Edited by: Óscar F. Gonçalves

More infoMoving towards a systems psychiatry paradigm embraces the inherent complex interactions across all levels from micro to macro and necessitates an integrated approach to treatment. Cortical 5-HT2A receptors are key primary targets for the effects of serotonergic psychedelics. However, the therapeutic mechanisms underlying psychedelic therapy are complex and traverse molecular, cellular, and network levels, under the influence of biofeedback signals from the periphery and the environment. At the interface between the individual and the environment, the gut microbiome, via the gut-brain axis, plays an important role in the unconscious parallel processing systems regulating host neurophysiology. While psychedelic and microbial signalling systems operate over different timescales, the microbiota-gut-brain (MGB) axis, as a convergence hub between multiple biofeedback systems may play a role in the preparatory phase, the acute administration phase, and the integration phase of psychedelic therapy. In keeping with an interconnected systems-based approach, this review will discuss the gut microbiome and mycobiome and pathways of the MGB axis, and then explore the potential interaction between psychedelic therapy and the MGB axis and how this might influence mechanism of action and treatment response. Finally, we will discuss the possible implications for a precision medicine-based psychedelic therapy paradigm.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man (sic) as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern”

Varying degrees of dysfunction across different temporal and spatial scales can result in disorders of mental health. Re-calibration of dysregulated systems across the various levels in order to re-establish homeostasis, depends on a combination of conditions unique to the individual as well as the presence of universal conditions conducive to homeostasis (McDaid et al., 2019; WHO, 2021). An integrated approach across all levels from micro to macro may lead to a more complete understanding of mental health disorders and potentially to improved therapeutic outcomes.

The last two decades have seen major advances in microbiome (Cryan & Dinan, 2012; Cryan et al., 2019) and psychedelic science research (Nichols, 2016; Nutt et al., 2020). Serotonergic psychedelics administered in the context of psychological support can deliver therapeutic benefits for disorders with overly-restricted and/or maladaptive patterns of emotion, behaviour, and cognition (Carhart-Harris & Friston, 2019). Accruing clinical evidence suggests that psychedelic therapy can improve outcomes in depression (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Gukasyan et al., 2022), treatment-resistant depression (TRD) (Carhart-Harris et al., 2018, 2016; Goodwin, et al., 2020) and addiction disorders (Bogenschutz et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2014).

The therapeutic mechanisms underlying psychedelic therapy are complex and traverse molecular, cellular, and network levels. Central activation of the 5-HT2A receptors, particularly in cortical layers are thought to initiate the cascade of altered information processing necessary for therapeutic effects. However, biofeedback signals from peripheral networks and the environment to central networks are key in both the modulation of acute effects and the anticipated trajectory towards sustained therapeutic psychedelic responses. An expanding knowledge of host-microbe interactions may further open the “doors of perception” to reveal patterns of interconnectivity to potentially enhance therapeutic response rates.

It has long been established that the microbial ecosystem is an integral part of host health, particularly in programming immune, metabolic and endocrine systems (de Vos et al., 2022). Preclinical evidence has shown that gut microbes via the gut-brain axis play a role in the regulation of brain development and function (Cryan et al., 2019).

The signalling pathways of the microbiota-gut-brain (MGB) axis operate throughout life, but are especially important during early development, in shaping aspects of the stress response (Sudo et al., 2004), cognition (Desbonnet et al., 2015), and social (Buffington et al., 2016; Desbonnet et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2021) and emotional domains (Cowan et al., 2016).

In humans, perturbations in the gut microbiota are associated with a diverse range of psychiatric disorders. Deciphering the direction of causality is a major challenge (Cryan & Mazmanian, 2022), but there may be general gut microbiota patterns, including depletion of certain anti-inflammatory butyrate-producing bacteria and enrichment of pro-inflammatory bacteria that signify suboptimal homeostasis across psychiatric disorders (Borkent et al., 2022; Kelly et al., 2021; McGuinness et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2018; Nikolova et al., 2021; Valles-Colomer et al., 2019).

