The scenario of the health system can develop physical and emotional impacts on health professionals, due to work overload and failure to manage the system. It is necessary to consolidate the theory that the safety of care provided by health services is affected by organizational conditions. The aim of this study is to assess whether safety culture is related to job satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and burnout syndrome among hospital professionals.

Materials and methodsThis is an analysis with structural equation modeling, conducted in a teaching hospital in Brazil. Data collection was made via psychometric instruments, which sought to analyze job satisfaction (Job Satisfaction Survey), depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire), burnout syndrome (Maslach Burnout Inventory), as well as the relationship between this factors and patient safety culture (Safety Attitudes Questionnaire). The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) were used for analysis.

ResultsA higher work satisfaction was associated with a higher perception of safety culture (r=0.69; P<0.001). Depressive symptoms and burnout dimensions showed an inverse relationship with the safety culture (P<0.05). PLS-SEM enabled us to understand the behavior of this association. Thus, satisfaction at work and the absence of burnout proved to be predictive factors for the implementation of an ideal patient safety culture (P<0.001).

ConclusionsPatient safety culture is related to job satisfaction and burnout among hospital professionals. These findings suggest that the psychosocial work environment influences the quality of care provided.

Despite insufficient approaches and lack of data on the subject, adverse events related to hospital care (such as medication errors, surgical errors, hospital-acquired infections, among others) are becoming increasingly concerning in Brazil, reaching records of 104.187–434.112 deaths per year. It is estimated that two people die every three minutes as a result of these episodes.1

Investing in a safety culture is essential to avoid these events, as a safety culture is essential for building a safe health system. The safety culture is based on the promotion of preventive procedures aimed at beneficial outcomes, awareness of the importance of safety principles and professional interaction with mutual trust.2,3

However, the safety culture is impaired in environments where professionals do not receive support and are exposed to a high emotional burden, high demand of work and intense responsibilities. In the long term, these negative aspects affect the personal fulfillment and mental health of professionals.4

Job satisfaction is made up, among other aspects, of incentives, rewards, opportunities, good institutional performance, good relationship between the work team and humanized supervision. Health care workers often experience an imbalance related to these aspects, thus developing dissatisfaction.5

In situations with increased workload and emotional distress, this can affect the physical and psychological health of professionals in health institutions and negatively impact the care provided to users of these services.6

The need to consolidate the theory that healthy work environments provide quality health care services via academic studies is evident. Research suggests that the well-being of the work team prevents adverse events.7

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between patient safety culture, job satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and burnout syndrome among hospital health professionals.

Material and methodsStudy designThis is a cross-sectional study with structural equation modeling analysis, conducted between August and November 2016 in a teaching hospital in Brazil. The highly complex characteristics of the selected hospital are predominant in this country.

SettingThe research was carried out in a highly complex hospital and linked to the Brazilian public health system. According to the definition adopted in Brazil and according to the principles of the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS), high complexity refers to high technology and high cost, highlighting procedures and/or qualified services that are available to the population and, in addition, it is integrated with care basic healthcare and of medium complexity.

The hospital is characterized by its emergency and urgent care, specialized in high complexity assistance in orthopedics, traumatology, and nephrology, as well as care of high risk pregnancies. The hospital had 174 beds and 16 beds in intensive care unit.

The monthly mean of admissions was 640 and a men of 360 surgeries has been done monthly. The hospital mortality was at 6% and institutional mortality rate was at 5%.

ParticipantsThe participants were selected by random sampling from the list of professionals obtained from the institution's human resources department. Inclusion criteria were: professionals with an employment relationship for three months or longer and who consented to participate in the study. Individuals under notice, on vacation, on medical leave, or workers from third-party companies were excluded.

VariablesSociodemographic, occupational and economic characteristics were analyzed by the instrument. The items, which were self-reported by the participants, were: gender (female or male), age (in years and categorized under the ranges 18–35, 36–50 or ≥51), profession or field of activity (member of technical and administrative support or health professional), interaction or direct contact with the patient (no or yes), socioeconomic class (A, B, C or D/E), time working in the area (in years, categorized under the ranges <1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–10, 11–20 or ≥21) and level of education (incomplete secondary education, complete secondary education or higher education).

