictor (Fig. 2), we observe a direct effect: having been victim of SH influences the criterion variable in the expected way, conducing to a higher bystander responsibility to intervene (b = 0.31, SE=0.11, p=.006). SH victimization also conduces to a lower acceptance of SH myths (b=−0.15, SE=0.05, p=.001), which in turn leads to a higher bystander responsibility to intervene (b=−0.24, SE=0.10, p=.016) and to a higher perceived severity of SH (b=−0.27, SE=0.06, p<.001); and perceived severity of SH conduces to a higher bystander responsibility to intervene in SH (b = 0.50, SE=0.06, p<.001).

According to hypothesis 3, we have identified two significant indirect effects of having been victim of SH on the bystander responsibility to intervene (Table 4) as expected: first, through acceptance of SH myths (a1b1 effect=0.0361), and second, through the serial mediation of acceptance of SH myths and perceived severity of SH (a1d21b2 effect=0.0206).

Related to the variable witness as a predictor (Fig. 3), there is no significant direct effect of having witnessed SH on the responsibility to intervene in this VAW form (b = 0.17, SE=0.12, p=.138). Have been witness is conducive to a lower acceptance of SH myths (b=−0.23, SE=0.05, p<.001), which in turn leads to a higher bystander responsibility to intervene (b=−0.24, SE=0.10, p=.015) and to a higher perceived severity of SH (b=−0.28, SE=0.06, p<.001). And perceived severity of SH is conducive to a higher bystander responsibility to intervene in SH (b = 0.51, SE=0.06, p<.001).

Although witnessing SH does not directly imply a greater responsibility to intervene, two indirect effects have been observed (Table 5) in the expected direction that would support hypothesis 3: the first through the acceptance of SH myths (a1b1 effect =0.0553), and the second through the serial mediation of the acceptance of SH myths and the perceived severity of SH (a1d21b2 effect =0.0334).

DiscussionOur results support hypotheses 1 and 2 related to the impact of previous victimization experiences as a victim or witness of SH (although the latter only partially), acceptance of SH myths, and perceived severity of SH on the responsibility to intervene. And the mediational analyses conducted also basically support hypothesis 3 in the expected direction. Concretely, having been victim of SH is conducive to a higher bystander responsibility to intervene, either by direct and indirect effects, in the latter case through acceptance of SH myths and perceived severity of SH. And having been witness of SH is conducive to a higher bystander responsibility to intervene, but only by indirect effects through acceptance of SH myths and perceived severity of SH. The significant effect produced by the witness variable when it is introduced as the only predictor, and the fact that this effect disappears when the mediating variables are introduced into the model, would represent a case of what Baron and Kenny (1986) considered “perfect mediation”. This does not occur with the experience of having been a victim, since this variable affects the responsibility to intervene not only by itself, but also indirectly through mediators.

A first promising result provides some answer to a question that, as highlighted by Mainwaring et al. (2023) review, has yielded inconclusive results to date; that is, if previous victimization experiences somehow influence bystander intervention. Although we have not specifically analyzed intervention responses, our results show that witnessing and, in particular, prior SH victimization both increase the sense of responsibility to intervene. As previous research indicates (Arbeit, 2018; Katz et al., 2015; Lyons et al., 2022a; McDonald et al., 2016), it is an important predictor of subsequent intervention. It could be hypothesized that this result is related to the fact that having previously been through a similar situation can increase empathy or identification with the target, therefore increasing that sense of responsibility. In this sense, it is interesting to remember that the ecological model of bystander intervention proposed by Banyard (2011) understands that victimization experiences (such us knowing a victim of sexual assault or being a victim) can enhance the perception of another potential victim and generate emotion and empathy for their situation, thus triggering a sense of responsibility to take action. Further exploration of this issue is necessary, as empathy, or the absence thereof, has been related to other factors, such as blaming or not the victim (Leone et al., 2020; Lyons et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2024).

In fact, previous research has identified that acceptance of rape or SH myths can result in failure to take responsibility for intervening as bystander in these forms of VAW (Lyons et al., 2022a, 2022b; Martini & De Piccoli, 2020; Yule et al., 2020) and has been found as a major barrier to active bystander intervention (Kania & Cale, 2018; Labhardt et al., 2017; Lyons et al., 2021, 2024). Among these myths, attributing the responsibility for controlling the SH to the women victim (blame the victim) has been identified as one of the myths most related to the sense of responsibility to intervene (Lyons et al., 2024; Lonsway et al., 2020). Likewise, our results show that SH myths acceptance leads directly to a lower bystander responsibility to intervene among all participants (women victims and witness of SH). In upcoming research, it may be interesting to further delve into these results by analyzing whether this general effect (produced by the acceptance of myths and evaluated through the total ISHMA score) works similarly across different myth categories (exaggeration, ulterior motives, natural heterosexuality and women's responsibility).

Although these results are promising, this study is not without limitations. Obviously, the most important theoretical limitation of this work is that Burn's model (2009) suggested five barriers to bystander inaction in sexual assault situations, of which this work focuses on only one (failure to take responsibility) and only on some of the identified factors that could hinder interventions at each step of the bystander response process. Related to methodological aspects, a first limitation arises from the convenience/snowball sampling methods used that limit the diversity of participants. In fact, we have studied a young, self-selected, female sample, with a majority of university students, and we did not consider variables such as sexual orientation, gender identity or ethnicity that might be related to bystander barriers (Lyons et al., 2022b). Therefore, the findings should not be generalized beyond the demographic group studied in Spain. Another notable limitation derives from the fact that the sample is made up exclusively of women. Future research should replicate this study with a sample of men to better understand the scope of results. This proposal, however, is not without complications since, as is often noted in the literature on the topic (e.g., Lyons et al., 2022a), gender imbalance is a common feature in psychology studies involving a relatively small number of men.

ConclusionGiven that bystander approach and bystander intervention are an important emerging area of VAW (and also of SH at work) prevention (Campbell & McFadyen, 2017), the results obtained may help to understand how to design prevention programs and the key variables to incorporate. In fact, as Fitzgerald and Cortina (2018) highlight, bystander interventions may prove promising in certain workplace situations and serve at least to redistribute some of the responsibility currently placed on victims to “handle” the problem themselves (p. 229). To improve them we should try to foster bystander awareness and their personal responsibility to intervene, to change their attitudes, and reduce SH myths (Kettrey & Marx, 2021; Mainwaring et al. 2023; Mujal et al., 2021).

FundingThis work has been financed by the State Research Agency (Agencia Estatal de Investigación, AEI) and the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades, MCIU) through the Research Project PID2019–104006RB-I00, funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033

We would like to thank the University of Balearic Islands and the Pontifical University of Salamanca for their support in conducting this research.