Positive attitude of nurses toward patient safety can play a major role in increasing the quality of nursing care and reducing missed nursing care. This study was conducted to determine the relationship between the Attitude of Nurses Toward Patient Safety and missed nursing care.

MethodsThis study was conducted in 2021 at the hospitals of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Iran). In the present study, 351 nurses were included in the study by using a stratified random sampling method. Data collection tools were demographic questionnaire, missed nursing care questionnaire, and patient safety attitudes questionnaire. Missed Nursing Care Questionnaire includes 24 items, such as patient movement, rotation, evaluation, training, discharge planning, medication prescription, scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from score 1 (I miss rarely), score 2 (I miss occasionally), score 3 (I miss usually), and score 4 (I miss always). The highest score is 96 and the lowest score is 24 on this scale. A higher score indicates a higher possibility of missed care.

ResultsThe mean total (standard deviation) of missed nursing care was 32.76 (7.13) (score range: 24–96) and the mean total score of nurses’ patient safety attitudes was 53.19 (18.71) out of 100. Results of the present study showed that nurses’ patient safety attitudes are at a moderate level and have a significant inverse relationship with the incidence of missed nursing care (P<0.001).

ConclusionAccording to the results and given the relationship between patient safety attitudes and missed nursing care, it is essential to use individual and organizational interventions to increase patient safety attitudes in various dimensions in nurses and consequently to reduce missed nursing care and improve the quality of healthcare.

La actitud positiva de las enfermeras hacia la seguridad del paciente puede desempeñar un papel principal a la hora de incrementar la calidad de los cuidados enfermeros y reducir la omisión de dichos cuidados. Este estudio fue realizado para determinar la relación entre la actitud de las enfermeras hacia la seguridad del paciente y la omisión de cuidados enfermeros.

MétodosEste estudio se llevó a cabo en 2021 en los hospitales de la Universidad de Ciencias Médicas de Tabriz (Irán). En dicho estudio se incluyeron 351 enfermeras, utilizando un método de muestreo aleatorio estratificado. Las herramientas de recopilación de los datos fueron: un cuestionario demográfico, un cuestionario de omisión de cuidados enfermeros y un cuestionario sobre actitudes de seguridad del paciente. El cuestionario de omisión de cuidados enfermeros incluye 24 ítems, tales como movimiento, rotación y evaluación del paciente, formación, planificación del alta, prescripción de medicación, que se puntúan sobre una escala Likert de 4 puntos que fluctúa entre la puntuación 1 (raramente me olvido), puntuación 2 (me olvido a veces), puntuación 3 (me olvido normalmente), y puntuación 4 (me olvido siempre). En esta escala la puntuación más alta es de 96 y la más baja de 24. La puntuación más alta indica una mayor posibilidad de omisión de cuidados.

ResultadosLa media total (desviación estándar) de omisiones de cuidados enfermeros fue de 32,76 (7,13) (rango de puntuación: de 24 a 96) y la media total de la puntuación de actitud de las enfermeras hacia la seguridad del paciente fue de 53,19 (18,71) sobre 100. Los resultados del presente estudio reflejan que las actitudes hacia la seguridad del paciente de las enfermeras se encuentran a un nivel moderado y tienen una relación inversa significativa con la incidencia de la omisión de cuidados enfermeros (p < 0,001).

ConclusiónCon arreglo a los resultados, y dada la relación entre las actitudes hacia la seguridad del paciente y la omisión de cuidados enfermeros, es esencial utilizar intervenciones individuales y organizativas para incrementar las actitudes hacia la seguridad del paciente en diversas dimensiones de las enfermeras y reducir por tanto la omisión de cuidados enfermeros, y mejorar la calidad de la atención sanitaria.

Nurses, as the largest group of service providers in the healthcare system, play a major role in the continuity of care, promoting and maintaining of patients’ health1 and among all the care provided in medical settings, nursing care has higher importance.2 Nursing care is a series of measures provided by nurses for physical, emotional, spiritual, social, and psychological care of patients and in light of these measures, the feeling of safety and security in patients is strengthened and the course of the disease is shortened.3 One of the goals of the Charter of Patients’ Rights is to ensure the functioning of the health system to meet the general needs of the patient, but in some cases, due to insufficient labor, short time, and high workload, nurses are able to fulfill only a few of their tasks and have to prioritize vital care of patients and some or all of the non-vital cares are missed or delayed, resulting in missed nursing care.4,5

Missed nursing care, known as the patient's unmet needs, refers to any aspect of the care that patients need, but for a number of possible clinical, emotional, or administrative reasons, they have been missed or delayed.6 Missed nursing care is a new concept in the area of health services that was first described in 2006 as a phenomenon in nursing by Kalisch et al.7 and then by the same researcher et al. in 2009. This model has structural variables such as hospital characteristics, ward characteristics, staff-related outcomes, and patient-related outcomes.8 Based on this model, factors such as human resources, financial resources, and communications can lead to failures on care.9 Based on the results of the study conducted by Kalisch et al. changing the patient's status three times a day or according to physician's prescription was the most missed nursing care, and other missed nursing cares included participating in intra-sector dialog sessions, oral care, patient examination and evaluation at each shift, blood sugar control and vital symptoms.10

