We propose a novel privacy-preserving security solution for cloud services. Our solution is based on an efficient non-bilinear group signature scheme providing the anonymous access to cloud services and shared storage servers. The novel solution offers anonymous authenticationfor registered users. Thus, users' personal attributes (age, valid registration, successful payment) can be proven without revealing users' identity, and users can use cloud services without any threat of profiling their behavior. However, if a user breaks provider's rules, his access right is revoked. Our solution provides anonymous access, unlinkability and the confidentiality of transmitted data. We implement our solution as a proof of concept applicationand present the experimental results. Further, we analyzecurrent privacy preserving solutions for cloud services and group signature schemes as basic parts of privacy enhancing solutions in cloud services. We compare the performance of our solution with the related solutionsand schemes.

Cloud services are becoming indisputable parts of modern information and communication systems and step into our daily lives. Some cloud services such as Amazon's Simple Storage Service, Box.net, Cloud Safe etc. use user identity, personal data and/or the location of clients.Therefore, these cloud computing services open a number of security and privacy concerns. The current research challenge in cloud services is the secure and privacy-preserving authentication of users. Users, who store their sensitive information like financial information, health records, etc., have a fundamental right of privacy. There are few cryptographic tools and schemes like anonymous authentication schemes, group signatures, zero knowledge protocols that can both hide user identity and provide authentication. The providers of cloud services need to control the authentication process to permit the access of only valid clients to their services. Further, they must be able to revoke malicious clients and reveal their identities.

In practice, hundreds of users can access cloud services at the same time. Hence, the verification process of user access must be as efficient as possible and the computational cryptographic overhead must be minimal.

We propose a novel security solution for cloud services that offers anonymous authentication based on group signatures. We aim mainly on the efficiency of the authentication process and user privacy. Our solution also provides the confidentiality and integrity of transmitted data between users and cloud service providers. Moreover, we implement our solution as a proof-of-concept application and compare the performance of our solution with related schemes. Our results show that our solution is more efficient than the related solutions.

The paper is organized as follow: The next section presents the related work. Then, we analyse cryptographic privacy-preserving schemes used in cloud computing. In section 4, we describe group signatures. In section 5, wepresent our solution and we introduce our novel privacy-preserving cryptographic scheme for cloud services in section 6. Section 7 contains our experimental results and the performance analysis and comparison. Finally, the conclusion of our work is presented.

2Related workPrivacy-preserving cloud computing solutions have been developed from theoretical recommendations to concrete cryptographic proposals.

There are many works which deal with general security issues in cloud computing but only few works deal also with user privacy.

The authors [1] explore the cost of common cryptographic primitives (AES, MD5, SHA-1, RSA, DSA, and ECDSA) and their viability for cloudsecurity purposes. The authors deal with the encryption of cloud storage but do not mention privacy-preserving access to a cloud storage.

The work [2] employs a pairing based signature scheme BLS to make the privacy-preserving security audit of cloud storage data by the Third Party Auditor (TPA). The solution uses batch verification to reduce communication overhead from cloud server and computation cost on TPA side.Further, the paper [3] introduces the verification protocols that can accommodate dynamic data files. The paper explores the problem of providing simultaneous public auditability and data dynamics for remote data integrity check in Cloud Computing in a privacy-preserving way.These solutions [2] and [3] provide privacy-preserving public audit but do not offer the anonymous access of users to cloud services.

The work [4] establishes requirements for a secure and anonymous communication system that uses a cloud architecture (Tor and Freenet). Nevertheless, the author does not outline any cryptographic solution. Another non-cryptographic solution ensuring user privacy in cloud scenarios is presented in [5]. The authors propose a client-based privacy manager which reduces the risk of the leakage of user private information.In the paper [6], authors use a non-cryptographic approach to obtain the benefits of the public cloud storagewithout exposing the content of files. The approach is based on redundancy techniques including an information dispersal algorithm (IDA). Nevertheless, these solutions do not protect against the linkability of user sessions which can cause unauthorized user profiling.

Jensen et al. [7] propose an anonymous and accountable access method to cloud based on ring and group signatures. Nevertheless, their proposal uses a group signature scheme [8] which is inefficient because the signature size grows with the number of users.