The primary outcome of the study was the perception of patient safety culture. Job satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and burnout syndrome were measured as independent variables.

Data sources and measurementAfter signing the informed consent form, data were collected via an electronic questionnaire filled out by the participant in a tablet.

The Brazilian Criteria was used to assess the economic classification,8 an instrument analyze housing conditions, asset ownership, access to public services, and education level of the head of household. The household's monthly income in Brazilian real (BRL) was estimated. The currency was converted to United States dollars (USD) with the values provided by the Central Bank of Brazil (1 USD=3.23 BRL). Therefore, monthly incomes were established: Class D-E 768 BRL (238 USD), Class C 1625–2705 BRL (503–838 USD), Class B 4852–9254 BRL (1503–2866 USD), and Class A 20,888 BRL (6468 USD) or above.

The validated Portuguese version of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ)9 was applied in order to assess the perception of patient safety culture. This questionnaire is considered of high sensitivity in assessing individual attitudes,10 in addition to being indicated by the European Network for Patient Safety for the implementation of safety culture.11 It consists of 41 questions distributed around six domains: teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, stress recognition, perceptions of unit and hospital management, and working conditions. Answers were informed via a five-point Likert scale and converted to a score from 0 to 100. A total score≥75 demonstrates an ideal agreement of professionals with hospital attributes for patient safety, which is a positive indicator.12

The Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS)13 was used to measure job satisfaction, the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS)14 to identify burnout syndrome, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)15 to assess depressive symptoms. The procedure for analyzing these variables has already been described elsewhere in our study.16

Bias controlIn order to emphasize its importance and to disseminate the study's aim among all the work teams, the research was presented to the management group and to the leaders of the hospital. In this way we try to provide autonomy and prevent any discomfort in order for professionals to express their perceptions without fear of punishment.

To ensure comfort and confidentiality for participants, data collection took during the most opportune moment for the recruited employee. The tablet was handed to the participant, while the researcher remained available in another previously communicated location, to clarify any doubts during the process.