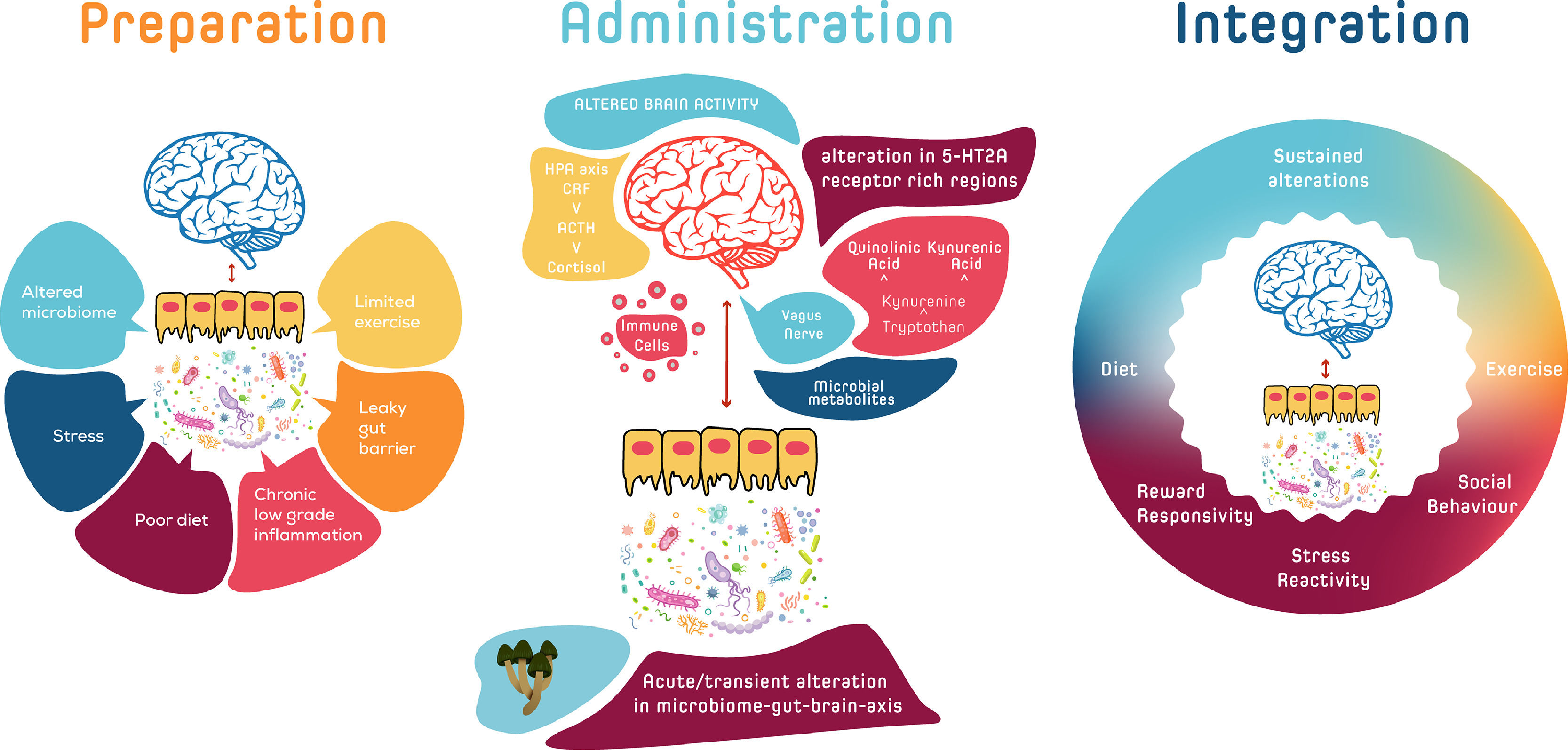

Psychedelic therapy is comprised of three phases; preparation, administration/dosing, and integration. While the MGB axis signalling system operates over different timescales to the centrally acting serotonergic psychedelics, there are several ways by which the integration of the MGB axis, as a convergence hub between multiple biofeedback systems, could play an indirect role in the modulation of acute and sustained symptomatic responses in psychedelic therapy. Baseline MGB axis activity, together with other peripheral mediators and psychological measures, could serve as composite psycho-biomarkers that could be mapped onto the continuum of responses to psychedelic therapy in order to stratify those who may preferentially respond to psychedelic therapy (Kelly et al., 2021). Given the plasticity of MGB axis signalling, which can be rapidly altered following dietary and other approaches (Zhu et al., 2020), it is feasible that the MGB axis, during the preparatory phase or in the pre-preparatory phase, could be shifted into a state which might better respond to psychedelic therapy. In the acute administration phase, the MGB axis may play a subtle role in the inter-individual variability of psychedelic drug metabolism (Clarke et al., 2019). In the integration phase, re-enforcing peripheral mechanisms via synergistic MGB-axis signalling could contribute to the instigation and maintenance of behavioural changes that are more optimal to homeostasis over longer time frames.

A systems-based approach that encompasses the MGB axis and its relationship to the continuum of acute and sustained responses to psychedelic therapy provides an intriguing and potentially clinically useful avenue of further exploration. It has previously been proposed that sustained therapeutic effects of “regular and low doses of psychedelics” particularly those related to sleep, diet and lifestyle factors, could be mediated via the MGB axis (Kuypers, 2019), and that modulation of the gut microbiome by psychedelics (Inserra 2022) may influence immune functions (Thompson & Szabo, 2020). This review of the psilocybiome as a broad concept of reciprocal host-microbiota-psychedelic interactions (Fig. 1) will first discuss the microbiome and pathways of the MGB axis, before moving on to an exploration of the interaction between psychedelic therapy and the MGB axis and how this might influence acute and sustained changes in stress-, social- and reward-processing systems. Finally, we will discuss the implications of the MGB axis for a precision medicine-based psychedelic therapy paradigm.

The possible reciprocal host-microbiota-psychedelic interactions of the Psilocybiome. The MGB axis, as a convergence hub between multiple biofeedback systems, could play a role in the modulation of acute and sustained psychedelic responses in psychedelic therapy. In the preparatory phase, baseline MGB axis activity, together with other peripheral mediators and psychological measures, could serve as composite psycho-biomarkers that could be mapped onto the continuum of responses to psychedelic therapy in order to stratify those who may preferentially respond to psychedelic therapy. During the pre-preparatory or preparatory phase the MGB axis could be shifted into a state which might better respond to psychedelic therapy. In the acute administration phase, the MGB axis may play a subtle role in the inter-individual variability of psychedelic drug metabolism. In the longer-term, re-enforcing peripheral mechanisms via synergistic MGB-axis signalling could contribute to the instigation and maintenance of behavioural changes that are more optimal to homeostasis.

Microbes have inhabited the planet for approximately 3.5–3.7 billion of the earth's 4.5 billion years (Grosberg & Strathmann, 2007; Nutman et al., 2016). The first animals emerged 800 million years ago, with homo sapiens relative latecomers at 350,000 years old (Hublin et al., 2017). Every stage of the co-evolutionary timeline of increasing complexity occurred in a microbial world, which has led to an interconnected physiology between microbes and hosts. There are as many microbial cells in the human body as human cells, numbering 40 trillion (Sender & Fuchs, 2016). This complex composite of microbial and human cells and genes, known as the “holobiont”, expands the organismic boundaries and confines of the self to encompass bidirectional information exchange processes with our microbial ecosystem (Cryan et al., 2019; Theis et al., 2016).

This co-evolutionary lineage of increasing layers of interconnected material complexity and communication pathways between micro and macro levels – each influencing each other, to eventually culminate in processing systems that are able to reflect on the entire (known) evolutionary journey and alter its direction – is all the more important in this era of ecosystem disequilibrium (Almond & Petersen, 2020; Ceballos et al., 2017; Cobb, 2020; Johnson et al., 2020; Lent, 2017; Sheldrake, 2020; Watts et al., 2021). Analogous to the proposed synergistic relationship between contact with the natural environment and psychedelics (Gandy et al., 2020; Kettner et al., 2019; Lyons & Carhart-Harris, 2018), exploration of the molecular constellations and associated information pathways of interconnectivity between the microbial ecosystem and psychedelic therapy is at the forefront of systems neuroscience.

Fungi and psilocybinAt 1 billion years old, fungi are evolutionary younger microorganisms than bacteria (Bonneville et al., 2020; Loron et al., 2019). They form enmeshed relationships with bacteria (Deveau et al., 2018) and plants (Kiers et al., 2011) and are especially important for decomposition and regeneration, including the degradation of various environmental pollutants (Akhtar & Mannan, 2020; Dusengemungu et al., 2021; Sheldrake, 2020). There are 120,000 known species of fungi, but escalating estimates based on high-throughput sequencing techniques suggest as many as 12 million, revised from previous estimates of 5.1 million (Hawksworth, 2001; Wu et al., 2019). Mushrooms containing psilocybin, numbering approximately 200, mostly from the genus Psilocybe, are estimated to be 10–20 million years old and may have evolved separately more than once (Kosentka et al., 2013). It is not known why some mushrooms produce psilocybin. An intriguing, though tenuous, evolutionary theory based on a comparative genomic analysis of hallucinogenic fungi with non-hallucinogenic relatives posited that psilocybin may have provided a fitness advantage in certain environments by altering the behaviour of predatory insects, to decrease the chances of the fungi getting eaten (Awan et al., 2018; Reynolds et al., 2018).

Other fungi also alter host behaviour. Massospora is a fungus that infects insects. When it infects cicadas, it produces psilocybin and the amphetamine cathinone, which are associated with the alteration of some of its hosts behavioural patterns (Boyce et al., 2019; Cooley et al., 2018). Similarly, the fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis manipulates behaviour in certain species of ants (de Bekker et al., 2014; Mangold et al., 2019). Even more remarkable is that the fungal behavioural control in some ant species may occur in the periphery, via extensive networks in muscles (Fredericksen et al., 2017).

Psychoactive fungi can also alter human behaviour. Accidental consumption of the alkaloid ergotamine – a precursor to lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which is produced by the fungus Claviceps purpurea that grows on grains/rye – can alter human behaviour and perception (Correia et al., 2003; Eadie, 2003). More subtle unintentional ingestion of toxic fungal secondary metabolites or mycotoxins in food contaminants occurs today (Eskola et al., 2020; Lindell et al., 2022). While the contribution of psychedelic mushrooms to the evolutionary shaping of human faculties is speculative (Rodríguez Arce & Winkelman, 2021), intentional consumption in ritual/ceremonial settings by humans is thought to have occurred for several millennia (Miller et al., 2019; Robinson et al., 2020; Rodríguez Arce & Winkelman, 2021).