The work [9] presents a security approach which uses zero-knowledge proofs providing user anonymous authentication. The main drawback of the proposal is a large communication overhead between a user and a cloud server due to the Fiat-Shamir identification scheme [10]. In the work [11], the author uses the CLsignature scheme [12] and zero-knowledge proofs of knowledge to achieve user's anonymous access to services like digital newspapers, digital libraries, music collections, etc.

The work [13] presents a cryptographic scheme to ensure anonymous user access to information and the confidentiality of sensitive documents in cloud storages. The work[14]deals with anonymity and unlinkability in cloud services by provided group signature schemes[15]. In the next section, we analyze the solutions [11], [13] and [14].

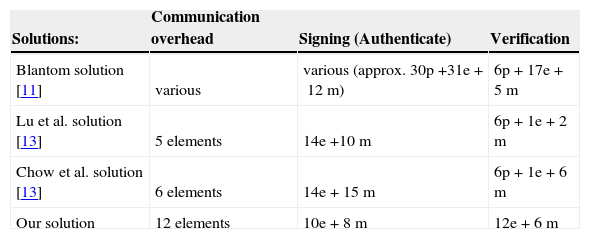

3Performance analysis of cryptographic privacy-preserving solutions used in cloud computingIn this section, we investigate the current cryptographic solutions which provide the anonymous or pseudonymous access to cloud services and shared storages. We aim on the authentication phases used in privacy-preserving cloud services. In the following performance analysis, we take into account only expensive operations like bilinear pairings (p), modular exponentiation (e) and multiplication (m). According to the results of works [16], [17], we omit the fast operations like addition, subtraction or hash functions which have a minimal impact on the overall performance. The times of expensive pairing operations have been measured for example in [25].

Table 1 shows the performance analysis of the Blantom solution [11], the Lu et al. solution [13], the Chow et al. solution [14] and our scheme described in Section6. Blantom in [11] proposes a solution using the CL signatures [12]. To establish anonymous authentication, the CL signature is combined with a Zero Knowledge Proof of Knowledge (ZKPK) protocols. The computational complexity of Blantom solution depends on the subscription type and is variable. Lu et al. [13] propose a pairing-based cryptographic scheme ensuring anonymous authentication of users accessing cloud services. A user has to sign a challenge received from a server and then he/she sends it back to verify it. Chow et al. [14]employ group signature schemes proposed by Boyen and Waters in [15]and [18](BW schemes). The BW scheme [18]is used to make a group signature which provides the anonymous authentication of users. Nevertheless, these solutions have 6 pairing operations in verification. In the next section, we present our solution that does not use expensive pairing operations.

4Group signatures as a basic part in privacy enhancing cloud servicesGroup signature schemes are used in many privacy enhancing cryptographic protections that are applied in cloud services. Group signatures were introduced by Chaum and Heyst [8] in 1991. Their main purpose is to allow members of a group sign messages on behalf of the group. Every group member can sign a message by own group member secret key gsk[i] that is usually issued by a group manager. A verifier checks the validity of the signature with a group public key gpk. The verifier is able to verify that the signer is indeed the member of the group while the signer's identity is not released. The identities of the members are traceable only in certain circumstances, e.g. breaking the rules.

Revocation can be done by the group manager or a revocation manager who owns group manager's secret key gmsk. The group signature schemes usually employ the following entities:

- •

Group manager – this entity adds group members into a group, and generates and issues the secret keys of group members.

- •

Revocation manager – this entity disclosures the identity of dishonest members.

- •

User – a group member who owns the group member secret key gsk[i]. The user can sign a message on behalf of the group.

- •

Verifier – this entity verifies the validity of the signature by using the group public key gpk.

Currently, there are many variants of group signatures schemes which differ mainly in their properties such as the level of anonymity, security, efficiency and the length of signature. Group signatures can be understood as a subset of attribute authentication systems, which contain only one attribute representing a membership in a group. Group signatures schemes usually provide the following properties:

- •

Unforgeability – only an unrevoked group member can create a valid signature on behalf of the group.

- •

Anonymity – a verifier is not able to determine the identity of a signer.