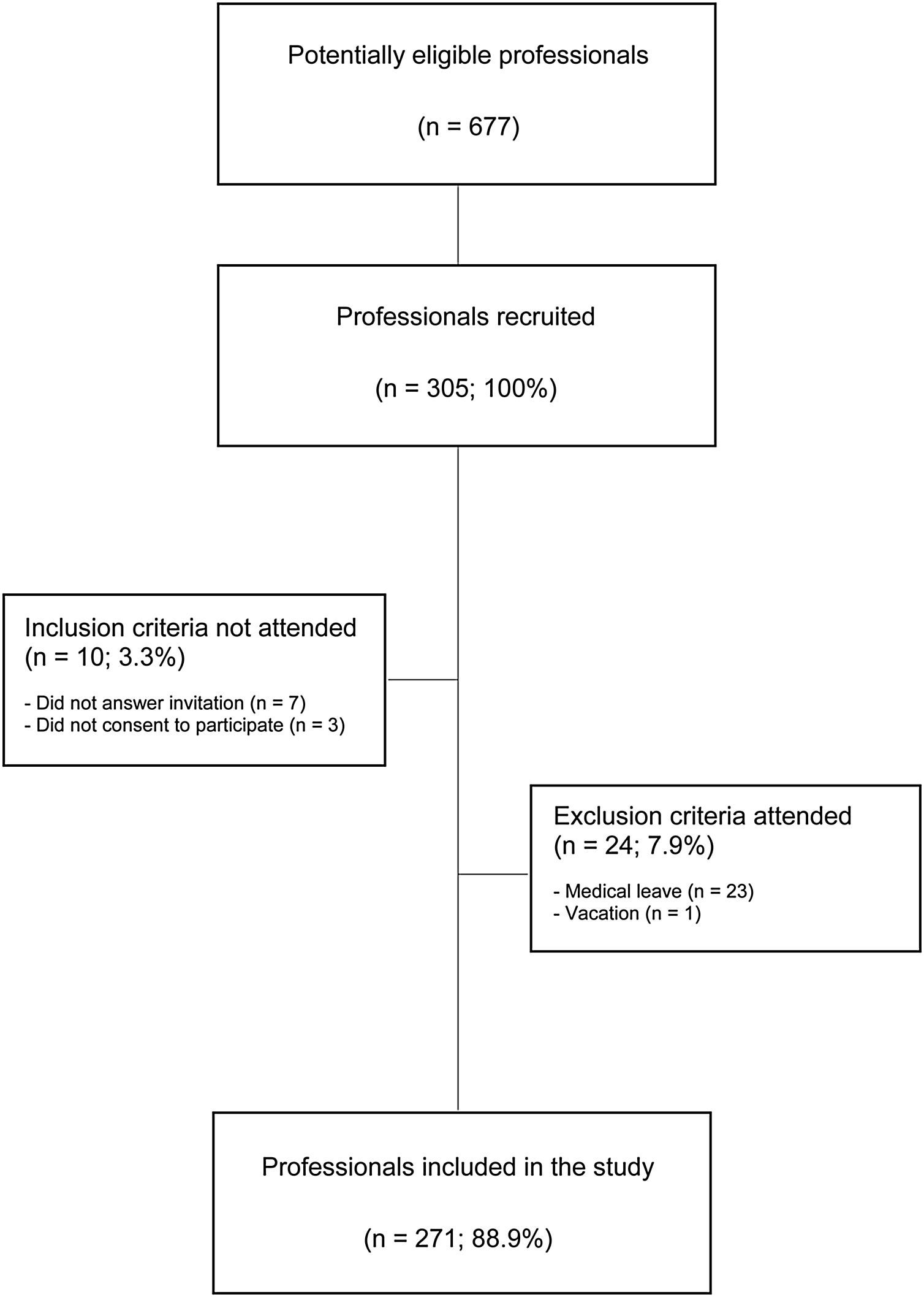

Study sample sizeWe calculated the number of participants (246, 95% CI) from the total number of workers in the hospital (n=677). Additionally, this sample size was calculated considering 50% of the perception of an ideal safety culture, 5% of confidence limits and drawing effect of 1 (random sampling). A further 10% of participants were added to this sample size, reaching a total of 271 people. Two lists were prepared: the first contained 271 employees and the second, the same amount of replacements.

Statistical analysisThe frequency for categorical and mean variables, and standard deviation (SD) for the continuous, were both calculated.

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was calculated in order to assess the association between safety culture and job satisfaction, depressive symptoms, and burnout syndrome (≥0.6 strong correlation).17

The partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to determine the link between variables and to estimate dependency relationships between them.18 Therefore, the validation and reliability of measurements and analysis of the structural model were carried out.

In order to perform the first step, the patient safety culture construct was created in accordance with the results, which were obtained via SAQ, the job satisfaction construct referring to JSS, the depressive symptoms construct referring to PHQ-9, and the burnout construct referring to MBI.

The convergent validity was verified, considering values of average variance extracted (AVE) and it is recommended for those values to be>0.5. For the discriminant validity, a comparison criterion was adopted, in which square roots of the AVE needed to be higher than the value of the correlation between the constructs. Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α) and the composite reliability (CR) have been highlighted for a reliability evaluation, which showed acceptable values>0.6. The factorial loads of the instruments’ domains were also described, which were acceptable if ≥0.5.18

For the second step, Pearson's determination coefficient (R2) was analyzed and classified as having a large effect if R2≥26%. The predictive relevance (Q2) was examined through a coefficient of redundancy and was considered adequate when Q2>0. The community coefficient determined the effect size (f2), which was considered large if f2≥0.35. The goodness-of-fit index (GoF) was considered acceptable when >0.36.18