In a study conducted by Winsett et al. the most missed nursing care that nurses mentioned was the time of giving medication and lack of attention to oral care and the justifiable factors for missed care were high workload, insufficient number of staff, inadequate staff, high patient admission, and lack of access to necessary medications when needed.11 Also, in the study conducted by Ball, the workload of nurses was mentioned as an effective factor in the incidence of missed nursing care.12 Care is a fundamental value in the nursing profession3 and the quality of nursing care is a major factor in ensuring patient safety because missed nursing care reduces the quality of nursing services provided and causes negative outcomes on the nurse and the organization and disrupts the recovery of patients and lack of receiving the care needed by patients.13–15 The negative outcomes of these care include decreased patient satisfaction and safety, falls, pressure ulcers, nosocomial infections, and increased length of stay, all of which threaten the patient's safety.16,17

One of the primary and most important goals in providing health services is to prevent harm to the patient and maintain his or her safety in providing health services.18 The World Health Organization defines safety in the health care setting as “reducing the possibility of unnecessary harm to a minimum acceptable level”.19 The concept of a patient's attitude toward safety indicates the sense of commitment and responsibility of staff to safety issues and reflects the level of individual beliefs about safety rules, safety instructions, procedures, and methods.20 One of the main problems of healthcare providers in improving the quality of care is the unsafe attitudes of staff, which is directly associated with the occurrence of hospital accidents and errors,21 since attitude shapes behavior and affects it. Hence, the main change in the safe behavior of people is a change in their attitude.22 Nurses play the largest role in caring for patients. Thus, their safe attitude in committing to protecting the patient's safety is crucial and can affect the safety status of patients.23 Missed nursing care is one of the important indicators of the quality of nursing care24 and the occurrence of missed nursing care around the world is inevitable and a threat the patient safety. By examining the types of missed nursing care and the use of effective solutions to reduce them, we can improve the quality and safety of nursing care.

Therefore, the present study was conducted to evaluate missed nursing care and its relationship with nurses’ patient safety attitudes at hospitals of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

MethodsResearch designThe present observational correlational study was conducted on nurses working at teaching hospitals of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences with the aim of examining missed nursing care and its relationship with nurses’ attitudes about patient safety at hospitals of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Morgan's formula was used in the present study to determine the sample size. Since the total number of nurses in 9 hospitals was 2200 people, considering the confidence level of 95%, and considering the accuracy of sampling d equal to 5%, the sample size was calculated to be 327 people and considering the 10% probability of dropout in samples, 355 people were selected. Among them, 4 were excluded from the study due to incomplete answers or systematic answers to questions, so 351 included final samples of this study.

Data collection tools- 1.

A questionnaire related to the demographic characteristics of nurses, which included: age, sex, marital status, employment history, education, and ward.

- 2.

Missed Nursing Care Questionnaire. This questionnaire was prepared by Kalisch in 2006 and its psychometric properties were examined by the same author in 20097 and translated in Iran by Khajooee et al.25 This questionnaire includes 24 items, such as patient movement, rotation, evaluation, training, discharge planning, medication prescription, etc. Each of these items is scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from score 1 (I miss rarely), score 2 (I miss occasionally), score 3 (I miss usually), and score 4 (I miss always). The highest score is 96 and the lowest score is 24 on this scale. A higher score indicates a higher possibility of missed care. It should be noted that this questionnaire does not have a sub-scale.

In the study of Khajooee et al., the translation and retranslation method was used for translation and the process of cultural adaptation of the Missed Nursing Care Questionnaire. Thus, the questionnaire was translated into English by three experts in translating English texts and returned to English by 3 experts. Then the amount of matches and non-matches were checked and the Persian version of the final questionnaire was used. The validity of this questionnaire was examined and confirmed by 10 faculty members of Kerman University of Medical Sciences (Iran) and other experts and its CVI index was estimated at 99%. Also, 30 samples were used for examining its reliability and its Cronbach's alpha coefficient was obtained at 91%.25

- 3.

Safety Attitude Questionnaire (SAQ). It was designed by Bryan Sexton. It included 30 questions and measures six dimensions, including teamwork climate (6 questions), safety climate (7 questions), job satisfaction (5 questions), stress recognition (4 questions), attitude toward the support of hospital management and patient safety unit (4 questions) and working conditions (4 questions). Questions 2 and 11 are scored inversely. In this questionnaire, a five-point Likert scale was used to obtain the opinions of the respondents, in which I completely disagree=1, disagree=2, I have no ideas=3, agree=4 and I completely agree=5. The questionnaire was interpreted in such a way that each of the six dimensions of safety attitude is calculated based on 100 points since all dimensions of this questionnaire have equal value and the total mean score of safety attitude is ranked from zero to 100. The total mean score of safety attitude from 80 to 100 means excellent, 60 to 80 means very good, 40 to 60 means moderate, 20 to 40 means inappropriate, 0 to 20 means poor. This questionnaire measures six dimensions.26 The validity and reliability of this questionnaire in Iran have been calculated and confirmed by Turani et al. in 2016 through Cronbach's alpha at 86%.27 In the study conducted by Khalilzadeh et al., the validity of this questionnaire was determined through content validity and its reliability was determined at 85% by using the test–retest method, and the internal correlation of safety dimensions with Cronbach's alpha was confirmed at 87%.22