- •

Complete anonymity – if an attacker obtains a valid signature and knows gpk and all keys of group members' gsk[i], he is not able to determine the identity of a signer.

- •

Traceability – all members can be tracked by the group manager or the revocation manager by member's signed message.

- •

Unlinkability- a verifier and other members are not able to link two signatures which have been signed by one member of the group.

- •

Coalition-resistance – it is impossible to create a valid signature by a subgroup of users.

- •

Exculpability – even group manager is not able to create a valid signature of a group member.

- •

Correctness – every correct signature of the group member has to be always accepted during verification.

- •

Revocation-a revoked member is not able to create valid signatures on behalf of the group.

- •

Differentiation of group members – all members of the group must have a different gsk[i].

- •

Immediate-revocation – if a group member is revoked, his capability of creating the group signatures is disabled immediately.

In this chapter, we introduce our security solution for privacy-preserving cloud services. We outline our system model depicted in Figure 1, security requirements, cryptography background and cryptographic protocols.

5.1System ModelOur solution consists of three fundamental parties:

Cloud Service Provider (CSP). CSP manages cloud services and shared storages. CSP isusually a company which behaves as a partly trusted party. CSP provides cloud services, authenticates users when they access a cloud service. CSP also issues access attributes to users. Nevertheless, when CSP needs to revoke and identify a malicious user then CSP must collaborate with a revocation manager.

Revocation Manager (RM). RM is a partly trusted party, e.g. government authority, who decides if the revocation of a user identity is rightful or not. Only the cooperation between CSP and RM can reveal the user identity. RM also cooperates with CSP during user registration when the user's access attributes are issued.

User (U). U is an ordinary customer who accesses into a cloud and uses cloud services, shared storages, etc. Users are anonymous if they properly follow the rules of CSP. To increase security, users use tamper-resistant devices or protected local storages.

5.2RequirementsOur solution provides the following security requirements:

- •

Anonymity. Every honest user stays anonymous when uses cloud services. User identities are hidden if users behave honestly and do not break rules.

- •

Confidentiality. Every user's session to CSP is confidential. No one without a secret session key is able to obtain data transmitted between U and CSP.

- •

Integrity. Data sent in user's session cannot be modified without a secret session key

- •

Unlinkability. The user's sessions to cloud services are unlinkable. No one besides CSP collaborating with RM is able to link two or more sessions between a certain U and CSP.

- •

Untraceability. Other users are unable to trace user's authentication and concrete users' communication.

- •

Revocation. Every user can be revoked by the collaboration of CSP and RM.

In our solution, we use discrete logarithm commitments described in the work [19]. We have transformed the scheme [19] into a group signature scheme mode.Further, the solution employs Σ-protocols [20]to prove of discrete logarithm knowledge, representation and equivalence [21]. To revoke a user, we use the Okamoto-Uchiyama Trapdoor One-Way Function described in [22]. For more details about the used basic cryptographic blocks see prior works [19] and [23].

6Ourproposed protocolOur protocol consists of five phases: initialization, registration, anonymous access, secure communication and revocation. The basic principle of the proposed protocol is depicted in Figure 2.

• {tc “1 The Basic Principle of the Proposed Protocol.” \f f}

6.1InitializationThe initialization phase is run by Cloud Service Provider (CSP) and Revocation Manager (RM). CSP generates a group H defined by a large prime modulus p, generators h1, h2 of prime order q and q|p - 1. CSP generates a RSA key pair and stores own private key KCSP.

M generates a group G defined by a large modulus n=r2s where r=2r′+1, s=2s′+1 and r,s,r′,s′ are large primes. RM also generates a generator g1∈Rℤn* of orderord(g1modr2) = r(r - 1) in ℤr2* and ord(g1) = rr′s′ in ℤn* and randomly chooses secret values S1,S2,S3. RM computes authentication proof Aproof=g1S1mod n which is public and common for all entities in system. In our solution, the RM is able to issue more types of authentication proofs Aproof1…AproofN derived from S11…S1N that are related to different user rights in cloud services.

Finally, RM computes generators g2=g1S2mod nandg3=g1S3mod n and stores secret valuesr,sas revocation key KRK.