Gut microbiome and mycobiomeMost of the human body's microbes reside in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). The vast majority are bacteria (Zhernakova et al., 2016). Viruses and bacteriophages, protozoa, archaea, and indeed fungi are also present but in much smaller proportions (Lankelma et al., 2015). Fungal populations or the mycobiome within the microbiota comprise 0.001–0.1% of the total gut microbiome and are dominated by yeasts (Hallen-Adams & Suhr, 2017; Nash et al., 2017). The mycobiome is less stable than the microbiome, with less, if any colonization continuity (Auchtung et al., 2018; Hallen-Adams & Suhr, 2017; Lavrinienko et al., 2021; Suhr & Hallen-Adams, 2015). Similar to the gut microbiome, the gut mycobiome is shaped by geography, urbanization, ethnicity, and diet (Sun et al., 2021). Both the microbiome and the less studied mycobiome interact in complex ways to collectively shape host homeostasis, especially that of immune (Leonardi et al., 2018; van Tilburg Bernardes et al., 2020) and metabolic systems (Mims et al., 2021; Sanna et al., 2019).

Defining the optimal gut microbiome is challenging given the extensive individual differences between the microbiomes of healthy people (Falony et al., 2016; Gacesa et al., 2022; The Human Microbiome Project et al., 2012). However, it is generally thought that diverse gut microbiome composition and stability are beneficial for human health (Bäckhed et al., 2012; Lozupone et al., 2012). There are some indicators that certain gut microbial species have been lost and alpha-diversity (distribution of species abundances within a sample) reduced as humans entered the industrialized age, but the precise implications for human health are not fully known (De Filippo et al., 2010; Moeller et al., 2014; Olm et al., 2022; Smits et al., 2017).

Communication channels: microbiota-gut-brain (MGB) axisOver the last two decades, notwithstanding the aforementioned challenges in translation, there have been advances in the mechanistic understanding of how the gut microbiota communicate with the brain (Forssten et al., 2022; Nagpal & Cryan, 2021). Germ-free (GF) rodents (born and raised without microbes), antibiotics, probiotics, gastrointestinal (GI) infection studies, and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) rodent studies have progressed the understanding of the mechanisms by which the gut microbiota can influence brain development and function via the gut-brain axis. This MGB signalling system communicates with the brain via stimulation of immune pathways (Erny et al., 2015), vagus nerve activation (Fülling et al., 2019), production of circulating microbial metabolites and/or microbial induction of host molecules (short-chain fatty acids (SCFA's), (O'Riordan et al., 2022), amino acid derivatives (catecholamines, and other indole derivatives), and secondary bile acids, as well as stimulation of enteroendocrine cells and enteric nervous system signalling (Ye et al., 2021), tryptophan metabolism (O'Mahony et al., 2015) and the HPA axis (Sudo et al., 2004). Some of these pathways may serve as overlapping, indirect points of convergence in the trajectory of psychedelic therapy.

Tryptamines and the MGB axisPsilocybin and psilocin are tryptamines or tryptophan indole-based monoamine alkaloids (indolalkylamines) (Lenz et al., 2021). Tryptamines are derived from the decarboxylation of tryptophan, which is an essential amino acid acquired from the diet, and the precursor for serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) and melatonin (Fricke et al., 2017; Sherwood et al., 2020). After ingestion, psilocybin is rapidly dephosphorylated by alkaline phosphatases in the intestine and liver to the biologically active psilocin, which is then absorbed from the stomach and small intestine into circulation and can cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) (Dinis-Oliveira, 2017). Psilocin can be further metabolized by a demethylation and oxidative deamination catalysed by liver Monoamine oxidases (MAO) or aldehyde dehydrogenase (Dinis-Oliveira, 2017). Further metabolism of psilocin by glucuronidation of the hydroxyl group to psilocin O-glucuronide occurs by UDP glucuronosyltransferases (UGT)1A10 in the small intestine and likely UGT1A9 in the circulation (Dinis-Oliveira, 2017; Manevski et al., 2010). (For a detailed review of the metabolism of psilocybin and psilocin see Dinis-Oliveira 2017). Certain psychotropics are subject to glucuronidation, a process which may be influenced by the gut microbiota (Clarke, et al., 2019; Cussotto et al., 2021). But it is not yet known whether microbes play a role in the glucuronidation of psilocin.

The structural similarity of psilocybin and psilocin to other indoles suggests the possibility that these are interkingdom signalling molecules (Lee et al., 2015). The largest reserve of 5-HT is located in enterochromaffin cells in the GIT (Mawe & Hoffman, 2013). 5-HT is an important signalling molecule in the gut-brain-axis under the direct or indirect influence of the gut microbiota (Clarke et al., 2013; O'Mahony et al., 2015; Yano et al., 2015). Gut bacteria-produced tryptamine can activate the epithelial G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) 5-HT4 to increase GI transit (Agus et al., 2018; Bhattarai et al., 2018). Tryptamine can induce the release of 5-HT by enterochromaffin cells, and enteric neurons are able to take up tryptamine, which displaces 5-HT in intracellular synaptic vesicles, resulting in 5-HT release (Gheorghe et al., 2019; Israelyan et al., 2019). Furthermore, gut microbes, such as Clostridium sporogenes and Ruminococcus gnavus can decarboxylate tryptophan to tryptamine which can activate host receptors (Bhattarai et al., 2018; Cryan et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2014). Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum 35,624 has been shown to increase plasma tryptophan levels in rats (Desbonnet et al., 2008) and increase Tryptophan Hydroxylase expression and secretion of 5-hydroxytryptophan in vitro (Tian et al., 2019). Certain gut microbes can also produce tyramine, a trace amine derived from the amino acid tyrosine, that acts as a neurotransmitter and catecholamine-releasing agent and which can activate dopaminergic GPCRs (Colosimo et al., 2019).

Monoamine oxidases (MAO) A and B are the primary enzymes involved in tryptamine metabolism to produce indole-3-acetaldehyde (MetaCyc, 2022). A recent study indicated that some Psilocybe species (P. cubensis, P. Mexicana, P. semilanceata, P. cyanescens) produce harmane, harmine, and other l-tryptophan-derived β-carbolines (Blei et al., 2020), which act as reversible MAO-A inhibitors. There are indications that host-microbiota-metabolome interactions may have implications for inter-individual variability in the metabolism of tryptamines. For example, a study in mice showed that Morganella morganii, a gram-negative gut commensal, converted the essential amino acid L-Pheinto phenethylamine into the potent psychoactive trace amine phenethylamine (Chen et al., 2019). When combined with the non-selective and irreversible MAO inhibitor (MAO-I) phenelzine, M. morganii triggered phenethylamine toxicity (Chen et al., 2019). Taken together, it is conceivable that certain gut microbiota configurations and associated signalling pathways may play a subtle role in the inter-individual variability of psychedelic metabolism. However, the landscape for host-microbiota-psychedelic interactions in drug metabolism has yet to be fully explored.

Kynurenine pathwayThe kynurenine pathway (KP) is an alternative metabolic route for tryptophan. A large majority of tryptophan is metabolized along the KP giving rise to molecules collectively referred to as “kynurenines” (Gheorghe et al., 2019). Enzymes of the KP are immune- and stress-responsive (O'Mahony et al., 2015) and are partially regulated by the gut microbiota (O'Mahony et al., 2015). As discussed above, the availability of tryptophan is also altered by gut microbes generating either indole and its derivatives, tryptamine or 5-HT, which can affect GI function (Gheorghe et al., 2019). Dysregulated tryptophan metabolism can occur under conditions of stress or inflammation in both the gut and the brain to alter gut-brain axis signalling. During stress or immune activation, tryptophan can be preferentially converted to kynurenine rather than 5-HT in the gut, with implications for GI motility and function. Tryptophan is metabolized along the KP by microglia and astrocytes in the brain leading to the formation of either kynurenic acid (KYNA) or quinolinic acid (QUIN) (Gheorghe et al., 2019). The KYNA and QUIN balance has implications for psychiatric disorders (Gheorghe et al., 2019; Savitz, 2020). For a detailed review on microbial regulation of tryptophan and KP metabolism, see (Gheorghe et al., 2019).