Sampling was performed among the nurses of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences hospitals. Thus, after calculating the sample size according to the Morgan table and knowing the number of nurses working in the study hospitals, the number of samples in each center was obtained. Accordingly, the estimated number of samples was divided by the total number of nurses, and the result was multiplied by the number of nurses in each center to determine the number of samples in each center. After calculating the share of each center based on the number of nurses in different wards, 9 teaching hospitals were placed in different classes that common characteristic of them was their “job”. In the first stage, the number of samples from each class in proportion to the population of that class (hospital and ward) was selected. After allocating this ratio, in the second stage, the samples were selected from each of the classes using the random sampling method.

The method of data collection was face-to-face so that after obtaining permission from the Research Council of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and obtaining permission from the Committee of Regional Ethics in Research (IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.105), the researcher referred to relevant units and introduced himself. To determine the eligible people to enter the study, he obtained a list of nurses from the nursing offices and the officials of the relevant hospitals, and the quota sampling method was used for sampling. The researcher referred to hospitals during the days of the week (Saturday to Thursday) and three shifts in the morning, evening, and night to access all the nurses. After explaining the objectives of the study individually and obtaining the subjects’ consent, the questionnaire was submitted to eligible people. With the nurses’ request according to the workload and speed of response, the questionnaires were completed by the nurse himself or herself, and finally, they were collected by the researcher. Inclusion criteria of the study included having a bachelor's degree or higher and working in hospital wards as a nurse for at least six months and exclusion criteria included unwillingness to cooperate, staff whose job rank was a nurse but they are doing only administrative or secretarial tasks and the incomplete completion of the questionnaire questions (completion of less than 90% of the questions). To observe the ethical standards, questionnaires were distributed among the participants without mentioning their names and surnames, and the participants were assured that the information will remain confidential.

Data analysisThe collected data were analyzed in SPSS-16 software using descriptive statistics, regression test, Pearson, analysis of variance, and independent t-test, and P<0.05 was considered as a significant level.

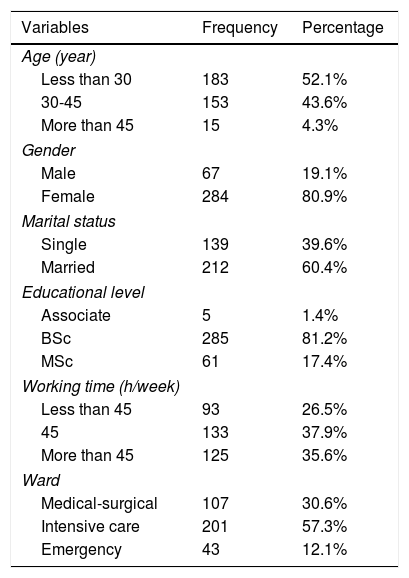

ResultsDemographic characteristicsResults of the present study in the area of demographic characteristics showed that out of 351 nurses who participated in the study, 284 (80.9%) were female and 67 (19.1%) were male. The majority of participants were married (60.4%) and had a bachelor's degree (81.2%) (Table 1).

Frequency distribution of participants according to demographic characteristics.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ||

| Less than 30 | 183 | 52.1% |

| 30-45 | 153 | 43.6% |

| More than 45 | 15 | 4.3% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 67 | 19.1% |

| Female | 284 | 80.9% |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 139 | 39.6% |