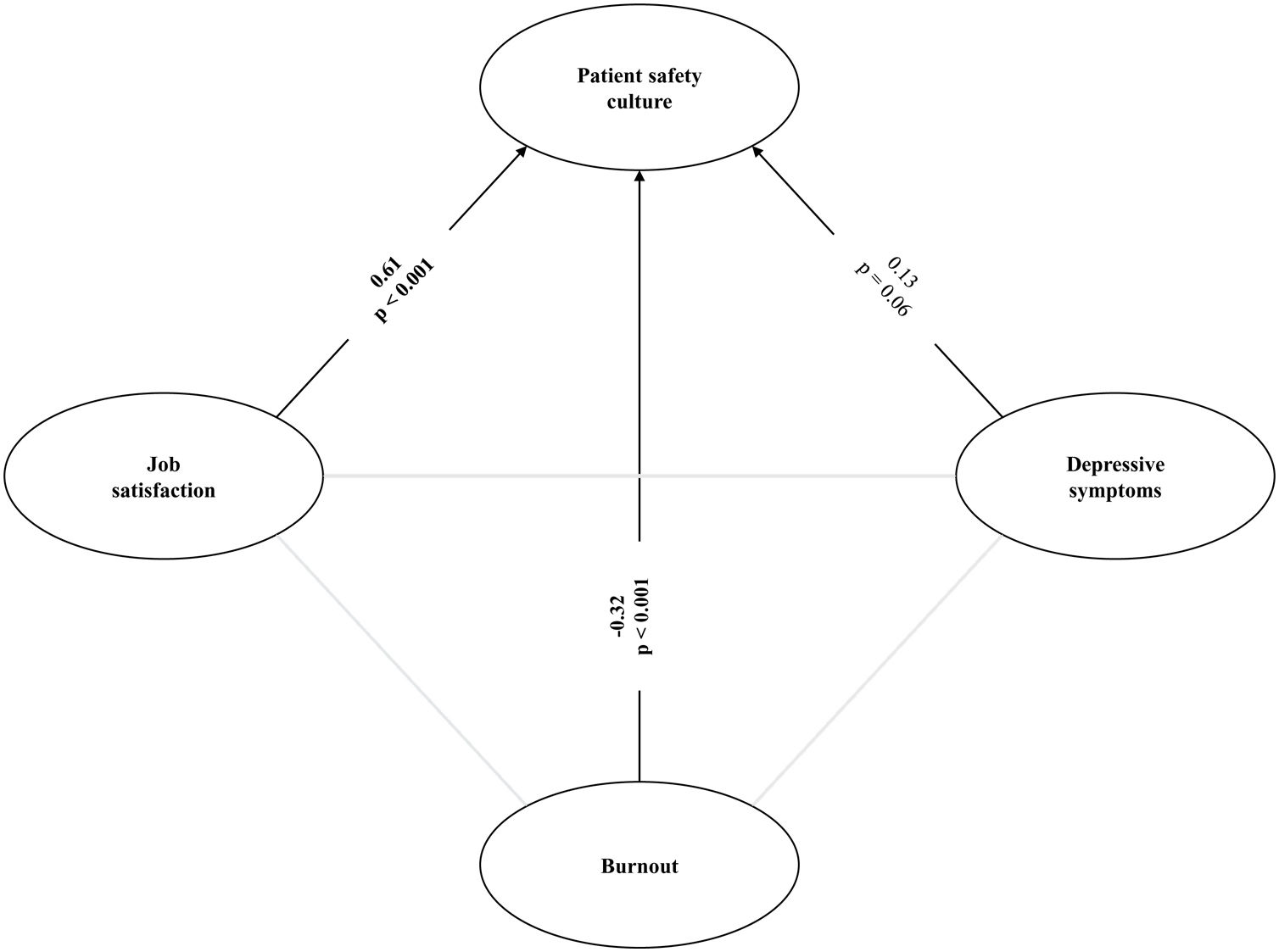

Finally, the significance and the relationship between the constructs and the path-coefficient was established, which is expressed with values between −1 and 1. Values close to 1 (or −1 for negative associations) indicate strong relationships.18

The path diagram was used in order to illustrate the relationship between the constructs. Causal relationships are represented by straight arrows, which point from the predictive variable (or construct) to the dependent variable. The curved arrows correspond to the correlations between constructs, but no causality is implied.18

The statistical program Stata (version 13.1) was used for all analyses. Additionally, the confidence interval was standardized at 95% (95% CI) as well as the significance level at 5%.

Ethical aspectsThe study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the State University of São Paulo, Brazil (Protocol no. 1.644.886, CAAE 56455316.0.0000.5426). All participants provided a written informed consent form and authorization was obtained from the institution studied.