Previous studies suggest that KP metabolites may play a role in SSRI (Bhattacharyya et al., 2019; Erabi et al., 2020) and ketamine treatment response (Verdonk et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2018). In a single-arm, open-label study of 84 medicated patients with unipolar and bipolar depression, intravenous (IV) ketamine increased serum KYNA levels and the KYNA/kynurenine ratio at 24 h following the first infusion in responders compared to non-responders, and this elevation lasted up to 14 days, associated with improvements in depressive symptoms (Zhou et al., 2018). In mice, a single dose of intraperitoneal (IP) ketamine restored lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced depressive-like alterations and decreased cytokine production, microglial activation in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and QUIN production (Verdonk et al., 2019). In the human part of the same study, which included 15 medicated inpatients with TRD (and 15 age and sex matched healthy controls), plasma KYNA/QUIN predicted (IV) ketamine response, and a reduction in QUIN was associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms (Verdonk et al., 2019). These studies did not explore the gut microbiota, but preclinical studies indicate that ketamine can alter the gut microbiota (Table 1). It is not yet known whether the serotonergic psychedelics influence host-microbe control over tryptophan and KP metabolism, and whether this would have any clinically relevant impact on response rates in psychedelic therapy.

Gut microbiota and psychotropics.

| Ketamine | ||

|---|---|---|

| Design | Currently proposed primary mechanism of action | Effect on the gut microbiome |

| male rats, ketamine 2.5 mg/kg 7 days, IP | N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonist | increase in Lactobacillus, Turicibacter and Sarcina and decrease in opportunistic pathogens Mucispirillum and Ruminococcus vs saline. alpha diversity: no significant difference (Getachew et al., 2018) |

| in vitro (ketamine and propofol mix) | antimicrobial activity against E.coli, P.aeruginosa and C.albicans. S.aureus not inhibited (Begec et al., 2013) | |

| in vitro | dose dependent antimicrobial activity against: S.aureus, S.pyogenes, S.epidermidis, E.faecalis, P.aeruginosa and E.coliS.aureus and S.pyogenes most sensitive (Gocmen et al., 2008) | |

| in vitro | antimicrobial activity against Stachybotrys chartarum, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Borrelia burgdorferi (Torres et al., 2018) | |

| MDMA | ||

| male rats, MDMA 20 mg/kg, single dose, subcutaneous | inhibits serotonin (SERT), norepinephrine (NET), and dopamine transporters (DAT) | increase in cecal Proteus mirabilis vs placebo, antibiotics reduced MDMA-induced hyperthermia (Ridge et al., 2019) |

| SSRI's | ||

| male mice, escitalopram 10 mg/kg, oral gavage, daily stress (CUMS) | inhibits SERT | responder group: increase in Prevotellaceae UCG-003, and decrease in Ruminococcaceae and Lactobacillaceae vs non-responder group. escitalopram increased alpha-diversity (Duan et al., 2021) |

| male mice, amitriptyline (25 mg/kg/d) or fluoxetine (12 mg/kg/d) for 6 weeks, oral gavage, daily stress (CUMS) | increase in Bacteroidetes and decrease in Firmicutes, increase in Porphyromonadaceaeincrease in Bacteroidaceae associated with Ami, not Fluincrease in Parabacteroides, Butyricimonas, and Alistipes in Ami and Flualpha diversity increased in Ami and Flu (Zhang et al., 2021) | |

| male rats, 28 days fluoxetine 10 mg/kg/day, escitalopram 5 mg/kg/day, in drinking water | fluoxetine inhibited growth of cecal Succinivibrio and PrevotellaSSRIs: increase ileal but not colonic permeabilityin vitro: escitalopram antimicrobial activity against E.coli, but not L.rhamnosus.Fluoxetine antimicrobial activity against L.rhamnosus and E.coliIn vitro: escitalopram had antimicrobial effect on E. coli, but no effect on L. rhamnosusFluoxetine: strong dose-dependent antimicrobial activity against L. rhamnosus and E. coli (Cussotto et al., 2019) | |

| male mice, 29 days fluoxetine 20 mg/kg/day, oral gavage | decrease in L.johnsonii and Bacteroidales S24–7alpha diversity: no significant difference (Lyte et al., 2019) | |

| male mice, 21 days fluoxetine and escitalopram 10 mg/kg/day, IP injections | decrease in Ruminococcus (Lukić et al., 2019), alpha diversity: decrease | |

| male rats, 21 days of 2 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, daily stress (Fluoxetine) | decrease in Prevotellaceae Ga6A1 and increase in Ruminoclostridium 6 and Ruminococcaceae NK4A214alpha diversity: no significant difference (Zhu et al., 2019) | |

| male and female mice, 7 days fluoxetine 10 mg/kg/day, oral gavage | decrease in Turicibacter (Fung et al., 2019) | |

| male mice, 21 days fluoxetine 12 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, daily stress (CUMS) | Fluoxetine altered Erysipelotrichia; Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria, and Epsilonproteobacteria (Sun et al., 2019) | |

| female rat model of maternal vulnerability, heterozygous SERT knockout (SERT+/−), 10 mg/kg fluoxetine, oral gavage | increase in Prevotella and Ruminococcus during pregnancy and lactation in fluoxetine, and decreased fecal amino acids.amino acid concentrations correlated negatively with Prevotella and Bacteroides (Ramsteijn et al., 2020) | |

| Sertraline, in vitro | Potent antimicrobial against E. coli (Bohnert et al., 2011)Inhibits the growth of S. aureus, E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Ayaz et al., 2015)Potent antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioides immitis and Candida spp. (Lass-Flörl et al., 2003; Paul et al., 2016; Rossato et al., 2016; Treviño-Rangel Rde et al., 2016; Zhai et al., 2012)Inhibits Leishmania donovani (Palit & Ali, 2008) | |

| Phencyclidine | ||

| male rats, 7 days phencyclidine 5 mg/kg IP | N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonist | impaired novel object recognition, ampicillin abolished the subPCP-induced memory deficitincrease in Lachnospiraceae and Clostridiaceae, including the Roseburia and Odoribacter genus in subPCP (Pyndt Jorgensen et al., 2015) |

| DOI | ||

| male mice, offspring of maternal immune activation mouse model (influenza virus), DOI 0.5 mg/kg IP | 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C agonist | adult offspring exhibited altered gut microbiota profiles, up-regulated frontal cortex 5-HT2A receptors,increased DOI induced head twitch behaviour and cognitive deficits in the novel object recognition test5-HT2A receptor density positively correlated with Ruminococcaceae and Candidatus (saccharibacteria), trend negative correlation with Lactobacillaceaestreptomycin in the prepubertal stage prevented cognitive impairment, but not 5-HT2AR changes (Saunders et al., 2020) |

MDMA; 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, DOI; 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl-2-aminopropane, IP; intraperitoneally, SSRI; Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, CUMS; chronic unpredictable mild stress, Ami; amitriptyline, Flu; Fluoxetine, PCP; phencyclidine.