| Married | 212 | 60.4% |

| Educational level | ||

| Associate | 5 | 1.4% |

| BSc | 285 | 81.2% |

| MSc | 61 | 17.4% |

| Working time (h/week) | ||

| Less than 45 | 93 | 26.5% |

| 45 | 133 | 37.9% |

| More than 45 | 125 | 35.6% |

| Ward | ||

| Medical-surgical | 107 | 30.6% |

| Intensive care | 201 | 57.3% |

| Emergency | 43 | 12.1% |

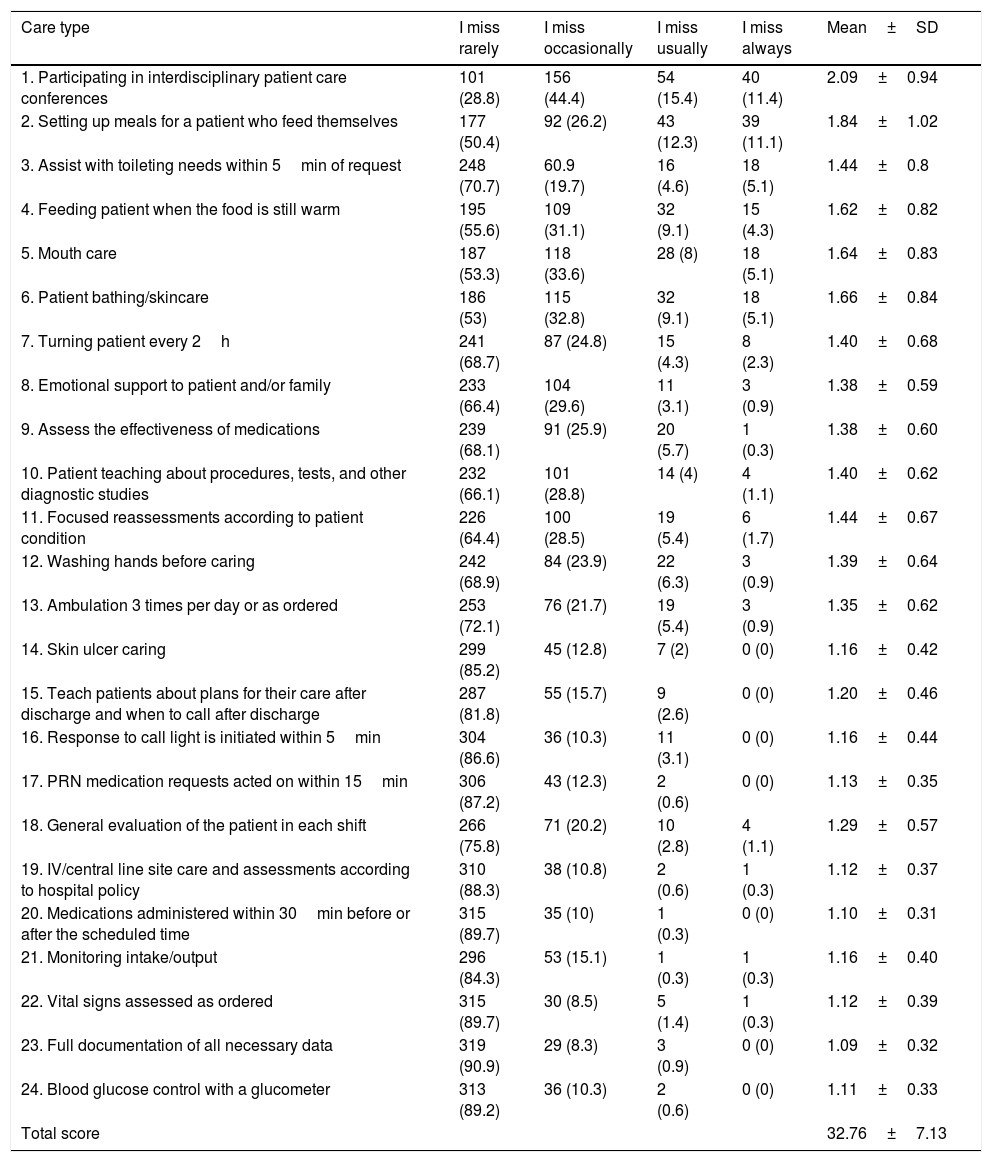

Results of missed nursing care showed that the mean total and standard deviation of missed nursing care from the nurses’ point of view was 32.76±7.13, which is low. The highest mean of missed nursing care was belonged to “Participating in interdisciplinary patient care conferences” with a mean of 2.09±0.94, “Monitoring the preparation of food for the patient who can eat himself or herself” with a mean of 1.84±1.02, “performing or monitoring patient baths and skincare” with a mean of 1.66±0.84 and “performing oral cares” with a mean of 1.64±0.83. The lowest mean score belonged to “Complete recording of essential patient information” with a mean of 1.09±0.32, “Prescription of medicine within 30min before or after the scheduled time” with a mean of 1.10±0.31, and “Blood glucose control with a glucometer” with a mean 1.11±0.33 (Table 2).

Descriptive results of missed nursing care.

| Care type | I miss rarely | I miss occasionally | I miss usually | I miss always | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Participating in interdisciplinary patient care conferences | 101 (28.8) | 156 (44.4) | 54 (15.4) | 40 (11.4) | 2.09±0.94 |

| 2. Setting up meals for a patient who feed themselves | 177 (50.4) | 92 (26.2) | 43 (12.3) | 39 (11.1) | 1.84±1.02 |

| 3. Assist with toileting needs within 5min of request | 248 (70.7) | 60.9 (19.7) | 16 (4.6) | 18 (5.1) | 1.44±0.8 |

| 4. Feeding patient when the food is still warm | 195 (55.6) | 109 (31.1) | 32 (9.1) | 15 (4.3) | 1.62±0.82 |

| 5. Mouth care | 187 (53.3) | 118 (33.6) | 28 (8) | 18 (5.1) | 1.64±0.83 |

| 6. Patient bathing/skincare | 186 (53) | 115 (32.8) | 32 (9.1) | 18 (5.1) | 1.66±0.84 |

| 7. Turning patient every 2h | 241 (68.7) | 87 (24.8) | 15 (4.3) | 8 (2.3) | 1.40±0.68 |