All public cryptographic parameters q,p,n,g1,g2,g3,h1,h2,Aproof are published and shared.

6.2RegistrationIn the registration phase, a user registers and requests a user master key which they use in anonymous access to cloud services.

Firstly, U must physically register on CSP. CSP checks user's ID. Then, U generates secret values ω1,ω2 and makes the commitment: CCSP=h1ω1h2ω2mod p. U digitally signs Ccsp, e.g. by RSA, and sends this signature Sigu(CCSP) with the construction of correctness proof PK{ω1,ω2: CCSP = h1ω1h2ω2 to CSP, by notation of Camenisch and Stadler [21]. CSP checks the user's proof and the signature. Then, CSP stores the pairCCSP,Sigu(CCSP), signs the commitment SigCSP(CCSP)and sends it back to U.

Secondly, U requests a user master key from RM. U computesA′proof=g1ω1g2ω2 mod n and sends it with CCSP,SigCSP(CCSP) and the construction of correctness proof PK{ω1,ω2:CCSP=h1ω1h2ω2∧A′proof=g1ω1g2ω2 to RM. RM checks the proof, CSP's signatureSigcsp(CCSP) and computes a secret contribution ωRM such that Aproof=g1ω1g2ω2g3ωRM mod n holds. After this step, U obtains own user master key Ku which is triplet(ω1,ω2,ωRM). U gets value ωRM only with cooperation with RM which knows the factorization of n. To prevent the collusion attack, user's ω1,ω2 is not visible outwardly to a user because ω1,ω2 is stored in a tamper-resistant memory. This device which stores the user secret key should be also protected against a key estimation by side channel attacks, such as in [24]. Further, U cannot make own user master key because only RM knows KRK. Any honest user can repeat the request for the user master key or demand other authentication proofs if CSP agrees with that.

6.3Anonymous AccessIn this phase, the i-th user Ui anonymously accesses Cloud Service Provider (CSP). This phase consists of two-messages used to authenticate Ui and establish a secret key between Ui and CSP.

- •

Ui generates a random value andom∈R{0,1}lsym. The parameter lsym denotes the size of a shared secret key for the symmetric cipher.

- •

Ui encryptsrandom by the RSA public key of CSP.

- •

The encrypted Enc_PK_server(random) is signed by the Auth_proof_sign algorithm in the group signature modewhich ensures user anonymous authentication. We assume that cryptographic parameters such as q,p,n,g1,g2,g3,h1,h2 and authentication proof Aproof=g1ω1g2ω2g3ωRM mod n are made public and ℋ is a secure hash function. To prove the knowledge of the secret user key and signrandom, Ui performs the Auth_proof_sign algorithm:

Finally, the signature elements A,A¯,Aproof¯C1,C2,C1¯,C2¯,z1,z2,z3,zs, Enc_PK_server(random) are sent to CSP as a request message.

- •

CSP verifies the signed request message that consists of the signature elements: Enc_PK_server(random),A,A¯,Aproof¯,C1,C2,C1¯,C2¯,z1,z2,z3,zs,. Then, CSP does the Auth_proof_verify algorithm:

If above equations hold then CSP continues in the next step. Otherwise, CSP stops the algorithm.

- •

CSP decrypts a value Enc_PK_server (random) by its RSA private key to obtain random.

- •

CSP randomly generates shared secret key K_sym and uses eXclusive OR (XOR) function to compute random⊕K_sym.

- •

CSP sends a response message (random⊕K_sym) back to Ui.

If the anonymous access phase is successful, the user Ui can upload and download data from CSP. Data confidentiality and integrity are secured by a symmetric cipher. We propose to use AES which is well know cipher and is supported by many types of software and hardware platforms. To encrypt and decrypt transmitted data, Ui and CSP use the AES secret key K_sym established in the previous phase.

6.5RevocationDepending on the case of rule breaking, the revocation phase can revoke a user and/or user anonymity.

If users misuse a cloud service, they get revoked by RM. Because RM knows the factorization of n, RM is able to extractωRM. Firstly, RM extracts the random session value KS from C2 and the secret RM contribution value ωRM from C1.