The gut microbiota plays a key role in regulating immune system homeostasis by maintaining pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signalling in the GIT (Ansaldo et al., 2021; Schirmer et al., 2016). The immune system is regulated by a plethora of ligands and signalling molecules produced by microorganisms in the gut, such as SCFA's, including butyrate, propionate, and acetate. Other examples include polyamines, linoleic acid metabolites, tryptophan metabolites, trimethylamine-N-oxide, vitamins, and secondary bile acids (Hertli & Zimmermann, 2022). Lack of balanced gut microbiota plays a role in various autoimmune diseases and given the role of T cells in classical neuroinflammatory diseases, there is a growing awareness of the likely relevance of the gut-brain axis in immune dysregulation that affects CNS function via microglial activation, pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, molecular mimicry, anti-neuronal antibodies, self-reactive T cells and disturbance of intestinal and BBB in psychiatric disorders (Ivanov et al., 2022; Medina-Rodriguez et al., 2020; Pape et al., 2019; Pearson-Leary et al., 2020).

Serotonergic psychedelics have immuno-modulatory properties (Szabo, 2015; Szabo et al., 2014, 2016; Thompson & Szabo, 2020). In vitro studies have demonstrated that psilocin and dimethyltryptamine (DMT) reduced levels of TLR4, p65 and CD80 proteins, and upregulated TREM2 in mouse primary microglia cells (Kozłowska et al., 2021), whereas extracts from psilocybin-containing mushrooms inhibited LPS-induced production of TNF-α and IL-1β in human U937 macrophage cells (Nkadimeng et al., 2021). (For a review of immune related proteins see Beumer et al. 2012). In the small intestine, the selective 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (R)-DOI inhibited a variety of TNF-α induced mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory markers mediated via the 5-HT2A receptor (Nau et al., 2013).

Similar anti-inflammatory effects, via 5-HT2A receptor activation, were observed in rodent aortic smooth muscle (Yu et al., 2008) and in models of asthma (Flanagan et al., 2019) and cardiovascular disease (Flanagan et al., 2019). The gut microbiota may further moderate the immuno-modulatory properties of serotonergic psychedelics. A maternal immune activation mouse model demonstrated a link between the gut microbiota and responses to DOI (Saunders et al., 2020). Adult male offspring exhibited altered gut microbiota profiles, up-regulated 5-HT2A receptors in the frontal cortex, increased DOI induced head-twitch behaviour (rapid side-to-side rotational head movement that occurs in rodents after administration of 5-HT2A agonists), and cognitive deficits in the novel object recognition test (Saunders et al., 2020). 5-HT2A receptor density correlated with gut Ruminococcaceae (Saunders et al., 2020). Oral antibiotics in the prepubertal stage prevented the cognitive impairment, but not the change in 5-HT2A receptor density or head-twitch behaviour in response to challenge with DOI (Saunders et al., 2020).

Interestingly, the prebiotic (galacto-oligosaccharides) prevented an LPS-mediated increase in 5-HT2A receptor density in the frontal cortex in mice (Savignac et al., 2016), whereas the antibiotic ampicillin abolished an impairment in novel object recognition induced by sub-chronic doses of the non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist phencyclidine in rats (Pyndt Jorgensen et al., 2015) (Table 1). In humans, an exploratory study of the short-acting psychedelic 5-MeO-DMT in healthy volunteers (n = 11) found a significant decrease in salivary IL-6, but no changes in CRP and IL-1β, and increases in salivary cortisol levels (Uthaug et al., 2020) (Table 2). Ayahuasca reduced CRP levels in both TRD patients, and a comparison group of healthy adults compared to placebo, though there were no significant changes in IL-6 levels (Galvão-Coelho et al., 2020; Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019). Further exploration of the immuno-modulatory effects of serotonergic psychedelics and how they may be influenced by the gut microbiota could advance mechanistic insights.

Serotonergic psychedelics and acute changes in peripheral markers in humans.

| Psychedelic | Group | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Ayahuasca(single dose) | TRD (n = 29), HC (n = 45)antidepressant freeparallel arm, randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled | decrease in blood CRP in TRD and HCs vs placebo, no significant changes in IL-6correlation between larger reductions of CRP and lower depressive symptoms 48 h after aya in TRDincrease in salivary cortisol levels in both TRD and HCs, 48hours after aya: no differences in CAR or plasma cortisol between the groups (Palhano-Fontes et al., 2019; Galvão et al., 2018; Galvão-Coelho et al., 2020)increase in BDNF at day 2 vs placebo in TRD and HC, but no significant differences between TRD and HC (de Almeida et al., 2019) |

| Ayahuasca(single dose) | HC (n = 22)randomized, placebo-controlled | no change in blood BDNF (Rocha et al., 2021) |

| Ayahuasca(single dose) | Social anxiety disorder (n = 17)Randomized, placebo-controlled | no change in blood BDNF (Dos Santos et al., 2021) |

| Psilocybin (45, 115, 215, 315 µg/kg) | HC (n = 8)double-blind placebo-controlled | acute increase in plasma ACTH, cortisol, prolactin and TSH (Hasler, et al., 2004) |

| 5-MeO-DMT (inhaled) | HC (n = 11)non-controlled | significant increase in salivary cortisol and decrease in IL-6 (30 min before & after 90 min after 5-MeO-DMT)no changes in CRP and IL-1β (Uthaug, et al., 2020) |

| N,N DMT (IV) | HC (n = 12)experienced psychedelic usersrandomized placebo-controlled | acute dose dependent increase in blood cortisol, corticotropin, prolactin, growth hormone and ß-endorphinall endocrine markers returned to baseline 5 h post N,N DMTno change in serum melatonin (Strassman & Qualls, 1994; Strassman et al., 1996) |

| LSD(200 μg) | HC (n = 16)randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over | increase in plasma cortisol, cortisone, corticosterone, 11-dehydrocorticosterone, and androgen dehydroepiandrosterone vs placebono changes in other androgens, progestogens or mineralocorticoids vs placebo (Strajhar et al., 2016) |

| LSD(200 μg) | HC (n = 16)double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover | increase in plasma cortisol, prolactin, oxytocin, and epinephrine (Schmid, et al., 2015) |

| LSD(25, 50, 100, 200 µg) | HC (n = 16)double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover | increase in blood BDNF at 200 µg vs placebo (Holze, et al., 2021) |

| LSD(5, 10, 20 μg) | HC (n = 23, n = 5 all-time points)within-subject placebo-controlled | increase in blood BDNF at 4 h (5 μg) and 6 h (5, 20 μg) vs placebo (Hutten et al., 2021) |

| LSD(100 µg) | HC (n = 17)randomized, placebo-controlled crossover | increase in sympathetic activity (electrocardiographic recordings) (Schmid, et al., 2015) |

TRD, HC, CRP; reduced C-reactive protein, IL; interleukin, TSH; thyroid stimulating hormone, h; hours, CAR; cortisol awakening response, BDNF; brain-derived neurotrophic factor, ACTH; adrenocorticotropic hormone, 5-MeO-DMT; 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine, N,N-dimethyltryptamine, min; minutes, IV; intravenous, vs; versus.

It has long been established that chronic exposure to stress, which exceeds the individual's coping capacity (allostatic load) can lead to adverse mental health outcomes (McEwen, 2017). The MGB axis is one of the systems that plays a role in stress regulation. Stress alters the gut microbiota, and alteration of the microbiota mediates stress responsivity (Foster et al., 2017), particularly the HPA axis (Sudo et al., 2004), the main neuroendocrine regulator of stress responses. Early life stressors are especially potent sensitizers of the stress response system, including the MGB axis (Clarke et al., 2013).