| 8. Emotional support to patient and/or family | 233 (66.4) | 104 (29.6) | 11 (3.1) | 3 (0.9) | 1.38±0.59 |

| 9. Assess the effectiveness of medications | 239 (68.1) | 91 (25.9) | 20 (5.7) | 1 (0.3) | 1.38±0.60 |

| 10. Patient teaching about procedures, tests, and other diagnostic studies | 232 (66.1) | 101 (28.8) | 14 (4) | 4 (1.1) | 1.40±0.62 |

| 11. Focused reassessments according to patient condition | 226 (64.4) | 100 (28.5) | 19 (5.4) | 6 (1.7) | 1.44±0.67 |

| 12. Washing hands before caring | 242 (68.9) | 84 (23.9) | 22 (6.3) | 3 (0.9) | 1.39±0.64 |

| 13. Ambulation 3 times per day or as ordered | 253 (72.1) | 76 (21.7) | 19 (5.4) | 3 (0.9) | 1.35±0.62 |

| 14. Skin ulcer caring | 299 (85.2) | 45 (12.8) | 7 (2) | 0 (0) | 1.16±0.42 |

| 15. Teach patients about plans for their care after discharge and when to call after discharge | 287 (81.8) | 55 (15.7) | 9 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1.20±0.46 |

| 16. Response to call light is initiated within 5min | 304 (86.6) | 36 (10.3) | 11 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 1.16±0.44 |

| 17. PRN medication requests acted on within 15min | 306 (87.2) | 43 (12.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1.13±0.35 |

| 18. General evaluation of the patient in each shift | 266 (75.8) | 71 (20.2) | 10 (2.8) | 4 (1.1) | 1.29±0.57 |

| 19. IV/central line site care and assessments according to hospital policy | 310 (88.3) | 38 (10.8) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 1.12±0.37 |

| 20. Medications administered within 30min before or after the scheduled time | 315 (89.7) | 35 (10) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1.10±0.31 |

| 21. Monitoring intake/output | 296 (84.3) | 53 (15.1) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1.16±0.40 |

| 22. Vital signs assessed as ordered | 315 (89.7) | 30 (8.5) | 5 (1.4) | 1 (0.3) | 1.12±0.39 |

| 23. Full documentation of all necessary data | 319 (90.9) | 29 (8.3) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1.09±0.32 |

| 24. Blood glucose control with a glucometer | 313 (89.2) | 36 (10.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1.11±0.33 |

| Total score | 32.76±7.13 |

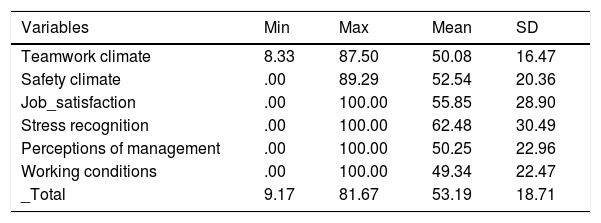

Examination of the data related to the Patient Safety Attitude Questionnaire showed that the mean total score was 53.19±18.71 (out of 100). To compare the means of each dimension with each other, scores were calculated from the same ceiling (number 100). The results of Table 3 show that among the different dimensions of nurses’ safety attitudes, the dimension of stress recognition with a mean of 62.48 is the highest score and the dimension of working conditions with a mean of 49.34 had the lowest score (Table 3).

Descriptive results of different dimensions of safety attitude.

| Variables | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teamwork climate | 8.33 | 87.50 | 50.08 | 16.47 |