ResultsCharacteristics of sampleA total of 271 professionals were included in the study (response rate=89%; Fig. 1).

Most of the participants were women (n=213; 79%), between 36 and 50 years of age (n=114; 42%), who belonged to the nursing team (n=125; 46%) and had 5–10 years of experience in the area (n=74; 27%; Table 1).

Sociodemographic and labor characteristics of study professionals, n=271.

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 58 | 21 |

| Female | 213 | 79 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–35 | 105 | 39 |

| 36–50 | 114 | 42 |

| ≥51 | 52 | 19 |

| Socioeconomic classa | ||

| A | 46 | 17 |

| B | 134 | 49 |

| C | 82 | 30 |

| D/E | 9 | 3 |

| Level of education | ||

| Higher education | 97 | 36 |

| Complete secondary education | 138 | 51 |

| Incomplete secondary education | 36 | 13 |

| Profession or field of activity | ||

| Physician | 24 | 9 |

| Nursing teamb | 125 | 46 |

| Other health professionalsc | 29 | 11 |

| Technical and administrative supportd | 93 | 34 |

| Interaction or direct contact with the patient | 205 | 76 |

| Time working in the area (years) | ||

| <1 | 9 | 3 |

| 1–2 | 29 | 11 |

| 3–4 | 50 | 18 |

| 5–10 | 74 | 27 |

| 11–20 | 48 | 18 |

| ≥21 | 61 | 22 |

The analysis of the total score of the instruments revealed an irregular agreement between the professionals and the institution's attitudes regarding patient safety, which was a below-ideal indicator (average SAQ=68.2; 95% CI: 66–70%; α=0.91).

The satisfaction mean was 131.2 (95% CI: 128.1–134.3; α=0.88), consequently indicating that the professionals were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with their work. In the assessment of depression, 60 professionals scored ≥9 on the PHQ-9 and reported relevant episodes of depressive symptoms (prevalence=22.1%; 95% CI: 17.2–27.1; α=0.8). Burnout syndrome was identified in 40 participants (prevalence=14.8%; 95% CI: 10.5–19; α=0.9)