Administration of serotonergic psychedelics acutely stimulates the HPA axis in animals and humans via central and peripheral actions (Galvão-Coelho et al., 2020; Hasler et al., 2004; Schindler et al., 2018; Uthaug et al., 2020). 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C and 5-HT1A receptors are expressed in the hypothalamus, and serotonergic psychedelics can stimulate corticotropin releasing hormone release and dose dependent increases in serum adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosterone/cortisol (Schindler et al., 2018). (For a review of the neuroendocrine effects of serotonergic psychedelics see (Schindler et al., 2018). A study in male mice suggested that the acute anxiogenic effects induced by psilocybin were associated with the post-acute anxiolytic effects (Jones et al., 2020). This study showed that chronic corticosterone administration suppressed the psilocybin induced acute corticosterone and behavioural changes (Jones et al., 2020). The authors postulated that psilocybin may act as an initial stressor that provides resilience to subsequent stress (Jones et al., 2020).

Stress-induced alterations in amygdala 5-HT2A receptor-signalling may be one point of convergence between the serotonergic psychedelics and the MGB axis. Preclinical data suggests that the gut microbiota influences amygdala structure and function (Hoban et al., 2017; Luczynski et al., 2016; Pinto-Sanchez et al., 2017; Stilling et al., 2018). Psychedelics acutely alter amygdala reactivity, with sustained effects of at least one month in some people (Barrett et al., 2020). This may be associated with a shift in emotional reactivity from a negative to a positive bias (Grimm et al., 2018; Kometer et al., 2012; Kraehenmann et al., 2015). Given the aforementioned perturbations of the gut microbiota in stress-related psychiatric disorders (Borkent et al., 2022; McGuinness et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2018; Nikolova et al., 2021; Valles-Colomer et al., 2019), exploration of the interaction of the MGB axis and peripheral and central components of the stress response system could potentially increase overlapping resilience strategies to decreased rates of relapse in stress-related psychiatric disorders after psychedelic therapy.

MGB axis and social processingSocial processes involve a complex interplay of social reward circuits, molecular signalling pathways, and environmental cues. Social network interconnectivity includes socially distributed symbiotic microbes, required for the development and maintenance of social processes (Buffington et al., 2016; Desbonnet et al., 2014; Sherwin et al., 2019; Stilling et al., 2018). In a human study (n = 655), people with larger social networks had more diverse gut microbiota composition (Johnson, 2020). Conversely, anxiety and stress were associated with reduced gut microbiota profiles (Johnson, 2020). A number of pathways of the MGB axis can influence social behaviour. The HPA axis is intertwined with the expression of social behaviours. A recent study in male mice showed that reducing HPA axis-mediated production of corticosterone via the gut microbiota altered social behaviour (Wu et al., 2021). The same study suggested that Enterococcus faecalis restored social deficits and reduced corticosterone levels following social stress (Wu et al., 2021).

Psychedelic therapy, heavily dependent on context, can alter social processing and potentially foster increased levels of perceived connectivity (Kettner et al., 2021; Watts et al., 2017). Higher levels of perceived connectivity, whether social or otherwise, can strengthen resilience against stressors. Social isolation (and perceived sense of disconnection) can precipitate stress. An 8-week social isolation model in juvenile marmosets, resulted in decreased fecal cortisol levels in both ayahuasca and saline treated groups, though in the male animals, ayahuasca reduced scratching (a stress related stereotypic behaviour) and increased feeding behaviour (da Silva et al., 2019).

In addition to the HPA stress response, other overlapping signalling pathways, such as oxytocin, which are under the partial influence of the gut microbiota, influence social processes (Erdman, 2021; Sgritta et al., 2019). Serotonergic psychedelics can increase oxytocin (Schmid et al., 2015), but similar to acute activation of the HPA axis, the implications for psychedelic therapy have yet to be established. Although not a classical psychedelic, 3,4-ethylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) can modulate oxytocin-mediated synaptic plasticity in the nucleus accumbens in mice, which is necessary for social reward learning (Nardou et al., 2019). The gut microbiota was not measured in this study, but another preclinical study showed that MDMA increased Proteus mirabilis in the caecum, while treatment with antibiotics reduced MDMA-induced hyperthermia, suggesting a role of the MGB axis in thermoregulation (Ridge et al., 2019). These studies prompt further investigation into the MGB axis and its interaction with neuroendocrine responses in contributing to the potential alterations in social processing over the trajectory of psychedelic therapy.

MGB axis and rewardPreliminary clinical studies show that psychedelic therapy may have a therapeutic role in overcoming alcohol use disorder (Bogenschutz et al., 2022; Krebs & Johansen, 2012) and nicotine addiction (Garcia-Romeu et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2014; Noorani et al., 2018). Several trials are underway to explore psychedelic therapy for other addiction disorders (e.g. cocaine, methamphetamine, opioids). There has been increasing interest in the role of the MGB axis in the various aspects of reward processing (García-Cabrerizo et al., 2021; Han et al., 2018). Microbiome depletion antibiotic rodent models indicate that the microbiome may play a role in sensitising rodents to cocaine reward (Kiraly et al., 2016), and variability in gut microbiota profiles may be associated with altered cocaine consumption in rats (Suess et al., 2021). Similarly, microbiome depletion rodent models suggest the gut microbiome alters brain circuitry in opioid (oxycodone) intoxication and withdrawal (Simpson et al., 2020).

Alcohol also alters the gut microbiota (Peterson et al., 2017), which may contribute to alcohol addiction cycles via bidirectional communication pathways involving immuno-kynurenine (Leclercq et al., 2021), intestinal permeability (Leclercq et al., 2014), metabolic pathways (Leclercq et al., 2020), and alterations in dopaminergic signalling (Carbia et al., 2021; González-Arancibia et al., 2019; Jadhav et al., 2018). Recently, a translational study using antibiotic and FMT rodent models showed that metabolic disturbance and weight gain associated with smoking cessation were partially dependent on the gut microbiome (Fluhr et al., 2021).

While the central activity of psychedelic compounds are primary, these studies propose that the MGB axis might play an overlapping role, albeit over different time scales, with psychedelic therapy in gating reward valence and therefore in the modulation of complex reward-related behavioural patterns or habits (Dong et al., 2022; García-Cabrerizo et al., 2021; Meckel & Kiraly, 2019; Salavrakos et al., 2021). This synergistic combination of MGB axis and psychedelic therapy could help to restructure reward-processing pathways to overcome various addiction cycles, particularly in maintaining abstinence in the post-psychedelic therapy phase.

The gut microbiota, dietary and physical activity patternsThere is increasing recognition that diet, via multiple overlapping biological pathways may be a modifiable risk factor for mental health disorders. Notwithstanding subtle personalised gut microbiota signatures and associated metabolic function (Liu et al., 2020), there are broad dietary inputs that are optimal for system homeostasis, such as plant-based diets with a high content of grains/fibres, fermented foods and fish (Deehan et al., 2020; Dinan et al., 2019; Reynolds et al., 2019). Conversely, it is established that processed or fried foods, refined grains and sugary products are broadly detrimental to mental health (Khambadkone et al., 2020; Oddy et al., 2018).