| Safety climate | .00 | 89.29 | 52.54 | 20.36 |

| Job_satisfaction | .00 | 100.00 | 55.85 | 28.90 |

| Stress recognition | .00 | 100.00 | 62.48 | 30.49 |

| Perceptions of management | .00 | 100.00 | 50.25 | 22.96 |

| Working conditions | .00 | 100.00 | 49.34 | 22.47 |

| _Total | 9.17 | 81.67 | 53.19 | 18.71 |

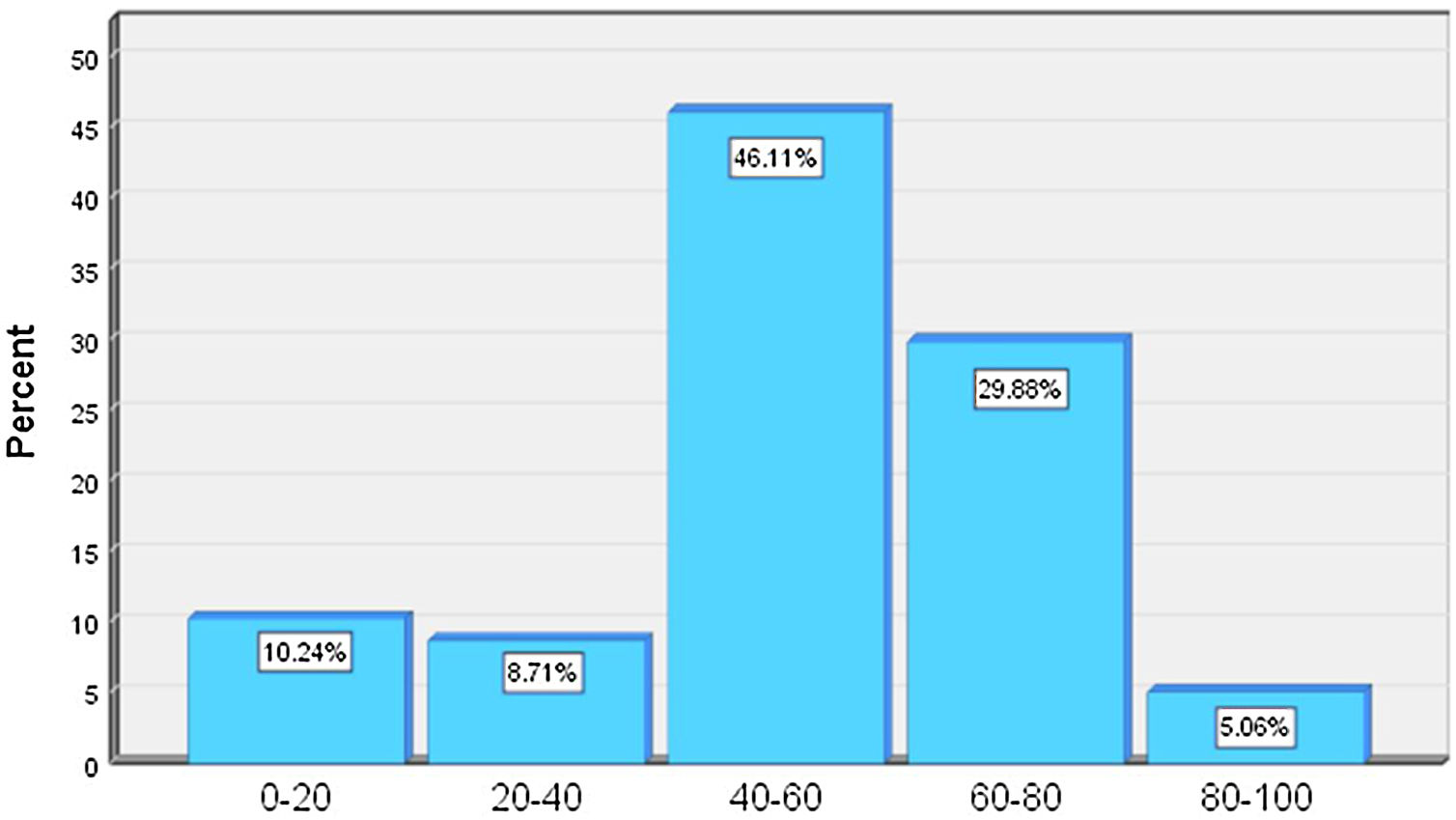

The following figure reports the total score of safety attitude based on the ranking of poor (0–20), relatively poor (20–40), moderate (40–60), good (60–80), and excellent (80–100). According to this figure, nurses’ safety attitudes are moderate in 46.11% of cases (Fig. 1).

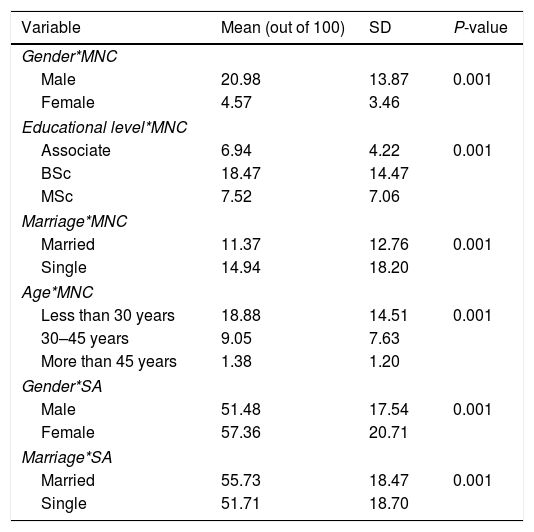

Examining the mean scores of missed nursing care at the levels of qualitative demographic variables of the study were performed using independent t-test and one-way analysis of variance. Based on the results, the mean scores of missed nursing care in the levels of age, gender, marriage, and education level show a statistically significant difference (Table 4).