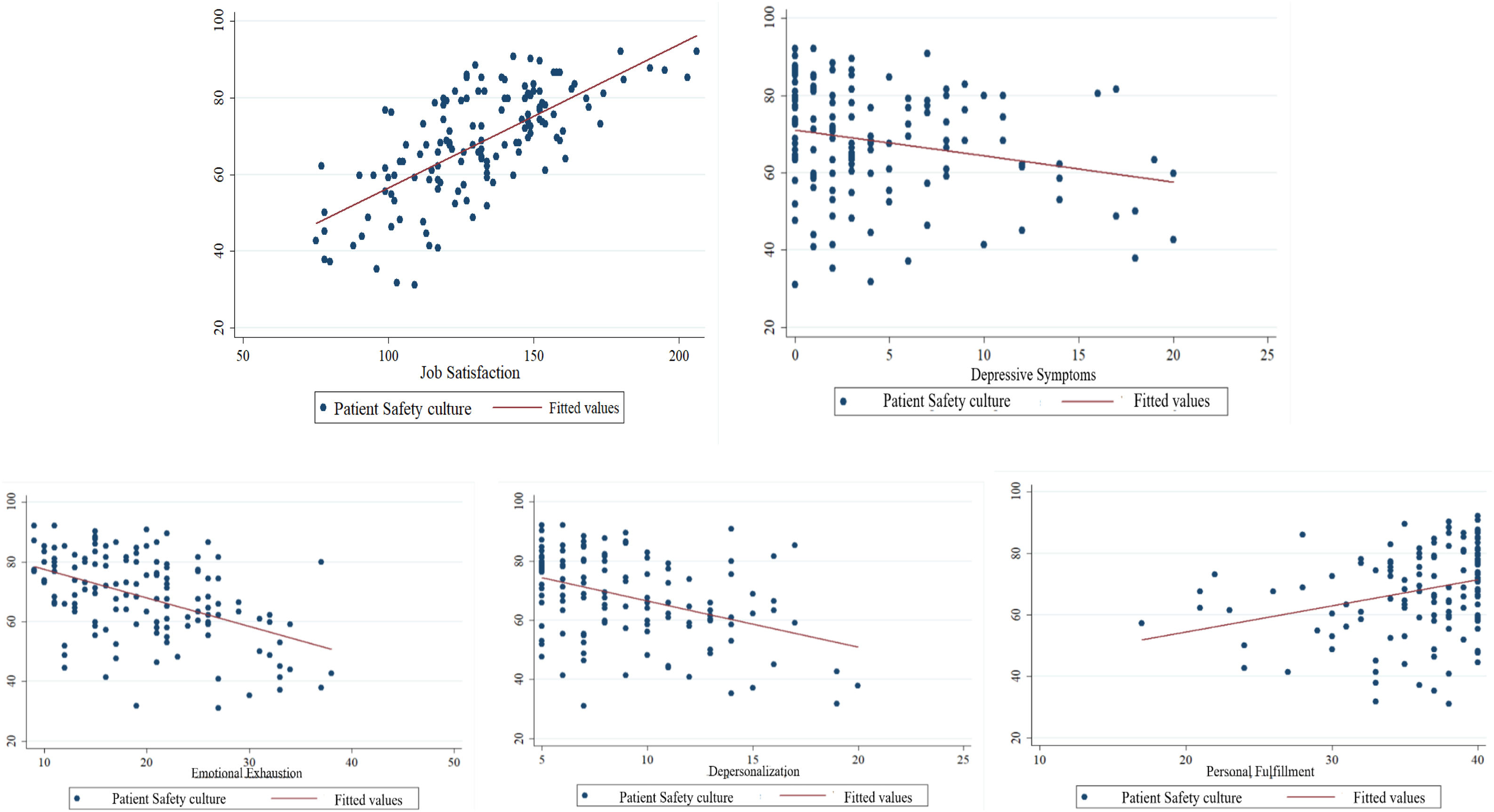

Perception of patient safety cultureIn Fig. 2 (analysis with the Pearson correlation coefficient) it is observed that the higher the job satisfaction, the greater the perception of patient safety culture in the hospital (r=0.69; P<0.001). The higher the depressive symptoms, the lower the perception of safety culture (r=−0.24; P<0.01). The higher the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (burnout dimensions), the lower the perception of patient safety culture (r=−0.47; P<0.001 and r=−0.4; P<0.001, respectively). The higher the personal fulfillment (burnout dimension), the greater the perception of patient safety culture in the hospital (r=0.28; P=0.001).

Related factors to perception of patient safety cultureIn the first phase of PLS-SEM (validation and reliability of measurements), the convergent validity of the construct of patient safety culture, depressive symptoms, and burnout were evidenced (VME≥0.5), as well as the reliability of the internal measure consistency (CC=0.85, α=0.77; CC=0.88, α=0.85; and CC=0.65; α=0.69, respectively). For the job satisfaction construct, AVE was slightly below stipulated (0.43), but reliability was attested (CC=0.87; α=0.83).

The square roots of the AVE of the constructs (patient safety culture=0.74; job satisfaction=0.65; depressive symptoms=0.69; and burnout=0.78) were higher than the correlation value between them and demonstrated the discriminant validity of the measurements.

The factorial loads of the instruments’ domains that constituted the constructs were satisfactory and are in Table 2.

Factorial loads of the domains that constituted the constructs patient safety culture, job satisfaction, depressive symptoms and burnout.