Diet is the primary contributing factor to the gut microbiome and can rapidly alter its composition (David et al., 2014). Certain dietary patterns are associated with gut microbial signatures (De Filippis et al., 2016). Lower gut microbiota diversity is associated with low-fiber western diets (Sonnenburg & Sonnenburg, 2019; Vangay et al., 2018), whereas high-fermented-food diets may increase microbiota diversity and decrease inflammatory markers (Wastyk et al., 2021) and alter tryptophan metabolites (Zhu et al., 2020). A high-fat diet rodent model of depression showed that plasma tryptophan indole-metabolites and bile acids inversely correlated with gut microbiota signatures (Abildgaard et al., 2021).

Dietary or feeding patterns are governed by a balance between homeostatic and reward seeking systems (Murray et al., 2014; Rossi & Stuber, 2018). The meso-corticolimbic circuit and serotonergic and dopaminergic signalling are essential for homeostatic and reward-associated regulation of feeding behaviour and systemic energy metabolism. Preclinical studies indicate that MGB axis signalling contributes not only to homeostatic and energy metabolism regulation, but also the regulation of feeding behaviour (Alcock et al., 2014; Gabanyi et al., 2022; García-Cabrerizo et al., 2021; Leitão-Gonçalves et al., 2017; Trevelline & Kohl, 2022).

A re-appraisal of maladaptive or aberrant or unhealthy eating habits/dietary patterns, across the spectrum from overly restrictive to uncontrolled, triggered by psychedelic therapy (Foldi et al., 2020; Spriggs et al., 2021a, 2021b) could harness the reciprocal homeostatic and reward-processing cycles of the diet-MGB axis (Berding et al., 2021; Boscaini et al., 2022; Marx et al., 2021; Urrutia-Piñones et al., 2018). Similarly, given the overlapping relationship between diet, exercise and the MGB axis, psychedelic therapy-induced reappraisal of maladaptive physical activity patterns could be primed by optimal diet-MGB axis signalling before psychedelic therapy and then maintained after psychedelic therapy (Barton et al., 2018; Clarke et al., 2014; Clauss et al., 2021; O'Sullivan et al., 2015).

At this point, however, there is limited data on dietary and physical activity patterns pre- and post-psychedelic therapy (Teixeira et al., 2022). While self-reported survey data must be considered in the context of inherent self-selection and recall biases, there are some tentative indicators that diet, and exercise patterns may improve due to psychedelic experiences. 63% of participants endorsed “improved diet”, and 55% reported “increased exercise” in a survey primarily focussed on people who self-reported to have reduced (or stopped) alcohol consumption and misuse after a psychedelic experience (Garcia-Romeu et al., 2019). Similarly, 59% endorsed “improved diet”, and 58% endorsed “increased exercise” as a result of their psychedelic experience in a survey of people who self-reported to have stopped or reduced cannabis, opioid, or stimulant misuse after a psychedelic experience (Garcia-Romeu et al., 2020). It is also interesting to note that 96% of respondents who met criteria for substance use disorder before the psychedelic experience, decreased to 27% after the experience (Garcia-Romeu, et al., 2020).

A similarly cautious approach is warranted for the interpretation of a small open label study in TRD in which nearly half of the participants reported improvements in diet and exercise, and reductions in alcohol consumption (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016; Watts et al., 2017). While mild and transient GI disturbance can occur in approximately one fifth of people (Goodwin, et al., 2020), it is interesting to note one participant's account of the experience (Watts et al., 2017). This participant, who had pre-existing “stomach problems/food sensitivities”, re-appraised his relationship with food after psilocybin therapy, despite having no “lessons about diet” (Watts et al., 2017). While this participant reported changing his mindset and then his diet, during psilocybin dosing he initially experienced stomach pains and interpreted this as the psilocybin “going where it needed to go” (Teixeira et al., 2022; Watts et al., 2017).

Of course, each psychedelic therapy experience is complex, unique, and dependent on the individual's psycho-biologically encoded life narrative and priors. Yet, it raises interesting implications for conscious and unconscious information processing pathways between central and peripheral systems. The degree to which intent or conscious priors drive the self-reported improvements in diet and exercise in the aforementioned studies is not clear (Garcia-Romeu et al., 2020, 2019). But, as articulated by Teixeira and colleagues, this may open opportunities for behavioural therapy to further improve lifestyle factors (Teixeira et al., 2022). Moreover, psychedelic therapy induced expansion of the confines of the self to encompass an appreciation of the complex interconnectivity between micro and macro levels, inclusive of the microbiome, could potentially enhance the re-establishment and maintenance of diet-MGB and exercise-MBG axis patterns that are more homeostatically favourable to the individual.

The gut microbiota and adverse effects of psychedelicsWhen discussing side-effects, it is important to draw distinctions between clinical trials in which participants are thoroughly screened and supported and the potential side-effects from recreational use (Schlag et al., 2022). For example, most clinical studies exclude people with a family history of psychosis and major cardiac problems. Even with recreational use, reports of psychosis (Dos Santos et al., 2017), mania (Hendin & Penn, 2021), disturbed/unpredictable behaviour (Giancola et al., 2021; Honyiglo et al., 2019), serotonin syndrome (Schifano et al., 2021) and Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder (HPPD) (Litjens et al., 2014) are seemingly rare. Data from the 2017 Global Drug Survey of 9233 past year magic mushroom users, 0.2% of respondents reported having sought emergency medical treatment, mainly for anxiety/panic and paranoia/suspiciousness (Kopra et al., 2022). This was associated with inadequate set and setting and consumption with other substances (Kopra et al., 2022).

The emergence of clinical trial data is beginning to provide a clearer scientific picture of the side-effects of psilocybin therapy, though large studies with extended periods of follow-up are still lacking. Although limited by a relatively small sample of 89 healthy volunteers, there were no serious adverse effects and no treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) that led to study withdrawal in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a single oral dose of psilocybin 10 mg or 25 mg or placebo (Rucker et al., 2022). Preliminary data from the largest double-blind placebo-controlled dosing finding psilocybin therapy trial (n = 233) reported the most common side effects in the 25 mg group on dosing day were headache (24.1%), nausea (21.5%), dizziness (6.3%), and fatigue (6.3%), with 3.8% experiencing anxiety (Goodwin, et al., 2020). In the subgroup of TRD who continued SSRI's (n = 19), psilocybin was well-tolerated, with 11 (58%) participants reporting TEAEs, of which a majority (81%) were of mild severity (COMPASS, 2021). Given the role of serotonin in the stimulation of gut motility, it raises interesting questions of whether the diet-MGB axis may have subtle implications for the modulation of transient GI side-effects or autonomic nervous system effects in psychedelic therapy (Holze et al., 2021; Mörkl et al., 2022; Olbrich et al., 2021).

Psilocybiome: towards a personalised psychedelic treatmentThe operation of clinical psychiatry requires a reductionistic approach to demarcate subjective experiences and observable behaviour according to severity of impairment and distress, and the application of the best available evidence-based treatment strategies. However, this “discipline of the unexplained” (Kelly, 2021) will only fully be explicated by understanding the complex constellation of fluctuating transitions of information processing across all levels from micro to macro (Fried, 2022; Fried & Robinaugh, 2020; Topol, 2014). In keeping with this interconnected systems-based approach, the microbiome has been proposed as an additional transdiagnostic unit of analysis in the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework (Kelly et al., 2018). This evolving neuroscientific framework aims to integrate developmental processes and environmental inputs over the trajectory of the life course to determine the mechanisms underlying normal-range functioning, and then how disruptions correspond to dimensional psychopathology (Insel et al., 2010). It is hoped that the identification of targetable biosignatures that either cut across traditional disorder categories or that are unique to specific clinical phenomenona will lead to personalised treatment strategies and improve outcomes for people with mental health disorders (Krystal et al., 2020; Medeiros et al., 2020).