Then, RM publishes ωRM into a public blacklist. If the user uses revoked key then the equation C1≡C2ωRMmodn holds and the user access to cloud services is denied.

If a malicious user breaks the rules of CSP, this user can be identified by the collaboration of RM and CSP. Firstly, RM extracts ωRM from the suspected session received by CSP. Then, RM finds the corresponding CCSP in the database. If CSP provides to RM the explicit evidence of user's breach, then RM sends CCSP to CSP. CSP is able to open the identity of a user from database but only with RM's help.

7Experimental resultsIn this section, we outline the experimental results of our solution. We compare our solution with related solutions and output the performance evaluation.

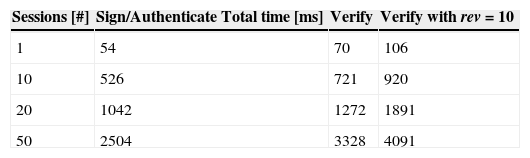

7.1Performance Evaluation of Our SolutionWe have implemented our proposed solution in JAVA. In practice, we expect that U as an end node uses devices with reasonable computational power such as a personal computer, a laptop, a tablet or a smartphone. On the other hand, we assume that CSP keeps servers with sufficient computational capacity to ensure hundreds sessions with end nodes in real time. We have tested our solution on a machine with Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU X3440 @ 2.53GHz, 4 GB Ram. In our a proof-of-concept implementation, we choose the 1024-bit length of modulo. The main important part of our solution is the Anonymous Access phase. In this phase, a user (U) communicate with a Cloud Service Provider (CSP). The computation process on the user side is marked as the Sing/Authenticate process. The computation process on the CSP side is marked as the Verify process. We have measured the total time of the Sing/Authenticate process and the Verify process. In the Verify process, Table 2 shows two scenarios: with an empty black list and with the black list that contains the revoked values rev=10. The influence of the size of blacklist on the total time of the Verify process is depicted in Figure 3.

We compare our Anonymous Access phase with the authentication phase of related solutions: Blantom solution [12], Lu et al. solution [13] and Chow et al. solution [14]. To ensure objectivity, we compare the number of atomical cryptographic and math operations for each solution.

Firstly, we compare the Sign/Authenticate process that runs on the user side. In the Sign/Authenticate process, Lu et al. solution [13] takes 14 exp + 10mul, Chow et al. solution [14] takes 14 exp + 15mul and Blantom's solution [12]takes tens of pairing and exponentiation operations. The number of operations in Blantom's solution [12] depends on the subscription type and is variable. Our Sign/Authenticate process takes only 8 exp + 5mul and is the most efficient from compared solutions.

The Verify process on the CSP side has 10 exp + 6mul in our solution. We emphasize that our solution has 0 paring operations. Lu et al. solution [13], Chow et al. solution [14] and Blantom solution [12] are pairing based and contain 6 pairing operations in the Verify process. Figure 4 depicts the performance of the verifyprocess of our and related solutions. The verify process of our solution is more efficient than related solutions in this comparison and takes only 28 % of the total time of Lu et al. solution [13] or Chow et al. solution [14].