| Domains | Construct | Factorial loads |

|---|---|---|

| Patient safety culture | ||

| Teamwork climate | 0.69 | |

| Safety climate | 0.82 | |

| Stress recognition | −0.37 | |

| Job satisfaction | 0.79 | |

| Perception of management (hospital) | 0.77 | |

| Perception of management (unit) | 0.79 | |

| Working conditions | 0.82 | |

| Job satisfaction | ||

| Benefits | 0.70 | |

| Coworkers | 0.59 | |

| Communication | 0.76 | |

| Operating procedures | 0.45 | |

| Nature of the work | 0.59 | |

| Promotion | 0.63 | |

| Contingent rewards | 0.78 | |

| Pay | 0.74 | |

| Supervision | 0.57 | |

| Depressive symptoms | ||

| Little interest or pleasure in doing things | 0.71 | |

| Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | 0.8 | |

| Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 0.64 | |

| Feeling tired or having little energy | 0.8 | |

| Poor appetite or overeating | 0.64 | |

| Feeling bad about yourself | 0.74 | |

| Trouble concentrating on things | 0.7 | |

| Moving or speaking slowly/Or the opposite: being fidgety | 0.56 | |

| Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself | 0.36 | |

| Burnout | ||

| Emotional exhaustion | 0.89 | |

| Depersonalization | 0.8 | |

| Personal fulfillment | −0.66 | |

In the second step of PLS-SEM (analysis of structural model), the values of Pearson's coefficient of determination were considered to have a great effect on the correlation of the patient safety culture construct with the constructs of job satisfaction and burnout (R2=0.58 and R2=0.42, respectively). Furthermore, the results found for the predictive relevance (Q2), the community coefficient (f2) and the goodness-of-fit (GoF) were adequate and expressive among these constructs. In the correlation of the patient safety culture construct with the depressive symptoms construct, the values of these analyzes had lesser effect and were not adequate (Table 3).

Pearson's coefficient of determination (R2), predictive relevance (Q2), community coefficient (f2) and the goodness-of-fit (GoF).

| Constructs | R2 | Q2 | f2 | GoF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction→Patient safety culture | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.53 |

| Depressive symptoms→Patient safety culture | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.5 | 0.26 |

| Burnout→Patient safety culture | 0.42 | 0.23 | 0.56 | 0.49 |

The graphical representation of the complete set of this association, illustrated by the path diagram in Fig. 3, determined a causal relationship in which the constructs of job satisfaction and burnout are predictors and patient safety culture is the dependent. The association of depressive symptoms and safety culture constructs was not significant.

DiscussionIn the hospital studied, fragilities were identified in relation to patient safety culture, the professionals were not fully satisfied with their work, relevant episodes of depressive symptoms were reported and burnout was identified in about 15% of the team. In addition, this study confirms the relationship between these variables, since a higher work satisfaction results in a higher perception of safety culture. Depressive symptoms and burnout dimensions showed an inverse relationship with the safety culture.

PLS-SEM enabled us to understand the behavior of this association and establish a causal relationship. Thus, satisfaction at work and the absence of burnout proved to be predictive factors for the implementation of an ideal patient safety culture.

Our study meets the global priorities for patient safety research, which are proposed by the Global Patient Safety Alliance from the World Health Organization (WHO).19 Also, this research supports WHO's line of research on human factors, organizational aspects and individual particularities that affect work performance and safety in general.20

High participation rate was achieved in the current research, as evidenced by the high overall response rate to the instruments (89%). The method of data collection adopted, including the instruments in the electronic device and the presence of the researcher to clarify any doubts, intended to provide convenience and autonomy for the participants. In other surveys that used the same instruments, the percentage of participation ranged from 50% to 81%.21,22

In this study, the estimated reliability of the measurement with the chosen instruments was verified. This result is similar to those of the original instruments (SAQ α=0.8; JSS α=0.91; PHQ-9 α=0.9; MBI α=0.7–0.9)12–15 which confirms the efficiency of psychometric tools.

Concerning the association of variables related to psychosocial factors and patient safety, there are many studies with an approach limited to a single professional area4,23–25 as well as some studies that depict important limitations.26,27 Studies performed in other countries will be discussed further in order to analyze their relationship with our findings.