Investigating the relationship between missed nursing care (MNC) and safety attitude (SA) with nurses’ demographic variables.

| Variable | Mean (out of 100) | SD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender*MNC | |||

| Male | 20.98 | 13.87 | 0.001 |

| Female | 4.57 | 3.46 | |

| Educational level*MNC | |||

| Associate | 6.94 | 4.22 | 0.001 |

| BSc | 18.47 | 14.47 | |

| MSc | 7.52 | 7.06 | |

| Marriage*MNC | |||

| Married | 11.37 | 12.76 | 0.001 |

| Single | 14.94 | 18.20 | |

| Age*MNC | |||

| Less than 30 years | 18.88 | 14.51 | 0.001 |

| 30–45 years | 9.05 | 7.63 | |

| More than 45 years | 1.38 | 1.20 | |

| Gender*SA | |||

| Male | 51.48 | 17.54 | 0.001 |

| Female | 57.36 | 20.71 | |

| Marriage*SA | |||

| Married | 55.73 | 18.47 | 0.001 |

| Single | 51.71 | 18.70 | |

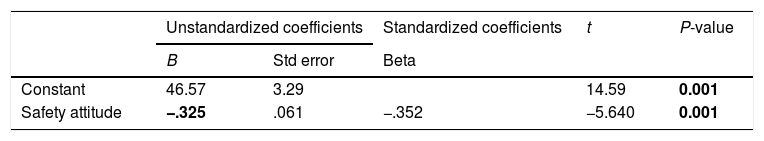

The results of the study also showed a statistically significant relationship between nurses’ patient safety attitudes and some demographic variables (P<0.05). The mean scores of nurses’ patient safety attitudes were significantly different at the levels of gender and marriage. Due to the multiplicity of variables, only significant items are shown in Table 4. Before investigating the relationship between nurses’ patient safety attitudes and missed nursing care, the normality of the dependent variable (missed nursing care) was assessed using the Smirnov–Kolmogorov test and the normality of this variable was confirmed based on P-value (P=0.25). Based on Table 5, the results of regression analysis show that the effect of positive attitude of nurses toward patient safety in reducing missed nursing care is significant (P<0.0001), so that with a 1% increase in the score of patient safety attitude in nurses, the level of missed nursing care decreases by 0.325%.

DiscussionThis predictive study was conducted to determine the relationship between missed nursing care and Attitude of Nurses toward the Patient Safety in Educational Medical Centers of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. The present study's findings showed that the total score of missed nursing care was lower than the average. inconsistent with the findings of the present study, Yaghoubi et al. conducted a study in a military hospital in Tehran, where they concluded that the missed nursing care was moderate.28 However, the findings of another study by Zúñiga et al. in Switzerland in 2015 showed low missed nursing care.29 The differences in the results of these studies could be attributed to different settings (military hospital Vs educational hospitals). Another differences in the results of these studies may lie in different study populations. In this study, the researchers investigated missed nursing care among Nurses of all wards. While in other studies, the study was conducted mainly in high-risk and high-workload wards such as emergency ward.30

Results of evaluating missed nursing care showed that the highest mean score of missed nursing care belonged to participating in interdisciplinary classes of patient care, monitoring of food preparation for the patient who can eat himself or herself, performing or monitoring the patient's baths and skincare, respectively, which is in line with the results of the research conducted by Rezaee et al.31 Kalisch et al., Kalisch, and Lee also reported that participating in interdisciplinary patient care conferences had the highest mean score of missed nursing care.32 However, in the study conducted by Duffy et al., it was reported that most missed nursing care was displacing patients three times a day or based on physician's order, participating in interdisciplinary patient care classes, and performing oral care, respectively.33 With regard to participating in educational classes as the most missed nursing care, it can be stated that the inadequate time for the formation of classes can be one of the important reasons. At the first glance, this issue may not be very important, it should be noted that non-participation of nurses in educational classes reduces up-to-date information of nurses in the clinic and ultimately has a negative impact on the quality of nursing care.

When nurses in a caring situation do not have adequate information, they will definitely provide poor quality care. Thus, to prevent missed nursing care, it seems that caregivers should provide training at appropriate times and in accordance with the needs of the nurse. Continuous education, which includes non-formal education, short courses, and conferences, can provide high-quality care for patients.34 Regarding the preparation of foods for patients who eat themselves, due to the presence of companions in the general wards of the hospital, nurses expect the patient to perform basic care such as feeding the patient and skin and mouth care of the patient. Thus, nurses do not consider such basic nursing practices as a part of their nursing duties, so they do not pay enough attention to these cares.

Based on the results of the present study, the lowest mean scores of missed nursing care belonged to the item of the complete recording of necessary patient information, prescription of medications within a maximum period of 30min before or after the scheduled time, and blood glucose control with a glucometer. Regarding the complete recording of essential information of the patient and car glycemic control, these results are in line with those of studies conducted by Khajooee et al. and John et al.4,25 Smith et al. and Kim et al. also reported blood sugar control care as the least missed nursing care.13,35 In the analysis of these results, it can be stated that due to the existence of an accurate documentation system of patient vital information and the attention paid in this area and its significant effect on the accreditation of hospitals, the low level of missed care of the complete recording of patient vital information is an expected result. Also, since the most important need of patients is the timely prescription of medications, the reason that prescribing medications and controlling blood sugar is the least missed nursing care is probably due to the existence of an accurate system of recording these cases in the medical records and special papers, helping staff in reminding them in doing these cares.