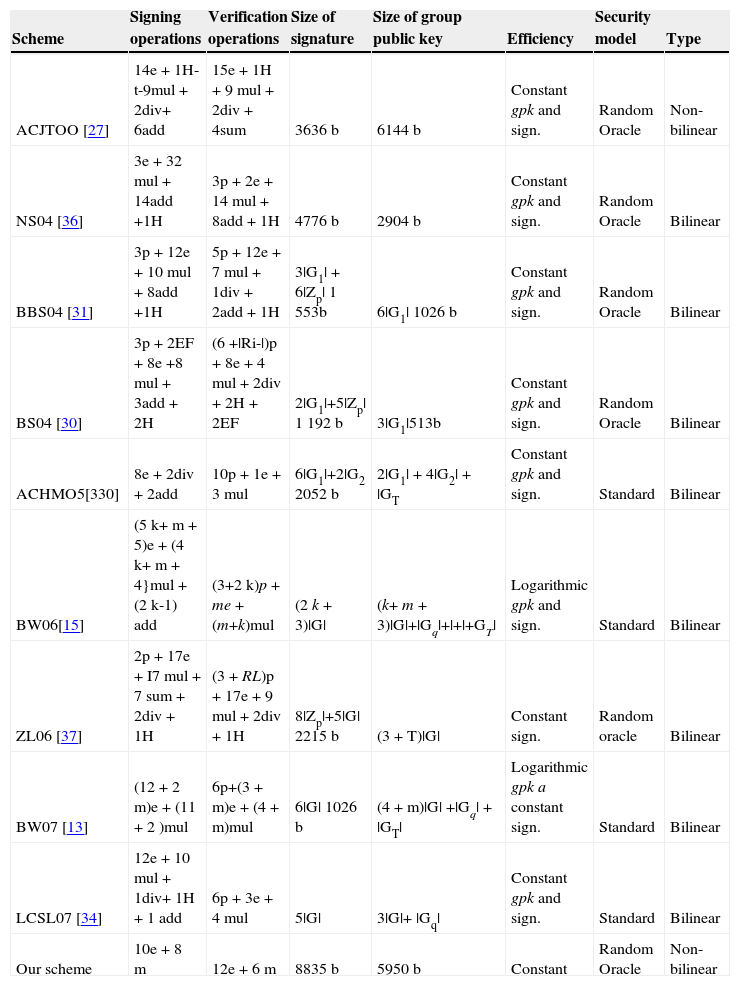

7.3Comparison of our group signature scheme with the related workIn this section, we analyze group signature schemes from open literatureandcompare them with ourgroup signature schemeused in our proposal, see Table 3. In the following part, we analyze group signature schemes and describe their evolution.

Comparison of Group Signatures Schemes with Our Solution.

| Scheme | Signing operations | Verification operations | Size of signature | Size of group public key | Efficiency | Security model | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACJTOO [27] | 14e+1H-t-9mul + 2div+ 6add | 15e+1H + 9mul + 2div + 4sum | 3636 b | 6144 b | Constant gpk and sign. | Random Oracle | Non-bilinear |

| NS04 [36] | 3e+32mul + 14add +1H | 3p+2e + 14mul + 8add + 1H | 4776 b | 2904 b | Constant gpk and sign. | Random Oracle | Bilinear |

| BBS04 [31] | 3p+12e + 10mul + 8add +1H | 5p+12e + 7mul + 1div + 2add + 1H | 3|G1| + 6|Zp| 1 553b | 6|G1| 1026 b | Constant gpk and sign. | Random Oracle | Bilinear |

| BS04 [30] | 3p+2EF + 8e +8mul + 3add + 2H | (6 +|Ri-|)p + 8e+4mul + 2div + 2H + 2EF | 2|G1|+5|Zp| 1 192 b | 3|G1|513b | Constant gpk and sign. | Random Oracle | Bilinear |

| ACHMO5[330] | 8e+2div + 2add | 10p+1e + 3mul | 6|G1|+2|G2 2052 b | 2|G1| + 4|G2| + |GT | Constant gpk and sign. | Standard | Bilinear |

| BW06[15] | (5k+ m + 5)e + (4k+ m + 4}mul + (2k-1) add | (3+2k)p + me + (m+k)mul | (2k + 3)|G| | (k+ m + 3)|G|+|Gq|+|+|+GT| | Logarithmic gpk and sign. | Standard | Bilinear |

| ZL06 [37] | 2p+17e + I7mul + 7 sum + 2div + 1H | (3 + RL)p + 17e + 9mul + 2div + 1H | 8|Zp|+5|G| 2215 b | (3 + T)|G| | Constant sign. | Random oracle | Bilinear |

| BW07 [13] | (12+2m)e + (11 + 2)mul | 6p+(3 + m)e + (4 + m)mul | 6|G| 1026 b | (4 + m)|G| +|Gq| + |GT| | Logarithmic gpk a constant sign. | Standard | Bilinear |

| LCSL07 [34] | 12e+10mul + 1div+ 1H + 1 add | 6p+3e+4mul | 5|G| | 3|G|+ |Gq| | Constant gpk and sign. | Standard | Bilinear |

| Our scheme | 10e+8m | 12e+6m | 8835 b | 5950 b | Constant | Random Oracle | Non-bilinear |