There is growing interest in incorporating the gut microbiome into personalised medicine schedules (Gupta et al., 2020). Gut microbiota signatures play a contributing role in the prediction of plasma glucose levels (Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose et al., 2019; Zeevi et al., 2015), glycaemic responses to exercise, (Liu et al., 2020) and lipid levels (Fu et al., 2015). Accruing data is starting to reveal the contributing influence of the gut microbiome on the variability of blood metabolites, also impacted by diet/lifestyle and genetic factors (Bar et al., 2020; Diener et al., 2022; Wilmanski et al., 2019). Microbial interventions also have an individualized impact on mucosal community structure and gut transcriptome (Johnson et al., 2019; Zmora et al., 2018). A recent example of a personalised microbiome approach, from a randomised, single-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of the prebiotic inulin in 106 people with obesity showed minimal changes in mood or cognition over placebo in the total group (Leyrolle et al., 2021). However, when stratified into responders and non-responders, according to differences between the positive and negative score in the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, responders (who had worse baseline mood scores) had increased baseline levels of Coprococcus, IL-8 and altered glucose homeostasis (Leyrolle et al., 2021). After treatment, increases in Bifidobacterium and Haemophilus were larger in the responder group, thus highlighting the intricacies and potential applications of personalised microbiome strategies (Leyrolle et al., 2021).

Future clinical studies could explore whether configurations of the microbiome architecture preferentially respond to psychedelic therapy. Previous studies have suggested that responses to standard antidepressant approaches are influenced by peripheral mediators such as immune (Drevets et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2019), kynurenine pathway metabolites (Bhattacharyya et al., 2019; Erabi et al., 2020) and metabolomic profiles (Caspani et al., 2021). As discussed throughout this review, the multi-system capabilities of the MGB axis interact with these pathways, and may play a role in unravelling the complex multi-factorial reasons for the continuum of responses to conventional antidepressant (Donoso et al., 2022) and psychedelic therapy, particularly in people with dysregulated neuroimmune, neuro-endocrine and metabolic profiles. Indeed, emerging preclinical data indicates that the gut microbiome is also associated with divergent responses to antidepressants (Duan et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021) (Table 1).

The individual variability in psychotropic drug response and disposition is also partially influenced by the gut microbiota (Clarke et al., 2019; Cussotto et al., 2021; Maini Rekdal et al., 2019; Vich Vila et al., 2020; Zimmermann et al., 2019), though the physiological implications for serotonergic psychedelics have yet to be meaningfully explored or defined. Preclinical studies of single and interval dosing regimens of serotonergic psychedelics across multiple dose ranges using GF, antibiotic, psychobiotic, FMT and dietary manipulation rodent models, together with measures of intestinal and BBB permeability and brain neurochemistry, could assess the mechanistic relevance of the MGB axis to the effects of psychedelics (Kelly et al., 2015; Knox et al., 2022).

Clinical psychedelic research is still at a relatively early stage, and it is essential to continuously improve the methodological rigour of clinical trials, with particular attention to challenges related to treatment masking/blinding, self-selection bias, and patient expectations (Aday et al., 2022; Hayes et al., 2022). Preliminary results from the largest and most methodologically rigorous trial to date in TRD, which compared single doses of 25 mg, 10 mg and 1 mg showed a 37% response rate (MADRS) at 3 weeks in the 25 mg group compared to 18% in the 10 mg group and 17% in the 1 mg group (Goodwin, et al., 2020). Interestingly, in a separate open label pilot study of TRD participants who received psilocybin (25 mg) along with their SSRI medications (of at least 6 weeks) showed a similar response rate of 42% at 3 weeks (COMPASS, 2021). It remains to be seen whether the incorporation of the diet-MGB and exercise-MGB axis into psychedelic therapy will improve these response rates.

Summary, conclusions, and perspectivesThe complex therapeutic mechanisms underlying psychedelic therapy traverse molecular, cellular, and network levels, under the influence of biofeedback signals from peripheral networks and the environment. Deciphering the clinical relevance of acute and transient changes in peripheral markers in healthy people and in those with dysregulated profiles associated with mental health disorders and their relationship with central markers in psychedelic therapy could lead to clinical benefits. As we have outlined, the gut microbial matrix influences overlapping neuroimmune, neuro-endocrine and transmitter signalling pathways of indirect applicability to the preparatory phase, the acute administration phase, and the integration phase of psychedelic therapy. This may occur even in the context of 1–3 dosing sessions.

Deeper mechanistic insights into the role of the MGB axis in modulating the effects of serotonergic psychedelics could be advanced by various microbiome manipulation approaches in rodent models. Exploration of reciprocal host-microbiota-psychedelic interactions, including diet-MGB and exercise-MGB axis interactions, perhaps amplified by components of behavioural therapy and digital health platforms, could, over the course of psychedelic therapy and into the longer-term, open avenues to counteract the negative consequences of stress-related feedforward cycles of maladaptive behavioural patterns to enhance therapeutic response rates.

Taken together, the MGB axis holds promise as an adjunctive modifiable translational target across the trajectory of psychedelic therapy, which in conjunction with other strategies could be leveraged to influence the continuum of therapeutic responses and improve outcomes in psychedelic therapy. Longitudinal clinical studies exploring the MGB axis over the trajectory of psychedelic therapy and into the long term, using different psychedelic doses compared to placebo, with central markers of brain activity, and then investigating various MGB axis modulation strategies (diet, probiotics, prebiotics, and antibiotics) particularly in the preparatory and pre-dosing phase, could help define whether the gut microbiome is a possible mediator and thus clinically relevant to the effects of psychedelics.

From a mindful microbes perspective, it is interesting to note that it has taken 350 years from the first human observation of microbes (Lane, 2015) to the current burgeoning implementation of the microbial system into the complex algorithms attempting to predict human emotion, cognition, and behaviour. Elucidating the precise constellation of molecular configurations and associated information signalling pathways of the psilocybiome, as an example of systems interconnectivity, will require an integrated multiomics approach. The future integration of the gut microbiome in studies implementing a dimensional approach would push the frontiers of an interconnected precise-personalised-systems based psychedelic therapy paradigm and further open the “doors of perception”.

LimitationsThis is a narrative review exploring the potential role of the MGB axis in psychedelic therapy.

FundingJK was the sub-PI on the COMPASS trials (COMP 001, 003, 004) in Ireland. JFC & TGD have research funding from Dupont Nutrition Biosciences APS, Cremo SA, Mead Johnson Nutrition, Nutricia Danone. JFC, TGD & GC have spoken at meetings sponsored by food and pharmaceutical companies. VO'K was supported through HRB Grant Code: 201,651.12553 and the Meath Foundation, Tallaght University Hospital. VO'K was the Principal Investigator (PI) on the COMPASS trials (COMP001, 003, 004) in Ireland.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJohn R. Kelly: Writing – original draft. Gerard Clarke: Writing – review & editing. Andrew Harkin: Writing – review & editing. Sinead C. Corr: Writing – review & editing. Stephen Galvin: Writing – review & editing. Vishnu Pradeep: Writing – review & editing. John F. Cryan: Writing – review & editing. Veronica O'Keane: Writing – review & editing. Timothy G. Dinan: Writing – review & editing.

We would like to acknowledge Paul Quinlan who designed Fig. 1 and Christopher Connolly for his review of the manuscript.