A cross-sectional study in a public hospital, with a sample majority of nursing professionals (76%), presented a correlation between job satisfaction and perception of safety (r=0.67), assessed via instruments. However, this study has limitations of selection bias, low response rate and reduced sample size (n=75).26

A research conducted with nurses (n=61,168) in 12 European countries (England, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland) and in the USA showed that hospital environments considered as good quality, i.e., in which the staff had administrative support, good social relationships and contribution to decision making, were significantly related to a lower probability of bad reports regarding patient safety (Europe, OR: 0.50 [95% CI: 0.44–0.56]; USA, OR: 0.55 [95% CI: 0.50–0.61]). Moreover, these factors were associated with better ratings by patients regarding quality of care (Europe, OR: 1.16 [95% CI: 1.03–1.32]; USA, OR: 1.18 [95% CI: 1.13–1.23]).23

In order to know the predictive factors reported by nurses (n=731) that contribute to the quality of health care provision, a study concluded through multivariate regression models that job satisfaction was an important factor (OR: 1.56 [95% CI: 1.33–1.84]). Likewise, this increase in satisfaction was also associated with higher ratings of patient safety (P<0.05).24

In Ghana, staff motivation levels of 324 employees (divided into clinical and non-clinical) in 64 primary health care establishments presented positive correlation with the efforts applied to improve patient safety (P<0.05).27

In Spain, a secondary analysis that compared the results of two previous studies, which were conducted in 24 hospitals with nursing professionals observed the relationship between the perception of safety in health care and job satisfaction.25

A systematic review on the association between the welfare of the health care team and patient safety analyzed 27 studies conducted in 16 different countries and concluded that, in most of the studies, the impaired welfare of professionals is related to outcomes of uncertainty, such as assistance failures. This review also suggests benefits for the patient, resulting from the promotion of better working environments.7

In addition, in another part of our study that has already been published,16 where we aimed to analyze the association between job satisfaction, burnout syndrome and depressive symptoms among hospital professionals, we suggest that the absence of burnout was identified as a predictive factor for the job satisfaction and depressive symptoms as a predictor for the development of burnout.

The evidences described above foster the recognition of the psychosocial work environment as a factor that intervenes in health care, as suggested by the findings of our study.

Limitations and strength of the studyDue to the cross-sectional method used, it is not possible to detect incidences, since it does not perform a follow-up period. Therefore, the exposure and outcome evaluations occur in a single moment, which hinders the establishment of a temporal relationship between them. In spite of this, this method is useful for measuring prevalence and planning health policies. Our results refer to a unique and local analysis. Furthermore, although our survey responses may vary according to individual criteria, it represents the real perception and understanding of professionals and this cannot be guaranteed with an external analysis, for example. We also recognize that, despite the validated instruments that were used in our study, it is difficult to determine that our results refer in isolation to the psychosocial factors that we measured and are not influenced by other aspects of the organizational environment. The time elapsed between the application of instruments and the date of publication of our research is one more limitation of our study.

However, a notable feat of this study that differs it from previous ones is that it presents detail and focus on different areas and professional categories present in a hospital, thus encompassing a multidisciplinary team. This is due to the understanding that the cooperation of these workers contribute directly or indirectly to health care provision. The findings of this research could raise the attention of managers to alarming problems present in the institutions, which block the development of public health improvements. In addition, this study reinforces issues that are still poorly disseminated in Brazil, such as patient safety culture and worker health.

Moreover, we recommend the development of new studies that assess other aspects that may intervene in safety culture, such as personal and organizational issues. Studies on the resulting outcomes in health care and quality of life of the professionals involved are equally important, in order to avoid an epidemic of work-related illnesses and, consequently, of adverse events for patients.

In conclusion, our study suggests that the perception of the patient safety culture is associated with job satisfaction and the burnout syndrome in hospital professionals. PLS-SEM identified job satisfaction and the absence of burnout as predictive factors for promoting an ideal safety culture.

These findings suggest that the psychosocial work environment influences the quality and safety of health care. These are important notions for policy makers and raise relevant hypotheses for future studies. It is suggested that investments aimed at improving job satisfaction and reducing professional burnout can prevent an epidemic of adverse events in patients.

FundingThis work was supported by National Council for Scientific and Technological Development of Brazil [process number: 130828/2016-5].

Conflict of interestWe declare no competing interests.

We thank the hospital workers, participants of the research, who voluntarily consented and contributed to the conception of this scientific research.

To the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development of Brazil, for the grant given to Alan Maicon de Oliveira [process number: 130828/2016-5]. The financing agency played no role in the design of the study, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or text writing. The authors are responsible for the opinions, assumptions and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article.