Group signatures were introduced and first four schemes were presented in the work CHH91[8] in 1991. The main disadvantage of these schemes is long sizes of a group public key gpk and a signature. Sizes depend on the number of members in a group. If a new member is added to the group, it is necessary to modify gpk. These deficiencies are very impractical for large groups of members. Therefore, these schemes are not suitable in cloud services. In the work CS97[26], published in 1997, authors propose a scheme which using the constant size of gpk and signatures. New members can be added to the group without the need to generate a new key pair gpk and gsk[i]. The paper ACJT00[27], introduced in 2000, presents an efficient scheme which is resistant of coalition, i.e. it is impossible for a subset of the group members including the group manager to create a valid signature. The disadvantage of the scheme is missing of the revocation of group members and prevention to a revoked member generates the valid signatures on behalf of the group. The work AST02 [28], published in 2002, is based on the scheme ACJT00 [27] and adds the revocation of the group members without using a time stamp. This approach keeps a constant length of a signature, i.e. this length does not increase linearly with the number of revoked members. However, the scheme has more operations in signing and verification phases than related schemes.The scheme TX03 [29], published in 2003, provides the dynamic revocation of group members. Revoked members are no longer able to create a valid signature. On the other hand, the disadvantage is that, gpk has to be recalculated when a member is added to the group or remove from the group. This approach is highly inefficient in the real time systems working with large groups. The schemes BS04 [30] and BBS04 [31], published in 2004, allow to create short group signatures. These schemes are based on bilinear maps and produce short signatures which are suitable in systems where bandwidth is restricted.Unless as the previous schemes that are secure in the random oracle model, the scheme BMW03 [32], introduced in 2003, is secure in the standard model. Nevertheless, the scheme is designed for the static and small groups of users. Therefore, this scheme is not proper for cloud services.

The scheme ACHM05 [33], introduced in 2005, is provable secure in the standard model and works with dynamic groups. The scheme provides anonymity, unforgeability, untraceability and exculpability, and is secure against a non-adaptive adversary who does not have gsk[i] of group members. The scheme BW06 [15] provides the provable security in the standard model. But, the size of the signature depends on the size of the group. The newer scheme BW07 [18], introduced in 2007, produces shorter and almost constantly sized signature in comparison with the previous schemes. The length of a signature increases logarithmically as the size of the group.

The scheme LCSL07 [34] produces short signatures with constant lengths. This scheme offers full anonymity and full traceability, and the public key and signatures are shorter than in the previous schemes. The scheme G07 [35], published in 2007, ensures full anonymity in the standard model. The scheme is based on bilinear groups and produces the constant lengths of keys and signatures. The scheme also supports the dynamic addition of new members to the group.

We compare our scheme with the group signature schemes in Table 3. Our scheme is based on non-bilinear assumptions and has only 10 exponentiations and 8 multiplications in the verification phase. Our scheme clearly outperforms the related schemes. The operations are abbreviated as bp- bilinearpairings, e - exponentiation, mul- multiplication, div - division, add - addition (subtraction), H-hash, k- length of identities in bits, m - length of message in bits, RL- members in a revocation list, EF - efficiently computable isomorphism from G2 to G1, T - the total time of a period.

8ConclusionIn this paper, we present our novel security solution for privacy-preserving cloud services. We propose the non-bilinear group signaturesscheme to ensure the anonymous authentication of cloud service clients. Our novel solution offers user anonymity in the authentication phase, data integrity and confidentiality and the fair revocation process for all users. Users use tamper resistant devices during the generation and storing of user keys to protect against collusion attacks.

Our authentication phase, which is based on the non-bilinear group signature scheme, is more efficient than related solutions on the client side and also on the server side due to missing expensive bilinear pairing operations and fewer exponentiation operations.Thus, cloud service providers using our solution can authenticate more clients in the same time. We also analyze related group signature schemes. The group signature scheme used in our solution is more efficient than related group signature schemes in the verification phase and provides the efficient privacy-preserving access to cloud services.

This research work is funded by project SIX CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0072; the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic projects TA02011260 and TA03010818; the Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Czech Republic project FR-TI4/647.