Also, the results of the present study showed that missed nursing care was more in male nurses than female nurses, but with increasing employment experience and with increasing age of clinical staff, this care has decreased. Both of these results are in line with those of research conducted by Vatankhah et al.36 However, the age variable is not consistent with the result of a study conducted by Castner et al. since their results showed that increasing employment history leads to an increase in the rate of missed nursing care.36 In the analysis of these results, it seems that the financial concerns of male nurses, who are primarily responsible for providing for living expenses, and the fatigue of long work shifts can be involved in increasing missed nursing care. Also, many missed nursing care is related to lack of experience, and nurses are able to do nursing care after attending clinical wards and nursing care is not missed. In fact, experience is an essential component of care.

Regarding the status of nurses’ patient safety attitudes, nurses’ safety attitudes are moderate in most cases. This result is consistent with the results of studies conducted by Khalilzadeh et al.,22 Arab et al.,37 in which most participants showed a moderate level of patient safety attitudes, indicating that healthcare providers are not sufficiently aware of patient safety and there is a need to improve patient safety attitudes and perceptions among nurses. Based on studies conducted by Alzahrani et al., Al Mugheed et al., and Tunçer Ünver et al., the majority of participants’ attitudes toward patient safety were lower.38–40 However, in the study conducted by Arab et al.,37 half of the healthcare providers were at a very good and excellent status and half of them were at moderate to poor status in terms of patient safety.

Regarding the dimensions of safety, results of the present study showed that among the different dimensions of nurses’ safety attitudes, the stress recognition dimension had the highest score, and the working conditions dimension had the lowest score among nurses, which is in line with the results of the study conducted by Arabi et al.21 Also, in terms of the high score of stress recognition dimension, this result is in line with that of the study conducted by Etemadinezhad et al.,41 Tourani et al.,27 and in terms of the low score of working conditions dimension, it is consistent with the results of the study conducted by Chaboyer et al.42 However, the study conducted by Ünver et al. stress recognition obtained the lowest score, which is inconsistent with the results of our study.43 This difference in results might be due to differences in the working conditions of nurses, including the type of hospitals, the number of service provider personnel, number of patients, type of work shift, employment history, the large volume of work, and so on.

Considering the effect of demographic factors on patient safety attitude, based on the results of the study, there was no significant relationship between the total score of patient safety attitude and age, type of ward, working hours, education level, but there was a significant relationship between gender and marital status and level of patient's safety attitude so that females and married people had a higher safety attitude than single and male subjects. In this regard, Niknejad et al.21 reported that the mean score of safety attitude of married caregivers was significantly higher than that of single caregivers, but the safety attitude was higher in males than females. In the study conducted by Zhao et al. and Kristensen et al., consistent with our study results, females scored higher than males in safety attitudes.44,45 The high level of safety attitudes in females compared to males may be due to the greater accuracy and concentration of females in doing duties and tasks than males.

The results also revealed that the positive attitude of nurses toward patient safety is effective in reducing missed nursing care. Wake et al. conducted a study to evaluate nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding patient safety in 2021. The results of the mentioned study revealed that nurses who had positive patient safety attitudes had better practice than nurses with a negative attitude.46 Also, Hong et al. conducted a study to investigate the relationship between the level of safety attitude and safe practice of nurses in the emergency departments of South Korean hospitals in 2015. The study also revealed a positive relationship between the level of safety attitude of nurses and safe practice.47 Thus, it can be stated that improving nurses’ perception and patient safety attitudes improve the quality of nursing care and reduce the rate of missed nursing care. Haynes et al. also reported that the positive attitude of healthcare providers toward safety improves the safety status of patients after surgery and reduces complications and mortality rates.48 The results of the present study also support those of previous studies and indicate that missed nursing care is a common problem in medical centers, and there is little information about the extent of this problem and its related factors, so more studies are needed in this area. Thus, enhancing the awareness of managers and staff on missed nursing care and finding its root can improve staff attitudes toward patient safety and reduce the incidence of unsafe behaviors and missed nursing services.

The main limitation of this study was using a questionnaire, which has a self-report aspect, to collect the data. Thus, the answers might be affected by incorrect answers and staffs’ lack of confidence in the implementation of research project results, leading to reduced commitment to provide honest answers to the questionnaire questions. The researcher tried to convince them to participate in the study by discussing and explaining the importance of the results for the education and training of nurses.

ConclusionBased on the results, the rate of missed nursing among the nurses was evaluated at a low level and their patient safety attitude was evaluated at a moderate level. With increasing patient safety attitudes in nurses, the rate of missed nursing care decreases. Based on these results, it is essential to use individual and organizational interventions to increase patient safety attitudes in various dimensions in nurses and consequently reduce missed nursing care to improve the quality of nursing care.

Authors’ contributionOmid Zadi Akhuleh and Zahra Sheikhalipour did overall supervision, material provision, study conception. Parvin Rahmani and Fatemeh Molaei Tavani did data accumulation. Mohammad Taghi Khodayari did statistical analysis, data provision. Omid Zadi Akhuleh and Parvin Rahmani did data provision, manuscript preparation. Zahra Sheikhalipour and Mozhgan behshid did manuscript preparation, final edit, study conception.

FundingThis research was supported by student research committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Grant numbers:1400-02-06-67208).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and assistance provided by all participants.